Abstract

Objectives. To examine changes in active life expectancy in the United States over 30 years for older men and women (aged ≥ 65 years).

Methods. We used the 1982 and 2004 National Long Term Care Survey and the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study to estimate age-specific mortality and disability rates, the overall chances of survival and of surviving without disability, and years of active life for men and women.

Results. For older men, longevity has increased, disability has been postponed to older ages, disability prevalence has fallen, and the percentage of remaining life spent active has increased. However, for older women, small longevity increases have been accompanied by even smaller postponements in disability, a reversal of a downward trend in moderate disability, and stagnation of active life as a percentage of life expectancy. As a consequence, older women no longer live more active years than men, despite their longer lives.

Conclusions. Neither a compression nor expansion of late-life disability is inevitable. Public health measures directed at older women to postpone disability may be needed to offset impending long-term care pressures related to population aging.

As the US population has aged, concerns about meeting the nation’s late-life disability and care needs have grown.1 Questions about just how pressing needs will be are magnified by statistics about the large baby boom generation, whose long-term care demands are expected to peak around 2030. In that year, 1 in 5 persons in the United States will be aged 65 years or older, compared with 15% in 2015.2

The future long-term care needs of older men and women will depend in part on longevity increases and on whether they are accompanied by an expansion or compression of end-of-life disability and dependency. More than 3 decades ago, competing theories about the implications of population aging for late-life functioning were proposed.3–5 The first posited that medical advances would necessarily lead to increased survival of persons with chronic morbidity and would expand the proportion of life spent in ill health.3 Another suggested that health promotion and disease prevention would increase the age at onset of disease and disability and yield a shorter period of infirmity before death.4 A third perspective recognized that mortality and disability were dynamic interrelated processes and that population-level changes in disability would depend on the particular combination of factors driving mortality decline (e.g., postponement of onset and reductions in severity and progression of chronic disease).5 Implicit in the latter theory is the possibility that different subgroups, such as men and women, might experience different outcomes, and that episodes of disability that were longer on average but also milder could materialize.

Implications of mortality shifts for disability in later life are challenging to assess. Because population-level changes in health and longevity tend to occur slowly, long-term data are ideal for investigating such shifts, yet population-based measures of disability were not consistently collected in the United States until the early 1980s. Nevertheless, several studies have pointed to a pattern consistent with an overall compression of morbidity through the 1980s and 1990s.6–10 More recent analysis focusing on the 2000s raises the question of whether such a compression has continued. For example, small increases in remaining years free from activity limitations were found for men but not women at age 65 years for the 1999-to-2008 period,11 and declines in years remaining free from mobility impairments were found for both men and women for a similar time period.12

Despite well-established evidence that women are more likely than men to have activity restrictions in later life,13,14 little attention has focused on gender differences in long-term trends. Whether women’s disadvantage has grown with respect to late-life disability, and, if so, why, are important questions, as women make up a substantial share—57%—of the population aged 65 years or older in the United States and an even larger share—68%—of those receiving assistance with daily tasks.1

Several factors have changed in recent years that suggest that men and women may be experiencing different long-term patterns. First, demographers have long recognized that women in the United States outlive men, as they do in most countries,15 yet men in the United States have gained substantial ground in life expectancy relative to women over the past few decades as cardiovascular-related deaths have declined.16 Some of this narrowing has been attributed to shifts in smoking histories of US women, which now more closely mirror those of men.17 Second, causes of death have also shifted; US women are now as likely as men to die from chronic respiratory disease and 30% more likely than men to die from Alzheimer’s disease.18,19 Third, a substantial decline in late-life disability prevalence has been documented for this country for the 1980s and 1990s,20–23 but a recent flattening suggestive of an impending reversal has been identified, along with increased prevalence relative to earlier decades among those approaching later life.24,25 Others have noted recent increases in more moderate disability among older adults.26

Our interest is in highlighting gender differences in mortality and disability linkages in the United States since the early 1980s. We examined changes over 3 decades in the chances of survival beyond age 65 years overall and without disability, mortality rates by age and disability status, the prevalence of disability, and the number and percentage of remaining years expected to be lived free from disability. For the latter, we considered both severe and more moderate forms of disability.

METHODS

In this study, we drew on cross-sections from 2 longitudinal data sources that were designed to track long-term disability trends in the United States: the 1982 and 2004 National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS) screener samples and the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). Both the NLTCS and the NHATS samples are representative of Medicare enrollees aged 65 years or older drawn from the Medicare Enrollment File. Although NHATS developed and administered an innovative disability protocol, the initial 2011 round also reproduced the disability screening questions used in the NLTCS to support comparisons with earlier decades.

The NLTCS was first conducted in 1982, and its sample was replenished to achieve cross-sectional representation in each of 5 subsequent waves through 2004, its final year.27 The NLTCS administered a brief disability screening interview to all sample members in 1982 and repeated the screener for all sample members (except those known to be living in institutions) in 2004. Initial screening attempts were conducted by telephone; nonrespondents and those without telephones had screening attempted in person. The screening data are available for 19 650 respondents in 1982 and 15 993 in 2004. Response rates to the screener interview were 87.3% and 80.6% in 1982 and 2004, respectively.

The first round of NHATS was conducted in 2011 with 8245 respondents drawn from the Medicare enrollment file. This baseline round had a response rate of 70.9%.28 Like the NLTCS, the NHATS sample represents the population aged 65 years or older in all settings, including institutions. The NHATS interviews were conducted in person, and 8077 respondents either completed the sample person interview or were living in a nursing home and had a facility questionnaire completed by facility staff.

Measures

Activity limitations were measured with the same questions in both studies. Respondents were told,

The next few questions are about your ability to do everyday activities without help. By help, I mean either the help of another person, including the people who live with you, or the help of special equipment.

They were then asked if they had any problem with eating without the help of another person or special equipment, getting in or out of bed without help, getting in or out of chairs without help, walking around inside without help, going outside without the help of another person or special equipment, dressing without help, bathing without help, and getting to the bathroom or using the toilet. Next they were asked if they were able to prepare meals without help, do laundry without help, do light housework such as washing dishes, shop for groceries without help, manage money (such as keeping track of bills and handling cash), take medicine without help, and make telephone calls without help. For each negative response, a follow-up question asked, “Does a disability or a health problem keep you from [activity]?”

Respondents were considered to have a limitation if they reported a problem with (or that they could not or did not do) any of the mobility or self-care activities or were unable to carry out a domestic activity because of a disability or health problem. In all 3 years, we assumed that respondents living in nursing facilities had a limitation. For analysis of active life expectancy, we further distinguished between having severe disability, which we defined as a problem carrying out 3 or more personal care activities without help or living in a nursing facility, and moderate disability, defined as a problem with 1 or 2 personal care activities or being unable to carry out only household activities.

The NLTCS recorded deaths through 1984, from the 1984 follow-up to the 1982 survey and linkages to Medicare records, yielding a 2-year mortality rate. Similarly, NHATS recorded mortality during follow-up attempts in 2012 and 2013, also yielding a 2-year mortality rate. We benchmarked the NLTCS and NHATS mortality rates to 2-year rates estimated from the National Center for Health Statistics for 1982 to 1983 and for 2011 to 2012 and found very close agreement (not shown). Therefore, we approximated 1-year mortality rates in 1982 and 2011 with one half the 2-year rate calculated from each survey.

Statistical Methods

We calculated survival curves by using standard abridged life table methods.29 Using 1-year mortality rates calculated from each survey, we calculated the conditional probability of dying in each 5-year age interval (with a final interval of 10 years). We applied these probabilities to a hypothetical cohort of 100 000 to calculate the corresponding number and percentage expected to survive to the beginning of each age category. We then calculated life expectancy at age x for men and women in 1982 and in 2011 by dividing the total person-years lived from age x by the number surviving to age x.

We apportioned life expectancy into years to be lived with and without disability by using Sullivan’s methodology,30–32 which divides person-years expected to be lived in each age group (nLx) according to the percentage in each age group with (πx) and without (1-πx) disability. We calculated the number surviving to each age x without disability by transforming person-years lived without disability according to

where ndx is the number of deaths expected in the interval among those without disability and n is the width of the interval—in this case, 5.

We calculated disability-free life expectancy for men and women in 1982 and in 2011 for each age interval n by dividing the total years to be lived without disability from age x forward to the final category (w) by the number surviving to age x (lx). The variance of this estimate is

|

where Vx is the survey-adjusted variance of πx. We calculated test statistics for differences in disability-free life expectancy between men and women in 1982 and in 2011 and between 1982 and 2011 for men and for women.32 We repeated the active life expectancy analysis by using the previously described measure of severe disability.

We decomposed the change in active life expectancy for men and women into 2 components: (1) changes attributable to the number of person-years lived (i.e., mortality changes) and (2) changes attributable to the risks of not having disability. We calculated the former by multiplying, for each age group, the average proportion living without disability in 1982 and 2011 by the change in person-years lived in that age group between 1982 and 2011; the latter is the product of the average number of person-years lived in the age group in 1982 and 2011 and the change between 1982 and 2011 in the proportion in that age group living without disability.33

We also report stratified 1982 and 2011 1-year mortality estimates by 5-year age group, gender, and whether an activity limitation was reported. For disability prevalence estimates in all 3 years, we standardized estimates in each year to the 2010 age distribution of the male population. We calculated age-adjusted estimates of having any disability, limitations in each individual activity, and severe and moderate disability.

We calculated all estimates by using survey weights that take into account differential probabilities of selection and differential nonresponse.34,35 Reports of statistical significance are based on standard errors that reflect the complex designs of the surveys.

RESULTS

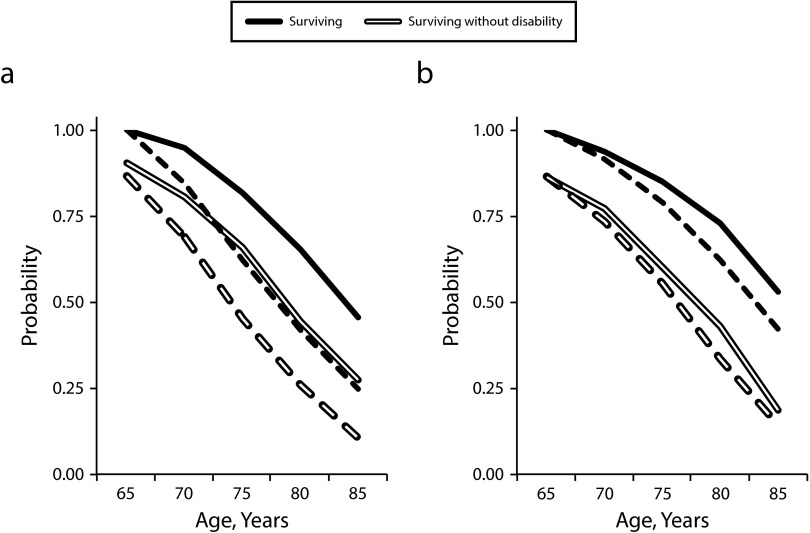

Between 1982 and 2011, the chances beyond age 65 years of overall survival and survival without disability have increased, but different patterns of change are evident for men and women (Figure 1). For men, the 2 curves have shifted about equally toward older ages, with a notable flattening at the younger ages. For women, the shifts toward later ages have been much smaller than for men, concentrated above age 70 years, and greater for overall survival than for survival without disability.

FIGURE 1—

Overall Probability of Surviving and Probability of Surviving Without Disability Conditional on Surviving to Age 65 Years Among (a) Men and (b) Women: United States, 1982 (Broken Line) and 2011 (Unbroken Line)

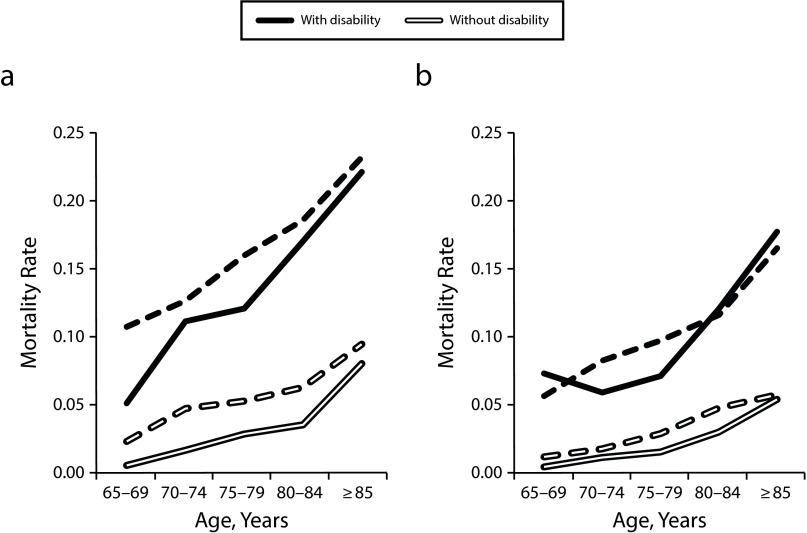

Underlying mortality risks have shifted for both men and women according to age and disability status (Figure 2). Although women without disability had the lowest mortality rates in 1982, they had experienced only small absolute improvements in mortality by 2011. By contrast, substantial improvements occurred for men both with and without disability (for all but the oldest age group) and for women in their late 70s living with disability.

FIGURE 2—

One-Year Mortality Rates by Disability Status and Age Among (a) Men and (b) Women: United States, 1982 (Broken Line) and 2011 (Unbroken Line)

During the same period, disability prevalence declined for women and then began to reverse course (Table 1). When we controlled for differences in age structure over time and between men and women, the percentage of older men living with a disability fell from 1982 to 2004 by nearly 7 percentage points and then rose an insignificant amount from 2004 to 2011 (P = .13 for difference from 2004). By contrast, for women, the prevalence fell from 1982 to 2004 by 5.6 percentage points and then rose from 2004 to 2011 by 4 percentage points (P < .01 for difference from 2004). As a consequence, the age-adjusted gap between men and women has nearly doubled from less than 4 percentage points in 1982 to more than 7 percentage points in 2011.

TABLE 1—

Age-Adjusted Percentages of US Men and Women Aged 65 Years and Older With Specific Types of Activity Limitations: 1982, 2004, and 2011

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||

| Variables | 1982, % | 2004, % | 2011, % | P, 2011 vs 1982 | P, 2011 vs 2004 | 1982, % | 2004, % | 2011, % | P, 2011 vs 1982 | P, 2011 vs 2004 |

| Limitation severity | ||||||||||

| Any limitation | 22.3 | 15.5 | 16.6 | < .01 | .13 | 25.8 | 20.2 | 24.2 | .04 | < .01 |

| Moderate: limited in only household activities or 1 or 2 personal care activities | 11.6 | 8.5 | 9.3 | < .01 | .17 | 12.6 | 10.4 | 14.0 | .02 | < .01 |

| Severe: limited in 3 or more personal care activities or in a nursing facility | 10.7 | 7.0 | 7.3 | < .01 | .55 | 13.2 | 9.8 | 10.2 | < .01 | .45 |

| Personal care activities: any problem with (or cannot do or does not do) | ||||||||||

| Eating without the help of another person or special equipment | 6.3 | 3.7 | 3.9 | < .01 | .58 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 4.7 | < .01 | .31 |

| Getting in or out of bed without help | 8.3 | 5.1 | 5.8 | < .01 | .14 | 10.4 | 7.2 | 8.1 | < .01 | .09 |

| Getting in or out of chairs without help | 9.0 | 5.9 | 6.4 | < .01 | .34 | 11.1 | 8.2 | 9.0 | < .01 | .12 |

| Walking around inside without help | 12.1 | 8.4 | 7.0 | < .01 | .03 | 14.5 | 11.2 | 10.0 | < .01 | .02 |

| Going outside without the help of another person or special equipment | 15.0 | 10.8 | 9.4 | < .01 | .03 | 19.5 | 15.1 | 16.1 | < .01 | .11 |

| Dressing without help | 9.0 | 5.7 | 6.8 | < .01 | .05 | 10.3 | 7.2 | 8.6 | < .01 | .01 |

| Bathing without help | 10.8 | 6.7 | 7.4 | < .01 | .19 | 13.3 | 9.5 | 9.5 | < .01 | .99 |

| Getting to the bathroom or using the toilet | 7.8 | 4.9 | 5.0 | < .01 | .87 | 10.0 | 7.1 | 6.9 | < .01 | .77 |

| Household activities: because of a disability or health problem unable to | ||||||||||

| Prepare meals without help | 12.2 | 7.4 | 7.2 | < .01 | .68 | 12.8 | 9.3 | 9.8 | < .01 | .32 |

| Do laundry without help | 14.2 | 8.0 | 8.0 | < .01 | .99 | 15.4 | 10.2 | 11.4 | < .01 | .04 |

| Do light housework such as washing dishes | 11.7 | 7.2 | 7.0 | < .01 | .79 | 11.6 | 8.6 | 8.3 | < .01 | .64 |

| Shop for groceries without help | 15.9 | 9.9 | 9.5 | < .01 | .47 | 20.5 | 14.2 | 15.6 | < .01 | .04 |

| Manage money, such as keeping track of bills and handling cash | 10.5 | 6.9 | 7.8 | < .01 | .14 | 11.7 | 8.4 | 9.6 | < .01 | .01 |

| Take medicine without help | 9.1 | 6.3 | 7.0 | < .01 | .20 | 9.8 | 7.4 | 8.1 | < .01 | .09 |

| Make telephone calls without help | 11.4 | 6.0 | 5.0 | < .01 | .02 | 10.4 | 6.5 | 6.1 | < .01 | .37 |

Note. Estimates adjusted to the age distribution for men based on the 2010 US Census. Individuals in nursing facilities were assumed to have all limitations.

The growing gap is attributable to increases for women in less-severe forms of disability, notably limitations in household activities. A greater percentage of women in 2011 than in 2004 reported being unable, because of their health or disability, to shop, manage money, or do laundry without help.

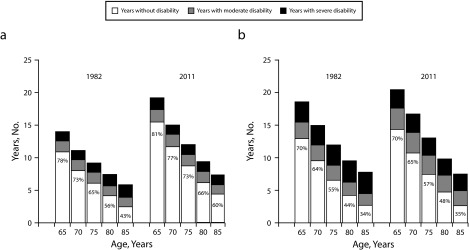

Although expected years lived with disability at age 65 years did not change substantially for men and women, life expectancy and active life expectancy patterns shifted differentially for the 2 groups (Figure 3). Over the full 30-year period, men’s active life expectancy at age 65 years increased by 4.5 years (from just under 11 years in 1982 to more than 15 years in 2011); women’s active life expectancy increased by only 1.4 years (from just under 13 years in 1982 to more than 14 years in 2011). For men and women, at age 65 years, the number of years expected to be lived with severe disability remained stable between 1982 and 2011 at 1.5 years for men (P = .24 for difference between 1982 and 2011) and at about 3 years for women (P = .70).

FIGURE 3—

Expected Number of Remaining Years Lived With Severe and Moderate Disability and Without Disability and Percentage of Remaining Years Expected to be Lived Without Disability Among (a) Men and (b) Women: United States, 1982 and 2011

As a consequence, the advantage over men in disability-free life expectancy that women experienced at age 65 years in 1982 was no longer present in 2011. Women aged 85 years and older, whose disability-free life expectancy was on par with men in 1982 (2.5 years for both groups), were expected to live without disability for fewer years than men in 2011 (2.6 vs 4.4; P < .01). For men and women, more than three fourths of the growth in disability-free years is attributable to declines in mortality rates rather than changes in disability prevalence.

The increasing gap between men and women is also evident from an examination of the percentage of years expected to be lived without disability. For a 65-year-old man, this figure increased—from 78% in 1982 to 81% in 2011—but it remained stable for women at 70%. At older ages, the improvement for men is even more marked: 43% of remaining years at age 85 years were expected to be active in 1982 compared with 60% in 2011. For women, the proportion of remaining years at age 85 years expected to be active was stable at about 35%.

DISCUSSION

Our evidence suggests that neither a compression nor expansion of disability is an inevitable result of population aging. Instead, mortality and disability have changed in different ways for men and women in the United States over the past 30 years. For men, longevity has increased and disability has been postponed to older ages, disability prevalence has fallen, and the percentage of remaining life spent active has increased, especially at much older ages. For women, small longevity increases have been accompanied by even smaller postponements in disability onset, a reversal of the downward trend in moderate disability prevalence, and overall stagnation of active life as a percentage of life expectancy. As a consequence, the gap between men and women in disability prevalence has increased, and women have lost ground relative to men in both life expectancy and active life expectancy.

Our findings extend earlier studies of active life expectancy by focusing on gender differences over 3 decades. Largely because of data constraints, with few exeptions,10 previous studies have focused on somewhat narrower (generally 10- or 20-year) time periods.6–9,11,12 On balance, our findings are consistent with these studies, which have found compression of morbidity at age 65 years during the 1980s and 1990s and some evidence of expansion for the first decade of the 21st century. By focusing on gender differences we extend this literature by demonstrating that despite longer lives, older women no longer live a greater number of active years than men. We further demonstrate that the change from the early 1980s has been driven largely by changes in mortality rates—which have fallen among older women living with disability—rather than changes in disability prevalence.

An encouraging finding also emerged: we found no evidence that the average duration of severe disability at the end of life has increased among either men or women during this 30-year period. Given other research that suggests that the majority of individuals with severe limitations are low-income and receive paid care, and more than 40% live in residential care settings (i.e., nursing homes, assisted living, or other supportive-care settings),1 the lack of such a trend undoubtedly has beneficial implications for publicly financed long-term care. Nevertheless, close monitoring of this group is needed between now and 2030 when the baby boom generation’s long-term care demands are expected to peak.

Placing these US trends in context of other developed countries is challenging because long-term disability data of the kind presented here are not generally available over 3 decades. Nevertheless, a few countries have identified worsening health expectancies among very old women over somewhat shorter time frames.36,37 Moreover, similarities exist between gender patterns found in 2011 for the United States and for 11 of 33 European nations, where older women were expected to live fewer years without limitations than men, despite their longer lives.38 More research is needed to understand why such patterns have emerged in particular countries, including the United States.

Limitations

Our analysis has several limitations. First, because we had only 3 cross-sectional sets of measures, we were unable to explore the role of disability onset and recovery in changes in active life expectancy or pinpoint the turning point for moderate disability prevalence for women. However, in this analysis, we found that shifts in mortality, rather than shifts in disability, were more important in accounting for changes in active life expectancy, and other studies have pointed to the early 2000s as the likely beginning of the emergence of increased prevalence in moderate disability.26

Second, although we focused on a widely used measure of disability that is highly relevant for long-term care planning purposes—limitations in self-care, mobility, and household activities—our findings are limited to active life expectancy and do not generalize to broader measures of healthy life, which have improved over the past few decades.39

Third, there are measurement-related issues that, although unlikely to account for findings, we could not fully control. For instance, a large share of the NLTCS interviews was conducted over the telephone whereas NHATS was conducted in person. A review of experimental evidence evaluating the influence of mode on reports of disability suggests, however, that substantial effects are unlikely.40,41 Response rates also differed, which could introduce bias if the chances of responding changed differentially over time by disability status; however, the use of nonresponse adjusted weights reduces this concern.34,35 We also explored whether differences in placement of the disability questions in NHATS (near the end) and in the NLTCS (as a free-standing initial interview) could distort findings. If placement at the end led to inflated affirmative reports, we would expect to see less severe disability (e.g., fewer reports of assistance) among those meeting the screener criteria in 2011 compared with earlier years. On the basis of responses to more detailed questions about help received with activities available in both studies, we found no such pattern. Hence, we conclude that placement is unlikely to be substantially distorting results.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our findings have implications for public health officials interested in improving functioning of the older population in the United States. Our analysis suggests that greater focus on quality rather than quantity of life, emphasizing risk factors more commonly found among women, may be an effective strategy for extending active life. Women are more likely than men to develop a number of debilitating conditions including arthritis, depressive symptoms, fall-related fractures, and Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias that have implications for active life.42–47 Older women are also more likely to be sedentary and obese,43 and their smoking behaviors appear more detrimental than for men.48 Finally, older women continue to have fewer economic resources than men with which to accommodate declines in functioning in ways that stave off disability.49,50 Enhanced attention to these and other preventable causes of limitations among older women could extend active life and help offset impending long-term care pressures related to population aging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the National Institute on Aging of the US National Institutes of Health grant U01 AG032947.

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the first annual meeting of the Network on Life Course Health Dynamics and Disparities, May 4, 2015, San Diego, CA, and at the annual Disability TRENDS Network meeting, May 22, 2015, Ann Arbor, MI, with funding from the National Institute on Aging of the US National Institutes of Health grants R24 AG045061 and P30 AG012846.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors. The views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not represent those of their employers or funding agency.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional review board approval was not required for this study because data were obtained from secondary sources.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and care needs among older Americans. Milbank Q. 2014;92(3):509–541. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colby SL, Ortman JM. The Baby Boom Cohort in the United States: 2012 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. pp. 25–1141. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruenberg EM. The failures of success. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1977;55(1):3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fries JF. Aging, natural death and the compression of morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(3):130–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007173030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manton KG. Changing concepts of morbidity and mortality in the elderly population. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1982;60(2):183–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crimmins EM, Saito Y, Ingegneri D. Trends in disability-free life expectancy in the United States, 1970–1990. Popul Dev Rev. 1997;23(3):555–572. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Hagedorn A, Saito Y, Brouard N. Change in disability-free life expectancy for Americans 70-years-old and older. Demography. 2009;46(3):627–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai L, Lubitz J. Was there compression of disability for older Americans from 1992 to 2003? Demography. 2007;44(3):479–495. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crimmins EM, Saito Y. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the United States, 1970–1990: gender, racial, and educational differences. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(11):1629–1641. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manton KG, Gu X, Lamb V. Long-term trends in life expectancy and active life expectancy in the United States. Popul Dev Rev. 2006;32:81–105. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molla MT Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Expected years of life free of chronic condition–induced activity limitations—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62(suppl 3):87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crimmins EM, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(1):75–86. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nathanson CA. Illness and the feminine role: a theoretical review. Soc Sci Med. 1975;9(2):57–62. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(75)90094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verbrugge LM. Gender and health: an update on hypotheses and evidence. J Health Soc Behav. 1985;26(3):156–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beltrán-Sánchez H, Finch CE, Crimmins EM. Twentieth century surge of excess adult male mortality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(29):8993–8998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421942112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61(4):1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preston SH, Wang H. Sex mortality differences in the United States: the role of cohort smoking patterns. Demography. 2006;43(4):631–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aryal S, Diaz-Guzman E, Mannino DM. Influence of sex on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk and treatment outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1145–1154. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S54476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tejada-Vera B. Mortality from Alzheimer’s disease in the United States: data for 2000 and 2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;116:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manton KG, Gu X, Lamb VL. Changes in chronic disability from 1982 to 2004/2005 as measured by long-term changes in function and health in the U.S. elderly population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(48):18374–18379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608483103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spillman BC. Changes in elderly disability rates and the implications for health care utilization and cost. Milbank Q. 2004;82(1):157–194. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf DA, Hunt K, Knickman J. Perspectives on the recent decline in disability at older ages. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):365–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedman VA, Crimmins EM, Schoeni RF et al. Resolving inconsistencies in trends in old-age disability: report from a technical working group. Demography. 2004;41(3):417–441. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Andreski P et al. Trends in late-life activity limitations: an update from five national surveys. Demography. 2013;50(2):661–671. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin LG, Schoeni RF, Andreski P. Trends in health of older adults in the United States: past, present, future. Demography. 2010;47(suppl):S17–S40. doi: 10.1353/dem.2010.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin SF, Beck AN, Finch BK, Hummer RA, Master RK. Trends in US older adult disability: exploring age, period, and cohort effects. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2157–2163. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manton KG. National Long-Term Care Survey: 1982, 1984, 1989, 1994, 1999, and 2004. ICPSR09681-v5. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2010.

- 28.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. National Health and Aging Trends Study Round 1 User Guide: Final Release. 2012. Available at: http://nhats.org/scripts/documents/NHATS_Round_1_User_Guide_Final_Release.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2015.

- 29.Arias E. United States life tables, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(7):1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan DF. A single index of mortality and morbidity. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86(4):347–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathers CD, Robine JM. How good is Sullivan’s method for monitoring changes in population health expectancies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51(1):80–86. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagger C, Cox B, Le Roy S. Health Expectancy Calculation by the Sullivan Method. 3rd ed. Montpellier, France: 2006. European Health Expectancy Monitoring Unit. European Health Expectancy Monitoring Unit Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nusselder WJ, Looman CWN. Decomposition of differences in health expectancy by cause. Demography. 2004;41(2):315–334. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Census Bureau. Weighting specifications for the Long Term Care Survey. Washington DC: US Census Bureau; 1982. Available at: http://www.nltcs.aas.duke.edu/pdf/82_CrossSectionalWeights.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2015.

- 35.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Spillman B, Kasper JD. National Health and Aging Trends Study development of round 1 survey weights. 2012. NHATS technical paper 2. Available at: http://nhats.org/scripts/documents/NHATS_Round1_WeightingDescription_Nov2012.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2015.

- 36.Yong V, Saito Y. Trends in healthy life expectancy in Japan: 1986–2004. Demogr Res. 2009;20:467–494. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Oyen H, Cox B, Demarest S, Deboosere P, Lorant V. Trends in health expectancy indicators in the older adult population in Belgium between 1997 and 2004. Eur J Ageing. 2008;5(2):137–146. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eurostat. Healthy life years. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/health/health-status-determinants/data/database. Accessed May 28, 2015.

- 39.Stewart ST, Cutler D, Rosen A. US trends in quality-adjusted life expectancy from 1987 to 2008: combining national surveys to more broadly track the health of the nation. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):e78–e87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. Improving the measurement of late-life disability in population surveys: beyond ADLs and IADLs. Summary of a workshop. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Leeuw E. To mix or not to mix data collection modes in surveys. J Off Stat. 2005;21:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laditka SB, Laditka JN. Recent perspectives on active life expectancy for older women. J Women Aging. 2002;14(1-2):163–184. doi: 10.1300/J074v14n01_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leveille SG, Resnick H, Balfour J. Gender differences in disability: evidence and underlying reasons. Aging. 2000;12(2):106–112. doi: 10.1007/BF03339897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Case A, Paxson C. Sex differences in morbidity and mortality. Demography. 2005;42(2):189–214. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Solé-Auró A. Gender differences in health: results from SHARE, ELSA and HRS. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(1):81–91. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr P, Evans D. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 Census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–1783. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevens JA, Sogolow E. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Inj Prev. 2005;11(2):115–119. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.005835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sloan F, Ostermann J, Picone G, Conover C, Taylor D. The Price of Smoking. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Spillman BC et al. Behavioral adaptation and late-life disability: a new spectrum for assessing public health impacts. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e88–e94. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]