Abstract

Background

Physical inactivity significantly impacts mortality worldwide. Physical inactivity is a modifiable risk factor for obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic conditions. African American women in the U.S. have the highest rates of physical inactivity when compared to other gender/ethnic groups.1 A paucity of research promoting physical activity (PA) in African American women has been previously identified. The purpose of this review was to identify intervention strategies and outcomes in studies designed to promote PA in African American women.

Methods

Interventions that promoted PA in African American women published between 2000 and May 2015 were included. A comprehensive search of the literature was performed in Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, PsycINFO, CINAHL Complete, and MEDLINE Complete databases. Data were abstracted and synthesized to examine interventions, study designs, theoretical frameworks, and measures of PA.

Results

Mixed findings (both significant and nonsignificant) were identified. Interventions included faith-based, group-based, and individually focused programs. All studies (n = 32) included measures of PA; among the studies, self-report was the predominant method for obtaining information. Half of the 32 studies focused on PA, and the remaining studies focused on PA and nutrition. Most studies reported an increase in PA or adherence to PA. This review reveals promising strategies for promoting PA.

Conclusions

Future studies should include long-term follow-up, larger sample sizes, and objective measures of PA. Additional research promoting PA in African American women is warranted, particularly in studies that focus on increasing PA in older African American women.

Keywords: physical activity, intervention studies, African American, women

Physical inactivity is a leading risk factor for mortality worldwide.2 Physical inactivity is associated with heart disease and other chronic health conditions.1 According to the World Health Organization2, 1 in 3 adults worldwide are physically inactive. PA is defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure.”2 Healthy People 2020 estimated that more than 80 percent of adults in the U.S. do not meet the minimal recommended Center for Disease Control (CDC) PA guidelines,3 (i.e. recommendation of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity each week, plus strength-conditioning at least twice per week).4,5 For example, in an analysis of stroke and heart disease statistics reported in 2011, an estimated 24.5% of U.S. adults met the muscle-strengthening criteria; and 21.0% met both the muscle-strengthening and aerobic criteria.1 Increasing the proportion of adults who meet federal PA guidelines is one of the Healthy People 2020 established objectives. PA is essential to health promotion and decreases risk for various conditions, including but not limited to heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.4,5 In addition to reducing the risk of heart disease, meeting PA guidelines has been associated with lowering the risk of hypertension and hyperlipidemia.1,4

Heart disease is the leading cause of death for African American women6,7 African American women have a higher rate of risk factors associated with heart disease, including hypertension, physical inactivity, and obesity. African American women have the lowest rate of exercise and leisure time PA.8 Among African American women, 35.5% meet PA guidelines, compared to 50.9% for Non-Hispanic White women, 47.5% for African American men, and 56.4% for Non-Hispanic White men.1 According to data collected in 2011 by the US Department of Health and Human Services, African American women were 80% more likely to be obese than Non-Hispanic White women. 9 African American women had an obesity rate of 54.0%, compared to 38.3% for Non-Hispanic Black men and 32.5% for Non-Hispanic White women.9 The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Guideline on Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk5 suggests additional research is needed to determine strategies for effectively implementing evidence-based recommendations to improve cardiovascular health. Additional research is warranted to increase understanding of racial/ethnic/socioeconomic factors that may act as barriers and prevent adoption of PA recommendations.5 Healthcare providers, including cardiovascular nurses, can be actively involved in determining strategies to implement recommendations and promote adoption of PA recommendations. Promoting PA in African American women is an essential factor in reducing the risk of heart disease and other chronic health conditions. Therefore, it is important to understand which intervention strategies are most effective when promoting PA among African American women.

This integrative review examines intervention studies published between 2000 and May, 2015 that promote PA among African American women. It is important to note this review includes studies completed after the review by Banks-Wallace and Conn10 which examined 18 studies from1984 to 2000; seven specifically focused on African American women.10 Due to the paucity of research at the time, Banks-Wallace and Conn10 included studies that consisted of a sample of at least 35% African American women. The current review includes studies specifically focusing on African American women or studies reporting results separately for African American women. Race, ethnicity, and gender should be a central focus when developing and implementing effective PA interventions among specific populations; the inclusion of additional population subgroups other than African American women may unknowingly reduce the generalizability of results.8,11

METHODS

The purpose of this review is to identify intervention strategies and outcomes in studies designed to promote PA specific to African American women. As a result, interventions that solely focused on African American women or that reported findings separately for African American women were included. In addition, only intervention studies with direct measures of PA were included. Direct measures of PA included questionnaires, self-reporting, and objective measures such as pedometers and accelerometers. As recommended by Whittemore and Knafl12 five stages of review were completed: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation.

Problem Identification

Studies that met the following criteria were included in the search: 1) English language, 2) reported measures of PA in African American women, 3) published between January 2000 and May 2015, and 4) sample consisted of African American women only, or results were reported separately for African American women. Excluded were studies that did not report PA results by race and gender, as well as abstracts, and dissertations.

Literature Search

A literature search12 occurred in PsycINFO, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, CINAHL Complete and MEDLINE Complete electronic databases for studies published from January 2000 to May 2015. The following search terms were included: “physical activity” or “motor activity” or “exercise” and “African American or “Black” and “women” and “intervention”.

Data Evaluation

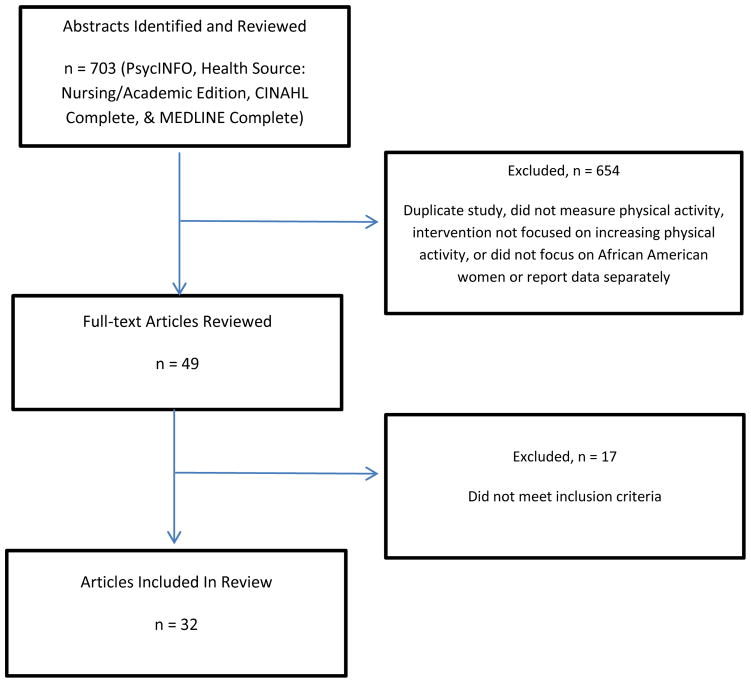

After abstracts were screened for duplicate studies and relevance, 32 articles were included in the review. Figure 1 provides a description of the search outcome. Studies included in this review were appraised using the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) criteria and the appraisal is shown in Table 1. The CEBM provides a framework for assessing the level of evidence.13 The majority of the selected studies were randomized controlled trials.14–27 After reviewing the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)28, the investigator determined that most of those randomized controlled trials adhered to the CONSORT reporting guidelines (60%). The most common omission was identification of the study as a randomized trial in the title.14,15,18,22,24,25,27

Figure 1.

Summary of search and screening results

Table 1.

Summary of Studies Reviewed

| Author | Purpose | Design/Level of Evidence |

Intervention | Theoretical Framework |

Sample/Location | Physical Activity Measure |

Physical Activity Outcomes |

Strengths/ Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams, Burns, Forehand, and Spurlock45 (2015) | Community-based walking intervention implemented to promote physical activity among African American women | Pre-Post 3 |

5 weekly group sessions to encourage support, walking groups | None identified | 25 out of 29 African American women completed intervention Setting: church (southeastern state) |

IPAQ (baseline and 1 week after intervention) | Time spent in moderate physical activity significantly increased Time spent sitting on a weekday decreased Time spent walking decreased |

Low attendance at some of the group sessions (reported causes of attrition were inclement weather and family obligations) |

| Anderson and Pullen16 (2013) | To determine whether cognitive-behavioral physical activity spiritual strategies (PASS) intervention would increase physical activity behavior in African American women ≥ 60 years old | Cluster, randomized study 2 |

PASS intervention – 90 minute sessions each week for 10 weeks

|

Health Promotion Model | 27 African American women Four faith communities in the southern United States Age: ≥ 60 years old; mean age 70 years (intervention) and 66 years (control) |

Total daily energy expenditure, self-reported moderate-intensity physical activity, walking minutes per week, muscle-strengthening activity days/week and minutes/week | Healthy People 2020 target for moderate-intensity physical activity reached by 73% (intervention) and 69% (control) Healthy People 2020 target for muscle strengthening activity reached by 73% (intervention) and 12.5% (control) Significant difference between groups for muscle strengthening activity (days and minutes/week) No significant difference for amount of moderate-intensity physical activity or total daily expenditure |

Strengths: Faith community setting, churches were randomized, theory-based intervention, and control group received intervention in their church after follow-up measures were taken Limitations: self-report physical activity and small sample |

| Backman et al.,30 (2011) | Evaluate effectiveness of Fruit, Vegetable, and Physical Activity Toolbox for Community Educators in changing knowledge, attitudes, and behavior among low-income African American women | Quasi-experimental prospective design 2 |

Intervention group received six, one-hour toolbox classes (one session/week) Control group did not receive intervention |

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) concepts | African American women - 156 (intervention group) and 171 (control group) Ages: 18 to 54 75% low-income 16% drop rate (intervention), 14% (control) Region: West |

Physical activity - Behavior change measured by self-report | Increased proportion of women who had been physically active for 5 or more days in previous week and in usual week (significant difference for intervention group) Significant difference for intervention group in using Physical Activity Scoreboard to create weekly physical activity routine |

Strength: random assignment to group Limitations: physical activity self-reported and possibility that participants in control group changed their behaviors due to their knowledge of nutrition and physical activity study |

| Banks-Wallace and Conn38 (2005) | Examine changes in steps per day over the course of a pilot study focusing on promoting walking | Pre-post, single arm 3 |

12 month group intervention included 3 hour monthly meeting (education and discussion about physical activity), group walks (started at 5 minutes and increased to 40 minutes) and at-home walking component Participants were asked to identify a walking partner within group (walk twice/week) |

None identified | 21 sedentary, hypertensive African American women ages 25 – 68 Mid-Missouri (Midwest) |

Steps per day – Accusplit Eagle pedometers | Total group experienced a slight increase in mean steps/day at 12 months (5%) Subgroup of 10 women had a decrease of 13% 6 month follow-up (mean steps increased by 37% for total group and 51% for subgroup |

Strengths: group-based intervention and objective measure (pedometer) for step count Limitations: no control group, convenience sample (may have had a desire to increase physical activity), sample size, and variable participation in individual data collection sessions |

| Befort, et al.,26 (2008) | Examine whether the addition of motivational interviewing to a culturally – targeted behavioral weight loss program for African American women | RCT 2 |

4 individual motivational interviewing sessions in addition to 16 week culturally targeted behavioral weight loss program 90-min weekly sessions | None identified | 44 African American women ≥ 18 years old BMI (30 – 50) Kansas City, Missouri (Midwest) |

CHAMPS – Physical activity questionnaire | Nonsignificant changes in physical activity | Strengths: randomized sample, culturally-targeted program |

| Christie et al.,43 (2010) | Examine efficacy of church-based community intervention in reducing obesity related outcomes in U.S. African American females | Single group, pre/post test 3 | 24 week intervention (12 weeks per phase) Sessions included 1 hour of physical activity and 1 ½ hour nutrition education, cooking demonstrations, and social support | None identified | 383 African American women >18 years old Wishing to lose weight | Physical activity self-reported (self-recorded daily minutes of exercise) | Exercise in minutes significantly higher from baseline to 12 weeks and baseline to 24 weeks (nonsignificant between 12 and 24 weeks) | Strengths: church-based, cultural components Limitations: single group design (no control group), eligible participants were wishing to lose weight (results not generalizable) |

| Duru et al.,17 (2010) | Evaluate faith-based intervention (Sisters in Motion) to increase walking in older, sedentary African American women | RCT, randomized by participant 2 |

90 minute weekly meetings for 8 weeks followed by monthly meetings for 6 months Two groups: intervention group received faith-based curriculum (evidenced based practice for physical activity programs targeting older adults) and 45 minutes of weekly physical activity, while control group received only 45 minutes of weekly physical activity |

SCT concepts | 62 sedentary, African American women ages 60 and over Mean age: 73.3 (intervention), 72.2 (control) 3 Los Angeles churches (Region: West) Intervention group had < 10% dropout rate and control group < 20% dropout rate |

Weekly steps – pedometer (Digiwalker Yamax SW-200) Physical activity – CHAMPS Physical Activity Questionnaire modified version for African Americans |

Six month follow-up – significant difference in steps (intervention group increase mean walking 7,457 (average) steps more than the control group) Overall physical activity in hours/week: not statistically significant |

Limitations: 8 week timeframe, Self-report physical activity |

| Fitzgibbon, Stolley, et al.27 (2005) | Determine if a combined breast health/weight loss intervention to could decrease weight and dietary fat intake and increase physical activity and breast self-exam proficiency | Randomized pilot 3 |

Small groups met twice weekly First 90 minute meeting included 45 minute didactic component and 45 minute exercise component Second weekly meeting consisted of 45 minute exercise session |

SCT | 27 African American women in cohort one 37 African American women in cohort two Region:Midwest |

Researcher developed physical activity questions | Cohort 1: nonsignificant results Cohort 2: significant changes in frequency of regular physical activity, duration of physical activity, and intensity of physical activity for the intervention group |

Strengths: Randomization: women in the two cohorts were randomized to the intervention or control group, culturally tailored intervention |

| Fitzgibbon, Stolley et al. (2005) | Estimate the effects of a 12 week culturally tailored, faith based, weight loss intervention | RCT 2 |

12 week intervention (faith-based weight loss intervention versus weight loss intervention) Small groups met twice weekly for exercise sessions and didactic session Faith-based intervention also included faith/spirituality components |

SCT | 59 overweight, African American women ≥ 21 Region:Midwest |

Stanford Seven-Day Physical Activity Questionnaire (7D-PAR) | Significant increase in total energy expenditure and energy expended in moderate and vigorous activity for the weight loss group. Nonsignificant changes for the faith-based weight loss group | Strengths: randomization, culturally tailored |

| Gaston, Porter, and Thomas11 (2007) | To evaluate effectiveness of Prime Time Sister Circles, a curriculum-based, culture and gender specific health intervention | Multisite, quasi-experimental 3 | Groups met for 90 minutes weekly for 10 weeks Facilitators led small group Goals were set related to nutrition, physical activity, and stress management Participants received a textbook and curriculum workbook Comparison group received a textbook |

SCT, Trans-theoretical Model (TTM), and Person, Extended Family, Neighborhood (PEN) | 134 African American women (106 – intervention group and 28 – comparison group) 11 sites across US including Illinois, Washington D C, Florida, and Maryland Ages: 35 and older (mean – 54.4) 4 out of 11 sites were churches < 20% dropout rate |

Physical activity - survey | Significant changes in physical activity from pretest to posttest Increased engagement in strength building (1.53, 2.53, and 2.45 – days/week at baseline, posttest, and 12 months follow-up) This increase did not remain for the 6 month follow-up No significant pretest and posttest change for the comparison group |

Strengths: small, group-based program; culture and gender specific theory-based intervention,. Limitations: self-reported physical activity, no randomization, and results may not be generalizable (primarily college-educated, middle income participants) |

| Gerber et al.,18 (2013) | Evaluate effect of home telehealth on weight maintenance after group-based weight loss program | RCT 2 |

Telephone counseling Home internet enabled digital video recorders with 3 channels for video content including exercise videos Maintenance phase lasted 9 months – included 60 minute weekly sessions didactic session |

88 obese or overweight African American women Ages: 35 to 65 Mean: 50 (intervention), 49 (control) Recruited from community Churches < 20% dropout rate Region:Midwest |

Physical activity – International Physical Activity Questionnaire – short version | Moderate to vigorous activity change was similar for both groups (p = 0.49) Moderate activity levels were better maintained in intervention group (p = 0.01) |

Strength: participants were randomized Limitations: Sample size, self-report physical activity, and 47% did not engage in DVR viewing |

|

| Joseph, Pekmezi, et al.37 (2014) | Evaluate a culturally relevant, social cognitive theory-based, Internet physical activity pilot intervention developed for overweight/obese African American female college students | Single group, pretest-posttest 3 | 3 month intervention consisting of four, 30 – 60 minute moderate-intensity walking/exercise sessions each week Internet based application for physical activity monitoring | SCT | 25 African American women Aged 19 to 30 BMI > 25 kg/m2 Undergraduate or graduate student | 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (7-Day PAR) Actigraph accelerometer | Nonsignificant changes in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from baseline to post intervention; participants overreported physical activity on the 7-Day PAR when compared to accelerometer data | Strengths: Majority of participants identified the internet site as ‘somewhat’ to ‘very helpful’ for promoting physical activity, culturally tailored Limitations: convenience sample, sample size, and lack of a control group |

| Joseph, Keller, Adams, & Ainsworth 42 (2015) | Evaluate a theory-based multi-component intervention using Facebook and text-messages to promote physical activity among African American women | Randomized pilot 2 | 8 week, Facebook and text-messaging intervention (weekly promotion materials posted on Facebook wall, discussion topics and participant engagement on Facebook wall, motivational text messages, and pedometer-based self-monitoring and goal setting | SCT | 29 African American women age 24 – 49 who were insufficiently active (< 150 minutes moderate-intensity activity per week) Region: West |

ActiGraph accelerometer Self-report physical activity | Nonsignificant changes from baseline to 8 weeks (accelerometer measured physical activity outcomes) Significant changes in light-intensity and moderate intensity physical activity between groups Significant change in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for Facebook intervention group |

Strengths: theory-based, culturally tailored, participants randomized Comparison group received print based materials every two weeks for 8 weeks |

| Karanja et al.,44 (2002) | Test the effects of a culturally adapted weight loss program in weight loss in African American women | Pilot Single, arm pre-post 3 | 6 month weight loss program; weekly group meetings and supervised exercise sessions at a local community center Group participants shared low-fat meals prepared by participants |

None identified | 66 African American women (3 dropped out after 3 group sessions) | Exercise (hours per week) – self-reported | Significant increase in exercise - 6 months average hours of exercise/week doubled from baseline | Strength: cultural adaptations (social support, African American instructors/leaders, and involved family/community) Limitation: no control or comparison group |

| Keyserling et al.,19 (2002) | To determine if culturally appropriate clinic and community-based intervention for African American women with type 2 diabetes will increase moderate-intensity physical activity | RCT (3 intervention groups) 2 |

Group A – clinic and community-based Group B-clinic intervention only Group C – minimal intervention (were mailed pamphlets published by American Diabetes Association) |

Behavior change theory (TTM & SCT) | 200 African American women ages 40 and older with type 2 diabetes Mean age: 59 Region: South |

Physical activity – Caltrac accelerometer | Overall significant change in physical activity at 6 months and 12 months follow-up for all groups Significant difference in change in physical activity between group A and C at 6 and 12 months Significant difference in change in physical activity between group B and C at 6 months |

Strengths: participants were randomized, increased participation rates for follow-up, objective physical activity measure, and intervention was acceptable to participants Limitations: intervention had different actual Caltrac wearing times (potential for bias) |

| Liu et al.,32 (2014) | Test feasibility and participant satisfaction of theory-based nutrition and physical activity intervention designed to prevent excessive gestational weight gain and promote postpartum weight loss in overweight and obese African American women | Mixed – methods Phase 1: Qualitative (in-depth interviews) Phase 2 – intervention utilizing findings from phase 1 3 |

Behavior intervention program included individual counseling session followed by 8, 90 minute group sessions. Group sessions led by African American research staff member Telephone counseling contacts continued through 36 weeks gestation Post-partum: participants received home visit and up to three counseling calls |

SCT | 16 overweight and obese, pregnant, African American women Mean age: 25.1 (intervention), 27.4 (control) Contemporary controls (n = 38) were selected from medical records – pregnant women who met same criteria as study participants Columbia, South Carolina |

Physical activity – SenseWear Armband | Steps/day were similar at baseline and 32 weeks gestation Steps/day significantly increased from baseline to postpartum Significant increase in total energy expenditure at 32 weeks gestation and 12 weeks postpartum Significant increase in total minutes spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity (baseline vs. 12 weeks postpartum) |

Strengths: theory-based intervention, intervention tailored to study population, and objective physical activity measure Limitation: sample size and contemporary controls (outcome measures based on baseline, 32 weeks gestation, and 12 weeks postpartum for intervention group only) |

| Montgomery31 (2009) | To determine use of pedometers to increase walking (physical activity) in African American women who were between 6 weeks to 6 months post-partum | Correlational study 3 |

Women wore pedometers daily for 12 weeks (except for bedtime and bathing) Structured physical activity program |

Not clearly stated | 31 sedentary, postpartum, African American women ages 18 to 40 (mean – 29.58) South central region of Alabama 31 out of 32 completed the study | Step count – Yamax Digiwalker SW-200 | Significant difference in average steps/day pre-post study 63.6% increase in average number of steps taken/day over 12 week period |

Limitation: homogenous group of women (limits generalizability) |

| Parra-Medina et al.,20 (2011) | Evaluate theory-based lifestyle intervention targeting physical activity and dietary fat intake in African American women at high risk for cardiovascular disease | RCT 2 |

Culturally appropriate, theory based intervention included telephone calls and printed materials 12 motivational, stage matched ethnically tailored newsletters and up to 14 calls over 1 year Comprehensive intervention group and standard care group |

SCT and TTM | 266 low-income African American women ages 35 and older South Carolina community health centers 43% attrition rate at 12 months |

Self-reported minutes/week of moderate to vigorous physical activity CHAMPS (Community Health Activities Model Program for Seniors) – 41 item questionnaire |

Comprehensive intervention participants were more likely than standard care participants to decline in total physical activity at 6 months Comprehensive intervention group significantly more likely to improve in leisure-time physical activity at 6 months |

Strengths: theory-based intervention, participants were randomized, and culturally tailored intervention Limitations: no true no-treatment control, attrition rate (43% at 12 months), and self-report physical activity data |

| Pekmezi et al.,41 (2013) | Determine feasibility and acceptability of home-based physical activity intervention | Mixed – methods Qualitative (focus groups) and single-arm pre-posttest demonstration trial 3 |

One month trial – participants receive motivation-matched physical activity manuals and individually tailored computer expert system feedback reports through mail Pedometers were given to encourage self-monitoring | SCT and TTM | 11 Focus groups in Alabama and Mississippi 6 African American women per group) Trial – 10 overweight, African American women ages 19 – 65 from Alabama (mean 39.1 years) 90% retention |

Physical activity – 7 day PAR (primary outcome measure) 6 minute walk test |

Participants reported increase in moderate intensity or greater physical activity from 89 minutes/week (baseline) to 155 minutes/week 70% of participants reported increased motivational readiness for physical activity at 1month Small, nonsignificant improvements in fitness (6 minute walk test) |

Strengths: intervention grounded in theory and intervention modified based on focus group data Limitations: no control group, sample size, and results may not be generalizable (all participants had some college education) |

| Peterson and Cheng39 (2011) | Test feasibility of church-based Heart and Soul Physical Activity Program (HSPAP) in promoting physical activity in group of urban midlife African American women | Pilot study 3 |

HSPAP booklet revised for African American women 2 hour weekly session for 6 weeks included 30 minutes of physical activity Sessions were held at their church and facilitated by an African American nurse practitioner |

Social comparison theory | 18 midlife, sedentary, African American women Age: 35 to 65 Large, Midwestern city |

Physical activity (time and intensity) measured by self-report (7 DAR) Triaxial Research Tracker (RT3) accelerometer for 1 week at baseline and 5 weeks |

Total minutes of physical activity/week increase significantly (7 DAR data) Mean increased from 412 minutes/week to 552 minutes/week Nonsignificant increase in physical activity although physical activity intensity increased from 3.33 METS to 4.33 METS |

Strengths: high correlation between 7 DAR and accelerometer, church-based program and study based on qualitative focus group analysis Limitations: sample size, 6 week timeframe, no control group, and did not evaluate long-term changes |

| Rimmer et al.,36 (2010) | Examined effectiveness of telephone-based intervention to increase physical activity in obese African American women with disabilities | Pilot study 3 |

Weekly calls for 6 months (discussion of current health issues and new/persistent barriers to physical activity, motivational interviewing utilized) | 33 sedentary, obese, African American women with mobility disabilities Age: > 18 years (mean-60.1) Mid-western United States 33 out of 53 retained |

Physical activity measured by Physical Activity and Disability Survey Barriers to Physical Activity and Disability Survey |

Significant increase in total minutes/day of structured exercise, general indoor household physical activity, and total physical activity | Limitations: participants were volunteers (may have already been motivated to increase physical activity), no control group, and no theory stated for intervention | |

| Scarinci et al.,21 | Examine efficacy of community-based, culturally relevant intervention to promote healthy eating and physical activity among 45 – 65 year old African American women | Cluster RCT 2 |

2 arms

|

SCT and TTM Community-based participatory research |

565 African American women Age: 45 to 65 (mean – 53.9) 6 counties in Alabama 60.9% retention at 12 months 54.7% retention at 24 months |

Engagement in physical activity at least 5 times/week measured by a questionnaire | Significant change in physical activity between two arms 12 month follow-up – 24% increase in physical activity (healthy lifestyle group) and 3% increase for screening group |

Strengths: RCT, community-based participatory research Limitations: two interventions (lifestyle and screening), difference in retention rates between two arms, and self-reported physical activity |

| Spector et al.,33 (2014) | Determine if 16-week home-based motivational exercise study increases physical activity levels | Prospective, single arm Pretest/post-test 3 |

Home-based exercise intervention initially low-intensity walking and resistance training that progressed to 150 minutes/week low to moderate intensity exercise Weekly telephone motivational interviewing sessions Therabands were provided for resistance exercises Pedometers provided to help motivate participants to walk |

None identified | 13 sedentary, African American women breast cancer survivors Age: ≥ 18 (mean – 51.6) |

Physical activity – accelerometer and International Physical Activity Questionnaire – short version | Significant increase in total minutes/week of physical activity (questionnaire data) Significant increase in mean activity counts and moderate to vigorous activity (accelerometer data) Questionnaire total activity was positively correlated with accelerometer counts at 3 time points (p < .001) |

Strength: objective physical activity measure Limitations: no control group, sample size, and recruitment (self-selection) – participants may have already been motivated to increase physical activity) May not be able to generalize – all participants had some level of college education |

| Staffileno et al.,22 (2007) | Examine blood pressure effects of integrating lifestyle physical activity into daily routine of hypertension prone, sedentary African American women ages 18 – 45 | Randomized parallel group, single blind clinical trial 2 |

8 week individualized home-based physical activity program Exercise group instructed to engage in lifestyle physical activity for 10 minutes, three times/day, five days/week at a prescribed intensity of 50–60% heart rate reserve 60 minute education session Physical activity log (mode, frequency, duration, and heart rate) |

24 African American women with high-normal (130–139 mm Hg/85–89 mm Hg) or untreated, stage 1 hypertension (140–159 mm Hg/90–99 mm Hg) Age: 18 to 45 (mean – 39 years) 96% post-randomization retention Region: Midwest |

Physical activity – Yale Physical Activity Survey Physical activity and physical activity adherence - physical activity logs (reviewed weeks 2, 4, 6, & 8) |

High lifestyle physical activity adherence – ranged from 65 to 98% Self-reported frequency (72%) and duration (87%) Significant increase in self-reported energy expenditure in exercise group |

Strengths: randomization, blinded clinical outcome measures, individually tailored intervention Limitations: 8 week timeframe, self-report physical activity, and sample size |

|

| Stolley et al.,34 (2009) | Examine feasibility and impact of Moving Forward, culturally tailored weight loss program for African American breast cancer survivors | Pre/post design 3 |

6 month comprehensive weight loss intervention designed for urban African American breast cancer survivors Intervention included 2 weekly sessions including an exercise class Participants received exercise DVDs for at-home use |

SCT and Health Belief Model | 23 African American women who were breast cancer survivors Age: ≥ 18 Chicago 20 out of 23 completed study |

Physical activity measured by International Physical Activity Questionnaire – long version | Significant increase in median time spent in vigorous activity (0 minutes/day at baseline to 23.6 minutes/day) Although changes were nonsignificant, time spent in moderate activity and in all physical activity increased |

Strengths: theory-based, culturally appropriate, and qualitative data utilized to develop intervention Limitations: physical activity self-reported, sample size, no control group, and self-selection for participation (potential for bias) |

| Stolley, Fitzgibbon et al.,15 (2009) | Assess efficacy of a culturally proficient 6 month weight loss intervention | RCT 2 |

Twice weekly nutrition & PA sessions included didactic and physical activity | SCT | 213 obese, black women Age: 30 – 65years BMI (30 – 50) retention (93.5%-intervention group; 92.5%-control group) Chicago |

International Physical Activity Questionnaire | Intervention group reported significantly more vigorous and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity than the control group Self-reported walking differences (intervention and control group) nonsignificant |

Strengths: small group format for sessions, designed for black women (culture), randomized, high retention Limitations: self-report data |

| Wilbur et al.,40 (2008) | Determine effectiveness of home-based walking intervention, compared to minimal treatment, on adherence, physical activity, fitness, and body composition at 24 and 48 weeks | Quasi-experimental 2 |

12 month intervention trial with 24 week intensive adoption phase and 48 week maintenance phase Enhanced treatment (intervention) – 4 weekly, 60 minute targeted workshops and tailored weekly phone calls for weeks 5 to 7, every other week phone calls for weeks 10 to 22 and monthly calls for weeks 25 to 48 | Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior | 156 (enhanced treatment) and 125 (minimal treatment) sedentary, midlife African American women ages 40 to 65 | Adherence to walking – heart rate monitors and logbook (for both groups) Physical activity - BRFSS |

Including only women who had adherence data at 24 months and 48 months, significant group difference in walking adherence for 24 and 48 weeks No significant difference in walking intensity between groups Both groups had significant improvements in meeting physical activity recommendations at 24 and 48 weeks |

Strengths: randomization, culturally appropriate (feedback from African American in focus groups from previous study), and low-income and moderate-income women were included Limitations: self-report physical activity |

| Wilbur et al.,29 (2003) | Identify determinants of physical activity among African American and Caucasian women that predict adherence to 24 week home-based walking program | Pre-Post intervention 3 |

Moderate-intensity 24-week home-based walking program Personal exercise prescription, instructional and support from nurse research team member who met with each woman every 2 weeks for reinforcement and feedback on progress 96 walks expected (4/week) |

Adapted Cox Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior | 153 women (33 African American, 67 Caucasian) Age: 45 to 65 (mean – 49.8) Location not specifically stated |

Previous exercise experience measured by leisure dimension of Lifelong Physical Activity measure (activity measured in 10 year increments starting at age 20) | Average adherence was 66.5% of expected walks (range 6 to 104%) Adherence was higher for Caucasian women than for African American women (71.5 mean, 56 mean respectively) Greater than 90% adherence to both duration and intensity | Limitation: Most of sample were higher SES |

| Wilson et al.,35 (2005) | Test feasibility and impact on steps/day and BMI for theory-based, cognitive behavioral walking program | Pilot study 3 |

8 week community-based walking program (75 minute sessions at community center in evening and church around noon) Sessions included didactic, interactive, and small group processes | Health Belief Model | 24 African American women who were breast cancer survivors Age: < 70 years old Urban inner city setting (Region: West) 22 out of 24 completed intervention |

Step count - pedometers | Statistically significant difference in steps/day (baseline, immediate post-intervention, and 3 month follow-up) Significant increase in mean steps (4791 to 8297) Change in steps/day from post-intervention to 3 month follow-up were nonsignificant |

Strengths: Theory-based, cognitive-behavioral intervention and study’s goal was for participants to integrate walking into their routine on their own Limitation: no control group |

| Yancey et al.,23 (2006) | Test efficacy of 8-week culturally targeted nutrition and physical activity intervention on body composition | RCT with attention control condition 2 |

Both groups received 8 weekly 2 hour sessions with ethnically matched community role models as guest instructors | Social Ecological Model | 389 African American women within 10-mile radius of health club Mean age: 46.52 (control), 44.56 (intervention) Ethnically diverse, black-owned community center 70% retained at 12 month follow-up Region: West |

Physical activity measured by 4-item scale Cardiorespiratory fitness | Significant increase in physical activity levels from baseline for intervention participants (p < 0.0001 @ 2months) p = 0.04 @ 6 months Significant main effect of the intervention on physical activity (p = 0.0148 at 2 months and p = 0.058 at 12 months) Significant main effect on fitness at 2 months (nonsignificant at 6 or 12 months) |

Strengths: RCT with attention control condition Free gym membership provided |

| Yanek et al.,25 (2001) | Determine impact of active nutrition and physical activity intervention on one year measures relating to lifestyle risk factors and CVD risk profiles | Randomized clinical trial 2 |

3 intervention strategies:

|

Social learning theory Based on community action and social marketing model |

16 African American churches (529 women) Age: ≥ 40 years old Mean: 53.6 (spiritual), 51.9 (standard), 53.9 (self-help group) 56% completed one year follow-up biological measures (67.7% of them completed all measures including physical activity) Region: South |

Physical activity measured by Yale Physical Activity Survey | Based on self-report, energy expenditure increased for intervention groups (near significant change) No differences between standard and spiritual group |

Strengths: Church-based Limitations: self-report physical activity |

| Young and Stewart (2006) | Determine whether aerobic exercise intervention would increase daily levels of energy expenditure and decrease prevalence of physical inactivity compared to stretching and health lecture intervention | Prospective, randomized trial 2 |

1 hour weekly aerobic exercise class for 6 months Other group received stretching and health lecture intervention |

SCT | 11 churches were randomized Age: 25 to 70 Intervention group - 123 African American women (5 churches) – mean age:48.2 Control (intervention group 2) – 73 African American women (6 churches) – mean age: 48.4 Region: South |

Level of physical activity – Stanford 7 Day Physical Activity (PAR), Yale Physical Activity Survey (YPAS) Cardiorespiratory fitness – peak oxygen uptake |

No significant difference between groups for physical activity Sample size too small at follow-up to analyze cardiorespiratory fitness level |

Strengths: Both intervention groups were grounded in theory Group-based/church-based program (one church continued classes after study ended) Limitations: Low program attendance, Low return for follow-up measures, two intervention groups (control group was not utilized due to feedback from pastors) |

Data Analysis, Presentation

Studies included in this review are presented in Table 1 with the following column headings: purpose, design, intervention, theoretical framework, sample/location, physical activity measure, physical activity outcomes, and strengths/limitations.

RESULTS

Results identified in this review include significant and nonsignificant changes in PA. Thirty-one studies focused solely on African American women. One study included non-Hispanic White and African American women, with results reported separately for each racial group.29

Sample description

The patient populations across the studies were heterogeneous, and included low-income women30, postpartum31, pregnant32, breast cancer survivors33–35, type 2 diabetes19, mobility disabilities36, and women with high-normal or untreated stage 1 hypertension.22 Common inclusion criteria included overweight or obesity 15,18,26,32,34,36,37 and sedentary.17,22,29,31,33,36,38–40 Few studies focused on women who were age 40 or older19,25 and age 60 or older.16,17

Theoretical Framework

Twenty-two of the 32 studies included in this review relied upon a theoretical framework 11,14–17,19–21,23–25,27,29,30,32,34,35,37,39–42 with all reporting significant or mixed results, with the exception of two studies reporting nonsignificant changes in PA24,25 The most commonly used theory identified was the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), either used alone15,17,24,27,30,32,42,14,37 or in combination with another theory.11,20,21,34,41 Several studies did not report using a theory-based intervention however, significant changes in results were reported including an increase in total minutes of physical activity,33,36,43 increase in steps per day, 31,38 and self-reported energy expenditure.22 Several concepts identified in the intervention strategies included goal-setting,11,16,17,20,22,24,26,32,33,36,39–41 reinforcement,17,32 and problem-solving.22,26,32,35,36,40,41 Self-monitoring of PA22,26,32,37,41 and PA barriers26,36 were identified as intervention strategies. Notably, both theoretical and atheoretical studies reported significant and mixed results.

Intervention Strategies

Intervention strategies included culturally tailored interventions, faith-based interventions, group-based programs, and individually tailored programs. Furthermore, strategies included face-to-face sessions, telephone sessions, a combination of face-to-face and telephone sessions, and peer support.

As in the previous review by Banks-Wallace and Conn,10 several studies described culturally tailored interventions. Culturally tailored interventions will refer to studies that tailored the intervention to African American women. Many studies 11,15,19–21,23,26,27,37,40,42–44 reported culturally tailored interventions cited in prior research or focus group findings that were incorporated into the design of the intervention strategies. Several studies were led by ethnically matched individuals.24,25,32,39,43,44 Additional culturally tailored strategies identified include adapting educational materials and sessions for African American women, choice of location,43,44 and social support.24,26,39,43,44. Across studies using a culturally tailored intervention, significant results11,19–21,43 mixed results23,27,40–42, and nonsignificant results26,37 were reported.

Faith-based settings are commonly used as research intervention delivery sites.10 However, similar to the previous review by Banks-Wallace and Conn;10 few faith -based studies were found. Three studies24,43,45 were conducted in faith settings however these studies did not include a faith intervention. Studies conducted in a faith setting reported significant,43 nonsignificant,24 and mixed45 results. Five studies14,16,17,25,39 were faith-based interventions. Faith-based intervention strategies included health information messages that were relayed by the pastor,25 faith community nurse,16 prayers,16,17,25 Bible messages on holistic wellness,39 and Bible scriptures.14,16,17,25 Faith-based intervention studies reported results that were mixed16,17,39 and nonsignificant.14,25

The majority of the studies included an educational or instructional component. Several studies11,14,17,18,21,24,25,27,34,38,39,43–45 included group exercise sessions. This review revealed that several studies included a group meeting or educational session. 11,14,17–19,21,24,25,27,32,34,38–40,43–45 Across home-based18,29,33,40,41 and telephone-based36 studies, significant and nonsignificant results were reported. Another strategy identified, were phone calls from a peer counselor or research staff member.18–20,31–33,36,40 Motivational interviewing was used as a strategy in several studies.20,26,33,36 Peer support was a component of several intervention strategies by including a walking or exercise partner.23,24,31,38 Table 1 provides additional information regarding PA interventions. Table 2 includes strategies from selected studies that reported significant changes in PA.

Table 2.

Selected intervention strategies providing significant increases in physical activity

| Intervention strategy | |

|---|---|

| Theory-Based | Included Social Cognitive Theory concepts - Intervention group received six, one-hour toolbox classes (one session/week) focusing on fruit/vegetable consumption and physical activity30 8 week community-based walking program (75 minute sessions at community center in evening and church around noon) based on the Health Belief Model Sessions included didactic, interactive, and small group processes35 |

| Culturally Tailored | 24 week intervention (12 weeks per phase) - Sessions included 1 hour of physical activity and 1 ½ hour nutrition education, cooking demonstrations, and social support – Culturally tailored intervention included ethnically matched program staff, peer leaders/health coordinators recruited from each church, and the intervention was held in a church setting43 6 month weight loss program focused on nutrition and physical activity; weekly group meetings and supervised exercise sessions at a local community center – Culturally tailored intervention included: participants chose the location and format of exercise sessions, participants chose the content of group meetings, ethnically matched program staff, social support, and group participants shared low-fat meals prepared by participants (participants also discussed how they reduced fat content for each meal)44 |

| Theory-Based & Culturally Tailored | Culture and gender specific intervention based on TTM, SCT, and the PEN model. Facilitators led small groups that met for 90 minutes weekly for 10 weeks. Majority of facilitators were African American women. Goals were set related to nutrition, physical activity, and stress management. Participants received a textbook and curriculum workbook. Comparison group received a copy of the textbook provided to the intervention group. Diabetes intervention program “New Life….Choices for Healthy Living with Diabetes” focused on nutrition, physical activity, and self-care behaviors and based on the Transtheoretical Model and Social Cognitive Theory. Clinic-based intervention consisted of four clinic visits. Community-based intervention consisted of 12 telephone contacts with a community diabetes advisor and three group sessions. Three groups (group A, B, and C) : Group A – clinic and community-based, group B-clinic intervention only, and group C – minimal intervention (were mailed pamphlets published by American Diabetes Association) African American women with type II diabetes participated in focus groups to evaluate cultural aspects of the program19 Theory-based (SCT) nutrition and physical activity behavior intervention included individual counseling session followed by 8, 90 minute group sessions. Telephone counseling contacts continued through 36 weeks gestation. Post-partum: participants received home visit and up to three counseling calls. Culturally tailored - Group sessions co-led by African American research staff member Culturally tailored, theory based (TTM & SCT) intervention included telephone calls and printed materials that addressed topics of concern for African American women. Intervention also included 12 motivational, stage matched ethnically tailored newsletters and up to 14 calls over 1 year20 Healthy lifestyle focusing on nutrition and physical activity (intervention was adapted from the “New Life….Choices for Healthy Living with Diabetes”19 5 week healthy lifestyle intervention included 4 group and 1 individual session21 Theory-based (SEM), culturally tailored nutrition and physical activity intervention included 8 weekly 2 hour sessions with ethnically matched community role models as guest instructors. Intervention also included skills training in a balanced regular exercise regimen, nutrition education focusing on a low-fat, complex carbohydrate-rich diet, social support, and incentives. Participants received a one-year free gym membership and were able to invite one family member or friend to receive a one-year free membership as well (social support). Incentives included pedometers and exercise bands 23 |

Physical Activity Measures

Physical activity measures included self-report, pedometers, accelerometers, heart rate monitors, and an armband with accelerometer and galvantic skin response (i.e. SenseWear). The most common objective measures were pedometers17,31,35,38 and accelerometers. 19,33,37,39,42 Nine studies included both objective and self-report measurements.17,23,24,33,37,39–42 This review revealed that self-report measures of PA are more commonly used, with only 14 of the 32 studies using an objective measure. The majority of studies using an objective measure reported significant results. Although self-report measures provided significant and nonsignificant results, future studies using self-report measures should include an objective measure as well. For example, a faith-based, pilot study39 reported significant, self-reported results although an objective measure provided nonsignificant results. Table 1 provides information regarding the various self-report measurements.

Physical Activity Outcomes

Majority of the studies did not include a follow-up period or measure outcomes beyond the intervention. Of the 32 studies, 28 reported significant results in at least one outcome. Although several studies reported significant results for one measure, nonsignificant results for another measure were reported. This finding is similar to the previous review10, with mixed results of interventions promoting PA in African American women. Significant results were reported for muscle strengthening activities16, 6-minute walk test16, steps17,30,31,34, total minutes of PA, 32,35,39 changes in PA17,19,21, time spent in PA32,36,39 and time spent in leisure time PA20 and vigorous activity.34 Other studies reported nonsignificant results for overall PA hours per week17, moderate to vigorous activity18, PA intensity39 and walking intensity.40 Total daily expenditure of energy was significant for two studies22,32 and nonsignificant for two studies.16,25 Although weight loss was not the focus of this review, studies reported significant weight loss (based on BMI and/or weight)15,23,25,31,34,35,43 and nonsignificant difference in weight.17,18,33 This review reveals mixed findings for changes in PA with several studies indicating significant changes and other studies reporting nonsignificant findings. Table 1 provides additional information for measures and outcomes in this integrative review.

DISCUSSION

Increasing PA is important for all populations; however, intervention strategies that promote PA in African American women are essential because African American women have the highest rate for physical inactivity and obesity in the US. Increasing PA in African American women is a crucial component to reducing the prevalence of chronic health conditions. This review provides insight into the current state of the science focusing on intervention strategies that promote PA in African American women.

Older adults are more likely to not meet PA guidelines when compared to younger adults.4,46 In a 2011 report,46 only 15.9% of older adults (65 years and over) met aerobic and muscle-strengthening guidelines. Older African American women tend to have a lower level of PA.16,17 Most studies promoting PA in African American women have primarily focused on young and middle aged women.10 This review revealed a dearth of PA interventions focusing on older African American women. Several studies included age ranges that included women through age 65 or 70; however, only two studies16,17 specifically focused on women age 60 or older. Both studies reported significant findings including change in steps17 and changes in muscle-strengthening activity16 and nonsignificant findings for change in overall PA or total daily energy expenditure, based on objective and self-report data. One study16 reported a significant difference in muscle strengthening activity and a nonsignificant difference for moderate PA or total daily expenditure. The other study17 focused on strategies to increase walking and reported a significant increase in steps, yet nonsignificant for overall PA in hours per week. Increasing both aerobic activity and muscle-strengthening is important for older African American women and older adults in general.

The use and benefit of interventions utilizing a theoretical framework are mixed. The review by Banks-Wallace and Conn10 revealed an infrequent use of theoretical frameworks, which are essential to intervention studies.47 Theoretical frameworks have been emphasized as integral to behavioral and health science research to guide intervention design and evaluation. 47 This review revealed various theoretical frameworks that were utilized in PA interventions for African American women. In addition to theoretical frameworks, culturally tailored interventions should be considered.11 Interventions that are culturally tailored increase acceptability by participants.11 Majority of culturally tailored interventions reported significant or mixed changes in PA.

This review revealed promising PA intervention strategies for increasing PA in African American women. As with the previous review,10 intervention components included problem-solving, social support, goal setting, and group exercise. These intervention components have been identified as effective ways to increase PA.10,29 Despite faith-based settings being a commonly used site for interventions,10 few studies in this review were identified as a faith-based setting or faith-based intervention. Notably, mixed results were reported for faith-based interventions and studies held in faith-based settings. Faith communities have the potential to influence the health of African American women39, particularly for those who consider their faith to be an important part of their life.16,17 Future faith-based intervention and faith-based setting studies are warranted. In addition to faith-based intervention studies, group-based and individually tailored interventions were identified. Various barriers to PA for African American women have been reported including costs, childcare/caregiving, lack of safe places to exercise, hair maintenance, and lack of time. 11,41,48 Home-based programs are a promising approach to increase PA while also eliminating several potential PA barriers. Home-based programs included in this review yield mixed-results18,40,41 and significant changes in PA33 and PA adherence.29

PA outcomes were most commonly measured by self-report. Moreover, various measurements of PA were included in the review. PA measures included self-report questionnaires and objective measures such as pedometers, accelerometers, 6-minute walk test, and 1 study that utilized SenseWear Armbands. Objective measures may decrease the rate of errors, specifically the potential to report inaccurate PA levels with self-report questionnaires. Objective measures may also influence behavior change. For example, research indicates that pedometers help to increase physical activity.49

Participants reported that increasing PA was the most difficult behavior change.11 However, despite difficulty of behavior change several studies reported high participant satisfaction.19,34,35,41 This review identified a diversity of study designs, interventions, and outcomes. Several findings should be cautiously considered due to their lack of a randomized control design or a comparison group.11,20,31,33–36,38,39,41,43,44 Several studies utilized a single arm pre-post design29,33,34,37,38,41,43,44 or quasi-experimental design.11,30,40 In addition, several studies included a small sample size.16,18,22,32–35,38,39,41 Future studies should include a randomized controlled design and objective PA measures. Examining participation rates beyond the study would be an important consideration for future studies. Although several studies report significant results, additional studies focusing on long-term PA maintenance are warranted. Most studies in this review did not include a follow-up period beyond the post intervention measurements. Of the nine studies that included a follow-up period for measurements, low return for follow-up was identified as a limitation in two studies.24,25 One study15 reported significant differences in vigorous and moderate PA at 6 months for the intervention and control group however, at 18 months PA results were nonsignificant.50

Limitations

This review does not include abstracts, dissertations, or studies referenced in other databases. A second limitation is the limited number of studies that focused on older African American women. As with the previous review, small sample size was a common limitation. Additional limitations include the use of self-report measures by most studies and the exclusion of indirect measures of PA including BMI and weight. However, this review focused on direct measures of PA. Indirect measures of PA such as BMI and weight may be influenced by dietary behaviors as well as PA,10 therefore, indirect measures were not a search criteria for this review.

Future Implications/Conclusion

Sixteen of the 32 studies included in this review focused on PA only, while the other studies focused on PA and nutrition. Many studies did not include follow-up measures. Future studies that include measures beyond the immediate post-intervention measurement are warranted. Many studies included self-report data that may be affected by measurement errors, e.g., PA over reporting. Thus, also warranted are future studies using objective measures entirely or studies that combine self-reports with objective measurements. Moreover, future studies including larger sample sizes, randomization, and control groups are needed. Since the Banks and Wallace10 review, intervention studies promoting PA focusing solely on African American women have increased. This integrative review provides important findings regarding the current state of science for interventions promoting PA within this specific population. Although more PA promotion research is occurring with this population, additional research is warranted. Intervention strategies have the potential to increase PA in African American women and reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease and other chronic health conditions. Nurses, in particular cardiovascular nurses, may use these findings to improve the quality of existing practices and to generate future research. Cardiovascular nurses, as well as other healthcare providers, may use this review to identify intervention strategies that will promote PA in African American women.

Physical inactivity is an important modifiable risk factor for obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic health conditions. Intervention strategies that promote PA in African American women are essential to reduce the risk of these preventable health conditions and to reduce health disparities. Many studies in this review revealed promising results. Further studies are needed to evaluate long-term outcomes and sustainable methods for PA behavior change.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank John Dinolfo, PhD, Center for Academic Excellence & Writing Center, Medical University of South Carolina, for his support and editing of this article.

Funding Statement

Dr. Carolyn Jenkins is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (Grant # R15 NR009486) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Grant # U58 DP001015 and # U50 DP422184) and Dr. Magwood is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (Grant # K01 NR013195) and National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant # R34 DK097724). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research, or National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Contributor Information

Felicia Jenkins, Email: jenkinf@musc.edu, Senior Nursing Instructor, University of South Carolina Upstate; Doctoral Student, Medical University of South Carolina, College of Nursing, 99 Jonathan Lucas St. Charleston, SC 29425, (864) 503-5412.

Carolyn Jenkins, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina.

Mathew J. Gregoski, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina.

Gayenell S. Magwood, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization [WHO] Physical activity. 2014 http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. 2014 http://healthypeople.gov/2020/about/tracking.aspx.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/health/index.html.

- 5.Eckel R, Jakicic J, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC Guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S76–S99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Women and Heart Disease Fact Sheet. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fs_women_heart.htm.

- 7.Heron M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2010. 2013;62 (6):1–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SH, Im E. Ethnic differences in exercise and leisure time physical activity among midlife women. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(4):814–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office of Minority Health [OMH] Obesity and African Americans. 2012 http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?ID=6456.

- 10.Banks-Wallace J, Conn V. Interventions to promote physical activity among African American women. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(5):321–335. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaston MH, Porter GK, Thomas VG. Prime Time Sister Circles: evaluating a gender-specific, culturally relevant health intervention to decrease major risk factors in mid-life African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(4):428–438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittemore R, Knafl KA. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):6–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Ganschow P, et al. Results of a faith-based weight loss intervention for black women. Journal Of The National Medical Association. 2005;97(10):1393–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML, Schiffer L, et al. Obesity Reduction Black Intervention Trial (ORBIT): Six-month Results. Obesity (19307381) 2009;17(1):100–106. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson K, Pullen C. Physical activity with spiritual strategies intervention: A cluster randomized trial with older african american women. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2013;6(1):11–21. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20121203-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duru OK, Sarkisian CA, Leng M, Mangione CM. Sisters in motion: a randomized controlled trial of a faith-based physical activity intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1863–1869. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber BS, Schiffer L, Brown AA, et al. Video telehealth for weight maintenance of African-American women. J Telemed and Telecare. 2013;19(5):266–272. doi: 10.1177/1357633X13490901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keyserling TC, Samuel-Hodge CD, Ammerman AS, et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve self-care behaviors of African-American women with type 2 diabetes: impact on physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(9):1576–1583. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parra-Medina D, Wilcox S, Salinas J, et al. Results of the heart healthy and ethnically relevant lifestyle trial: a cardiovascular risk reduction intervention for African American women attending community health centers. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1914–1921. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scarinci IC, Moore A, Wynn T, Cherrington A, Fouad M, Li Y. A community-based, culturally relevant intervention to promote healthy eating and physical activity among middle-aged African American women in rural Alabama: Findings from a group randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. (0) doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staffileno BA, Minnick A, Coke LA, Hollenberg SM. Blood pressure responses to lifestyle physical activity among young, hypertension-prone African-American women. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22(2):107–117. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yancey AK, McCarthy WJ, Harrison GG, Wong WK, Siegel JM, Leslie J. Challenges in improving fitness: results of a community-based, randomized, controlled lifestyle change intervention. J Women’s Health. 2006;15(4):412–429. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young DR, Stewart KJ. A church-based physical activity intervention for African American women. Fam Community Health. 2006;29(2):103–117. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, Gittelsohn J, Koffman DM. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Rep. 2001;116 (Suppl 1):68–81. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Befort CA, Nollen N, Ellerbeck EF, Sullivan DK, Thomas JL, Ahluwalia JS. Motivational interviewing fails to improve outcomes of a behavioral weight loss program for obese African American women: a pilot randomized trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(5):367–377. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzgibbon M, Stolley M, Schiffer L, Sanchez-Johnsen L, Wells A, Dyer A. A combined breast health/weight loss intervention for Black women. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(8):e1–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilbur J, Miller AM, Chandler P, McDevitt J. Determinants of physical activity and adherence to a 24-week home-based walking program in African American and Caucasian women. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26(3):213–224. doi: 10.1002/nur.10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Backman D, Scruggs V, Atiedu AA, et al. Using a toolbox of tailored educational lessons to improve fruit, vegetable, and physical activity behaviors among African American women in California. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;42(4S2):S75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montgomery VH. Physical activity and weight retention in postpartum black women. Journal of the National Society of Allied Health. 2009;6(7):6–17. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, Wilcox S, Whitaker K, Blake C, Addy C. Preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy and promoting postpartum weight loss: a pilot lifestyle intervention for overweight and obese african american women. Matern Child Hlth J. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1582-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spector D, Deal AM, Amos KD, Yang H, Battaglini CL. A pilot study of a home-based motivational exercise program for African American breast cancer survivors: clinical and quality-of-life outcomes. Integ Cancer Ther. 2014;13(2):121–132. doi: 10.1177/1534735413503546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Oh A, Schiffer L. A weight loss intervention for African American breast cancer survivors, 2006. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2009;6(1):A22–A22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson DB, Porter JS, Parker G, Kilpatrick J. Anthropometric changes using a walking intervention in African American breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2005;2(2):A16–A16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rimmer JH, Hsieh K, Graham BC, Gerber BS, Gray-Stanley JA. Barrier removal in increasing physical activity levels in obese African American women with disabilities. J Women’s Health. 2010;19(10):1869–1876. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph RP, Pekmezi D, Dutton GR, et al. Results of a Culturally Adapted Internet-Enhanced Physical Activity Pilot Intervention for Overweight and Obese Young Adult African American Women. Journal Of Transcultural Nursing: Official Journal Of The Transcultural Nursing Society / Transcultural Nursing Society. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1043659614539176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banks-Wallace J, Conn V. Changes in steps per day over the course of a pilot walking intervention. The ABNF Journal: Official Journal Of The Association Of Black Nursing Faculty In Higher Education, Inc. 2005;16(2):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterson JA, Cheng A-L. Heart and soul physical activity program for African American women. Western J Nurs Res. 2011;33(5):652–670. doi: 10.1177/0193945910383706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilbur J, McDevitt JH, Wang E, et al. Outcomes of a home-based walking program for African-American women. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22(5):307–317. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.5.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pekmezi D, Marcus B, Meneses K, et al. Developing an intervention to address physical activity barriers for African-American women in the deep south (USA) Women’s Health (London, England) 2013;9(3):301–312. doi: 10.2217/whe.13.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joseph RP, Keller C, Adams MA, Ainsworth BE. Print versus a culturally-relevant Facebook and text message delivered intervention to promote physical activity in African American women: a randomized pilot trial. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15:30–30. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christie C, Watkins JA, Weerts S, Jackson HD, Brady C. Community church-based intervention reduces obesity indicators in African American females. Internet Journal of Nutrition & Wellness. 2010;9(2):8p. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karanja N, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, Kumanyika SK. Steps to soulful living (steps): a weight loss program for African-American women. Ethnicity & Disease. 2002;12(3):363–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams T, Burns D, Forehand JW, Spurlock A. A Community-Based Walking Program to Promote Physical Activity Among African American Women. Nursing for Women’s Health. 2015;19(1):26–35. doi: 10.1111/1751-486X.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adult participation in aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activities-United States, 2011. MMWR. 2013;62(17):326–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melnyk BM, Morrison-Beedy D. Intervention Research: Designing, Conducting, Analyzing, and Funding. New York, NY: Springer Publisher Company; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Versey HS. Centering Perspectives on Black Women, Hair Politics, and Physical Activity. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(5):810–815. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutes LD, Steinbaugh EK. Theoretical models for pedometer use in physical activity interventions. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2010;15(3):143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fitzgibbon M, Stolley M, Schiffer L, Sharp L, Singh V, Dyer A. Obesity Reduction Black Intervention Trial (ORBIT): 18 - month results. Obesity. 2010;18(12):2317–2325. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]