Abstract

Neurons communicate and transmit information predominantly through spikes. Given that experimentally observed neural spike trains in a variety of brain areas can be highly correlated, it is important to investigate how neurons process correlated inputs. Most previous work in this area studied the problem of correlation transfer analytically by making significant simplifications on neural dynamics. Temporal correlation between inputs that arises from synaptic filtering, for instance, is often ignored when assuming that an input spike can at most generate one output spike. Through numerical simulations of a pair of leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons receiving correlated inputs, we demonstrate that neurons in the presence of synaptic filtering by slow synapses exhibit strong output correlations. We then show that burst firing plays a central role in enhancing output correlations, which can explain the above-mentioned observation because synaptic filtering induces bursting. The observed changes of correlations are mostly on a long time scale. Our results suggest that other features affecting the prevalence of neural burst firing in biological neurons, e.g., adaptive spiking mechanisms, may play an important role in modulating the overall level of correlations in neural networks.

Keywords: burst, correlation, synaptic filtering, leaky integrate-and-fire, adaptation

Introduction

Many in vivo studies have revealed that neurons in a variety of brain areas frequently exhibit correlated activity (Zohary et al., 1994; König and Engel, 1995; Bair et al., 2001; Kohn and Smith, 2005; Okun and Lampl, 2008; Gerkin et al., 2013). However, the functions and consequences of correlations, and whether correlated input may carry any information have long been debated (Shadlen and Newsome, 1998; Panzeri et al., 1999; Salinas et al., 2001; Averbeck et al., 2006; Wolfe et al., 2010; Dipoppa and Gutkin, 2013). One of the key questions is how input correlations are processed and transmitted from a layer of neurons to the next (Shadlen and Newsome, 1998; Diesmann et al., 1999; Salinas and Sejnowski, 2000; Reyes, 2003; de la Rocha et al., 2007; Ostojic et al., 2009; Litwin-Kumar et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2012; Schultze-Kraft et al., 2013).

The conductance based LIF model (Stein, 1967) is often used in numerical and analytical studies of neural dynamics. However, it is very challenging to analytically derive the higher order statistics of output spike trains in this model, due to nonlinearity in the model and the resulting neural computations. Most previous work has studied the problem of correlation transfer by resorting to further approximations of single neuron dynamics and considering the pairwise correlation between two neurons receiving correlated inputs. A typical strategy is to use the diffusion approximation, mimicking the synaptic inputs by currents with Gaussian white noise (de la Rocha et al., 2007; Ostojic et al., 2009; Litwin-Kumar et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2012; Schultze-Kraft et al., 2013). This approach assumes that autocorrelations in the inputs are small. However, biological neurons may have slow synapses, in which ion channels take a substantial time to close after opening. This results in synaptic filtering and introduces autocorrelations in the inputs, rendering the assumption of small autocorrelations invalid.

In order to understand how input features, e.g., the level of background activity or input synchrony, affect correlation transfer, Ostojic et al. (2009) and Schultze-Kraft et al. (2013) studied changes of the membrane potential distribution of a neuron, and hence its probability of firing, in response to an additional input spike; Rosenbaum and Josić (2011) studied the conditional probability of a neuron to fire given that the other neuron has just recently fired. These approaches make the assumption that an input spike can contribute to at most one output spike, which is also problematic when neurons with slow synapses are considered, as synaptic filtering by slow synapses may induce burst firing (Moreno-Bote and Parga, 2004). The effects of synaptic filtering, and in particular the resulting burst firing, on neural correlation transfer is little known.

In this work, we aimed to study the role of synaptic filtering in correlation transfer by numerical simulations of a pair of LIF neurons receiving partially overlapping inputs. We found that neurons with slow synapses exhibit unexpectedly strong output correlations of a long time scale and at the same time fire in a strong bursting pattern. When controlling the amount of burst firing by incorporating biologically realistic spike adaptation mechanisms, namely after-spike hyperpolarizing currents (AHP) (Storm, 1987, 1990) and/or variable firing thresholds (Henze and Buzsáki, 2001; Platkiewicz and Brette, 2010), we observed that burst firing greatly enhances output correlations of a long time scale. But it only modestly increases output correlations at a shorter time scale, which correspond to synchrony. In the remainder of the work, we will refer to correlations at long time scales as “correlations” and correlations at short time scales simply as “synchrony,” unless otherwise specified. Furthermore, the “slowness” of synapses is always understood to be in comparison to the time scale of membrane potential integration.

Methods

Neuron model

Neural dynamics are simulated using the conductance-based LIF model (Stein, 1967). The dynamics of membrane potential are given by:

| (1) |

where C is the membrane capacitance, V(t) is the membrane potential, Vl, Ve and Vi are the membrane resting potential, reversal potential of excitatory synapses and that of inhibitory synapses, respectively. Gl is the membrane leak conductance. Ifahp and Isahp are fast and slow after-spike hyperpolarizing currents (See Section Membrane Potential Reset and After-Spike Hyperpolarization). When the membrane potential reaches the firing threshold Vth, the neuron fires a spike, and then the membrane potential is reset to the potential Vreset and clamped to that value for a fixed refractory period trefract.

Inputs are modeled by conductances. The excitatory and inhibitory synaptic conductances, denoted by Ge(t) and Gi(t) respectively, are modeled by linear summation of conductance changes induced by each presynaptic incoming spike.

To facilitate the interpretation of the neuron dynamics, we can separate the synaptic conductance into tonic parts and fluctuating parts (Richardson and Gerstner, 2005) and rewrite equation (1) (excluding the AHP currents) to

| (2) |

where Gtotal = Gl + 〈Ge(t)〉+〈Gi(t)〉 with 〈·〉 denoting the average over a long period of time, τeff = C∕Gtotal, V0 = [VlGl + Ve 〈 Ge(t)〉+Vi 〈 Gi(t)〉]∕Gtotal and Gsf(t) = Gs(t) − 〈Gs(t)〉, where the subscript s can be chosen as e, referring to “excitatory” or i, referring to “inhibitory.”

τeff in Equation (2) denotes the effective membrane time constant, which quantifies how fast the membrane responds to the fluctuating conductances and is related to the total synaptic conductance which depends on the level of average input activities. V0 refers to the mean membrane potential when spiking dynamics are ignored (Kuhn et al., 2004). The simulations reported below were run using equation (1), but we will refer to equation (2) and in particular the value of τeff in the interpretation of the results.

Spiking mechanism

In this work, the prevalence of neural burst firing is varied using different spiking mechanisms.

Firing threshold

In Sections Asymmetric Effects of Membrane Potential and Synaptic Integration Time Constants on Output Correlations and Slow Synaptic Filtering Induces Strong Burst Firing, a hard firing threshold is applied, which means the firing threshold is fixed at a constant value Vthrest.

In Section Burst Firing Greatly Enhances Output Correlations, a soft firing threshold is applied. The firing threshold is raised to Vthmax right after firing or at the end of the hard refractory period, if it is incorporated. The firing threshold Vth then decays exponentially to a rest value Vthrest as described in Clopath et al. (2010):

| (3) |

where τth is the threshold decay time constant.

When the soft firing threshold is applied, neurons need to depolarize more in order to fire successive spikes within a short period. Thus, it can be expected that the adaptive threshold can suppress burst firing that otherwise would occur.

Membrane potential reset and after-spike hyperpolarization

In Sections Asymmetric Effects of Membrane Potential and Synaptic Integration Time Constants on Output Correlations and Slow Synaptic Filtering Induces Strong Burst Firing, the membrane potential is brought to a reset potential Vreset right after firing and clamped to that value for a fixed refractory period trefract. In such cases Ifahp = Isahp = 0 at all time.

In Section Burst Firing Greatly Enhances Output Correlations, a more realistic reset mechanism is incorporated. The membrane potential is raised to Vspike right after crossing the firing threshold, mimicking the run-away rise of membrane potential in Hodgkin-Huxley neurons during a spike. Then, after a time delay tdelay, Ifahp and Isahp are set to Ifahpmax and Isahpmax respectively, mimicking the onset of two different after-spike hyperpolarization or repolarization currents (AHP). They then decay exponentially as described in Clopath et al. (2010)

| (4) |

where the subscript x can be f, referring to “fast” or s, referring to “slow.” τfahp (τsahp) (refers to the fast (slow) AHP decay time constant. The AHP currents are applied in addition to the soft firing threshold described above.

Synaptic input

The contribution of each input to the conductance change is modeled by an alpha function and the integration (from t = −∞ to ∞) of conductance change due to an input spike is kept constant by multiplication of an additional factor of . The total conductance change is modeled by linear summation of conductance change due to each presynaptic input spike.

| (5) |

where As are synaptic efficacies, τs are synaptic time constant and the subscript s can be chosen as e, referring to “excitatory” or i, referring to “inhibitory.” H(t) is the Heaviside step function. The times tj are referring to the timing of input spikes, which is assumed to have Poisson statistics.

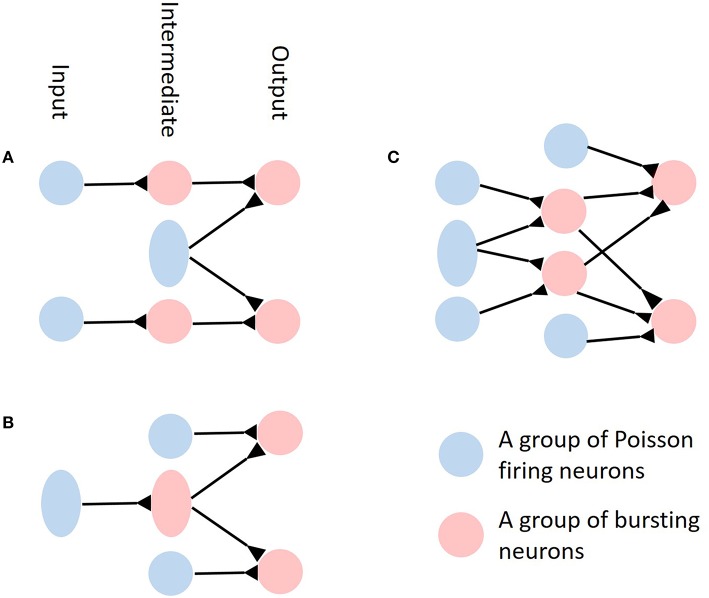

Input correlation

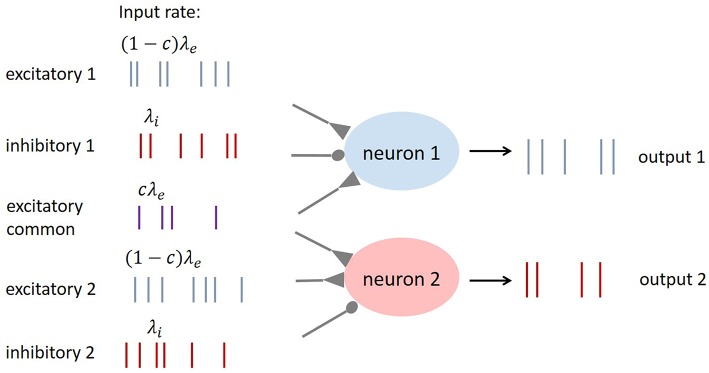

In order to add correlation to the input spike trains, we adopt the Single Interaction Process (Kuhn et al., 2003). Each neuron receives an independent excitatory spike train with input rate (1 − c)λe. In addition, both neurons receive a common excitatory spike train with input rate cλe. The total excitatory input rate is then λe and the pairwise spike count correlation coefficient between the spike trains received by each neuron is c. Inhibitory spike trains are not correlated in this work. The input structure is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The structure of input spike trains to the pair of neurons in study.

Balance between excitation and inhibition

Most neurons operate in the fluctuation driven regime, as evidenced by the highly variable inter-spike interval (ISI) in observed neural spike trains (Softky and Koch, 1993; Shadlen and Newsome, 1998). It means that excitation and inhibition are balanced. In this work, this is achieved by adjusting the inhibitory input rate λi such that the average output firing rate νout, calculated from a long time window of T = 1.5 × 106s, remains constant for various parameters. The reason for doing so is that output correlations are sensitive to the base-line firing rate of the post-synaptic neurons, as shown by de la Rocha et al. (2007).

Characterizing output correlations

To quantify the correlations of the output spike trains, we consider the cross-correlation function CCF(δt), given by

| (6) |

where nj(t) is the number of spikes per second in a spike train of the jth neuron. The value of the cross-correlation function has the physical meaning of “the number density of extra spike pairs (as a result of correlation) per second.” Here, “extra” compares to the case where the input is totally uncorrelated, and “spike pairs” here means the concurrence of two spikes, one from each neuron, fulfiling the condition that the spike from neuron 1 precedes that of the neuron 2 by δt, where the choice of neuron 1 and neuron 2 is arbitrary but fixed once it is made.

In order to further separate quantitatively output correlations from synchrony, we introduce two quantities, corr and sync, by integrating the area below the graph of CCF from time δt = −Tlarge to Tlarge and from δt = −Tsmall to Tsmall respectively, where Tlarge (Tsmall) is chosen to have a large (small) value.

| (7) |

| (8) |

These quantities correspond to the number of extra spike pairs per second (as a result of correlation) in the time window Tsmall and Tlarge, and hence describe the strength of output correlations and synchrony respectively.

Table 1 shows the parameters used in this work.

Table 1.

Parameters used in this work.

| Parameters | Value | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Neuron Dynamics | |||

| Vr | −70 | mV | |

| Ve | 0 | ||

| Vi | −75 | mV | |

| τm | 20 | ms | |

| 0.1 | |||

| 0.3 | |||

| τi | 8 | ms | |

| Input statistics | |||

| c | 0.2 | ||

| λe | 3000 (low), 60000 (high) | Hz | |

| νout | 8±0.03 | Hz | |

| Spiking mechanism (Sections Asymmetric Effects of Membrane Potential and Synaptic Integration Time Constants on Output Correlations and Slow Synaptic Filtering Induces Strong Burst Firing) | |||

| Vth | −50 | mV | |

| Vreset | −60 | mV | |

| trefract | 2 | ms | |

| Ifahpmax | 0 | ||

| Isahpmax | 0 | ||

| Spiking mechanism (Section Burst Firing Greatly Enhances Output Correlations) | |||

| Vspike | 0 | ||

| tdelay | 0.5 | ms | |

| Vthrest | −50 | ms | |

| λe = 3000 | λe = 60000 | ||

| Vthmax | −48.2 | −48.8 | mV |

| Ifahpmax | −1000 | −800 | mA |

| τfahp | 1 | variable | ms |

| Isahpmax | −40 | 0 | mA |

| τsahp | variable | N/A | |

| Correlation analysis | |||

| Tsmall | 1.1 | ms | |

| Tlarge | 10.1 | ms | |

Prevalence of burst firing

To quantify the prevalence of burst firing in a spike train, we use the probability distribution of the ISIs of an output spike train, and define the prevalence of burst firing (pburst) of a spike train as the probability of two consecutive spikes with their ISI being less than 16 ms, given as

| (9) |

where N(t) is the number of spikes in a spike train. Since the output firing rate is kept constant at 8 Hz (See Section Balance between Excitation and Inhibition), the ISI of spikes defined as a part of burst firing are smaller than one eighth of their mean. Such spikes can be considered to be significantly clustered.

Rank correlation between burst firing and output correlation

In order to quantitatively describe how much the increase of burst firing implies that of output correlations, we calculate Spearman's rank correlation ρ (Spearman, 1904) between pburst and corr that are obtained at various parameters, defined by

| (10) |

where n is the total number of pairs of data points in the data sets (of pburst and corr) and di is the difference in ranks between the ith data points in the two sets.

ρ describes the correlation of ranks between pburst and corr. If ρ takes a value close to 1 (-1), it means that corr is “almost” monotonically increasing (decreasing) with pburst. Otherwise, it means that the relationship between pburst and corr cannot be well fitted by a monotonic function.

Numerical methods

A finite difference method is used in integration. For all numerical integration, we used Heun's method, a second-order finite difference method, with time step △t = 0.02 ms.We interpolated spike times linearly within time steps for consistency (Shelley and Tao, 2001). The model is simulated for the time , including a transient period of ttran = 0.5s added before results are taken to allow transient effects of initial conditions to decay sufficiently. The bisection method is employed to adjust the inhibitory input rate λi in order to achieve constant output firing rate νout. Numerical simulations were carried out using our own custom programs written in C++.

Results

Asymmetric effects of membrane potential and synaptic integration time constants on output correlations

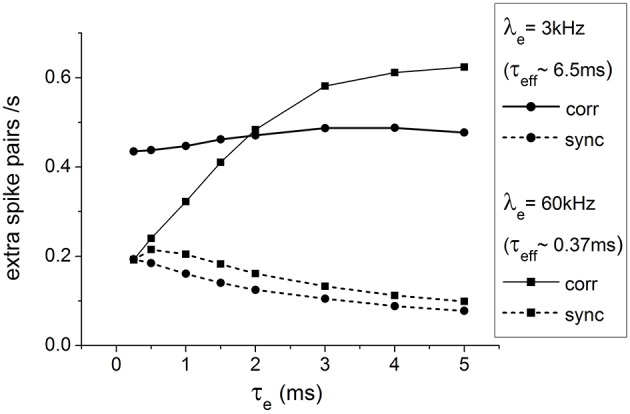

First, we simulated pairs of conductance-based LIF neurons receiving partially common inputs under different conductance states, characterized by the level of input activities λe, with various excitatory synaptic time constant τe in the absence of spike adaptation mechanisms (See Section Spiking Mechanism). Please note that we only consider cases in which neurons in the same pair have identical properties, i.e., λe and τe are the same for both neurons. The output correlations and synchrony, as quantified by corr and sync (See Methods), are obtained numerically. The results are shown in Figure 3. Many features of the dependence of output correlations and synchrony on τe and λe can be explained by considering the strength and the duration of the effects of an input spike on the membrane potential distribution (See Chan, 2015 for a detailed discussion and Rosenbaum and Josić, 2011 for the concept of “memory” of a spike).

How long the membrane potential is perturbed after an input spike has arrived, assuming small conductance fluctuations, mostly depends on the longer of the two time constants τe and τeff. When τe is large and τeff is small, charges take time to pass through the synapses but once they do, they cause a quick rise in the membrane potential. On the other hand, when τeff is large and τe is small, charges pass through the synapses quickly, but the membrane potential takes a longer time to rise. Based on this reasoning, the effect of a single input spike on the membrane potential for neurons with small τeff and large τe should be roughly similar to their counterparts with small τe and large τeff, and in a linear system this is true (Ostojic et al., 2009). If this intuition is sufficient to account for the process of correlation transfer in our model, the output correlations should be similar in these two scenarios.

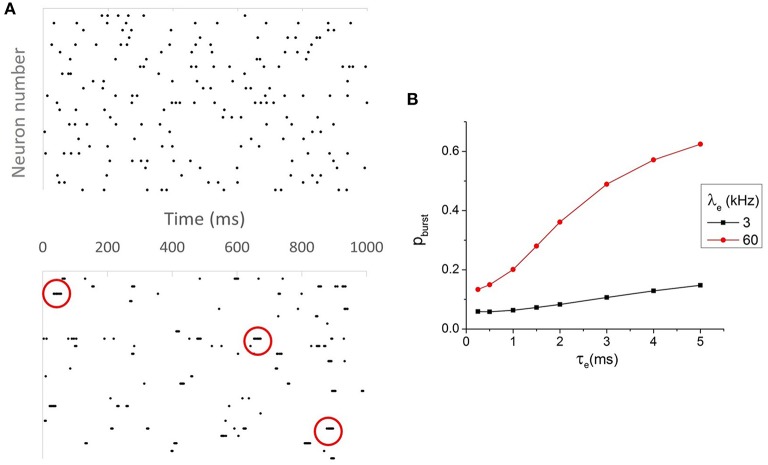

However, Figure 2 shows that when λe is high (τeff ≈ 0.37 ms), the output correlation increases drastically with τe such that at τe = 5 ms, the output correlation ends up well exceeding the output correlation in the case when λe is low (τeff ≈ 6.5 ms). This suggests that the effect of a single spike on the membrane potential alone cannot sufficiently account for such asymmetric effects of τeff and τe on output correlations.

Figure 2.

Output correlations and synchrony of spike trains of a pair of neurons receiving correlated input. When λe is high (τeff ≈ 0.37 ms and τe is large, the output correlation well exceeds the case when λe is low (τeff ≈ 6.5ms). Please refer to Section Characterizing Output Correlations for the meaning of corr and sync.

Slow synaptic filtering induces strong burst firing

A key difference between neurons with small τe and large τeff and neurons with small τeff and large τe is that for the former, an input spike can contribute to only a single output spike, while for the latter, an input spike can contribute to multiple output spikes, since synaptic ion channels do not close when the post-synaptic neuron fires. These multiple output spikes can take place within the time scale of the synaptic time constant, which is larger than the membrane time constant but still much smaller than the average inter-spike interval of spontaneous background activities. This phenomenon is commonly known as burst firing. Figure 3A shows the raster plot of output spike trains of neurons with small τe and large τeff (top) and their counterparts with large τe and small τeff (bottom). It is clear from visual inspection that the latter frequently exhibit burst firing while the former barely show any burst. To describe the prevalence of burst firing in a spike train quantitatively, we computed the value of pburst (see Methods) for pairs of neurons with different τe and τeff. pburst is indeed the greatest when τeff is small and τe is large, as shown in Figure 3B. Having established that burst firing distinguishes the scenarios of large and small τe and τeff, we hypothesize that the burst firing may contribute to the drastic increase of output correlations in the case of large τe, which is studied in the following section.

Figure 3.

(A) Raster plot for neurons with τe = 0.5 ms and τeff ≈ 6.5 ms (top) and τe = 4 ms and τeff ≈ 0.37 ms (bottom). Neurons with small τe and large τeff almost never fire bursts, while their counterparts with large τe and small τeff burst frequently. The red circles mark some of the instances of burst firing. (B) The prevalence of burst firing. Neurons with large τe and large λe (or small τeff) fire most frequently, as measured by pburst.

Burst firing greatly enhances output correlations

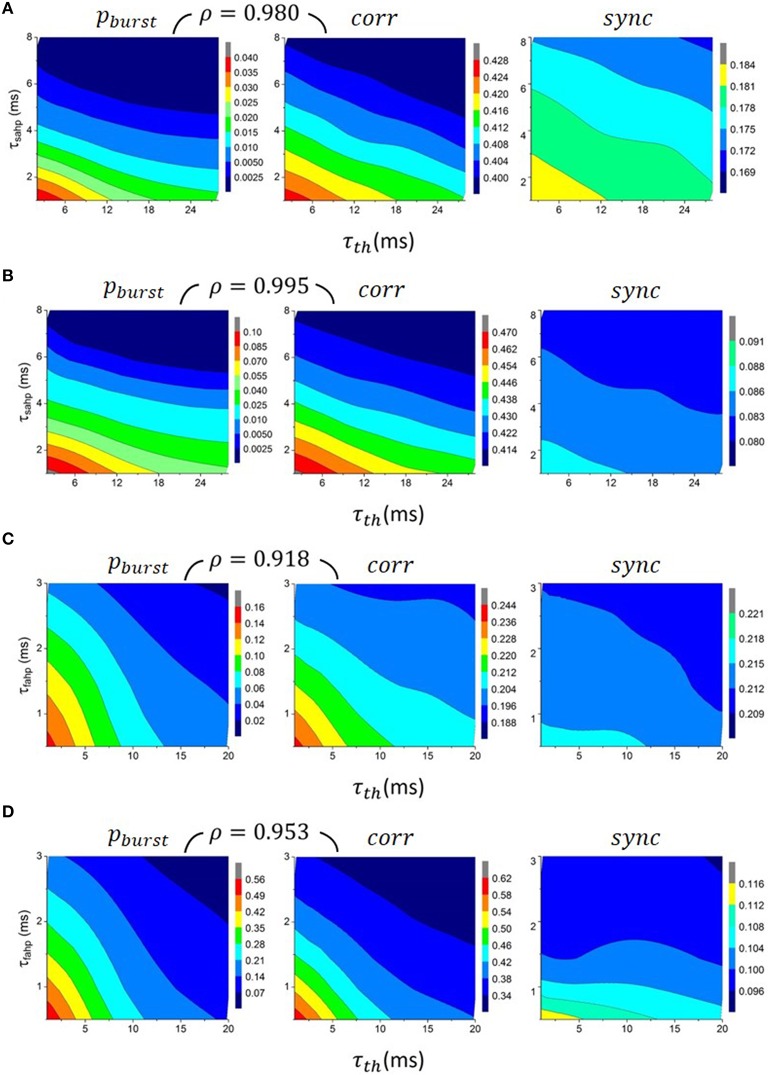

Biological neurons have various adaptation mechanisms, which prevent or reduce rapid repetitive firing when a neuron receives strong excitation. After-spike hyperpolarizing currents (Storm, 1987, 1990) and increased firing threshold after post-synaptic firing (Henze and Buzsáki, 2001; Platkiewicz and Brette, 2010) are two of them. We incorporated these effects into the conductance-based LIF model in the previous section by adding hyperpolarizing input currents (AHP) and raising the firing threshold after post-synaptic firing. The currents and the raised threshold would then decay to zero or their resting values with time constants τxahp and τth respectively, as described in the Methods. It is expected that increasing τxahp and τth would make it harder for neurons to fire again within a short period after each spike, and hence reduce the prevalence of burst firing. Figures 4A–D (left) shows that the pburst indeed decreases as τxahp and τth increase for neurons with different values of τe and τeff. When τxahp and τth are both large, pburst becomes very small, suggesting that under such conditions neurons hardly fire bursts.

Figure 4.

Dependence of the prevalence of burst firing pburst (left), output correlations corr (middle) and synchrony sync (right) on post-spike increase of firing threshold τth and on the time constants for AHP, τsahp (A,B) and τfahp (C,D). pburst decreases with all three, τsahp, τfahp and τth, and so does corr, and to a lesser extent, sync. Spearman's rank correlation ρ between pburst and corr, as shown above the contour plots, is very close to 1, which means that corr is “almost monotonically increasing” with pburst. (A) τeff ≈ 6.5ms, τe = 0.5 ms, (B) τeff ≈ 6.5 ms, τe = 4 ms, (C) τeff ≈ 0.37 ms, τe = 0.5 ms and (D) τeff ≈ 0.37 ms, τe = 4 ms.

If burst firing enhances output correlations, then increasing τxahp and τth should lead to a reduction of output correlations as bursts become increasingly rare. This is indeed shown to be true as illustrated in Figures 4A–D (middle). Output correlations are reduced most substantially after applying AHP currents and the variable threshold when τeff is small and τe is large, the case where the prevalence of burst firing would otherwise be the strongest. We have calculated Spearman's rank correlation coefficient ρ between pburst and corr for neurons with the same τe and τeff. It is very close to 1 regardless of τe and τeff. This suggests that output correlations are “almost monotonic increasing” with burst firing.

We next asked whether the increase of output correlations due to burst firing is mostly of a long time scale (correlations) or a short time scale (synchrony)? Figures 4A–D (right) shows that while sync in general also decreases with τxahp and τth, the scaling is much weaker than that for corr, both in terms of absolute value and percentage. Hence, we can conclude that burst firing strongly enhances output correlations, but only modestly enhances synchrony.

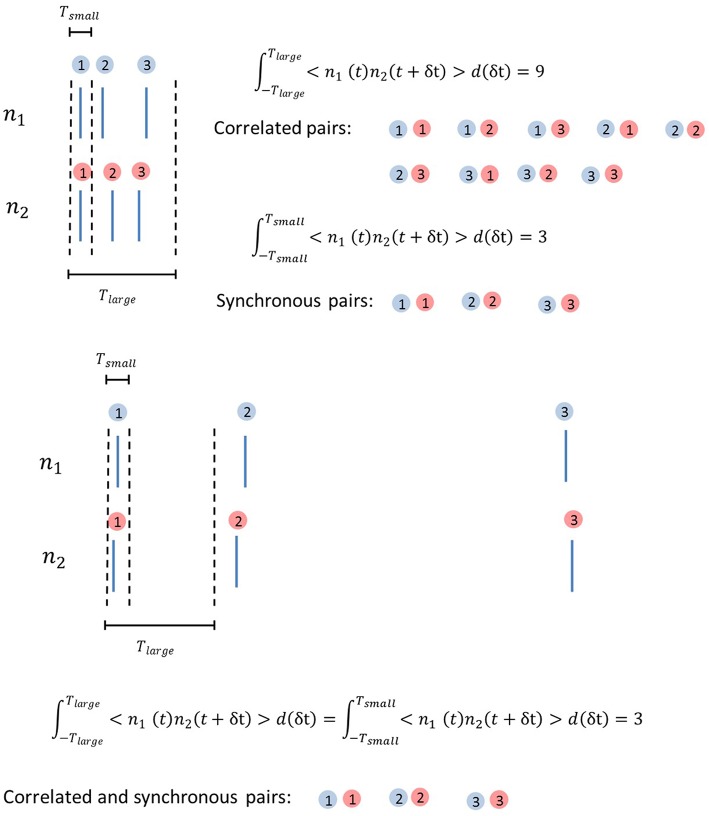

Before ending this section, we will provide some intuitive understanding on why burst firing enhances correlations. Output correlations are defined in Equation (11) as

| (11) |

The second term in Equation (11) is a constant. For the first term, the non-linearity of 〈n1 (t) n2 (t + δt)〉 and large integration time window mean that if the burst clusters of the two neurons align well, a spike in a burst cluster can simultaneously be correlated to several other spikes in the same cluster. This has a multiplicative effect on correlation. Without common input, the alignment of bursts due to chance is rare. Common inputs to both neurons enhance the alignment of burst clusters, introducing strong output correlations. For synchrony, the time window is too small for this to happen. This is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Illustration of why burst firing enhances correlation. Top, Correlated pairs and synchronous pairs in a burst cluster. Correlation is much enhanced due to one spike being correlated with multiple other spikes in the same burst cluster if they align well due to common inputs. Bottom, Correlated pairs and synchronous pairs with larger ISIs, having the same total number of spikes as in the top panel. The comparison of the results in the top and bottom panels shows how burst firing enhances correlation but not synchrony when neurons receive correlated input.

In this work, we only considered the case where c = 0.2. It has been shown in Chan (2015) that output correlation increases almost linearly with c in both the bursting and non-bursting cases up to c = 0.4. This suggests that our results should hold at least for positive value of c < 0.4.

Discussion

In this work, we first showed that neurons with slow synapses exhibit much stronger output correlations than their counterparts with fast synapses, which cannot be explained by only considering the perturbation of the membrane potential by a single input spike. We found that these neurons also exhibit strong burst firing. We showed that burst firing can be reduced by spike adaptation mechanisms, namely AHP and variable spiking threshold. Using them to modulate the amount of burst firing in neurons, we were able to study how burst firing affects output correlations independently of the synaptic time scale that causes the burst firing. From the resulting analysis we conclude that burst firing greatly enhances output correlations but only moderately enhances synchrony. This offers an explanation for our initial findings of strong output correlations in neurons with slow synapses.

Previous studies on effects of synaptic filtering and burst firing

Some previous work studied the effects of synaptic filtering on the output firing statistics analytically. Ostojic et al. (2009) considered how the time scale of synaptic filtering of a weak common input in the form of exponential excitatory post-synaptic currents (EPSCs) affects output correlations. However, in that work, the other input is assumed to be temporally uncorrelated. In such a case, the weak common input alone would not be strong enough to cause burst firing and hence the results are not comparable to our work in the regime of slow synaptic filtering. Moreno-Bote and Parga (2010) analytically derived output statistics including CCF for current-based LIF neurons with slow synapses but the role of synaptic filtering on correlation transfer remains unclear. Petrovici et al. (2013) managed to obtain expressions for the probability distribution of burst size and average inter-burst interval for neurons with slow synapses, but how such bursting influences correlation transfer remained unanswered. Our work is novel in that it provides links between burst firing and the ability of neurons to transfer correlations. These links suggest explanations why neurons with slow synapses exhibit unexpectedly strong output correlations when receiving common input, compared to their counterparts with fast synapses.

Is enhanced correlation by burst firing due to a transient increase of output firing rate?

It has been shown that output correlation increases with firing rate (de la Rocha et al., 2007). To compensate such effects, we have ensured that the overall average output firing rate was the same in all simulations by adjusting the amount of inhibitory input (See Section Balance between Excitation and Inhibition). However, the output firing rate as measured in a small time window, i.e., the instantaneous firing rate, is fluctuating because the timing of input spikes is stochastic. If we consider bursts to be short periods in which the instantaneous firing rate is very high, it therefore seems that the observed increase of output correlations is a forgone conclusion. However, because the mean firing rate is always kept the same, there are also long periods of relative quiescence between bursts when the instantaneous firing rate is very low compared to the non-bursting case. The momentary increase of correlation due to increased instantaneous firing rate during bursts might well have been offset by the long periods of reduced rate and hence reduced correlations during the quiescent periods between bursts. Our results show that this is not the case.

In other words, our results can be interpreted in the following way: given a constant mean firing rate, increasing the variance of the instantaneous firing rate transfers input correlations to higher output correlations.

Effects of burst firing on downstream neurons

We have shown that with correlated inputs, neurons who fire in bursts show stronger output correlations than those who do not, given they have the same synaptic and membrane time constants. In a biological neural network, the spike trains of neurons firing bursts may become input to downstream neurons. Such spike trains are non-Poisson with a high probability of having small ISIs (Ostojic, 2011). How then do these bursting, non-Poisson spike trains affect the correlation transfer in the downstream neurons? For neurons with both fast synaptic filter and short membrane integration time window, their excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) have a shorter time scale than the ISIs within a burst, which is bounded from below by the absolute refractoriness. Therefore, spikes within a burst are processed no different from other spikes and the correlation transfer should be little different from the case where the input obeys Poisson statistics.

If the time scale of either the synaptic filtering or membrane integration is slow, then there are at least three interesting scenarios to consider. In the first scenario, the bursting input to downstream neurons is independent and the downstream neurons receive additional, correlated Poisson input, as depicted in Figure 6A. We hypothesized that the downstream neurons would exhibit burst firing but such burst firing would be uncoordinated among neurons so would not have significant effects on output correlations. In the second scenario, the bursting spike trains are generated by neurons receiving independent inputs but they project to several downstream neurons, so becoming correlated inputs to the downstream neurons, as depicted in Figure 6B. In this case, the bursts would form a strong transient excitatory drive simultaneously to more than one downstream neuron, much like the correlated synchronous inputs in Schultze-Kraft et al. (2013). Therefore, we expect that like in that work, the output correlations and synchrony would be boosted. The last scenario would be the same as the previous scenario except that the bursting spike trains are generated by neurons already receiving correlated inputs, as depicted in Figure 6C. In this case, not only the bursts would drive the downstream neurons in coordination, but the resulting drive would also be much stronger than in the previous case since they arrive in synchrony. From the results of Schultze-Kraft et al. (2013) we hypothesize that the output correlation would be further strengthened compared to the previous case because of the increase of synchrony in the input. The role of burst firing on correlation transfer in more complex biological neural networks of multiple layers is an interesting direction for future work.

Figure 6.

Simplified illustrations of possible neural networks with correlated or uncorrelated bursting neurons and Poisson inputs. (A) Bursting spike trains are independent to downstream neurons while the downstream neurons receive additional, correlated Poisson input. In the diagram, blue circles represent groups of Poisson firing neurons while red circles represent groups of bursting neurons. Inhibitory connections are not shown in the diagram. (B) Neural network where the bursting spike trains generated by neurons receiving independent input constitutes the correlated input to downstream neurons. (C) Same as (B) but the bursting spike trains now receive correlated input and therefore are correlated themselves.

Burst firing and correlation transfer in biologically realistic neural networks with inhibition

In this work, we showed on the single neuron level that slow synaptic filtering gives rise to burst firing while spike adaptation mechanisms suppress it. In biological neural networks, interactions between excitation and inhibition may also contribute to the enhancement or suppression of burst firing. For instance, in networks with feedforward inhibition where input from a layer of neurons simultaneously excites the neurons in the output layer as well as inhibitory interneurons which are also connected to the above-mentioned neurons, output neurons can only fire within a few milliseconds after receiving strong excitatory input, as the strong excitation activates the interneurons which then silenced the output neurons (Pouille and Scanziani, 2001; Kremkow et al., 2010). This could result in the suppression of otherwise burst firing in the absence of inhibition. Indeed, it has been suggested that feedforward inhibition may be responsible for the transition between the burst firing state and the suppressed state in the subiculum (Sah and Sikdar, 2013).

Previous work has shown that feedforward inhibition (Middleton et al., 2012), as well as recurrent inhibition (Tetzlaff et al., 2012) and lateral inhibition (Giridhar et al., 2011), play important roles in modulating the level of correlation in neural networks by suppressing and reshaping the output correlations of neurons receiving correlated inputs. In light of it would be interesting to study whether and how burst firing is involved in the changes of output correlations observed in such inhibitory circuits.

Implication on neural coding

Neurons with slow synapses are integrators (König et al., 1996; Hong et al., 2012; Ratté et al., 2013). Previous work (Hong et al., 2012; Ratté et al., 2013) has shown that correlations of integrators arises from co-modulation of rate and is of long time scale, which is in agreement with the results the work presented here (See Figure 3). These previous studies further claimed that such correlations do not provide temporal information about the input and reduce coding efficiency through introducing redundancy. This is not so evident in our case where the correlations are mostly attributable to burst firing. Several experimental studies (Snider et al., 1998; Lesica and Stanley, 2004; Oswald et al., 2004; Eyherabide, 2008) and numerical studies (Kepecs and Lisman, 2003; Lesica and Stanley, 2004; Oswald et al., 2004) have shown that information may be represented in neural bursts. Transmission of information by bursts is advantageous since bursts can reliably produce output spikes (Snider et al., 1998), thereby reducing information loss when output neurons fail to produce spikes due to noise and synaptic failure (Krahe and Gabbiani, 2004). Moreover, input bursts can better produce precisely timed output than isolated spike (Kepecs and Lisman, 2003) such that correlated bursting spike trains may constitute precisely timed, synchronous input to downstream neurons. Therefore, the large correlation-to-synchrony ratio observed in neurons with slow synapses does not necessarily imply that such neurons cannot employ temporal based coding. It is possible that the presence of bursts actually facilitates information transmission through storing information in the bursts themselves or increasing the efficiency of other codes.

Author contributions

HC: Design the work, run the simulation, do the data analysis, produce the figures, write the manuscript. DY: Design the work, write the manuscript. CZ: Design the work, write the manuscript. TN: Write the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Human Frontiers Science Program (HFSP), grant number RGP0053/2015, Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) Strategic Development Fund, the Hong Kong Research Grant Council, grant number GRF12302914.

References

- Averbeck B. B., Latham P. E., Pouget A. (2006). Neural correlations, population coding and computation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 358–366. 10.1038/nrn1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair W., Zohary E., Newsome W. T. (2001). Correlated firing in macaque visual area MT: time scales and relationship to behavior. J. Neurosci. 21, 1676–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H. K. (2015). Impact of Synaptic Properties, Background Activities and Conductance Effects on Neural Computation of Correlated Inputs. MPhil Thesis. Hong Kong Baptist University. [Google Scholar]

- Clopath C., Büsing L., Vasilaki E., Gerstner W. (2010). Connectivity reflects coding: a model of voltage-based STDP with homeostasis. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 344–352. 10.1038/nn.2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rocha J., Doiron B., Shea-Brown E., Josić K., Reyes A. (2007). Correlation between neural spike trains increases with firing rate. Nature 448, 802–806. 10.1038/nature06028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diesmann M., Gewaltig M., Aertsen A. (1999). Stable propagation of synchronous spiking in cortical neural networks. Nature 402, 529–533. 10.1038/990101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipoppa M., Gutkin B. S. (2013). Correlations in background activity control persistent state stability and allow execution of working memory tasks. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 7:139. 10.3389/fncom.2013.00139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyherabide H. G., Rokem A., Herz A.V., Samengo I. (2008). Burst firing is a neural code in an insect auditory system. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2:3. 10.3389/neuro.10.003.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerkin R. C., Tripathy S. J., Urban N. N. (2013). Origins of correlated spiking in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 17083–17088. 10.1073/pnas.1303830110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giridhar S., Doiron B., Urban N. N. (2011). Timescale-dependent shaping of correlation by olfactory bulb lateral inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 5843–5848. 10.1073/pnas.1015165108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze D. A., Buzsáki G. (2001). Action potential threshold of hippocampal pyramidal cells in vivo is increased by recent spiking activity. Neuroscience 105, 121–130. 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00167-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S., Ratté S., Prescott S. A., De Schutter E. (2012). Single neuron firing properties impact correlation-based population coding. J. Neurosci. 32, 1413–1428. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3735-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepecs A., Lisman J. (2003). Information encoding and computation with spikes and bursts. Network 14, 103–118. 10.1080/net.14.1.103.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A., Smith M. A. (2005). Stimulus dependence of neuronal correlation in primary visual cortex of the macaque. J. Neurosci. 25, 3661–3673. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5106-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König P., Engel A. K. (1995). Correlated firing in sensory-motor systems. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 5, 511–519. 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80013-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König P., Engel A. K., Singer W. (1996). Role of the cortical neuron: integrator or coincidence detector? Trends Neurosci. 19, 130–137. 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)80019-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahe R., Gabbiani F. (2004). Burst firing in sensory systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 13–23. 10.1038/nrn1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremkow J., Aertsen A., Kumar A. (2010). Gating of signal propagation in spiking neural networks by balanced and correlated excitation and inhibition. J. Neurosci. 30, 15760–15768. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3874-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn A., Aertsen A., Rotter S. (2003). Higher-order statistics of input ensembles and the response of simple model neurons. Neural Comput. 15, 67–101. 10.1162/089976603321043702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn A., Aertsen A., Rotter S. (2004). Neuronal integration of synaptic input in the fluctuation-driven regime. J. Neurosci. 24, 2345–2356. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3349-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesica N. A., Stanley G. B. (2004). Encoding of natural scene movies by tonic and burst spikes in the lateral geniculate nucleus. J. Neurosci. 24, 10731–10740. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3059-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin-Kumar A., Oswald A.-M. M., Urban N. N., Doiron B. (2011). Balanced synaptic input shapes the correlation between neural spike trains. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7:e1002305. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton J. W., Omar C., Doiron B., Simons D. J. (2012). Neural correlation is stimulus modulated by feedforward inhibitory circuitry. J. Neurosci. 32, 506–518. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3474-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Bote R., Parga N. (2004). Role of synaptic filtering on the firing response of simple model neurons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92:028102. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.028102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Bote R., Parga N. (2010). Response of integrate-and-fire neurons to noisy inputs filtered by synapses with arbitrary timescales: firing rate and correlations. Neural Comput. 22, 1528–1572. 10.1162/neco.2010.06-09-1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun M., Lampl I. (2008). Instantaneous correlation of excitation and inhibition during ongoing and sensory-evoked activities. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 535–537. 10.1038/nn.2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostojic S. (2011). Interspike interval distributions of spiking neurons driven by fluctuating inputs. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 361–373. 10.1152/jn.00830.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostojic S., Brunel N., Hakim V. (2009). How connectivity,background activity, and synaptic properties shape the cross-correlation between spike trains. J. Neurosci. 29, 10234–10253. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1275-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald A.-M. M., Chacron M. J., Doiron B., Bastian J., Maler L. (2004). Parallel processing of sensory input by bursts and isolated spikes. J. Neurosci. 24, 4351–4362. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0459-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzeri S., Schultz S. R., Trevesa A., Rolls E. T. (1999). Correlations and the encoding of information in the nervous system. Proc. R. Soc. B 266, 1001–1012. 10.1098/rspb.1999.0736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovici M. A., Bill J., Bytschok I., Schemmel J., Meier K. (2013). Stochastic inference with deterministic spiking neurons, arXiv:1311.3211v1 [q-bio.NC]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Platkiewicz J., Brette R. (2010). A threshold equation for action potential initiation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6:e1000850. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F., Scanziani M. (2001). Enforcement of temporal fidelity in pyramidal cells by somatic feed-forward inhibition. Science 293, 1159–1163. 10.1126/science.1060342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratté S., Hong S., De Schutter E., Prescott S. A. (2013). Impact of neuronal properties on network coding: roles of spike initiation dynamics and robust synchrony transfer. Neuron 78, 758–772. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A. D. (2003). Synchrony-dependent propagation of firing rate in iteratively constructed networks in vitro. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 593–599. 10.1038/nn1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson M. J. E., Gerstner W. (2005). Synaptic shot noise and conductance fluctuations affect the membrane voltage with equal significance. Neural Comput. 17, 923–947. 10.1162/0899766053429444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum R., Josić K. (2011). Mechanisms that modulate the transfer of spiking correlations. Neural Comput. 23, 1261–1305. 10.1162/NECO_a_00116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah N., Sikdar S.K. (2013). Transition in subicular burst firing neurons from epileptiform activity to suppressed state by feedforward inhibition. Eur. J. Neurosci. 38, 2542–2556. 10.1111/ejn.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas E., Sejnowski T. J. (2000). Impact of correlated synaptic input on output firing rate and variability in simple neuronal models. J. Neurosci. 20, 6193–6209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas E., Sejnowski T. J., Medical H. H., Torrey N., Road P., Carolina N. (2001). Correlated neuronal activity. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 539–550. 10.1038/35086012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze-Kraft M., Diesmann M., Grün S., Helias M. (2013). Noise suppression and surplus synchrony by coincidence detection. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9:e1002904. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen M. N., Newsome W. T. (1998). The variable discharge of cortical neurons: implications for connectivity, computation, and information coding. J. Neurosci. 18, 3870–3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley M. J., Tao L. (2001). Efficient and accurate time-stepping schemes for integrate-and-fire neuronal networks. J. Comput. Neurosci. 11, 111–119. 10.1023/A:1012885314187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider R. K., Kabara J. F., Roig B. R., Bonds A. B. (1998). Burst firing and modulation of functional connectivity in cat striate cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 80, 730–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softky W. R., Koch C. (1993). The highly irregular firing of cortical cells is inconsistent with temporal integration of random EPSPs. J. Neurosci. 13, 334–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spearman C. (1904). The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 15, 72–101. 10.2307/1412159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein R. B. (1967). Some models of neuronal variability. Biophys. J. 7, 37–68. 10.1016/S0006-3495(67)86574-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm J. F. (1987). Action potential repolarization and a fast after-hyperpolarization in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J. Physiol. 385, 733–759. 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm J. F. (1990). Potassium currents in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Prog. Brain Res. 83, 161–187. 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61248-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff T., Helias M., Einevoll G. T., Diesmann M. (2012). Decorrelation of neural-network activity by inhibitory feedback. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8:e1002596 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J., Houweling A. R., Brecht M. (2010). Sparse and powerful cortical spikes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20, 306–312. 10.1016/j.conb.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohary E., Shadlen M. N., Newsome W. T. (1994). Correlated neuronal discharge rate and its implications for psychophysical performance. Nature 370, 140–143. 10.1038/370140a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]