Abstract

Although yoga has been shown to be a viable technique for improving the performance of the mind and body, little attention has been directed to studying the relationship between yoga and the psychological states of flow and mindfulness. Musicians enrolled in a 2-month fellowship program in 2005, 2006 and 2007 were invited to participate in a yoga and meditation program. Fellows not participating in the yoga program were recruited separately as controls. All participants completed baseline and end-program questionnaires evaluating dispositional flow, mindfulness, confusion, and music performance anxiety. Compared to controls, yoga participants reported significant decreases in confusion and increases in dispositional flow. Yoga participants in the 2006 sample also reported significant increases in the mindfulness subscale of awareness. Correlational analyses revealed that increases in participants' dispositional flow and mindfulness scores were associated with decreases in confusion and music performance anxiety. This study demonstrates the commonalities between positive psychology and yoga, both of which are focused on enhancing human performance and promoting beneficial psychological states. The results suggest that yoga and meditation may enhance the states of flow and mindful awareness, and reduce confusion.

Keywords: music, flow, mindfulness, yoga, meditation

Introduction

Yoga is an ancient mind-body practice that typically consists of breathing exercises, body postures and meditation (Ospina et al., 2007), the original goal of which was to promote higher states of consciousness (Bonura, 2011). Positive psychology, which focuses on the study of human growth and potential, shares several similarities with the underlying principles of yoga as a behavioral practice to enhance human performance and experience. The present study aims to examine the role of yoga in facilitating positive psychological states, namely psychological flow and mindfulness, particularly during music performance.

Psychological Flow

The major focus of positive psychology involves the study of positive emotions, human character (traits and virtues), and positive institutions (Seligman, 2002). In his revised version of the wellbeing theory, Seligman (2011) introduced the PERMA model, which summarizes five pillars of wellbeing (positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment). The PERMA model equates engagement with the state of flow, a construct that was originally introduced by Csikszentmihalyi (1990) and that refers to a very rewarding and enjoyable psychological state in which an individual is completely immersed in an activity such that no attention or “psychic energy” is left for any distractions. The prerequisite condition for entering into a flow state is an optimum balance between the challenge(s) offered by the activity and the skill(s) possessed by the individual (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002; Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2009). Nakamura and Csikszentmihaly (2002; 2009) identified eight discrete phenomenological characteristics that lead to a perfect match between the skill(s) of the individual and the challenge(s) of the activity. To meet this criterion the activity must involve: achievable challenge, immersive potential for attention, clear goals, clear self-evaluative feedback for performance assessment, focused attention, autonomy or self-control, muted self-awareness or dissolution of ego, and distorted sense of time (usually time contraction).

Previous research suggests that musical performance may be associated with flow states. For example, Bakker (2005) found that positive occupational resources and training had beneficial effects on matching the skills and challenges of music teachers thereby resulting in increased experiences of flow. De Manzano et al. (2010) used piano playing as a flow inducing behavior and found that higher self-reported levels of flow were associated with decreased heart period and respiratory sinus arrhythmia as well as increased respiratory depth. MacDonald et al. (2006) found a positive link between music students' reports of creativity and flow, and experts' assessments of the quality of their music performance. In a longitudinal study of student musicians, Fullagar et al. (2013) found that high skill and high challenge increased flow and reduced music performance anxiety (MPA) whereas low skill and high challenge decreased flow and increased MPA. Similarly, Wrigley et al. (2013) found that students who did not believe they were sufficiently skilled to meet the challenge of a music performance reported low levels of flow during the performance.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness has been defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, p. 4). In the practice of yoga, mindfulness is often referred to as awareness. According to Kabat-Zinn (2003), mindfulness meditation practitioners tune into an awareness of the present moment by tuning out thoughts about the past and future. However, mindfulness does not exclude remembering and planning from the human experience. Instead, it aims to free attention from remembering and planning in order to focus awareness on the present moment. The three key elements of mindfulness may be summarized as follows: 1) Ability to pay attention to the present moment (Kabat-Zinn, 2003); 2) Ability to recognize and accurately classify emotions (Analayo, 2003); 3) Ability to experience more refined self-awareness of the present (Kabat-Zinn, 2003).

Although mindfulness is not an explicit part of the PERMA model (Seligman, 2011), there has been discussion in the literature about the overlapping nature of mindfulness and flow states (Siegel, 2009). In particular, flow has been described as a state that emerges from the moment-to-moment experience of mindfulness (Siegel, 2009). Thus, it could be argued that mindfulness may be an implicit aspect of the PERMA model. In addition, previous research suggests several associations between mindfulness and musicology. For example, in a review of 27 publications related to mindfulness and music, Rodríguez-Carvajal and de la Cruz (2014) suggest that mindfulness-based interventions show promise for reducing music performance anxiety. Rodríguez-Carvajal and de la Cruz also propose that listening to music may induce mindful mental states, and that mindfulness inductions may enhance attention and concentration in audiences.

Yoga and Positive Psychological States

Both yoga and positive psychology focus on transforming ordinary existence into a richer and more meaningful life that includes higher levels of subjective wellbeing and even transcendental or spiritual experiences. The main desired outcome of the PERMA model is subjective wellbeing, and prior research provides many examples that discuss the direct relationship between yoga and subjective wellbeing (Jadhav & Havalappanavar, 2009; Lee, 2004; Noggle, Steiner, Minami, & Khalsa, 2012). However, other than one book comparing yoga with positive psychology (Levine, 2009), the joint discussion of these two topics is limited in the literature.

In addition, although flow has been studied among athletes (Wesson & Boniwell, 2007), academics (Beard, 2009; Bernier et al., 2009; De Petrillo et al., 2009; Fullagar & Kelloway, 2009; Jackson & Eklund, 2002; Rogatko, 2009), employees (Demerouti, 2006; Maeran & Cangiano, 2013) and musicians (Bakker, 2005; de Manzano et al., 2010; Fullagar et al., 2013; MacDonald et al., 2006; Wrigley & Emmerson, 2013), studies on the flow experiences of yoga practitioners are rather uncommon. A relatively recent study by Philips (2007) examined the flow experiences of 127 experienced adult ashtanga yoga practitioners. Participants reported experiencing flow during ashtanga yoga, and participants' yoga flow scores were significantly higher than flow scores associated with a comparison “other” physical activity participated in currently or in the past.

Research on the experience of mindfulness during yoga is also relatively uncommon, however initial studies suggest that these two practices are related. For example, Shelov et al. (2009) conducted a pilot study on 46 randomly assigned participants who either underwent an 8-week yoga intervention or participated in a control group. The results showed a significant increase in overall mindfulness and in three subscales of mindfulness in the yoga group. In another study of an 8-week yoga intervention on a sample of 70 staff members of a medical school campus, the yoga group experienced a significant increase in mindfulness (Shelov, 2010). Finally, Brisbon and Lowery (2011) studied the impact of Hatha yoga on 52 participants and found yoga to be an effective technique for enhancing mindfulness. In summary, these studies suggest that yoga provides a means of practicing “mindfulness in motion.”

Purpose of the Present Study

Prior research suggests that mind-body interventions such as yoga may be related to an alleviation of negative psychological states in musicians, such as reduced music performance anxiety (Khalsa, Butzer, Shorter, Reinhardt, & Cope, 2013; Khalsa & Cope, 2006; Khalsa, Shorter, Cope, Wyshak, & Sklar, 2009). The present study expands upon this work by examining whether a yoga intervention might induce the positive psychological states of flow and mindfulness in young adult musicians, as well as whether these positive states are associated with decreases in confusion and performance anxiety. This study is novel in that it examines the relationship between yoga and positive psychology, both of which offer specific strategies that can be practiced to optimize personal wellbeing and performance.

Method

Participants

Participants were part of a prestigious yearly summer fellowship program at the Tanglewood Music Center in 2005, 2006, and 2007. The Tanglewood Music Center is the Boston Symphony Orchestra's academy for high-level musical study, and the 8-week residential program provides outstanding musicians the opportunity to work with globally renowned artists, including members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, resident faculty, and guests. A limited number of fellows are inducted into the program through a very competitive application procedure that includes auditions held in major cities throughout North America.

The teaching faculty of the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health (KCYH), which is in close proximity to the Tanglewood Music Center, partnered with the Tanglewood Institute to offer summer fellows the opportunity for no-cost participation in KCYH yoga classes. Recruitment and remuneration procedures varied slightly from year to year (see Figure 1 for a summary of participant recruitment across all 3 years). In 2005, fellows were required to complete an application outlining their interest in participating in the yoga program. Due to budgetary constraints, the KCYH was able to offer participation to 10 fellows out of a pool of 25 applicants (the 10 fellows were selected based on the quality of their applications). In order to provide a comparison control group, the remaining 15 fellows were queried via email regarding whether they would be willing to participate in the control group, and 10 participants were recruited for the control group from this email on a first-come, first-served basis. The yoga participants were not remunerated for participation, whereas the control participants were remunerated with two free meals at the KCYH over the course of the summer.

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment in 2005, 2006, and 2007.

In 2006, fellows were invited via an email announcement to participate in KCYH yoga and meditation programs at no cost. Thirty-one fellows volunteered to participate. These volunteers were randomized into two yoga intervention groups (n = 15 each), described below, with the one remaining fellow assigned to the control group. In order to recruit additional participants for the control group, a second email announcement was sent several days later to the remaining fellows who had not already volunteered to participate in the yoga group, from which 14 control group participants were recruited on a first-come, first-served basis (n = 15 total in the control group). Yoga participants were not remunerated, however control participants were remunerated with a free massage at the KCYH (valued at $75).

In 2007, fellows were required to complete an application outlining their interest in participating in the yoga program. Based on budgetary constraints, the KCYH was able to offer participation to 20 fellows out of a pool of 61 applicants (the 20 fellows were selected based on the quality of their applications). In order to provide a comparison control group, the remaining 41 fellows were queried via email regarding whether they would be willing to participate in the control group, and 20 participants were recruited for the control group from this email on a first-come, first-served basis. The yoga participants were not remunerated for participation, whereas the control participants were remunerated with a free massage at the KCYH (valued at $75) and four free meals at the KCYH over the course of the summer.

One control participant in 2005 decided not to participate in the study before the intervention began, and another control participant in 2005 did not complete the end-program questionnaires. For the 2006 cohort, the two yoga groups were combined into one group for analysis purposes based on prior research suggesting that the two interventions were not distinct enough to produce differential effects (Khalsa et al., 2009). This resulted in a total of 60 fellows in the yoga condition across all three years (2005 n = 10; 2006 n = 30; 2007 n = 20) and a total of 43 fellows in the control condition across all three years (2005 n = 8; 2006 n = 15; 2007 n = 20). Fellows were not permitted to participate in the study more than once, thus each year was composed of unique individuals. It was the preference of the Tanglewood music center that random assignment to the yoga vs. control conditions not be employed, because the Tanglewood music center preferred that all students who had a desire to participate in yoga be able to do so. Thus, the current study could not randomly assign participants to the yoga vs. control conditions. The only situation in which random assignment was employed was to the two different yoga conditions in the 2006 sample. The research component of the program was approved by the institutional review board of Brigham and Women's Hospital, and all participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Yoga Program protocol

The KCYH provided the yoga intervention for the present study. The KCYH is located in Lenox, Massachusetts and is a popular residential yoga and spiritual retreat center that offers learning opportunities in yoga and related disciplines. Kripalu Yoga is a well-known style of yoga in the U.S. that involves traditional yoga postures, breathing techniques, and meditation and is taught in centers across the country. The yoga intervention was implemented in a very similar manner in 2005, 2006, and 2007, however there were some slight differences, which are described in more detail below (see Table 1 for a summary of the yoga intervention across all 3 years). Across all 3 years, control group participants completed questionnaires before and after the 8-week yoga intervention, however control participants did not take part in any yoga or meditation activities at the KCYH or Tanglewood for the duration of the study.

Table 1.

Yoga Intervention Components By Year.

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Yoga Only | Yoga Lifestyle | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Intervention Length | 8 Weeks | 8 Weeks | 8 Weeks | 8 Weeks |

| One-Day Orientation Program | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Two-Day Orientation Program | ✓ | |||

| Daily 1.25-hour Kripalu yoga classes (3 classes/week recommended) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 30-minute meditation sessions held 5 days/week (participants determined how many sessions to attend) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Weekly 90-minute intensive yoga session followed by 1- to 2-hour group discussion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 60-minute private yoga session | Invited, but not required | ✓ | ||

| Meals at KCYH | ✓ | |||

| One-Day End-Program Retreat | ✓ | |||

2005

In 2005, the selected yoga group fellows started the program with a daylong orientation that covered introductions, goals and intentions of the program, the theory and practice of yoga, two yoga practice sessions, and an introduction to meditation. During the 8-week Kripalu program the yoga participants were offered the following activities:

Daily morning and afternoon Kripalu yoga sessions of low, medium or high intensity. Classes were approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes in length. The fellows were allowed to determine their own yoga class attendance schedule.

Optional attendance in 30-minute mediation sessions held 5 days/week.

One weekly 90-minute intensive yoga evening session facilitated by a senior yoga instructor with previous training in counseling and psychotherapy. This session was followed by a 2 hour discussion on problem solving strategies, group discussions related to the practice of yoga and meditation, status of progression in the music program and psychological issues related to music performance.

Meals in the dining facility of the KCYH. At the end of the program the yoga group participants gathered for an all-day retreat that included an overnight stay in the KCYH dormitories, a yoga class, a group meal and other social activities (see Khalsa & Cope, 2006 for a more detailed description of the 2005 intervention).

2006

In 2006, participants in both yoga intervention groups were offered three 1.25-hour yoga and/or meditation classes per week during the 8-week program. The KCYH offered morning, mid-day, and late afternoon classes 7 days per week in gentle, moderate, or vigorous physical intensity levels, and participants could attend any of these classes. Morning meditation classes were also offered 5 days per week at the Tanglewood Institute and were available only to study participants who were in the yoga groups. The yoga lifestyle intervention group featured a number of additional learning and practice opportunities that were not available to the “yoga only” participants. Similar to the 2005 intervention, the yoga lifestyle group participated in a 2-day intensive retreat at the beginning of the program. The yoga lifestyle group also attended 6 weekly problem-solving group discussions (45 minutes to 1 hour each), which were followed by a 90-minute yoga practice. Finally, yoga lifestyle participants were required to undergo a 60-minute session of private yoga instruction with one instructor to individually address their questions and concerns about yoga postures, breath control, and meditation. Participants in the yoga only group were invited, but not required, to schedule a private instruction session as well (see Khalsa et al., 2009 for a more detailed description of the 2006intervention).

2007

The yoga protocol in 2007 was very similar to the procedures that were followed in prior years. In particular, the 2007 protocol began with a one-day introductory retreat for the yoga group. Yoga group participants were also offered three 1.25-hour yoga and/or meditation classes per week at the KCYH during the 8-week program. Optional 30-minute morning meditation classes were offered 5 days per week at the Tanglewood Institute and were available only to study participants who were in the yoga group. Yoga group participants also took part in a weekly 1-hour problem-solving group discussion followed by a yoga class (as described above).

Outcome Measures

A number of outcome measures were collected across all three years of the present study, however, for the purpose of the current paper we specifically focus on the measures that evaluated positive psychological states that are considered important for music performance, namely psychological flow and mindfulness (see Khalsa & Cope, 2006; Khalsa et al., 2009 for results pertaining to the additional outcome measures).1

The Dispositional Flow Scale (DFS-2)

The DFS-2 is a 36-item questionnaire in which each item is a statement of an experience/feeling of the flow experience (Jackson & Eklund, 2002). All study participants across all 3 years completed this questionnaire once at baseline and once at the end of the yoga program. The scale evaluates nine components of flow: challenge-skill balance (a sense that the challenge at hand matches one's abilities), action-awareness merging (action feels spontaneous and automatic), clear goals (feeling certain about what one is about to do), unambiguous feedback (immediate and clear feedback about one's actions), concentration on the task at hand (being intensely focused on what one is doing in the present moment), sense of control (feeling that one can handle the situation because one knows how to respond to what happens next), loss of self-consciousness (lack of social worry/concern), transformation of time (feeling that the way time passes is distorted) and autotelic experience (experiencing the activity as intrinsically rewarding) (Kawabata & Mallett, 2012). Each question is rated on a scale ranging from 1-5 (1=Never, 5=Always), which represents the frequency of

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

The FFMQ is a well-established 39-item scale for the assessment of mindfulness (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006). Participants in the 2006 and 2007 cohorts completed this questionnaire once at baseline and once at the end of the yoga program. The FFMQ has been shown to assess five distinct facets of mindfulness: observing (noticing/attending to sensations, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings), describing (ability to label feelings, sensations, perceptions and thoughts using words), awareness (ability to act with awareness, concentrate, and avoid distraction), non-judgment of experience (ability to witness sensations, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings non-judgmentally), and non-reactivity to inner experience (ability to witness thoughts and feelings without reacting negatively) (Baer et al., 2006). Each question is answered on a scale ranging from 1-5 (1=never or very rarely true, 5=very often or always true), with higher scores being indicative of higher levels of mindfulness. The questionnaire provides a total mindfulness score as well as scores on each of the five subscales. The range of possible score values on the observing, describing, awareness, and non-judgment subscales is 8 to 40, whereas the range of possible values on the non-reactivity subscale is 7 to 35. The range of possible values on the FFMQ total score is 39 to 195. The FFMQ displays high reliability as well as convergent and discriminant validity (Baer et al., 2006; Baer et al., 2008).

The Profile of Mood States (POMS)

The POMS is a well-tested and broadly used questionnaire that includes 65 affect adjectives that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely). Participants in the 2005 and 2006 cohorts completed the 65-item version of this questionnaire at baseline and at end program, whereas participants in the 2007 cohort completed the POMS Brief, which is a 30-item version of the original POMS. Both scales provide a total mood disturbance score and subscale scores for six mood states: tension/anxiety, depression/dejection, anger/hostility, vigor/activity, fatigue/inertia, and confusion/bewilderment (McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1992). In this study we report only the results from the confusion subscale, as this subscale most directly bears on a performance activity (results for the other subscales can be found in Khalsa & Cope, 2006; Khalsa et al., 2009). The range of possible score values on the confusion subscale on the 65-item POMS is 0 to 28, whereas the range of possible values on the confusion subscale on the 30-item POMS is 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating higher levels of confusion. The POMS has been normed on a wide range of populations and displays high internal consistency and divergent validity (McNair et al., 1992).

The Performance Anxiety Questionnaire (PAQ)

On this 60-item questionnaire, participants were asked to rate the frequency with which they experienced 20 common cognitive and somatic performance anxiety symptoms in three music contexts: (1) practice, (2) group performance, and (3) solo performance. All study participants across all three years completed this questionnaire once at baseline and once at the end of the program. Sample items included: “I feel that I lack confidence” and “I find that I shake.” Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale (1 = never; 5 = always), with higher scores indicating greater performance anxiety. The range of possible score values on all three of the PAQ subscales is 20 to 100. This questionnaire displays excellent construct validity, and a growing literature exists on the use of this measure (Cox & Kenardy, 1993; Fehm & Schmidt, 2006; Kenny, Davis, & Oates, 2004).

Data Analysis

Independent-samples t-tests were used to examine whether there was equivalence between the yoga and control groups at baseline. Given baseline equivalence between groups, analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) with condition (yoga; control) and year (2005; 2006; 2007) as between-subjects factors, and baseline scores as a covariate, were conducted to examine whether end-program scores in psychological flow, mindfulness, and confusion differed significantly between participants in the yoga and control groups across all three years. In addition, in order to examine potential associations between changes in the positive psychological states of flow and mindfulness, and the negative psychological states of confusion and music performance anxiety, Pearson's product-moment correlations were conducted on the difference scores (end-program minus baseline) for the yoga and control groups (see Khalsa & Cope, 2006; Khalsa et al., 2009 for results pertaining to pre- to post-intervention differences between groups on the PAQ and POMS total mood disturbance). The alpha level used to determine significance was p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results Participant Demographics

The total sample in the yoga group across all three years included 25 males and 35 females, with an average age of 25.2 years (SD = 3.2). The total sample in the control group across all three years included 21 males and 22 females, with an average age of 23.6 years (SD = 2.3). The racial/ethnic breakdown in the yoga group across all three years was: 80% White, 3% Black/African American, 15% Asian, and 2% unknown. The racial/ethnic breakdown in the control group across all three years was: 82% White, 2% Black/African American, and 16% Asian.

ANCOVA Analyses

No statistically significant baseline differences were detected between groups. Therefore, Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) between groups with baseline scores as a covariate were conducted on end-program scores. Means, standard deviations and ANCOVA results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Mean Scores for Dispositional Flow, Mindfulness, and Confusion Before and After the Yoga Program.

| Scale | Construct | Yoga | Control | F-Statistic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Condition | Year | Interaction | ||

|

|

||||||||

| DFS-2 | Challenge | 15.72±2.17 | 16.19±2.20 | 16.36±2.77 | 16.33±2.84 | 0.17 | 1.05 | 0.48 |

| Merging | 12.49±2.45 | 13.12±2.70 | 13.44±2.40 | 13.34±2.81 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.22 | |

| Clear Goals | 15.72±2.20 | 16.32±2.36 | 16.28±2.55 | 16.10±2.69 | 1.07 | 0.49 | 0.41 | |

| Unambiguous Feedback | 14.76±2.38 | 15.32±2.64 | 14.79±3.42 | 14.19±3.92 | 3.79t | 1.07 | 0.92 | |

| Concentration | 13.42±2.76 | 14.14±2.54 | 13.72±2.43 | 13.43±2.67 | 1.67 | 0.05 | 0.89 | |

| Control | 13.46±2.62 | 14.51±2.34 | 13.84±2.91 | 14.01±3.24 | 1.79 | 1.27 | 0.47 | |

| Loss of Self-Consciousness | 10.34±2.86 | 12.05±2.92 | 10.67±3.19 | 11.28±3.82 | 1.66 | 1.06 | 0.40 | |

| Transformation of Time | 13.29±2.67 | 13.71±2.95 | 12.09±3.72 | 12.10±3.29 | 1.42 | 0.39 | 0.50 | |

| Autotelic | 15.76±1.88 | 16.25±2.08 | 15.74±2.60 | 15.49±3.02 | 1.94 | 2.44 | 2.86 | |

| Experience Total Flow | 124.96±13. 21 | 131.61±14. 45 | 126.94±14. 41 | 126.25±18. 67 | 4.51* | 1.36 | 0.90 | |

| FFMQ | Observing | 28.90±4.99 | 28.75±5.56 | 27.60±4.86 | 26.00±5.99 | 3.29 | 4.44 * | 1.51 |

| Describing | 26.41±6.80 | 28.19±6.14 | 28.86±6.10 | 30.11±6.86 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Awareness (All Years) | 26.76±4.22 | 28.54±4.39 | 27.29±5.43 | 27.16±5.43 | 3.50 | 2.66 | 6.42* | |

| 26.20±4.04 | 28.43±4.56 | 27.40±6.35 | 25.80±6.37 | 8.94** | n/a | n/a | ||

| Awareness (2006) | ||||||||

| 27.60±4.44 | 28.70±4.22 | 27.20±4.80 | 28.35±4.29 | 0.20 | n/a | n/a | ||

| Awareness (2007) | ||||||||

| Non-Judging | 25.50±7.70 | 28.76±7.47 | 26.80±6.52 | 27.69±7.96 | 1.84 | 0.11 | 0.61 | |

| Non-Reacting | 21.28±3.62 | 21.65±3.28 | 21.31±4.06 | 21.22±3.70 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.00 | |

| Total Mindfulness | 128.85±14.01 | 135.89±15. 66 | 131.86±18.74 | 132.17±20.50 | 3.68 | 1.04 | 1.88 | |

| POMS | Confusion | 10.00±4.62 | 7.27±3.26 | 8.22±5.46 | 8.80±5.39 | 4.24* | 0.41 | 0.43 |

Note: DFS-2 = Dispositional Flow Scale; FFMQ = Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; POMS = Profile of Mood States; n/a = Not Applicable. Means are displayed separately by year for situations in which the results were different between years. t =

p = 0.05;

= p < 0.05;

= p < 0.01.

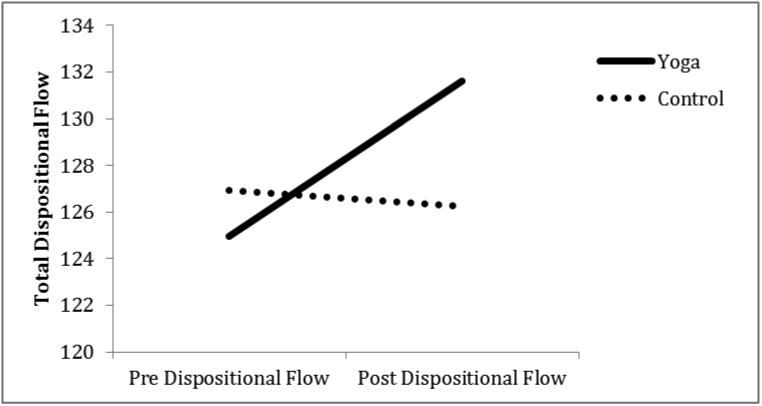

Flow

Total dispositional flow (based on the global DFS-2 score) significantly improved following yoga compared with participants in the control group (see Figure 2). There was a similar trend that approached statistical significance for the Unambiguous Feedback subscale (p = 0.05), however this trend did not reach statistical significance (see Figure 3). The other DFS-2 subscales were not significantly different between groups: autotelic experience, achievable challenge, action-awareness merging, clear goals, concentration, sense of control, loss of self-consciousness, and transformation of time.

Figure 2.

Baseline and end-program scores on total dispositional flow (global DFS-2 score) (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Baseline and end-program scores on the unambiguous feedback subscale of the DFS-2 (p = 0.05).

Mindfulness

A significant main effect of year emerged for the observing subscale suggesting that, regardless of condition, participants in the 2007 sample reported higher end-program observing (M = 28.35) than participants in the 2006 sample (M = 26.72). In addition, the 2-way interaction between condition and year was statistically significant for the awareness subscale. Post-hoc ANCOVAs conducted separately for each year revealed that in 2006, awareness significantly improved following yoga compared with participants in the control group (see Figure 4), however end-program awareness was not significantly different between groups in 2007 (participants in the 2005 sample did not complete the FFMQ). The other FFMQ subscales were not significantly different between groups: describing, non-judging, non-reacting, and total FFMQ.

Figure 4.

Baseline and end-program scores on the awareness subscale of the FFMQ in 2006 (p < 0.05).

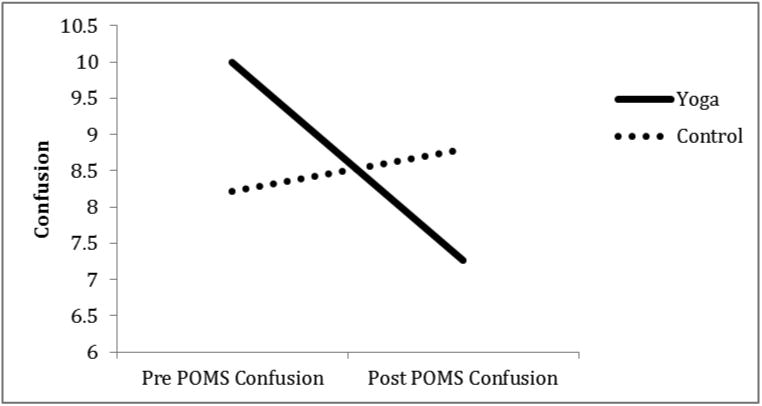

Confusion

Confusion (based on the confusion subscale of the POMS) significantly decreased following yoga compared to participants in the control group (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Baseline and end-program scores on the profile of mood states (POMS) confusion subscale (p < 0.05).

Correlational Analyses

Correlational analyses on the difference scores (end-program minus baseline) for the combined yoga and control groups revealed that increases in participants' total dispositional flow and total mindfulness scores were associated with significant decreases in music performance anxiety (based on the PAQ) in practice (r = -0.40, -0.26, respectively), group (r = -0.44, -0.35, respectively) and solo performance contexts (r = -0.51, -0.36, respectively). Increases in total mindfulness were also associated with significant decreases in confusion (based on the POMS) (r = -0.53). A similar pattern of significant correlations emerged for several of the dispositional flow (DFS-2) and mindfulness (FFMQ) questionnaire subscales in which increasing levels of flow and mindfulness were associated with decreasing levels of confusion and music performance anxiety (see Table 3).

Table 3. Intercorrelations Between Difference Scores for Dispositional Flow, Mindfulness, Confusion, and Music Performance Anxiety.

| DFS-2 | PAQ Practice | PAQ Group | PAQ Solo | POMS Confusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Challenge | -0.32** | -0.33** | -0.27** | -0.05 |

| Merging | -0.38** | -0.32** | -0.41** | -0.01 |

| Clear Goals | -0.22* | -0.18z | -0.21* | -0.18 |

| Unambiguous | -0.06 | -0.08 | -0.21* | -0.07 |

| Feedback | ||||

| Concentration | -0.20 | -0.28** | -0.33** | -0.23 |

| Control | -0.35** | -0.40** | -0.40** | -0.31* |

| Loss of Self- | -0.31** | -0.38** | -0.38** | -0.18 |

| Consciousness | ||||

| Transformation of | -0.03 | -0.03 | -0.09 | -0.15 |

| Time | ||||

| Autotelic Experience | -0.25* | -0.26** | -0.29** | -0.09 |

| Total Flow | -0.40** | -0.44** | -0.51** | -0.25 |

| FFMQ | ||||

| Observing | -0.07 | -0.10 | -0.10 | -0.47** |

| Describing | -0.10 | -0.33** | -0.23* | -0.33* |

| Awareness | -0.20 | -0.30** | -0.30** | -0.47** |

| Non-Judging | -0.24* | -0.20 | -0.21 | -0.23 |

| Non-Reacting | -0.14 | -0.10 | -0.21 | -0.27 |

| Total Mindfulness | -0.26* | -0.35** | -0.36** | -0.53** |

Note: All correlations are between difference scores (end-program minus baseline) for all participants (combined yoga and control groups) across all years (2005, 2006, 2007).

DFS-2 = Dispositional Flow Scale; FFMQ = Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; POMS = Profile of Mood States; PAQ = Performance Anxiety Questionnaire.

= p < .05;

= p < .01.

Discussion

The present findings, namely that participation in yoga may increase several aspects of flow and mindful awareness, are consistent with prior research and theory on positive psychology, yoga philosophy/psychology, and the concepts of flow and mindfulness. In particular, yoga, flow, and mindfulness all share a common emphasis on the mental state of focused attention/awareness and the experience of an absorptive state. In the case of mindfulness, mental focus is directed on the nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment, while psychological flow involves the achievement of a state that is mindful. Flow and mindfulness are essential experiences that are the goals of yoga practice. In other words, yoga is a practice in which one attempts to optimize psychological and physiological states that serve as a vehicle for the expression of contemplative experiences such as flow and mindfulness. This is in agreement with literature suggesting that yoga and mindfulness are coupled states such that an increase in one leads to an increase in the other (Siegel, 2009), as well as previous research showing that participation in yoga can enhance mindfulness (Brisbon & Lowery, 2011; Shelov et al., 2009; Shelov, 2010). The current findings are also congruent with prior work suggesting that yoga experience is related to flow states (Phillips, 2007).

In addition, increases in flow and mindfulness were associated with decreases in music performance anxiety (MPA) in the present study; however the directionality of this relationship is currently unknown. Previous research has found that yoga can alleviate MPA (Khalsa & Cope, 2006; Khalsa et al., 2009; Khalsa et al., 2013; Stern, Khalsa, & Hofmann, 2012). Prior work also suggests that increases in mindfulness and flow are associated with decreased levels of MPA (Kirchner, Bloom, & Skutnick-Henley, 2008; Lin, Chang, Zemon, & Midlarsky, 2008; Oyan, 2006). Thus, it could be the case that yoga induces positive psychological states such as flow and mindfulness, which may, in turn, reduce MPA and enhance music performance. On the other hand, it could be the case that yoga first reduces MPA, which facilitates the manifestation of flow and mindfulness, which then leads to enhanced music performance. Future research should examine these possibilities.

In summary, there is very limited literature available on the effects of yoga on psychological flow and mindfulness; however the few studies that exist appear to be in agreement with the present findings. The current study is a step forward in this area in that it attempts to understand the effects of yoga not only on mindfulness but also on psychological flow, as well as the relationship between these positive psychological states and music performance anxiety.

Limitations

It is important to note several limitations of this study. First, the assignment to the control and yoga groups was not random and thus may have influenced the characteristics of the yoga subjects in a direction favorable to a positive outcome. In particular, participants in the yoga program were highly motivated to undergo the yoga intervention and it is possible that an expectation of performance enhancement may have contributed to their perceived benefit. It is also possible that participants in the control group may have engaged in activities throughout the duration of the study that could have benefited them, as control subjects were not given any instruction with regard to participating in or avoiding any particular types of activities. In addition, several of the differences that were found between the yoga and control groups, while statistically significant, were relatively small in magnitude. To our knowledge, norms have not been set regarding what constitutes a clinically meaningful change on the DFS-2 or FFMQ, thus it will be important for future research to examine the practical implications of such findings. Finally, the fact that control participants were remunerated at different rates across all 3 years of the study may have impacted the results. For example, it is possible that control participants who received higher remuneration may have been more motivated to respond positively to the questionnaires. Future research should examine the concepts of yoga, flow, and mindfulness using larger samples in which subjects are randomly assigned to groups.

Implications and Future Research

The associations that were found in the present study between yoga and positive psychological states suggest that yoga may be an effective technique for enhancing performance in multiple contexts, including music performance. For example, it could be the case that, by facilitating positive psychological states such as flow and mindfulness, yoga may also enhance performance in sport, art, business, and academic contexts. Some research is supportive of this idea. For example, several studies have found that yoga enhances cognitive performance, including attention, concentration, and memory (Bhatia et al., 2012; Chaya, Nagendra, Selvam, Kurpad, & Srinivasan, 2012; Nangia & Malhotra, 2012; Prakash et al., 2012; Sahasi, 1984). Studies also suggest that mind-body interventions such as yoga and meditation may improve several aspects of student performance such as academic achievement (Beauchemin, Hutchins, & Patterson, 2008; Benson et al., 2000; Kauts & Sharma, 2009; Nidich et al., 2011; Sibinga et al., 2011) and classroom behavior (Barnes, Bauza, & Treiber, 2003; Koenig, Buckley-Reen, & Garg, 2012; Schonert-Reichl & Lawlor, 2010). However, the present study did not measure performance, thus it is unclear whether the increases in flow and mindfulness that were achieved via yoga would enhance actual music performance. Future research should explore this possibility.

Conclusions

Yoga may be an effective technique for improving flow and mindful awareness and for reducing confusion. In addition, enhanced flow and mindfulness are associated with decreases in confusion and music performance anxiety. A resolution of confusion and music performance anxiety may be instrumental in fostering higher-level psychological characteristics. Future studies should examine whether yoga can enhance these optimal psychological states in other performance contexts.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Institute for Extraordinary Living of the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health as well as the Tanglewood Music Center for supporting this research. We are also grateful for the contributions of Stephen Cope, who was instrumental in organizing and facilitating several aspects of this research across all three years of the program. We acknowledge the contribution of Susan Moul and Nancy Buttenheim who served as instructors of the yoga program in 2005. The contribution of Sat Bir S. Khalsa in 2005 was supported in part by a research career award (K01AT000066) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the NIH. We also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Nancy Buttenheim, Jo Ann Levitt, and Larissa Hall Carlson who served as instructors for the yoga program in 2006, Ann Megyas who assisted many of the yoga and meditation classes in 2006, and Angela Wilson who supervised several aspects of this study in 2006 and 2007. We are also grateful for the contribution of Amanda LoRusso, who assisted with the preparation of this paper for publication.

Sat Bir S. Khalsa has received consultant fees from the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health, and the contribution of Sat Bir S. Khalsa in 2005 was supported in part by a research career award (K01AT000066) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the NIH. Bethany Butzer's contribution to this manuscript was supported by a grant from the Institute for Extraordinary Living of the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health.

Footnotes

Additional outcome measures reported in Khalsa & Cope (2006) and Khalsa et al. (2009) include: The Performance-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Questionnaire (Ackermann, Adams, & Marshall, 2002), the tension, depression, anger, vigor, and fatigue subscales of the Profile of Mood States (McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1992), the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen & Williamson, 1988), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, occurrence of a particular flow construct during the performance of an activity. The scale provides a total flow score as well as a subscale score for each flow construct. The range of possible score values on all nine of the DFS-2 subscales is 4 to 20, whereas the range of possible values on the DFS-2 total flow score is 36 to 180, with higher scores being indicative of greater flow. The DFS-2 displays high reliability and good construct validity (Jackson & Eklund, 2002).

Contributor Information

Bethany Butzer, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School

Khalique Ahmed, Division of Natural and Applied Sciences, Lynn University, Boca Raton, FL.

Sat Bir S. Khalsa, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School

References

- Ackermann B, Adams R, Marshall E. Strength or endurance training for undergraduate music majors at a university? Medical Problems of Performing Artists. 2002;17(1):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Analayo. Satipatthana : The direct path to realization. Windhorse Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Avey JB, Nimnicht JL, et al. Pigeon NG. Two field studies examining the association between positive psychological capital and employee performance. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2010;31(5):384–401. doi: 10.1108/01437731011056425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, et al. Williams JMG. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment. 2008;15(3):329–342. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AB. Flow among music teachers and their students: The crossover of peak experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2005;66(1):26–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes VA, Bauza LB, Treiber FA. Impact of stress reduction on negative school behavior in adolescents. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2003;1(10):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard KLS. An exploratory study of academic optimism and flow of elementary school teachers. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 2009;69(8) 2009-99031-036. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin J, Hutchins TL, Patterson F. Mindfulness meditation may lessen anxiety, promote social skills, and improve academic performance among adolescents with learning disabilities. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2008;13(1):34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Benson H, Wilcher M, Greenberg B, Huggins E, Ennis M, Zuttermeister PC, et al. Friedman R. Academic performance among middle-school students after exposure to a relaxation response curriculum. Journal of Research and Development in Education. 2000;33(3):156. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier M, Thienot E, Codron R, Fournier JF. Mindfulness and acceptance approaches in sport performance. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 2009;3(4):320–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava R, Gogate MG, Mascarenhas JF. Autonomic responses to breath holding and its variations following pranayama. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1988;32(4):257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia T, Agarwal A, Shah G, Wood J, Richard J, Gur RE, et al. Deshpande SN. Adjunctive cognitive remediation for schizophrenia using yoga: An open, non-randomised trial. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2012;24(2):91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2011.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrer D, Röthlin P, Morgan G. Mindfulness to enhance athletic performance: Theoretical considerations and possible impact mechanisms. Mindfulness. 2012;3(3):235–246. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0109-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonura KB. The psychological benefits of yoga practice for older adults: Evidence and guidelines. International Journal of Yoga Therapy. 2011;21:129–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisbon NM, Lowery GA. Mindfulness and levels of stress: A comparison of beginner and advanced hatha yoga practitioners. Journal of Religion and Health. 2011;50(4):931–941. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9305-3;10.1007/s10943-009-9305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry research. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaya MS, Nagendra H, Selvam S, Kurpad A, Srinivasan K. Effect of yoga on cognitive abilities in schoolchildren from a socioeconomically disadvantaged background: A randomized controlled study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2012;18(12):1161–1167. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WJ, Kenardy J. Performance anxiety, social phobia, and setting effects in instrumental music students. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1993;7(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(93)90020-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow : The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, et al. Sheridan JF. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(4):564–570. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DM, Hayes JA. What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0022062;10.1037/a0022062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Manzano O, Theorell T, Harmat L, Ullen F. The psychophysiology of flow during piano playing. Emotion. 2010;10(3):301–311. doi: 10.1037/a0018432;10.1037/a0018432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Petrillo LA, Kaufman KA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB. Mindfulness for long-distance runners: An open trial using mindful sport performance enhancement (MSPE) Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 2009;3(4):357–376. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E. Job characteristics, flow, and performance: The moderating role of conscientiousness. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11(3):266–280. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehm L, Schmidt K. Performance anxiety in gifted adolescent musicians. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20(1):98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullagar CJ, Kelloway EK. ‘Flow’ at work: An experience sampling approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2009;82(3):595–615. doi: 10.1348/096317908X357903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fullagar CJ, Knight PA, Sovern HS. Challenge/skill balance, flow, and performance anxiety. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2013;62(2):236–259. [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JM. Mindfulness research update: 2008. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2009;14(1):10–18. doi: 10.1177/1533210108329862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman G. The musician and the creative process. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis & Dynamic Psychiatry. 2005;33(1):97–117. doi: 10.1521/jaap.33.1.97.65885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner E. Review of ‘applied positive psychology: Improving everyday life, health, schools, work, and society’. The Journal of Social Psychology [Serial Online] 2012;152(1):128–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SA, Eklund RC. Assessing flow in physical activity: The flow state scale-2 and dispositional flow scale-2. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 2002;24(2):133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav SG, Havalappanavar NB. Effect of yoga intervention on anxiety and subjective well-being. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology. 2009;35(1):27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jha AP, Krompinger J, Baime MJ. Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;7(2):109–119. doi: 10.3758/cabn.7.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman KA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB. Evaluation of mindful sport performance enhancement (MSPE): A new approach to promote flow in athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 2009;3(4):334–356. [Google Scholar]

- Kauts A, Sharma N. Effect of yoga on academic performance in relation to stress. International Journal of Yoga. 2009;2(1):39. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.53860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata M, Mallett CJ. Interpreting the dispositional flow scale-2 scores: A pilot study of latent class factor analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2012;30(11):1183–1188. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.695083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DT, Davis P, Oates J. Music performance anxiety and occupational stress amongst opera chorus artists and their relationship with state and trait anxiety and perfectionism. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18(6):757–777. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa SB, Butzer B, Shorter SM, Reinhardt KM, Cope S. Yoga reduces performance anxiety in adolescent musicians. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2013;19(2):34–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa SB, Cope S. Effects of a yoga lifestyle intervention on performance-related characteristics of musicians: A preliminary study. Medical Science Monitor : International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2006;12(8):CR325–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa SB, Shorter SM, Cope S, Wyshak G, Sklar E. Yoga ameliorates performance anxiety and mood disturbance in young professional musicians. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2009;34(4):279–289. doi: 10.1007/s10484-009-9103-4;10.1007/s10484-009-9103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner JM, Bloom AJ, Skutnick-Henley P. The relationship between performance anxiety and flow. Med Probl Perform Art. 2008;23:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig KP, Buckley-Reen A, Garg S. Efficacy of the get ready to learn yoga program among children with autism spectrum disorders: A Pretest–Posttest control group design. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012;66(5):538–546. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2012.004390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar SW. Mindfulness research. In: Germer CK, Siegel RD, Fulton PR, editors. Mindfulness and Psychotherapy. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 220–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lee GW. The subjective well-being of beginning vs. advanced hatha yoga practitioners. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2004;65(4-) 2004-99020-145. [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. The positive psychology of buddhism and yoga: Paths to a mature happiness, with a special application to handling anger. 2nd. New York, NY US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Chen S, Wang R. Savouring and perceived job performance in positive psychology: Moderating role of positive affectivity. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;14(3):165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lin P, Chang J, Zemon V, Midlarsky E. Silent illumination: A study on chan (zen) meditation, anxiety, and musical performance quality. Psychology of Music. 2008;36(2):139–155. doi: 10.1177/0305735607080840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linley P, Joseph S, Maltby J, Harrington S, Wood A. Oxford handbook of positive psychology. 2nd. New York, NY USA: Oxford University Press; 2009. Positive psychology applications; pp. 35–47. e-book. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald R, Byrne C, Carlton L. Creativity and flow in musical composition: An empirical investigation. Psychology of Music. 2006;34(3):292–306. doi: 10.1177/0305735606064838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maeran R, Cangiano F. Flow experience and job characteristics: Analyzing the role of flow in job satisfaction. TPM-Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology. 2013;20(1):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L. Profile of mood states: EdITS manual. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan M, Saravanane C, Surange SG, Thombre DP, Chakrabarty AS. Effect of yoga type breathing on heart rate and cardiac axis of normal subjects. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1986;30(4):334–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek MD, Franklin MS, Phillips DT, Baird B, Schooler JW. Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychological Science. 2013;24(5):776–781. doi: 10.1177/0956797612459659;10.1177/0956797612459659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura J, Csikszentmihalyi M. The concept of flow. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura J, Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow theory and research. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Nangia D, Malhotra R. Yoga, cognition and mental health. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology. 2012;38(2):262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Nidich S, Mjasiri S, Nidich R, Rainforth M, Grant J, Valosek L, et al. Zigler RL. Academic achievement and transcendental meditation: A study with at-risk urban middle school students. Education. 2011;131(3):556–564. [Google Scholar]

- Noggle JJ, Steiner NJ, Minami T, Khalsa SB. Benefits of yoga for psychosocial well-being in a US high school curriculum: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP. 2012;33(3):193–201. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31824afdc4;10.1097/DBP.0b013e31824afdc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ospina MB, Bond K, Karkhaneh M, Tjosvold L, Vandermeer B, Liang Y, et al. Klassen TP. Meditation practices for health: State of the research. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. 2007;155:1–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyan S. Mindfulness meditation: Creative musical performance through awareness. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 2006;67(2-) 2006-99015-113. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LL. Examining flow states and motivational perspectives of ashtanga yoga practitioners. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 67(7-) 2007-99001-124. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash R, Rastogi P, Dubey I, Abhishek P, Chaudhury S, Small B. Long-term concentrative meditation and cognitive performance among older adults. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2012;19(4):479–494. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2011.630932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Carvajal R, de la Cruz OL. Mindfulness and Music: A Promising Subject of an Unmapped Field. Int J Behav Res Psychol. 2014;2(3):27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rogatko TP. The influence of flow on positive affect in college students. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2009;10(2):133–148. doi: 10.1007/s10902-007-9069-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahasi G. A replicated study on the effects of yoga on cognitive functions. Indian Psychological Review. 1984;27(1-4):33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon P, Lush E, Jablonski M, Sephton SE. Yoga and mindfulness: Clinical aspects of an ancient mind/body practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2009;16(1):59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl KA, Lawlor MS. The effects of a mindfulness-based education program on pre-and early adolescents' well-being and social and emotional competence. Mindfulness. 2010;1(3):137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M. Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY: Free Press: A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being (e-book ed) New York, NY: Free Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology an introduction. The American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao R, Skarlicki DP. The role of mindfulness in predicting individual performance. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement. 2009;41(4):195–201. doi: 10.1037/a0015166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelov DV, Suchday S, Friedberg JP. A pilot study measuring the impact of yoga on the trait of mindfulness. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;37(5):595–598. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809990361;10.1017/S1352465809990361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelov DV. The impact of yoga on cardiovascular reactivity, empathy & mindfulness. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2010;70(8-) 2010-99040-352. [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EM, Kerrigan D, Stewart M, Johnson K, Magyari T, Ellen JM. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for urban youth. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2011;17(3):213–218. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RD. The mindfulness solution: Everyday practices for everyday problems. Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stern JR, Khalsa SB, Hofmann SG. A yoga intervention for music performance anxiety in conservatory students. Medical Problems of Performing Artists. 2012;27(3):123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr A. Music and the mind. New York, NY US: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Telles S, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. Breathing through a particular nostril can alter metabolism and autonomic activities. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1994;38(2):133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesson K, Boniwell l. Flow theory--its application to coaching psychology. International Coaching Psychology Review. 2007;2(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley WJ, Emmerson SB. The experience of the flow state in live music performance. Psychology of Music. 2013;41(3):292–305. doi: 10.1177/0305735611425903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]