Abstract

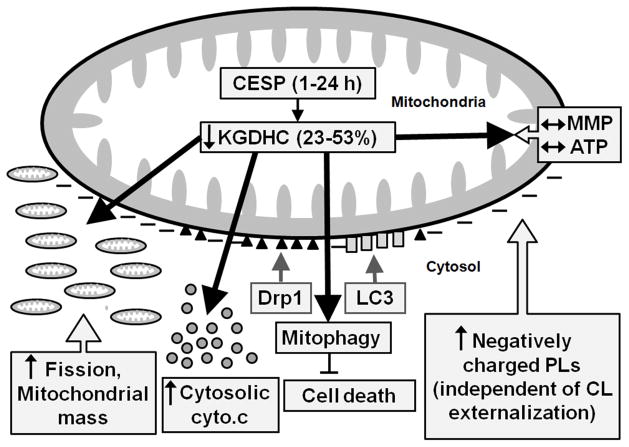

Brain activities of the mitochondrial enzyme α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (KGDHC) are reduced in Alzheimer’s disease and other age-related neurodegenerative disorders. The goal of the present study was to test the consequences of mild impairment of KGDHC on the structure, protein signaling and dynamics (mitophagy, fusion, fission, biogenesis) of the mitochondria. Inhibition of KGDHC reduced its in situ activity by 23–53% in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, but neither altered the mitochondrial membrane potential nor the ATP levels at any tested time-points. The attenuated KGDHC activity increased translocation of dynamin-related protein-1 (Drp1) and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) from the cytosol to the mitochondria, and promoted mitochondrial cytochrome c release. Inhibition of KGDHC also increased the negative surface charges (anionic phospholipids as assessed by Annexin V binding) on the mitochondria. Morphological assessments of the mitochondria revealed increased fission and mitophagy. Taken together, our results suggest the existence of the regulation of the mitochondrial dynamism including fission and fusion by the mitochondrial KGDHC activity via the involvement of the cytosolic and mitochondrial protein signaling molecules. A better understanding of the link among mild impairment of metabolism, induction of mitophagy/autophagy and altered protein signaling will help to identify new mechanisms of neurodegeneration and reveal potential new therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: Mitochondria, autophagy, mitophagy, fission, glucose metabolism, neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

Decreased brain utilization of glucose always accompanies Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and precedes its clinical manifestations by years (Furst et al., 2012). Reductions in the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle enzymes may underlie the decline in glucose metabolism seen in neurodegeneration (Bubber et al., 2005). Diminished activity of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (KGDHC), critical and often rate limiting step of the TCA cycle, has been extensively documented in studies of post-mortem brains from patients with AD (Bubber et al., 2005; Gibson et al., 2005). This reduction is highly correlated to the decline in the clinical dementia rating scale in patients with AD (Bubber et al., 2005). Animal models demonstrate that reducing the activity of KGDHC by one-half diminishes neurogenesis and memory, and stimulates the formation of AD-like pathology, including plaques and tangles (Karuppagounder et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009). KGDHC is a thiamine-dependent enzyme and increasing thiamine largely prevents the AD pathology in a mouse model of AD (Pan et al., 2010).

In addition to their traditional and important role of providing energy, mitochondria are the central regulators in cellular protein signaling pathways. Protein signaling modulates mitochondrial fusion and fission, which are necessary for mitochondrial health (Losón et al., 2013; Youle and van der Bliek, 2012). Metabolically compromised mitochondria split to form smaller, spherical mitochondria by fission. Some of these spherical organelles fuse with healthy mitochondria by the process of fusion. Translocation of the translocation occurs when Drp1 is modified and activated by phosphorylation, SUMOylation, cytosolic GTPase, dynamin-related protein-1 (Drp1), to the mitochondria is the critical step to initiate the mitochondrial fission (Chan, 2006). This ubiquitination, S-nitrosylation or O-linked-N-acetyl glucosamine glycosylation. Activated Drp1 translocates to the mitochondria and assembles into helical structures which subsequently induce fragmentation or fission of the organelles (Cereghetti et al., 2008). Even mild oxidative stress can induce a Drp1-dependent increase in fission which promotes mitophagy (Frank et al., 2012). Drp1 is also involved in mitochondrial cytochrome c release (Estaquier et al., 2007; Kageyama et al., 2014).

Specific mitochondrial protein signaling also modulates autophagy which continuously repairs cells by removing damaged cytosolic components and organelles. Migration of some specific cytosolic proteins is a central part of autophagy that is particularly targeted towards the mitochondria (mitophagy), which in turn influences and promotes the selective survival of the existing healthy mitochondria within the cells (Banerjee et al., 2015; Lemasters et al., 2005). For example: (a) parkin migration to the mitochondria is a common early step in depolarization-induced mitophagy (Vives-Bauza et al., 2010); (b) microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) is a soluble protein which is distributed ubiquitously in mammalian tissues and cultured cells, and upon autophagic activation the cytoplasmic LC3 (LC3I) protein is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine to form the LC3-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate (LC3II) which, in turn, is recruited to autophagosomal membranes (Harris-White et al., 2015); (c) the movement of cardiolipin (CL) from the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) recruits LC3 and induces mitophagy (Chu et al., 2013). Depolarization and increased fission of the mitochondria make the organelles more fragmented and favor their selection for mitophagy. The fragmented and small mitochondria can be easily engulfed by autophagosome / lysosome (Gomes et al., 2013). Damaged mitochondria also release cytochrome c and apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) to the cytosol from the mitochondrial inter membrane space. Cytochrome c activates caspase-dependent apoptosis while, simultaneously, AIF translocates to the nucleus, inducing chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation in a caspase-independent manner, ultimately culminating in cell death (Yu et al., 2002). Cytochrome c released from compromised and stressed mitochondria can induce caspase-dependent apoptosis, though the release of cytochrome c also occurs in the absence of apoptosis (Ghibelli et al., 1999). Release of cytochrome c can induce non-specific autophagy within the cell. Several different mechanisms can trigger the release of cytochrome c: CL peroxidation, leakage through the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore complex, Bax and Bak interactions with voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), and high K+ level in extra-mitochondrial matrix (Gogvadze et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2005).

Since very little is known about the underlying mechanism(s) causing alterations of the cellular functions and the neurodegenerative processes induced by changes in KGDHC activity, a better understanding of these phenomena at the cellular level is required in order to establish the role of KGDHC in the pathophysiology of AD and to identify appropriate novel therapeutic targets. Therefore, in the present study, we examined the consequences of the reduced KGDHC activity on mitochondrial protein signaling using a very specific inhibitor of KGDHC, the carboxy ethyl ester of succinyl phosphonate (CESP) (Bunik et al., 2005) in the human neuroblastoma cell line, SH-SY5Y. We hypothesized that the consequences of mild impairment of KGDHC would be amplified by alterations in protein signaling that control the fusion/fission and mitophagy/autophagy. Our findings suggest the regulation of mitochondrial dynamism by the intracellular KGDHC activity by recruitment of different players of autophagy/mitophagy, and altered protein signaling may be critical in the neurodegenerative process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture

SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator under 5% CO2 and 95% air in equal volumes (1:1) of Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) and F12K supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies, CA, USA). For regular maintenance, cells were grown in 100 mm tissue culture plates. On reaching 70–80% confluence, the cells were trypsinized in 2 ml of 0.05% trypsin-EDTA for 2 min, followed by centrifugation at 200g for 10 min and suspension of the resulting cell-pellet in fresh medium. For subsequent maintenance, the cells were split and 0.5 x 106 viable cells, counted by trypan blue method (Banerjee et al., 2014), were seeded in freshly obtained sterile 100 mm tissue culture plates. The culture medium was changed every 2–3 days. All experiments were done using cells with passage numbers less than 20. Unless otherwise mentioned, all materials for cell culture were obtained from Corning, NY, USA.

2.2. Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibodies used in the study were anti-LC3 (MBL International, MA, USA), anti-translocase of the inner membrane (TIM23 or anti-Tim23, BD Transduction Lab, CA, USA), Parkin (Santa Cruz, TX, USA) and Drp1 (Santa Cruz, TX, USA), while rabbit polyclonal antibodies used were β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA) and cytochrome c (Santa Cruz, TX, USA). Secondary antibodies used were Licor fluorescent antibodies (Licor, NE, USA).

2.3. Cytochemistry assay for measurement of KGDHC activity in SH-SY5Y cells

SH-SY5Y cells were seeded (0.25x105) in 24-well-plates and grown for three days in 1:1 EMEM:F12K medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were rinsed with 1:1 EMEM:F12 media without FBS. Cells were then incubated in the latter media with or without CESP (100 μM) and incubated for 0, 1, 2, 5 or 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were subsequently rinsed once with a buffered balanced salt solution (BSS) and once with BSS containing 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100. Cells were incubated for 1 h in incubation buffer (1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.05 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.3 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 5 μg/ml Rotenone, 35 mg/ml Polyvinyl alcohol, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.6) with (experimental group) or without (blank) α-ketoglutarate (KG) and coenzyme A (CoA) for both the control and the CESP treated groups. The final concentrations are indicated in parentheses: CESP (100 μM), NAD+ (3 mM), KG (3 mM), CoA (1 mM). Cells were incubated for 60 min at 37°C in the same humidified environment mentioned under “Cell culture” section. After the incubation, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), followed by the addition of 200 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 10%) dissolved in 0.001 N HCl and incubated overnight. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured on the following day, and each experimental sample reading was calculated after subtracting the corresponding blank reading (Bunik et al., 2005; Park et al., 2000; Santos et al., 2006).

2.4. Isolation of mitochondrial-cytosolic fraction from SH-SY5Y cells

0.5x106 cells were plated in 100 mm tissue culture plates and grown for three days in 1:1 EMEM:F12K medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were then rinsed with 1:1 EMEM:F12 media without FBS and were subsequently incubated in the latter media with (CESP-treated group) or without (control group) CESP (100 μM) and incubated for 1, 5 and 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator under humidified environment. Cells were harvested and rinsed with PBS before preparation of mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions. Mitochondria were isolated from the control and CESP-treated cells following previously published method (Vives-Bauza et al., 2010) with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were uniformly suspended in mitochondrial isolation buffer (1 mM EGTA, 75 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, 225 mM mannitol, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.04% digitonin, protease inhibitor cocktail-Roche (one tablet per 10 ml buffer) and were homogenized on ice in a type B Dounce glass homogenizer with 40 strokes. Intact cells and nuclei were removed by centrifuging the suspension at 1,500g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were centrifuged at 15,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatants were collected as the cytosolic fractions. The pellets containing mitochondria were collected in isolation buffer without digitonin and BSA. Cytosolic fractions were concentrated using Amicon ultra filters (0.5 ml, 10K, Millipore, MA, USA).

2.5. Protein quantification

The quantity of protein in the mitochondrial and the cytosolic fractions was measured with the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method following kit literature (Pierce, Thermo Scientific, USA).

2.6. Western blot analysis

The mitochondrial and cytosolic samples (30 μl each) were mixed with 6X reducing loading buffer (BP-IIIR, Boston Bioproducts, MA, USA) containing 375 mM Tris HCl (pH 6.8), 6% SDS, 48% glycerol, 9% beta-mercaptoethanol and 0.03% bromophenol, followed by heating the mixture at 95°C for 5 min. Mitochondrial (30–40 μg), cytosolic (30–60 μg) proteins were loaded on to a 4–20% Bis-Tris gel (Life Technologies, NY, USA) and run for 2 –3 h (25 mA, 100V) followed by overnight wet transfer at 30 volts. Blocking was done for 4 h. Primary antibodies were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. TIM23 was used as the mitochondrial marker. β-actin was used as the cytosolic marker. Parkin antibody (1:1,000 dilution), TIM23 antibody (1:5,000 dilution), LC3 antibody (1:1,000 dilution), cytochrome c antibody (1:1,000), and Drp1 antibody (1:1,000) were used at the indicated dilutions. On the following day, β-actin antibody (1:5,000 dilution) was added for one h. The membrane was washed (three times) with washing buffer (1X Tris Buffer Saline, 0.1% Tween-20, Bio-Rad, CA, USA) at room temperature and then incubated with IR dye-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000) at room temperature for 40 min. The bands were visualized and analyzed by the Li-Cor, Odyssey quantitative Western blotting system and application software (Shi et al., 2005). The lysosomal inhibitors (LIs) pepstatin A and E64D were added at 10 μM (Melser et al., 2013) during the incubation of the cells with or without CESP.

2.7. Annexin V binding assay

SH-SY5Y cells were treated with Staurosporine (STS, 1 μM) for 3 h or CESP (100 μM) for 1 h in media without FBS. STS was used as the positive control and the experiments were done exactly as before (Chu et al., 2013). The cells were then treated with mitotracker green (200 nM final concentration; Invitrogen, USA) and kept for 20 min in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Mitochondria were isolated in the same way mentioned before using isolation buffer (210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1X protease cocktail inhibitors (Roche, USA) and fatty acid free BSA). Final mitochondrial pellets were washed and uniformly suspended in wash buffer (isolation buffer without EGTA and BSA). Mitochondrial protein (10 μg) was mixed in wash buffer made with 200 μM CaCl2 in a total volume of 100 μl. Annexin V- Alexa Fluor 647 (5 μl) was added to the mitochondrial suspension for 5 min at room temperature in the dark followed by analysis in a CFlow flow cytometer (BD Accuri C6). 20,000 events were selected for assessing the fluorescence. Only the part that was positive for mitotracker green was selected in the flow cytometer for Annexin V measurement. The cytometer software was used to calculate the percentage increase of Annexin V in CESP treated cells compared to controls (Chu et al., 2013).

2.8.Assessment of mitophagy and mitochondrial morphology

Co-localization of mitochondrial marker (red) with the autophagic marker (green) was used as evidence of mitophagy. Mitotracker red (CMXRos, M7512, Invitrogen, USA) binds with mitochondria and fluoresces red. The Cyto ID kit (Autophagy detection kit, ENZ-51031-K200 Enzo Life Sciences) was used to detect autophagy. Cyto ID green dye specifically binds with autophagic vacuoles and fluoresces green. Mitochondria co-localizing with autophagic vacuoles appear yellow (vander Burgh et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2014). One x 105 cells were seeded onto uncoated 0.17 mm thick (25 mm diameter) clear delta T dishes (Bioptechs Inc, USA) and maintained under the same conditions as mentioned in the “Cell culture” section. After 24 h, the media were replaced with 500 μl of 1:1 EMEM:F12K media without FBS. Cells were treated with CESP (100 μM) for 24 h. After the incubation, the cells were washed twice with media (room temperature) and incubated with 50 nM mitotracker red and one μl cyto ID dye in 500 μl of same media for 30 min in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The cells were then washed three times with PBS and examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Ma et al., 2014) (channel 488 and 570 for green and red respectively) (Carl Zeiss Microimaging). Mitochondrial morphology was assessed after staining with mitotracker red.

Co-localization analysis and automated morphometry of the mitochondria were performed using the ImageJ software and plugins as described before (Li et al., 2004; Merrill et al., 2011) with slight modifications. For quantification of co-localization, ImageJ macros was run and the image under study was processed for the RGB split into binary (black and white) grayscale images by auto-thresholding. Using the selection tools, region of interest (ROI) containing the signal in channel 1 (red) image was selected. The co-localization analysis tool of the same software was used for intensity correlation analysis and co-localization finding (Li et al., 2004). Co-localization of autophagosome with mitochondria was quantified using both the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) and the Mander’s overlap coefficient (MOC) (Adler and Parmryd, 2010; Merrill et al., 2011). Values of PCC range from −1 to +1 while that of MOC from 0 to +1, with higher values indicating greater correlation (Adler and Parmryd, 2010). For automated morphometry, images were analyzed for different morphological parameters of the mitochondria following established methods (Merrill et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2012). Briefly, ImageJ macros was activated followed by processing of the images and selection of the different ROI to convert them into binary (black and white) images by auto-thresholding. Subsequently the software automatically analyzed different mitochondrial parameters. From these values we calculated the aspect ratio and the form factor of the mitochondria in the control and the CESP-treated groups. Aspect ratio has been defined as the ratio between the major and the minor axes of the ellipse equivalent to the mitochondrion (Zhu et al., 2012). An aspect ratio value of 1 indicates a perfect circle and its elevated value indicates elongated mitochondria (Zhu et al., 2012). Form factor has been defined as (perimeter)2 / {4*π*(area)} (Merrill et al., 2011). A minimum of five ROI from three independent experiments were analyzed for the co-localization and morphometric studies.

2.9. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

MMP was measured with a cell permeable, cationic red-orange fluorescent dye, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) following a standardized method in our lab (Huang et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2001). TMRM is readily sequestered by metabolically active mitochondria in an MMP-dependent manner. Briefly, SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in Delta TPG dishes at the seeding density of 2 x 104 cells / dish and grown for 2 days (1:1 EMEM:F12 with 10 % FBS). Cells were rinsed with 1:1 EMEM:F12 media without FBS. Cells were then treated in the latter media with or without CESP (100 μM) and incubated for 0, 1, 5 or 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After the treatment, the cells were rinsed with BSS once and loaded with 20 nM TMRM for 40 min at 37°C. Fluorescence images were obtained with excitation at 540 nm and emission at 590 nm on the stage of an inverted Olympus IX70 microscope at 37°C with a Delta Scan System from PTI (Photon Technology International, NJ, USA).

2.10. Measurement of ATP concentration

Mitochondrial ATP level was measured by the luciferin-luciferase bioluminescence assay using an ATP determination kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). SH-SY5Y cells were seeded and treated with CESP (100 μM) for 0, 1, 5 or 24 h in 6-well plates. After the treatment, the cells were rinsed with cold PBS once and harvested with centrifuging the suspension at 1,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and resuspended with lysate buffer (1 mM DTT, 0.4% Triton X-100, 1mM EGTA, 50 mM Tris; pH 7.6). ATP content was determined by the luciferin-luciferase bioluminescence assay kit following the kit literature.

2.11. Measurement of cell death and cell viability

2.11.1. Trypan blue method

An equal volume of 0.4% (w/v) trypan blue solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was added to the cell suspension for 2 min and the numbers of stained and unstained cells were counted under the phase contrast light microscope by an observer blind to the experimental treatment conditions of the cells (i.e. whether control or CESP-treated). Typically, 100–200 cells were counted in each group with a Neubauer counting chamber by an observer blind to the experimental history. The cell death was expressed as the percentage of trypan blue positive cells in the total population of both stained and unstained cells as dead and viable, respectively (Banerjee et al., 2014).

2.11.2. Alamar blue method

Following the kit protocol (Alamar blue cell viability assay reagent, Thermo Scientific, USA), 20 μl of alamar blue was added to the cells in 200 μl of media in 96- well plates and incubated for 2 h with 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air at 37°C. Fluorescence (λex 545 nm, λem 590 nm) was determined in a Spectramax Gemini EM spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Percentage viability of the cells was determined by the ratio of the fluorescence in the treated to the untreated groups of cells.

2.12. Assessment of CL externalized to the mitochondrial surface

To assess CL externalized on the outer leaflet of the OMM, mitochondria were treated with phospholipase A2 (PLA2) from porcine pancreas (0.7 U/mg protein) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in mitochondria isolation buffer (210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 2 mM CaCl2 and 100 μM DTPA for 45 min at 4°C. To prevent mitochondrial damage by CL hydrolysis products, fatty acid-free human serum albumin (20 mg/ml) was added to the incubation medium. At the end of incubation, lipids were extracted using the Folch procedure (Folch et al., 1957). Mono-lyso-CL formed in PLA2 driven reaction was analyzed by LC/MS using a Dionex Ultimate™ 3000 HPLC coupled on-line to a Q- Exactive hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) as previously described (Tyurina et al., 2014). Mono-lyso-CLs were separated on a normal phase column (Silica Luna 3μm, 100A, 150x2 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) with flow rate 0.2 mL/min using gradient solvents containing 5mM CH3COONH4 (A - n-hexane:2- propanol:water, 43:57:1 (v/v/v) and B - n-hexane:2-propanol:water, 43:57:10 (v/v/v). Mono-lyso-CL (tri-myristoyl-lyso-CL) was prepared from tetra-myristoyl-CL (Avanti polar lipids, Alabaster, AL, USA) by PLA2 hydrolysis and used as internal standard.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

All the values are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance between two groups was tested by unpaired Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare among three or more experimental groups followed by post hoc test using Fisher’s LSD when appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Inhibition of KGDHC activity by the specific inhibitor CESP

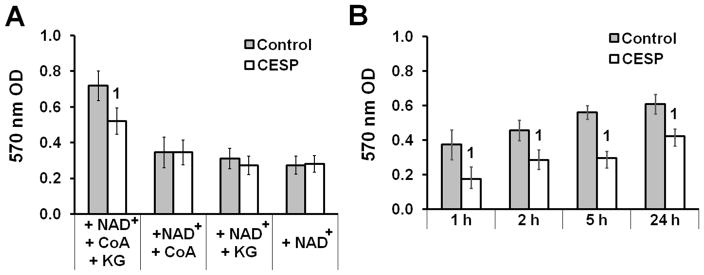

The succinyl phosphonates (SP) are very specific inhibitors of KGDHC (Bunik et al., 2005). The carboxy ethyl ester of SP (CESP) is the most cell-permeable form. Once in cells it is rapidly converted to SP and the latter selectively inhibits intracellular KGDHC. SP does not inhibit a variety of other dehydrogenases including pyruvate dehydrogenase, glutamate dehydrogenase, lactate dehydrogenase or malate dehydrogenase (Bunik et al., 2005). The cytochemistry assay allows assessment of KG-dependent KGDHC activity in the SH-SY5Y cellular environment. KGDHC activity requires the simultaneous presence of NAD+, CoA and KG (Fig. 1A); additionally, CESP causes significant inhibition of KGDHC activity compared to that of control only in the concomitant presence of the three reactants (Fig. 1A). CESP inhibited KGDHC activity by 53%, 33%, 47% and 23% at 1, 2, 5 and 24 h respectively (Fig. 1B). Diethyl ester of SP (DESP, a less active analogue of SP) did not decrease KGDHC activity (data not shown) when SH-SY5Y cells were treated with equimolar concentration at similar times.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of in situ KGDHC activity by CESP. SH-SY5Y cells were incubated in non-FBS media with (CESP) or without (control) 100 μM CESP for 1, 5 or 24 h as detailed in Materials and Methods section. KG (3 mM), CoA (1 mM) and NAD+ (3 mM) of the assay mix were combined to form the following four test groups: (1) NAD+ + CoA+ KG, (2) NAD+ + CoA, (3) NAD+ + KG (4) NAD+. (A) 570 nm OD readings among the different groups reveal that all the three reactants (KG, CoA, NAD+) are simultaneously required for maximal KGDHC activity. The necessity of these reactants was determined for each time point (data not shown). (B) Effects of CESP on the KG-dependent KGDHC activity at multiple time points. All experiments were independently run for four times in triplicate. Values are means ± SEM of the number of observations. Statistical comparisons were done by unpaired Student’s t-test. 1Denotes statistically significant difference compared to control (p < 0.05).

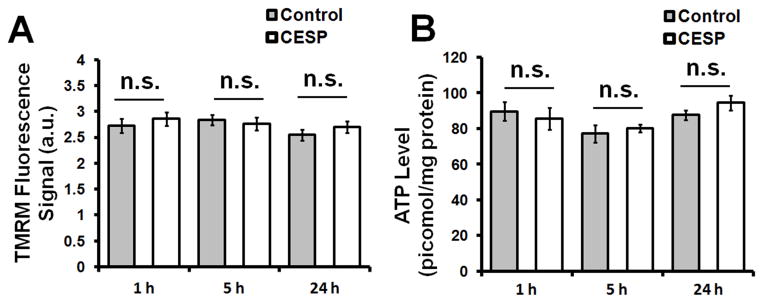

3.2. Inhibition of KGDHC did not alter the MMP nor ATP production

Changes in MMP and ATP levels are sensitive indicators of altered mitochondrial energy production within cells. Inhibition of KGDHC with 100 μM CESP for 1, 5 and 24 h did not have any significant effect on the MMP (Fig. 2A). Additionally no changes in ATP production was seen at these similar time-points (Fig. 2B). Thus KGDHC inhibition by CESP did not affect cellular energy in terms of MMP and ATP production, at least up to 24 h.

Figure 2.

Determination of MMP and ATP levels following KGDHC inhibition. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 μM CESP for 1, 5 or 24 h to inhibit KGDHC as detailed in the Materials and Methods section. (A) KGDHC inhibition did not alter MMP. After CESP treatment, cells were loaded with TMRM to estimate MMP. Inhibition of KGDHC with 100 μM CESP for 1, 5, or 24 h did not alter MMP. Values are means ± SEM of three separate experiments (total 1563 cells, 758 cells from 24 dishes in control group, and 683 cells from 24 dishes in CESP group). (B) KGDHC inhibition did not alter ATP levels. After treatment, ATP levels were measured using ATP determination kit. Values are the means ± SEM from three independent experiments (total 54 wells: 27 wells in control and 27 wells in CESP-treated group). Statistical comparisons were done by unpaired Student’s t-test. n.s. indicates non-significant difference between the indicated groups.

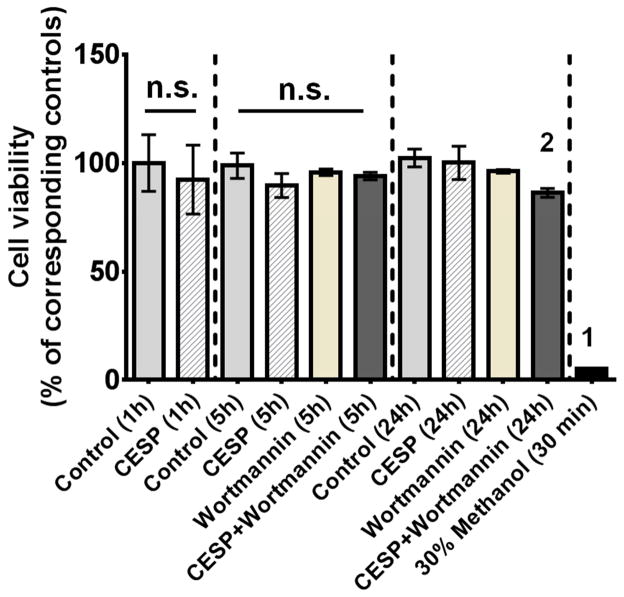

3.3. Inhibition of KGDHC and cell viability

Mild inhibition of KGDHC did not alter cell death, but it induced changes that made the cells more sensitive to inhibition of autophagy. CESP treatment (100 μM) did not alter viability at 1, 5 or 24 h (Fig. 3). The positive control (30% methanol treatment for 30 min) caused a near complete loss of viability. Wortmannin, an inhibitor of autophagy, did not cause cell death alone. However, the combination of Wortmannin and CESP did induce cell death at 24 h (Fig. 3B). The findings suggest that increased autophagy is protective in the setting of diminished KGDHC activity.

Figure 3.

Relation of cell death and autophagy following inhibition of KGDHC. Cell viability was measured in SH-SY5Y cells after treatment with 100 μM CESP for 1, 5 or 24 h to inhibit KGDHC as detailed in the Materials and Methods section. Methanol (30% for 30 minutes) was used as the positive control every time. No significant differences in cell death were observed with KGDHC inhibition at any time point. Simultaneous inhibition of KGDHC activity and autophagy for 24 h (i.e. CESP + Wortmannin 24 h group) resulted in significant cell death as compared to control [t(14) = 2.206. p < 0.05]. Values are expressed as means ± SEM of three independent experiments. Comparisons between a particular treatment group and the corresponding control at indicated time-points (1, 5 and 24 h) were done by unpaired Student’s t-test. 2Denotes significant difference between the (CESP + Wortmannin) and the control groups at 24 h time-point [t(6) = 4.544, p < 0.01]. Comparison among all the groups showed a significant difference [F10,84 = 7.051, p < 0.001] which was due to the differences between the positive control and all other groups (denoted by 1 on the positive control bar). n.s. indicates non- significant difference between the indicated groups.

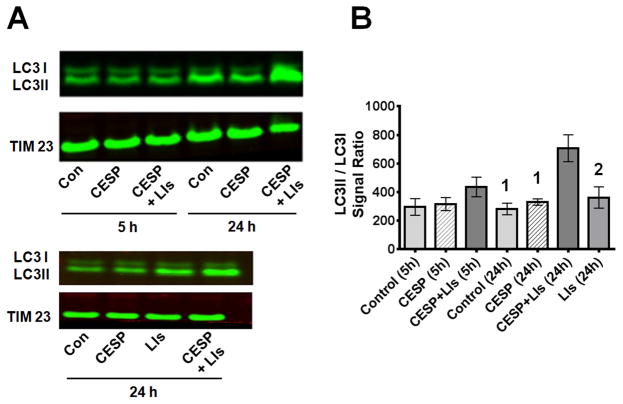

3.4. Inhibition of KGDHC induces autophagy/mitophagy

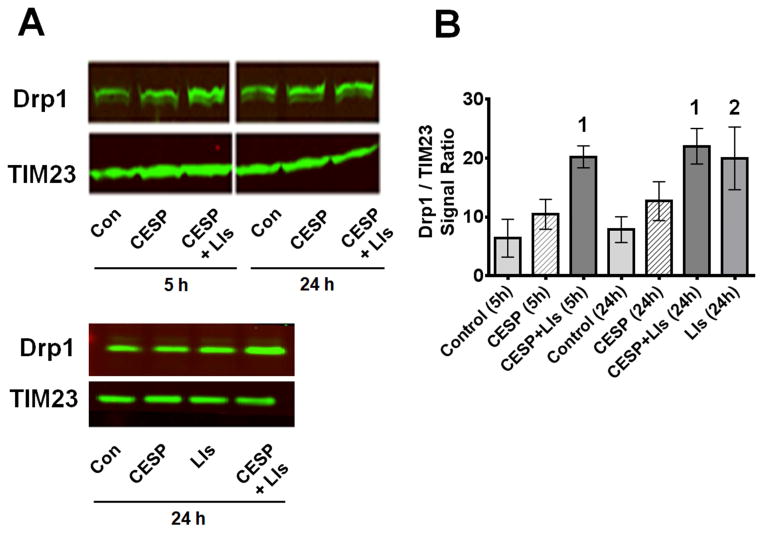

The next experiments tested whether inhibition of KGDHC induced autophagy / mitophagy by examining the distribution of the autophagic proteins. The mitochondrial LC3II/LCI ratio (Fig. 4) or Drp1 translocation (Fig. 5) to the mitochondria are early indicators of autophagy and mitochondrial fission. Formation of LC3II from LC3I occurs during the initiation of autophagy/mitophagy and their ratio is a marker for autophagosome formation. CESP did not alter the LC3II/LC3I ratio at 5 h and only slightly but non-significantly at 24 h (Fig. 4). CCCP, the positive control, increased the LC3II/LC3I ratio by four fold (data not shown). Drp1, which is cytosolic, moves to the mitochondria when the mitochondria become dysfunctional. Movement of Drp1 to the mitochondria disrupts mitochondrial biogenesis and increases mitochondrial fission. CESP treatment resulted in a slight yet non-significant increase of mitochondrial Drp1 at 5 h and 24 h (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

LC3II/LC3I protein in mitochondria following inhibition of KGDHC. (A) SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 μM CESP for 5 or 24 h and the LC3II/LC3I ratio were determined by Western blot. E64D and pepstatin A were used as LIs to inhibit degradation of mitochondria. Mitochondria were isolated and mitochondrial protein was loaded for the Western blot. TIM23 was used as the mitochondrial marker. (B) Densitometric analysis of the Western blot bands s(LC3II/LC3I) are shown graphically. Values are expressed as means ± SEM of three independent experiments. Comparisons were done by ANOVA [F6,20 = 6.150, p < 0.001] and post hoc comparisons were performed using Fisher’s LSD. The values for the groups with different numbers differ significantly from (CESP + LIs) at 24h (1denotes p < 0.001; 2denotes p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of KGDHC with CESP induced Drp1 translocation to mitochondria in the presence of LIs. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 μM CESP for 5 or 24 h and were processed to determine the Drp1/TIM23 ratio by Western blot. TIM23 was used as mitochondrial marker. Lysosomal degradation was inhibited with LIs containing pepstatin A and E64D as detailed in the Materials and Methods section. (B) Densitometric analysis of the Western blot bands (Drp1/TIM23) are plotted graphically. Values are expressed as means ± SEM of three independent experiments. Comparisons among groups were done by ANOVA [F6,14 = 3.944, p = 0.016] and post hoc comparisons were performed with Fisher’s LSD. Values with different numbers (1, 2) indicate statistical significant differences compared to the control at similar time-points (1denotes p < 0.01 vs. control 5 h; 2 denotes p < 0.05 vs. control 24 h).

Although changes in LC3II/LC3I and Drp1 suggest that CESP did not induce autophagy/mitophagy, another possibility is that compromised mitochondria that were marked by LC3II/LC3I or Drp1 were digested by lysosomes to maintain the health of the mitochondria. To test this possibility cells were treated with LIs with or without CESP for 5 or 24 hours. These inhibitors increased the LC3II/LC3I ratio (Fig. 4) and Drp1 (Fig. 5) on their own, and the increases were much greater in the presence of CESP. Thus, lysosomal digestion of mitochondria was important in preventing cell death and masked the induction of mitophagy.

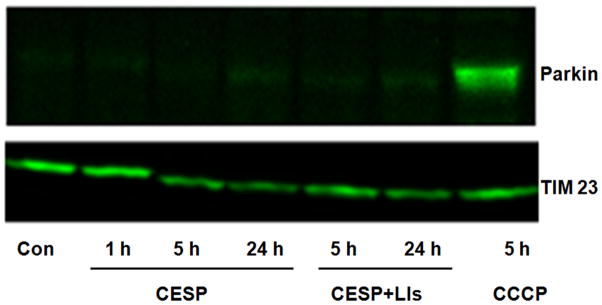

Since mitophagy can be induced by both parkin-dependent and parkin-independent methods and parkin translocation is the common first step in all parkin-dependent mitophagy, we tested the effects of reduced KGDHC on parkin movement. Although parkin movement to the mitochondria was clear in the positive control (i.e., CCCP-treated), inhibition of KGDHC did not cause parkin migration to the mitochondria even if the LIs were present to block degradation of parkin (Fig. 6). Thus, under our experimental conditions, although inhibition of KGDHC induced mitophagy, parkin was not involved in the process.

Figure 6.

Parkin translocation in KGDHC inhibited cells. Treatment with 100 μM CESP for 1, 5 or 24 h did not cause translocation of parkin to mitochondria. Forty μg protein from the mitochondrial fractions were loaded for Western blot. LIs (Pepstatin A andE64D) were used to inhibit lysosomal degradation. Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP, 5 μM) was used as a positive control which showed parkin translocation to mitochondria. TIM23 was used as the mitochondrial marker. The figure shows one of the identical results obtained from three independent experiments.

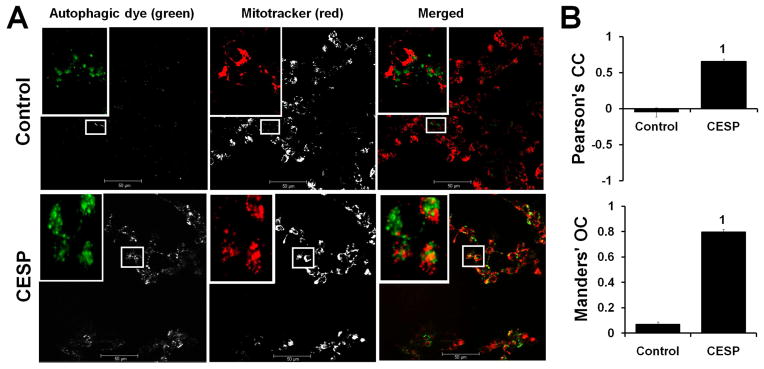

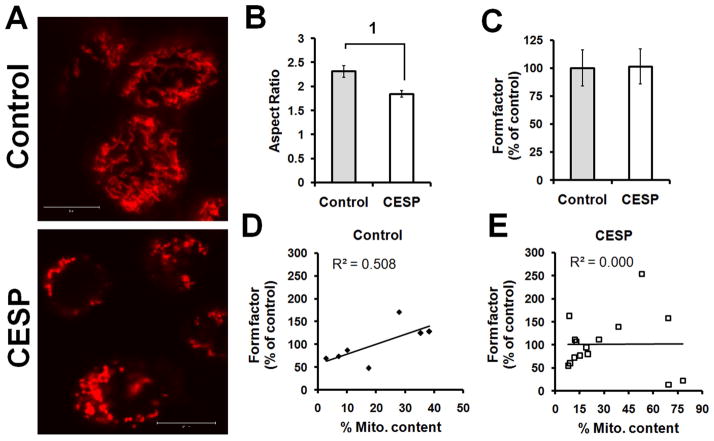

Morphological features are relatively more sensitive measures of autophagy and our data clearly indicate that diminished KGDHC activity induced mitophagy. The effects of CESP on autophagy/mitophagy were tested by confocal microscopy (Fig. 7). Autophagic green dye was used to bind with the autophagosomes (autophagic vacuoles) to detect autophagy. Mitotracker red binds only with mitochondria. Thus, specific mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) is detected by yellow color (merged mitotracker red and autophagy detecting green) (Fig. 7). The 24 h treatment with CESP increased autophagy (green) and mitophagy (yellow) (Fig. 7A). The quantification by PCC and MOC indicated that co-localization of the mitochondria with the autophagosomes in the CESP-treated group was significantly stronger and higher (ps < 0.001) compared to that in the control (Fig. 7B). The shapes of mitochondria provide another measure of the ongoing mitochondrial repair processes. CESP changed the morphology from normal elongated shape to smaller fragmented mitochondria as evidenced by the significant reduction of the aspect ratio (p < 0.001) (Fig. 8A and B), but it did not affect the form factor of the organelle (Fig. 8C). Correlational analysis (Fig. 8D and E) of the mitochondrial content with the form factor showed a positive near-significant correlation in the control group (R2 = 0.508, p = 0.072) and absence of any correlation in the CESP-treated group (R2 = 0.000, p = 0.971). Thus, both Western blot analysis of LC3 and Drp1, and the mitochondrial morphological changes demonstrate that a mild reduction in KGDHC induces mitophagy.

Figure 7.

Co-localization of autophagic vacuoles and mitochondria following inhibition of KGDHC. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 μM CESP for 24 h. Cells were stained with mitotracker red (mitochondria-specific dye) and autophagic green (autophagy vacuole-binding dye) and examined by confocal microscopy. (A) Representative double-staining confocal images showing the patterns of co-localization of mitochondria (red) and autophagosomes (green) in control (upper panel) and CESP-treated (lower panel) groups. Autophagic dye (green) column showing grayscale images obtained with green channel and mitotracker (red) column showing grayscale images obtained with red channel are merged by ImageJ software showing the RGB image in the merged column. Control shows no significant co-localization while CESP-treated group shows significant co-localization as evident by the yellow fluorescence. Selected areas show the amplified images. Split channel images have been shown in grayscale for better appreciation of image details. Scale bars represent 50 μm. The experiment was repeated three times which showed similar results. (B). Quantitative analysis of the co-localization using ImageJ software shows that both the Pearson’s CC and the Mander’s OC of the CESP-treated group (PCC = 0.65664, MOC = 0.79809) was significantly higher than the control group (PCC = −0.05080, MOC = 0.07020). 1Denotes statistical significant difference between the control and the CESP groups (p < 0.001). Five ROI were analyzed from three independent experiments. CC: Correlation coefficient, OC: Overlap coefficient.

Figure 8.

CESP induces mitophagy as indicated by change in mitochondrial morphology. Mitochondria were stained with mitotracker red dye as detailed in Materials and Methods section. (A) Representative confocal image of the control (upper panel) and after 24 h of CESP treatment (lower panel) of SH-SY5Y cells. The control cells show long, tubular mitochondria, while the CESP -treated cells show smaller, fragmented mitochondria. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial aspect ratio shows significant decline in the CESP-treated group compared to that in the control. 1Denotes p < 0.001 between the groups. (C) Form factor shows no differences between the groups. (D, E) Correlational analysis between the mitochondrial content and the form factor shows near-significant positive correlation in the control group (R2 = 0.508, p = 0.072) while no correlation in the CESP-treated group (R2 = 0.000, p = 0.971). In such quantifications a minimum of six ROI were analyzed from three independent experiments.

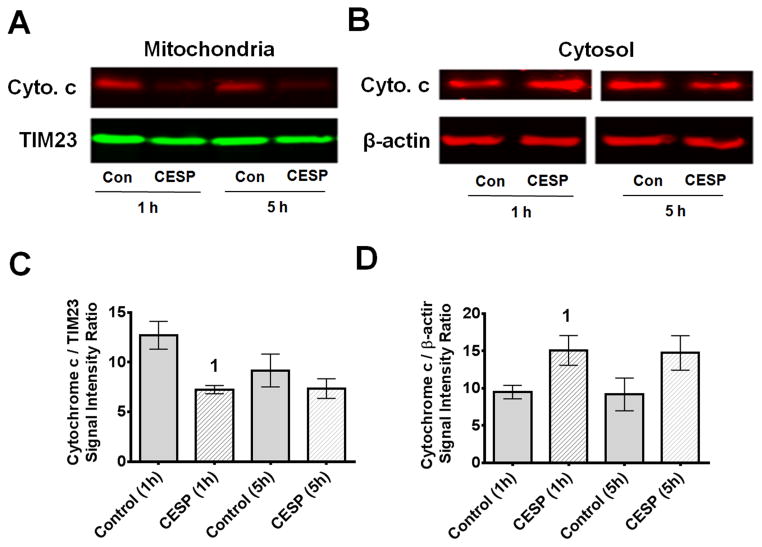

3.5. Inhibition of KGDHC promotes cytochrome c release from mitochondria

Cytochrome c is normally present inside the mitochondria. One hour treatment with CESP decreased cytochrome c in the mitochondria and increased cytochrome c concentration in the cytosol (Fig. 9). Thus, mild inhibition of KGDHC altered protein signaling within the cells.

Figure 9.

Inhibition of KGDHC decreased mitochondrial cytochrome c and increased cytosolic cytochrome c. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 μM CESP for 1 or 5 h and processed for Western blot experiments. TIM23 was used as mitochondrial marker and β-actin was used as cytosolic marker. Thirty μg of mitochondrial and 80 μg of cytosolic proteins were loaded for the Western blot experiments. (A, B) Representative bands from mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions. (C, D) Average densitometric data of mitochondrial and cytosolic blots are shown graphically. Values are means ± SEM of four experiments. Comparisons were done with unpaired Student’s t-test. Mitochondrial cytochrome c is significantly reduced [t(6) = 3.761, p = 0.009] while cytosolic cytochrome c is significantly increased [t(6) = 2.553, p < 0.043] compared to the respective controls at 1 h time-point. 1Denotes p < 0.05 compared to control at the same time-point (1 h).

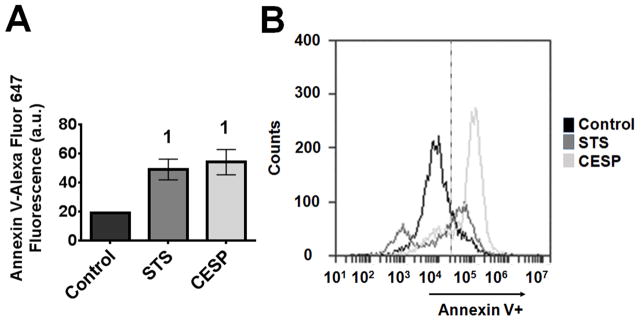

3.6. Inhibition of KGDHC induced changes in surface charge on the OMM

The charge of multiple anionic phospholipids present on the OMM can change in response to alterations in mitochondrial function. These signals are important to the regulation of protein signaling between mitochondria and the cytosol. Changes in surface charge can be estimated by detecting the binding of Annexin V (Fig. 10). CESP treatment for one h significantly increased (2.8 times) Annexin V fluorescence. The response to CESP was similar to the positive control, STS (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Inhibition of KGDHC increased Annexin V binding to mitochondria. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 μM CESP for 1 h. Annexin V was added according to the manufacturer’s instruction to the isolated mitochondrial sample in presence of 200 μM Ca++. Annexin V fluorescence was determined by flow cytometer. Mitotracker green was added to the cells and mitochondria were isolated. Finally the mitotracker green positive fractions were selected to see the Annexin V fluorescence by flow cytometer. Gating strategy for Annexin-V signal was fixed with all negative controls as 80% fall in the left (Annexin V negative) and 20% fall on the right side (Annexin V positive) of that gate. Then the percentage shift of Annexin V fluorescence of right side of all samples were measured and plotted in the graph. STS (1 μM) was used as a positive control. (A) Graphical representation of Annexin V fluorescence in the experimental groups (Control, STS and CESP). Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. Comparisons are done with unpaired Student’s t-test. 1Denotes statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to control. (B) Representative traces of Annexin V fluorescence from the three groups by flow cytometry.

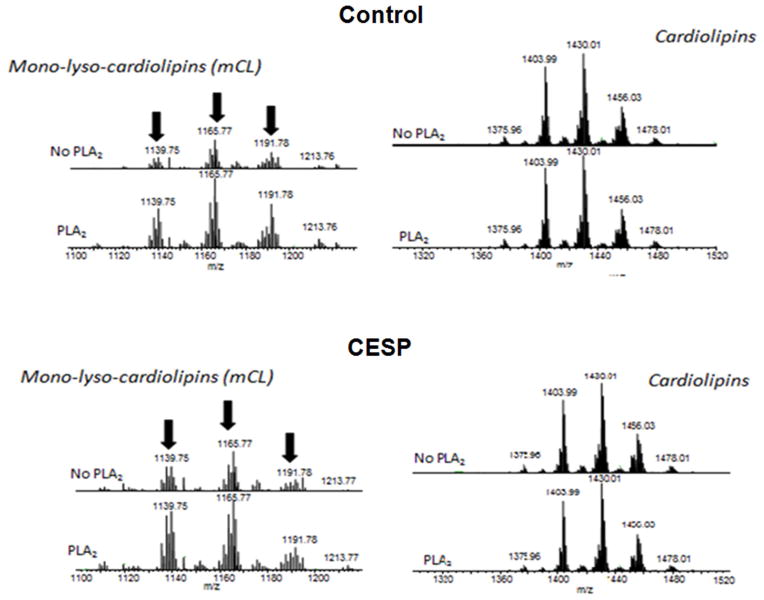

3.7. The signal for cytochrome c release is not externalization of CL

Mitochondrial surface charge as measured with Annexin V often reflects changes in CL content (Chu et al., 2013). CL is present in the IMM and holds cytochrome c within the mitochondria. The movement of CL from the IMM to the OMM can initiate the release of cytochrome c as well as mitophagy. Externalized CL can be measured by the formation of mono- lyso-cardiolipin (mCL) following the treatment of isolated mitochondria with PLA2, which hydrolyzes externalized CL to produce mCL. Mitochondrial samples incubated without any PLA2 treatment were used to normalize the minimum CL externalized during the process of isolation. CESP did not alter CL distribution in the mitochondrial membranes. The amount of mCL formed by the action of PLA2 in the group treated with CESP was not different from the amount of mCL formed in the PLA2-treated control group (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Mitochondrial cardiolipin externalization is not involved in the induction of mitophagy and release of cytochrome c. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 μM CESP for 1 h. Mitochondria were isolated and incubated with or without PLA2. The formation of mCL from the hydrolysis of externalized CL by PLA2 was measured by mass spectrometry. The spectra show that inhibition of KGDHC did not increase the formation of mCL following the treatment with PLA2.

4. Discussion

Mild impairment of oxidative metabolism accompanies many neurodegenerative diseases and is especially well documented in AD (Furst et al., 2012; Herholz, 2010). A key component in this reduction seen in AD is a decline in the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme complex KGDHC (Gibson et al., 1988; Gibson et al., 2005). Targeting this abnormality as a tool to developing new therapeutic drug molecules can provide an extremely viable option in the treatment of this devastating disorder. The first strategy by which this potential goal might be achieved is by preventing the reduction of KGDHC activity after understanding the underlying mechanisms, while the second one is to understand and prevent the downstream consequences of such reduction. In this study, we have tried to unfold the downstream consequences of the reduction of KGDHC activity in human neuroblastoma cell line.

Previous in vivo experiments from our laboratory showed that reducing KGDHC activity from 14.0 ± 0.43 mU / mg protein in wild type to 10.11 ± 0.34 mU / mg protein in E3-deficient mice (p < 0.001) by creating approximately one-half of wild type activity for E3 (a critical subunit in KGDHC) is associated with some oxidative stress making the cells extremely sensitive to other insults (Klivenyi et al., 2004). Thus, our in vitro experiments with reduced KGDHC activity are a reasonable model to pursue this mechanism. The model used in the present study reduced in situ KGDHC activity (23–53%) (Fig. 1) which is almost similar to that observed in the activity measures of KGDHC from post-mortem brains of AD patients (~50%) (Bubber et al., 2005, Gibson et al., 2005). This inhibition, however, did not produce any changes in the MMP and ATP production at any time-point studied (Fig. 2); additionally, it did not lead to cell death (Fig. 3). Although this mild inhibition of KGDHC by CESP itself did not alter cell death, it made the cells more vulnerable to autophagic inhibition by Wortmannin (Fig. 3). Wortmannin, an inhibitor of autophagy, did not cause cell death alone. However, the combination of Wortmannin and CESP did induce cell death (Fig. 3). This suggests that increased autophagy with diminished KGDHC is cytoprotective. Thus, mild impairment of KGDHC is associated with induction of certain cytoprotective mechanism in the long run while causing no overt changes in the energy levels within the cells at the level of MMP and ATP changes.

Injured or dysfunctional mitochondria generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and release mediators that kill cells. In order to protect the cells from these harmful agents, the dysfunctional mitochondria must either be repaired or removed from the cells; otherwise the cells will die. The repair occurs through mitochondrial fission and fusion and ultimately by the removal of the damaged mitochondria via autophagy/mitophagy. Our current results showing increased translocation of LC3 and Drp1 to mitochondria (Fig. 4 and 5) suggest that diminishing KGDHC activity induces mitophagy. Our data suggest that compromised mitochondria (that were marked by LC3 and Drp1) were digested by lysosomes to maintain the health of the mitochondria. LIs increased the LC3II/LCI ratio and Drp1 on their own, and the increases were much greater in the presence of KGDHC inhibition by CESP (Fig. 4 and 5). Thus, lysosomal digestion of mitochondria is important in preventing cell death. Our confocal microscopy data confirm the induction of autophagy/mitophagy (Fig. 7) and fragmentation / fission (Fig. 8) following KGDHC inhibition. Since earlier studies have shown that Drp-1 translocation to the mitochondria marks the initiation of mitophagy, we have checked this phenomenon only as an additional measure to confirm that mitophagy is initiated in our experimental system (Frank et al., 2012; Kubli and Gustafson, 2012; Zuo et al., 2014). Taken together, our findings, therefore, suggest the existence of autophagy/mitophagy induced by KGDHC inhibition in our experimental system. This may be responsible for the cytoprotection that we observed. The results in our study are consistent with the suggestion that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) expression within the cells increases to maintain the mitochondrial number by enhancing biogenesis (data not shown). Considerable evidence supports the notion that following mitochondrial stress and decreased ATP synthesis, high AMP can cause increase in PGC-1α generation (Chan, 2006). However, we did not find any significant alteration of ATP level after KGDHC inhibition suggesting the existence of some yet unknown plausible underlying signaling mechanisms that preserve the intracellular energy during the process. It is possible that KGDHC inhibition causes activation of the intracellular energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) as a response to oxidative-stress (Arsikin et al., 2012), although we have not explored the latter aspect in the present study. Since activation of AMPK causes compensatory increase in cellular ATP supply by suppressing ATP-consuming anabolic pathways and by activating alternative ATP-producing metabolic pathways by differentially regulating extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and other signaling pathways (Kim et al., 2001), we speculate these involvements in our system as well that preserve the ATP levels. Previous studies from our lab showed the induction of oxidative stress following KGDHC inhibition. Several kinases and phosphatases present in mitochondria can control cellular signaling and functions of mitochondrial proteins by phosphorylating/dephosphorylating them. This can also modify the mitochondrial membrane structure. An increase in mitochondrial numbers (mitogenesis) is also regulated by protein signaling from the mitochondria to the nucleus. The activation of expression of PGC-1α results in a robust increase in mitochondrial number and cellular respiration in many cell types (Liang and Ward, 2006). If the reparative and regenerative processes of fission/fusion or mitophagy are not successful, the mitochondrial protein signaling pathways can stimulate apoptotic cell death. Drp1 is the primarily involved protein for mitochondrial fission or fragmentation; and our study shows translocation of Drp1 (Fig. 5) to the mitochondria after KGDHC inhibition. The morphological alterations of mitochondria after the treatment of KGDHC shows more fragmented mitochondria in CESP-treated cells compared to the control cells (Fig. 8), which can be taken as another hallmark of Drp1 activity in our experimental system.

Since mitochondrial damage can initiate parkin translocation to the mitochondria and induce mitophagy (Vives-Bauza et al., 2010), we explored the role of this protein in context of our present findings. We observed that inhibition of KGDHC in our experimental system did not cause mitochondrial migration of parkin even if the LIs were present to block mitochondrial degradation by lysosomes (Fig. 6; Narendra et al., 2008). Thus, mitophagy must have been induced by other mechanisms. Since CL migration to the OMM promotes migration of pro-apoptotic signals to the mitochondria thereby releasing cytochrome c, we found it intriguing to explore the role of CL and cytochrome c in our experimental settings. In our previous study (Gibson et al., 2012) as well as in the present one (Fig. 9), we found cytochrome c release from mitochondria following KGDHC inhibition at one hour but not at later time points. This might be a possible signaling molecule that initiates autophagy to protect the cells from ongoing damage, although we have not explored this aspect in our present study. Previous results from our lab have also shown that similar inhibition of KGDHC causes cytochrome c translocation from the mitochondria to the cytosol along with caspase-3 activation without detectable changes in MMP and reactive oxygen species (Huang et al., 2003). In our present study, we have therefore focused only on exploring the specific aspects of autophagy/mitophagy occurring as a result of KGDHC inhibition. If the mitophagic machinery fails to eliminate the damaged mitochondria, externalized CL may then undergo oxidation as a prelude to apoptosis (Chu et al., 2013). Studies from others show that CL externalization can act as a signal for inducing mitophagy (Chu et al., 2013), while our data indicate that impairing KGDHC activity did not increase CL on the OMM (Fig. 11) but it altered the anionic PL levels of OMM (Fig. 10). Thus CL migration to OMM is not involved in induction of autophagy/mitophagy in our experimental system.

The mechanisms for inducing mitophagy with a reduction in KGDHC are not clear. Changes in MMP are sensitive indicators of altered mitochondrial function and modulate intracellular protein trafficking. The MMP was not altered by reduced KGDHC activity (Fig. 2A). The increased Annexin V binding to mitochondria with reduced KGDHC (Fig. 10) suggests that altered KGDHC can change the surface charge on the mitochondria, and this suggests multiple probabilities for mitophagy initiation. Annexin V is one member of the family of calcium and phospholipid binding proteins. Early ellipsometry studies that focused on phosphatidylserine demonstrate that adsorption proteins is calcium-dependent and is completely reversible upon calcium depletion (Andree et al., 1990; Chu et al., 2013; Hara et al., 2006; Harris-White et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2009; Vives-Bauza et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2009). Treatments that alter membrane phospholipids and/or their charge will alter Annexin V binding (Andree et al., 1990). Cells undergoing apoptosis loose plasma membrane asymmetry, such that high levels of phosphatidylserine become exposed on the cell surface. These cells can be recognized by staining with Annexin V, which binds to phosphatidylserine with high affinity. Increased Annexin V binding to the OMM has been related to the induction of mitophagy (Chu et al., 2013). The molecules responsible for Annexin V binding to mitochondrial membranes are not extensively studied. Diminished KGDHC may increase the levels of various metabolites before KGDHC. For example, loss of fumarase activity causes accumulation of intracellular fumarate, which can directly modify cysteine residues to form 2-succinocysteine through succination (Ternette et al., 2013) and this could alter the surface charge on the mitochondria. KGDHC can also modify lysine groups by succinylation (Gibson et al., 2015; Jang et al., 2012) which changes the charge and shape of molecules.

As confirmed from our earlier studies (Huang et al., 2003; Shi et al., 2009), sensitive parameters of mitochondrial energy metabolism like the MMP are less sensitive to the impaired activity of KGDHC than the cytochrome c release and subsequent cellular changes. We have observed similar findings of our present study as well. Another previous study has also shown that some carbon derived from KG bypass the block in TCA cycle at the level of KGDHC inhibition by means of GABA shunt (Santos et al., 2006). Thus, our previous study employing data from various approaches including GC/MS, 13C NMR, HPLC/MS has confirmed that a mild reduction in KGDHC - a situation very much similar to that of our present study - alters metabolism by enhancing glycolysis and GABA shunt (Shi et al., 2009). Although here we didn’t check other respiration experiments, our data from the previous and the present studies strongly support the notion that some compensatory mechanisms are playing their roles in maintaining MMP and intracellular ATP levels.

Another possible mechanism for induction of mitophagy with impaired KGDHC is by altered [NAD+]/[NADH] ratio (Jang et al., 2012). Since KGDHC catalyzes the conversion of α-KG to succinyl CoA in presence of the coenzyme A thereby reducing NAD+ to NADH, the decrease in KGDHC activity would be expected to increase the [NAD+]/[NADH] ratio. Exposure of cells to nicotinamide decreases mitochondrial content and increases the MMP by activating autophagy and inducing mitochondrial fragmentation. The effect of nicotinamide is mediated through an increase of the [NAD+]/[NADH] ratio and the activation of SIRT1, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase that plays a role in autophagy flux. The [NAD+]/[NADH] ratio is inversely correlated with the mitochondrial content, and an increase in the ratio resulted in autophagy activation and mitochondrial transformation from lengthy filaments to short dots (Jang et al., 2012). Treatment of cells with SIRT1 activators induced similar changes in the mitochondrial content (Jang et al., 2012). Together, our results might indicate that a metabolic state resulting in an elevated [NAD+]/[NADH] ratio can modulate mitochondrial quantity and quality via pathways that may include SIRT1-mediated mitochondrial autophagy (Jang et al., 2012). Inhibition of KGDHC can lower the production and supply of NADH to mitochondrial electron transport chain which can probably alter MMP and ATP production. Although the reduction in KGDHC can accumulate KG which can trigger isocitrate to produce more succinate by the action of isocitrate lyase, this will produce more succinate to feed complex II and maintain the cellular ATP production as well as maintain normal transmembrane potential (Mills and O’Neill, 2014).

Release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol is a well characterized mitochondrial response to cellular stress. A pool of CL-bound mitochondrial cytochrome c functions as a peroxidase, catalyzing CL peroxidation that promotes release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors from mitochondria (Kagan et al., 2005). Although this is a key event in the induction of apoptotic cell death, post-mitotic cells, such as neurons, can restrict apoptosis even after cytochrome c release from the mitochondria, enabling recovery from mitochondrial damage and survival. For example, in mouse neurons, apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) prevents the proteasome-dependent degradation of cytochrome c in response to induced mitochondrial stress. P53-associated parkin-like cytoplasmic protein (PARC, also known as CUL9) is an E3 ligase that targets cytochrome c for degradation in neurons (Gama et al., 2014). Neurons are remarkably capable of maintaining MMP despite the loss of cytochrome c, in part by maintaining ATP generation through glycolysis. Cytochrome c release requires Bax binding, and Bax can only bind to a specific length of mitochondria (Clerc et al., 2014). Fragmented mitochondria are not ideal for Bax binding, thus fragmentation of mitochondria can reduce the release of cytochrome c. Altered mitochondrial/ cytosolic cytochrome c or release of cytochrome c from mitochondria can also be caused by altered MMP, opening of MPT pores, high Ca2+, mitochondrial swelling and CL peroxidation.

5. Future directions

Since mitochondrial degeneration is one of the earliest pathological signs of AD and morphological abnormalities of the organelle within the neurons of different subcortical areas like the thalamus, globus pallidus, red nucleus and locus coeruleus indicate generalized mitochondrial dysfunction in AD patients (Baloyannis, 2006), it is important to understand the mechanisms of such mitochondrial alterations in the setting of the disease. Earlier mitochondrial morphometric studies from the brains of AD patients have shown that the organelle undergoes reduction in length and diameter suggestive of mitochondrial fission in humans (Baloyannis, 2006). Similar findings in our present in vitro cell-based model of reduced energy metabolism (a pathognomonic feature of AD) suggest a proof of concept to visualize the mitochondrial derangements that might underlie the pathogenesis of AD. However, since the SH-SY5Y cells used in our present study are dissimilar to the differentiated neurons, it will be prudent to examine the effects of KGDHC inhibition on the mitochondrial autophagy, dynamism and morphometry in differentiated primary neurons in the future, or in neurons derived from humans through pluripotent stem cells

6. Conclusions

Mitochondrial dysfunction occurs with several diseases. Thus this organelle has been suggested as a therapeutic target in several diseases including neurodegenerative diseases, heart failure, diabetes and cancer (Sorriento et al., 2014). Our previous studies show that a short-term reduction in KGDHC caused a different response than long term or chronic reductions in both calcium levels and the response to external oxidants (Gibson et al., 2012). For example, a short-term reduction in KGDHC similar to that in the current studies enhances the ability to diminish oxidants, whereas a long-term reduction diminishes the ability to buffer external oxidants (Gibson et al., 2012). These studies of reduced KGDHC inducing mitophagy support the suggestion that diminished KGDHC can be protective in the short-term. Hence, increased fission and mitophagy induced by mild impairment of mitochondrial function is protective in the short-term, but ultimately makes the cells more sensitive to other conditions that impair metabolism. Thus, a therapy that initially promotes autophagy followed by activation of mitochondria by compounds such as benfotiamine or PGC-1α to increase healthy mitochondria may be beneficial to control mitochondrial damage and neuronal loss in neurodegenerative diseases like AD.

Figure 12.

Schematic representation of the changes induced by KGDHC inhibition in relation to mitochondria. KGDHC inhibition (shown by arrow pointing down) by CESP increases (shown by arrows pointing up) negatively charged PLs (independent of CL externalization), translocation (shown in gray arrows) of cytosolic Drp1 (black triangles) and LC3 (gray rectangles) to mitochondria, cytosolic [cytochrome c] (gray circles), mitochondrial fission, mitochondrial mass, and mitophagy without altering (represented by horizontal two-way pointing arrows) MMP and intracellular ATP level.

Highlights.

Effects of KGDHC inhibition in SH-SY5Y cells were tested.

ATP and mitochondrial membrane potential were unchanged.

Drp1 and LC3 translocated to mitochondria.

Mitochondrial negative surface charges, fission and autophagy were increased.

Regulation of KGDHC activity and mitophagy are potential therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by grants NS065789 (CTC), AG026389 (CTC), NIH-PP- AG14930 (GEG) and by the Burke Medical Research Institute.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AIF

Apoptosis inducing factor

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- BSS

Balanced salt solution

- CCCP

Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenyl hydrazone

- CESP

Carboxy ethyl ester of succinyl phosphonate

- CL

Cardiolipin

- DESP

Diethyl ester of succinyl phosphonate

- Drp1

Dynamin-related protein-1

- DTPA

Diethylenetriamine penta acetate

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- EMEM

Eagle’s minimum essential medium

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- KG

α-ketoglutarate

- KGDHC

α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex

- LC3

Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

- LIs

Lysosomal inhibitors

- mCL

Mono-lyso-cardiolipin

- MMP

Mitochondrial membrane potential

- MOC

Mander’s overlap coefficient

- MPT pore

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- OMM

Outer mitochondrial membrane

- PCC

Pearson’s correlation coefficient

- PGC-1α

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator

- PLA2

Phospholipase A2

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

- STS

Staurosporine

- TCA cycle

Tricarboxylic acid cycle

- TIM

Translocase of the inner membrane

- TMRM

Tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester

- VDAC

Voltage-dependent anion channel

Footnotes

Conflicts

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Authors’ Contributions:

KB and GEG conceived and designed the whole study. KB performed most of the experiments. KB and GEG analyzed and interpreted the data. HX did the KGDHC activity assay and HC did the MMP and ATP assays. KB, SM and GEG wrote the article and contributed with critical intellectual content. SM helped in the analysis and interpretation of the data on cell viability, co-localization and morphometric assays. DEF assisted in all western blot works and helped in analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. CTC and VEK also contributed critically to draft this manuscript. CTC, VEK and YYT did the mass spectrometry experiments and analyzed the data. JY and SC did the FACS experiments. CTC, VEK, JY, SC and JFJ designed the FACS experiments and analyzed the data with KB. TTD prepared CESP and contributed critically to writing this paper. All authors reviewed and approved of the final version of the manuscript. All authors fulfilled the criteria for authorship.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler J, Parmryd I. Quantifying co-localization by correlation: The pearson correlation coefficient is superior to the mander’s overlap coefficient. Cytometry A. 2010;77:733–742. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andree HA, Reutelingsperger CP, Hauptmann R, Hemker HC, Hermens WT, Willems GM. Binding of vascular anticoagulant alpha (VAC alpha) to planar phospholipid bilayers. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4923–4928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsikin K, Kravic-Stevovic T, Jovanovic M, Ristic B, Tovilovic G, Zogovic N, Bumbasirevic V, Trajkovic V, Harhaji-Trajkovic L. Autophagy-dependent and -independent involvement of AMP-activated protein kinase in 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity to SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:1826–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloyannis SJ. Mitochondrial alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2006;9:119–126. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee K, Munshi S, Frank DE, Gibson GE. Abnormal Glucose Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease: Relation to Autophagy/Mitophagy and Therapeutic Approaches. Neurochemical Research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee K, Munshi S, Sen O, Pramanik V, Roy Mukherjee T, Chakrabarti S. Dopamine Cytotoxicity Involves Both Oxidative and Nonoxidative Pathways in SH-SY5Y Cells: Potential Role of Alpha-Synuclein Overexpression and Proteasomal Inhibition in the Etiopathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson’s Disease. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/878935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubber P, Haroutunian V, Fisch G, Blass JP, Gibson GE. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer brain: Mechanistic implications. Annals of Neurology. 2005;57:695–703. doi: 10.1002/ana.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunik VI, Denton TT, Xu H, Thompson CM, Cooper AJL, Gibson GE. Phosphonate Analogues of α-Ketoglutarate Inhibit the Activity of the α-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complex Isolated from Brain and in Cultured Cells. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10552–10561. doi: 10.1021/bi0503100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, de Brito OM, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, Scorrano L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808249105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in mammals. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2006;22:79–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT, Ji J, Dagda RK, Jiang JF, Tyurina YY, Kapralov AA, Tyurin VA, Yanamala N, Shrivastava IH, Mohammadyani D, Qiang Wang KZ, Zhu J, Klein-Seetharaman J, Balasubramanian K, Amoscato AA, Borisenko G, Huang Z, Gusdon AM, Cheikhi A, Steer EK, Wang R, Baty C, Watkins S, Bahar I, Bay?r H, Kagan VE. Cardiolipin externalization to the outer mitochondrial membrane acts as an elimination signal for mitophagy in neuronal cells. Nature Cell Biology. 15:1197–1205. doi: 10.1038/ncb2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc P, Ge SX, Hwang H, Waddell J, Roelofs BA, Karbowski M, Sesaki H, Polster BM. Drp1 is dispensable for apoptotic cytochrome c release in primed MCF10A and fibroblast cells but affects Bcl-2 antagonist-induced respiratory changes. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;171:1988–1999. doi: 10.1111/bph.12515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estaquier J, Arnoult D. Inhibiting Drp1- mediated mitochondrial fission selectively prevents the release of cytochrome c during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1086–1094. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank M, Duvezin-Caubet S, Koob S, Occhipinti A, Jagasia R, Petcherski A, Ruonala MO, Priault M, Salin B, Reichert AS. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2012;1823:2297–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst AJ, Rabinovici GD, Rostomian AH, Steed T, Alkalay A, Racine C, Miller BL, Jagust WJ. Cognition, glucose metabolism and amyloid burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2012;33:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama V, Swahari V, Schafer J, Kole AJ, Evans A, Huang Y, Cliffe A, Golitz B, Sciaky N, Pei X-H, Xiong Y, Deshmukh M. The E3 ligase PARC mediates the degradation of cytosolic cytochrome c to promote survival in neurons and cancer cells. Science Signaling. 2014 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghibelli L, Coppola S, Fanelli C, Rotilio G, Civitareale P, Scovassi AI, Ciriolo MR. Glutathione depletion causes cytochrome c release even in the absence of cell commitment to apoptosis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1999;13:2031–2036. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson GE, Chen HL, Xu H, Qiu L, Xu Z, Denton TT, Shi Q. Deficits in the mitochondrial enzyme alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase lead to Alzheimer’s disease-like calcium dysregulation. Neurobiology of Aging. 2012;33:1121, e13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson GE, Xu H, Chen HL, Chen W, Denton TT, Zhang S. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex-dependent succinylation of proteins in neurons and neuronal cell lines. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2015;134:86–96. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G, Blass J, Beal MF, Bunik V. The alpha-ketoglutarate-dehydrogenase complex. Molecular Neurobiology. 2005;31:43–63. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G, Sheu K, Blass J, Baker A, Carlson K, Harding B, Perrino P. Reduced activities of thiamine-dependent enzymes in the brains and peripheral tissues of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:836–840. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520320022009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. Multiple pathways of cytochrome c release from mitochondria in apoptosis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 2006;1757:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes LC, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial morphology in mitophagy and macroautophagy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2013;1833:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Mishima K, Saito I, Okano H, Mizushima N. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-White ME, Ferbas KG, Johnson MF, Eslami P, Poteshkina A, Venkova K, Christov A, Hensley K. A cell-penetrating ester of the neural metabolite lanthionine ketimine stimulates autophagy through the mTORC1 pathway: Evidence for a mechanism of action with pharmacological implications for neurodegenerative pathologies. Neurobiology of Disease. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herholz K. Cerebral glucose metabolism in preclinical and prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2010;10:1667–1673. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HM, Ou HC, Xu H, Chen HL, Fowler C, Gibson GE. Inhibition of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex promotes cytochrome c release from mitochondria, caspase-3 activation, and necrotic cell death. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:309–317. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SY, Kang HT, Hwang ES. Nicotinamide-induced mitophagy: event mediated by high NAD+/NADH ratio and SIRT1 protein activation. J BiolChem. 2012;287:19304–19314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.363747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan VE, Tyurin VA, Jiang J, Tyurina YY, Ritov VB, Amoscato AA, Osipov AN, Belikova NA, Kapralov AA, Kini V, Vlasova II, Zhao Q, Zou M, Di P, Svistunenko DA, Kurnikov IV, Borisenko GG. Cytochrome c acts as a cardiolipinoxygenase required for release of proapoptotic factors. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:223–232. doi: 10.1038/nchembio727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama Y, Hoshijima M, Seo K, Bedja D, Sysa-Shah P, Andrabi SA, Chen W, Höke A, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Gabrielson K, Kass DA, Iijima M, Sesaki H. Parkin-independent mitophagy requires Drp1 and maintains the integrity of mammalian heart and brain. The EMBO Journal. 2014;33:2798–2813. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuppagounder SS, Pinto JT, Xu H, Chen LH, Beal MF, Gibson GE. Dietary supplementation with resveratrol reduces plaque pathology in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochem Int. 2009;54:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Yoon MY, Choi SL, Kang I, Kim SS, Kim YS, Choi YK, Ha J. Effects of stimulation of AMP-activated protein kinase on insulin-like growth factor 1- and epidermal growth factor-dependent extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19102–19110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klivenyi P, Starkov AA, Calingasan NY, Gardian G, Browne SE, Yang L, Bubber P, Gibson GE, Patel MS, Beal MF. Mice deficient in dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase show increased vulnerability to MPTP, malonate and 3-nitropropionic acid neurotoxicity. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;88:1352–1360. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubli DA, Gustafsson AB. Mitochondria and mitophagy: The yin and yang of cell death control. Circ Res. 2012;111:1208–1221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemasters JJ. Selective Mitochondrial Autophagy, or Mitophagy, as a Targeted Defense Against Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Aging. Rejuvenation Research. 2005;8:3–5. doi: 10.1089/rej.2005.8.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Lau A, Morris TJ, Guo L, Fordyce CB, Stanley EF. A syntaxin 1, galpha(o), and N-type calcium channel complex at a presynaptic nerve terminal: Analysis by quantitative immunocolocalization. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4070–4081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0346-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Ward WF. PGC-1α: a key regulator of energy metabolism. Advances in Physiology Education. 2006;30:145–151. doi: 10.1152/advan.00052.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Cheng H, Zhou Y, Zhu Y, Bian R, Chen Y, Li C, Ma Q, Zheng Q, Zhang Y, Jin H, Wang X, Chen Q, Zhu D. Myostatin induces mitochondrial metabolic alteration and typical apoptosis in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e494. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losón OC, Song Z, Chen H, Chan DC. Fis1, Mff, MiD49, and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in mitochondrial fission. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2013;24:659–667. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Stokes K, Mahngar K, Domazet-Damjanov D, Sikorska M, Pandey S. Inhibition of stress induced premature senescence in presenilin-1 mutated cells with water soluble Coenzyme Q10. Mitochondrion. 2014;17:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melser S, Chatelain Etienne H, Lavie J, Mahfouf W, Jose C, Obre E, Goorden S, Priault M, Elgersma Y, Rezvani Hamid R, Rossignol R, Bénard G. RhebRegulates Mitophagy Induced by Mitochondrial Energetic Status. Cell Metabolism. 2013;17:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill RA, Dagda RK, Dickey AS, Cribbs JT, Green SH, Usachev YM, Strack S. Mechanism of neuroprotective mitochondrial remodeling by PKA/AKAP1. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills E, O’Neill LA. Succinate: A metabolic signal in inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Gong N, Zhao J, Yu Z, Gu F, Chen J, Sun X, Zhao L, Yu M, Xu Z, Dong W, Qin Y, Fei G, Zhong C, Xu TL. Powerful beneficial effects of benfotiamine on cognitive impairment and beta-amyloid deposition in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 transgenic mice. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2010;133:1342–1351. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park LC, Calingasan NY, Sheu KF, Gibson GE. Quantitative alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activity staining in brain sections and in cultured cells. Analytical biochemistry. 2000;277:86–93. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SS, Gibson GE, Cooper AJL, Denton TT, Thompson CM, Bunik VI, Alves PM, Sonnewald U. Inhibitors of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex alter [1–13C]glucose and [U-13C]glutamate metabolism in cerebellar granule neurons. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2006;83:450–458. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Chen HL, Xu H, Gibson GE. Reduction in the E2k subunit of the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex has effects independent of complex activity. J BiolChem. 2005;280:10888–10896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Risa O, Sonnewald U, Gibson GE. Mild reduction in the activity of the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex elevates GABA shunt and glycolysis. J Neurochem. 2009;109(Suppl 1):214–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorriento D, Pascale AV, Finelli R, Carillo AL, Annunziata R, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G. Targeting Mitochondria as Therapeutic Strategy for Metabolic Disorders. The Scientific World Journal. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/604685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Tan KO, Fu NY, Sukumaran SK, Chan SL, Kang JH, Poon KL, Chen BS, Yu VC. MAP-1 is a mitochondrial effector of bax. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:14623–14628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503524102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]