Abstract

In oenology, the utilization of mixed starter cultures composed by Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts is an approach of growing importance for winemakers in order to enhance sensory quality and complexity of the final product without compromising the general quality and safety of the oenological products. In fact, several non-Saccharomyces yeasts are already commercialized as oenological starter cultures to be used in combination with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, while several others are the subject of various studies to evaluate their application. Our aim, in this study was to assess, for the first time, the oenological potential of H. uvarum in mixed cultures (co-inoculation) and sequential inoculation with S. cerevisiae for industrial wine production. Three previously characterized H. uvarum strains were separately used as multi-starter together with an autochthonous S. cerevisiae starter culture in lab-scale micro-vinification trials. On the basis of microbial development, fermentation kinetics and secondary compounds formation, the strain H. uvarum ITEM8795 was further selected and it was co- and sequentially inoculated, jointly with the S. cerevisiae starter, in a pilot scale wine production. The fermentation course and the quality of final product indicated that the co-inoculation was the better performing modality of inoculum. The above results were finally validated by performing an industrial scale vinification The mixed starter was able to successfully dominate the different stages of the fermentation process and the H. uvarum strain ITEM8795 contributed to increasing the wine organoleptic quality and to simultaneously reduce the volatile acidity. At the best of our knowledge, the present report is the first study regarding the utilization of a selected H. uvarum strain in multi-starter inoculation with S. cerevisiae for the industrial production of a wine. In addition, we demonstrated, at an industrial scale, the importance of non-Saccharomyces in the design of tailored starter cultures for typical wines.

Keywords: oenological non-Saccharomyces, wine alcoholic fermentation, Hanseniaspora uvarum, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, mixed fermentations, starter multi-strains, co-inoculation, sequential inoculation

Introduction

Fermentation associated with wine production represents complex biological processes denoted by several biochemical interactions between grape must and different micro-organisms such as fungi, yeasts and bacteria (Fleet, 2003). In particular, yeasts play a fundamental role, since they carry out the alcoholic fermentation (AF), i.e., the conversion of sugars to ethanol and CO2,but they also determine the wine organoleptic properties by producing and secreting into the fermenting must several secondary metabolites (Lambrechts and Pretorius, 2000; Fleet, 2003; Romano et al., 2003; Jolly et al., 2006). The AF is initially promoted by the action of a heterogeneous consortium of yeasts belonging to different non-Saccharomyces species usually characterized by a low fermentative power (Heard and Fleet, 1985), while its final step is under the control of alcohol-tolerant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains (Fleet and Heard, 1993). The function of non-Saccharomyces species throughout the AF is very significant, since they strongly contribute in determining the wine chemical composition. Autochthonous yeasts provide distinctive regional features to wines (Romano et al., 2003; Fleet, 2008; Ciani et al., 2010; Medina et al., 2013; Garofalo et al., 2015) thus advising their use as commercial starter cultures in order to differentiate wine productions. Some non-Saccharomyces yeasts are already commercialized as oenological starter cultures (e.g., Torulaspora delbrueckii, Metschnikowia pulcherrima, Pichia kluyveri, Lachancea thermotolerans) to be used in combination with Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Lu et al., 2015), while several others are the subject of various studies (e.g., Hanseniaspora uvarum, Starmerella bacillaris) (Masneuf-Pomarede et al., 2016).

The apiculate yeast Hanseniaspora uvarum (anamorph Kloeckera apiculata) is one of the yeast species more represented onto grape berries and they prevail in the first steps of spontaneous AF (Fleet and Heard, 1993). This yeast species is important in the production of volatile compounds in wine and the general chemical composition of wines made by Hanseniaspora spp./S. cerevisiae combinations may differ from reference wines produced with pure culture of S. cerevisiae (Zironi et al., 1993; Erten, 2002; Ciani et al., 2006; Gil et al., 2006). Previous reports indicated that several H. uvarum physiological properties of oenological interest are strain-dependent characters, such as ethanol production (Caridi and Ramondino, 1999), the volatile acidity associated with fermentation (Romano et al., 1992; Ciani and Maccarelli, 1998) and, most of all, the production of primary metabolites (i.e., glycerol, acetaldehyde) and secondary metabolites, such as ethyl acetate and hydrogen sulfide (Romano et al., 1997).

During a recent investigation, we have studied the oenological properties of 9 different H. uvarum strains isolated during the first 24 h of the spontaneous fermentation of Negroamaro grape must (De Benedictis et al., 2011). The chemical analysis of fermented must showed that all the strains produced low amounts of hydrogen sulfide and acetic acid, showing fructophilic character and relevant glycerol production. Analysis of volatile compounds indicated that in particular one strain, H. uvarum ITEM8795, could potentially enhance taste and flavor of wines, thus indicating its possible utilization for the formulation of mixed and/or sequential starters together with S. cerevisiae strains.

Indeed, for several non-Saccharomyces yeasts species has been demonstrated that they contribute to the analytical composition and the sensorial characteristics of wine, increasing the interest in the industrial application of apiculate yeasts (Pérez-Coello et al., 1999; Domizio et al., 2007; Fleet, 2008; Viana et al., 2008; Capozzi et al., 2015). In fact, the addition of non-Saccharomyces yeast species as part of mixed starter formulations, together with S. cerevisiae (and of malolactic bacteria), has been recently indicated as a way of mimic the spontaneous fermentations (Mendoza and Farías, 2010; Suzzi et al., 2012), conferring a particular aroma and characteristics to wines (Ciani et al., 2010; Comitini et al., 2011; Suárez-Lepe and Morata, 2012) without increasing/reducing the risks for wine quality and safety often associated with uncontrolled vinifications (Spano et al., 2010; Capozzi and Spano, 2011; Tristezza et al., 2013).

On the above basis, the aim of the present study was to assess the fermentation performances and interactions of mixed cultures and sequential inoculation of H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae. Data about microbial development, fermentation kinetics and secondary compound formation in lab-scale micro-vinification trials were further confirmed by utilization of the above mixed starter in pilot- and industrial-scale production of Negroamaro wine. At the best of our knowledge, the present investigation is the first report about the utilization of selected strain of H. uvarum in simultaneous and sequential co-fermentation with S. cerevisiae from micro-vinification up to the industrial scale in the production of a typical red wine.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains

Yeast strains used in the present study are deposited in Agro-Food Microbial Culture Collection of ISPA (http://www.ispacnr.it/collezioni-microbiche/). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain ITEM6920 (S) and the Hanseniaspora uvarum strains ITEM8795 (H1), ITEM8797 (H2), ITEM8799 (H3) have been previously isolated from spontaneous fermentation of Negroamaro grapes (De Benedictis et al., 2011; Tristezza et al., 2012). All the strains had been previously identified and characterized for their oenological properties, and in particular, the S. cerevisiae strain ITEM6920 has been already used as starter culture for the industrial production of Negroamaro wine (De Benedictis et al., 2011; Tristezza et al., 2012). The yeast strains were sub-cultured on YEPD (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L agar) and maintained at −80°C in glycerol 50% (Bleve et al., 2011). Screening of Killer-Sensitive pattern (killer, sensitive and neutral phenotypes) was carried out as described by Jacobs et al. (1988).

Microfermentations

Fermentation tests were carried out at 25°C in 500 mL flask containing 450 mL of Negroamaro grape must (205 g/L sugars, pH 3.44, assimilable nitrogen concentration 142.14 g/L) added with 20 mg/L of potassium metabisulphite. The must was clarified by centrifugation (10 min at 8000 g) and then sterilized by membrane filtration through Millipore system (0.45 μm membrane). Each flask was inoculated with the required concentration of a yeast pre-culture in the same must (48 h at 25°C), as previously described (Grieco et al., 2011).

The H. uvarum strains were inoculated at 107 CFU/mL, while the S. cerevisiae strain ITEM6920 was inoculated, in a preliminary test, at three different concentrations: 107, 105, and 103 CFU/mL, in order to reach, respectively, the inoculation ratios H. uvarum:S. cerevisiae of 1:1, 100:1, and 10,000:1. Each H. uvarum strain was inoculated in combination with the S. cerevisiae strain in two different timings: simultaneous inoculum (SM) and sequential inoculum (SQ). In the case of SQ, S. cerevisiae was inoculated after H. uvarum, when alcohol content reach 5% v/v. Fermentation kinetics were monitored daily by gravimetric determinations until constant weight and then the samples were stored at −20°C until analysis. Each fermentation experiment was carried out in duplicate. A pure culture of the S. cerevisiae strain was also inoculated as positive control, as well as a non-inoculated must was used as negative control.

Pilot-scale vinification

The selected strains were tested in pilot-scale fermentation trials. The vinification was carried out in an experimental cellar using sterile stainless steel 100-L vessels (Grieco et al., 2011) by inoculating 90 L of Negroamaro must (240 g/L of total sugars, 232 mg/L of yeast assimilable nitrogen, pH 3.52, added with 20 g/hL of potassium metabisulphite) with 107 cell/mL of H. uvarum and 105 cell/mL of S. cerevisiae, both in simultaneous and sequential approach. S. cerevisiae inoculated alone was used as control. The kinetics of the alcoholic fermentation process was monitored daily measuring the density. Samples of must and wines were collected as single replicate and stored at −20°C for further analyses.

Industrial vinification

Industrial fermentation was carried out in a 100,000 L stainless steel vessel. To start must fermentation on large scale, the initial inocula were prepared, transported to the winery and used as starters (Tristezza et al., 2012). The mixed starters cultures of Hanseniaspora uvarum strains ITEM8795 and S. cerevisiae ITEM6920, respectively corresponding to 7 × 1012 CFU/hL and 7 × 1010 CFU/hL, were mixed with 300 kg of and let for 6 h at room temperature. After this period, the yeast-must mixture was added to 7 tons of Negroamaro must (212.8 g/L of total sugars, pH 3.33, yeast assimilable nitrogen 158.8 g/L, added with 20 g/hL of potassium metabisulphite). The alcoholic fermentation process was carried out at 25°C and its kinetics was daily monitored by measuring the reducing sugars concentration and density. Samples of must and wines were collected as single replicate for further chemical and microbiological analysis.

Differential enumeration of yeast populations

In order to determine microbial growth, must and wine samples were collected over the fermentation processes. Serial dilutions of each sample were spread on WL Nutrient Agar (WLN medium, Oxoid, UK) and Lysine Agar (LA medium, Oxoid, UK). LA medium was used for the enumeration of non-Saccharomyces yeast population while WLN was used for differential enumeration of total yeast population (Pallmann et al., 2001). The identification of H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae was carried out by performing a molecular assay. Yeast colonies, showing a typical phenotype, were selected from WLN plates, and their genomic DNA was extracted according to Tristezza et al. (2009). RAPD pattern of H. uvarum were performed according to De Benedictis et al. (2011), while interdelta profiles of S. cerevisiae were analyzed as described by Tristezza et al. (2012).

Analytical determinations

The main chemical parameters of wines and musts were analyzed by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), employing the WineScan Flex (FOSS Analytical, DK). Samples were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min and then analyzed following the supplier's instructions. Acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate and acetoin were determined by gas-chromatography according to Mallouchos et al. (2003). The internal standard solution used was 4-methyl-1-pentanol. Free volatile compounds were extracted by solid phase extraction method (SPE) and analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) as previously described (Tufariello et al., 2012). The Odor Activity Values (OAVs) were calculated according to Capone et al. (2013). To evaluate the contribution of a volatile compound to the aroma, the Odor Activity Value (OAV) was calculated as the ratio between the concentration of each compound and the perception threshold in a specified matrix reported in literature (Swiegers et al., 2005). An aromatic series was defined as a group of volatile compounds with similar aroma descriptors (i.e., floral, sweet, fruity, spicy, green, fatty). The value of each aromatic series was calculated as the sum of the OAVs of the compounds that integrate it. Fermentation rate (FR), fermentation purity (FP), and alcohol yield coefficient (AYC) were calculated according to Tristezza et al. (2012).

Statistical treatment of data

Statistical data processing was performed using the free software package PAST (Hammer et al., 2001).

Results

Microfermentations

In a preliminary experiment we have studied the growth kinetics of the H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae mixed cultures (data not shown). The growth dynamics of the H. uvarum strains were comparable in the tests when the inoculum ratio were equivalent to 100:1 and 10.000:1, i.e., the S. cerevisiae starter inoculated at 105 and 103 CFU/mL, which reached a concentration of 107 CFU/mL respectively after 7 and 15 days. However, when the S. cerevisiae strain was inoculated at 107 CFU/mL (inoculum ratio of 1:1) the non-Saccharomyces cell concentration declined after 5 days (data not shown). For these reasons, the inoculum amount chosen for further experiments were 107 CFU/mL for H. uvarum strains and 105 CFU /mL for the S. cerevisiae starter (ratio 100:1). The fermentation kinetics of mixed cultures in micro-vinification trials are reported as Supplementary Data (Supplementary Figure 1). Two different temporal approaches were tested: a simultaneous inoculation of the two species and a sequential inoculation with a delay of 2 days in the addition of S. cerevisiae after H. uvarum. The time courses of simultaneous trials were comparable to those of the S. cerevisiae pure culture. The sequential trials presented a decrement of the initial fermentation rate that was higher for ITEM8797 (H2) and ITEM8799 (H3). Nonetheless, all trials gave complete fermentations in 14 days.

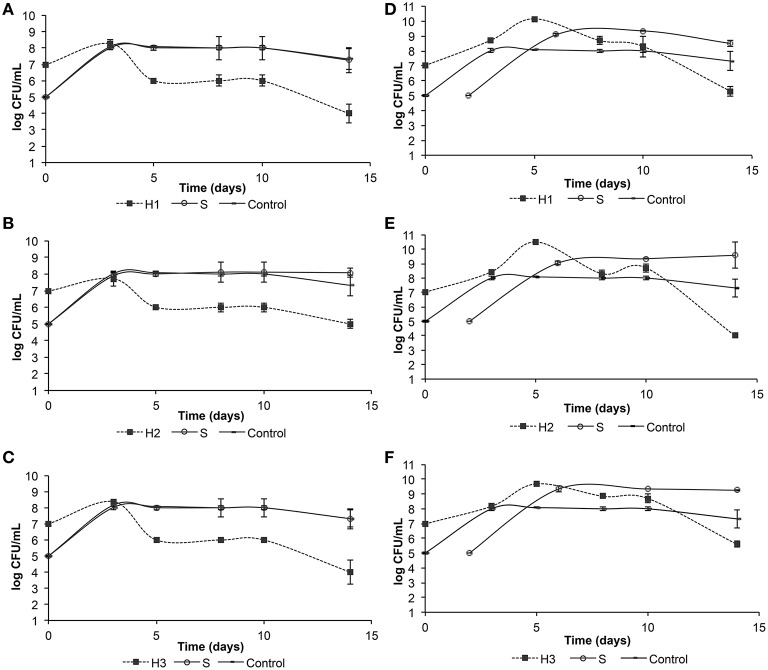

The microbial population dynamics of the mixed fermentations are shown in Figure 1. In all simultaneous trials (Figures 1A–C), both strains reached a maximum population (around 108 CFU/mL) after 72 h. Viable counts of S. cerevisiae kept stable at 108 CFU/mL until the 10th day of fermentation. Then, in mixed fermentation with ITEM8795 (H1) (Figure 1A) and H3 (Figure 1C), cells counts slightly decrease at 107 CFU/mL. From the 3rd to the 5th day, all the three H. uvarum strains decreased in viable counts at 106 CFU/mL and kept stable until the 10th day. At the end of the fermentations, the number of viable cells of H2 was 105 CFU/mL, whereas for H1 and H3 it was up to 104 CFU/mL. In the three sequential trials (Figures 1D–F), H. uvarum reached a maximum (1010 CFU/mL) in 5 days and then decreased at 109 CFU/mL. By the end of the fermentations, viable counts were 105 CFU/mL for H1, 104 CFU/mL for H2 and 106 CFU/mL for H3. The strain of S. cerevisiae showed a similar trend in the three trials: reached a maximum (109 CFU/mL) 3 days after inoculation and kept constant until the end of the fermentations. The pure culture of S. cerevisiae ITEM6920 (S) used as control reached a maximum population (108 CFU/mL) in 3 days and kept constant until the 10th day post-inoculation. By the 14th day, viable counts were 107 CFU/mL. Moreover, the tests carried out to assess the killer toxin activity excluded any cross inhibition between the H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae strains under study (data not show).

Figure 1.

Evolution of yeast populations in micro-vinification conditions with simultaneous inoculation (A, H. uvarum ITEM 8795 + S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920; B, H. uvarum ITEM 8797 + S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920; C, H. uvarum ITEM 8799 + S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920) and sequential inoculation (D, H. uvarum ITEM 8795 + S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920; E, H. uvarum ITEM 8797 + S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920; F, H. uvarum ITEM 8799 + S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920). Values are mean of two independent duplicates.

The oenological parameters of the mixed fermentations and the pure culture are shown in Table 1. As expected considering the fermentation kinetics, all the trials finished the fermentation leaving in the must less than 3 g/L of residual sugars. The highest ethanol concentration was determined in the pure culture of S. cerevisiae while all the mixed fermentations reached a lower ethanol concentration ranging from 11.92 to 12.19 mL/100 mL. On the other hand, the production of glycerol was greater (6.15–6.33 g/L) in mixed fermentations than in the control (5.24 g/L). The activity of H. uvarum did not increase volatile acidity; in fact the co-inoculated trials had a volatile acidity concentration statistically lower than the control. Fermentation purity (ratio between volatile acidity and ethanol produced) were also very low (0.03) for all samples, highlighting the good oenological performance of these mixed starters.

Table 1.

Concentration of major chemical compounds in fermented musts obtained with mixed cultures of H. uvarum /S. cerevisiae strains and with the pure culture of S. cerevisiae as control.

| Simultaneous | Sequential | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1+S | H2+S | H3+S | H1+S | H2+S | H3+S | S | |

| Alcohol (mL/100 mL) | 12.14±0.114 | 12.05±0.038 | 12.19±0.104 | 11.98±0.021 | 11.92±0.028 | 11.96±0.007 | 12.33±0.007 |

| Residual sugars (g/L) | 2.09±0.047 | 2.15±0.153 | 2.19±0.113 | 2.13±0.092 | 2.25±0.212 | 2.17±0.099 | 2.18±0.120 |

| Total acidity (g/L) | 6.30±0.029 | 6.43±0.087 | 6.46±0.083 | 6.35±0.064 | 6.52±0.014 | 6.49±0.028 | 6.34±0.035 |

| Volatile acidity (g/L) | 0.34±0.000 | 0.37±0.008 | 0.34±0.015 | 0.41±0.014 | 0.40±0.007 | 0.42±0.014 | 0.41±0.000 |

| pH | 3.34±0.005 | 3.33±0.014 | 3.33±0.008 | 3.32±0.007 | 3.31±0.007 | 3.31±0.000 | 3.29±0.000 |

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 1.87±0.029 | 1.80±0.068 | 1.92±0.143 | 1.63±0.028 | 1.66±0.042 | 2.11±0.092 | 1.73±0.078 |

| Glycerol (g/L) | 6.32±0.151 | 6.21±0.266 | 6.32±0.243 | 6.15±0.042 | 6.33±0.085 | 6.22±0.007 | 5.24±0.078 |

| Acetaldehyde (mg/L) | 20.05±0.451 | 19.96±0.382 | 20.32±0.297 | 21.4±0.600 | 21.95±0.190 | 22.41±0.216 | 24.22±0.164 |

| Ethyl acetate (mg/L) | 84.78±0.753 | 96.57±0.822 | 98.33±1.254 | 104.22±2.660 | 107.53±3.918 | 106.88±2.674 | 44.53±0.980 |

| Acetoin (mg/L) | 11.24±1.045 | 12.33±1.562 | 12.89±1.664 | 12.77±1.331 | 13.05±1.258 | 12.87±1.744 | 4.25±0.563 |

Values are the mean of two injections of each replicate; the standard deviation values (±) are indicated; n.d. not detectable.

The capacity to produce a number of volatile compounds susceptible to be involved in the wine flavor formation (acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate and acetoin) was also assessed in mixed fermentations (Table 1). The acetaldehyde, one of the most important carbonyl compounds synthetized all through the alcoholic fermentation, was detected, within the range between 11.24 mg/L (H1+S) and 12.89 mg/L (H3+S) for simultaneous inoculation and within the range between 12.77 mg/L (H1+S) and 13.05 mg/L (H2+S) for sequential inoculation. The free acetaldehyde has a dual role in flavor formation; at moderate concentrations it contributes to fruity flavors, while high levels (>200 mg/L) suppress the aroma in wines. The ethyl acetate was identified in concentrations ranging from 84.78 mg/L (simultaneous inoculum with H1+S) to 107.53 mg/L (sequential inoculum with H2+S). Ethyl acetate may add pleasurable, fruity aroma to the general wine bouquet at low concentrations, whereas it appreciably affect the final aroma at a content higher than 150 mg/L (Lambrechts and Pretorius, 2000). The acetoin (3-hydroxy-2-butanone) odor threshold is relatively high (150 mg/L) and, consequently, its sensory meaning for the global aroma is nearly irrelevant. All the H. uvarum strains under study produced a low amount of the above compound, either in the simultaneous and in the sequential inoculum, within the range of 11.24 mg/L (simultaneous inoculum with H1+S) to 13.05 mg/L (sequential inoculum with H2+S).

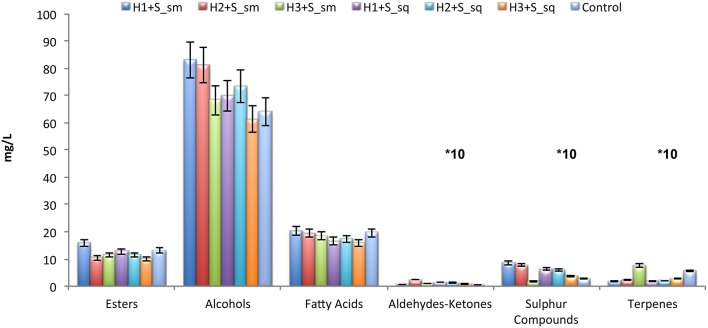

To determine the effect of co-inoculums and sequential yeasts on the final composition of wine, experimental wines were analyzed by gas chromatography. The comparison of the results obtained is shown in Figure 2. Generally, simultaneous trials produced a higher amount of volatile compounds, esters, alcohols and terpenes. The co-inoculated couple H1+S presented the highest formation of esters (15.7 mg/L), alcohols (83 mg/L), and organic acids (20.4 mg/L). Also the co-inoculated couple H2+S presented high concentrations of alcohols (81.2 mg/L) and organic acids (19.4 mg/L) but lower amounts of esters (10.3 mg/L).

Figure 2.

Volatile composition of wines obtained in micro-vinification conditions with simultaneous (sm) and sequential (sq) inoculation. H1, H. uvarum ITEM 8795; H2, H. uvarum ITEM 8797; H3, H. uvarum ITEM 8799; S, S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920. The pure culture of S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920 (S) was used as control. The concentrations of the aldeydes-ketones, sulfur compounds and terpenes have been multiplied by a factor of 10. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Analysis of these compounds provides a simply way of measuring the ability of different strains to produce wines with different profiles, since the main difference among wines inoculated with different yeast strains lies in the concentration of aromatic compounds rather than in the type of metabolite produced (Romano et al., 1997).

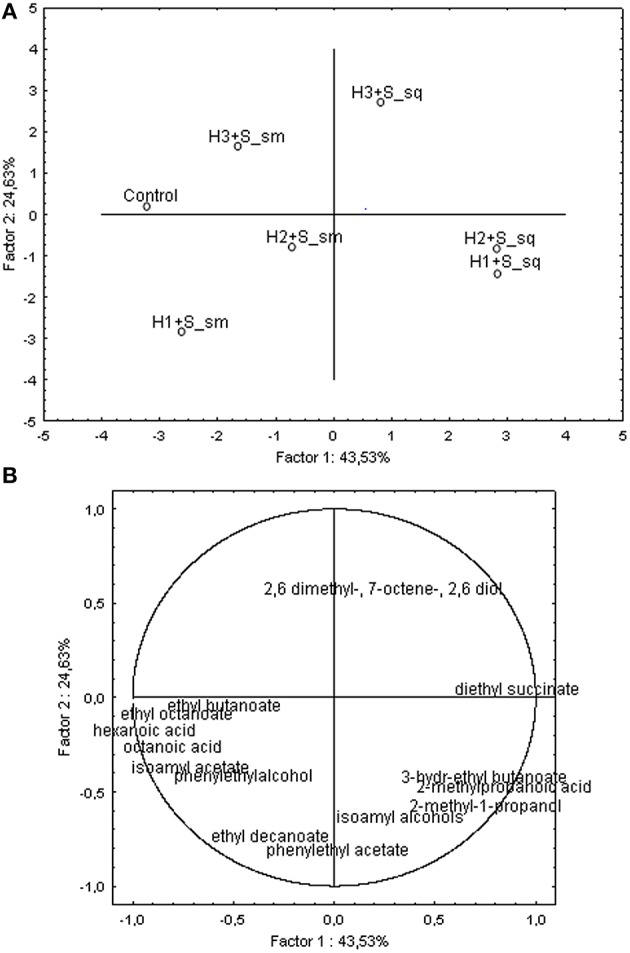

PCA was used to identify the specific volatile compounds best discriminating among the wines produced by co-inoculum (i.e., H1+S sm, H2+S sm, H3+S sm) and sequential (i.e., H1+S sq, H2+S sq, H3+S sq) techniques studied (Figure 3). PCA was initially applied to the concentrations of the volatile compounds in concentrations higher than their odor threshold are mainly considered as aroma-contributing substances (Gómez-Mínguez et al., 2007). The two principal components, PC1 and PC2, accounted for 68.16% of the total variance (43.53 and 24.63%, respectively). The second dimension (24.63% of explained variance) discriminates these two techniques studied, simultaneous (sm) and sequential (sq) inoculum.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional principal component analysis (PCA). Scores plot (A) for wines obtained in micro-vinification conditions and loading plot (B) for volatiles higher than odor threesold. Simultaneous (sm) and sequential (sq) inoculation. H1, H. uvarum ITEM 8795; H2, H. uvarum ITEM 8797; H3, H. uvarum ITEM 8799; S, S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920.

However, samples H2+S sm, was associated to negative PC1(34% of explained variance), that discriminates H2+S sm and H1+S sm from the two other samples, Control S and H3+S sm for the high content, besides other variables, of ethyl octanoate, ethyl butanoate, terpens responsible of floral and fruity notes. The sample H1+S sm clustered at negative PC1 and PC2 scores thus showed relatively high correlations mainly with hexanoic and octanoic acids, phenylethylalcohol and isoamyl acetate. Samples H1+S sq and H2+S sq that cluster at positive PC1 scores scored high relative correlations with diethyl succinate, 2-methyl-propanoic acid, 2-methyl-1-propanol and 3-hydroxy-ethyl butanoate. Finally, H3+S sq that clusters at positive PC2 associated to 2,6-dimethyl-7-octen-2,6 diol. In conclusion, it was found that cultures in co-inoculum positively influenced the production of different classes of volatiles, terpenes, esters, acids and alcohols. In particular H1+S sm was characterized by a higher yield of most volatile components that influence positively aroma bouquet, such as isoamyl acetate, ethyl octanoate, phenylethyl acetate (fruity notes), phenylethylalcohol (floral notes), hexanoic and octanoic acids.

Pilot-scale vinification

In reason of the performances in the micro-vinification trials, the Hanseniaspora uvarum strain ITEM8795 (H1) was selected to be tested in pilot-scale fermentations, both in simultaneous and sequential approaches, with S. cerevisiae ITEM6920. An identical amount (90 L) of the same Negroamaro must was inoculated with S. cerevisiae alone as control. Fermentation rate was higher for the two mixed starter fermentations than for that inoculated with the S. cerevisiae pure culture. Co-inoculation of H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae lead to a complete fermentation after 6 days (not shown). The three fermentations resulted in a different profile of sugars consumption (Supplementary Figure 2 in the Supplementary Data section). As can be observed, the simultaneous inoculation showed a good fermentation performance which led to a complete consumption of glucose in 4 days and fructose in 8 days. In addition, the sequential inoculation showed good fermentation properties with a complete consumption of glucose in 6 days and 5.7 g/L of residual fructose by the 12th day. On the contrary, the pure culture of S. cerevisiae showed a less efficient profile of sugar consumption with a complete consumption of glucose in the 8th day of fermentation and a residual fructose of 7.2 g/L at day 12. The development of yeast populations during the three fermentations is shown in Supplementary Figure 3 (Supplementary Data). The H. uvarum strain reached its maximum (108 CFU/mL) at the 2nd day, both in simultaneous and sequential trials; then, viable cells counts decreased at 103 CFU/mL (day 4th), subsequently at 102 CFU/mL, by the 6th day, and kept stable until the 11th day.

Viable cells counts of S. cerevisiae in simultaneous fermentation reached their maximum (108 CFU/mL) at the 2nd day and then slightly decreased at 107 CFU/mL until the end of fermentation (11th day). In sequential inoculation, S. cerevisiae reached a maximum population (109 CFU/mL) in 4 days and then gradually decreased. By the 11th day, viable counts were 107 CFU/mL. The pure culture of S. cerevisiae used as control showed a similar trend: reached a maximum (109 CFU/mL) 4 days after inoculation and constantly decreased to 107 CFU/mL until the end of the fermentations.

The analytical SPE/GC–MS method, used in this work for the analysis of wine samples, allowed the correct identification and quantification of 45 volatile compounds (Table 2). All the volatile compounds were grouped according to the belonging class (esters; aldehydes/ketons; alcohols; phenols; lactones; terpenes; acids). For each compound, the odor threshold (OTH) and the sensory odor descriptor were also reported. With respect to esters, it is important to highlight that wine produced by co-inoculation contained high concentrations of ethyl butyrate, isoamyl acetate, ethyl hexanoate responsible of fruity notes. On the contrary, concentrations of diethyl succinate, ethyl 9-decenoate, 2-phenylethyl acetate and diethyl malate were significantly lower in wines from co-inoculation assays. Ethyl esters are mainly synthesized by yeast starting from grape precursors and by ethanolysis of acylCoA that is formed during fatty acid synthesis or degradation.

Table 2.

Concentration of major volatile compounds in fermented musts obtained with the mixed starter H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae used in sequential or simultaneous inoculum.

| Volatile compounds | Odor threshold (μg/L)a | Odor descriptor | Odorant seriesb | H1+S Simultaneous | H1+S Sequential | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/L | μg/L | μg/L | ||||

| ESTERS | ||||||

| Ethyl butyrate | 20 (a) | Fruity | 1 | 425 ± 77 | 319 ± 84 | 386 ± 5 |

| Isoamyl acetate | 30(c) | Banana | 1 | 2535 ± 1 | 2239 ± 140 | 2235 ± 49 |

| Ethyl hexanoate | 14 (b) | 1 | 645 ± 118 | 561 ± 26 | 510 ± 17 | |

| Ethyl lactate | 154,636 (c) | Acid. medicine | 6 | 1028 ± 459 | 720 ± 104 | 1006 ± 32 |

| Ethyl caprilate (octanoate) | 5 (b) | Sweet. fruity | 1.4 | 548 ± 111 | 573 ± 74 | 406 ± 42 |

| 3-hydroxy. ethyl butyrate | 20,000 (b) | Caramel. Toasted | 4 | 52 ± 34 | 65 ± 10 | 52 ± 2 |

| Ethyl (decanoate) caprate | 200 (c) | Sweet. fruity | 1.4 | 219 ± 56 | 252 ± 71 | 188 ± 27 |

| Diethyl succinate | 200,000 (b) | Vinous | 7 | 3735 ± 1820 | 4216 ± 1820 | 3851 ± 212 |

| Ethyl 9 decenoate | 14,100 | 200 ± 46 | 234 ± 88 | 102 ± 6 | ||

| 2-phenyl ethyl acetate | 250 (a) | Floral | 2 | 598 ± 93 | 696 ± 125 | 517 ± 65 |

| Diethyl malate | 760,000 (b) | Over-ripe. peach. cut grass | 1 | 340 ± 164 | 525 ± 310 | 291 ± 31 |

| 4 hydroxy-3 methoxy benzoic acid ethyl ester (ethyl vanillate) | 990 (b) | Sweet. vanillin | 4.5 | nd | 4855 ± 21 | Nd |

| Ethyl monosuccinate | 1,000,000 (c) | Caramel. coffee | 4 | 5648 ± 318 | 6052 ± 552 | 8476 ± 311 |

| TOTAL | 15,975 ± 3296 | 21,306 ± 3405 | 18,021 ± 799 | |||

| CARBONYL COMPOUNDS | ||||||

| Acetaldehyde | 500 (a) | Pungent. ripe apple | 1.6 | 269 ± 21 | 155 ± 65 | 125 ± 7 |

| Acetoin | 150,000 | 538 ± 192 | nd | 544 ± 26 | ||

| Furfural | 14,100 (c) | nd | nd | nd | ||

| Benzaldehyde | 350 (c) | Sweet. fruity | 1.4 | 94 ± 35 | 70 ± 6 | 58 ± 6 |

| TOTAL | 901 ± 248 | 224 ± 71 | 728 ± 38 | |||

| ALCOHOLS | ||||||

| 1-propanol | 830 (b) | 1.6 | 312 ± 33 | nd | 211 ±17 | |

| Isobutanol | 40,000 (b) | 3.6 | 966 ± 566 | 701 ± 362 | 1427 ± 13 | |

| 1-butanol | 150,000 (b) | Medicinal. phenolic | 6 | 109 ± 9 | nd | 178 ± 7 |

| Isoamyl alcohol | 30,000 (a) | Burnt. alcohol | 4.6 | 14,785 ± 3772 | 13,968 ± 3525 | 15,754 ± 201 |

| 3-methyl-1-pentanol | 50,000 (c) | Vinous. herbaceous. cacao | 1.3.7 | 124 ± 43 | 118 ± 21 | 142 ± 7 |

| 1-hexanol | 8000 (a) | Flower. green. cut grass | 2.3 | 492 ± 196 | 491 ± 220 | 776 ± 22 |

| (E)-3-hexen-1-ol | 55 ± 31 | 79 ± 14 | 81 ± 5 | |||

| (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol | 400 (a) | 3 | 66 ± 21 | 80 ± 2 | 56 ± 14 | |

| 2.3-butanediol (levo) | 15,0000 (b) | Fruity | 1 | 2712 ± 1238 | nd | 1063 ± 48 |

| 2.3-butanediol (meso) | fruity | 820 ± 79 | nd | 296 ± 30 | ||

| Methionol | 1000 (a) | Cooked vegetable | 7 | 196 ± 82 | 203 ± 0 | 261 ± 8 |

| Benzylalcohol | 200,000 (b) | Sweet. fruity | 1.4 | 190 ± 20 | 184 ± 30 | 179 ± 16 |

| Phenylethylalcohol | 10,000 (a) | Floral. roses | 2 | 11,577 ± 2399 | 12,962 ± 3194 | 13,760 ± 1186 |

| TOTAL | 31,939 ± 8488 | 28,786 ± 7367 | 34,184 ± 1574 | |||

| PHENOLS | ||||||

| Guaiacol | 10 (c) | Sweet. smoke | 4.6 | 108 ± 22 | nd | nd |

| Eugenol | 6 (c) | Spices. clove. honey | 4.5 | nd | 142 ± 62 | 42 ± 13 |

| Ethyl phenol | nd | nd | nd | |||

| 4 vinyl guaiacol | 40 (a) | Spices. curry | 5 | 363 ± 151 | 248 ± 54 | 218 ± 24 |

| 4 Hydroxy methyl acetophenone | nd | 163 ± 42 | nd | |||

| Siringol | 299 ± 80 | 148 ± 0 | ||||

| TOTAL | 770 ± 231 | 553 ± 158 | 408 ± 37 | |||

| LACTONES | ||||||

| Y-butyrolactone | 35 (c) | Sweat. toasted | 4 | 175 ± 116 | 96 ± 37 | 174 ± 10 |

| Cis methyl 4 octanolide | 67 | 4 | nd | nd | 89 ± 3 | |

| TOTAL | 175 ± 116 | 96 ± 37 | 262 ± 13 | |||

| TERPENS | ||||||

| Terpineol | 110 | 2 | 73 ± 1 | 50 ± 0 | 30 ± 12 | |

| TOTAL | ||||||

| ACIDS | ||||||

| Isobutyric acid | 2300 (b) | Rancid. butter. cheese | 6 | 166 ± 138 | 93 ±31 | 212 ± 24 |

| Butyric acid | 173 (b) | Rancid. cheese. sweat | 6 | 115 ± 50 | 83 ± 14 | 85 ± 3 |

| (3 methyl butanoic) isovaleric acid | 33 (c) | Sweet. acid | 4.6 | 244 ± 58 | 269 ± 105 | 434 ± 10 |

| Hexanoic acid | 420 (b) | Sweet | 6 | 2366 ± 96 | 2161 ± 67 | 2159 ± 115 |

| Octanoic acid | 500 (c) | Sweet. cheese | 6 | 4716 ± 372 | 4372 ± 1098 | 3922 ± 149 |

| Decanoic acid | 1000 (b) | Rancid. fat | 6 | 1178 ± 10 | 1344 ± 13 | 1278 ± 121 |

| TOTAL | 8785 ± 725 | 8322 ± 1328 | 8090 ± 422 | |||

The pure culture of S. cerevisiae was used as control.

Values expressed in μg/L are the mean of two injections. The standard deviation values (±) are indicated. n.d. not detectable.

Odorant series: 1 = Fruity; 2 = Floral; 3 = Green; 4 = Sweet; 5 = Spicy; 6 = Fatty; 7 = Others.

Because alcohols are also important compounds influencing wine aroma, it is important to highlight that wine produced by co-inoculation contained higher 1-propanol, 1-butanol and isoamyl alcohols concentrations. Among identified alcohols, 2-phenylethanol was the second most abundant alcohol at concentrations higher than its threshold in all wines, contributing with fine rose's notes to wine aroma. In wines analyzed, we observed differences in α-terpineol concentration; in fact, this compound was identified and quantified in a major concentration in co-inoculated wine. Within the family of fatty acids, isobutyric, isovaleric, hexanoic, hexanoic, octanoic and decanoic acids were notable for their high concentrations in all wines and have been described with fruity, cheese, fatty, and rancid notes (Rocha et al., 2004).

The two mixed fermentations show an overall more complex aromatic profile than the pure culture of S. cerevisiae. Its sweet, spicy, floral odorant notes characterized the sequential mixed fermentation. Simultaneous fermentation of H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae was characterized by fruity and sweet aroma descriptors (Table 2).

Industrial vinification

These large-scale experiments were conducted in a winery cellar of Salento by simultaneous inoculation, with the selected mixed starter H. uvarum ITEM8795/S. cerevisiae ITEM6920, of 7 tons of Negroamaro must. The data corresponding to the fermentation performance of the two isolates used and their ability to dominate the fermentation indicated that these two autochthonous yeast strains possess the fundamental properties required for starter cultures, in fact, the fermentations progressed regularly and sugar depletion was accomplished in 10 days.

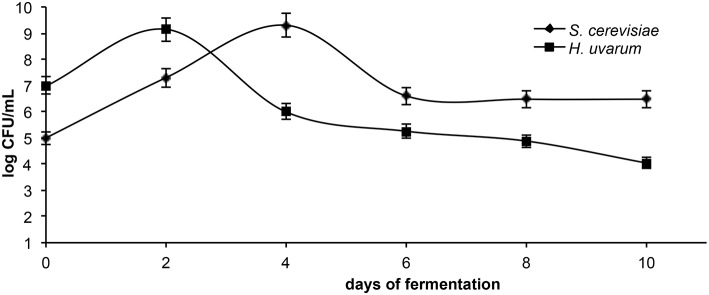

Viable cells counts of the two yeast species throughout the fermentation are shown in Figure 4. H. uvarum dominated the early stages of fermentation and its population reached the maximum (109 CFU/mL) at the 2nd day; then gradually decreased to 104 CFU/mL and keep stable until the end of the fermentation period. S. cerevisiae dominate the fermentation from day 4th, when it reached a concentration of 109 CFU/mL; then slightly decreased to 106 CFU/mL and ultimate the fermentation by day 8.

Figure 4.

Viable cell counts of the two inoculated yeast species throughout the industrial vinification.

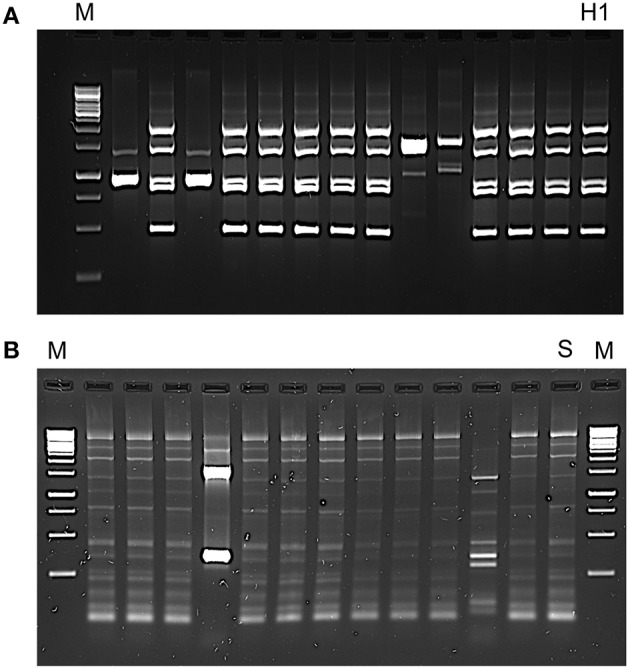

The dominance of the inoculated strains was confirmed by molecular analysis. The electrophoresis patterns of green colonies isolated on WLN agar at middle fermentation stage are shown in Figure 5A. It can be observed that 9 out of 13 isolates have the same profile than that of the inoculated starter H. uvarum ITEM 8795 (H1), thus indicating that this strain got the upper hand of indigenous non-Saccharomyces strains. Likewise, the electrophoresis patterns of pale cream colonies isolated on WLN agar at the end of the fermentation are shown in Figure 5B. In this case, the 83% of isolates exhibit an identical profile to the one of the inoculated starter S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920, it being the evidence that the above starter was able to dominate the final steps of the AF. The results of chemical analysis of the wine obtained by co-fermentation H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae are shown in Table 3, in comparison to the same must fermented with the commercial starter in use in the winery. The total acidity was higher in must fermented by mixed starter (5.84 g/L), while volatile acidity was lower (0.43 g/L) than in must fermented with the commercial S. cerevisiae (5.49 and 0.45 g/L, respectively). Both starters were able to metabolize completely sugars. Furthermore, the mixed starter showed a lower alcohol content (13.99 mL/100 mL).

Figure 5.

Electrophoretic profiles patterns of (A) RAPD analysis with primer RM13 of Hanseniaspora uvarum randomly isolated from the large scale fermentation. The strain-specific profile of the 8795 strain is reported (H1); (B) interdelta region patterns obtained from Saccharomyces cerevisiae randomly isolated at the end of the large scale fermentation. The strain-specific profile for the 6920 strain is reported (S). Molecular marker (M): Thermo Scientific GeneRuler 1 Kb DNA Ladder.

Table 3.

Analysis of final wine obtained by cofermentation of H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae in comparison to the same must fermented with the commercial starter in use in the industrial vinification.

| Compound | Cofermentation H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae | Commercial starter |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol (mL/100 mL) | 13.99 ± 0.003 | 14.03 ± 0.01 |

| Residual sugars (g/L) | n.d. | n.d. |

| Total acidity (g/L) | 5.84 ± 0.067 | 5.49 ± 0.028 |

| Volatile acidity (g/L) | 0.43 ± 0.005 | 0.45 ± 0.003 |

| pH | 3.48 ± 0.009 | 3.44 ± 0.003 |

| Malic acid (g/L) | 1.1 ± 0.008 | 0.96 ± 0.005 |

| Lactic acid (g/L) | 0.18 ± 0.034 | 0.17 ± 0.023 |

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 2.34 ± 0.105 | 1.89 ± 0.021 |

| Citric acid (g/L) | 0.45 ± 0.011 | 0.43 ± 0.02 |

| Density (g/mL) | 0.99093 ± 0.00003 | 0.99025 ± 0.000043 |

| Dry matter (g/L) | 22.79 ± 0.112 | 21.11 ± 0.111 |

| Glycerol (g/L) | 7.07 ± 0.014 | 7.01 ± 0.038 |

| Methanol (mL/100 mL) | n.d. | n.d |

| Total polyphenols (mg/L) | 547 ± 92 | 671 ± 25 |

| Anthocyanins (mg/L) | 410 ± 71 | 180 ± 22 |

| Absorbance at 420 | 0.88 ± 0.001 | 0.81 ± 0.028 |

| Absorbance at 520 | 0.97 ± 0.001 | 1.11 ± 0.031 |

| Absorbance at 620 | 0.41 ± 0.001 | 0.23 ± 0.032 |

Values are the mean of three injections; the standard deviation values (±) are indicated; n.d. not detectable.

Comparation of selected volatile compounds concentration in wine produced in lab-, pilot-, and industrial scale

The influence of the mixed starter H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae, used to produce Negroamaro wine in laboratory-, pilot-, and industrial scale, on the organoleptic quality of wines was assessed by comparing the concentrations of specific volatile compounds, produced by yeast metabolism (Table 4). Each single analyzed compound, chosen between different esters, acids, alcohols, terpenes, and aldehydes, showed comparable concentration in the wines produced by the three vinifications.

Table 4.

Concentration of selected volatile compounds in wines obtained with the mixed starter H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae used in simultaneous inoculum.

| Lab-scale | Pilot-scale | Industrial-scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | H1+S | Control | H1+S | Control | H1+S | |

| ESTERS | ||||||

| Isoamyl acetate | 369.35 | 2330.00 | 2234.67 | 2239.18 | 312.05 | 2596.76 |

| Ethyl hexanoate | 434.51 | 510.00 | 510.49 | 560.85 | 433.73 | 547.57 |

| Ethyl octanoate | 371.69 | 604.91 | 406.42 | 573.12 | 476.00 | 661.15 |

| 3-Hydroxy-ethyl butanoate | 53.79 | 69.78 | 52.23 | 65.35 | 51.41 | 67.74 |

| Ethyl decanoate | 183.24 | 230.00 | 188.19 | 252.18 | 234.87 | 229.38 |

| Phenylethyl acetate | 413.57 | 620.00 | 516.66 | 695.84 | 493.73 | 649.92 |

| Ethyl acetate (mg/L) | 42.11 | 84.78 | 22.07 | 92.04 | 25.05 | 87.04 |

| ALCOHOLS | ||||||

| Isoamyl alcohols | 547.85 | 750.00 | 554.01 | 767.61 | 680.33 | 801.87 |

| Phenylethylalcohol | 11,480.03 | 11,994.45 | 13,760.43 | 12,962.32 | 10,555.51 | 11,716.07 |

| ACIDS | ||||||

| Hexanoic acid | 2088.15 | 2246.68 | 2159.34 | 2366.45 | 2200.32 | 2246.68 |

| Octanoic acid | 3869.21 | 4574.65 | 3921.89 | 4716.22 | 3722.84 | 4574.65 |

| TERPENS | ||||||

| Terpineol | 54.13 | 66.50 | 50.40 | 72.80 | 57.15 | 68.80 |

| KETONS/ALDEHYDES | ||||||

| Acetoin (mg/L) | 4.11 | 11.24 | 7.65 | 11.85 | 6.05 | 11.34 |

| Acetaldehyde (mg/L) | 5.04 | 25.05 | 6.05 | 28.00 | 5.11 | 24.11 |

The pure culture of S. cerevisiae was used as control.

When compared to the wines produced by using the S. cerevisiae as starter, the three wines produced by inoculation of the mixed starter showed an increment of acetate esters (ethyl acetate, isoamyl acetate, and phenylacetate) and fatty acids esters (ethyl hexanoate, ethyl octanoate, and ethyl decanoate). Esters is one of the large groups of volatiles found in wines. These compounds are important in young wine aroma and are among key compounds in the fruity flavors of wines (Rapp and Mandery, 1986). Ethyl acetate, in particular, adds complexity to the aroma of wine, with fruity notes at concentrations lower than 150 mg/L, while at higher concentrations it can donate a sour, vinegary off-odor. Its higher concentration was found in H1+S industrial scale (87.04 mg/L).

Regarding alcohols, in particular isoamylalcohols and 2-phenylethanol were determined in the analyzed wines and they resulted to be quantitatively the most representative compounds in this group, showing a higher concentrations of these molecules when compared to the wines produced by the S. cerevisiae starter. Isoamylalcohols can have both positive and negative impacts on wine aroma. In fact alcohols concentrations exceeding 400 mg/L can have a detrimental effect (Rapp and Versini, 1991; Romano et al., 1997), whereas lower concentrations impart positive fruity characters (Lambrechts and Pretorius, 2000; Saurina, 2010). In our sample the concentrations detected were below this threshold. However, 2-phenylethanol was the second most abundant alcohol at concentrations higher than its threshold (10 mg/L), contributing with fine rose's notes to wine aroma.

Discussion

The utilization of non-Saccharomyces starters together with Saccharomyces cerevisiae in grape must fermentations has been investigated by Zironi and coworkers since 1993. The addition of yeasts belonging to non-Saccharomyces species as part of formulations of mixed starters, together with S. cerevisiae, has recently been indicated as a way to mimic the biotechnological potential associated with spontaneous fermentations to improve the quality of the wine (Rojas et al., 2001; Romano et al., 2003; Ciani et al., 2010).

Several non-Saccharomyces species, such as H. uvarum, Zygosaccharomyces bailii, Lachancea thermotolerans, Candida cantarelli, and C. zemplinina have been studied thus far in mixed fermentations with the scope of adding peculiar features to the wine (Toro and Vazquez, 2002; Ciani et al., 2006; Comitini et al., 2011; Suzzi et al., 2012; Gobbi et al., 2013; Garavaglia et al., 2015). In fact, a current trend in the wine market is to develop unique products, thus the mixed starter could be a good approach to give a special flavor and improve the quality of wines from both the organoleptic and microbiological point of view (Zironi et al., 1993; Mingorance-Cazorla et al., 2003; Capozzi et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2015; Masneuf-Pomarede et al., 2016). Moreover, in the contexst of the oenological production of Southern Italy (and other similar climates) denoted by high alcohol content and high total acidity, the preliminary utilization of a non-Saccharomyces starter (fructophylic and able to produce low amounts of acetic acid), might be an interesting approach in order to consume sugars in the early stage of fermentation, thus reducing the impact of osmotic stress for the S. cerevisiae starter (Rantsiou et al., 2012; Tofalo et al., 2012).

In the present investigation, we evaluated the fermentation performance of a culture of non-Saccharomyces yeasts belonging to the oenological species H. uvarum in micro-fermentation and, thereafter, in fermentations on pilot and industrial scale, conducted in mixed fermentations with yeasts belonging the species S. cerevisiae. These two different cultures were inoculated simultaneously or sequentially and the fermentation dynamics were studied in both fermentations. From the results of this series of tests, we obtained useful information on the kinetics of growth and fermentation activity, supported by analytical data of fermented musts and final wines.

In micro-fermentation trials, the presence of S. cerevisiae stimulated the persistence of the non-Saccharomyces strains during the fermentation process, in accordance with previous studies (Ciani et al., 2006; Mendoza et al., 2007; Mendoza and Farías, 2010), and this effect was more relevant in the sequential fermentations. Indeed, the three H. uvarum strains stayed viable, at significant high concentration levels of about 104–106 CFU/mL until the end of the fermentation even with an alcohol content of about 12% (v/v). On the other hand, in the simultaneous inoculation, the presence of the non-Saccharomyces strains since the early stages of fermentation seems to affect the cell growth and biomass production of S. cerevisiae probably due to the competition for nutrients (Mendoza et al., 2007; Domizio et al., 2011; Suzzi et al., 2012). However, the interactions between the two species during grape must/wine fermentation should be further studied and deepened. In fact, the knowledge about the metabolic interactions between S. cerevisiae and non-Saccharomyces strains in winemaking is still limited (Wang et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the fermentation rates of the mixed fermentation were comparable to that of the S. cerevisiae pure culture. Regardless the biomass production or fermentation rates, all the mixed cultures reached the completion but produced lower concentrations of ethanol than the pure culture of S. cerevisiae in accordance with previous studies (Mendoza and Farías, 2010; Mendoza et al., 2011).

The fermentations on a laboratory scale carried on regularly and the analysis of the corresponding fermented musts have not revealed the presence of compounds with possible negative impact to a level that will exceed the threshold of sensory perception. On the contrary, wines obtained with the association H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae showed some interesting characters. In fact, the evidence obtained during this investigation confirm previous data indicating that the combination and the interaction between the starter cultures of S. cerevisiae and non-Saccharomyces species has led to a reduction of acetic acid, even at concentrations lower than those produced by the pure culture of S. cerevisiae (Ciani et al., 2006; Mendoza and Farías, 2010; Domizio et al., 2011).

Several studies on the use of associated S. cerevisiae and non-Saccharomyces yeasts have highlighted many of the positive effects produced in these mixed fermentations such as the increasing in isoamyl acetate and 2-phenyl acetate (Moreira et al., 2008; Andorrà et al., 2010) or glycerol (Ciani and Ferraro, 1996) content in wine. Indeed, in the trial H1+S_sm, it was possible to note an increase of glycerol as well as of some volatile compounds, such as esters and aliphatic higher alcohols, as previously reported (Garde-Cerdán and Ancín-Azpilicueta, 2006). However, the impact of glycerol on the wine quality is still under discussion (Marchal et al., 2011).

These results were further confirmed in a pilot-scale vinification using a H. uvarum strain (ITEM 8795) in combination with S. cerevisiae ITEM 6920. The wines produced using two different strategies of inoculation (simultaneous and sequential) of the H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae starter were compared with that obtained after inoculation of a pure culture of S. cerevisiae, mainly focusing on their aromatic profile. It was also observed a different use of sugars in the tests in co-inoculation with H. uvarum. In fact, this fructophilic yeast interacts positively with the strain of S. cerevisiae, which is glucophilic, with the result of a more rapid utilization of the sugars (Ciani and Fatichenti, 1999). H. uvarum ITEM 8795, in simultaneous and sequential cultures, showed the maximal cell concentration after 2 days and then they die but remained in countable numbers until the end of the fermentation. This behavior of the apiculate yeast is in agreement with data reported in literature, which indicate that non-Saccharomyces yeasts dominate during the first 3–4 days of fermentations up to an ethanol concentration of about 4–7% (v/v) and then they start the phase of death (Fleet and Heard, 1993; Fleet, 2003). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that non-Saccharomyces yeasts kept their viability for longer period in composite cultures with S. cerevisiae (Ciani et al., 2006; Mendoza et al., 2007). The estimation of some of the principal volatile compounds confirmed that the H. uvarum ITEM 8975 did not form high amounts of ethyl acetate in mixed cultures (De Benedictis et al., 2011). However, in mixed cultures, the concentration of ethyl acetate produced are likely to contribute to the fruity notes and add to the general complexity to the produced wine (Ciani et al., 2006). The H. uvarum ITEM 8975 confirmed to be an acetoin low-producer even in multi-starter fermentations, it being this compound probably also consumed by the vigorously fermenting S. cerevisiae starter strain (Romano et al., 2003).

The amounts of acetaldehyde, a relevant secondary product of fermentation (Romano et al., 1997), did not appear to be negatively influenced by mixed cultures of H. uvarum, with a behavior similar to that described by Ciani et al. (2006) during the studies of lab-scale H. uvarum multi-started fermentations.

Ethyl esters concentrations are influenced by yeast strain, fermentation temperature, aeration degree and sugar content. Both ethyl esters and acetate esters have a key importance in the whole wine aroma impressing a positive contribution by distinct sensory notes: sweet-fruity, grape-like odor, sweet-balsamic (Rapp, 1990; Swiegers and Pretorius, 2005). Indeed, wine yeasts such as Hanseniaspora spp. in mixed fermentations with S. cerevisiae, have improved the formation of esters with a positive sensorial impact, as well as the reduction of volatile acidity production (Rojas et al., 2003; Moreira et al., 2005; Medina et al., 2013). Chemical analysis of the wines produced using the mixed cultures H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae clearly differ from wine produced with the solo S. cerevisiae. Both mixed fermentations led to a higher content of esters such as 2-phenylethyl acetate, which is in agreement with previous studies conducted with H. vineae (Viana et al., 2011; Medina et al., 2013) and H. guilliermondii (Rojas et al., 2003; Moreira et al., 2011). This compound contributes to the rose, honey, fruity and flower aromas of wines (Swiegers et al., 2005). Likewise, 2-phenylethanol contributes with a floral (rose) aroma in the final wine (Swiegers et al., 2005) though, an excess in higher alcohols concentrations in wine would bring a strong, pungent smell and taste (Moreira et al., 2011). In our study, the use of the apiculate yeast H. uvarum in mixed starter culture with S. cerevisiae decreased the total higher alcohol content and resulted in a concentration of 2-phenylethyl alcohol just above its sensory threshold (Moreira et al., 2008; Medina et al., 2013). Mixed fermentations also resulted in decreases in isovaleric acid and increases in hexanoic, octanoic acid and ethyl octanoate. Moreover, the presence of higher levels of decanoic acid and ethyl decanoate was correlated with greater rates of cell lysis, which could contribute to the tropical fruit aroma, texture and body of wines (Medina et al., 2013). On the basis of the above findings, we can say that co-inoculation represents an alternative approach in commercial winemaking and its success strongly depends on the selection of suitable yeast strains. In this study carried out at industrial level, the use of selected yeasts provides good results in terms of lack of wine alterations. The scale-up of mixed fermentation, for the first time, to an industrial level was the key step to validate the results obtained in the laboratory and in pilot-scale. The winemaking process has largely confirmed both the evolution of the cultures inoculated and the analytical characteristics of wines given by the strains of H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae used for the fermentation. The results obtained were supported by the fact that both inoculated strains were dominant on indigenous microflora and, thus, they have certainly conducted the fermentative process. The data achieved during the present investigation confirmed the concept that oenological non-Saccharomyces yeasts represent a resource of great value for the winemaking industry. Indeed, the obtained results indicated the H. uvarum strain ITEM 8795 can be used in association with S. cerevisiae starter cultures in the in the winemaking conditions typical of Southern Italy (Puglia) wine production. The here-described multi-starter fermentation was able to enhance the quality, improve the aromatic profile and reduce the effect of the undesired characters of the final Negroamaro wine.

Author contributions

All authors significantly contributed to this paper. FG and GS conceived and designed the experiments; MTr, MTu, and VC performed the experiments; FG, GS, MTr, MTu, GM, and VC analyzed the data; FG was responsible for manuscript preparation and submission; FG, GS, MTr, MTu, GM, and VC reviewed the paper.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the Apulian Region Project cod. QCBRAJ6 “Biotecnologie degli alimenti per l'innovazione e la competitività delle principali filiere regionali: estensione della conservabilità e aspetti funzionali—BIOTECA.” VC is supported by the Apulian Region in the framework of “FutureInResearch” program (practice code 9OJ4W81). MTr was partially supported by the Apulian Region in the framework of “Ritorno al futuro” program. The authors thank Mr. Giovanni Colella for the valuable technical help. The authors acknowledge Prof. J. Smith for proofreading and valuable linguistic advice.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00670

References

- Andorrà I., Berradre M., Rozès N., Mas A., Guillamón J. M., Esteve-Zarzoso B. (2010). Effect of pure and mixed cultures of the main wine yeast species on grape must fermentations. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 231, 215–224. 10.1007/s00217-010-1272-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleve G., Lezzi C., Chiriatti M. A., D'Ostuni I., Tristezza M., Di Venere D., et al. (2011). Selection of non-conventional yeasts and their use in immobilized form for the bioremediation of olive oil mill wastewaters. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 982–989. 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.09.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone S., Tufariello M., Siciliano P. (2013). Analytical characterization of Negroamaro red wines by “Aroma Wheels.” Food Chem. 141, 2906–2915. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi V., Garofalo C., Chiriatti M. A., Grieco F., Spano G. (2015). Microbial terroir and food innovation: the case of yeast biodiversity in wine. Microbiol. Res. 181, 75–83. 10.1016/j.micres.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi V., Spano G. (2011). Food microbial biodiversity and “Microbes of Protected Origin.” Front. Microbiol. 2:237 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caridi A., Ramondino D. (1999). Biodiversità fenotipica in ceppi di Hanseniaspora di origine enologica. Enotecnico 45, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ciani M., Beco L., Comitini F. (2006). Fermentation behavior and metabolic interactions of multistarter wine yeast fermentations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 108, 239–245. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani M., Comitini F., Mannazzu I., Domizio P. (2010). Controlled mixed culture fermentation: a new perspective on the use of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in winemaking. FEMS Yeast Res. 10, 123–133. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani M., Fatichenti F. (1999). Selective sugar consumption by apiculate yeasts. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28, 203–206. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00505.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani M., Ferraro L. (1996). Enhanced glycerol content in wines made with immobilized Candida stellata cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 128–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani M., Maccarelli F. (1998), Enological properties of non-Saccharomyces yeasts associated with wine-making. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 14, 199–203. 10.1023/A:1008825928354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comitini F., Gobbi M., Domizio P., Romani C., Lencioni L., Mannazzu I., et al. (2011). Selected non-Saccharomyces wine yeasts in controlled multistarter fermentations with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Microbiol. 28, 873–882. 10.1016/j.fm.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Benedictis M., Bleve G., Grieco F., Tristezza M., Tufariello M., Grieco F. (2011), An optimized procedure for the enological selection of non-Saccharomyces starter cultures. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 99, 189–200. 10.1007/s10482-010-9475-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domizio P., Lencioni L., Ciani M., Di Blasi S., Pontremolesi C., Sabatelli M. P. (2007). Spontaneous and inoculated yeast population dynamics and their effect on organoleptic characters of Vinsanto wine under different process conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 115, 281–289. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domizio P., Romani C., Lencioni L., Comitini F., Gobbi M., Mannazzu I., et al. (2011). Outlining a future for non-Saccharomyces yeasts: selection of putative spoilage wine strains to be used in association with Saccharomyces cerevisiae for grape juice fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 147, 170–180. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erten H. (2002). Relations between elevated temperatures and fermentation behaviour of Kloeckera apiculata and Saccharomyces cerevisiae associated with winemaking in mixed cultures. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18, 373–378. 10.1023/A:1015221406411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etievant P. X. (1991). Wine, in Volatile Compounds of Food and Beverages, ed Maarse H. (New York, NY: Dekker; ), 483–546. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira V., Lopez R., Cacho J. F. (2000). Quantitative determination of the odorants of young red wines from different grape varieties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 80, 1659–1667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet G. H. (2003). Yeast interactions and wine flavor. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 86, 11–22. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00245-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet G. H. (2008). Wine yeast for the future. FEMS Yeast Res. 8, 979–995. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet G. H., Heard G. M. (1993). Yeasts: growth during fermentation in Wine Microbiology and Biotechnology, ed Fleet G. H. (Philadelphia, PA: Harwood; ), 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Garavaglia J., de Souza Schneider R. D. C., Mendes S. D. C., Welke J. E., Zini C. A., Caramão E. B., et al. (2015). Evaluation of Zygosaccharomyces bailii BCV 08 as a co-starter in wine fermentation for the improvement of ethyl esters production. Microbiol. Res. 173, 59–65. 10.1016/j.micres.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garde-Cerdán T., Ancín-Azpilicueta C. (2006). Contribution of wild yeasts to the formation of volatile compounds in inoculated wine fermentations. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 222, 15–25. 10.1007/s00217-005-0029-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo C., El Khoury M., Lucas P., Bely M., Russo P., Spano G., et al. (2015). Autochthonous starter cultures and indigenous grape variety for regional wine production. J. Appl. Microbiol. 118, 1395–1408. 10.1111/jam.12789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil M., Cabellos J. M., Arroyo T., Prodanov M. (2006). Characterization of the volatile fraction of young wines from the Denomination of Origin “Vinos de Madrid” (Spain). Anal. Chim. Acta 563, 145–153. 10.1016/j.aca.2005.11.060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi M., Comitini F., Domizio P., Romani C., Lencioni L., Mannazzu I., et al. (2013). Lachancea thermotolerans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in simultaneous and sequential co-fermentation: a strategy to enhance acidity and improve the overall quality of wine. Food Microbiol. 33, 271–281. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Mínguez M. J., Cacho J. F., Ferreira V., Vicario I. M., Heredia F. J. (2007). Volatile components of Zalema white wines. Food Chem. 100, 1464–1473. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.11.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco F., Tristezza M., Vetrano C., Bleve G., Panico E., Grieco F., et al. (2011). Exploitation of autochthonous micro-organism potential to enhance the quality of Apulian wines. Ann. Microbiol. 61, 67–73. 10.1007/s13213-010-0091-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guth H. (1997). Identification of character impact odorants of different white wine varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45, 3022–3026. 10.1021/jf9608433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Ø., Harper D. A. T., Ryan P. D. (2001). PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Heard G. M., Fleet G. H. (1985). Growth of natural yeast flora during the fermentation of inoculated wines. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50, 727–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C. J., Fourie I., van Vuuren H. J. J. (1988). Occurrence and detection of killer yeasts on Chenin Blanc grapes and grape skins. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 9, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly N. P., Augustyn O. P. H., Pretorius I. S. (2006). The role and use of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in wine production. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 27, 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts M. G., Pretorius I. S. (2000). Yeast and its importance to wine aroma. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 21, 97–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Huang D., Lee P. R., Liu S.-Q. (2015). Assessment of volatile and non-volatile compounds in durian wines fermented with four commercial non-Saccharomyces yeasts. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96, 1511–1521. 10.1002/jsfa.7253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallouchos A., Skandamis P., Loukatos P., Komaitis M., Koutinas A., Kanellaki M. (2003). Volatile compounds of wines produced by cells immobilized on grape skins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 3060–3066. 10.1021/jf026177p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal A., Marullo P., Moine V., Dubourdieu D. (2011). Influence of yeast macromolecules on sweetness in dry wines: role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Hsp12. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 2004–2010. 10.1021/jf103710x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masneuf-Pomarede I., Bely M., Marullo P., Albertin W. (2016). The genetics of non-conventional wine yeasts: current knowledge and future challenges. Front. Microbiol. 6:1563. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina K., Boido E., Fariña L., Gioia O., Gomez M. E., Barquet M., et al. (2013). Increased flavour diversity of Chardonnay wines by spontaneous fermentation and co-fermentation with Hanseniaspora vineae. Food Chem. 141, 2513–2521. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza L., Farías M. E. (2010). Improvement of wine organoleptic characteristics by non-Saccharomyces yeasts. Curr. Res. Technol. Ed. Top. Appl. Microbiol. Microb. Biotechnol. 2, 908–919. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza L. M., Manca de Nadra M. C., Farias M. F. (2007). Kinetics and metabolic behavior of a composite culture of Kloeckera apiculata and Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine related strains. Biotechnol. Lett. 29, 1057–1063. 10.1007/s10529-007-9355-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza L. M., Merín M. G., Morata V. I., Farías M. E. (2011). Characterization of wines produced by mixed culture of autochthonous yeasts and Oenococcus oeni from the northwest region of Argentina. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38, 1777–1785. 10.1007/s10295-011-0964-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingorance-Cazorla L., Clemente-Jiménez J. M., Martınez-Rodrıguez S., Las Heras-Vazquez F. J., Rodrıguez-Vico F. (2003). Contribution of different natural yeasts to the aroma of two alcoholic beverages. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19, 297–304. 10.1023/A:1023662409828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira N., Mendes F., de Pinho P. G., Hogg T., Vasconcelos I. (2008). Heavy sulphur compounds, higher alcohols and esters production profile of Hanseniaspora uvarum and Hanseniaspora guilliermondii grown as pure and mixed cultures in grape must. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 124, 231–238. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira N., Mendes F., Hogg T., Vasconcelos I. (2005). Alcohols, esters and heavy sulphur compounds production by pure and mixed cultures of apiculate wine yeasts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 103, 285–294. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira N., Pina C., Mendes F., Couto J. A., Hogg T., Vasconcelos I. (2011). Volatile compounds contribution of Hanseniaspora guilliermondii and Hanseniaspora uvarum during red wine vinifications. Food Control. 22, 662–667. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.07.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pallmann C., Brown J., Olineka T., Cocolin L., Mills D., Bisson L. (2001). Use of WL medium to profile native flora fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vit. 52, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Coello M. S., Briones Pérez A. I., Ubeda Iranzo J. F., Martin Alvarez P. J. (1999). Characteristics of wines fermented with different Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains isolated from the La Mancha region. Food Microbiol. 16, 563–573. 10.1006/fmic.1999.0272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rantsiou K., Dolci P., Giacosa S., Torchio F., Tofalo R., Torriani S., et al. (2012). Candida zemplinina can reduce acetic acid produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae in sweet wine fermentations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 1987–1994. 10.1128/AEM.06768-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp A. (1990). Natural flavours of wine: correlation between instrumental analysis and sensory perception. J. Anal. Chem. 337, 777–785. 10.1007/BF00322252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp A., Mandery H. (1986). Wine aroma. Experientia 42, 873–883. 10.1007/BF0194176425903098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp A., Versini G. (1991). Influence of nitrogen compounds in grapes on aroma compounds in wine, in Proceedings of the International Symposium on Nitrogen in Grapes and Wine, Seattle, USA (Davis, CA: American Society of Enology and Viticulture; ), 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha S. M., Rodrigues F., Coutinho P., Delgadillo I., Coimbra M. A. (2004). Volatile composition of Baga red wine assessment of the identification of the would-be impact odourants. Anal. Chim. Acta 513, 257–262. 10.1016/j.aca.2003.10.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas V., Gil J. V., Pinaga F., Manzanares P. (2001). Studies on acetate ester production by non- Saccharomyces wine yeasts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 70, 283–289. 10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00552-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas V., Gil J. V., Piñaga F., Manzanares P. (2003). Acetate ester formation in wine by mixed cultures in laboratories fermentations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 86, 181–188. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00255-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano P., Fiore C., Paraggio M., Caruso M., Capece A. (2003). Function of yeast species and strains in wine flavour. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 86, 169–180. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00290-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano P., Suzzi G., Comi G., Zironi R. (1992). Higher alcohol and acetic acid production by apiculate wine yeasts. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 73, 126–130. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01698.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romano P., Suzzi G., Comi G., Zironi R., Maifreni M. (1997). Glycerol and other fermentation products of apiculate wine yeasts. J. Appl. Microbiol. 82, 615–618. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1997.tb02870.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurina J. (2010). Characterization of wines using compositional profiles and chemometric. Trends Anal. Chem. 29, 234–245. 10.1016/j.trac.2009.11.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spano G., Russo P., Lonvaud-Funel A., Lucas P., Alexandre H., Grandvalet C., et al. (2010). Biogenic amines in fermented foods. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64(suppl. 3), S95–S100. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Lepe J. A., Morata A. (2012). New trends in yeast selection for winemeking. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 23, 39–50. 10.1016/j.tifs.2011.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suzzi G., Schirone M., Sergi M., Marianella R. M., Fasoli G., Aguzzi, et al. (2012). Multistarter from organic viticulture for red wine Montepulciano d'Abruzzo production. Front. Microbiol 3:135. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiegers J. H., Bartowsky E. J., Henschke P. A., Pretorius I. S. (2005). Yeast and bacterial modulation of wine aroma and flavour. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 11, 139–173. 10.1111/j.1755-0238.2005.tb00285.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swiegers J. H., Pretorius I. S. (2005). Yeast modulation of wine flavor. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 57, 131–175. 10.1016/S0065-2164(05)57005-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofalo R., Schirone M., Torriani S., Rantsiou K., Cocolin L., Perpetuini G., et al. (2012). Diversity of Candida zemplinina strains from grapes and Italian wines. Food Microbiol. 29, 18–26. 10.1016/j.fm.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro M. E., Vazquez F. (2002). Fermentation behaviour of controlled mixed and sequential cultures of Candida cantarellii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine yeasts. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18, 347–354. 10.1023/A:1015242818473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tristezza M., Gerardi C., Logrieco A., Grieco F. (2009). An optimized protocol for the production of interdelta markers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by using capillary electrophoresis. J. Microbiol. Meth. 78, 286–291. 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tristezza M., Vetrano C., Bleve G., Grieco F., Tufariello M., Quarta A., et al. (2012). Autochthonous fermentation starters for the industrial production of Negroamaro wines. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39, 81–92. 10.1007/s10295-011-1002-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tristezza M., Vetrano C., Bleve G., Spano G., Capozzi V., Logrieco A., et al. (2013). Biodiversity and safety aspects of yeast strains characterized from vineyards and spontaneous fermentations in the Apulia Region, Italy. Food Microbiol. 36, 335–342. 10.1016/j.fm.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufariello M., Capone S., Siciliano P. (2012). Volatile components of Negroamaro red wines produced in Apulian Salento area. Food Chem. 132, 2155–2164. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viana F., Belloch C., Vallés S., Manzanares P. (2011). Monitoring a mixed starter of Hanseniaspora vineae–Saccharomyces cerevisiae in natural must: impact on 2-phenylethyl acetate production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 151, 235–240. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana F., Gil J. V., Genovés S., Vallés S., Manzanares P. (2008). Rational selection of non-Saccharomyces wine yeast for mixed starters based on ester formation and enological traits. Food Microbiol. 25, 778–785. 10.1016/j.fm.2008.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Mas A., Esteve-Zarzoso B. (2015). Interaction between Hanseniaspora uvarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae during alcoholic fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 206, 67–74. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zironi R., Romano P., Suzzi G., Battistuta F., Comi G. (1993). Volatile metabolites produced in wine by mixed and sequential cultures of Hanseniaspora guilliermondii or Kloeckera apiculata and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Lett. 15, 235–238. 10.1007/BF0012831117440687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.