Abstract.

We performed genetic analysis and clinical investigations for three patients with suspected monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) deficiency. On genetic analysis of the MCT8(SLC16A2) gene, novel mutations (c.1333C>A; p.R445S, c.587G>A; p.G196E and c.1063_1064insCTACC; p.R355PfsX64) were identified in each of three patients. Although thyroid function tests (TFTs) showed the typical pattern of MCT8 deficiency at the time of genetic diagnosis in all patients, two patients occasionally were euthyroid. A TRH test revealed low response, exaggerated response and normal response of TSH, respectively. Endocrinological studies showed gonadotropin (Gn) deficiency in two adult patients. On ultrasonography, goiter was detected in one patient. Interestingly, pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated atrophy and thinness of the pituitary gland in two patients. Our findings suggest that thyroid status in patients with MCT8 deficiency varies with time of examination, and repeated TFTs are necessary for patients suspected of MCT8 deficiency before genetic analysis. In addition, it is noteworthy that some variations were observed on the TRH test and ultrasonography of the thyroid gland in the present study. Morphological abnormality of the pituitary gland may be found in some patients, while Gn deficiency should be considered as one of the complications.

Keywords: MCT8(SLC16A2) gene, Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome, MCT8 deficiency, thyroid function, brain MRI

Introduction

Thyroid hormone (TH) is essential for normal brain development (1, 2). Bioavailability of T3 in the CNS is regulated by type II deiodinase in astrocytes that converts T4 to T3 and type III deiodinase in neurons that inactivates T4 to reverse T3 (rT3). Multiple transporters are involved in cellular iodothyronine uptake and efflux in different tissues (3, 4). Recent evidence has suggested that monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) is important for T3 uptake into central neurons (5,6,7).

The MCT8 (SLC16A2) gene is located on human chromosome Xq13.2. The six exons encode a protein of 613 or 539 amino acids that contains 12 putative transmembrane domains (TMDs) (5, 6). MCT8 is expressed in numerous human tissues, including the brain, heart, placenta, lung, kidney, skeletal muscle and liver (8,9,10). Recently, loss-of-function mutations in this gene have been reported worldwide in patients with X-linked mental retardation (XLMR) (11). Affected males are characterized by severe cognitive deficits, spastic or dystonic quadriplegia and axial hypotonia, a disorder also known as the Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (AHDS, OMIM 300523) (12,13,14). With respect to activities of daily living, development of speech is usually absent, and the majority of patients are unable to sit, stand or walk without support. Furthermore, the typical biochemical abnormalities include elevated T3 and decreased T4 levels in the presence of borderline-mildly increased TSH levels (14, 15). These findings indicate that MCT8 plays an essential role in the development of the CNS, most likely by facilitating the supply of TH to neurons.

In the present study, we describe three novel mutations in the MCT8(SLC16A2) gene in three male patients with AHDS. Additionally, new endocrinological and radiological characteristics are presented for these patients.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

The subjects were three male Japanese patients with a severe phenotype of AHDS at the Tokyo Metropolitan Kita Medical and Rehabilitation Center for the Disabled. Their clinical features are summarized below.

Patient 1: Patient 1 was an 8-yr-old boy with a clinical diagnosis of AHDS. There were two persons with mental retardation in his family or close relatives. Pregnancy was not complicated and uneventful delivery occurred at gestational age 41 wk and 1 d, with a birth weight of 2800 g (–0.48 SD) and length of 47.1 cm (–0.9 SD). His Apgar score was normal. At age 4 mo, he showed poor weight gain and hypotonia with poor head control. Thyroid function and creatinine kinase (CK) were normal at that time (data not shown). However, at age 6 mo, thyroid function tests (TFTs) showed serum levels of TSH, FT3 and FT4 of 3.1 μIU/ml, 6.5 pg/ml and 0.77 ng/dl. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at age 1 yr demonstrated delayed myelination. He showed poor feeding and never walked. At present, he shows severe mental retardation, poor head control, reduced muscle mass, hypotonia and short stature. His body length, weight and BMI (body mass index) are 108 cm (–3.0 SD), 10.5 kg (–3.0 SD) and 9.00 kg/m2 (< 3rd percentile), respectively. Recent TFTs revealed serum levels of TSH, FT3 and FT4 were 2.44 μIU/ml, 4.2 pg/ml and 0.6 ng/dl, respectively. The development of his external genitalia and pubic hair was Tanner stage I. His testicular volumes were 2 ml bilaterally after surgery for undescended testes. His bone age/chronological age was 7.1 yr/8.0 yr.

Patient 2: Patient 2 was evaluated at age 20 yr. There was no family history of thyroid disorders or delay in mental or motor development. Although fetal distress was observed in pregnancy, uncomplicated delivery occurred at gestational age 42 wk, with a birth weight of 3300 g (+ 0.83 SD) and length of 51.6 cm (+ 1.24 SD). His Apgar sore was normal. At age 3 mo, poor weight gain, hypotonia and poor head control were noted. Brain MRI showed delay in myelination at age 1 yr 7 mo. TFTs revealed euthyroid status at age 19 yr 2 mo. He was clinically diagnosed as having AHDS. At present, his body length, weight and BMI are 149 cm (–3.76 SD), 19.1 kg (–4.22 SD) and 8.60 kg/m2 (< 3rd percentile). Severe mental retardation, inadequate head control, reduced muscle mass, quadriplegia, short stature and large goiter were observed. Recent TFTs revealed serum levels of TSH, FT3 and FT4 of 48.5 μIU/ml, 6.1 pg/ml and 0.3 ng/dl, respectively. The development of his external genitalia and pubic hair was Tanner stage I. The testes were undescended. His bone age/chronological age was 13.4 yr/20.0 yr.

Patient 3: Patient 3 was evaluated at age 21 yr. There was one male person with severe mixed cerebral palsy in his family or close relatives, and this person died at age 7 yr due to pneumonia. Pregnancy and delivery were uneventful. Delivery occurred at gestational age 39 wk and 5 d, with a birth weight of 3374 g (+ 0.89 SD) and length of 49.0 cm (± 0 SD). His Apgar score was normal. Dystonic posture, poor weight gain and hypotonia with poor head control were obvious by age 4 mo. Brain MRI demonstrated delayed myelination at age 1 yr 8 mo and at age 3 yr. Seizures began at age 3 yr, and anticonvulsive medication was initiated. However, anticonvulsive medicine was discontinued at his mother’s request when he was 8 yr old. At age 19 yr, he had aspiration pneumonia, and a gastrostomy feeding tube was put in place. He was also diagnosed as having AHDS. At present, his body length, weight and BMI are 132 cm (–6.69 SD), 18.0 kg (–4.32 SD) and 10.3 kg/m2 (< 3rd percentile), respectively. Severe mental retardation, inadequate head control, reduced muscle mass, quadriplegia and short stature were observed. Recent TFTs revealed serum levels of TSH, FT3 and FT4 of 3.48 μIU/ml, 5.7 pg/ml and 0.6 ng/dl, respectively. The development of his external genitalia and pubic hair was Tanner stage I. His testicular volumes were 3 ml bilaterally. His bone age/chronological age was 13.4 yr/21.0 yr.

Methods

Genetic analysis of the MCT8 (SLC16A2) gene

The Institutional Review Board Committee of Tokyo Metropolitan Kita Medical and Rehabilitation Center for the Disabled approved this study. After informed consent was obtained from parents of each patient, genomic DNA of the probands and their parents was extracted from peripheral blood using a QIAGen Amp Blood Kit (QIAGEN K.K., Tokyo, Japan). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was then carried out using specific primers to amplify exons 1–6 of the MCT8 (SLC16A2) gene, encompassing the entire coding sequence. PCR fragments for each exon were analyzed by direct sequencing in both directions, using an ABI BigDye terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Primer sequences and PCR conditions were as described previously (13).

To predict functional effects for the missense mutations identified in the MCT8 (SLC16A2) gene, in silico analysis was performed by using PolyPhen-2 and SIFT algorithms.

Endocrinological studies

We regularly measured patient serum levels of TSH, FT3 and FT4. In addition, we measured serum levels of SHBG and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BAP) as markers of thyroid state in the liver and bone (16, 17), as well as serum levels of prealbumin and retinol binding protein (RBP) as markers of nutritional status. Serum TSH, FT3 and FT4 levels were determined using an electrochemiluminescence assay (ECLIA, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Serum SHBG and BAP levels were determined by IMMULITE SHBG 2000 (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Inc., USA) and chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA, Beckman Coulter Inc., Tokyo, Japan), respectively. Furthermore, serum prealbumin and RBP levels were determined by turbidimetric immunoassay (TIA, Nittobo Medical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and latex agglutination turbidimetry (LA, Nittobo Medical Co., Ltd.), respectively. The reference ranges were 0.62–4.90 μIU/ml in childhood (under age 6 yr) and 0.436–3.78 μIU/ml in adulthood for TSH, 2.91–4.70 pg/ml in childhood (under age 6 yr) and 2.1–4.1 pg/ml in adulthood for FT3, 1.12–1.67 ng/dl in childhood (under age 6 yr) and 1.0–1.7 ng/dl in adulthood for FT4, 31–167 nmol/l for SHBG (Tanner stage I), 3.7–20.9 μg/l for BAP, 22.0–40.0 mg/dl for prealbumin and 2.7–6.0 mg/dl for RBP.

Furthermore, to evaluate the pituitary function of each patient, GH stimulation tests, the TRH test, the GnRH test and the CRH test were performed. In GH stimulation tests, we used GH releasing peptide-2 (GHRP-2) and arginine as loading drugs.

Radiological studies

In order to investigate the changes in the cerebral cortex and white matter for our patients, brain MRI (1.5T Avanto Siemens) was performed. Furthermore, cervical echogram (LOSIQ S8 GE) and pituitary MRI (1.5T Avanto Siemens) were carried out in order to assess the size and shape of the thyroid and pituitary glands of each patient. Regarding the size of the thyroid gland, the width and thickness of each lobe were measured and compared with updated reference values of thyroid size according to sex and body surface area, which were recently reported by Suzuki et al. (18). Regarding the size of the pituitary gland, anteroposterior diameter and height were measured on T1-weighted sagittal images, and width was measured on T1-weighted coronal images (19).

Results

Genetic analysis of the MCT8 (SLC16A2) gene

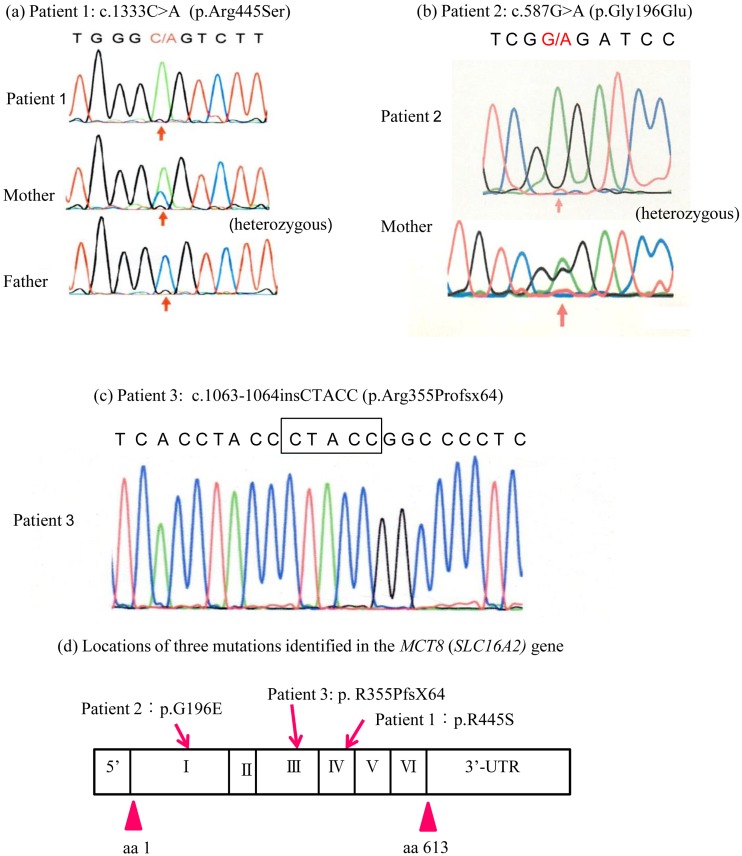

As shown in Fig. 1, genetic analysis of the MCT8 (SLC16A2) gene revealed different novel mutations in all patients. In patient 1, a missense hemizygous mutation in exon 4 (c.1333C>A; p.R445S) was identified. His mother was heterozygous for p.R455S. In patient 2, a missense hemizygous mutation in exon 1 (c.587G>A; p.G196E) was identified. His mother was also heterozygous for p.G196E. In patient 3, a hemizygous 5-base insertion in exon 3 (c.1063_1064insCTACC; p.R355PfsX64) was identified. Unfortunately, we were unable to analyze the mother of patient 3.

Fig. 1.

Molecular analysis of the MCT8 (SLC16A2) gene in the three patients. (a) Patient 1 was hemizygous for the c.1333C>A mutation in exon 4, resulting in an Arg445Ser (p.R445S) substitution located in the 8th transmembrane domain. His mother was heterozygous for the c.1333C>A mutation. (b) Patient 2 was hemizygous for the c.587G>A mutation in exon 1, resulting in a Gly196Glu (p.G196E) substitution located in the first extracellular domain. His mother was heterozygous for the c.587G>A mutation. (c) Patient 3 was hemizygous for the 5-base insertion (c.1063_1064insCTACC) in exon 3, resulting in p.R355PfsX64. (d) Locations of three mutations identified in the MCT8 (SLC16A2) gene.

In silico analysis showed that the p.R445S mutation was predicted to be possibly damaging by PolyPhen-2, with a score of 0.927, and to be damaging by SIFT, with a score of 0.000. On the other hand, the p.G196E mutation was predicted to be probably damaging by PolyPhen-2, with a score of 1.000, and to be damaging by SIFT, with a score of 0.002.

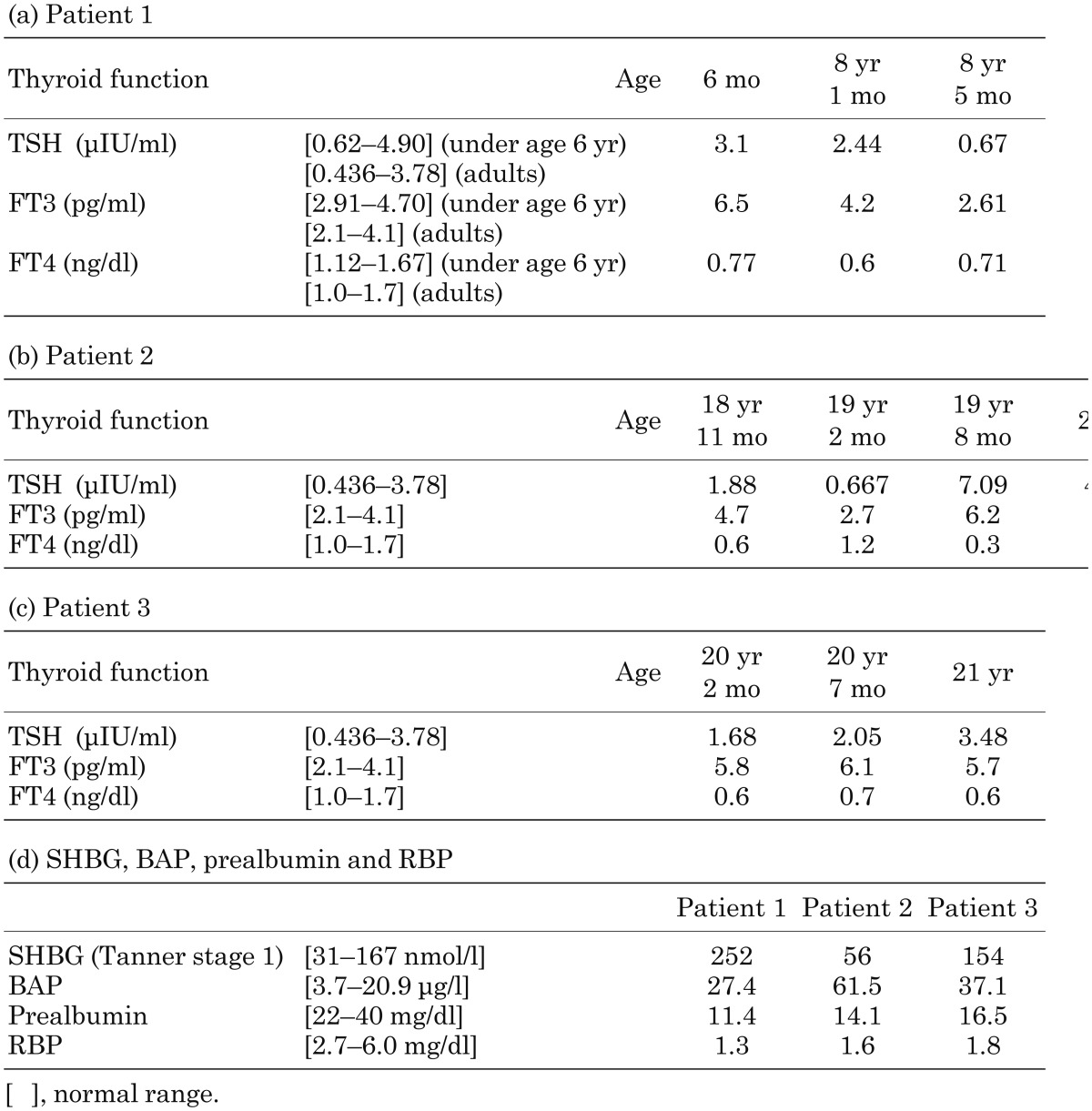

Thyroid function, SHBG, BAP, prealbumin and RBP

Thyroid function in the three patients over time is shown in Table 1. In all patients, serum TSH, FT3 and FT4 levels showed a typical pattern (elevated FT3, decreased FT4 and borderline-mildly increased TSH levels) for MCT8 deficiency at the time of genetic diagnosis. However, euthyroid status was observed in early infancy or adolescence in patients 1 and 2. A typical thyroid pattern for MCT8 deficiency was always observed in patient 3. On the other hand, the serum concentrations of SHBG and BAP were 252 nmol/l and 27.4 μg/l in patient 1, 56 nmol/l and 61.5 μg/l in patient 2 and 154 nmol/l and 37.1 μg/l in patient 3, respectively, at the time of genetic diagnosis (Table 1). Whereas the SHBG levels were elevated in only patient 1, the BAP levels were elevated in all patients. In the assessment of nutritional condition, serum concentrations of both prealbumin and RBP were decreased in all patients, reflecting extreme emaciation (BMI < 3rd percentile) (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of thyroid function, SHBG, BAP, prealbumin and RBP in the three patients.

Endocrinological stimulation tests

As shown in Fig. 2a, the TRH test revealed low response of TSH (pituitary hypothyroid pattern) in patient 1 (p.R455S), exaggerated response of TSH (primary hypothyroid pattern) in patient 2 (p.G196E) and normal response of TSH in patient 3 (p.R355PfsX64). In patient 1, the secretion of other anterior pituitary hormones was normal. GH deficiency was observed in patient 2 by GHRP-2 test and arginine tolerance test (Fig. 2b). The GnRH test showed low response in patients 2 and 3 (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 2.

Endocrinological stimulation tests. (a) TRH test in 3 patients. TSH response revealed a pituitary hypothyroid pattern in patient 1, primary hypothyroid pattern in patient 2 and normal pattern in patient 3. (b) Patient 2. GH deficiency was detected by GHRP-2 test and arginine tolerance test. The GnRH test showed a prepubertal response. (c) Patient 3. The GnRH test showed a prepubertal response.

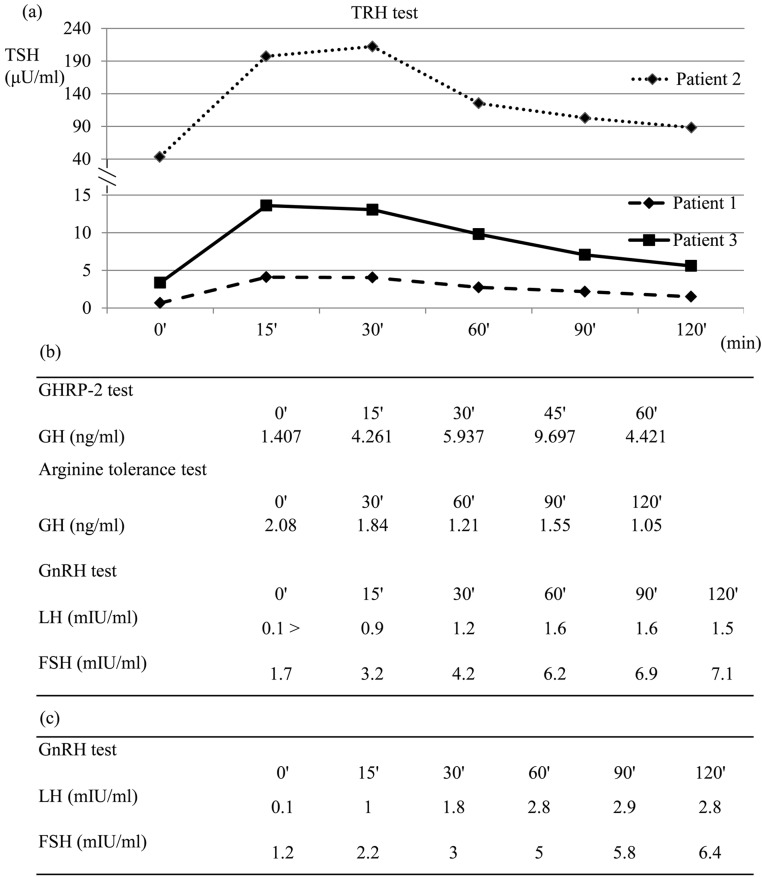

Brain and pituitary MRI

Brain MRI (T1- and T2-weighted, axial images) showed a delay in myelination at age 1 year in two patients (Fig. 3a, d) but normal myelination at the time of genetic diagnosis in all patients (Fig. 3b, c, e). Slight atrophy of the right frontal lobe in patient 1, atrophy of the temporal lobe and cerebellum in patient 2 and atrophy of the left cerebral hemisphere and frontal lobe in patient 3 were detected. Moreover, T1 shortening signals were detected in the bilateral globus pallidus and dentate nucleus of patients 2 and 3. Consequently, calcification was suspected.

Fig. 3.

Brain MRI (T1- and T2-weighted, axial images). (a, b) Patient 1 at age 1 yr (upper) and 8 yr (lower). At age 1 yr, delay in myelination was detected. At age 8 yr, slight atrophy of the right frontal lobe was demonstrated. (c) Patient 2 at age 20 yr. Atrophy of the temporal lobe and cerebellum was shown. T1 shortening signals were detected in the bilateral globus pallidus and dentate nucleus. (d, e) Patient 3 at age 1 yr (upper) and age 21 yr (lower). At age 1 yr, delay in myelination was detected. At age 21 yr, atrophy of the left cerebral hemisphere and frontal lobe was demonstrated. Furthermore, T1 shortening signals were detected in the bilateral globus pallidus and dentate nucleus.

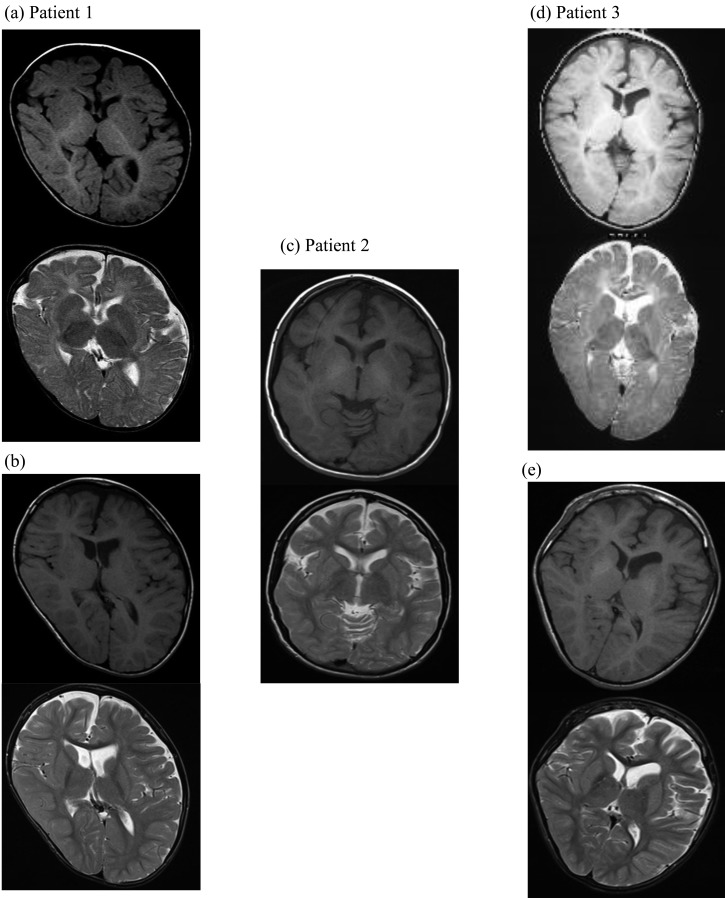

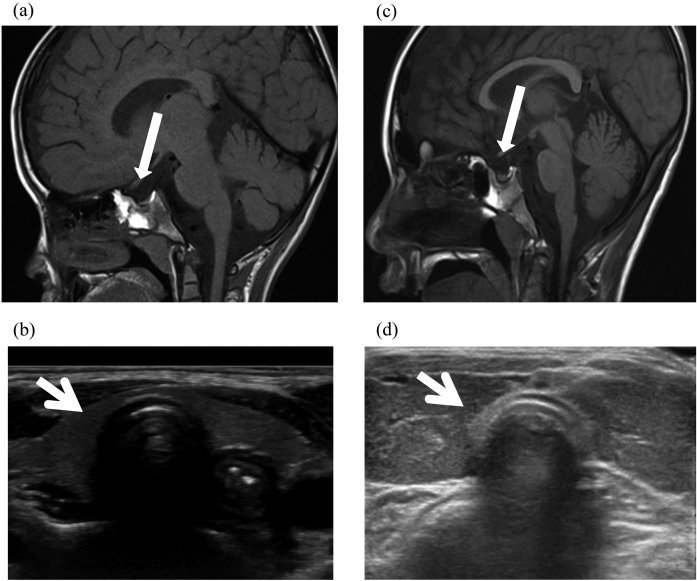

As shown in Fig. 4a and c, pituitary MRI (T1-weighted, sagittal images) demonstrated atrophy and thinness of the pituitary gland in patients 1 and 2. The anteropostrior diameter, height and width of the pituitary gland in patient 1 were 5.32 mm (–2.11 SD; 8.9 ± 1.7 mm (7–8 yr)), 1.41 mm (–3.39 SD; 4.8 ± 1.0 mm (7–8 yr)) and 9.85 mm (–2.65 SD; 12.5 ± 1.0 mm (7–8 yr)), respectively. Similarly, the anteropostrior diameter, height and width of the pituitary gland in patient 2 were 5.76 mm (–2.80 SD; 9.4 ± 1.3 mm (adults)), 2.9 mm (–2.38 SD; 6.7 ± 1.6 mm (adults)) and 10.66 mm (–1.28 SD; 14.0 ± 2.6 mm (adults)), respectively. The size and shape of the pituitary gland in patient 3 were normal (anteroposterior diameter, 6.76 mm (–2.03 SD); height, 4.72 mm (–1.24 SD); width, 11.95 mm (–0.79 SD)).

Fig. 4.

Pituitary MRI (T1-weighted, sagittal images) and ultrasonographic images of the thyroid gland in the two patients. (a, b) Patient 1 at age 8 yr. Atrophy and thinness of the pituitary gland were detected. The anteropostrior diameter, height and width of the pituitary gland were 5.32 mm (–2.11 SD; 8.9 ± 1.7 mm (7–8 yr)), 1.41 mm (–3.39 SD; 4.8 ± 1.0 mm (7–8 yr)) and 9.85 mm (–2.65 SD; 12.5 ± 1.0 mm (7–8 yr)), respectively. The widths and thicknesses of the right and left lobe of the thyroid gland were 9.15 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) and 10.42 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) (width), and 9.34 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) and 4.79 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) (thickness), respectively. (c, d) Patient 2 at age 20 yr. Atrophy and thinness of the pituitary gland and goiter were detected. The anteropostrior diameter, height and width of the pituitary gland were 5.76 mm (–2.80 SD; 9.4 ± 1.3 mm (adults)), 2.9 mm (–2.38 SD; 6.7 ± 1.6 mm (adults)) and 10.66 mm (–1.28 SD; 14.0 ± 2.6 mm (adults)), respectively. The widths and thicknesses of the right and left lobe of the thyroid gland were 19.6 mm (> 97.5 percentile) and 19.08 mm (> 97.5 percentile) (width), and 12.31 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) and 14.44 mm (> 97.5 percentile) (thickness), respectively.

Ultrasonography of thyroid gland

Cervical echogram showed that the widths of the right and left lobe were 9.15 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) and 10.42 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile), respectively, and that the thicknesses of the right and left lobe were 9.34 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) and 4.79 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile), respectively, in patient 1 (Fig. 4b). In patient 2, the widths and thicknesses of the right and left lobe were 19.6 mm (> 97.5 percentile) and 19.08 mm (> 97.5 percentile) (width) and 12.31 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) and 14.44 mm (> 97.5 percentile) (thickness), respectively (Fig. 4d). In patient 3, the widths and thicknesses of the right and left lobes were 12.32 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) and 9.65 mm (2.5–97.5 percentile) (width) and 12.82 mm (97.5 percentile) and 11.01 mm (97.5 percentile) (thickness), respectively. Accordingly, the thyroid size in patients 1 and 3 was normal, and goiter was recognized in patient 2.

Discussion

We identified three different novel mutations in the MCT8(SLC16A2) gene in three Japanese male patients with AHDS. All of them showed a severe phenotype of MCT8 deficiency. In 2004, Friesma et al. reported MCT8(SLC16A2) mutations in boys with severe XLMR and unusual abnormalities in thyroid function (15). Schwartz et al. also described mutations in six families with AHDS after the discovery that the MCT8(SLC16A2) gene plays a causal role in human disease (13). However, the prevalence, clinical extent including endocrinological and radiological features and genotype-phenotype correlations of MCT8 deficiency remain unclear (17).

In the present study, patient 1 had a 1333C>A mutation in exon 4, resulting in an Arg445Ser (p.R445S) substitution located in the 8th transmembrane domain (TMD). The Arg445 residue of the MCT8 protein is highly conserved among different species and in all members of the MCT family (20). Capri et al. reported a c.1333C>T transition (p.Arg445Cys) at the same position as ours in a patient with AHDS in 2013 (21). This patient displayed a moderate phenotype, as he was capable of walking with aid and pronouncing some words. Groeneweg et al. recently found that mutations in Arg445 or Asp498 that alter the local charge resulted in a near-complete loss of TH uptake capacity (20). They described the importance of a positive charge at position 445 and a negative charge at position 498. In their study, TH uptake by R445A and R445C (charged residues substituted with neutral residues) mutants was decreased in JEG3 cells. The p.R445S mutation, which was identified in patient 1, might affect TH uptake capacity because R445 is substituted with a neutrally charged Ser residue. Additionally, in silico analysis using PolyPhen-2 and SIFT also showed that this mutation would be pathogenic. Patient 2 had a 587G>A mutation in exon 1, resulting in a Gly196Glu (p.G196E) substitution located in the first extracellular domain between the first and second TMDs. In silico analysis using PolyPhen-2 and SIFT suggested that the p.G196E mutation may affect the function of MCT8 protein, being probably damaging. Patient 3 had a 5-base insertion in exon 3 (c.1063_1064insCTACC), resulting in p.R355PfsX64. Interestingly, this unique change created a frameshift starting from the cell domain directly under the 6th TMD, and a termination codon consequently appeared downstream. It is therefore speculated that the function of MCT8 would disappear via nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in the p.R355PfsX64 mutant. Based on the above results, our three patients were diagnosed as having MCT8 deficiency. Functional analysis of these mutations is necessary hereafter.

In order to further investigate the clinical features, we carried out endocrinological and radiological studies in our patients. Regarding thyroid function, as shown in Table 1, serum TSH, FT3 and FT4 levels showed typical patterns for MCT8 deficiency at the time of genetic diagnosis in all patients. However, both patients 1 and 2 were euthyroid in early infancy or adolescence. TRH test revealed a pituitary hypothyroid pattern (p.R445S), primary hypothyroid pattern (p.G196E) and normal pattern (p.R355PfsX64) of TSH in each patient. These findings indicate that thyroid function can vary based on the time of examination, and various patterns of TSH response caused by TRH stimulation were observed. Unlike our findings, previous reports described that the TRH test revealed normal response of TSH in some patients (22, 23). To assess the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis of patients with MCT8 deficiency in more detail, accumulation of endocrinological data including TRH test results will be essential. Moreover, serum SHBG levels, a marker of thyroid state in the liver, were elevated in patient 1, and serum BAP levels, a marker of thyroid state in bone, were elevated in all three patients. These results suggest that hyperthyroidism is present in the peripheral organs of patients with MCT8 deficiency (16, 17).

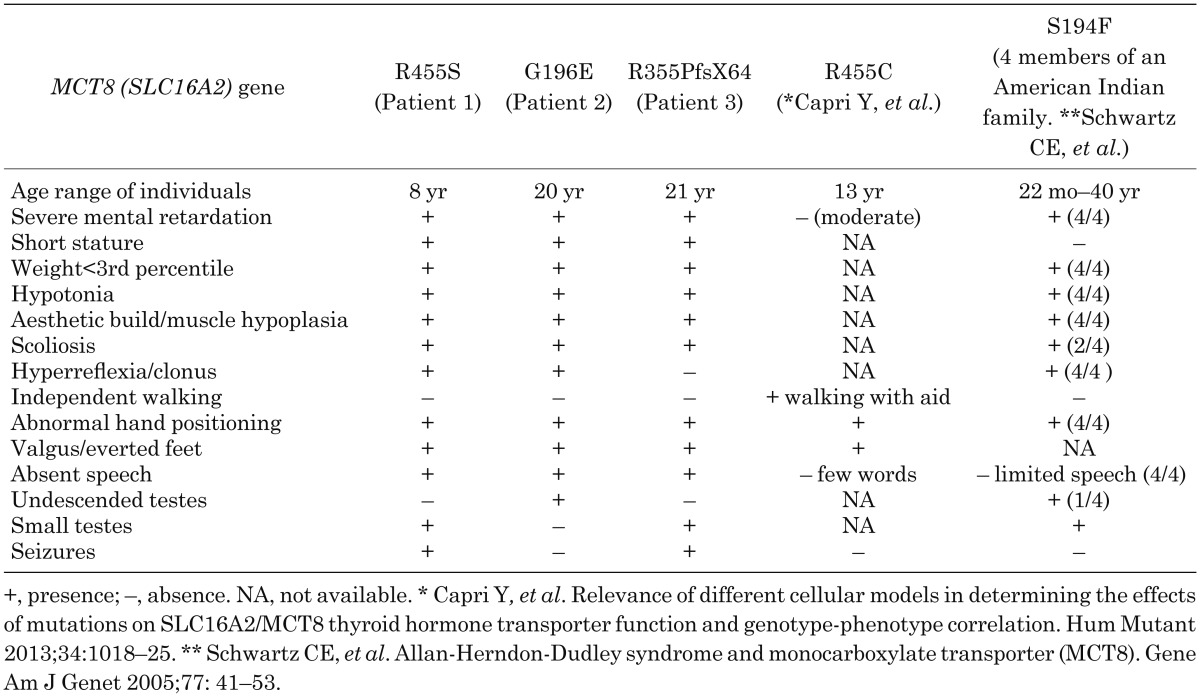

Other endocrinological stimulation tests demonstrated GH deficiency in one patient and Gn deficiency in two patients. Delayed puberty was clinically observed in the patients with Gn deficiency: however, severe short stature (height < –3.0 SD) and extreme emaciation (BMI < 3rd percentile) were seen in all of the patients. Schwartz et al. summarized the clinical findings for 32 patients in six families with AHDS, reporting that short stature (height < 3rd percentile), undescended testes and small testes (testis volume < 10 ml) were seen in four (17%) of 24 patients, two (8%) of 25 patients and three (18%) of 17 patients, respectively (13). Emaciation (weight < 3rd percentile) was seen in nineteen (66%) of 29 patients. Unfortunately, anterior pituitary function in these patients was not estimated. Clinical findings for our three patients and other foreign families with MCT8 gene mutations similar to ours are summarized in Table 2. From these comparisons, delayed puberty due to Gn deficiency is typical in MCT8 deficiency (13, 24). Regarding short stature, we speculate that it is probably associated with low nutritional condition and/or orthopedic problems, in addition to being an occasional complication of GH deficiency (23).

Table 2. Summary of clinical findings for our three patients and other families reported previously.

On radiological examination, cervical ultrasonography confirmed a normal thyroid in patients 1 (p.R445S) and 3 (p.R355PfsX64) and goiter in patient 2 (p.G196E) (Fig. 4). This finding in patient 2 was compatible with the pattern of TSH response in the TRH test. On the other hand, brain MRI demonstrated normal myelination at the time of genetic diagnosis in all patients, although a delay in myelination was detected in early childhood (Fig. 3). Namba et al. also described a patient carrying a novel c.1649delA mutation in the MCT8 gene on T2-weighted scans showing delayed myelination from infancy (23). Moreover, calcification was suspected in the bilateral globus pallidus and dentate nucleus at age 20 years in patients 2 (p.G196E) and 3 (p.R355PfsX64). Our findings suggest that improvement in delayed myelination and appearance of calcification in the brain may be observed with advancing age. Tonduti et al. recently pointed out extrapyramidal symptoms and delayed myelination as prominent features in MCT8 deficiency (25). According to their report, MRI follow-up in one case showed a marked delay in myelination at age 20 mo and slow progression of myelination reaching almost a normal pattern at age 5 yr 6 mo. Even if slow, the progression of myelination observed in brain MRI seems to have been confirmed in MCT8 deficiency (26). In addition, it is of interest that atrophy and thinness of the pituitary gland were seen in two patients and were accompanied by a hypothyroid response pattern of TSH in the TRH test (Fig. 4). To our knowledge, atrophy or thinness of the pituitary gland has never been reported in MCT8 deficiency. This may be a new clinical feature, although the association between pituitary morphology and the MCT8(SLC16A2) gene has not been clarified. It is therefore necessary to evaluate pituitary morphology by MRI and to accumulate data in patients with MCT8(SLC16A2) gene mutations.

Finally, our results support the notion that thyroid status in patients with MCT8 deficiency varies with time of examination: therefore, repeated TFTs are necessary for suspected patients before genetic analysis. It is also noteworthy that three patterns (pituitary hypothyroid, primary hypothyroid and normal patterns) can be observed with regard to the TSH response caused by TRH stimulation in MCT8 deficiency, and Gn deficiency should be considered a complication. Taken together, in addition to neurological examinations and TFTs, evaluation of anterior pituitary function and radiological investigation of the thyroid and pituitary glands would contribute to better understanding of MCT8 pathophysiology.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Prof. Hiroyuki Ida, Department of Pediatrics, The Jikei University School of Medicine, for fruitful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bernal J. Action of thyroid hormone in brain. J Endocrinol Invest 2002;25: 268–88. doi: 10.1007/BF03344003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.König S, Moura Neto V. Thyroid hormone actions on neural cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2002;22: 517–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1021828218454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visser WE, Friesema ECH, Jansen J, Visser TJ. Thyroid hormone transport by monocarboxylate transporters. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;21: 223–36. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2007.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser WE, Friesema ECH, Visser TJ. Minireview: thyroid hormone transporters: the knowns and the unknowns. Mol Endocrinol 2011;25: 1–14. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friesema ECH, Ganguly S, Abdalla A, Manning Fox JE, Halestrap AP, Visser TJ. Identification of monocarboxylate transporter 8 as a specific thyroid hormone transporter. J Biol Chem 2003;278: 40128–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300909200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafrenière RG, Carrel L, Willard HF. A novel transmembrane transporter encoded by the XPCT gene in Xq13.2. Hum Mol Genet 1994;3: 1133–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.7.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heuer H, Maier MK, Iden S, Mittag J, Friesema EC, Visser TJ, et al. The monocarboxylate transporter 8 linked to human psychomotor retardation is highly expressed in thyroid hormone-sensitive neuron populations. Endocrinology 2005;146: 1701–6. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price NT, Jackson VN, Halestrap AP. Cloning and sequencing of four new mammalian monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) homologues confirms the existence of a transporter family with an ancient past. Biochem J 1998;329: 321–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3290321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura M, Naito S. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiles of human solute carrier transporter superfamilies. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2008;23: 22–44. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.23.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herzovich V, Vaiani E, Marino R, Dratler G, Lazzati JM, Tilitzky S, et al. Unexpected peripheral markers of thyroid function in a patient with a novel mutation of the MCT8 thyroid hormone transporter gene. Horm Res 2007;67: 1–6. doi: 10.1159/000095805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friesema EC, Visser WE, Visser TJ. Genetics and phenomics of thyroid hormone transport by MCT8. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010;322: 107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allan W, Herndon CN, Dudley FC. Some examples of the inheritance of mental deficiency: apparently sex-linked idiocy and microcephaly. Am J Ment Defic 1944;48: 325–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz CE, May MM, Carpenter NJ, Rogers RC, Martin J, Bialer MG, et al. Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome and the monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) gene. Am J Hum Genet 2005;77: 41–53. doi: 10.1086/431313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumitrescu AM, Liao XH, Best TB, Brockmann K, Refetoff S. A novel syndrome combining thyroid and neurological abnormalities is associated with mutations in a monocarboxylate transporter gene. Am J Hum Genet 2004;74: 168–75. doi: 10.1086/380999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friesema EC, Grueters A, Biebermann H, Krude H, von Moers A, Reeser M, et al. Association between mutations in a thyroid hormone transporter and severe X-linked psychomotor retardation. Lancet 2004;364: 1435–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampl R, Kancheva R, Hill M, Bicíková M, Vondra K. Interpretation of sex hormone-binding globulin levels in thyroid disorders. Thyroid 2003;13: 755–60. doi: 10.1089/105072503768499644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visser WE, Vrijmoeth P, Visser FE, Arts WFM, van Toor H, Visser TJ. Identification, functional analysis, prevalence and treatment of monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) mutations in a cohort of adult patients with mental retardation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;78: 310–5. doi: 10.1111/cen.12023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki S, Midorikawa S, Fukushima T, Shimura H, Ohira T, Ohtsuru A, et al. Thyroid Examination Unit of the Radiation Medical Science Center for the Fukushima Health Management SurveySystematic determination of thyroid volume by ultrasound examination from infancy to adolescence in Japan: the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Endocr J 2015;62: 261–8. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ14-0478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin DH, Hamada T, Ishida O. Measurement of growth of pituitary gland with magnetic resonance imaging. Med J Kinki Univ 1996;21: 77–83(in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groeneweg S, Friesema ECH, Kersseboom S, Klootwijk W, Visser WE, Peeters RP, et al. The role of Arg445 and Asp498 in the human thyroid hormone transporter MCT8. Endocrinology 2014;155: 618–26. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capri Y, Friesema ECH, Kersseboom S, Touraine R, Monnier A, Eymard-Pierre E, et al. Relevance of different cellular models in determining the effects of mutations on SLC16A2/MCT8 thyroid hormone transporter function and genotype-phenotype correlation. Hum Mutat 2013;34: 1018–25. doi: 10.1002/humu.22331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuchs O, Pfarr N, Pohlenz J, Schmidt H. Elevated serum triiodothyronine and intellectual and motor disability with paroxysmal dyskinesia caused by a monocarboxylate transporter 8 gene mutation. Dev Med Child Neurol 2009;51: 240–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Namba N, Etani Y, Kitaoka T, Nakamoto Y, Nakacho M, Bessho K, et al. Clinical phenotype and endocrinological investigations in a patient with a mutation in the MCT8 thyroid hormone transporter. Eur J Pediatr 2008;167: 785–91. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0589-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wémeau JL, Pigeyre M, Proust-Lemoine E, d’Herbomez M, Gottrand F, Jansen J, et al. Beneficial effects of propylthiouracil plus L-thyroxine treatment in a patient with a mutation in MCT8. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93: 2084–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonduti D, Vanderver A, Berardinelli A, Schmidt JL, Collins CD, Novara F, et al. MCT8 deficiency: extrapyramidal symptoms and delayed myelination as prominent features. J Child Neurol 2013;28: 795–800. doi: 10.1177/0883073812450944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Knaap MS, Wolf NI. Hypomyelination versus delayed myelination. Ann Neurol 2010;68: 115. doi: 10.1002/ana.21751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]