Abstract

This study examined the developmental profile of male infants with fragile X syndrome (FXS) and its divergence from typical development and development of infants at high risk for autism associated with familial recurrence (ASIBs). Participants included 174 boys ranging in age from 5 to 28 months. Cross-sectional profiles on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning indicated infants with FXS could be differentiated from typically developing infants and ASIBs by 6 months of age. Infants with FXS displayed a trend of lower developmental skills with increasing age that was unique from the typically developing and ASIB groups. Findings suggest infants with FXS present with more significant, pervasive and early emerging delays than previously reported with potentially etiologically distinct developmental profiles.

Keywords: fragile X syndrome, autism, early development, infants, Mullen

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common heritable condition associated with intellectual disabilities and autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Hagerman, Rivera, & Hagerman, 2008). Nearly all post-pubertal males with FXS have an intellectual disability (Bailey et al., 2008) and up to 50 – 75% of males with FXS meet diagnostic criteria for ASD (Kaufmann et al., 2004; Hall, Lightbody, & Reiss, 2008; Harris et al., 2008; Klusek, Martin, & Losh). Despite the high association of intellectual disabilities and ASD in FXS, few studies have examined the emergence of these co-occurring conditions in FXS, and no work has contrasted the developmental profiles of infants with FXS to those at established risk for ASD or developmental delays. In this paper, we examine broad indicators of early development in infants with FXS contrasted to typically developing infants and infants at high risk for adverse developmental outcomes given a family history of ASD. Our goal was to determine if specific profiles of early development could be identified across etiologically distinct groups of infants at elevated risk for ASD and developmental delays.

Prospective studies of developmental trajectories in infants later diagnosed with FXS, ASD or developmental delays are critical for a number of reasons. First, in the absence of a family history, the average age of diagnosis for both ASD and FXS is at 3 years of age despite symptoms present in the first year of life (Bailey, Raspa, Bishop, & Holiday, 2009; Matthews, Goldberg, & Lukowski, 2013). Thus, refined characterization of the infant phenotype in ASD and FXS has the potential to identify markers that could be useful for earlier and more specific diagnosis resulting in early treatment. Second, describing early developmental profiles of etiologically distinct groups of infants at high risk for ASD is important to address the latent heterogeneity present in ASD. Studies targeting cross-syndrome comparisons in ASD are notably lacking particularly work with young children and infants. This work can be highly informative to address commonalities and similarities across “the autisms”. Third, documenting early developmental profiles can identify behavioral or cognitive factors associated with vulnerability to later-emerging symptoms or secondary disorders (e.g., attention deficits, anxiety) both within and across etiology-specific groups. Fourth, cross-syndrome developmental studies can document individual differences or unanticipated age-related patterns of development that could affect treatment response (e.g., shift from hypo to hyper-arousal) that could be etiologically distinct.

Early Development in Fragile X Syndrome

Two longitudinal studies of broad development including toddlers or young children with FXS exist. In the first study, 46 boys with FXS between the ages of 24 and 72 months were followed every 6 months for an average of 2 years and a total of 185 assessments (Bailey, Hatton, & Skinner, 1998). As reflected on the Battelle Developmental Inventory (Newborg, Stock, Wnek, Guidubaldi, & Svinicki, 1984), boys with FXS made stable developmental gains; however, their rate of development was approximately half that expected for typically developing children. Boys with FXS were significantly delayed in Cognitive, Communication, Adaptive, Motor and Personal-Social domains at all ages, with Motor and Adaptive Behavior scores consistently higher than Communication and Cognitive scores. No comparison group, measures of autistic behavior or participants less than 2 years of age were included in this study.

A subsequent study included repeated assessments of 55 boys with FXS between the ages of 8 and 68 months of age using the MSEL with a mean of 3.4 assessments per child for a total of 189 assessments (Roberts et al., 2009). Results indicated that infants and young children with FXS made developmental gains over time, albeit at a rate about half that of typically developing children as shown in the initial study with older aged children (Bailey et al., 2008). A decline in the rate of development was not evident as had been reported elsewhere with older aged children with FXS (Lachiewicz, Gullion, Spiridigliozzi, & Aylsworth, 1987). Delays were initially evident by 9 months of age in the total score and in the Receptive and Expressive Language domains with delays in Visual Reception emerging at 10 months of age followed by delays in Fine Motor emerging at 13 months of age. Increased severity of autistic behavior, as measured by the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler et al., 1988), was strongly associated with more severe delays across all domains particularly in Communication and Fine Motor domains (Roberts et al., 2009).

Given the clear co-occurrence of ASD diagnoses and features in FXS, studies that examine early development and the emergence and stability of ASD features are important both for refining the phenotype of FXS and for contributing to the disassociation of these two syndromes. However, few studies have been published on the development of children with FXS less than 5 years of age and only a handful of recent studies have examined early emerging features of autism or cross-syndrome comparisons of early development in FXS. Initial work examining broad developmental indicators in young children with FXS compared to those with idiopathic ASD and those with both FXS and ASD, report mixed findings. Some work suggested that children (21 months of age and older) with FXS and comorbid ASD exhibited more significant delays, particularly in Fine and Gross Motor domains, than children with FXS alone and those with ASD alone (Bailey, Hatton, Mesibov, Ament, & Skinner, 2000). However, a different study found that young children with FXS and ASD were highly similar to those with idiopathic ASD and that young children with FXS without ASD resembled those with non-specific developmental delays (Rogers, Wehner, & Hagerman, 2001). More recent work focusing on infants and the emergence of autistic features in FXS suggests that visual attention is atypical in infants with FXS as young as 9 months of age and is associated with later emerging autistic behavior (Roberts, Hatton, Long, Anello, & Colombo, 2012) with arousal dysregulation implicated mechanistically (Roberts, Tonnsen, Robinson, & Shinkareva, 2012).

In summary, there are few studies of early development in FXS, and no studies exist that contrast broad development in infants with FXS to infants at risk for ASD. Existing work suggests that developmental delays emerge by 9 months of age and that development in these first 2 years of life is strongly negatively impacted by the severity of autistic behavior suggesting some similarities to early developmental patterns of infants with an older sibling diagnosed with ASD (ASIBs); however, syndrome specific differences have not been directly investigated during infancy.

Early Development in Autism

Given that the presence of an intellectual disability is one of the primary factors accounting for outcomes in children with ASD (Vivanti, Barbaro, Hudry, Dissanayake, & Prior, 2013) with 37% of preschool children with ASD meeting criteria for an intellectual disability (Rivard, Terroux, Mercier, & Parent-Boursier, 2015), efforts to document the early developmental profiles in young children at risk for ASD have accelerated. In fact, the emergence of empirically grounded diagnostic algorithms has been proposed based, in part, on developmental trajectories to predict the primary classifications of unaffected (~59%), social/communication delay or broader autism phenotype (11%) and ASD with and without co-morbid intellectual disability (~25%) (Landa, Gross, Stuart, & Bauman, 2012). Thus, studies that examine the developmental diversity within high risk groups without regard to diagnostic status are highly informative (Landa et al., 2012) with cross-syndrome comparisons as an important component of these efforts.

The bulk of recent work describing the early development of children with ASD has been prospective and longitudinal typically targeting ASIBs as a high risk group, given the increased recurrence rate of autism in approximately 20% of cases (Jones, Gliga, Bedford, Charman, & Johnson, 2014; Landa & Garrett-Mayer, 2006; Rice et al., 2007). The bulk of the prospective longitudinal work (Landa & Garrett-Meyer, 2006; Landa, Gross, Stuart & Fahery, 2013; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2005; see Jones et al., 2014 for a review) report a general absence of developmental markers at 6 months with features emerging between 12 −14 months in communication domains for ASIBs later diagnosed with ASD compared to typical controls and ASIBs who did not meet later diagnostic criteria for autism. Developmental profiles unique to diagnostic outcome have begun to emerge with evidence suggesting 4 distinct classes of high risk infants. Classes include a normative development group, a language/motor delay group, a developmental slowing group, and an accelerated development group (Landa et al., 2012). Unaffected ASIBs primarily fell in the accelerated and normative classes, and most ASIBs with the broader autism phenotype fell in the normative or language delay class. The majority of ASIBs later diagnosed with autism fell in the developmental slowing class. However, there was more variability in class placement for those diagnosed late who were distributed fairly equally across the normative, language/motor delay and developmental slowing classes in contrast to those identified early who primarily fell in the developmental slowing class.

Taken together, research on the early development of infants later diagnosed with autism reflects important age-related trajectories. Developmental skills appear generally intact through 6 months of age followed by a pattern of increasing divergence from non-ASD samples with divergence first observed at 12–14 months of age using broad developmental measures (Landa et al., 2006, 2013; Sacrey, Bryson, & Zwaigenbaum, 2013; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2005). As noted by Landa (2012), the atypical developmental trajectories of infants and toddlers later diagnosed with ASD represent a continuum of developmental disruption including developmental deceleration, plateauing, and regression.

Current Study

Identification of early developmental profiles in FXS and determination of their shared and unique features in contrast to samples at risk for autism and developmental delay is critical for informing developmental surveillance efforts not only for infants with FXS but also for those groups with features that overlap with those observed in FXS. In the absence of a family history, FXS is diagnosed years after initial symptoms emerge, potentially resulting in a delay of early intervention services which may exacerbate the severity of symptoms over time and increase the likelihood of secondary conditions emerging and uninformed family planning. However, to date, no published study has examined early development of FXS to infants at risk for developmental delay or ASD in the first year of life. Thus, the overarching aim of the current study is to identify the developmental profile in infants with FXS focusing on the age and domain in which delays emerge. Also, we contrast the FXS developmental profile to a typically developing sample and to a sample of ASIBs who are also at high risk for both developmental delays and ASD diagnoses. This cross-group comparison design will enable us to identify divergence from typical development and whether etiology specific developmental profiles can be identified across the high risk etiologically distinct groups. Three research questions guided this work.

Does divergence from typical development differ in infants with FXS contrasted to infant ASIBs?

Are developmental profiles in infants with FXS distinct from typically developing infants and infant ASIBs?

Can developmental profiles on broad developmental domains differentially predict group membership in infants with FXS contrasted to typically developing infants and infant ASIBs?

We hypothesized that group differences would be evident by 9 months of age with the FXS group showing greater delays than the ASIB and typically developing group. Additionally, we hypothesized that group membership for the infants with FXS would be accurately discriminated from the typically developing and ASIB groups with clearer distinctions apparent between the infants with FXS and those who are typically developing.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was not a single planned study, but rather an amalgamation of data from three sources. The first source was an ongoing longitudinal study on early indicators of ASD in high-risk populations (PI: Roberts; FXS, ASIBs, typically developing), the second was an extant database from a study examining family adaptation to FXS (PI: Bailey; FXS) and the third was the National Database for Autism Research (NDAR), a collective national database for autism research funded by the National Institutes of Health (FXS, ASIBs, typically developing). A more detailed description of the NDAR database, including all relevant child questionnaires, can be found at http://ndar.nih.gov/. Combining data across sources allowed us to examine development across a range of ages for all groups and to maximize our sample size; however, these procedures limited the measures we could include given the variability across sources. Based on the available data we have identified all males 2 years old (up to 28 months) and younger who were unambiguously characterized as falling into one of the three groups of interest and had a complete developmental assessment and basic descriptive data. Outcome data in terms of ASD status were not routinely available; thus, our sample represents infants at high risk for ASD rather than those of known ASD status. Also, our focus was on detection of etiological specific patterns of disrupted development in high risk groups regardless of outcome.

Participants

Data from a total of 174 infant boys ranging in age from 5 to 28 months (mean age = 15 months) were included in this study. Of the 174 infants, 63 had FXS, 36 were ASIBS, and 75 had no developmental concerns (typical controls). Data ascertainment for the FXS group was primarily through our two research studies (74%) with the rest drawn from the NDAR database. Of the typical group, 36% were recruited through the research studies with the rest sampled from NDAR. For the ASIB group, 69% were recruited through the two large scale studies and the rest drawn from NDAR. Children with FXS were diagnosed through genetic testing and all had the full mutation. Autism siblings were identified by having an older sibling with ASD diagnosed by a licensed clinician and documented in a written diagnostic report. Among the ASIBs drawn from our own studies (25:36), we ruled out FXS through a lack of family history or genetic report. For participants drawn from our studies, 45% of the FXS infants and 17% of the ASIBs were receiving early intervention primarily in the form of speech-language intervention and general developmental stimulation. These data are not available from other sources. Typical controls were infants with no family history of ASD or developmental delays, born full-term with no medical complications and with domain and composite scores within 1 standard deviation of the normative mean. In instances where there were multiple assessments for any given participant, we generally selected the earliest age for which complete data were available, given our interest in detecting the emergence of delays. All infants were administered the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL). Parents provided written consent. Participant ages are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Age by Group.

| Group | n | Mean age | Min age | Max age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical | 75 | 13.21 | 5 | 24 |

| FXS | 63 | 15.05 | 6 | 28 |

| ASIB | 36 | 14.05 | 8 | 24 |

Note: FXS = fragile X syndrome; ASIB = autism sibling

Measure

The MSEL (Mullen, 1995), a standardized measure of development for children birth to 69 months of age, was available for all participants. The MSEL was chosen because of its strong reliability and validity and high correlations (r = 0.70) with the Bayley’s Mental Development Index (Bayley, 1993). The MSEL consists of five subscales including gross motor (GM), visual reception (VR), fine motor (FM), receptive language (RL), and expressive language (EL) domains. T-scores are derived for each domain and an Early Learning Composite (ELC) score is derived as a summary of overall development. The Visual Reception, Fine motor, Receptive Communication and Expressive Communication scales contribute to the ELC, a norm-referenced, standardized score (M = 100, SD = 15). The gross motor subdomain was not included in the present study as these data were not available for all participants and are not included in the calculation of the ELC score. For the FXS sample, 11% had scores that met the floor on the ELC (standard score of 49) with the other groups not having participants at the floor. Participants with scores at the floor were not excluded from the analyses because they did show variability on subtest scores and accounted for a minority of our sample. Descriptive statistics on performance on the five Mullen Domains are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics (means and standard deviations) of Mullen T Scores for the Four Groups of Participants by Chronological Age Clusters.

| Mullen Subscales | TD (n = 75) [M (SD)] |

FXS (n = 63) [M (SD)] |

ASIB (n = 36) [M (SD)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months (5 – 7.4) | n= 9 | n = 5 | n = 0 |

| Early Learning Composite | 93.78 (6.85) | 85.80 (13.77) | - |

| Visual Reception | 52.22 (6.26) | 38.40 (11.63) | - |

| Fine Motor | 49.22 (8.94) | 48.00 (12.43) | - |

| Receptive Language | 42.11 (6.68) | 47.60 (7.09) | - |

| Expressive Language | 43.55 (5.92) | 35.80 (9.07) | - |

| 9 months (7.5 – 10.5) | n= 11 | n = 21 | n = 14 |

| Early Learning Composite | 98.27 (8.01) | 76.23 (8.50) | 97.64 (14.96) |

| Visual Reception | 47.91 (7.75) | 36.71 (7.44) | 49.48 (10.86) |

| Fine Motor | 48.54 (7.31) | 37.05 (12.17) | 54.64 (14.04) |

| Receptive Language | 49.54 (6.61) | 37.24 (6.58) | 43.28 (7.17) |

| Expressive Language | 49.09 (4.23) | 36.81 (8.36) | 46.64 (8.97) |

| 12 months (10.6 – 15.0) | n = 38 | n = 11 | n = 12 |

| Early Learning Composite | 100.34 (8.21) | 72.73 (16.34) | 105.58 (16.35) |

| Visual Reception | 52.68 (7.39) | 35.45 (10.50) | 57.08 (11.67) |

| Fine Motor | 53.76 (6.67) | 36.64 (10.39) | 58.75 (8.53) |

| Receptive Language | 44.74 (6.64) | 36.00 (10.31) | 46.33 (6.77) |

| Expressive Language | 48.42 (6.74) | 34.36 (10.57) | 48.00 (13.32) |

| 18 months (15.1 – 21.0) | n = 10 | n = 8 | n = 2 |

| Early Learning Composite | 98.00 (8.19) | 58.00 (11.16) | 103.00 (1.41) |

| Visual Reception | 48.8 (7.64) | 28.50 (10.18) | 50.00 (9.90) |

| Fine Motor | 51.50 (5.62) | 30.00 (12.15) | 52.20 (0.71) |

| Receptive Language | 46.00 (7.74) | 22.25 (3.10) | 50.00 (4.24) |

| Expressive Language | 46.80 (7.08) | 23.75 (7.90) | 53.00 (4.24) |

| 24 months (21.1 – 25.0) | n = 7 | n = 18 | n = 8 |

| Early Learning Composite | 98.28 (7.29) | 58.06 (10.97) | 89.87 (21.51) |

| Visual Reception | 50.28 (3.82) | 26.67 (8.51) | 46.87 (12.77) |

| Fine Motor | 47.86 (4.70) | 22.83 (4.98) | 45.87 (8.36) |

| Receptive Language | 49.86 (8.93) | 26.22 (8.74) | 42.87 (16.97) |

| Expressive Language | 46.86 (6.17) | 26.72 (8.02) | 42.00 (18.87) |

TD = typically developing; FXS = fragile X syndrome; ASIB = autism sibling.

Procedures

Assessments for the FXS, typical and ASIB groups recruited through the two large-scale studies were conducted in the participants’ homes by two researchers, with the primary examiner administering the MSEL during the first day of the two-day assessment with completion of the Mullen on the second day as needed (e.g., child fussiness, inattention). Protocols were scored using the computerized scoring software and checked for reliability by trained research assistants. All families gave informed consent before participation.

Analyses

Statistical analyses were generated using SAS software, version 9.3 of the SAS system for windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. First, linear regression models were conducted to investigate the divergence from the typical reference group for the two clinical groups: FXS and ASIBs. Differences were examined in the Early Learning Composite (ELC) of the MSEL followed by separate examination on the four domains of the MSEL: VR, FM, RL, and EL. Clinical group (FXS, ASIB, or TD), child chronological age and an age by clinical group interaction were included in each regression model. Within each model, to probe the interaction, regions of significance were estimated using Johnson-Neyman techniques (Johnson and Fay, 1950; Hayes and Matthews, 2009) to determine the ages at which MSEL scores diverged from the typical group in our two at risk samples. Results were considered significant at alpha level of .05.

Second, linear regression models were used to contrast the developmental profiles of infants with FXS to ASIBs at a composite and domain level. Third, discriminant analyses were conducted to predict group membership for the FXS group contrasted to ASIBs from the four Mullen subdomains. Discriminant function analyses are adversely affected by unequal group sizes; thus, we constrained our groups to equal sizes using the sample with the smallest size as the target. If more than one participant matched in age, we randomly selected from the eligible participants. This resulted in 34 ASIBs and 36 TD matched to an equal number of FXS for each analysis. The assumption of equality of the variance-covariance matrices for the groups was not violated, and a linear classification procedure with leave-one-person-out cross validation was used.

Results

Divergence from Typical Development in FXS contrasted to ASIBs

The first set of analyses contrast the divergence from typical development in infants with FXS and infant ASIBs using both composite and domains of broad development.

Early Learning Composite

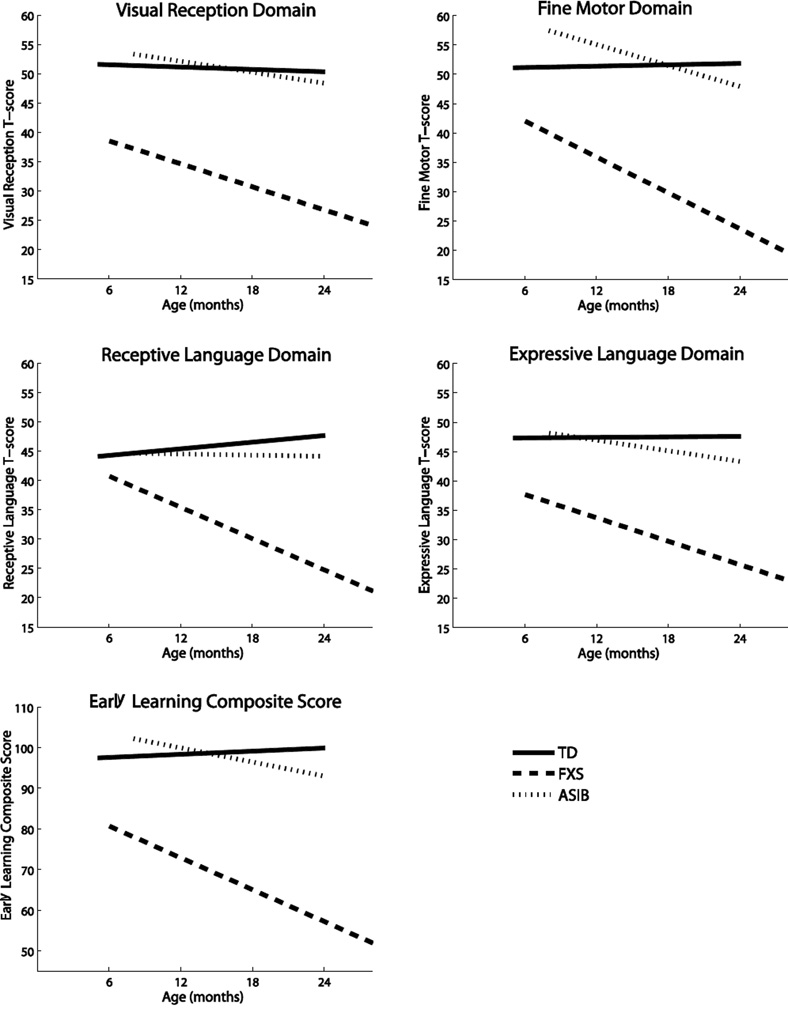

Regression analyses for the ELC revealed a significant difference by group, F (5, 168) = 60.37, p = <.0001, with an age by group interaction (p =.0002). ELC scores for the FXS group (B = −1.43, p <.0001) declined across age with delays evident by 6 months of age. The ASIB group was not different from the typical group (p = .10) across age.

Visual Reception

Regression analyses for the VR Domain revealed a significant difference by group, F (5, 168) = 38.82, p = <.0001. VR scores for the FXS group (B = −0.59, p =0.03) declined across age with delays evident by 6 months of age. The ASIB group showed no difference from the typical reference group (p =.46) across age. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Linear Regression Models for the Four Domain Scores

Fine Motor

Regression analyses for the FM Domain revealed a significant difference by group, F (5, 168) = 44.90, p < .0001, with an age by group interaction (p = .0007). Scores from the FXS group declined with age (B = −1.06, p =.0001) and delays evident by 6 months of age. The ASIBs showed no age effect (p =.06).

Receptive Language

Regression analyses for the RL domain revealed a significant difference by group, F (5, 168) = 26.17, p < .0001 with an age by group interaction (p < .0001). The FXS group (B = −1.08, p < .0001) showed a decline with age. The ASIB group showed no difference from the TD group across age (p =.48). Estimated regions of significance indicated that the FXS group diverged from the typical reference group at 6.63 months of age.

Expressive Language

Regression analyses for the EL domain revealed a significant difference by group, F (5, 168) = 27.99, p < .0001 with an age by group interaction (p = .03). The FXS (B = −.68, p = .01) showed a decline with age with delays evident by 6 months of age. The ASIBs showed no difference from the TD group across age (p = .33).

FXS Divergence from ASIBs

To focus on the distinctness of the FXS developmental profile from infants at risk for ASD, we contrasted composite and domain developmental scores of the FXS group to this group.

Early Learning Composite

For the ASIB comparison, analyses for the ELC revealed a difference by group, F (3,93) = 41.07, p = < .0001 and no age by group interaction (p = .17) with the FXS group lower across age emerging at 6 months of age.

Visual Reception

For the ASIB comparison, analyses for the VR Domain revealed a significant difference by group, F (3,93) = 30.19, p = < .0001 with no age by group interaction (p = .28) with the FXS group lower across age present by 6 months of age.

Fine Motor

For the ASIB comparison, analyses for the FM Domain revealed a difference by group, F (3,93) = 37.78, p < .0001 with no age by group interaction (p = .35) with the FXS group lower across age starting at 6 months of age.

Receptive Language

For the ASIB comparison, analyses for the RL domain revealed a group difference, F (3,93) = 21.33, p < .0001 with an age by group interaction (p = .02). The FXS group (B = −.97, p = .0002) showed a decline with age. The ASIB group showed no difference from the TD group across age (p = .39). The lower scores in the FXS group emerged at 6 months of age.

Expressive Language

For the ASIB comparison, analyses for the EL domain revealed a significant difference by group, F (3,93) = 18.87, p < .0001 with no age by group interaction (p = .32). The FXS group had lower scores that emerged by 6 months of age.

Predicting Group Membership for the FXS contrasted to TD and ASIBs

To investigate whether FXS group membership could be predicted contrasted to the TD, and ASIB groups using the four MSEL domains (VR, FM, RL, EL), we conducted discriminant function analyses selecting subgroups matched on age and sample size.

FXS and TD

Significant mean differences (p < .001) between the FXS and TD groups were observed across all domains with the overall test of relationship between the group membership and MSEL domains significant (F (4, 67) = 26.70, p < .0001). The structure loadings, consisting of the correlations between predictors and the discriminant function, indicated that all domains contributed to group membership. Expressive language (.85) and Visual Reception (.83) were the strongest followed by Fine Motor (.74), and Expressive Language (.70). Scores were significantly lower for the FXS group on all domains. Accurate prediction of group membership was moderate to high with 94% (34/36) of boys with FXS classified correctly and 75% (27/36) of the TD group classified correctly with an overall cross-validated classification rate of 85%.

FXS and ASIB

Significant mean differences (p < .001) between the FXS and ASIB groups were observed for all four predictor variables with the overall test of relationship between the group membership and MSEL domains significant (F (4, 64) = 13.09, p < .0001). The structure loadings, consisting of the correlations between predictors and the discriminant function, indicated that all domains contributed to group separation. Visual Reception (.90) and Fine Motor (.87) were the best predictors for distinguishing between the two groups followed by Expressive Language (.73) and Receptive Language (.56). Scores were lower for the FXS group than the ASIB group across domains. Accurate prediction of group membership was moderate with 68% (23/34) of boys with FXS classified correctly and 80% (28/34) of the ASIBs classified correctly with an overall cross-validated classification rate of 74% (Table 4).

Table 4.

Classification Results Showing Frequency and Percentage of Participants Classified Correctly from Analysis, Cross-Validated.

| Predicted Group Membership | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FXS | ASIB | |||

| Actual Group Membership | n | % | n | % |

| FXS (n = 28) | 21 | 75.00 | 7 | 25.00 |

| ASIB (n = 28) | 4 | 14.29 | 24 | 85.71 |

Note: FXS = fragile X syndrome; ASIB = autism sibling.

Discussion

This study examined the developmental profile of male infants with FXS and its divergence from typical development and contrasted the specificity of the FXS developmental profile to infants at high risk for idiopathic ASD to determine if disassociations could be made across two etiologically-distinct samples at high risk for ASD. This work is important given that the diagnosis of both ASD and developmental delay are based on clinical presentation with clusters of symptoms that overlap (Mitchell, Cardy, & Zwiagenbaum, 2011). Developmental profiles were determined using cross-sectional profiles of broad development at a composite and domain level on the MSEL with domain scores also used to predict group membership. Our findings suggest that infants with FXS display significant and pervasive developmental delays that emerge early within the first year of life with a developmental profile that is distinct from those at risk for ASD due to a family history of ASD. Of note, we report that delays were evident by 6 months of age with a significant decrease in the rate of development over the first 2 years in infants with FXS that was not observed in the other groups.

FXS Divergence from Typical Development

The developmental profile of infants with FXS deviated from the typical group at a composite and domain level across age with initial emergence at 6 months of age. The developmental profile for the infants with FXS diverged from the typical group in a manner distinct from the ASIB group. ASIBs displayed generally intact development with no divergence from the typically developing group across age. The divergence of FXS from typical development at an early age was anticipated and generally consistent with our previous work which focused on development across the broad age range of 1 to 5 years of age (Roberts et al., 2009). However, findings of our current study focused on development in the first 2 years indicating that divergence from typical development is present by 6 months of age with an increase in divergence from typical development with age. Our previous work identified that developmental delays emerged at 9 months of age and only on the composite and communication domains (Roberts et al., 2009). In contrast, our current study suggests delays in the composite and across all domains of development (Fine Motor, Visual Reception, Expressive Communication, and Receptive Communication) by 6 months of age. Study discrepancies likely exist due to our focus on infancy with inclusion of a larger sample of infants 9 months of age and younger which enables the detection of delays at an earlier age. Of note, the youngest age of the infants with FXS in our current study is 6 months of age so it is quite possible that delays are present and detectable in infants with FXS younger than 6 months of age; however, that is beyond the scope of the current study and an aim for future work. Also, given that the majority (87%) of the infants with FXS were identified based on a family history of FXS, it is likely that the developmental profiles characterized in this paper may represent a milder set of delays than infant who are identified through routine surveillance.

Our report of delays present at 6 months of age and decrease in developmental standard scores in the first two years of life is novel and somewhat unexpected as a number of studies imply that delays do not emerge until the end of the first or the middle of the second year of life in infants with FXS. In fact, initial reports of early development in FXS suggested that infants with FXS may display intact developmental skills with delays not emerging until the preschool years (Freund, Peebles, Aylward, & Reiss, 1995; Hagerman et al., 1994). While a decline in developmental scores for children 2 to 6 years of age (Bailey et al., 1998) and a reduced rate of development reported in our previous work including infants and toddlers 8–48 months of age (Roberts et al., 2009) has been reported, the present study is the first to document broad developmental delays are present very early in infancy at an age younger than ever reported. This suggests that the first two years of development in FXS may represent a sensitive period likely reflecting rapid brain maturation and organization as has been reported in atypical trajectories of brain volume in FXS (Hazlett, Poe et al., 2012) and other neurodevelopmental disorders including ASIBs (Shenn et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 2012).

In summary, the FXS group displayed significant, pervasive and early emerging delays that are clearly distinct from typical controls. The high degree of accuracy with which the infants with FXS were discriminated from the infants with typical development (85%) suggests that developmental screening and surveillance methods routinely used in community settings should be sensitive to detect developmental delays in infants with FXS within the first year of life. This is supported by evidence from pilot studies indicating that ≥ 90% of 9 and 12 month old infants with FXS (n=13) failed routine developmental screenings (Mirrett, Bailey, Roberts, & Hatton, 2004). While all domains of development appear delayed and contribute to discrimination from typical controls, Expressive Language and Visual Reception emerged as the strongest domains to discriminate infants with FXS from typical controls.

FXS Divergence from ASIBs

Distinct developmental profiles were evident by 6 months of age in infants with FXS contrasted to ASIBs at both a composite and domain level. In fact, the groups were distinct for every MSEL score with the FXS group consistently displaying lower developmental skills across age. In predicting group membership from the MSEL domains, the ASIB group was accurately categorized at a moderately high rate of accuracy (80%) with the FXS group as moderate (68%). While all domains contributed to the cross-group categorization, the Fine Motor and Visual Reception domains most strongly contributed to the group distinctions with lower scores in these two domains strongly representing infants with FXS than ASIBs. Discrimination of FXS appears most accurate contrasted to the typical controls (85%) with a lower rate when contrasted to the ASIBs (74%) which we attribute to the greater variability in developmental profiles for the ASIBs.

The lower Fine Motor skills in the FXS group as one of the strongest discriminant factors in differentiating the groups is interesting in light of evidence that early emerging motor delays have been associated with increased likelihood of meeting criteria for ASD (Landa et al., 2013) and with communication delays in ASIBs (Bhat, Galloway, & Landa, 2012). In our work, we found that motor items on the Autism Observation Schedule for Infants (AOSI; Bryson et al., 2008) discriminated ASD features in infants with FXS (Roberts et al., under review). Indeed, motor abnormalities have been described as a putative endophenotype for ASD potentially pointing to mechanistic factors as both motor and social-communication deficits have been indirectly associated with the same physiological systems (Esposito & Pasca, 2013). And, existing studies support a relationship between fine motor delays and increased features of autism in young children with FXS (Roberts et al., 2009; Zingerivich et al., 2009) and infants (Roberts et al., under review).

Beyond standardized broad-based motor measures such as the MSEL, we have also found an association between motor abnormalities reflected in atypical eye movement (i.e., attention disengagement) and elevated ASD symptoms in infants with FXS (Roberts, Hatton et al., 2012). These atypical eye movements have been associated with reduced heart rate variability independent of mental age (Roberts, Hatton et al., 2012), and are consistent with reports of elevated physiological arousal during infancy predicting later emerging ASD symptoms in FXS (Roberts, Tonnsen et al., 2012). Thus, our finding that increased motor deficits in the infants with FXS contributes strongly to group disassociation from the ASIB group may reflect the higher risk for ASD in the FXS group (~60%) versus that in the undiagnosed ASIBs (~20%). However, motor delays may also reflect general developmental delays rather than represent a specific marker of ASD risk. Confirmation of the early emergence of fine motor delays in our current study and the accumulated evidence of an association of motor delays and ASD symptomology in FXS and idiopathic ASD highlight the importance of assessing motor skill development and its association with ASD in FXS.

In summary, we report distinct developmental profiles that differentiate infants with FXS from ASIBs despite both groups having elevated risk for ASD and developmental delay; albeit, the FXS group has higher risk for both outcomes. In studies of the developmental profile of ASIBs who are later diagnosed with ASD, their profile is typically characterized by developmental slowing that become progressively more severe over time with delays emerging around 12 – 14 months of age (Landa et al., 2012). However, a fair degree of variability exists with an outcome diagnosis of ASD also associated with normative development and delays only in receptive language and motor domains (Landa et al., 2012). Thus, the developmental profiles of infants with FXS in our study partially mirror those of infants with an outcome diagnosis of ASD, although we did not examine these effects longitudinally. And, the delays are apparent much earlier in FXS (i.e., at 6 months versus 12–14 months of age).

Limitations

Although this study represents the largest and youngest sample of infants with FXS examining broad indicators of development and is the only one to contrast ASIBs to FXS, there are a number of limitations and cautions. The use of cross-sectional data, rather than longitudinal, is a limitation. Additionally, we did not account for later diagnostic outcomes of ASD in any group and, instead, focused on ASD “at risk” status regardless of outcome which, while that was our intent, imposes limitations in the interpretation of our findings. Thus, we cannot describe developmental trajectories based on ASD diagnostic determination, only by ASD risk status. Also, although we included only ASIBs who did not indicate a family history of FXS, we did not require genetic testing to confirm the absence of FMR1 mutations. Finally, our sample sizes are small for the youngest age group.

Implications and Future Directions

Fragile X syndrome is the leading known heritable cause of intellectual disabilities and ASD. As such, cross-syndrome studies contrasting early developmental profiles in infants with FXS to non-FXS infants also at risk for these compromised outcomes can contribute to phenotypic refinement and potential early identification and treatment. This study contributes to the refinement of the infant phenotype not only in FXS but also to ASD which is highly heterogeneous. Given the high prevalence of ASD, early differentiation of ASD from other disorders is critical to facilitate diagnosis and treatment as evidence suggests that interventions that are autism-specific are most efficacious for this group (Dawson et al., 2010). However, few studies have examined heterogeneity across identifiable high risk cohorts in the first 24 months of life, and none have contrasted broad developmental markers in idiopathic autism to FXS, the most common known genetic cause of ASD (Mitchell, Cardy, & Zwaigenbaum, 2011).

Given the known benefits of early intervention to both children and families, it is essential to develop effective strategies to identify early and differentially diagnose children with developmental delay. Etiological determination is a primary goal in the early diagnosis of developmental delay given potential differential treatment considerations. For example, genetic counseling for families with a child with ASD associated with FXS would include information based on a well-characterized familial transmission pattern unlike that for idiopathic autism which reflects a more generalized approach based on recurrence risk with few unambiguous risk factors. Likewise, treatment for a child with ASD associated with FXS might take into consideration co-morbidities such as intellectual disabilities and physiological hyperarousal which are more prominent in FXS than idiopathic autism.

In summary, we report developmental profiles in infants FXS that are distinct from typically developing infants and infants at high risk for ASD. Our findings suggest that etiologically distinct profiles of early development are present in the first year of development with 6 – 12 months implied as a sensitive period for developmental divergence not only from typical development but also within and across these syndromes. Of note, we report these findings using the MSEL, a standardized broad measure of development. Thus, we believe our findings may have practical implications given that the MSEL is more widely available and routinely used than most experimental methods which facilitates the application of our findings to practice. Future research is necessary to replicate and expand these findings including longitudinal studies, expansion of measures to more discrete indicators of development (e.g., visual attention, social-communication), inclusion of ASD outcomes, incorporation of biomarkers, and cross-syndrome comparisons of treatment efficacy.

Table 3.

Model Outcomes by Domain.

| Model 1 ELC Score |

Model 2 VR Domain |

Model 3 FM Domain |

Model 4 RL Domain |

Model 5 EL Domain |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variables | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Intercept | 98.85** | 1.37 | 51.13** | 1.04 | 51.63** | 1.08 | 45.93** | 0.97 | 47.59** | 1.04 |

| FXS | −28.50** | 2.02 | −17.76** | 1.54 | −17.72** | 1.59 | −12.25** | 1.43 | −15.16** | 1.54 |

| ASIB | 0.01 | 2.38 | 0.45 | 1.81 | 2.31 | 1.88 | −1.35 | 1.68 | −1.17 | 1.81 |

| Age | 0.13 | 0.28 | −0.07 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.21 |

| FXS x Age | −1.43** | 0.35 | −0.59* | 0.26 | −1.06** | 0.27 | −1.08** | 0.24 | −0.68* | 0.26 |

| ASIB x Age | −0.71 | 0.43 | −0.24 | 0.33 | −0.64 | 0.34 | −0.22 | 0.31 | −0.32 | 0.33 |

|

F (df) |

60.37** (5, 168) |

38.82** (5, 168) |

44.90** (5, 168) |

26.17** (5, 168) |

27.99** (5, 168) |

|||||

| R2 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.45 | |||||

Note: FXS = fragile X syndrome; ASIB = autism sibling; ELC = early learning composite; VR = visual reception; FM = fine motor; RL = receptive language; EL = expressive language.

p = <.05;

p = <.001

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by funding from the Office of Special Education Programs, US Department of Education; H324C990042 (PI: Bailey) and the National Institute of Mental Health; R01MH0901194-01A1 (PI: Roberts). Data and research tools used in the preparation of this article reside in and were analyzed using the NIH-supported NIMH Data Repositories, a collaborative informatics system created by the National Institutes of Health to provide a national resource to support and accelerate research in mental health related conditions.

References

- Bailey DB, Jr, Hatton DD, Mesibov G, Ament N, Skinner M. Early development, temperament, and functional impairment in autism and fragile X syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:557–567. doi: 10.1023/a:1005412111706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Jr, Hatton DD, Skinner M. Early developmental trajectories of males with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1998;103(1):29–39. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1998)103<0029:EDTOMW>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Jr, Raspa M, Bishop E, Holiday D. No change in the age of diagnosis for FXS: Findings from a national parent survey. Pediatrics. 2009;142 doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Raspa M, Olmsted M, Holiday DB. Co-occurring conditions associated with FMR1 gene variations: Findings from a national parent survey. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2008;146(16):2060–2069. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant development: Manual. Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat AN, Galloway JC, Landa RJ. Relation between early motor delay and later communication delay in infants at risk for autism. Infant Behavioral Development. 2012;35(4):838–846. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson S, Zwaigenbaum L, McDermott C, Romboug V, Brian J. The Autism Observation Scale for Infants: scale development and reliability data. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(4):731–738. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0440-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, Varley J. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e17–e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Pasca SP. Motor abnormalities as a putative endophenotype for autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2013;7:43. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund LS, Peebles CD, Aylward E, Reiss AL. Preliminary report on cognitive and adaptive behaviors of preschool-aged males with fragile X. Developmental Brain Dysfunction. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Hull CE, Safanda JF, Carpenter I, Staley LW, O’Connor RA, Taylor AK. High functioning fragile X males: demonstration of an unmethylated fully expanded FMR-1 mutation associated with protein expression. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1994;51(4):298–308. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320510404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Rivera SM, Hagerman PJ. The fragile X family of disorders: A model for autism and targeted treatments. Current Pediatric Reviews. 2008;4:40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hall SS, Lightbody AA, Reiss AL. Compulsive, self-injurious, and autistic behavior in children and adolescents with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113(1):44–53. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[44:CSAABI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SW, Hessl D, Goodlin-Jones B, Ferranti J, Bacalman S, Barbato I, et al. Autism profiles of males with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113(6):427–438. doi: 10.1352/2008.113:427-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett HC, Poe MD, Lightbody AA, Styner M, MacFall JR, Reiss AL, Piven J. Trajectories of early brain volume development in fragile X syndrome and autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(9):921–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Fay LC. The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika. 1950;15(4):349–367. doi: 10.1007/BF02288864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EJ, Gliga T, Bedford R, Charman T, Johnson MH. Developmental pathways to autism: A review of prospective studies of infants at risk. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2014;39:1–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Cortell R, Kau A, Bukelis I, Tierney E, Gray R, et al. Autism spectrum disorder in fragile X syndrome: Communication, social interaction, and specific behaviors. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2004;129A:225–234. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klusek J, Martin G, Losh M. Consistency between research and clinical diagnoses of autism in boys and girls with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2014;58(10):940–952. doi: 10.1111/jir.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachiewicz AM, Gullion CM, Spiridigliozzi GA, Aylsworth AS. Declining IQs of young males with the fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1987;92(3):272–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa R, Garrett-Mayer E. Development in infants with autism spectrum disorders: a prospective study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(6):629–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa R, Gross AL, Stuart EA, Bauman M. Latent class analysis of early developmental trajectory in baby siblings of children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(9):986–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa R, Gross AL, Stuart EA, Faherty A. Developmental trajectories in children with and without autism spectrum disorders: The first 3 years. Child Development. 2013;84(2):429–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews NL, Goldberg WA, Lukowski AF. Theory of mind in children with autism spectrum disorder: do siblings matter? Autism Research. 2013;6(5):443–453. doi: 10.1002/aur.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirrett PL, Bailey DB, Jr, Roberts JE, Hatton DD. Developmental screening and detection of developmental delays in infants and toddlers with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25(1):21–27. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S, Cardy JO, Zwaigenbaum L. Differentiating autism spectrum disorder from other developmental delays in the first two years of life. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2011;17(2):130–140. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen E. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Newborg J, Stock JR, Wnek L, Guidubaldi J, Svinicki J. The Battelle Developmental Inventory. Allen, TX: DLM/Teaching Resources; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rice CE, Baio J, Van Naarden BK, Doernberg N, Meaney FJ, Kirby RS. A public health collaboration for the surveillance of autism spectrum disorders. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2007;21(2):179–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivard M, Terroux A, Mercier C, Parent-Boursier C. Indicators of intellectual disabilities in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2015;45(1):127–137. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Hatton DD, Long ACJ, Anello V, Colombo J. Visual attention and autistic behavior in infants with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1316-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Tonnsen BL, McCary LM, Caravella BS, Shinkareva SV. Autism symptoms in infants with fragile X syndrome. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2903-5. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Tonnsen BL, Robinson A, Shinkareva SV. Heart activity and autistic behaviour in infants and toddlers with fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117(2):90–102. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Mankowski JB, Sideris J, Goldman BD, Hatton DD, Mirrett PL, et al. Trajectories and predictors of the development of very young boys with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009:1–10. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S, Wehner E, Hagerman R. The behavioral phenotype in fragile X: Symptoms of autism in very young children with FXS, idiopathic autism, and other developmental disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22:409–417. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacrey LA, Bryson SE, Zwaigenbaum L. Prospective examination of visual attention during play in infants at high-risk for autism spectrum disorder: A longitudinal study from 6–36 months of age. Behavioral Brain Research. 2013;256:441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E, Reichler RJ, Renner BR. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shen MD, Nordahl CW, Young GS, Wootton-Gorges SL, Lee A, Liston SE, et al. Early brain enlargement and elevated extra-axial fluid in infants who develop autism spectrum disorder. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 9):2825–2835. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanti G, Barbaro J, Hudry K, Dissanayake C, Prior M. Intellectual development in autism spectrum disorders: new insights from longitudinal studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JJ, Gu H, Gerig G, Elison JT, Styner M, Gouttard S, et al. Differences in white matter fiber tract development present from 6 to 24 months in infants with autism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(6):589–600. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11091447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingerevich C, Greiss-Hess L, Lemons-Chitwood K, Harris SW, Hessl D, Cook K, et al. Motor abilities of children diagnosed with fragile X syndrome with and without autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2009;53(1):11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bryson S, Rogers T, Roberts W, Brian J, Szatmari P. Behavioral manifestations of autism in the first year of life. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;23:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]