Abstract

Fentanyl is an addictive prescription opioid that is over 80 times more potent than morphine. The synthetic nature of fentanyl has enabled the creation of dangerous ‘designer drug’ analogues that escape toxicology screening, yet display comparable potency to the parent drug. Alarmingly, a large number of fatalities have been linked to overdose of fentanyl derivatives. Herein, we report an effective immunotherapy for reducing the psychoactive effects of fentanyl class drugs. A single conjugate vaccine was created that elicited high levels of antibodies with cross-reactivity for a wide panel of fentanyl analogues. Moreover, vaccinated mice gained significant protection from lethal fentanyl doses. Lastly, a surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based technique was established enabling drug specificity profiling of antibodies derived directly from serum. Our newly developed fentanyl vaccine and analytical methods may assist in the battle against synthetic opioid abuse. Fentanyl is an effective synthetic opioid that is used legally as a schedule II prescription pain reliever. However, fentanyl presents a significant abuse liability due to the euphoric feeling it induces via activation of μ-opioid receptors (MOR) in the brain; the same pharmacological target as the illegal schedule I opioid, heroin.[1] Excessive activation of MOR results in respiratory depression which can be fatal.[2] Fentanyl exceeds the potency of heroin by >10-fold, and morphine by >80-fold posing a significant risk of overdose when it is consumed from unregulated sources.[3] Furthermore, the ease of fentanyl synthesis enables illegal production and the creation of designer drug analogues.[4] The fact that the pharmacology of these analogues has yet to be properly characterized makes them particularly dangerous, especially when certain modifications, even methyl additions, can increase potency, notably at the 3-position (Figure 1).[5]

Keywords: fentanyl, conjugate vaccine, immunology, antibody, biosensors

Last July, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) reported an alarming surge in fentanyl overdose deaths:[6] the latest update in a long stream of overdose cases starting with α-methylfentanyl aka “China White” in the late 1980s.[7] A newer designer analogue, acetylfentanyl, further exacerbates the opioid epidemic because of its deceptive sale as heroin or as a heroin mixture,[8] and it has been linked to a number of overdose deaths.[9] In addition to the US, fentanyl abuse is on the rise across Europe; while the most overdose deaths occurred in Estonia, the highest consumption of fentanyl per capita was reported in Germany and Austria.[10]

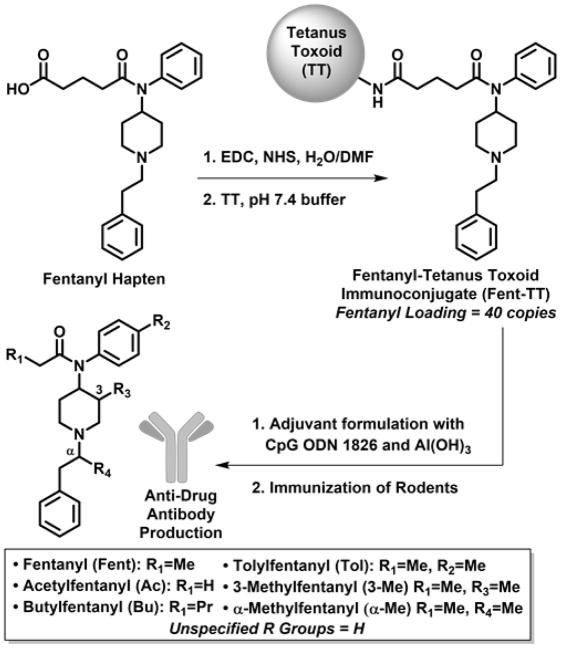

To combat the harmful and addictive effects of fentanyl and its analogues, we pursued an immunopharmacotherapeutic approach, similar to previous campaigns for addiction therapeutics against cocaine,[11] nicotine,[12] methamphetamine[13] and heroin.[14] The basis of this strategy involves active vaccination of a protein-drug conjugate to generate an in vivo ‘immunoantagonist’, which effectively minimizes concentrations of the target drug at the sites of action. As a result, the vaccine reduces the addiction liability and overdose potential of the specific drug. In this work, we report the first instance of an efficacious fentanyl conjugate vaccine. Upon immunization, this vaccine successfully stimulated endogenous generation of IgG antibodies with specificity for fentanyl class drugs. Moreover, mouse antiserum showed nanomolar affinity for a variety of fentanyl analogues by SPR-analytical methods. When mice were dosed with potentially lethal quantities of fentanyl analogues, the vaccine imparted significant protection. No other vaccines to date have demonstrated blockade of the acutely lethal effects of any drugs of abuse. Importantly, our research efforts have yielded significant progress for mitigating the pharmacodynamic effects of fentanyl class drugs. In developing a fentanyl vaccine, hapten design presented the initial and possibly the most crucial challenge. As we have reported previously, small molecule haptens must faithfully preserve the natural structure of the target molecule to make a successful immunoconjugate.[15] Confronted not only with fentanyl, but also designer analogues, our hapten incorporated the core N-(1-phenethylpiperidin-4-yl)-N-phenylacetamide scaffold to achieve broad immune specificity for virtually all fentanyl derivatives. With this mindset, the propanoyl group in fentanyl was selected as the point of linker attachment because it would not sterically encumber the core structure (Figure 1). Ultimately, hapten design was accomplished by replacing the propanoyl group in fentanyl with a glutaric acid moiety. The added carboxyl group enabled N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester formation for bioconjugation of the hapten[16] to an immunogenic carrier protein (Figure 1). This reliable amide coupling reaction is a standard method for generating hapten-protein conjugates,[12c, 17] facilitating high loading of fentanyl onto bovine serum albumin (BSA) and tetanus toxoid (TT) proteins through surface lysine residues; 38 and 40 copies were obtained, respectively, as assessed by MALDI-TOF spectra (Figure S1a/b). Of the two conjugates, the fentanyl-TT conjugate (Fent-TT, Figure 1) was chosen for immunization because TT is a component of clinically-approved tetanus and glycoconjugate vaccines. For vaccine formulation, Fent-TT was combined with adjuvants Al(OH)3 (alum) and CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) 1826 which have proven effective in boosting IgG antibody responses to a heroin conjugate vaccine.[14a] When mice were immunized with the Fent-TT vaccine, it induced very high anti-fentanyl antibody midpoint titers by ELISA of >100,000 (Figure 2), providing ample in vivo neutralization capacity for a variety of fentanyls (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Construction of fentanyl immunoconjugate and structures of fentanyl analogues recognized by polyclonal antibodies.

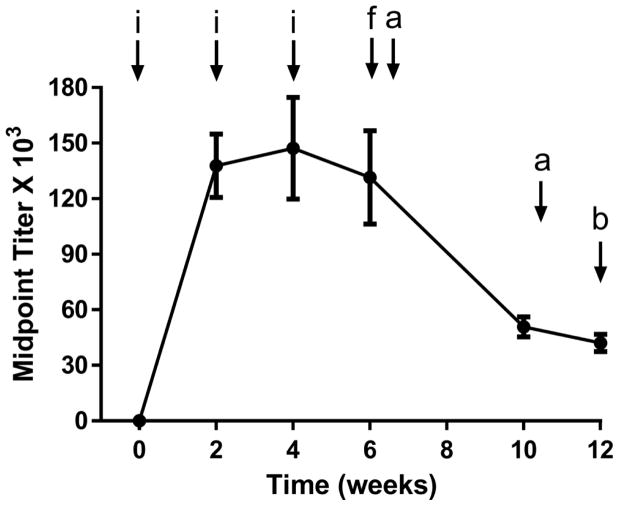

Figure 2.

Timeline of experiments and anti-fentanyl antibody titers. Fent-TT (50 μg) was formulated with alum (750 μg) + CpG ODN 1826 (50 μg) and administered i.p. to each mouse (N=6). IgG titers were determined by ELISA against fentanyl-BSA conjugate. Points denote means ± SEM. Key: i=vaccine injection, a=antinociception assay, f=affinity determination by SPR b=blood/brain biodistribution study.

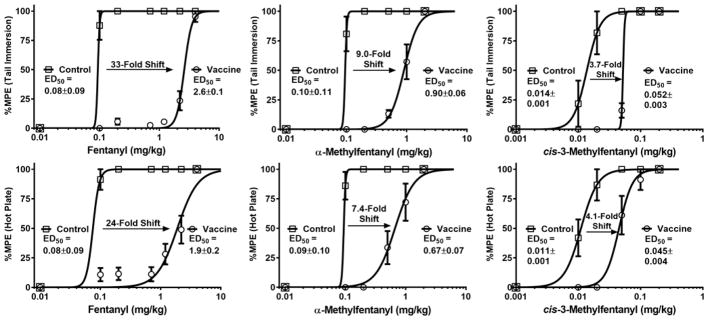

To assess vaccine performance, we employed antinociception assays that are a standard method for measuring the analgesic potential of opioid drugs in rodent models;[14a, 18] opioids such as fentanyl increase pain thresholds in a dose-responsive manner, and these thresholds can be quantified by measuring animal latency to nociception induced by a hot surface. A drug vaccine will blunt the pharmacological action of the target drug via serum antibody-mediated immunoantagonism of an administered dose; therefore, a successful vaccine should shift the drug dose-response curve in antinociception assays to the ‘right’. Comparison of drug ED50 doses in vaccinated and non-vaccinated mice serves as a useful metric for drug vaccine efficacy. Previously, we have reported vaccine-induced shifts of about 5 to 10-fold which caused heroin-dependent rats to extinguish drug self-administration.[14a, 14b] In the current study, we observed large fentanyl ED50 shifts of over 30-fold. Remarkably, during the initial week 6 testing session, fentanyl dosing was incapable of overriding the protective capacity of the vaccine (Figure S2). One month later (week 10), anti-drug titers in vaccinated mice had decreased to a point where smaller fentanyl doses could be used to generate full dose-response curves for ED50 determination; large vaccine-mediated shifts were observed (33-fold in the tail immersion test, Figure 3). Strikingly, at the two largest doses that were safely administered to vaccinated mice (2.2 and 4.4 mg/kg), untreated mice experienced a 18 and 55% fatality rate respectively, thus demonstrating the ability of the vaccine to block lethal fentanyl doses.

Figure 3.

Fentanyl analogue dose-response curves and ED50 values in antinociception assays. Vaccinated and control mice (N=6 each) were cumulatively dosed with the specified drug and latency to nociception was measured by tail immersion (top) and hot plate (bottom) tests. Points denote means ± SEM expressed as a percentage of the maximum possible drug effect (%MPE). For all three drugs, p-values were <0.001 in comparing control vs. vaccine groups by an unpaired t test.

As a testament to the vaccine’s ability to neutralize other fentanyl analogues, Fent-TT immunized mice showed protection from two of the most common illegal fentanyl derivatives, 3-methylfentanyl and α-methylfentanyl aka “China White” (see Figure 1 for structures). The α-Me analogue was equipotent with the parent compound, and the vaccine was able to shift the α-Me ED50 by about 8-fold (Figure 3). On the other hand, the 3-Me analogue was extraordinarily potent (about 10-fold greater than fentanyl), yet the vaccine still produced a 4-fold ED50 shift (Figure 3). Overall, our behavioral results indicate that the Fent-TT vaccine provided ample attenuation of large fentanyl doses in vivo while demonstrating a therapeutically useful level of cross-reactivity to fentanyl analogues. Clinically, these results implicate Fent-TT as an effective addiction therapy for curbing fentanyl abuse and overdose-induced lethality.

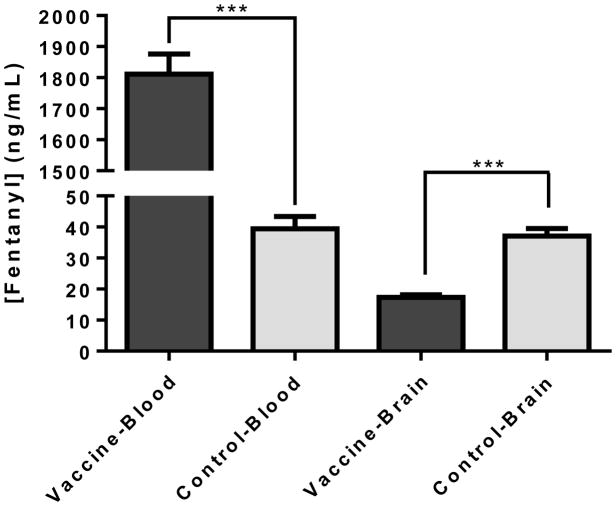

From a pharmacokinetic standpoint, we investigated the effect of the Fent-TT vaccine on the biodistribution of a fentanyl dose. Following administration of a fentanyl dose, we sacrificed both control and vaccinated mice at roughly the tmax (time at peak drug plasma concentrations) and measured fentanyl concentrations in both brain and blood samples by LCMS. Our results clearly show how serum antibodies in vaccinated mice act as a depot to bind 45-times the amount of fentanyl relative to serum proteins in control mice. This translated to a significant reduction in fentanyl brain concentrations of vaccinated mice, lending to a pharmacological explanation of how the vaccine attenuates fentanyl psychoactivity.

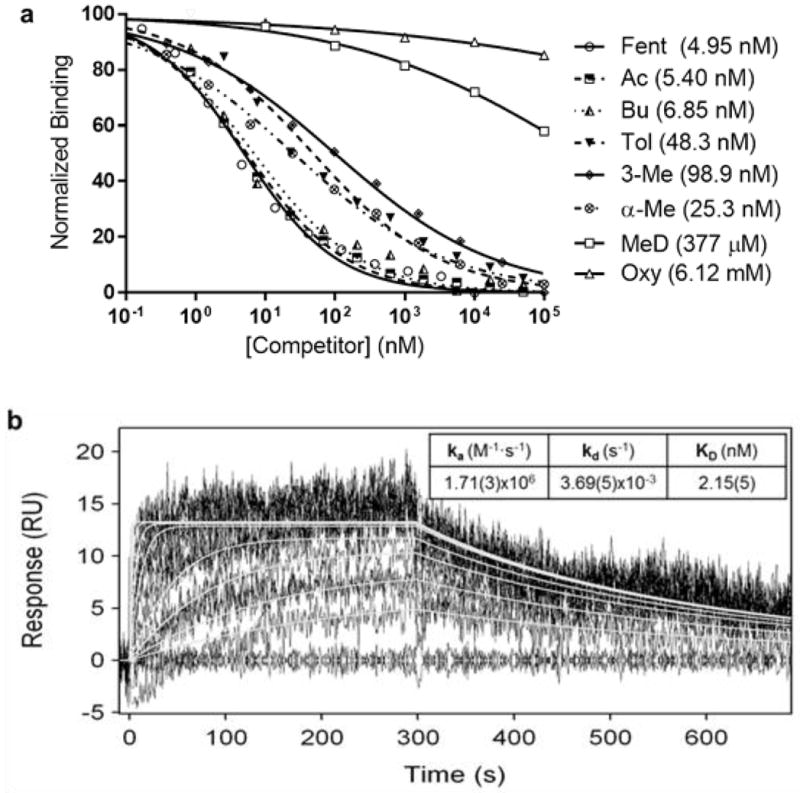

Behavioral and pharmacokinetic results were corroborated with thorough biochemical analysis of antiserum derived from Fent-TT vaccinated mice. To achieve this, we employed surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy, a highly sensitive technique for investigating protein-protein or protein-small molecule binding interactions.[19] In a new application of SPR, we measured binding affinities of polyclonal antibodies in vaccinated mouse serum for various fentanyl analogues. Diluted mouse serum was preincubated with a series of concentrations of selected fentanyl derivatives and then injected into a Biacore 3000 containing a Fent-BSA coated chip. Essentially, this method is a more sophisticated version of competitive ELISA in which serially-diluted free drug competes with an immobilized drug hapten for antibody binding.[20] Our results from the SPR competition experiment (Figure 5a) indicated that antibodies from Fent-TT immunized mice have high affinity for fentanyl derivatives, generating binding curves with low nanomolar IC50 values and limits of detection in the pM range (see Figure 5a and raw sensorgrams, Figure S3). Relative affinities between analogues with different R1 alkyl groups were very similar, likely due to the fact that the R1 position was used as a linker attachment point. As expected, methylation at other positions resulted in lower affinity but still IC50 values were <100 nM. Furthermore, the SPR IC50s mirrored the results in behavioral assays, and in both cases followed a trend of Fent>α-Me>cis-3-Me. Since the Fent-TT vaccine gave broad specificity to fentanyl class drugs, two clinically used opioids methadone (MeD) and oxycodone (Oxy) were tested to ensure minimal cross reactivity. Indeed, affinities for these opioids were >7,500 times lower compared to fentanyl (Figure 5a), demonstrating that they could still be used in Fent-TT vaccinated subjects.

Figure 5.

Antiserum opioid binding curves and SPR sensorgrams. a) Diluted mouse serum from week 6 was incubated with serial dilutions of the listed opioids and injected into a Biacore 3000 containing a Fent-BSA loaded sensor chip. Signal produced by antibody binding to the SPR chip without drug present was used as a reference for 100% binding. Fentanyls used were racemic and 3-Me was cis. See Figure 1 for structures. b) Overlaid plots of sensorgrams obtained for the interaction between fentanyl (1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5, 31.25, 15.63, 7.81, 3.9, 1.95 and 0 nM) and immobilized anti-fentanyl antibodies at 25 °C on a BiOptix 404pi. Original experimental sensorgrams are shown in black and fitted curves are traced in white.

Further validation of the SPR method was pursued to confirm that the generated IC50 values were representative of actual KD; hapten affinity does not always reflect free drug affinity. To address this problem, we affinity purified anti-fentanyl antibodies and loaded them onto an SPR chip for direct measurement of free fentanyl binding kinetics. As shown in Figure 5b sensorgrams, the fentanyl KD of purified antibodies (2 nM), is in close agreement with the IC50 value determined by the competition method (5 nM). Thus, we have demonstrated the SPR competition method as an accurate way to measure drug affinities of polyclonal serum antibodies. A crucial aspect of immunopharmacotherapy is proper characterization of anti-drug antibodies, and the SPR method could help to facilitate this facet of drug vaccine development. Additionally, the method could be used to screen biological samples e.g. blood or urine for the presence of a wide variety of fentanyl derivatives, especially since the limit of detection for many fentanyl analogues is <1 nM (Figure 5a, Figure S3).

The current study has yielded a potential therapeutic that could assist in combatting the rise of opioid abuse. An effective fentanyl conjugate vaccine was developed that easily ablates small doses needed to achieve a normal drug-induced ‘high’ but also attenuates large, potentially lethal doses of fentanyl class drugs. Furthermore, the success of this vaccine’s design helps to advance immunopharmacotherapy from an academic novelty towards a practical therapy, and influences the creation of vaccines against other designer drugs.[4, 21]

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

Biodistribution of fentanyl in blood and brain samples. Vaccinated and control mice (N=6 each) were dosed with 0.2 mg/kg fentanyl and tissue was harvested 15 min post-injection. Fentanyl quantification was performed by LCMS analysis. Bars denote means + SEM. *** p < 0.001, unpaired t test.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institute on Drug Addiction for funding (grants R21DA039634, F31DA037709) and Dr. Michael Taffe for providing DEA licensing (RT0485537). This is manuscript # 29249 from TSRI.

References

- 1.Janssen PA. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1962;34:260–268. doi: 10.1093/bja/34.4.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White JM, Irvine RJ. Addiction. 1999;94:961–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson GL. J Forensic Sci. 1991;36:422–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll FI, Lewin AH, Mascarella SW, Seltzman HH, Reddy PA. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 2012;1248:18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Bever WF, Niemegeers CJ, Janssen PA. J Med Chem. 1974;17:1047–1051. doi: 10.1021/jm00256a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NIDA. Emerging Trends. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin M, Hecker J, Clark R, Frye J, Jehle D, Lucid EJ, Harchelroad F. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:158–164. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stogner JM. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:637–639. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.C. Centers for Disease, Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:703–704. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mounteney J, Giraudon I, Denissov G, Griffiths P. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:626–631. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Martell BA, Mitchell E, Poling J, Gonsai K, Kosten TR. Biol Psych. 2005;58:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Carrera MRA, Ashley JA, Zhou B, Wirsching P, Koob GF, Janda KD. PNAS. 2000;97:6202–6206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Pravetoni M, Keyler DE, Pidaparthi RR, Carroll FI, Runyon SP, Murtaugh MP, Earley CA, Pentel PR. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lockner JW, Lively JM, Collins KC, Vendruscolo JCM, Azar MR, Janda KD. J Med Chem. 2015;58:1005–1011. doi: 10.1021/jm501625j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Collins KC, Janda KD. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014;25:593–600. doi: 10.1021/bc500016k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Moreno AY, Mayorov AV, Janda KD. JACS. 2011;133:6587–6595. doi: 10.1021/ja108807j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ruedi-Bettschen D, Wood SL, Gunnell MG, West CM, Pidaparthi RR, Carroll FI, Blough BE, Owens SM. Vaccine. 2013;31:4596–4602. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Bremer PT, Schlosburg JE, Lively JM, Janda KD. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:1075–1080. doi: 10.1021/mp400631w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schlosburg JE, Vendruscolo LF, Bremer PT, Lockner JW, Wade CL, Nunes AA, Stowe GN, Edwards S, Janda KD, Koob GF. PNAS. 2013;110:9036–9041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219159110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Janda KD, Treweek JB. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2012;12:67–72. doi: 10.1038/nri3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Jalah R, Torres OB, Mayorov AV, Li FY, Antoline JFG, Jacobson AE, Rice KC, Deschamps JR, Beck Z, Alving CR, Matyas GR. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015;26:1041–1053. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Stowe GN, Vendruscolo LF, Edwards S, Schlosburg JE, Misra KK, Schulteis G, Mayorov AV, Zakhari JS, Koob GF, Janda KD. J Med Chem. 2011;54:5195–5204. doi: 10.1021/jm200461m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bremer PT, Janda KD. J Med Chem. 2012;55:10776–10780. doi: 10.1021/jm301262z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vardanyan R, Kumirov VK, Nichol GS, Davis P, Liktor-Busa E, Rankin D, Varga E, Vanderah T, Porreca F, Lai J, Hruby VJ. BMC. 2011;19:6135–6142. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Kunz H, Birnbach S. ACIE. 1986;25:360–362. [Google Scholar]; b) Kunz H, Birnbach S, Wernig P. Carbohydrate Research. 1990;202:207–223. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)84081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kunz H, von dem Bruch K. Methods in Enzymology. 1994;247:3–30. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)47003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bannon AW, Malmberg AB. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2007;Chapter 8(Unit 8):9. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0809s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Klenkar G, Liedberg B. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:1679–1688. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sakai G, Ogata K, Uda T, Miura N, Yamazoe N. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 1998;49:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Runagyuttikarn W, Law MY, Rollins DE, Moody DE. J An Toxicol. 1990;14:160–164. doi: 10.1093/jat/14.3.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Makowski GS, Richter JJ, Moore RE, Eisma R, Ostheimer D, Onoroski M, Wu AHB. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1995;25:169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) German CL, Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR. Life Sciences. 2014;97:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Henderson J. Forensic Sci. 1988;33:569–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.