Summary

The role of cytosine methylation in the structure and function of enhancers is not well understood. In this study, we investigate the role of DNA methylation at enhancers by comparing the epigenomes of the HCT116 cell line and its highly demethylated derivative, DKO1. Unlike promoters, a portion of regular and “super-” or “stretch” enhancers show active H3K27ac marks co-existing with extensive DNA methylation, demonstrating the unexpected presence of “bivalent chromatin” in both cultured and uncultured cells. Furthermore, our findings also show that bivalent regions have fewer nucleosome-depleted regions and transcription factor binding sites than monovalent regions. Reduction of DNA methylation genetically or pharmacologically leads to a decrease of the H3K27ac mark. Thus DNA methylation plays an unexpected dual role at enhancer regions, being anti-correlated focally at transcription factor binding sites but positively correlated globally with the active H3K27ac mark to ensure structural enhancer integrity.

eTOC Blurb

The epigenetic landscape of enhancers has an unexpected characteristic; both regular and super-enhancers can be bivalent in their chromatin structures, carrying active H3K27ac and repressive DNA methylation marks on the same nucleosomes. Unlike monovalent enhancers, these bivalent regions are stabilized by and may require DNA methylation to potentially remain active.

Introduction

The accessibility and function of chromatin features is governed by the presence of covalent marks on the histones and DNA, which constitute individual nucleosomes. In general, these nucleosomes have either “active” or “inactive” marks in a mutually exclusive manner (Cao and Zhang, 2004; Kimura et al., 2004; Koyanagi et al., 2005). The co-occurrence of potentially conflicting signals was originally termed as “bivalency” to describe the co-existence of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 on individual nucleosomes (Bernstein et al., 2006). Bivalency with respect to other histone marks was also very recently described for H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 modifications (Matsumura et al., 2015), suggesting that histone modification bivalency originally might be more common than previously realized but has not been investigated with respect to the generally repressive DNA methylation mark.

We focused our attention on enhancers whose functions are key to the spatial and temporal control of gene expression. They are located in or between genes and are bound by transcription factors to regulate expression of target genes in cis or in trans through chromatin looping to gene promoters (Bulger and Groudine, 2011). The accepted chromatin signature for active enhancers is the presence of both the H3K4me1 and the H3K27ac marks (Rada-Iglesias et al., 2011). Over 70% of H3K27ac-marked enhancers are active and positively affect transcription in vivo (Nord et al., 2013), indicating that H3K27ac at enhancers while common is not always indicative of actively engaged enhancers (Lin et al., 2016). Enhancer activity can also be characterized by specific transcription factor (TF) and co-factor binding such as EP300 (Heintzman et al., 2007) and by RNAPII-mediated enhancer transcription of short bidirectional, unspliced RNAs (Andersson et al., 2014).

In cancer, gene promoters and enhancers can be aberrantly DNA methylated (Aran and Hellman, 2013) but the exact role of DNA methylation at enhancers still needs to be elucidated. The general assumption is that loss of DNA methylation at enhancers leads to upregulation of the expression levels of the respective gene(s), while DNA hypermethylation has the opposite effect. This more traditional view of DNA methylation is comparable to its role at gene promoters; however, based on more recent findings, it might play a more dynamic role at enhancers (Calo and Wysocka, 2013).

Unmethylated DNA with high CpG density at enhancers might keep chromatin accessible (Wiench et al., 2011); in contrast, regions with low CpG density might be rendered accessible upon factor binding and they may not be suppressed by DNA methylation (Stadler et al., 2011; Wiench et al., 2011). Also, enhancers that are active during development but inactive in adults, where they do not carry active histone marks or methylation (Hon et al., 2013), indicate that hypomethylation is not sufficient for enhancer activation and the question rises whether it is required at all for activation (Hon et al., 2013). It was also shown that lowly methylated and CpG-poor regions (LMRs of ~30% methylation) can have enhancer characteristics such as active histone marks, DNase hypersensitivity and increased target gene expression. The insulator protein CTCF can bind to these enhancers, indicating that other proteins might be able to bind methylated regions (Stadler et al., 2011). DNA methylation dynamics at LMRs can also be actively processed; DNA hydroxymethylation and the catalytic TET proteins are present at these sites (Serandour et al., 2012; Stadler et al., 2011) and at enhancers in mouse embryonic stem cells where its loss leads to reduction of DNA hydroxymethylation, followed by a gain of DNA methylation and reduced enhancer activity (Hon et al., 2014). Recently, we showed that hypomethylation is accompanied by the formation of nucleosome-depleted regions (NDRs), while enhancer silencing is associated with gain of nucleosomes and DNA hypermethylation (Lay et al., 2015; Taberlay et al., 2011; Taberlay et al., 2014).

Recent studies have focused on a class of large enhancers, termed “stretch or super-enhancers”. The latter consist of clusters of smaller enhancers and are distinguished from regular enhancers by their size, TF content and density as well as their increased activation of target genes (Parker et al., 2013; Spitz and Furlong, 2012; Whyte et al., 2013).

The relationship between the active enhancer mark H3K27ac and cytosine methylation has only been studied to some extent and it is still not clear whether DNA methylation plays an active role in shaping enhancers by evicting TFs or passively covers TF binding sites after eviction (Calo and Wysocka, 2013). Here we investigated the role of DNA methylation in regular and super-enhancers, by comparing them to gene promoters. We use the highly methylated colon cancer cell line HCT116 and its derivative DKO1 cell line, which has been genetically modified to lose about 95% of its parental DNA methylation level (Egger et al., 2006; Rhee et al., 2002) and we pharmacologically remove DNA methylation in HCT116 cells to define its relationship.

Results

H3K27ac and DNA methylation at enhancers

Our nucleosome occupancy and methylome sequencing (NOMe-seq) technique allows us to assess the methylation levels of almost every CpG site in the entire genome (Kelly et al., 2012; Kelly et al., 2010). We coupled this assay with H3K27ac ChIP-seq data for three cancer cell lines and their normal counterparts. H3K27ac peaks were called over the entire genome of the investigated cells and classified into three mutually exclusive genomic regions: promoters (transcriptional start sites +−1500bp), regular and super-enhancers. The latter category contains regular enhancers or enhancer constituents that belong to a super-enhancer region, that were previously identified by the Young laboratory (Heinz et al., 2010; Hnisz et al., 2013) or by the HOMER super-enhancer calling algorithm (Heinz et al., 2010). In average, the three categories of H3K27ac peaks did not differ much in size (Fig. S1A). We decided to continue our enhancer study using the active H3K27ac mark alone and we are aware that not all of H3K27ac-marked enhancers are active and positively affect transcription in vivo (Nord et al., 2013). However, this still represents the majority of H3K27ac-marked enhancers, suggesting that while not entirely perfect, H3K27ac is still a reliable and accepted mark of enhancers (Lin et al., 2016). In addition, we also found that over 60% of H3K27ac peaks of regular and super-enhancers in HCT116 cells are overlapped by the H3K4me1 mark that is frequently found at poised or active enhancers (Fig. S1B).

We then investigated the DNA methylation status of the normal HMEC cells and the breast cancer cell line MCF7 as well as normal PREC cells and the prostate cancer cells PC3 (Fig. 1A–D). In addition, normal colon mucosa and colon cancer HCT116 cells were investigated at H3K27ac-enriched regions (Fig. 1E, F) and classified into lowly (<30%), intermediate (30–70%) and highly methylated (>70%) regions. More than 80% of promoter regions are lowly methylated in all samples, which is expected for active gene promoters carrying the H3K27ac mark; however, regular and super-enhancer regions show an unprecedented co-existence of DNA methylation with the active H3K27ac mark. In HCT116 cells, we observed that 38% of regular enhancers are highly methylated while only 28% have low methylation levels. In super-enhancers, this is even more pronounced with 64% of all super-enhancer constituents falling into the highly methylated region category compared to 6% in the lowly methylated one (Fig. 1F). In normal colon, a similar trend for regular and super-enhancer constituents can be observed, where a higher percentage of enhancers are highly methylated than lowly methylated (Fig. 1E). Thus the co-existence of DNA methylation and H3K27ac at enhancer regions is not a cancer- or culture-specific phenomenon since it is observed in all three normal cell types, although the percentage of regions carrying both marks is always higher in the cancer than the normal cells, especially in super-enhancer regions. By comparing monovalent to bivalent enhancer regions, in both cases the majority of H3K27ac peak enrichments just meet our p-value cutoff, independent of their DNA methylation level. Since our cutoff is very stringent (p=10−10), it is perhaps not surprising that most H3K27ac peaks (dark red color of scatter plot density) have an enrichment level around 6 (log2 read count). The very highly enriched peaks (>8; log2 read count) are rarer and thus fluctuate more in the extent of their H3K27ac enrichment (Fig. 1). Similarly, 42% of all H3K4me1 peaks in HCT116 cells co-exist with DNA methylation levels >70% (Fig. S1C), while 43 and 51% of bivalent regular and super-enhancer regions, respectively carry the H3K4me1 mark (Fig. S1B).

Fig. 1. H3K27ac co-exists with DNA methylation at regular and super-enhancers but not at promoters.

Smooth scatter plots of H3K27ac-enriched region quantifications (log2 of read count) against the average DNA methylation level of the CpG sites within the same regions in HMEC (A), MCF7 (B), PREC (C), PC3 (D), normal colon (E) and HCT116 cells (F). Promoters are defined by H3K27ac peaks within +-1500bp of TSSs, while regular enhancers comprise H3K27ac peaks outside the +-1500bp TSSs but not part of a super-enhancer region. Super-enhancers are defined by H3K27ac peaks or constituents that are not part of regular enhancers or TSSs. White dotted threshold lines have been drawn at 30% and 70% for DNA methylation cutoffs. The cold to warm color scale indicates a low to high density in the scatter plot. Percentages in the squares reflect the percentage of H3K27ac regions that fall between the indicated boundaries. Panels (G, H & I) show genome browser shots of regular (G&H) and super-enhancer (I) regions. The first track shows binding sites of TCF4 in purple. This is followed by a gene, CGI and H3K27ac peak tracks in HCT116 cells. Wiggle plots of H3K27ac ChIP-seq enrichment in HCT116 cells and NOMe-seq data are shown below. The first track of the NOMe-seq heatmap shows HCT116 CpG methylation from low to high (green to red), followed by accessibility from low to high (yellow to blue). Black boxes highlight regions of focal DNA demethylation with high H3K27ac enrichment, chromatin accessibility and TCF4 binding. Pink boxes highlight regions with H3K27ac enrichment and DNA methylation in HCT116 cells. Orange boxes indicate transcription start sites. See also Fig. S1.

The patterns of DNA methylation and H3K27ac were then studied in more detail at both types of enhancers in HCT116 cells (Fig. 1G–I). Regular enhancers have defined peaks of H3K27ac that can be bound by TCF4 in HCT116 cells (ENCODE), a transcription factor known to bind enhancer regions and correlate with H3K27ac (Angus-Hill et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). The chromatin in the bound region is more accessible than the surrounding chromatin (black box) (Fig. 1G & I). Other regular enhancer regions that are not bound by TCF4, show co-existence of H3K27ac and DNA methylation (pink boxes), some of which are located in CpG islands (Fig. 1H).

In super-enhancer loci (Fig. 1I), the constituent enhancer cluster consists of unmethylated regions bound by TCF4 (black boxes) alongside regions that carry both marks (pink boxes). Thus the accessible and unmethylated transcription factor binding sites (black boxes) in super-enhancers appear as well-defined foci in a large region enriched in H3K27ac and DNA methylation (pink boxes). Since the active H3K27ac mark can also be found at TSS regions of active and unmethylated promoters, we highlighted these regions with orange boxes in the given example (Wang et al., 2008) (Fig. 1I).

These findings suggest that transcription factor binding sites are unmethylated and accessible in enhancers and promoters in presence of the H3K27ac mark. These sites are surrounded by wide-spread DNA methylation in enhancers, showing a co-existence of DNA methylation and H3K27ac.

Bivalent chromatin exists at enhancers

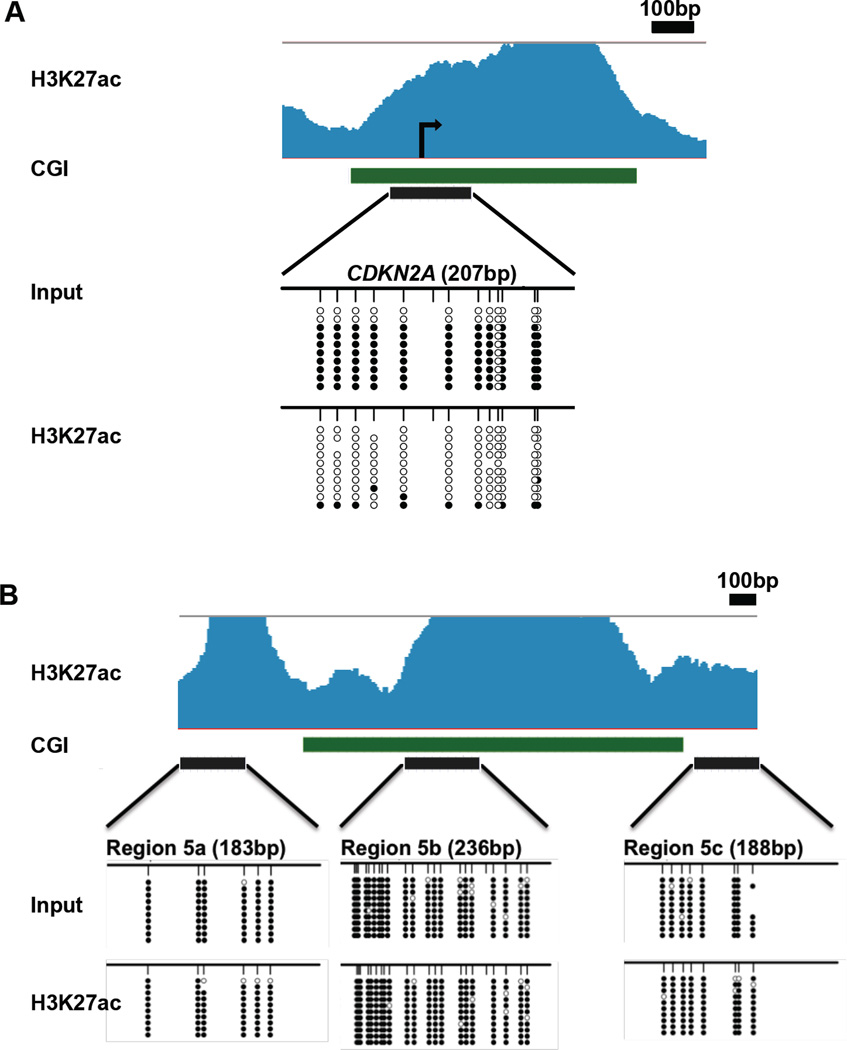

The co-existence of the H3K27ac mark with the repressive DNA methylation mark is unexpected. We thus validated our results by examining the CDKN2A promoter, which is known to have one allele methylated and the other unmethylated in HCT116 cells (Fig. 2A) (Myohanen et al., 1998). ChIP bisulfite sequencing of this locus confirmed that the H3K27ac histone modification is only present on the unmethylated allele within the CpG island, while the input shows both alleles with a bias towards the methylated one (Fig. 2A). To confirm the presence of DNA methylation at regions coexisting with H3K27ac at the same location by our genome-wide analysis (Fig. 1), we bisulfite sequenced DNA pulled-down by the H3K27ac antibody from HCT116 cells (Fig. 2B). We chose three regions close to a CpG island in a 2.4kb region within a super-enhancer to compare the data with that of the CDK2NA CpG island. All three regions were methylated in most sequenced clones (Fig. 2B). This demonstrates the presence of an active histone mark on a methylated CpG island. To further validate the findings, we bisulfite sequenced 15 additional regions identified in the genome-wide screen as having high levels of both marks in HCT116, MCF7 and PC3 cells after pull-down by the H3K27ac antibody (Fig. S2A–E). All potentially bivalent regions showed almost 100% methylation of the sequenced CpG sites (Fig. S2A–E) indicating the co-occurrence of active and inactive chromatin marks on the same nucleosome

Fig. 2. Bivalent chromatin exists at enhancers but not at promoters.

(A) Schematic representation of the CDKN2A promoter. H3K27ac enrichment in HCT116 cells is shown in light blue, followed by the CDKN2A gene track in dark blue, a CpG island in green and the region amplified by PCR in black. Input and H3K27ac ChIP DNA was bisulfite sequenced. Every row shows a different clone and every circle a CpG site. White circles indicate unmethylated sites, while black circles are methylated CpG sites. (B) Three consecutive methylated and H3K27ac-marked regions from our genome-wide data within a 2.4kb super-enhancer containing a CGI (green) in the middle were sequenced to eliminate a possible ChIP bias of pulling down methylated regions. Both input and H3K27ac pull-down show nearly 100% methylation in these regions. See also Fig. S2.

Since our NOMe-seq and bisulfite sequencing assays cannot distinguish between methylation and hydroxymethylation at CpG sites, we performed hMeDIP (Active Motif #55010) at five of the bivalent regions. The hydroxymethylation enrichment in those regions is less than 1%, while the same regions show about 100% DNA methylation. Thus none of the regions show an enrichment in hydroxymethylation, indicating that the cytosine modification was predominantly 5-methylcytosine (Fig. S2F).

Overall, these findings reveal that enhancers carry active H3K27ac and inactive DNA methylation marks on the same molecules, showing a truly bivalent chromatin state.

Reduced binding of some but not all TFs at bivalent enhancers

The detailed study on the different types of enhancers suggests that TCF4 binding sites are unmethylated and accessible in enhancers (Fig. 1). We investigated the binding frequency of TCF4 at different methylation levels in enhancers in HCT116 cells (Fig. 3). Both regular and super-enhancers have less TCF4 binding at bivalent enhancer regions, although super-enhancer constituents are bound more frequently than regular enhancers even at increasing DNA methylation levels (Fig. 3A). Nevertheless, we investigated every TCF4 binding site in both enhancer types by plotting 1kb around the center of the binding site and ordered them from high to low average DNA methylation in HCT116 cells (Fig. 3B). Nearly all TCF4 sites are unmethylated and accessible in HCT116 cells (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained for YY-1 (Fig. S3A–C), a TF binding regulatory elements (Sigova et al., 2015), while AP-1, another factor that is predominantly binding enhancer regions (Spitz and Furlong, 2012) shows no preferential binding for monovalent or bivalent enhancers (Fig. S3D–F). The AP-1 motif contains a CpG site that can also be bound when methylated (Gustems et al., 2014), which may explain its binding at bivalent enhancers.

Fig. 3. TCF4 binding is reduced at bivalent enhancers.

(A) Bar graphs of the percentage of H3K27ac peaks bound by TCF4 in regular and super-enhancers in HCT116 cells. H3K27ac peaks are categorized into three methylation groups according to their average methylation level (<30, 30–70, >70). Peaks bound once by TCF4 are shown in blue, while those bound multiple times, are shown in green. (B) DNA methylation level at +−500bp of the TCF4 binding center in regular and super-enhancers. Every line indicates a TCF4 binding site in HCT116 cells that is maintained in the same order in (C). Every CpG site is indicated on a 0–100% methylation, green to red scale. The order shows the highest average DNA methylation at the top of the scatter plots. (C) Accessibility plots indicate GpC methylation levels from 0–100% accessible on a yellow to blue color scale. See also Fig. S3.

Since TCF4 and YY-1 binding is decreased at bivalent enhancers (Fig. 3A, S3A), we investigated whether the same phenomenon occurs for NDRs (Fig. S4A). NDRs are defined as M.CviPI methyltransferase accessible regions >100bp long (Lay et al., 2015). Indeed, bivalent regular and super-enhancer constituents have less NDRs than monovalent regions and bivalent super-enhancers have slightly more NDRs than regular bivalent enhancers (Fig. S4A).

Taken together, these results suggest that most probable regulatory regions of enhancers consist of small foci of unmethylated DNA and accessible chromatin where transcription factors can bind. In super-enhancers, these are embedded in a large hypermethylated and closed chromatin configured loci. Nevertheless, these functional unmethylated and accessible regions are dramatically decreased in bivlent regions, regardless of regular or super-enhancers.

H3K27ac is maintained by DNA methylation

To further understand the role of DNA methylation at bivalent regions, we tested whether they maintain the H3K27ac mark after loss of DNA methylation. We used ChIP-seq data from the highly demethylated DKO1 cell line and called enhancer regions the same way as for HCT116 cells. The resulting enhancer and super-enhancer constituents were then overlapped with the existing monovalent (<30% methylation) and bivalent (>70% methylation) regions in HCT116 cells (Fig. 4). Interestingly, about 60% of monovalent and less than 30% of bivalent regular enhancers are maintained in DKO1 cells (Fig. 4A, B & S4B, C). Similarly, 63% of monovalent and only 28% of bivalent super-enhancers are maintained in DKO1 cells (Fig. 4A, B & S4B, C). By directly plotting the H3K27ac enrichment and DNA methylation levels in HCT116 and DKO1 cell lines next to one another in the form of heatmaps, it is evident that at low methylation levels (<30%), the H3K27ac peak enrichment is positively correlated between both cell lines; however, at methylation levels >70%, the majority of peaks are anti-correlated for enrichment (Fig. S4C).

Fig. 4. DNA methylation maintains the H3K27ac mark at regular and super-enhancers.

(A) Bar graphs of the percentage of HCT116 H3K27ac peaks maintained in demethylated DKO1 cells for the category of lowly (<30%) and highly (>70%) methylated peaks. Dark blue percentages indicate regular enhancers in DKO1 cells, while light blue ones indicate super-enhancer constituents in DKO1 cells. A significant difference (***, p<0.001) in maintenance between lowly and highly methylated peaks was established in DKO1 cells for regular and super-enhancers. (B) Genome browser shots of regular (left) and super-enhancer (right) regions lost in DKO1 cells. The first track shows binding sites of TCF4 in purple. This is followed by a gene, CGI and called peaks (grey boxes) track in HCT116 and DKO1 cells. Wiggle plots of H3K27ac ChIP-seq enrichment in HCT116 and DKO1 cells with their respective NOMe-seq data are shown below. The DNA methylation NOMe-seq heatmap shows CpG methylation from low to high (green to red). See also Fig. S4B, C, S5F

The graphical example in Fig. 4B shows loss of H3K27ac in DKO1 cells even at unmethylated TCF4 binding sites, suggesting that H3K27ac cannot even be maintained in unmethylated transcription factor binding sites upon loss of surrounding methylation (Fig. 4B). Thus bivalent compared to monovalent enhancer regions in HCT116 cells are significantly lost (p<0.01) in DKO1 cells; suggesting that DNA methylation plays a stabilizing role at these bivalent enhancer regions to maintain the chromatin structure, which upon loss of methylation also loses the active H3K27ac mark.

Methylation and H3K27ac loss at bivalent regions

To validate our findings that DNA methylation stabilizes the H3K27ac mark with an additional approach and to possibly discover dynamic changes between DNA methylation and the H3K27ac mark, we transiently demethylated HCT116 cells with the methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-CdR). Cells were treated for 24h and were then maintained in drug-free medium for up to 14 days. We performed H3K27ac ChIP on control and treated samples and bisulfite sequenced 7 regular and super-enhancer constituent regions (Fig. 5 & S5A–E). The regions were chosen based on their substantial loss of H3K27ac in demethylated DKO1 cells (Fig. S5F) and their loss of DNA methylation after 5-Aza-CdR treatment in HCT116 cells. For all regions, the control input and H3K27ac pull-down samples have methylation levels up to 100%. Fourteen days after 5-Aza-CdR treatment, the input samples have lost up to 28% of their initial methylation level; however, the samples pulled-down by H3K27ac antibodies are almost completely methylated. This suggests that DNA methylation is required to maintain the active mark while the demethylated daughter strands have lost the H3K27ac mark. Thus, the active mark of enhancers was not maintained after loss of DNA methylation in bivalent regions, showing that an acute pharmacological treatment resulted in the same scenario as that seen in the long-term demethylated DKO1 cells. In addition, these results suggest that the bivalency might play a role in the structural integrity of potentially active enhancers marked with H3K27ac.

Fig. 5. H3K27ac remains on the methylated strand of bivalent enhancers and they regain DNA methylation after 5-Aza-CdR treatment.

(A–B) Input and H3K27ac ChIP DNA of control and 5-Aza-CdR-treated samples after 14 days of recovery were bisulfite converted and sequenced to show HCT116 regular (A) and super-enhancer (B) regions that are close to 100% methylation. At D14, the input samples have considerably lost their initial DNA methylation and are not marked by H3K27ac in DKO1 cells in our genome-wide data sets. The H3K27ac pull-down samples have barely changed. This shows that H3K27ac only remains on the methylated strand and is lost on the demethylated daughter strand. Every row shows a different clone and every circle a CpG site. White circles indicate unmethylated sites, while black circles are methylated CpG sites. (C) Boxplots of 7460 regular enhancers and 1124 super-enhancer constituents with an initial methylation level >70%. Their average CpG methylation level is shown at day 0 (control sample), 5, 25 and 42 after 5-Aza-CdR treatment. The original DNA methylation level is greatly re-gained at day 25. See also Fig. S5.

Bivalent enhancers regain methylation rapidly

The loss of bivalency upon pharmacological DNA demethylation might indicate that DNA methylation plays a role in controlling tissue specificity of bivalent enhancer regions. In this case, it would be essential for the cell to maintain this high DNA methylation level. Thus we measured the rate at which DNA methylation “rebounds” following transient demethylation induced by the 24h treatment with 5-Aza-CdR (Fig. 5C) for up to 42 days, as previously described (Yang et al., 2014). Nearly all bivalent regular and super-enhancers (Fig. 5C) regained their starting methylation levels (>70%) after 42 days, while some regain it as early as 5 to 25 days post-treatment (Fig. 5C). We previously showed that growth recovery of HCT116 cells is correlated with the DNA methylation rebound rate in gene bodies (Yang et al., 2014), which is comparable to the enhancers shown here. This fast methylation rebound (<42 days) re-establishes the original expression levels in the corresponding genes in HCT116 cells, which mostly belong to genes participating in oncogenic pathways (Yang et al., 2014). This result suggests that DNA methylation not only plays a role in controlling gene promoter (Jones, 2012) and body activity (Yang et al., 2014) but might also be responsible for maintaining regular and super-enhancers, by controlling chromatin integrity in their embedded regulatory regions.

Discussion

It has been difficult to determine whether DNA methylation is a cause or consequence of enhancer function and as Pott and Lieb (Pott and Lieb, 2014) point out, enhancer function can only be truly assessed by knock-out studies. Here, by focusing on the H3K27ac mark and DNA methylation, we have identified a bivalent chromatin signature at some enhancer regions that might maintain a potentially active enhancer state. This goes in hand with the appreciation that DNA methylation plays a dynamic role at the enhancer landscape; however, whether it actively evicts transcription factors from their binding sites or it rather fills in passively after transcription factors have left their binding site is still unclear (Calo and Wysocka, 2013) and should be further studied.

Although the recently released 850K MethylationEPIC BeadChip Infinium array now includes CpG sites in enhancer regions from the Fantom5 and ENCODE projects (Moran et al., 2015), we relied on whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data from our NOMe-seq samples that show that the active H3K27ac mark co-exists with the generally repressive DNA methylation mark in regular enhancers and over large regions of chromatin in super-enhancers (Fig. 1). An additional feature of these largely methylated domains in the HCT116 cells is the presence of punctuate demethylated transcription factor binding sites, which are accessible to the exogenously provided M.CviPI methyltransferase (Fig. 1). Presumably, these sites represent functional elements involved in gene expression control; they are sites for transcription factor binding and they show the expected inverse relationships between DNA methylation, H3K27ac and accessibility. Our results indicate that bivalent loci, with a positive correlation between DNA methylation and H3K27ac, are mainly found outside TF binding sites where chromatin accessibility is decreased. Our results were replicated in a recent publication, where average DNA methylation levels were investigated at super-enhancers. Similar to our results, they found hypo- and hyper-methylated super-enhancers with regional unmethylated TFBS (Heyn et al., 2016).

Removal of most cytosine methylation in DKO1 cells has a dramatic effect on bivalent enhancer structures and leads to a strong decrease in the H3K27ac mark in DKO1 cells, which was also confirmed via DNA demethylation induced by transient 5-Aza-CdR treatment. Our findings differ from other reports that DNA methylation negatively influences the level of H3K27ac at enhancers (Xie et al., 2013). Although it has been suggested that DNA methylation is causally related to keeping transcription factor binding sites well defined (Calo and Wysocka, 2013), it has not yet been directly demonstrated. Our findings show that this concept might be true. A recent study has shown that super-enhancers can collapse entirely if one H3K27ac-enriched constituent is removed or a transcription factor is no longer binding (Hnisz et al., 2015; Loven et al., 2013; Mansour et al., 2014). Here we show that an additional factor, namely DNA methylation can have a similar effect on both, regular and super-enhancer regions when it is removed genetically or transiently. Not only do the bivalent regions lose H3K27ac upon loss of DNA methylation but one could speculate that transcription factor binding might be lost, assuming that surrounding DNA methylation guided the factors to their specific unmethylated target sequences.

Our previous work, studying the rate at which DNA methylation rebounds following transient treatment of HCT116 cells with 5-Aza-CdR, showed that CpG sites located within gene bodies and marked with H3K36me3 had the greatest propensity for remethylation (Yang et al., 2014). The rate of remethylation of enhancers matches that of gene bodies, suggesting that restoration of the bivalent chromatin state is of importance for proper enhancer function.

A particularly striking observation was the association between the active histone mark with the heavily methylated CpG islands in super-enhancers, two features that have until now, always been seen as being mutually exclusive. Indeed, we observe that the active allele of the CDKN2A promoter is unmethylated and acetylated and the methylated allele is devoid of acetylation. The mechanism underlying the coexistence of the two marks to create a bivalent state remains unknown and needs to be further studied.

The term “bivalency” was coined to describe the presence of both the inactive H3K27me3 and active H3K4me3 marks at polycomb repressed promoters in embryonic stem cells (Bernstein et al., 2006). Recently, another bivalent chromatin mark has been introduced by Matsumura et al, where H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 domains exist at promoters of mesenchymal stem cells (Matsumura et al., 2015). This unexpected existence of a bivalent state at enhancers with or without CpG islands has, to our knowledge, not been reported and may be exclusively an enhancer characteristic that does not exist at gene promoters or other functional elements. DNA methylation might ensure structural integrity at bivalent enhancers by continuously guiding the H3K27ac-attracted transcription factors to their specific hypomethylated binding sites.

These findings create different therapeutic strategy possibilities, considering the fact that one enhancer can regulate multiple genes and thus potential inactivation of a bivalent enhancer with demethylating agents could induce dramatic expression changes of their target genes.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and drug treatment

HCT116 and DKO1 cells (Rhee et al., 2002) were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified and 5% CO2 enriched atmosphere. HCT116 cells were obtained from ATCC and DKO1 cells were a gift from Drs Vogelstein and Baylin.

For drug treatment, 0.3 µM of 5-Aza-CdR (Sigma-Aldrich) were prepared in PBS and added to 3*105 HCT116 cells. The drug-containing medium was removed after 24 hours and fresh medium was added to the cells. Cells were cultured and harvested at days 5, 24 and 42 for downstream experiments.

ChIP

ChIP was performed as previously described and to ENCODE standards (Kelly et al., 2010; Landt et al., 2012). Experiments included the following antibody: anti-H3K27ac (Active Motif 39133). Antibody specificity was confirmed in (Rothbart et al., 2015). Libraries were created, barcoded and sequenced according to (Barski et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2012).

ChIP-seq

All ChIP-seq data were processed as follows: single-end reads were extended to 200bp, duplicate reads were removed and only mapped reads were retained. H3K27ac peaks were called with the MACS algorithm at a p value cutoff of 10−10 against input (Zhang et al., 2008). The average size of the sonicated fragments was 200bp. Called peaks that were less than 5bp apart from each other, were combined into one peak and only peaks that were common among the biological replicates were retained. Peaks called +/−1500bp of TSSs were considered in the TSS group and the rest were considered as potential enhancer regions. Quantification of peaks was performed through a read count quantification, with correction towards the largest data store and peak width. Resulting values were log2 transformed.

ChIP bisulfite sequencing

HCT116 H3K27ac ChIP samples were bisulfite converted with the Zymo EZ DNA Methylation™ Kit according to manufacturer’s protocol. Enhancer regions of interest were then PCR amplified and cloned with the TOPO® TA Cloning® Kit for Sequencing, with One Shot® TOP10 Chemically Competent E. coli cells according to manufacturer’s protocol. Plasmids with successful region integration were amplified with the illustra TempliPhi kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to manufacutrer’s protocol and sequenced with the M13 reverse primer.

hMeDIP

Genomic DNA from HCT116 cells was tested for hydroxymethylation enrichment at enhancer regions with the hMeDIP kit from Active Motif according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 20ug of genomic DNA were sheared by sonication to 200–600bp fragments. A 10% input sample (50ng) was set aside to be used later in the qRT-PCR reaction to create primer-specific standard curves. Other control DNA samples include an unmethylated, fully methylated and fully hydroxymethylated APC control fragment for which primers are provided in the kit. The control regions are spiked into the sheared DNA at a 1:20000 ration. 500ng of sheared test sample and control DNA were then incubated overnight with either the 5-hydroxymethylcytidine or IgG antibody. DNA was captured with protein G magnetic beads, followed by several wash steps and elution. DNA was treated with Proteinase K and column purified with the MinElute PCR Purification Kit from Qiagen. QRT-PCR was performed with APC control and test primers. Hydroxymethylation enrichment was calculated from the standard curves performed with genomic and spike DNA input samples.

Super-enhancer calling

Super-enhancers had been called previously by the Young laboratory for the HCT116, MCF7 and HMEC cells (Hnisz et al., 2013). In all other cells, super-enhancers were called with the HOMER algorithm. Briefly, tag directories were created with makeTagDirectory from ChIP-seq data for H3K27ac and input. Then the findPeaks algorithm was used to call enhancer regions with the following options: -style super and – L 1. These super-enhancer coordinates were then used to determine the individual constituents that fall into those regions, previously detected with the MACS algorithm.

NOMe-seq and NDR calling

NOMe-seq data was processed as previously described (Kelly et al., 2010). Genome-wide NOMe-seq data of 5-Aza-CdR-treated HCT116 cells was performed and processed as previously described (Kelly et al., 2012; Lay et al., 2015). NDRs from two HCT116 cell replicates were calculated based on methylatransferase accessible regions (MARs) >100bp long, as previously described (Lay et al., 2015). MARs smaller than 100bp are just called “accessible”.

Intersection of ChIP-seq and NOMe-seq data

Endogenous DNA methylation and GpC methylation files were intersected via BedTools (http://bedtools.readthedocs.org/en/latest/index.html) with enhancer coordinates from ChIP-seq data to obtain base pair resolution of DNA methylation at CpG/GpC sites in enhancer regions.

Accession Numbers

NOMe-seq data of HCT116 and DKO1 cells were previously generated by (Lay et al., 2015) and downloaded from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (GSE58638). NOMe-seq of 5-Aza-CdR treated HCT116 cells have been submitted to GEO under the accession number GSE68046. NOME-seq and ChIP-seq data for MCF7, HMEC and PREC cells were obtained from GSE57498. WGBS data for normal colon was obtained from (Berman et al., 2012) under (PHS000385). Colonic mucosa ChIP-seq data was downloaded from the Roadmap project (http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org/) and have past their 9-months moratorium. Input: GSM621669; H3K27ac: published by (Zhu et al., 2013). ChIP-seq data of H3K27ac and H3K4me1 in HCT116 and DKO1 cells were obtained from (Lay et al., 2015) under the accession number GSE58638. TCF4 CHIP-seq data in HCT116 cells was downloaded from GSM782123, YY-1 data from UCSC-ENCODE-hg19:wgEncodeEH001671 and AP-1 data from UCSC-ENCODE-hg19:wgEncodeEH003216.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

H3K27ac and DNA methylation “bivalency” exists at enhancers but not at promoters

Some but not all TFs have decreased binding at bivalent enhancers

Bivalent enhancers have fewer NDRs than monovalent regions

Bivalent enhancers lose H3K27ac upon removal of DNA methylation

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by R01CA082422 (P.A.J) and R01CA083867 (P.A.J. and G.L). J.C was funded by a postdoctoral AFR grant from the Fonds National de la Recherche Luxembourg. K.M was supported by a grant from The Danish Strategic Research Council. We thank Heather Witt from the Dr Peggy Farnham laboratory for making HCT116 and DKO1 cell line ChIP-seq replicates available and we thank Dr Yaping Liu for pre-processing of NOMe-seq data and NDR calling.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

JC performed the computational analysis, loci-specific bisulfite sequencing, NOMe-seq on 5-Aza-CdR treated HCT116 cells and wrote the manuscript. CED created bisulfite sequencing diagrams of enhancer regions and gave bioinformatical guidance. FL provided ChIP-seq and NOMe-seq data. KM prepared PC3 NOMe-seq samples and KDS provided supervision and funding. GL and PAJ funded experiments and gave scientific guidance.

References

- Andersson R, Gebhard C, Miguel-Escalada I, Hoof I, Bornholdt J, Boyd M, Chen Y, Zhao X, Schmidl C, Suzuki T, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature. 2014;507:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus-Hill ML, Elbert KM, Hidalgo J, Capecchi MR. T-cell factor 4 functions as a tumor suppressor whose disruption modulates colon cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:4914–4919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aran D, Hellman A. DNA methylation of transcriptional enhancers and cancer predisposition. Cell. 2013;154:11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman BP, Weisenberger DJ, Aman JF, Hinoue T, Ramjan Z, Liu Y, Noushmehr H, Lange CP, van Dijk CM, Tollenaar RA, et al. Regions of focal DNA hypermethylation and long-range hypomethylation in colorectal cancer coincide with nuclear lamina-associated domains. Nature genetics. 2012;44:40–46. doi: 10.1038/ng.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulger M, Groudine M. Functional and mechanistic diversity of distal transcription enhancers. Cell. 2011;144:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calo E, Wysocka J. Modification of enhancer chromatin: what, how, and why? Molecular cell. 2013;49:825–837. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R, Zhang Y. SUZ12 is required for both the histone methyltransferase activity and the silencing function of the EED-EZH2 complex. Molecular cell. 2004;15:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger G, Jeong S, Escobar SG, Cortez CC, Li TW, Saito Y, Yoo CB, Jones PA, Liang G. Identification of DNMT1 (DNA methyltransferase 1) hypomorphs in somatic knockouts suggests an essential role for DNMT1 in cell survival. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:14080–14085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604602103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustems M, Woellmer A, Rothbauer U, Eck SH, Wieland T, Lutter D, Hammerschmidt W. c-Jun/c-Fos heterodimers regulate cellular genes via a newly identified class of methylated DNA sequence motifs. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:3059–3072. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, Fu Y, Ching CW, Hawkins RD, Barrera LO, Van Calcar S, Qu C, Ching KA, et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nature genetics. 2007;39:311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Molecular cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn H, Vidal E, Ferreira HJ, Vizoso M, Sayols S, Gomez A, Moran S, Boque-Sastre R, Guil S, Martinez-Cardus A, et al. Epigenomic analysis detects aberrant super-enhancer DNA methylation in human cancer. Genome biology. 2016;17:11. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0879-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lee TI, Lau A, Saint-Andre V, Sigova AA, Hoke HA, Young RA. Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell. 2013;155:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D, Schuijers J, Lin CY, Weintraub AS, Abraham BJ, Lee TI, Bradner JE, Young RA. Convergence of developmental and oncogenic signaling pathways at transcriptional super-enhancers. Molecular cell. 2015;58:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon GC, Rajagopal N, Shen Y, McCleary DF, Yue F, Dang MD, Ren B. Epigenetic memory at embryonic enhancers identified in DNA methylation maps from adult mouse tissues. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1198–1206. doi: 10.1038/ng.2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon GC, Song CX, Du T, Jin F, Selvaraj S, Lee AY, Yen CA, Ye Z, Mao SQ, Wang BA, et al. 5mC Oxidation by Tet2 Modulates Enhancer Activity and Timing of Transcriptome Reprogramming during Differentiation. Molecular cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TK, Liu Y, Lay FD, Liang G, Berman BP, Jones PA. Genome-wide mapping of nucleosome positioning and DNA methylation within individual DNA molecules. Genome research. 2012;22:2497–2506. doi: 10.1101/gr.143008.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TK, Miranda TB, Liang G, Berman BP, Lin JC, Tanay A, Jones PA. H2A.Z maintenance during mitosis reveals nucleosome shifting on mitotically silenced genes. Molecular cell. 2010;39:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Tada M, Nakatsuji N, Tada T. Histone code modifications on pluripotential nuclei of reprogrammed somatic cells. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:5710–5720. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5710-5720.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi M, Baguet A, Martens J, Margueron R, Jenuwein T, Bix M. EZH2 and histone 3 trimethyl lysine 27 associated with Il4 and Il13 gene silencing in Th1 cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:31470–31477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landt SG, Marinov GK, Kundaje A, Kheradpour P, Pauli F, Batzoglou S, Bernstein BE, Bickel P, Brown JB, Cayting P, et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome research. 2012;22:1813–1831. doi: 10.1101/gr.136184.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay FD, Liu Y, Kelly TK, Witt H, Farnham PJ, Jones PA, Berman BP. The role of DNA methylation in directing the functional organization of the cancer epigenome. Genome research. 2015 doi: 10.1101/gr.183368.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Erkek S, Tong Y, Yin L, Federation AJ, Zapatka M, Haldipur P, Kawauchi D, Risch T, Warnatz HJ, et al. Active medulloblastoma enhancers reveal subgroup-specific cellular origins. Nature. 2016;530:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature16546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loven J, Hoke HA, Lin CY, Lau A, Orlando DA, Vakoc CR, Bradner JE, Lee TI, Young RA. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell. 2013;153:320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour MR, Abraham BJ, Anders L, Berezovskaya A, Gutierrez A, Durbin AD, Etchin J, Lawton L, Sallan SE, Silverman LB, et al. Oncogene regulation. An oncogenic super-enhancer formed through somatic mutation of a noncoding intergenic element. Science. 2014;346:1373–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1259037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y, Nakaki R, Inagaki T, Yoshida A, Kano Y, Kimura H, Tanaka T, Tsutsumi S, Nakao M, Doi T, et al. H3K4/H3K9me3 Bivalent Chromatin Domains Targeted by Lineage-Specific DNA Methylation Pauses Adipocyte Differentiation. Molecular cell. 2015;60:584–596. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran S, Arribas C, Esteller M. Validation of a DNA methylation microarray for 850,000 CpG sites of the human genome enriched in enhancer sequences. Epigenomics. 2015 doi: 10.2217/epi.15.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myohanen SK, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Hypermethylation can selectively silence individual p16ink4A alleles in neoplasia. Cancer research. 1998;58:591–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord AS, Blow MJ, Attanasio C, Akiyama JA, Holt A, Hosseini R, Phouanenavong S, Plajzer-Frick I, Shoukry M, Afzal V, et al. Rapid and pervasive changes in genome-wide enhancer usage during mammalian development. Cell. 2013;155:1521–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SC, Stitzel ML, Taylor DL, Orozco JM, Erdos MR, Akiyama JA, van Bueren KL, Chines PS, Narisu N, Program NCS, et al. Chromatin stretch enhancer states drive cell-specific gene regulation and harbor human disease risk variants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:17921–17926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317023110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pott S, Lieb JD. What are super-enhancers? Nature genetics. 2014;47:8–12. doi: 10.1038/ng.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada-Iglesias A, Bajpai R, Swigut T, Brugmann SA, Flynn RA, Wysocka J. A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature. 2011;470:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature09692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee I, Bachman KE, Park BH, Jair KW, Yen RW, Schuebel KE, Cui H, Feinberg AP, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, et al. DNMT1 and DNMT3b cooperate to silence genes in human cancer cells. Nature. 2002;416:552–556. doi: 10.1038/416552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart SB, Dickson BM, Raab JR, Grzybowski AT, Krajewski K, Guo AH, Shanle EK, Josefowicz SZ, Fuchs SM, Allis CD, et al. An Interactive Database for the Assessment of Histone Antibody Specificity. Molecular cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serandour AA, Avner S, Oger F, Bizot M, Percevault F, Lucchetti-Miganeh C, Palierne G, Gheeraert C, Barloy-Hubler F, Peron CL, et al. Dynamic hydroxymethylation of deoxyribonucleic acid marks differentiation-associated enhancers. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:8255–8265. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigova AA, Abraham BJ, Ji X, Molinie B, Hannett NM, Guo YE, Jangi M, Giallourakis CC, Sharp PA, Young RA. Transcription factor trapping by RNA in gene regulatory elements. Science. 2015;350:978–981. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz F, Furlong EE. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2012;13:613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrg3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler MB, Murr R, Burger L, Ivanek R, Lienert F, Scholer A, van Nimwegen E, Wirbelauer C, Oakeley EJ, Gaidatzis D, et al. DNA-binding factors shape the mouse methylome at distal regulatory regions. Nature. 2011;480:490–495. doi: 10.1038/nature10716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taberlay PC, Kelly TK, Liu CC, You JS, De Carvalho DD, Miranda TB, Zhou XJ, Liang G, Jones PA. Polycomb-repressed genes have permissive enhancers that initiate reprogramming. Cell. 2011;147:1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taberlay PC, Statham AL, Kelly TK, Clark SJ, Jones PA. Reconfiguration of nucleosome-depleted regions at distal regulatory elements accompanies DNA methylation of enhancers and insulators in cancer. Genome research. 2014;24:1421–1432. doi: 10.1101/gr.163485.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Maurano MT, Qu H, Varley KE, Gertz J, Pauli F, Lee K, Canfield T, Weaver M, Sandstrom R, et al. Widespread plasticity in CTCF occupancy linked to DNA methylation. Genome research. 2012;22:1680–1688. doi: 10.1101/gr.136101.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA, Schones DE, Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Peng W, Zhang MQ, et al. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nature genetics. 2008;40:897–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte WA, Orlando DA, Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lin CY, Kagey MH, Rahl PB, Lee TI, Young RA. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell. 2013;153:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiench M, John S, Baek S, Johnson TA, Sung MH, Escobar T, Simmons CA, Pearce KH, Biddie SC, Sabo PJ, et al. DNA methylation status predicts cell type-specific enhancer activity. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:3028–3039. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Schultz MD, Lister R, Hou Z, Rajagopal N, Ray P, Whitaker JW, Tian S, Hawkins RD, Leung D, et al. Epigenomic analysis of multilineage differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2013;153:1134–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Han H, De Carvalho DD, Lay FD, Jones PA, Liang G. Gene body methylation can alter gene expression and is a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer cell. 2014;26:577–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome biology. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Adli M, Zou JY, Verstappen G, Coyne M, Zhang X, Durham T, Miri M, Deshpande V, De Jager PL, et al. Genome-wide chromatin state transitions associated with developmental and environmental cues. Cell. 2013;152:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.