Summary

Hexanucleotide expansions in C9ORF72 are the most frequent genetic cause of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Disease mechanisms were evaluated in mice expressing C9ORF72 RNAs with up to 450 GGGGCC repeats or with one or both C9orf72 alleles inactivated. Chronic 50% reduction of C9ORF72 did not provoke disease, while its absence produced splenomegaly, enlarged lymph nodes, and mild social interaction deficits, but no motor dysfunction. Hexanucleotide expansions caused age-, repeat length- and expression level-dependent accumulation of RNA foci and dipeptide-repeat proteins synthesized by AUG-independent translation, accompanied by loss of hippocampal neurons, increased anxiety, and impaired cognitive function. Single dose injection of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) that target repeat-containing RNAs but preserve levels of mRNAs encoding C9ORF72 produced sustained reductions in RNA foci and dipeptide-repeat proteins, and ameliorated behavioral deficits. These efforts identify gain-of-toxicity as a central disease mechanism caused by repeat-expanded C9ORF72 and establish the feasibility of ASO-mediated therapy.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are two devastating adult-onset neurodegenerative diseases with distinct clinical features but common pathological features and genetic causes (Ling et al., 2013). Hexanucleotide GGGGCC repeat expansions in a noncoding region of the C9ORF72 gene are the most common inherited cause of ALS and FTD (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011). Proposed mechanisms by which C9ORF72 repeat expansions cause disease (referred to as C9ALS/FTD) include loss of C9ORF72 protein function and gain of toxicity (Gendron et al., 2014; Ling et al., 2013).

A reduction in C9ORF72 function (i.e., haploinsufficiency) is supported by decreased expression of C9ORF72 mRNAs in patient tissues resulting from DNA and histone hypermethylation with partial silencing of the repeat-containing allele (Belzil et al., 2013; DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Gijselinck et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014; Xi et al., 2015; Xi et al., 2013). RNA gain of toxicity has been proposed to arise from folding of repeat-containing RNAs into stable structures that sequester RNA-binding proteins to nuclear RNA foci, a mechanism originally established for myotonic dystrophy (reviewed by (Wojciechowska and Krzyzosiak, 2011)). Indeed, foci containing sense GGGGCC or antisense GGCCCC repeat RNA are present in tissues from C9ALS/FTD patients (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Gendron et al., 2013; Lagier-Tourenne et al., 2013; Mizielinska et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2013a; Zu et al., 2013). Several RNA-binding proteins appear enriched in sense RNA foci (Cooper-Knock et al., 2014; Donnelly et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2013b; Sareen et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2013), but evidence supporting a loss of function of these proteins is lacking.

Another proposed disease mechanism from C9ORF72 repeat expansions is the production of aberrant dipeptide-repeat (DPR) proteins through repeat-associated non-AUG dependent (RAN) translation, a phenomenon discovered in spinocerebellar ataxia type 8 and myotonic dystrophy (Zu et al., 2011). In C9ALS/FTD patients, five DPR proteins – poly(GA), poly(GR), poly(GP), poly(PA) and poly(PR) – are produced from all reading frames of either sense or antisense repeat-containing RNAs (Ash et al., 2013; Gendron et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2013a; Mori et al., 2013c; Zu et al., 2013). DPR proteins form p62-positive, TDP-43-negative inclusions, with poly(GA), poly(GP) and poly(GR) aggregates being the most abundant (Mackenzie et al., 2014; Mori et al., 2013c). Poly(GP) and poly(GA) can also be detected by immunoassay in patient-derived cultured cells, postmortem tissues and cerebrospinal fluid (Gendron et al., 2015; Su et al., 2014; van Blitterswijk et al., 2015). Overexpressing (Mizielinska et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015) or exogenously exposing (Kwon et al., 2014) cells and other model systems to high levels of arginine-containing DPR proteins induces rapid cell death. Other studies have reported poly(GA) to be particularly prone to aggregation and to confer toxicity (Gendron et al., 2015; May et al., 2014; Schludi et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). Lastly, a recent flurry of studies found that nucleocytoplasmic transport is impaired in C9ALS/FTD (Boeynaems et al., 2016; Freibaum et al., 2015; Jovicic et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016), although the exact roles of RNA foci and/or DPR proteins in this pathway are not yet resolved. Indeed, divergent outcomes were reported regarding the toxicity of repeat-containing RNAs or DPR proteins in cell culture (Devlin et al., 2015; Kwon et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2013; May et al., 2014; Rossi et al., 2015; Schludi et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Zu et al., 2013), flies (Freibaum et al., 2015; Mizielinska et al., 2014; Tran et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015), yeast (Jovicic et al., 2015) and mice (Chew et al., 2015; Hukema et al., 2014; O’Rourke et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016).

By production and analysis of mice in which one or both C9orf72 alleles were inactivated, and multiple transgenic mouse lines expressing up to 450 C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeats, we tested disease mechanism(s) associated with C9ALS/FTD. Herein we show a repeat length-dependent gain of toxicity, while chronic reduction of C9ORF72 does not produce nervous system disease. Single dose injection of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) that selectively target repeat-containing RNAs cause a rapid reduction in RNA foci and DPR proteins, while maintaining overall levels of C9ORF72-encoding mRNAs and producing a sustained alleviation of behavioral deficits.

Results

Reduction in C9ORF72 is well tolerated but splenomegaly and enlarged lymph nodes develop in its absence

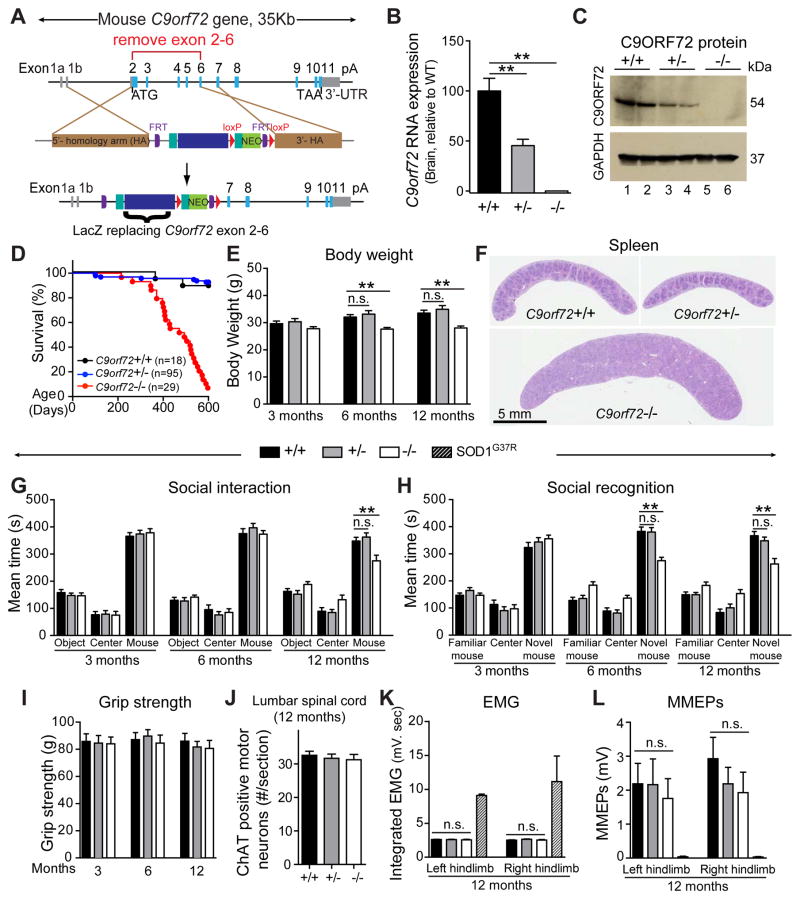

To determine the consequence of loss of C9ORF72 function in vivo, mice were generated in which a LacZ reporter replaced exons 2 to 6 of the endogenous C9orf72 gene (Figure 1A). As expected, total C9orf72 RNAs and the full-length 54 kD C9ORF72 protein were reduced to 50% in brains of heterozygous C9orf72+/− mice and were completely absent in homozygous C9orf72−/− mice (Figure 1B,C). A β-galactosidase activity assay, used to assess endogenous C9orf72 gene expression throughout the central nervous system (CNS), revealed broad expression of C9orf72 not only in neurons of the gray matter as previously reported (Suzuki et al., 2013), but also in glial cells of white matter in various CNS regions, including the cerebellum and spinal cord (Figure S1A,B). Further evidence confirming substantial expression of the C9of72 gene in glial cells was obtained using high-throughput sequencing of translated RNAs purified from BacTRAP transgenic mice that express EGFP-tagged ribosomal protein L10a in defined cell populations (Heiman et al., 2008). C9orf72 RNAs were identified in all three cell types tested, with relative abundances of 2.5:1:1 in motor neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, respectively (Figure S1C). No overt neuropathology developed in C9orf72+/− or C9orf72−/− mice and no increase in GFAP-positive astrocytes or IBA-1-positive microglia occurred in brain and spinal cord (Figure S1D,E).

Figure 1. Reduction of C9ORF72 is well tolerated, but complete loss of C9ORF72 induces premature death and splenomegaly.

(A) Targeting strategy to generate C9orf72 null mice with exons 2–6 replaced with β-galactosidase and neomycin (Neo) genes. Schematic shows (upper panel) the genomic region, (middle panel) targeting construct, and (lower panel) final targeted C9orf72 gene. Filled boxes correspond to exons. Open box represents the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR). (B) Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of mouse C9orf72 RNAs in brains of C9orf72+/+, C9orf72+/− and C9orf72−/− mice (n=6 per group). (C) Immunoblot demonstrating the levels of the 54 kD mouse C9ORF72 protein. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D) Survival curve up to 600 days. (E) Body weights at 3, 6 and 12 months of age (n=25 per genotype). (F) Spleen sizes at 12 months of age. (G–I) Behavioral performance measured at 3, 6 and 12 months of age (n=25 animals per group). (G) Social interactions measured by the mean time spent with an object, in the center, or with a mouse. (H) Social recognition measured by the mean time spent with a familiar mouse, in the center, or with a novel mouse. (I) Hindlimb grip strength. (J) Average number of ChAT-positive neurons per section in the anterior horn of lumbar spinal cord in 12 month old mice (n=4–5 per group). (K) Resting electromyographic (EMG) recordings, and (L) myogenic motor evoked potentials (MMEPs) in 12 month old C9orf72 mice (n=5 per genotype) or in end-stage transgenic mice expressing mutant SOD1G37R (crosshatched bars, n=2). Error bars represent s.e.m in biological replicates, n.s. not significant, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 using one-way ANOVA.

(See also Figure S1 and S2).

The reduction in C9ORF72 to 50% of its normal level, as reported in C9ALS/FTD patients, was well tolerated with C9orf72+/− mice surviving into adulthood with a normal body weight and no signs of disease (Figure 1D–F). In contrast, although C9orf72−/− mice were born in the expected Mendelian ratio with no change in survival through 11 months of age, only 7% of mice survived to 20 months of age (Figure 1D). C9orf72 null mice showed reduced body weight (Figure 1E), splenomegaly (Figure 1F), and enlarged cervical lymph nodes (Figure S1F) by 12 months of age. The spleen size was comparable in C9orf72+/− mice (80.33±0.88mg, n=3, mean±s.e.m) versus wild type littermates (80±0.41mg, n=4) at 18 months of age. Staining of CD3-positive T lymphocytes and CD45R/B220-positive B lymphocytes revealed disrupted architectures of the spleen and cervical lymph nodes in C9orf72−/− mice (Figure S1G,H). Despite the enlarged size, the total number of lymphoid cells was not changed in the spleen, while the number of myeloid cells increased dramatically. Both lymphoid and myeloid cells were increased by more than an order of magnitude in the cervical lymph nodes (Figure S2A). In addition, C9orf72 null mice showed decreased hemoglobin, packed cell volume, decreased percentage of lymphocytes, and increased percentage of neutrophils in blood (Figure S2B).

To determine whether partial or complete loss of C9ORF72 triggered age-dependent cognitive and/or motor deficits, longitudinal assessment of strength, motor coordination, anxiety, sociability and learning functions in cohorts of C9orf72+/+, C9orf72+/− and C9orf72−/− mice was performed. No behavioral abnormalities were observed in C9orf72+/− mice at any of the ages tested (3, 6 and 12 months) (Figures 1G–I and S2C–H). By 12 months of age, C9orf72 null mice developed mild social interaction (Figure 1G) and social recognition (Figure 1H) abnormalities compared with wild type or heterozygous littermates. In addition, 12 month old C9orf72−/− mice developed mild motor deficits on a rotarod assay (Figure S2C) without differences in grip strength, gait or general activity (Figures 1I and S2D,E) or loss of ChAT positive lower motor neurons (Figure 1J). Resting electromyographic (EMG) recordings were also normal in the gastrocnemius muscles of mice lacking C9ORF72, consistent with intact neuromuscular connectivity (Figure 1K). The amplitudes of myogenic motor evoked potentials (MMEPs), a measure of connectivity of the entire neuromuscular unit, are comparable among C9orf72+/−, C9orf72−/− and C9orf72+/+ mice (Figure 1L), in contrast to their almost complete loss in end-stage SOD1G37R mice.

Overall, C9ORF72 reduction alone is not sufficient to cause C9ALS/FTD-associated phenotypes in mice.

BAC C9ORF72 transgenic mouse lines with different repeat sizes and expression levels

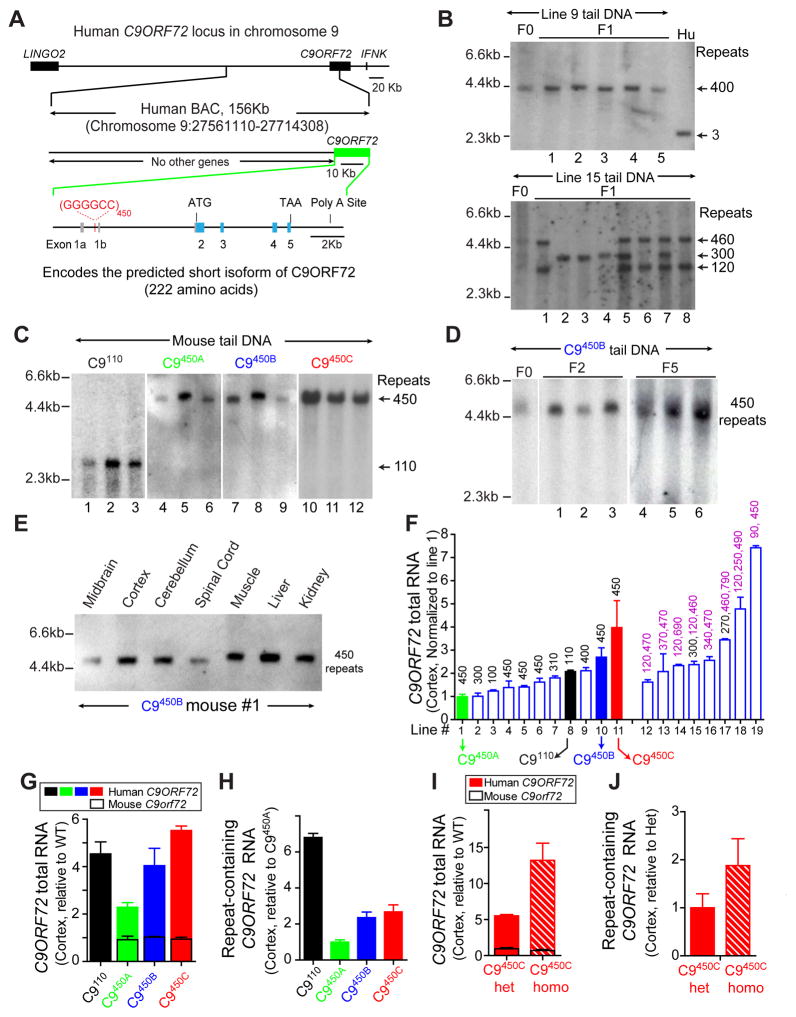

To test a potential gain of toxicity from repeat expansions, transgenic mice were generated that express a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) with the human expanded C9ORF72 gene from a C9ALS patient. The BAC includes 140 kb of sequence 5′ to the C9ORF72 exon 1a (including what is likely to be the complete promoter region) and exons 1 to 5 of the gene. The BAC does not encode the 54 kD C9ORF72 protein (Figure 2A) (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011). The interferon kappa gene, which lies within 23 kb 3′ of C9ORF72 on human chromosome 9, is not present nor is any other known gene besides C9ORF72.

Figure 2. Generation of multiple BAC transgenic mouse lines expressing different levels of a human C9ORF72 transgene with 100 –700 GGGGCC repeats.

(A) Schematic of the human BAC containing 450 GGGGCC repeats in the first intron of a truncated human C9ORF72 gene. The coordinates of the BAC sequence on the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser (Hg19) are indicated. No other gene is on the BAC. (B–D) Genomic DNA blot analysis of tail DNA from (B) founder (F0) and F1 transgenic mice from lines 9 or 15 and DNA from human fibroblasts (Hu) with normal C9ORF72 alleles, (C) twelve different mice of lines 1, 8, 10 and 11 (re-designated C9450A, C9110, C9450B and C9450C, respectively), and (D) mice from F0, F2 and F5 generations in Line C9450B. (E) Repeat lengths determined by genomic DNA blotting using DNA from the CNS and peripheral tissues of a C9450B mouse. (F) Human C9ORF72 RNA in cortex of transgenic mice measured by qRT-PCR, normalized to C9450A mice. Numbers above bars are repeat lengths measured by genomic DNA blots. (G) Expression levels of total (mouse plus human) C9ORF72 RNAs in the cortex of C9110, C9450A, C9450B and C9450C mice normalized to the level of endogenous C9orf72 RNA. (H) Level of repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNA variants in the cortex measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to levels in C9450A mice. (I–J) Levels of (I) total C9ORF72 RNAs (human plus mouse) or (J) repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNA measured by qRT-PCR in the cortex of heterozygous and homozygous C9450C mice, normalized to C9orf72 levels in wild type littermates. Error bars represent s.e.m. from 3–5 biological replicates per group.

(See also Figure S3).

Thirty-two founder mice were generated in a C57BL6/C3H hybrid background and backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice. Founders from eight lines had multiple repeat sizes that either separated in subsequent generations (Figure 2B) or multiple transgene copies with different repeat lengths at the same locus that segregated together (Figure S3A). Eleven lines contained a single repeat size that was stably inherited from F0 to F5 generations in the large majority of mice (Figure 2B–D), albeit analysis of 42 littermates from one line identified 3 repeat contraction events (Figure S3B). At most, modest expansion was found within the CNS or peripheral tissues (Figures 2E and S3C,D), in contrast to humans for whom somatic heterogeneity and repeat instability has been reported, especially within the CNS (van Blitterswijk et al., 2013).

Transgene expression levels were examined in 19 lines carrying between 110 and 790 repeats (Figure 2F). Recognizing that transgenes with multiple repeat sizes would preclude correlation analyses of repeat length and expression-associated toxicity, we selected four lines with defined repeat lengths and/or different transgene expression levels: line 8 with ~110 repeats (hereafter designated C9110) and three lines expressing various levels of RNAs but each containing ~450 repeats (Lines 1, 10 and 11, designated C9450A, C9450B and C9450C, respectively). C9110 and C9450B have comparable levels of transgene expression but different repeat sizes, whereas C9450B has a similar repeat size as C9450A, but higher transgene expression (Figure 2C,F). C9ORF72 transgene-encoded RNAs were three to four times the level of endogenous mouse C9orf72 RNA in lines C9110, C9450B and C9450C, and equal to endogenous C9orf72 in line C9450A (Figure 2G). Endogenous C9orf72 RNAs were unchanged in all lines. Similar to total C9ORF72 RNAs, repeat-containing RNAs (measured by qRT-PCR with variant-specific primers (Figure S3E)) were higher in C9450B mice than C9450A mice. Repeat-containing RNAs were 3 times higher in C9110 than C9450B mice (Figure 2H), despite comparable total C9ORF72 RNA levels (Figure 2G and S3F). Breeding produced homozygous C9450C mice with C9ORF72 expression ~12 times the level of mouse C9orf72 (Figure 2I,J).

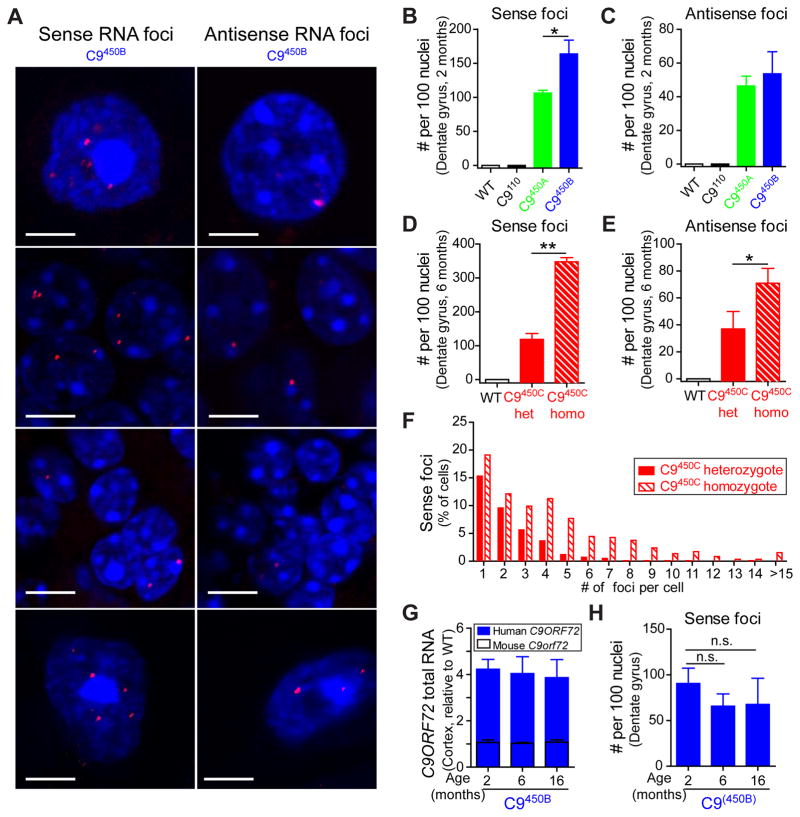

Repeat size- and dose-dependent accumulation of sense and antisense RNA foci

RNAs transcribed from both sense (GGGGCC) and antisense (GGCCCC) strands of C9ORF72 have been reported to accumulate into RNA foci in cultured cells and postmortem tissues from C9ALS/FTD patients (Gendron et al., 2013; Lagier-Tourenne et al., 2013; Mizielinska et al., 2013; Zu et al., 2013). Use of fluorescence in situ hybridization detected sense and antisense foci in all three mouse lines expressing 450 repeats. Foci were found throughout the CNS, including the frontal cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and spinal cord as early as 2 months of age (Figure 3A) and were not observed in wild type mice (Figure S3G). Sense foci were most abundant in the frontal cortex, followed by the hippocampal dentate gyrus, retrosplenial cortex, and molecular layer of the cerebellum (Figure S3H). An unexpected, surprisingly strong influence of repeat length on foci formation was uncovered: whereas mice with 450 repeats developed foci (Figure 3A), neither sense nor antisense foci were detected in any brain region, or at any age, in C9110 mice with 110 repeats (Figure 3B,C). This was despite the fact that transgene expression in C9110 mice was 3.5 times that of endogenous C9orf72 RNAs (7 times the level of RNA from a single endogenous C9orf72 allele) (Figure 2G) and that levels of repeat-containing RNAs in C9110 mice were 3 and 6 times higher than in C9450B and C9450A mice, respectively (Figure 2H).

Figure 3. Repeat size- and dose-dependent accumulation of sense and antisense RNA foci in C9ORF72 transgenic mice.

(A) FISH detection of sense and antisense RNA foci (arrows) in 2 month old C9450B mice. DNA was stained with DAPI. (B–E) Numbers of sense and antisense foci (per 100 nuclei) in hippocampal dentate gyrus of (B,C) 2 month old C9110, C9450A and C9450B mice, and (D,E) 6 month old heterozygous and homozygous C9450C mice. Error bars represent s.e.m in 3–5 biological replicates. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 using student t test. (F) Quantification of sense RNA foci per nucleus in hippocampal dentate gyrus of 6 month old heterozygous and homozygous C9450C mice. (G) qRT-PCR measurement of human and mouse C9ORF72 RNAs in cortex of 2, 6 and 16 month old C9450B mice, normalized to wild type littermates (n=2–4 per group). (H) Numbers of sense foci (per 100 nuclei) in hippocampal dentate gyrus of 2, 6 and 16 month old C9450B mice. Error bars represent s.e.m in 2–4 biological replicates. n.s., not significant using one way ANOVA.

(See also Figure S3).

Doubling the level of 450 repeat-containing sense strand RNAs (compare RNA levels in C9450B versus C9450A - Figure 2G,H) doubled sense foci accordingly (Figure 3B). Similarly, doubling repeat-containing RNAs by generating homozygous C9450C mice more than doubled the overall number of sense foci (Figure 3D) and the number of foci per cell (Figure 3F). The proportion of cells that developed sense foci also increased from 52% in the dentate gyrus of heterozygous C9450C mice to 81% in homozygous mice (Figure S3I), and some cells accumulated more than 30 sense foci (Figure 3F). Transgene expression and foci burden remained constant with age (Figure 3G,H).

Antisense RNAs from the human C9ORF72 transgene, identified using a strand-specific RT-PCR strategy (Figure S3K,L), also accumulated into RNA foci (Figure 3A). As with sense foci, antisense foci increased with increased repeat length (Figure 3C) and RNA expression level, with both the overall number of antisense foci (Figure 3E) and the percentage of cells with foci (Figure S3I,J) nearly doubling in homozygous versus heterozygous C9450C mice.

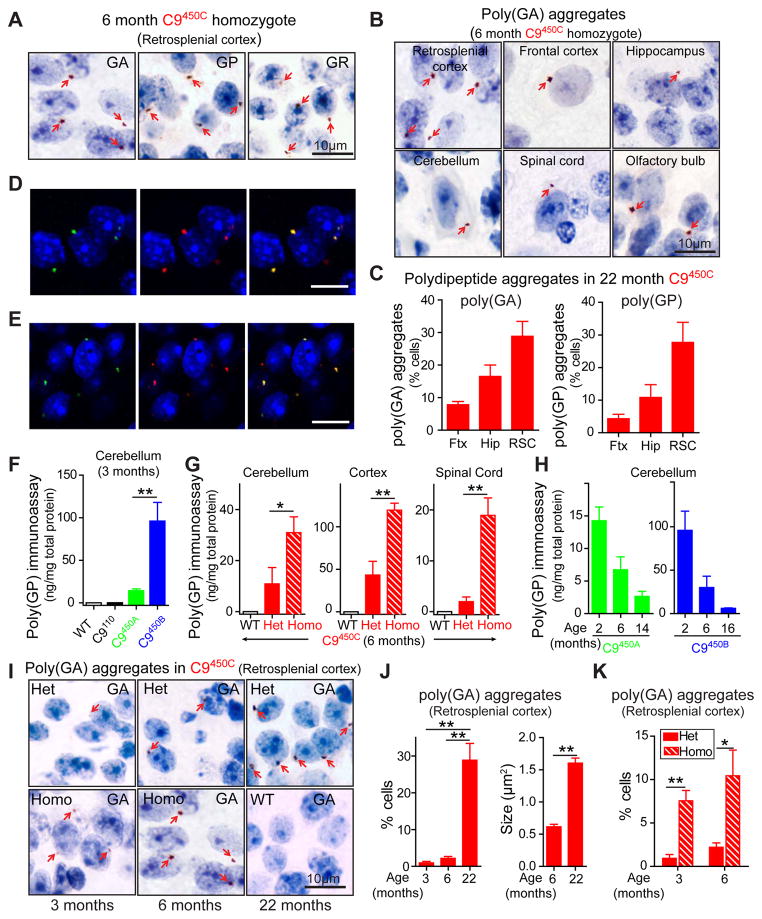

Age-, repeat length- and expression-dependent cytoplasmic inclusions of DPR proteins

Inclusions of DPR proteins produced by RAN translation from GGGGCC or GGCCCC repeats are a neuropathological hallmark of C9ALS/FTD (Ash et al., 2013; Gendron et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2013a; Mori et al., 2013c; Zu et al., 2013). As in human patients, perinuclear, cytoplasmic aggregates of sense strand RNA-encoded poly(GA), poly(GP) or poly(GR) proteins were detected in multiple CNS regions in C9450C mice as young as 3 months of age (Figure 4A,B). Poly(GA) and poly(GP) aggregates in 22 month old C9450C mice were most abundant in the retrosplenial cortex, followed by the hippocampal dentate gyrus and frontal cortex (Figure 4C and S4A). Fewer poly(GA) aggregates were observed in the cerebellum (Figure S4B) or spinal cord. Dot blot assay confirmed accumulation of poly(GP) in cortical lysates from 6 month old C9450C mice (Figure S4C). As in C9ALS/FTD patients (Mori et al., 2013a), DPR proteins co-aggregated into common, p62-containing inclusions (Figure 4D,E and S4D). Antisense strand-encoded poly(PR) and poly(PA) proteins have only been detected in rare aggregates in patient samples (Gendron et al., 2013; Mackenzie et al., 2015; Mori et al., 2013a; Schludi et al., 2015; Zu et al., 2013). None were detected in C9 mice of any line or at any age.

Figure 4. Repeat size- and expression-dependent production of sense strand encoded DPR proteins is associated with age-dependent formation of cytoplasmic inclusions.

(A) Poly(GA), poly(GP) and poly(GR) perinuclear aggregates (arrows) detected by immunohistochemistry in the retrosplenial cortex of 6 month old homozygous C9450C mice. Nuclei were stained with haemalum. (B) Poly(GA) aggregates (arrows) in different CNS regions of 6 month old homozygous C9450C mice. (C) Percent of cells containing poly(GA) or poly(GP) inclusions in frontal cortex (Ftx), hippocampus (Hip) and retrosplenial cortex (RSC) of 22 month old heterozygous C9450C mice (n=2–4 biological replicates). (D) Aggregates positive for (green) poly(GP), (red) poly(GA) or (yellow) both, and (E) (Green) Poly(GP) and (red) P62-positive inclusions identified by immunofluorescence in retrosplenial cortex of 6 month old homozygous C9450C mice. DNA is stained with DAPI. (F–H) Levels of poly(GP) soluble in 2% SDS measured by immunoassay in (F) cerebellum of 3 month old C9110, C9450A and C9450B mice, (G) cerebellum, cortex and spinal cord of 6 month old heterozygous and homozygous C9450C mice, and (H) during aging in the cerebellum of C9450A and C9450B mice (n=2–5 biological replicates). (I) Poly(GA) aggregates (arrows) identified by immunohistochemistry in retrosplenial cortex of heterozygous or homozygous C9450C mice or wild type mice at the noted ages. (J) (left panel) Percent of cells containing poly(GA) aggregates and (right panel) average size of poly(GA) inclusions in retrosplenial cortex of C9450C mice (n=2–3 biological replicates). (K) Percent of cells with poly(GA) inclusions in retrosplenial cortex of heterozygous and homozygous C9450C mice (n=3 per group). Error bars represent s.e.m. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 using student t-test.

(See also Figure S4).

Similar to RNA foci formation, DPR protein expression was dependent on repeat length, as established by immunoassay for quantitative measurements of poly(GP) (Su et al., 2014). Although C9110 mice expressed a 3-fold higher level of repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNAs than C9450B mice (Figure 2H), no poly(GP) was detected in 2% SDS-soluble homogenates prepared from tissues of various neuroanatomical regions from C9110 mice, while poly(GP) was easily detected in mice expressing 450 repeats (Figure 4F). As expected, more poly(GP) was detected in mice with higher C9ORF72 RNA expression (compare C9450A and C9450B mice - Figure 4F - and homozygous C9450C versus age-matched heterozygotes - Figure 4G).

SDS-soluble poly(GP) decreased with age in C9450A and C9450B mice (Figure 4H), despite constant transgene expression (Figure 3G), indicating that DPR proteins may become insoluble over time. Consistent with this notion, poly(GA) aggregated more in the retrosplenial cortex (Figure 4I) and hippocampus (Figure S4E) as mice aged, and the size of poly(GA) inclusions increased over time (Figure 4J). Age-dependent increases in the number and size of poly(GP) and poly(GR) aggregates were also detected (Figure S4F,G). In addition, more cells accumulated DPR protein aggregates in 3 month old C9450C homozygous mice compared to heterozygous mice, and the abundance of such aggregates was increased at 6 months of age (Figures 4I,K, and S4F,G).

Age-dependent cognitive impairment in C9 mice expressing 450 repeats

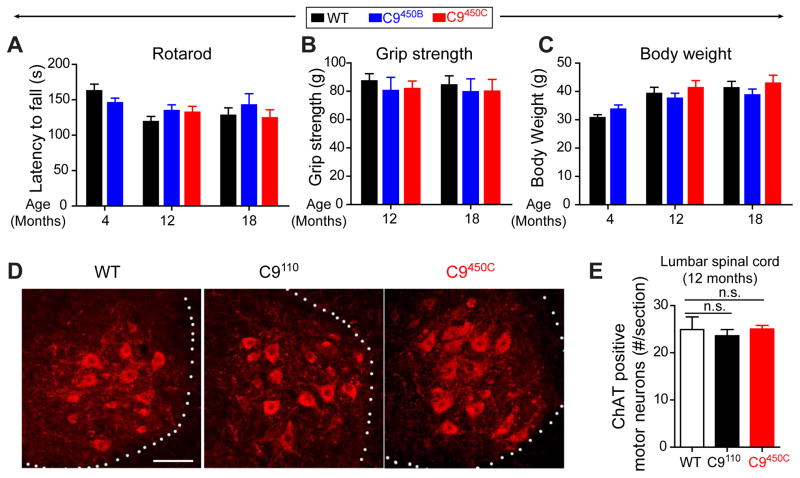

C9 transgenic mice were tested for age-dependent disease. No significant motor deficits or weight loss were observed by 18 months of age in two mouse lines expressing 450 repeats (C9450B or C9450C; Figure 5A–C and S5A,B). By 12 months of age, no loss of ChAT-positive lower motor neurons (Figure 5D,E) or increased glial activation (Figure S5C) was detected in the spinal cord of C9450C mice, which express the highest levels of transgene. Functional innervation and connectivity of the entire neuromuscular unit were normal, as measured by resting EMG recordings and MMEP amplitudes, respectively, in 12 month old C9110 and C9450C mice (Figure S5D,E). There was no loss of CTIP-2-positive upper motor neurons in layer 5 of the motor cortex in either line (Figure S5F).

Figure 5. No motor neuron loss and motor deficits in C9ORF72 transgenic mice with 450 repeats.

(A) Motor performance on a Rotarod measured by latency to fall, (B) hindlimb grip strength, and (C) body weight of 4, 12 and 18 month old wild type (WT), C9450B and C9450C mice. (D) Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT) positive motor neurons detected by immunofluorescence in the anterior horn of lumbar spinal cord of 12 month old WT, C9110 and C9450C mice. (E) Average number of ChAT-positive neurons per section. Error bars represent s.e.m in n=4–5 animals per group. n.s., not significant using one way ANOVA.

(See also Figure S5).

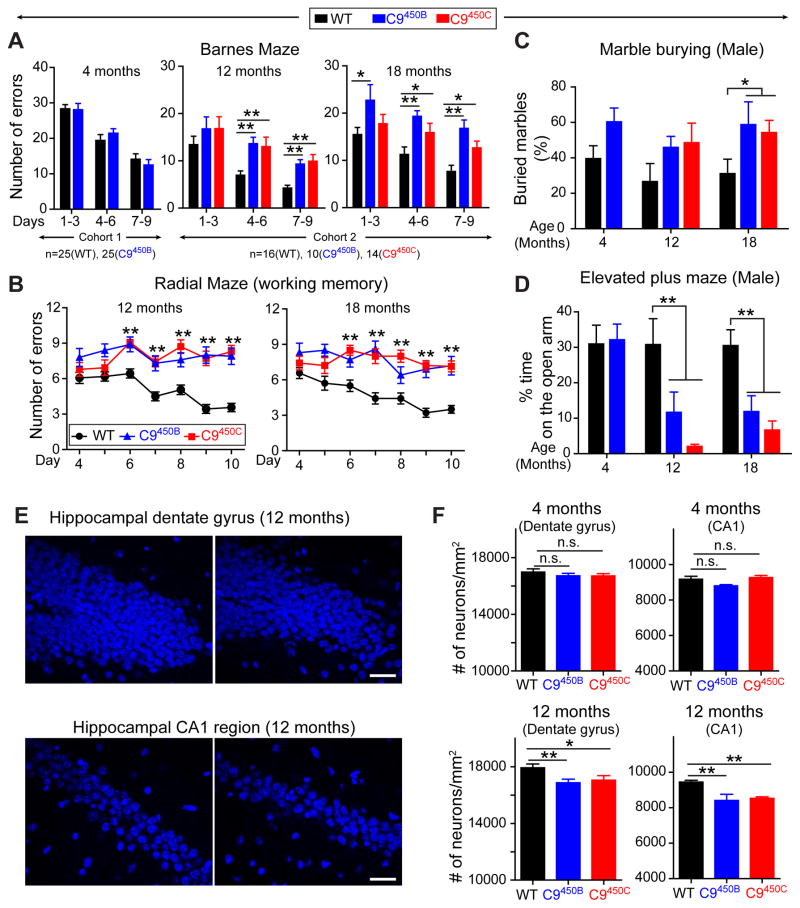

Cognitive and behavioral dysfunction, however, developed in an age-dependent manner. While 4 month old C9450B mice performed as well as wild type littermates in an assay that measures spatial learning and memory (the Barnes maze), both C9450B and C9450C lines developed deficits by 12 months of age that were sustained to 18 months (Figure 6A). A second spatial learning assay (the radial arm maze) confirmed a working memory deficit at 12 and 18 months of age in C9450B and C9450C mice (Figure 6B). Aged C9450B and C9450C male mice also displayed abnormalities in two “anxiety” assays, a marble burying test (Figure 6C) and an elevated plus maze (Figure 6D). The spatial learning and anxiety abnormalities were not accompanied by behavioral differences in social interaction, social recognition, or social communication, nor did assays of novel objection recognition, fear conditioning and serial reversal learning uncover any impairment (Figure S6C–H).

Figure 6. Age-dependent increased anxiety and impaired cognitive function in C9ORF72 mice with 450 repeats.

(A–B) Behavioral performances in WT, C9450B and C9450C mice at 4, 12 and 18 months of age [n=25 mice per group at 4 months and n=16 (WT), n=14 (C9450B) and n=10 (C9450C) at 12 and 18 months of age]. (A) Spatial learning and memory performance on a Barnes maze showing the number of errors in finding the escape chamber at days 1–3, 4–6 and 7–9. (B) Working memory performance on a radial maze showing errors per trial over 10 days of testing. (C–D) Anxiety-related behaviors in WT, C9450B and C9450C male mice at 4, 12 and 18 months of age [n=11 (WT) and n=13 (C9450B) at 4 months, and n=9 (WT), n=4 (C9450B) and n=7 (C9450C) at 12 and 18 months of age]. (C) Anxiety-related behavior determined by marble burying test showing the percent of marbles buried during a 20-minute trial, and (D) elevated plus maze showing the percent of time spent on the open arm. (E) Representative images and (F) quantification of DAPI-positive nuclei in the hippocampal dentate gyrus and CA1 region in 4 and 12 month old WT, C9450B and C9450C mice (n=4–5 per group). Error bars represent s.e.m, n.s., not significant, * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01 using one-way ANOVA.

(See also Figure S6 and S7).

Recognizing the crucial role of the hippocampus in spatial learning and memory (Sharma et al., 2010), we tested the C9 mice for age-dependent hippocampal neuron loss. Blinded quantification in two hippocampal regions (the dentate gyrus and CA1 region) of 4 and 12 month old C9450B and C9450C mice identified mild, age-dependent neuronal loss (Figure 6E,F). Neuronal loss was repeat length-dependent, as no loss was seen in C9110 mice that expressed higher levels of repeat-containing RNAs than C9450C mice (Figure S7A). No astrogliosis or microgliosis was observed, and neuronal loss was region specific, as the neuronal density in the retrosplenial cortex remained unchanged (Figure S7A). Although levels of both sarkosyl-soluble and sarkosyl-insoluble (but urea soluble) phosphorylated TDP-43 (pTDP-43) were significantly increased in 22 month old C9450C mice (Figure S7C), no TDP-43 mislocalization or aggregation was observed (Figure S7B). Similarly, no mislocalized, discontinuous or punctate aggregates of RanGAP1 or Lamin B (Figure S7D,E) were identified.

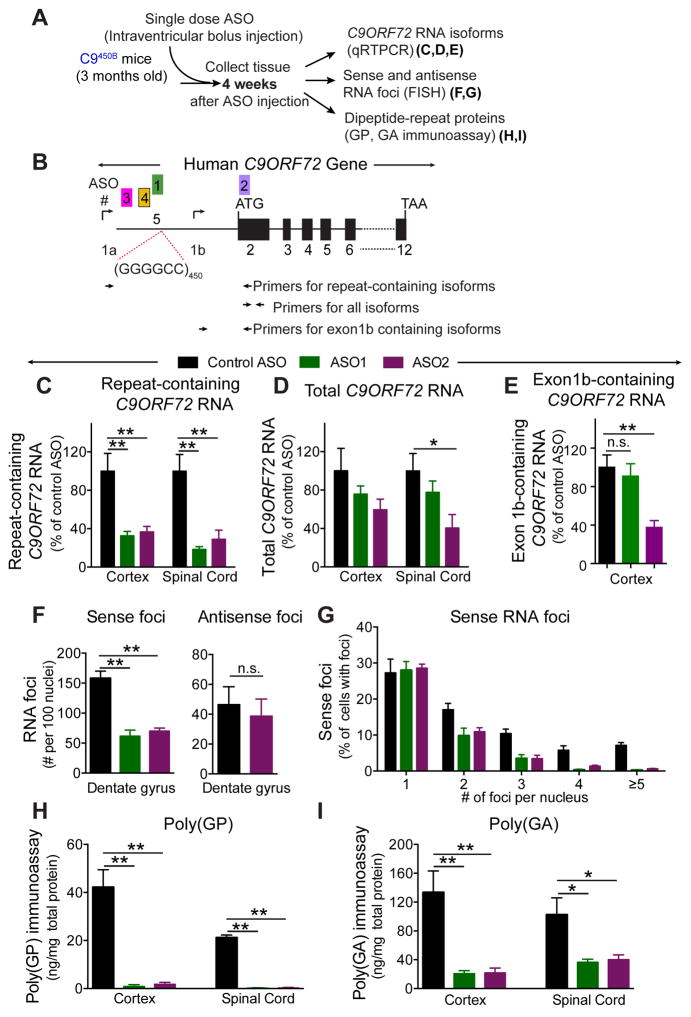

Single dose ASOs reduce foci, DPR proteins, and behavioral deficits in C9 mice

ASOs mediate cleavage of target RNAs through action of the primarily nuclear enzyme RNase H and ASO therapy has gone to clinical trial for ALS (Miller et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2006) and at least two neurodegenerative disorders linked to repeat expansions: myotonic dystrophy (Wheeler et al., 2012) and Huntington’s disease (Kordasiewicz et al., 2012). To test whether in vivo administration of ASOs can mediate RNase H-dependent, selective reduction of C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat-containing RNAs in the rodent CNS, 3 month old C9450B mice were treated with a single intraventricular bolus injection of ASOs targeting human C9ORF72 RNAs or a control ASO that does not have any target in the mouse genome (Figure 7A). One C9ORF72 ASO (ASO1) was complementary to a sequence that partially overlaps the 5′-end of the hexanucleotide expansion and specifically targets repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNA variants. A second ASO (ASO2) hybridizes within exon 2 and thus targets all C9ORF72 RNA variants (Figure 7B). Four weeks after a single injection, both ASO1 and ASO2 decreased repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNA levels in the cortex and spinal cord to 20–40% of levels in control ASO-treated mice (Figure 7C). As expected, ASO2 decreased total and exon 1b containing C9ORF72 RNAs by 40–60%. However, ASO1, which targets repeat RNA, preserved exon 1b-containing, C9ORF72 protein encoding RNAs (Figure 7E) and 80% of total C9ORF72 RNAs (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Sustained reduction in RNA foci and DPR proteins from a single dose of ASOs targeting C9ORF72 repeat-containing RNAs.

(A) Schematic of injected ASOs targeting the sense strand C9ORF72 transcripts for degradation in 3 month old C9450B mice. (B) Schematic of the C9ORF72 gene showing the GGGGCC repeats within the first intron, the two transcription initiation sites (arrows), the positions of five ASOs, and primers for detection (by qRT-PCR) of various C9ORF72 RNAs. (C–E) Expression of (C) repeating-containing, (D) total and (E) exon 1b-containing C9ORF72 RNAs determined by qRT-PCR in mice treated either with ASO1 targeting only the repeat-containing RNAs, ASO2 targeting all C9orf72 variants, or a control ASO. (F) Number of sense and antisense foci (per 100 nuclei) determined by FISH and (G) quantification of sense foci per nucleus in hippocampal dentate gyrus. (H–I) Levels of (H) poly(GP) or (I) poly(GA) in the cortex and spinal cord of C9450B mice treated with ASO1, ASO2 or a control ASO, as measured by immunoassay. Error bars represent s.e.m in n=5–6 biological replicates. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, n.s. not significant using one-way ANOVA.

(See also Figure S8).

Within four weeks after a single injection of either ASO1 or ASO2, the number of sense foci were reduced to 40–45% (Figure 7F,G). Antisense RNA foci remained unchanged (Figure 7F). Both SDS-soluble poly(GP) and poly(GA) were decreased to almost undetectable levels in the cortex and spinal cord (Figure 7H,I). The profound reduction of poly(GP), which can be translated from sense or antisense strand RNAs, demonstrates that in our transgenic mice poly(GP) proteins are mostly translated from sense strand RNAs.

Selective reduction of repeat-containing RNAs with attenuated RNA foci and RAN translation was confirmed by single dose injection of two additional ASOs (ASO3 and ASO4) targeting sequences 5′ to the expansion within C9ORF72 intron 1 (Figure 7B and S8A). Two weeks after treatment, repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNAs in cortex and spinal cord were reduced to 40% of a PBS-treated group, with total C9ORF2 RNAs remaining at 80% of their initial level (Figure S8B,C). Sense foci were reduced by half; antisense foci were unaffected. SDS soluble poly(GP) levels were reduced by more than 80% in cortex and 50% in spinal cord (Figure S7D) and poly(GP) aggregates, quantified in a blinded fashion, were significantly decreased in ASO3- or ASO4-treated mice (Figure S8E,F). Thus, intron 1-targeting ASOs rapidly decrease both soluble and insoluble DPR proteins throughout the mouse CNS.

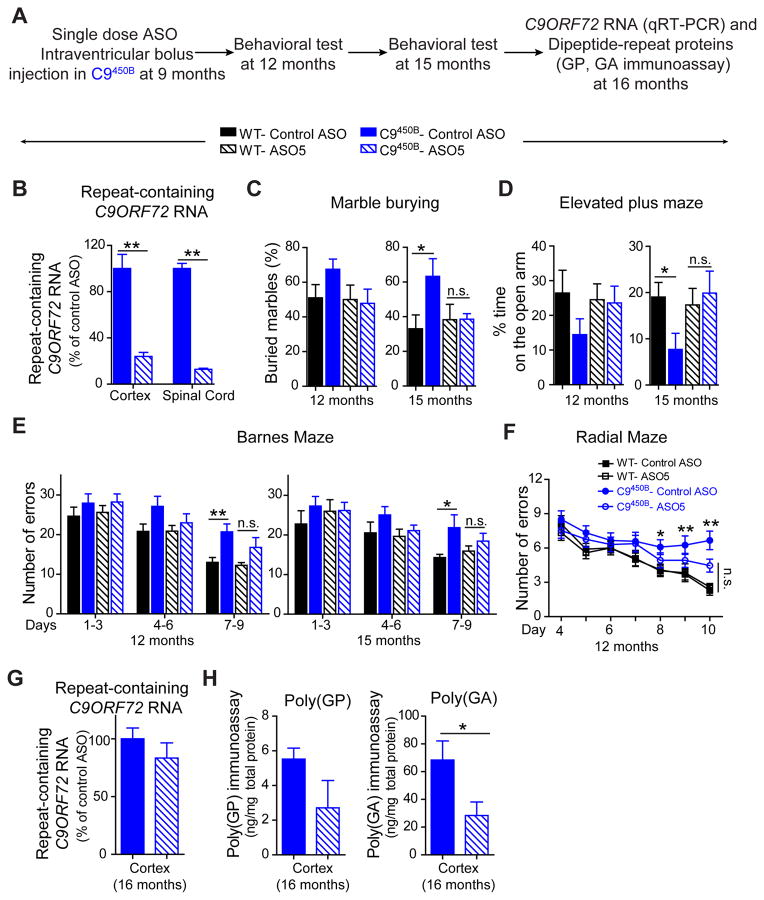

Finally, 9 month old C9450B mice were injected with an ASO targeted to repeat-containing RNAs (Figure 8A). Repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNAs in the cortex and spinal cord were sharply reduced (to 23% and 12% of control levels, respectively) within two weeks of treatment (Figure 8B). Consistent with our assays with an independent cohort (Figure 6A–D), C9450B mice injected with a control ASO developed increased anxiety (in marble burying test and elevated plus maze), and impaired cognition (in Barnes and radial mazes) (Figure 8C–F). Single dose ASO injection at 9 months alleviated these age-dependent deficits (Figure 8C–F). In fact, at 15 months (6 months after injection), the beneficial effects were sustained, with a trend suggestive of further improvement. Correspondingly, SDS-soluble poly(GP) and poly(GA) levels remained lower in 16 month old mice treated with the repeat-targeting ASO (Figure 8H), even though repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNA levels had recovered to their initial level (Figure 8G).

Figure 8. Single dose ASO treatment alleviates age-dependent behavioral deficits in C9ORF72 mice expressing 450 repeats.

(A) Schematic of the experimental procedure for a single dose ASO targeting degradation of the sense strand C9ORF72 RNA in 9 month old C9450B mice. (B) Expression of repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNAs was determined by qRT-PCR 2 weeks after injection of ASO5 or control ASO (n=6 per group). (C–D) Anxiety-related behaviors determined by (C) marble burying test and (D) elevated plus maze in 12 and 15 month old WT and C9450B mice treated with either control ASO or ASO5 (n=5–7 per group). (E–F) Cognition-related behaviors determined on (E) a Barnes maze and (F) a radial maze in 12 and 15 month old WT and C9450B mice treated with either control ASO or ASO5 (n=10–13 per group). (G) Expression of repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNAs and (H) levels of poly(GP) or poly(GA) proteins in the cortex of 16 month old C9450B mice treated at 9 months with ASO5 or control ASO. Error bars represent s.e.m. Error bars represent s.e.m in biological replicates * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, n.s. not significant, using student t test.

Discussion

A key question regarding pathogenic mechanisms in C9ALS/FTD has been whether the repeat expansion causes disease through loss of C9ORF72 function, gain of toxicity from repeat RNA, or both. By producing and analyzing mice with a chronic reduction of C9ORF72 or that express the human C9ORF72 gene with different sizes of expanded repeats, we have identified gain of toxicity as a central disease mechanism in a mammalian nervous system. Mice expressing RNAs with 450 repeats from two independent lines developed age-dependent anxiety-like behavior and impaired cognitive function by 12 months of age, accompanied by mild hippocampal neuronal loss. In contrast, mice hemizygous for C9ORF72 that express 50% of C9orf72 mRNA, as observed in C9ALS/FTD patients (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Gijselinck et al., 2012; van Blitterswijk et al., 2015), did not develop an ALS/FTD-like phenotype or any other phenotype in the CNS or periphery. Hence, by a systematic comparison of multiple mouse lines we now demonstrate that reduction of C9ORF72 expression is not sufficient to trigger neurodegeneration in mice, while pathological hallmarks of C9ALS/FTD, neuronal loss and cognitive dysfunction develop in mice expressing expanded repeat RNA.

The function of the 54 kD C9ORF72 protein has not been established, but its sequence homology to the DENN protein family predicts a possible role in regulating membrane trafficking (Farg et al., 2014; Levine et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012). The C9orf72 gene is expressed not only in the CNS but also in peripheral tissues including spleen (Suzuki et al., 2013), bone marrow, lymphocytes and macrophages (BioGPS data; www.biogps.org). By disrupting both C9orf72 alleles, we determined that complete elimination of C9ORF72 from mice produces splenomegaly, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, and premature death. While loss of C9ORF72 during embryonic development has been reported to produce motor deficits in zebrafish (Ciura et al., 2013) and C. elegans (Therrien et al., 2013), systemic (our work here and (Atanasio et al., 2016; Koppers et al., 2015; O’Rourke et al., 2016)) or nestin-cre (Koppers et al., 2015) mediated ablation of C9orf72 in mice is not associated with motor degeneration, defects in motor function or altered survival. In addition, no loss of function mutations in C9ORF72, including nonsense or frame shift mutations, have been linked to ALS or FTD (Harms et al., 2013), and reduced expression of expanded RNAs following hypermethylation of the C9ORF72 promoter may actually be neuroprotective (Liu et al., 2014; McMillan et al., 2015; Russ et al., 2015). While our studies reinforce conclusions that C9ORF72 plays an important role in immune cells (Atanasio et al., 2016; O’Rourke et al., 2016), chronic reduction of C9ORF72 alone is not sufficient to cause ALS/FTD symptoms in mice. A key remaining question, now testable with the mice we report here, is whether reduction in C9ORF72 synergizes with repeat-mediated gain of toxicity to potentiate disease.

Our analysis uncovered an unexpected association between hexanucleotide repeat-length and accumulation of RNA foci and DPR proteins. When expressed at 7 times the level of an endogenous C9orf72 allele, no detectable DPR proteins accumulate in mice expressing 110 repeats (Figure 4F). Conversely, mice with lower RNA levels but with 450 repeats produce both soluble DPR proteins (Figure 4F,G,H) and insoluble aggregates (Figure 4I,J,K). That no DPR proteins were detected in C9110 mice could be due to: 1) RAN translation initiation of short repeats being less efficient than of long repeats; 2) shorter DPR proteins having shorter half-lives than longer DPR proteins; 3) shorter repeat-containing RNAs being less effectively transported to the cytoplasm, the presumed site of RAN translation; or 4) a combination of options 1–3.

While a prior study demonstrated that robust adeno-associated virus-mediated expression of 66 GGGGCC repeats led to the aggregation of DPR proteins throughout the murine CNS (Chew et al., 2015), we demonstrate here that expression of a short repeat does not generate such pathology in mouse brain when expressed at 7 times the levels of RNA from a single C9orf72 allele. Not only do long and short repeats have differing capacities to generate DPR proteins, long and short DPR proteins have different intracellular localization and aggregation profiles. For instance, DPR proteins translated from 66 repeats produced a level of accumulated poly(GP) that reached 1.8% of total brain protein by 6 months of age and formed primarily nuclear aggregates (Chew et al., 2015), whereas we and others (O’Rourke et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2015) have shown that, in mice with 400–500 repeats, DPR proteins form cytoplasmic inclusions similar to those observed in C9ALS/FTD patients. Short DPR proteins are likely to be more soluble and sufficiently small to freely diffuse through nuclear pores, thereby facilitating the intranuclear aggregation of DPR proteins seen in mice expressing 66 repeats (Chew et al., 2015). Similarly, the nucleolar disruption and acute toxicity resulting from exposing cultured cells to 10 μM of 20 mer poly(PR) or poly(GR) proteins (Kwon et al., 2014) differs markedly from the primarily cytoplasmic aggregates observed in mice expressing 450 repeats and C9ALS/FTD patients (Ash et al., 2013; Gendron et al., 2013; Mackenzie et al., 2015; Mori et al., 2013a; Zu et al., 2013).

While the minimal pathogenic repeat size in C9ORF72 patients is not established, somatic expansion can take the germline transmitted repeat to 3000–5000 repeats in the most affected brain regions (Gijselinck et al., 2015; van Blitterswijk et al., 2013). We have found minimal somatic expansion in either the CNS or peripheral tissues of mice. Also differing from C9ALS/FTD patients, our C9450 mice did not display TDP-43 mislocalization or aggregation, although increased levels of phosphorylated TDP-43 were detected. In addition, we did not observe mislocalization of proteins involved in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Lack of these features may explain the relatively mild phenotype observed in our transgenic mice despite expression of up to 24 times a single endogenous C9orf72 allele. While abundant RNA foci did not increase with age in our mice, an age- and repeat length-dependent increase in the number and size of cytoplasmic DPR aggregates was seen, with soluble poly(GP) levels decreasing with age (Figure 4H). In C9ALS/FTD, the anatomical distribution of DPR protein pathology does not correlate with neurodegeneration (Schludi et al., 2015). These findings suggest that certain neuroanatomical regions are less susceptible to DPR proteins, or that soluble DPR proteins are toxic and DPR protein aggregates are neuroprotective. In support of the latter, poly(GA) can recruit poly(GR) into inclusions and partially decreases poly(GR) toxicity in Drosophila and cultured cell models (Yang et al., 2015). On the other hand, aggregation of poly(GA) was recently reported to be necessary for its toxicity, which is mediated through sequestration of HR23 and nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins (Zhang et al., 2016).

Despite uncertainty about the contributions of RNA foci or DPR proteins to neurodegeneration, an “on mechanism” therapy would be one that reduces repeat-containing RNAs, thereby attenuating both potential toxicities. We have established the potency of multiple ASOs for selective reduction of repeat-containing C9ORF72 RNAs in the mammalian CNS while having minimal effect on total C9ORF72 RNAs. Importantly, single dose ASO: 1) significantly mitigated the accumulation of sense RNA foci (without increasing antisense foci) and of poly(GP) and poly(GA) proteins; and 2) significantly attenuated the development of behavioral deficits even 6 months after a single injection. Thus, our studies establish a repeat-dependent gain of toxicity as a crucial pathological mechanism of C9ALS/FTD and, most importantly, validate the feasibility of employing ASO therapy to mitigate the toxicity from repeat RNAs without exacerbating a potential loss of C9ORF72 function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Please see the Supplemental Experimental Procedures for more information

Generation of C9ORF72 BAC transgenic mice

The human BAC construct expressing a truncated C9ORF72 gene with 450 repeat expansions was obtained from BACPAC resource center at Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute (Clone ID: CH523–111K12) and was injected into the pronuclei of fertilized C57BL6/C3H hybrid eggs and implanted into pseudo-pregnant female mice. Mice used in this report were then backcrossed to C57BL/6 for a minimum of three generations. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California San Diego.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Procedures are detailed in Supplementary information. Primers and probe sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Generation of antibodies recognizing DPR proteins

Peptide antigens (C-Ahx-(GA)8-amide, C-Ahx-(GR)8-amide, C-Ahx-(PR)8-amide, C-Ahx-(GP)8-amide and C-Ahx-(PA)8-amide) were used to immunize rabbits to generate antibodies against DPR proteins. Pre-immune serum from each rabbit was tested using peptide antigens and tissue from C9ALS/FTD cases by immunoblot and immunohistochemistry, respectively, and confirmed negative. Antiserum or affinity purified antibodies were used. Antibodies specific for each DPR protein are herein annotated Rb4333 poly(GA), Rb4335 poly(GP), Rb4995 poly(GR), Rb15898 poly(PA) and Rb15986 poly(PR).

Immunofluorescence staining and X-gal staining

Sections from paraformaldehyde-fixed tissues were stained using standard protocols with antibodies against GFAP (Chemicon, 1:1000), IBA1 (Wako, 1:500), ChAT (Millipore, 1:300), NeuN (GeneTex, 1:1000), CTIP2 (Abcam 1:500), poly(GA) (Rb4333, 1:1000); poly(GP) (Rb4335,1:1000), poly(GR) (Rb4995,1:1000), poly(PR) (Rb15986, 1:100), poly(PA) (Rb15989, 1:100), TDP-43 (Proteintech, 1:500), RanGAP1 (Santa Cruz, 1:500), Lamin B (Santa Cruz, 1:20,000) and P62 (Abnova, 1:100). Confocal images were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse laser scanning confocal microscope using the Nikon EZ-C1 software. LacZ activity was assessed with X-gal staining solution (1.0 mg/ml of X-gal, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 2 mM MgCl2) for 12 h at 37°C. The sections were examined and photographed with a Nanozoomer.

Injection of ASO in the mouse CNS

Intra cerebroventricular (ICV) stereotactic injections of 10 μl of ASO solution, corresponding to a total of 350 μg of ASOs (Ionis Pharmaceuticals), were administered into the right ventricle using the following coordinates: 0.2 mm posterior and 1.0 mm lateral to the right from the bregma and 3 mm deep. Mice were treated either with PBS, a control ASO, or ASOs targeting total C9ORF72 (ASO2), or repeat-containing C9ORF72 variants (ASO1,3,4,5). The sequence of the ASOs is available in Supplemental Table 2.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

C9ORF72 repeat expansions cause age, repeat size and expression dependent toxicity

Disease from expansions in C9ORF72 is from acquired toxicity not loss of function

Absence of C9ORF72 in mice produces splenomegaly and enlarged cervical lymph nodes

ASO-induced decreases in repeat RNA mitigate C9ORF72-associated phenotypes in vivo

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrick King, Clement Ng, Cheyenne Schloffman, Marcus Maldonado, Anh Bui, and Drs. Ricardos Tabet, Kent Osborn, Nissi Varki for their advices and technical assistance. We thank all members of DWC, CLT and JR groups and the team at Ionis Pharmaceuticals for critical suggestions on this project. This work was supported by the ALS Association (a Neurocollaborative grant to DWC; grants to TFG and LP; a Milton Safenowitz postdoctoral fellowship to QZ), grants from the NIH (R01-NS088578 to JR and DWC, R01-NS087227 to CLT, R21-NS089979 to TFG, as well as R21-NS084528, R01-NS088689, R01-NS063964, R01-NS077402 and P01-NS084974 to LP), the UCSD Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (to CLT), research project funding from Target ALS to CLT (13-04827), JR (13-44792) and LP, the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins (to LP), the Mayo Clinic Foundation (to LP), a senior clinical investigatorship and a grant from FWO-Vlaanderen to PVD, the Belgian Alzheimer Disease Association (SAO; to PVD) and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2014-2019 under grant agreement n° 617198 [DPR-MODELS] (to DE). JJ was supported by NIH postdoctoral fellowships (T32 AG00216 and F32 NS087842). SS is the recipient of career development grants from the NIH (K99 NS091538) and Target ALS. LDM is employed by Janssen, Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson. PJ, SC, JE, AW, CFB and FR are employees and DWC is a consultant for Ionis Pharmaceuticals. JR received salary support from the University of California, San Diego. CLT and DWC received salary support from the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JJ, QZ, TFG, PJ, SS, SCL, MM, CJH, PVD, DU, AD, SMH, LP, CFB, SDC, JR, FR, DWC and CLT. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. JJ, QZ, TFG, SS, JES, PJ, KD, DS, SC, AS, SS, SCL, MMD, BM, JE, MK, MB, OP, AW, CH, LDM, LD, AD and DU performed the experiments. CA, DS, LT, CJJ, PDJ, DE, SMH and CES contributed key reagents and methodology. JJ, QZ, TG, DWC and CLT wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ash PE, Bieniek KF, Gendron TF, Caulfield T, Lin WL, Dejesus-Hernandez M, van Blitterswijk MM, Jansen-West K, Paul JW, 3rd, Rademakers R, et al. Unconventional translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion generates insoluble polypeptides specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron. 2013;77:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasio A, Decman V, White D, Ramos M, Ikiz B, Lee HC, Siao CJ, Brydges S, LaRosa E, Bai Y, et al. C9orf72 ablation causes immune dysregulation characterized by leukocyte expansion, autoantibody production, and glomerulonephropathy in mice. Scientific reports. 2016;6:23204. doi: 10.1038/srep23204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzil VV, Bauer PO, Prudencio M, Gendron TF, Stetler CT, Yan IK, Pregent L, Daughrity L, Baker MC, Rademakers R, et al. Reduced C9orf72 gene expression in c9FTD/ALS is caused by histone trimethylation, an epigenetic event detectable in blood. Acta neuropathologica. 2013;126:895–905. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeynaems S, Bogaert E, Michiels E, Gijselinck I, Sieben A, Jovicic A, De Baets G, Scheveneels W, Steyaert J, Cuijt I, et al. Drosophila screen connects nuclear transport genes to DPR pathology in C9ALS/FTD. Scientific reports. 2016;6:20877. doi: 10.1038/srep20877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew J, Gendron TF, Prudencio M, Sasaguri H, Zhang YJ, Castanedes-Casey M, Lee CW, Jansen-West K, Kurti A, Murray ME, et al. Neurodegeneration. C9ORF72 repeat expansions in mice cause TDP-43 pathology, neuronal loss, and behavioral deficits. Science (New York, NY) 2015;348:1151–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciura S, Lattante S, Le Ber I, Latouche M, Tostivint H, Brice A, Kabashi E. Loss of function of C9orf72 causes motor deficits in a zebrafish model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Annals of neurology. 2013;74:180–187. doi: 10.1002/ana.23946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Knock J, Walsh MJ, Higginbottom A, Robin Highley J, Dickman MJ, Edbauer D, Ince PG, Wharton SB, Wilson SA, Kirby J, et al. Sequestration of multiple RNA recognition motif-containing proteins by C9orf72 repeat expansions. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2014;137:2040–2051. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin AC, Burr K, Borooah S, Foster JD, Cleary EM, Geti I, Vallier L, Shaw CE, Chandran S, Miles GB. Human iPSC-derived motoneurons harbouring TARDBP or C9ORF72 ALS mutations are dysfunctional despite maintaining viability. Nature communications. 2015;6:5999. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly CJ, Zhang PW, Pham JT, Heusler AR, Mistry NA, Vidensky S, Daley EL, Poth EM, Hoover B, Fines DM, et al. RNA Toxicity from the ALS/FTD C9ORF72 Expansion Is Mitigated by Antisense Intervention. Neuron. 2013;80:415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farg MA, Sundaramoorthy V, Sultana JM, Yang S, Atkinson RA, Levina V, Halloran MA, Gleeson PA, Blair IP, Soo KY, et al. C9ORF72, implicated in amytrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia, regulates endosomal trafficking. Human molecular genetics. 2014;23:3579–3595. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freibaum BD, Lu Y, Lopez-Gonzalez R, Kim NC, Almeida S, Lee KH, Badders N, Valentine M, Miller BL, Wong PC, et al. GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9orf72 compromises nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature. 2015;525:129–133. doi: 10.1038/nature14974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron TF, Belzil VV, Zhang YJ, Petrucelli L. Mechanisms of toxicity in C9FTLD/ALS. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;127:359–376. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1237-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron TF, Bieniek KF, Zhang YJ, Jansen-West K, Ash PE, Caulfield T, Daughrity L, Dunmore JH, Castanedes-Casey M, Chew J, et al. Antisense transcripts of the expanded C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat form nuclear RNA foci and undergo repeat-associated non-ATG translation in c9FTD/ALS. Acta neuropathologica. 2013;126:829–844. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1192-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron TF, van Blitterswijk M, Bieniek KF, Daughrity LM, Jiang J, Rush BK, Pedraza O, Lucas JA, Murray ME, Desaro P, et al. Cerebellar c9RAN proteins associate with clinical and neuropathological characteristics of C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers. Acta neuropathologica. 2015;130:559–573. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1474-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijselinck I, Van Langenhove T, van der Zee J, Sleegers K, Philtjens S, Kleinberger G, Janssens J, Bettens K, Van Cauwenberghe C, Pereson S, et al. A C9orf72 promoter repeat expansion in a Flanders-Belgian cohort with disorders of the frontotemporal lobar degeneration-amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spectrum: a gene identification study. Lancet neurology. 2012;11:54–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijselinck I, Van Mossevelde S, van der Zee J, Sieben A, Engelborghs S, De Bleecker J, Ivanoiu A, Deryck O, Edbauer D, Zhang M, et al. The C9orf72 repeat size correlates with onset age of disease, DNA methylation and transcriptional downregulation of the promoter. Molecular psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.159. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms MB, Cady J, Zaidman C, Cooper P, Bali T, Allred P, Cruchaga C, Baughn M, Libby RT, Pestronk A, et al. Lack of C9ORF72 coding mutations supports a gain of function for repeat expansions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiology of aging. 2013;34:2234, e2213–2239. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman M, Schaefer A, Gong S, Peterson JD, Day M, Ramsey KE, Suarez-Farinas M, Schwarz C, Stephan DA, Surmeier DJ, et al. A translational profiling approach for the molecular characterization of CNS cell types. Cell. 2008;135:738–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukema RK, Riemslagh FW, Melhem S, van der Linde HC, Severijnen LA, Edbauer D, Maas A, Charlet-Berguerand N, Willemsen R, van Swieten JC. A new inducible transgenic mouse model for C9orf72-associated GGGGCC repeat expansion supports a gain-of-function mechanism in C9orf72-associated ALS and FTD. Acta neuropathologica communications. 2014;2:166. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0166-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Jovicic A, Mertens J, Boeynaems S, Bogaert E, Chai N, Yamada SB, Paul JW, 3rd, Sun S, Herdy JR, Bieri G, et al. Modifiers of C9orf72 dipeptide repeat toxicity connect nucleocytoplasmic transport defects to FTD/ALS. Nature neuroscience. 2015;18:1226–1229. doi: 10.1038/nn.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppers M, Blokhuis AM, Westeneng HJ, Terpstra ML, Zundel CA, Vieira de Sa R, Schellevis RD, Waite AJ, Blake DJ, Veldink JH, et al. C9orf72 ablation in mice does not cause motor neuron degeneration or motor deficits. Annals of neurology. 2015;78:426–438. doi: 10.1002/ana.24453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordasiewicz HB, Stanek LM, Wancewicz EV, Mazur C, McAlonis MM, Pytel KA, Artates JW, Weiss A, Cheng SH, Shihabuddin LS, et al. Sustained therapeutic reversal of Huntington’s disease by transient repression of huntingtin synthesis. Neuron. 2012;74:1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon I, Xiang S, Kato M, Wu L, Theodoropoulos P, Wang T, Kim J, Yun J, Xie Y, McKnight SL. Poly-dipeptides encoded by the C9orf72 repeats bind nucleoli, impede RNA biogenesis, and kill cells. Science (New York, NY) 2014;345:1139–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.1254917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier-Tourenne C, Baughn M, Rigo F, Sun S, Liu P, Li HR, Jiang J, Watt AT, Chun S, Katz M, et al. Targeted degradation of sense and antisense C9orf72 RNA foci as therapy for ALS and frontotemporal degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:E4530–4539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318835110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YB, Chen HJ, Peres JN, Gomez-Deza J, Attig J, Stalekar M, Troakes C, Nishimura AL, Scotter EL, Vance C, et al. Hexanucleotide repeats in ALS/FTD form length-dependent RNA foci, sequester RNA binding proteins, and are neurotoxic. Cell reports. 2013;5:1178–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine TP, Daniels RD, Gatta AT, Wong LH, Hayes MJ. The product of C9orf72, a gene strongly implicated in neurodegeneration, is structurally related to DENN Rab-GEFs. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2013;29:499–503. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling SC, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron. 2013;79:416–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu EY, Russ J, Wu K, Neal D, Suh E, McNally AG, Irwin DJ, Van Deerlin VM, Lee EB. C9orf72 hypermethylation protects against repeat expansion-associated pathology in ALS/FTD. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;128:525–541. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1286-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IR, Frick P, Grasser FA, Gendron TF, Petrucelli L, Cashman NR, Edbauer D, Kremmer E, Prudlo J, Troost D, et al. Quantitative analysis and clinico-pathological correlations of different dipeptide repeat protein pathologies in C9ORF72 mutation carriers. Acta neuropathologica. 2015;130:845–861. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IR, Frick P, Neumann M. The neuropathology associated with repeat expansions in the C9ORF72 gene. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;127:347–357. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May S, Hornburg D, Schludi MH, Arzberger T, Rentzsch K, Schwenk BM, Grasser FA, Mori K, Kremmer E, Banzhaf-Strathmann J, et al. C9orf72 FTLD/ALS-associated Gly-Ala dipeptide repeat proteins cause neuronal toxicity and Unc119 sequestration. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;128:485–503. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1329-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan CT, Russ J, Wood EM, Irwin DJ, Grossman M, McCluskey L, Elman L, Van Deerlin V, Lee EB. C9orf72 promoter hypermethylation is neuroprotective: Neuroimaging and neuropathologic evidence. Neurology. 2015;84:1622–1630. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TM, Pestronk A, David W, Rothstein J, Simpson E, Appel SH, Andres PL, Mahoney K, Allred P, Alexander K, et al. An antisense oligonucleotide against SOD1 delivered intrathecally for patients with SOD1 familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase 1, randomised, first-in-man study. Lancet neurology. 2013;12:435–442. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizielinska S, Gronke S, Niccoli T, Ridler CE, Clayton EL, Devoy A, Moens T, Norona FE, Woollacott IO, Pietrzyk J, et al. C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science (New York, NY) 2014;345:1192–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1256800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizielinska S, Lashley T, Norona FE, Clayton EL, Ridler CE, Fratta P, Isaacs AM. C9orf72 frontotemporal lobar degeneration is characterised by frequent neuronal sense and antisense RNA foci. Acta neuropathologica. 2013;126:845–857. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1200-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Arzberger T, Grasser FA, Gijselinck I, May S, Rentzsch K, Weng SM, Schludi MH, van der Zee J, Cruts M, et al. Bidirectional transcripts of the expanded C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat are translated into aggregating dipeptide repeat proteins. Acta neuropathologica. 2013a;126:881–893. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Lammich S, Mackenzie IR, Forne I, Zilow S, Kretzschmar H, Edbauer D, Janssens J, Kleinberger G, Cruts M, et al. hnRNP A3 binds to GGGGCC repeats and is a constituent of p62-positive/TDP43-negative inclusions in the hippocampus of patients with C9orf72 mutations. Acta neuropathologica. 2013b;125:413–423. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Weng SM, Arzberger T, May S, Rentzsch K, Kremmer E, Schmid B, Kretzschmar HA, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C, et al. The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science (New York, NY) 2013c;339:1335–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.1232927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke G, Bogdanik L, Muhammad AKMG, Gendron TF, Kim KJ, Austin A, Cady J, Liu EY, Zarrow J, Grant S, et al. C9orf72 BAC transgenic mice display typical pathologic features of ALS/FTD. Neuron. 2015;88:892–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke JG, Bogdanik L, Yanez A, Lall D, Wolf AJ, Muhammad AK, Ho R, Carmona S, Vit JP, Zarrow J, et al. C9orf72 is required for proper macrophage and microglial function in mice. Science (New York, NY) 2016;351:1324–1329. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters OM, Cabrera GT, Tran H, Gendron TF, McKeon JE, Metterville J, Weiss A, Wightman N, Salameh J, Kim J, et al. Human C9orf72 hexanucleotide expansion reproduces RNA foci and dipeptide repeat proteins but not neurodegeneration in BAC transgenic mice. Neuron. 2015;88:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simon-Sanchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L, et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron. 2011;72:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, Serrano A, Gerbino V, Giorgi A, Di Francesco L, Nencini M, Bozzo F, Schinina ME, Bagni C, Cestra G, et al. Nuclear accumulation of mRNAs underlies G4C2-repeat-induced translational repression in a cellular model of C9orf72 ALS. Journal of cell science. 2015;128:1787–1799. doi: 10.1242/jcs.165332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ J, Liu EY, Wu K, Neal D, Suh E, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Harms MB, Cairns NJ, Wood EM, et al. Hypermethylation of repeat expanded C9orf72 is a clinical and molecular disease modifier. Acta neuropathologica. 2015;129:39–52. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1365-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen D, O’Rourke JG, Meera P, Muhammad AK, Grant S, Simpkinson M, Bell S, Carmona S, Ornelas L, Sahabian A, et al. Targeting RNA foci in iPSC-derived motor neurons from ALS patients with a C9ORF72 repeat expansion. Science translational medicine. 2013;5:208ra149. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schludi MH, May S, Grasser FA, Rentzsch K, Kremmer E, Kupper C, Klopstock T, Arzberger T, et al. German Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar D , Bavarian Brain Banking A. Distribution of dipeptide repeat proteins in cellular models and C9orf72 mutation cases suggests link to transcriptional silencing. Acta neuropathologica. 2015;130:537–555. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1450-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Rakoczy S, Brown-Borg H. Assessment of spatial memory in mice. Life sciences. 2010;87:521–536. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Miller TM, Yamanaka K, Monia BP, Condon TP, Hung G, Lobsiger CS, Ward CM, McAlonis-Downes M, Wei H, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy for neurodegenerative disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:2290–2296. doi: 10.1172/JCI25424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Zhang Y, Gendron TF, Bauer PO, Chew J, Yang WY, Fostvedt E, Jansen-West K, Belzil VV, Desaro P, et al. Discovery of a biomarker and lead small molecules to target r(GGGGCC)-associated defects in c9FTD/ALS. Neuron. 2014;83:1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Maroof AM, Merkle FT, Koszka K, Intoh A, Armstrong I, Moccia R, Davis-Dusenbery BN, Eggan K. The mouse C9ORF72 ortholog is enriched in neurons known to degenerate in ALS and FTD. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16:1725–1727. doi: 10.1038/nn.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therrien M, Rouleau GA, Dion PA, Parker JA. Deletion of C9ORF72 Results in Motor Neuron Degeneration and Stress Sensitivity in C. elegans. PloS one. 2013;8:e83450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H, Almeida S, Moore J, Gendron TF, Chalasani U, Lu Y, Du X, Nickerson JA, Petrucelli L, Weng Z, et al. Differential Toxicity of Nuclear RNA Foci versus Dipeptide Repeat Proteins in a Drosophila Model of C9ORF72 FTD/ALS. Neuron. 2015;87:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blitterswijk M, DeJesus-Hernandez M, Niemantsverdriet E, Murray ME, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, Brown PH, Baker MC, Finch NA, Bauer PO, et al. Association between repeat sizes and clinical and pathological characteristics in carriers of C9ORF72 repeat expansions (Xpansize-72): a cross-sectional cohort study. Lancet neurology. 2013;12:978–988. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70210-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blitterswijk M, Gendron TF, Baker MC, DeJesus-Hernandez M, Finch NA, Brown PH, Daughrity LM, Murray ME, Heckman MG, Jiang J, et al. Novel clinical associations with specific C9ORF72 transcripts in patients with repeat expansions in C9ORF72. Acta neuropathologica. 2015;130:863–876. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1480-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X, Tan W, Westergard T, Krishnamurthy K, Markandaiah SS, Shi Y, Lin S, Shneider NA, Monaghan J, Pandey UB, et al. Antisense proline-arginine RAN dipeptides linked to C9ORF72-ALS/FTD form toxic nuclear aggregates that initiate in vitro and in vivo neuronal death. Neuron. 2014;84:1213–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler TM, Leger AJ, Pandey SK, MacLeod AR, Nakamori M, Cheng SH, Wentworth BM, Bennett CF, Thornton CA. Targeting nuclear RNA for in vivo correction of myotonic dystrophy. Nature. 2012;488:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature11362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowska M, Krzyzosiak WJ. Cellular toxicity of expanded RNA repeats: focus on RNA foci. Human molecular genetics. 2011;20:3811–3821. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z, Zhang M, Bruni AC, Maletta RG, Colao R, Fratta P, Polke JM, Sweeney MG, Mudanohwo E, Nacmias B, et al. The C9orf72 repeat expansion itself is methylated in ALS and FTLD patients. Acta neuropathologica. 2015;129:715–727. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z, Zinman L, Moreno D, Schymick J, Liang Y, Sato C, Zheng Y, Ghani M, Dib S, Keith J, et al. Hypermethylation of the CpG island near the G4C2 repeat in ALS with a C9orf72 expansion. American journal of human genetics. 2013;92:981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Poidevin M, Li X, Li Y, Shu L, Nelson DL, Li H, Hales CM, Gearing M, Wingo TS, et al. Expanded GGGGCC repeat RNA associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia causes neurodegeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:7778–7783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219643110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Abdallah A, Li Z, Lu Y, Almeida S, Gao FB. FTD/ALS-associated poly(GR) protein impairs the Notch pathway and is recruited by poly(GA) into cytoplasmic inclusions. Acta neuropathologica. 2015;130:525–535. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1448-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Iyer LM, He F, Aravind L. Discovery of Novel DENN Proteins: Implications for the Evolution of Eukaryotic Intracellular Membrane Structures and Human Disease. Frontiers in genetics. 2012;3:283. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Donnelly CJ, Haeusler AR, Grima JC, Machamer JB, Steinwald P, Daley EL, Miller SJ, Cunningham KM, Vidensky S, et al. The C9orf72 repeat expansion disrupts nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature. 2015;525:56–61. doi: 10.1038/nature14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Gendron TF, Grima JC, Sasaguri H, Jansen-West K, Xu YF, Katzman RB, Gass J, Murray ME, Shinohara M, et al. C9ORF72 poly(GA) aggregates sequester and impair HR23 and nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins. Nature neuroscience. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nn.4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Jansen-West K, Xu YF, Gendron TF, Bieniek KF, Lin WL, Sasaguri H, Caulfield T, Hubbard J, Daughrity L, et al. Aggregation-prone c9FTD/ALS poly(GA) RAN-translated proteins cause neurotoxicity by inducing ER stress. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;128:505–524. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1336-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu T, Gibbens B, Doty NS, Gomes-Pereira M, Huguet A, Stone MD, Margolis J, Peterson M, Markowski TW, Ingram MA, et al. Non-ATG-initiated translation directed by microsatellite expansions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:260–265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013343108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu T, Liu Y, Banez-Coronel M, Reid T, Pletnikova O, Lewis J, Miller TM, Harms MB, Falchook AE, Subramony SH, et al. RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:E4968–4977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315438110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.