Abstract

This study proposes a time-varying effect model that can be used to characterize gender-specific trajectories of health behaviors and conduct hypothesis testing for gender differences. The motivating examples demonstrate that the proposed model is applicable to not only multi-wave longitudinal studies but also short-term studies that involve intensive data collection. The simulation study shows that the accuracy of estimation of trajectory functions improves as the sample size and the number of time points increase. In terms of the performance of the hypothesis testing, the type I error rates are close to their corresponding significance levels under all combinations of sample size and number of time points. Furthermore, the power increases as the alternative hypothesis deviates more from the null hypothesis, and the rate of this increasing trend is higher when the sample size and the number of time points are larger.

Keywords: Longitudinal data, time-varying effect, mixed effect, B-spline, substance abuse

1 Introduction

Historically, in many fields of health science such as alcohol and substance abuse research, participants were largely male. Thus, our knowledge of the relevant diseases has been built upon data from predominantly male samples. However, females and males are different not only biologically but also psychosocially. The complex interplay between these two types of factors at different developmental stages may result in gender differences that vary across time.1,2 For example, females’ earlier timing of physical puberty may put them at higher risk for alcohol use in early adolescence.3 Other biological factors may, however, prevent females from drinking alcohol in later developmental stages such as higher reactivity to alcohol and greater vulnerability to adverse health effects due to alcohol use.4 In addition, psychosocial factors such as greater social sanctions against females’ alcohol use may contribute to gender differences.4 In fact, the finding of a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population5 tends to reflect the diminishing gender-based drinking norms in the modern society. By understanding gender differences in developmental trajectories of alcohol use or drinking patterns, we may be able to tailor prevention and intervention efforts to the special timing and risky patterns of each gender group and, thus, thwart progression to worse outcomes.

According to our review of the empirical studies published in the past two decades, gender has been conventionally treated as a time-invariant effect, that is, both the magnitude and direction of gender differences remain unchanged over time.6,7 Yet, a recent study8 analyzed four waves of data from a nationally representative sample of adolescents and found similar developmental trajectories for alcohol use, nicotine use, and marijuana use by gender: females tended to be involved in higher levels of substance use in early adolescence, whereas males exhibited greater increases across time and higher levels of use in mid-adolescence and early adulthood. An important limitation of the methodology used in the study is that the developmental trajectories for all the three substances were derived by fitting quadratic growth models that pre-specified a simple shape for developmental changes, which may contribute to the similarity in trajectories across substances. In addition, gender differences were tested implicitly through the interactions between the group indicator and linear/quadratic terms. Such simple shapes can hardly characterize the complex developmental trajectories of substance use, especially when there are many time points spanning a long developmental period.

In recent years, the time-varying effect model (TVEM) has been introduced and extended for broader applications in the substance abuse field.9–14 The TVEM explicitly characterizes gender differences in developmental trajectories of substance use across the critical period by modeling gender as a time-varying effect, which can be easily understandable to the scientific community as well as the general public through graphical presentation. Such trajectories are estimated through non-parametric regression functions that do not assume fixed shapes like conventional growth curves, and thus may reveal different timing of prevention and intervention for gender groups. Furthermore, this kind of model can be applied to not only multi-wave longitudinal studies, but also short-term studies that involve intensive data collection methods such as ecological momentary assessment or daily diaries, which are becoming more popular for studying patterns of health behaviors.15–18 Although these two types of studies are different in terms of the duration between time points, the numbers of time points and the richness of data in both studies tend to be beyond what traditional parametric methods can fully characterize.

This study proposes a TVEM to (1) characterize gender-specific trajectories of health behaviors and (2) conduct hypothesis testing for gender differences. We demonstrate an application of the model using longitudinal data from a well-known prospective study on the development of substance use and abuse, the Michigan Longitudinal Study (MLS),19 that is following high-risk youth from childhood to adulthood. Another application of the model is demonstrated by using daily diary data from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS).20 The MIDUS data were also used to design a simulation study evaluating the performance of the proposed method in terms of the accuracy of estimation of trajectories, type I error rate, and statistical power under different conditions.

2 The model

Let Y(tij) be the j-th observed outcome from the i-th subject at tij (i = 1, …, …, N; j = 1, …, …, Ji) and k be the group (e.g. gender) that Subject i belongs to (k = 1, 2). We consider the following nonparametric generalized mixed effect model for the measurement

| (1) |

where g(·) is a known link function under the framework of generalized linear models21; μ(tij) is the trajectory of the k = 2 group; β(tij) delineates the time-varying difference between the two groups; and bi is a random individual effect modeling within-subject correlation, and is assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance σ2. The distribution of Y(tij) is thus completely characterized by μ(tij), β(tij) and bi. One advantage of this model over fitting a separate non-parametric trajectory for each group is that β(tij) can characterize the group difference across time explicitly.

The time-varying coefficients in model (1) can be represented using basis expansions. Thus, the nonparametric functions μ(tij), β(tij) are treated as linear combinations of several known parametric functions. We choose to use a spline basis to represent them as piecewise cubic functions. On each of several intervals defined by knots, the spline function is cubic. At a knot, the spline function is continuous and has continuous first and second derivatives, although the third derivative may be discontinuous at the knots. This allows any smooth shape to be approximated well if enough knots are used. Specifically, we use a B-spline basis,22 which can be automatically generated by most commonly used statistical software packages such as SAS and R, for a given set of knots. The basis functions are always non-negative, and each is zero over most of the interval, so that each knot’s basis function is orthogonal to the other basis functions except for its closest knot neighbors. However, overfitting may still occur with a B-spline basis if too many knots are used. For simplicity, in this paper, we adopt the approach of Shiyko et al.23 that used a small number of equally spaced knots and treated the selection of the number of basis functions as a model selection problem.

After defining the basis functions using the B-spline formula, equation (1) can be written as a parametric form

| (2) |

where ϕ1(tij), …, ϕP(tij) and ψ1(tij), …, ψQ(tij) are known functions of time defined using the recursive B-spline formulas; ξ1, …, ξP and ζ1, …, ζQ are the corresponding regression coefficients. Equation (2) is thus a generalized linear mixed model with P + Q + 1 parameters. For the binary case, the likelihood function for Subject i is

where pij = P(Y(tij) = 1|bi). For the continuous case, it is

where f (y(tij)) stands for the density function of Y(tij). The likelihood function for the entire sample is thus . We use the R-package lme4 to derive the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters.

In practice, researchers are interested in graphing gender-specific trajectories. Based on the fixed effects in Equation (2), the trajectory for the k = 2 group is . For the k = 1 group, the trajectory is . The delta method can be used to estimate the variance of the estimated functions of these two groups at any time t. In this way, we can obtain the pointwise confidence intervals which can be plotted along with the estimated trajectories.

Researchers are also interested in testing whether there exists any gender difference. We formulate this hypothesis testing problem as follows

Under H0, the two groups have the same trajectory (i.e. there is no group difference). Following the method described above, we can estimate μ(t) under H0, as well as μ(t) and β(t) under H1. We can further evaluate the log-likelihood functions under H0 and H1 denoted by ℓ(H0) and ℓ(H1), respectively. The generalized likelihood ratio test (GLRT) for the hypothesis can thus be defined by T = 2{ℓ(H1) − ℓ(H0)}. Following Cai et al.,9 we can conduct bootstrap sampling to estimate the p-value for the GLRT.

3 The motivating examples

We use two well-known studies in the field of health behavior research to demonstrate that the proposed model can be applied to not only multi-wave longitudinal studies, but also short-term studies that involve intensive data collection such as daily process studies.

3.1 The Michigan longitudinal study (MLS)

The MLS is an ongoing prospective study of people at high risk for substance abuse and disorder.19 It is the developmentally earliest study currently extant and is also one of the longest running projects in the field of substance abuse. We chose to use data from the MLS to demonstrate the application of the proposed method, because the study is highly influential, and the features of the data are typical in the field. Thus, our methodological work may have high applicability to the field. More importantly, these rich longitudinal data provide a rare opportunity for us to examine gender differences in alcohol use developmentally. Such investigation could shed some light on future prevention and intervention work.

The MLS recruited participant families using fathers’ drunk driving conviction records and door-to-door community canvassing in a four-county area in mid-Michigan. All participants received extensive in-home assessments of their substance use and related risk factors and consequences at baseline, and thereafter at three-year intervals. The children of participant families were followed from early childhood to adulthood. During the critical developmental period of alcohol use onset and peak use (early adolescence to young adulthood), these children were assessed annually in order to measure drinking onset and patterns more accurately. In this study, we use longitudinal data (ages 12 to 26) from a sample of 699 children (70.2% males) for analysis. The maximum number of time points available is 15, although some participants may skip certain time points.

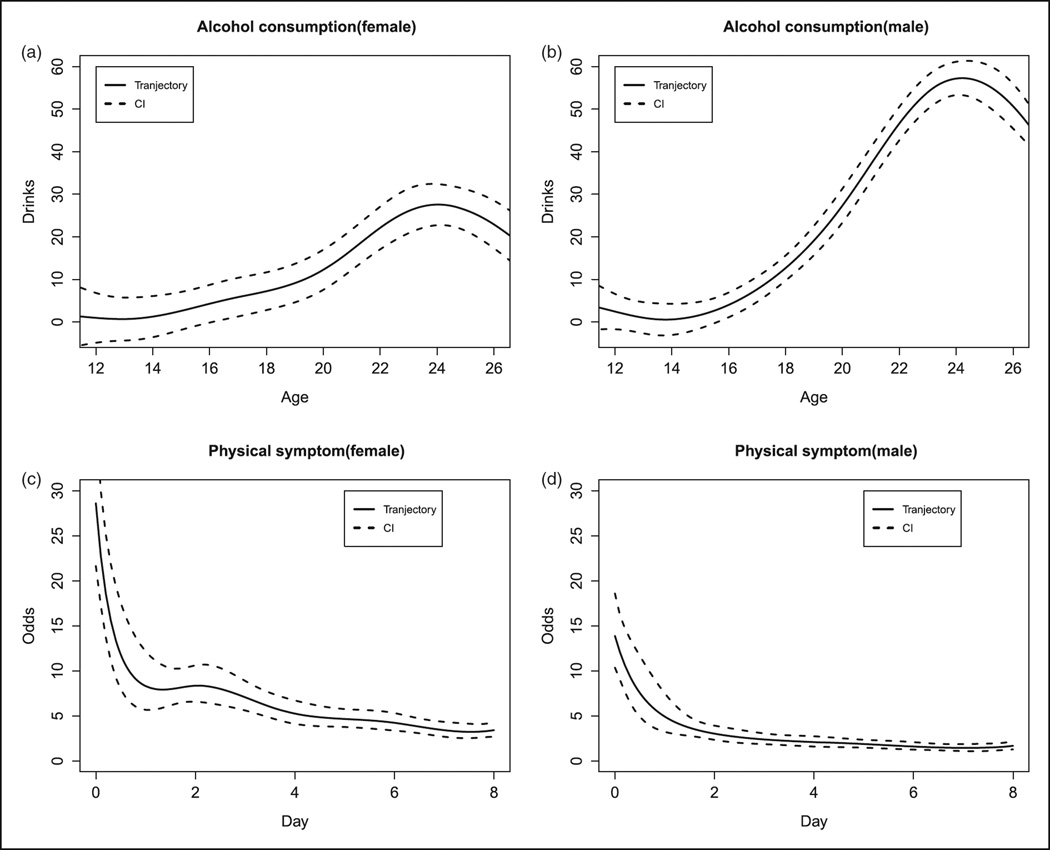

Our investigation aims to (1) characterize gender-specific alcohol use behavior developmentally from early adolescence to young adulthood, and (2) test gender differences in developmental trajectories. In our analysis, the outcome at each time point is a composite measure of alcohol consumption, which is the product of the number of drinking days in past month and the average number of drinks per drinking day. Gender is treated as a time-varying effect through β(t) in model (1); the link function g(·) is the identity. Using AIC and BIC, we choose five knots to approximate the trajectories. Panels (a) and (b) in Figure 1 show the developmental trajectories of females and males, respectively. Using the asymptotic normality of the resulting estimate, the asymptotic pointwise confidence intervals (CI) of the trajectories of group 1 and group 2 (i.e. μ(t) + β(t) and μ(t)) at time tij are

and

respectively, where Σξ and Σξ,ζ are the covariance matrices of the estimates of the covariates; Φ and Ψ are the B-spline basis used to fit the functions μ(t) and β(t), respectively. The two gender groups do not differ until middle adolescence. Although alcohol consumption for both groups increases from middle adolescence to young adulthood, the rate of change is much higher among males. Furthermore, the decreasing trend for both groups after age 24 probably reflects that people tend to “mature out” of heavy drinking due to family or job responsibilities. Moreover, the result of the GLRT indicates that there are significant gender differences with T = 161.29 and the corresponding p-value estimated to be around 0 by bootstrap sampling.

Figure 1.

Gender-specific trajectories based on the motivating examples.

3.2 The National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS II)

The Daily Stress Project of MIDUS II was designed to examine how sociodemographic factors, health status, personality characteristics, and genetic endowment modify patterns of change in exposure to day-to-day life stressors as well as physical and emotional reactivity to these stressors.20 The survey data were collected from 2022 non-institutionalized adults aged 35 to 85 in the United States from 2004 to 2009. Participants completed daily phone surveys on stressors, physical symptoms, and positive/negative affect for eight consecutive days.

Although daily process methods provide prospective data for examining the dynamic associations between health behaviors, they unavoidably involve self-monitoring of the target behavior, which is an active component of some cognitive-behavioral interventions.24 The potential measurement reactivity (defined as changing the target behavior due to self-awareness) is undesirable for those studies that aim to investigate the association between the target behavior and its precursor or consequence. On the other hand, for those applications aiming to facilitate behavior changes, such an effect can be used to boost or extend intervention effects.25 Thus, verifying measurement reactivity is an important research question, especially given that existing empirical investigations are few and have produced mixed results.26,27

Our investigation aims to (1) characterize the gender-specific patterns of change in self-reported physical symptoms during the eight days of assessment, and (2) test gender differences in patterns of change. In our analysis, the outcome at each time point is a binary variable for any physical symptoms reported in a day (1 = yes; 0 = no). Gender is treated as a time-varying effect through β(t) in model (1); the link function g(·) is the logit. Using AIC and BIC, we choose three knots to approximate the patterns of change. Panels (c) and (d) in Figure 1 show the patterns of change in the odds of reporting any physical symptoms for females and males, respectively. Females tend to have much greater odds of reporting physical symptoms, particularly in the first few days. Further, measurement reactivity is evident in both gender groups in the beginning of the assessment period. Moreover, the result of the GLRT indicates that there are significant gender differences with T = 50.42 and the corresponding p-value estimated to be about 0 by bootstrap sampling.

4 Simulation study

In this section, we examine the performance of the proposed method under different situations. The design of the simulation is based on the feature of the MIDUS data demonstrated in section 3. The response is a binary variable which follows model (1) with the link function g(·) being the logit function and the group indicator k = 1 corresponding to females. We generate the response Y using the estimated functions of μ(t), β(t), and bi from the fitted model of these national data. We manipulate four factors: (i) the sample size: N = 100, 200, and 400; (ii) the number of time points: J = 8 and 16; (iii) the proportion of zeros in the response Y from all participants across all waves: 30%, 50%, and 70%; and (iv) the gender ratio: 1 : 1 and 3 : 1. We expect that the performance improves with the sample size and the number of time points. We also expect that the proposed method may perform better in the setting with 50% zeros than in the other settings, because the former tends to have greater Fisher information. Furthermore, we expect the performance to be better when the sample sizes of the two gender groups are about the same.

4.1 The accuracy of estimation of trajectory functions

We evaluate the performance of the proposed method concerning the accuracy of the estimation of trajectory functions, μ(t) and β(t), under different combinations of the sample size, the number of time points and the proportion of zeros. It is straightforward to manipulate the former two factors. However, the proportion of zeros in the response is manipulated indirectly by altering μ(t) and β(t). Let μ̂0(t) and β̂0(t) be the trajectory functions in the model fitted on the national data. We obtain three different proportions of zeros, 30%, 50%, and 70%, through the following trajectory functions, respectively: (1) μ(t) = μ̂0(t) and β(t) = β̂0(t); (2) μ(t) = μ̂0(t) and β(t) = −2β̂0(t); and (3) μ(t) = −1.8 μ̂0(t) and β(t) = β̂0(t). Please note that the function μ(t) here refers to the one defined in equation (1) rather than the mean of the response Y. The criterion for evaluating the accuracy of estimation of trajectory functions is the mean integrated squared error (MISE)

Table 1 shows the MISE and its empirical standard error under different combinations of the three factors. Based on the table, the accuracy of the proposed method improves as the sample size and the number of time points increase. For example, when N = 100 and J = 8, the MISE and the corresponding standard error are larger in comparison to other settings with the same proportion of zeros in the responses. Controlling for the effects of sample size and number of time points, when the proportion of zeros increases from 30% to 50%, the performance of our method does not change much as demonstrated by the similar MISEs and standard errors. However, when the proportion of zeros increases from 50% to 70%, the performance of our method becomes worse based on the larger MISEs and standard errors. Furthermore, the performance of the method tends to be better when the gender ratio is 1 : 1 (like the national data example), in comparison to the setting when the gender ratio is 3 : 1 (like the MLS data example). However, the impact of gender ratio becomes unimportant when the proportion of zeros is 70% and the performance is poor anyway.

Table 1.

MISE under different sample sizes, numbers of time points, proportions of zeros, and gender ratios.

| N = 100 | N = 200 | N = 400 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion |

J = 8 Mean (SD) |

J = 16 Mean (SD) |

J = 8 Mean (SD) |

J = 16 Mean (SD) |

J = 8 Mean (SD) |

J = 16 Mean (SD) |

| Male:female = 1:1 | ||||||

| 30% | 0.387 (0.273) | 0.179 (0.112) | 0.171 (0.106) | 0.086 (0.048) | 0.082 (0.047) | 0.044 (0.023) |

| 50% | 0.287(0.183) | 0.148 (0.077) | 0.140 (0.080) | 0.078 (0.043) | 0.074 (0.038) | 0.042 (0.023) |

| 70% | 0.557 (0.444) | 0.306 (0.426) | 0.294 (0.323) | 0.140 (0.135) | 0.156 (0.176) | 0.071 (0.051) |

| Male:female = 3:1 | ||||||

| 30% | 0.417 (0.236) | 0.260 (0.401) | 0.231 (0.188) | 0.104 (0.067) | 0.099 (0.059) | 0.050 (0.028) |

| 50% | 0.319 (0.179) | 0.151 (0.081) | 0.153 (0.086) | 0.078 (0.039) | 0.077 (0.039) | 0.042 (0.022) |

| 70% | 0.453 (0.263) | 0.266 (0.241) | 0.288 (0.269) | 0.131 (0.102) | 0.126 (0.095) | 0.063 (0.041) |

4.2 The type I error rate and power of the hypothesis testing

We also evaluate the performance of the hypothesis testing in terms of the type I error rate and power. Our simulation involves the setting of H0 : β(t) = 0 versus H1 : β(t) = δβ̂(t), where β̂(t) is the trajectory function in the model fitted on the national data; and the value of δ is manipulated to reflect different levels of deviation from H0. In this part of the simulation study, we only manipulate the sample size and the number of time points because manipulating the proportion of zeros would require altering β(t). We also adopt the gender ratio in the national data when generating the gender of the subjects in the simulation samples. Because the proposed model is non-parametric, we can only derive the empirical distribution of the test statistics T = 2{ℓ(H1) − ℓ(H0)} through simulation. Under each combination of the sample size and the number of time points, we generate 10,000 data sets under H0 and then conduct the hypothesis testing which results in 10,000 values of T. The critical values of T0.01, T0.05, T0.10, T0.25 are thus the 99th, 95th, 90th, and 75th percentiles from this empirical distribution of T. After obtaining the critical values under each situation, we investigate the effect of δ on the power of the test by taking a grid of δ over (0, 2). Under each situation, we generate 1000 data sets for each value of δ and conduct the hypothesis testing on the data sets (using the four critical values) to examine the type I error rate and the power corresponding to the four values of α (i.e. significance levels). Table 2 shows the type I error rates (i.e. the values of power when δ=0), which are close to their corresponding significance levels under all settings. Figure 2 depicts the power as a function of δ and δ under different situations. As demonstrated by the figure, the power increases as δ increases and the value of power is 1 when δ is greater than 1.5. In addition, the rate of this increasing trend is higher when the sample size and the number of time points are larger.

Table 2.

Type I error rates under different sample sizes and numbers of time points.

| N = 100 | N = 200 | N = 400 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J = 8 | J = 16 | J = 8 | J = 16 | J = 8 | J = 16 | |

| α = 0.01 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.01 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.016 |

| α = 0.05 | 0.053 | 0.046 | 0.034 | 0.059 | 0.057 | 0.048 |

| α = 0.10 | 0.114 | 0.088 | 0.097 | 0.108 | 0.107 | 0.108 |

| α = 0.25 | 0.286 | 0.26 | 0.261 | 0.231 | 0.266 | 0.234 |

Figure 2.

Power curves under different sample sizes, numbers of time points, and significance levels.

5 Discussion

This study proposes a TVEM that can be used to characterize gender-specific trajectories of health behaviors and conduct hypothesis testing for gender differences. The major strengths of the model include (1) treating gender differences as a time-varying effect; and (2) modeling time-varying effects with flexible smooth functions derived from empirical data. The proposed model can be applied to not only multi-wave longitudinal studies like the MLS, but also short-term studies that involve intensive data collection such as the daily diary data from the MIDUS. Furthermore, the design of our simulation study is unique because it simulates the features of the MIDUS data so that the results can be generalizable to the field of health behavior research.

The simulation study shows that the accuracy of estimation of trajectory functions improves as the sample size and the number of time points increase. Controlling for the effects of these two factors, the proportion of zeros only has a considerable negative effect on accuracy when it increases from 50% to 70%. In terms of the performance of the hypothesis testing, the type I error rates are close to their corresponding significance levels under all combinations of sample size and number of time points. Furthermore, the power increases as the alternative hypothesis deviates more from the null hypothesis, and the rate of this increasing trend is higher when the sample size and the number of time points are larger.

Although the methodology proposed in this study was motivated by our research interest in gender differences, it can be applied to a variety of contexts that involve the comparison between two trajectories or change patterns. For example, the model can be used to characterize the developmental trajectory of substance use among children of alcoholic (COA) and compare it with the trajectory of non-COA. Future work may be needed to extend the methodology to handle the settings with more than two groups such as studying racial differences.

The proposed model accounts for subject-specific effects only through a random intercept. Thus, the outcomes of the same subject at any two time points are treated as equally correlated regardless of the size of the time difference between the time points, and this may not be realistic in some settings. Popular longitudinal models assuming autocorrelation for the residuals (such as AR-1), on the other hand, treat the lag between each consecutive pair of measurements as equivalent. This assumption may not apply to those settings that involve random or inconsistent measurement times. A more straightforward way to incorporate longitudinal correlation, therefore, is to add a random subject-level slope to the right-hand side of model (1). Further research is, thus, warranted regarding how best to implement more complex random effect structures while still allowing the time-varying effects to be easily estimated and interpreted with standard software.

In spite of the fact that the proposed model can handle a variety of measurement scales under the framework of generalized linear models such as continuous and binary outcomes (as demonstrated in our motivating examples), future work is needed to extend the model to deal with other scales that are also common in the health behavior field including ordinal outcomes10 and zero-inflated counts.28,29 Furthermore, our work in this paper focuses on the setting that involves a single health behavior. Future studies may consider modeling multiple health behaviors that tend to co-occur such as substance use behaviors, violence behaviors, and HIV sexual risk behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The work of Yang and Li was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [P50 DA010075, P50 DA036107 & R01 CA168676] and the National Science Foundation (NSF) [DMS 1512422]; The work of Cranford and Buu was supported by the NIH [R01 DA035183]; and Zucker’s research was supported by the NIH [R01 AA07065]; and The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH and NSF.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Buu A, Dabrowska A, Mygrants M, et al. Gender differences in the developmental risk for onset of alcohol, nicotine, and marijuana use and the effects of nicotine and marijuana use on alcohol outcomes. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:850–858. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buu A, Dabrowska A, Heinze JE, et al. Gender differences in the developmental trajectories of multiple substance use and the effect of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking in a high risk sample. Addict Behav. 2015;50:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wichstrom L. The impact of pubertal timing on adolescents’ alcohol use. J Res Adolescence. 2001;11:131–150. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Associations between exposure to stressful life events and alcohol use disorder in a longitudinal birth cohort studied to age 30. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith PH, Kasza KA, Hyland A, et al. Gender differences in medication use and cigarette smoking cessation: results from the international tobacco control four country survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:463–472. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Z, Fan J, Li R. Efficient estimation and inferences for varying-coefficient models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:888–902. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dziak JJ, Li R, Zimmerman MA, et al. Time-varying effect models for ordinal responses with applications in substance abuse research. Stat Med. 2014;33:5126–5137. doi: 10.1002/sim.6303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu AP, Li R. Quadratic inference functions for varying-coefficient models with longitudinal data. Biometrics. 2006;62:379–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan X, Shiyko M, Li R, et al. A time varying effect model for Intensive longitudinal data. Psychol Meth. 2012;17:61–77. doi: 10.1037/a0025814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Bo K, Li R. Local rank inference for varying coefficient models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2009;104:1631–1645. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2009.tm09055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu H, Li R, Kong L. Multivariate varying coefficient model for functional responses. Ann Stat. 2012;40:2634–2666. doi: 10.1214/12-AOS1045SUPP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Li R, Lanza ST, et al. Understanding the role of cessation fatigue in the smoking cessation process. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selya AS, Dierker LC, Rose JS, et al. Time-varying effects of smoking quantity and nicotine dependence on adolescent smoking regularity. Drug and Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasilenko S, Piper M, Lanza ST, et al. Time-varying processes involved in smoking lapse in a randomized trial of smoking cessation therapies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16S2:S135–S143. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang H, Cranford JA, Li R, et al. Two-stage model for time-varying effects of discrete longitudinal covariates with applications in analysis of daily process data. Stat Med. 2015;34:571–581. doi: 10.1002/sim.6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zucker RA, Ellis DA, Fitzgerald HE, et al. Other evidence for at least two alcoholisms ii: life course variation in antisociality and heterogeneity of alcoholic outcome. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8:831–848. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryff CD, Almeida DM. ICPSR26841-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Cosortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; [accessed 26 February 2010]. National survey of Midlife in the United States (MIDUS II): Daily Stress Project, 2004–2009. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR26841.v1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized linear models. London: Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Boor C. A practical guide to splines. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiyko MP, Lanza ST, Tan X, et al. Using the time-varying effect model (TVEM) to examine dynamic associations between negative affect and self-confidence on smoking urges: Differences between successful quitters and relapsers. Prevent Sci. 2012;13:288–299. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0264-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson TL, Kivlahan DR, Bush KR, et al. Telephone self-monitoring among alcohol use disorder patients in early recovery: a randomized study of feasibility and measurement reactivity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tucker JA, Blum ER, Xie L, et al. Interactive voice response self-monitoring to assess risk behaviors in rural substance users living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:432–440. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9889-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barta WD, Tennen H, Litt MD. Measurement reactivity in diary research. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 108–123. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stritzke WGK, Dandy J, Durkin K, et al. Use of interactive voice response (IVR) technology in health research with children. Behav Res Meth. 2005;37:119–126. doi: 10.3758/bf03206405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buu A, Johnson NJ, Li R, et al. New variable selection methods for zero-inflated count data with applications to the substance abuse field. Stat Med. 2011;30:2326–2340. doi: 10.1002/sim.4268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buu A, Li R, Tan X, et al. Statistical models for longitudinal zero-inflated count data with applications to the substance abuse field. Stat Med. 2012;31:4074–4086. doi: 10.1002/sim.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]