Abstract

Previous work has established that binding of the 11-5.2 anti-I-Ak mAb, which recognizes the Ia.2 epitope on I-Ak class II molecules, elicits MHC class II signaling, whereas binding of two other anti-I-Ak mAb that recognize the Ia.17 epitope fail to elicit signaling. Using a biochemical approach, we establish that the Ia.2 epitope recognized by the widely used 11-5.2 mAb defines a subset of cell surface I-Ak molecules predominantly found within membrane lipid rafts. Functional studies demonstrate that the Ia.2 bearing subset of I-Ak class II molecules is critically necessary for effective B cell–T cell interactions especially at low antigen doses, a finding consistent with published studies on the role of raft-resident class II molecules in CD4 T cell activation. Interestingly, B cells expressing recombinant I-Ak class II molecules possessing a β chain-tethered HEL peptide lack the Ia.2 epitope and fail to partition into lipid rafts. Moreover, cells expressing Ia.2 negative tethered peptide-class II molecules are severely impaired in their ability to present both tethered peptide or peptide derived from exogenous antigen to CD4 T cells. These results establish the Ia.2 epitope as defining a lipid raft-resident MHC class II confomer vital to the initiation of MHC class II restricted B cell–T cell interactions.

Introduction

MHC class II-restricted cognate interactions between antigen specific B cells and CD4 helper T cells are necessary for initiation and full development of a humoral immune response. It has long been appreciated that MHC class II molecules can adopt multiple conformations with distinct activities. Possibly the most well known example is SDS-stable vs. SDS-sensitive peptide-class II complexes (1). Another example is Type A vs. Type B peptide-class II complexes that were identified and characterized by Unanue and colleagues [reviewed in (2)]. Here, the structural difference between Type A and Type B peptide-class II complexes is unknown, so the complexes are functionally defined based on their ability to be recognized by Type A or Type B reactive T cells. Nevertheless, studies have established that Type A peptide-class II complexes are formed in late endocytic compartments under the influence of the class II chaperone HLA-DM/H-2M (DM3), whereas Type B complexes are formed in early endocytic compartments (which lack abundant DM) and are actually destroyed upon interaction with the DM chaperone. Due to the DM dependence of Type A complexes, the distinction between Types A and B are most likely centered on differences in bound peptides.

Early serological studies of H-2 Ia determinants (now I-A and I-E) revealed the presence of multiple determinants restricted to the k haplotype such as Ia.2, Ia.19 and Ia.17 (3). Later, mAb were used to confirm Ia.2 and Ia.19 as private epitopes restricted to I-Ak class II molecules (3, 4). In 1981 Pierres and colleagues reported that the binding of multiple anti-Ia.2 mAb augments subsequent binding of other anti-I-Ak mAb, an effect which the authors speculate is due to an anti-Ia.2-induced shift in the structure of the I-Ak molecule (5). Later, the binding of anti-Ia.2 mAb such as 11-5.2 were found to be highly dependent on residues arginine-57 and glutamine-75 of the I-Ak α chain (6, 7), residues that are physically located close to the peptide-binding groove of the molecule. Follow up studies revealed that expression of an epitope closely related to Ia.2 (Ia.19) was dependent upon the presence of the appropriate MHC class II β chain, further supporting the idea that Ia.2 and Ia.19 may be conformational epitopes (8). Subsequently, in 1992 Cosson and Bonifacino demonstrated that mutation of residues within the transmembrane domain of the I-Ak α and β chain polypeptides results in loss of the Ia.2 epitope without loss of I-Ak expression (9). Taken together these results suggest that the Ia.2 epitope is a conformational epitope.

Most recently, studies of MHC class II signaling in resting B cells have revealed one such example of a functional distinction between I-Ak class II molecules based on conformational epitopes (10). Specifically, binding of the anti-Ia.2 mAb 11-5.2 was found to elicit Src family kinase-dependent intracellular Ca2+ signaling and B cell activation, whereas binding of multiple anti-Ia.17 mAbs failed to elicit such signaling. These data support the hypothesis that MHC class II molecules with a particular conformation (Ia.2) may represent a functionally distinct population. This current report extends those findings and establishes that the Ia.2 epitope bound by the 11-5.2 mAb defines a subset of lipid raft resident MHC class II conformers central to effective activation of CD4 T cells. When taken in context with the previous literature on the Ia.2 epitope, these results establish that the Ia.2 epitope defines a subset of MHC class II conformers localized to lipid rafts that are central to both effective antigen presentation to CD4 T cells as well as MHC class II-mediated B cell activation.

Materials and Methods

Cells

TA3 B cells (a hybridoma derived by fusion of the Balb/c-derived A20 lymphoma with splenocytes from an H-2kmouse and expressing wild type I-Ak class II) were grown as previously reported (11). HEL46-61–I-Ak-specific h4Ly50.5 (Ly50) T cells (a gift of Dr. Bill Wade, Dartmouth) were grown in DME 10% FBS, 1mM Na+ pyruvate, 2mM L-glutamine, and 50 μM 2-ME. HEK293T cells stably transfected to express CIITA (a gift from Dr. Karen Duus, Albany Medical College) were grown in DME 10% FBS, 1mM Na+ pyruvate, 2mM L-glutamine, 50 μM 2-ME and 5mM L-histidinol. IIA1.6 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown in αMEM 5% FBS and 25 μM 2-ME. Splenic B cells from I-Ak-expressing B10.Br and MD4.B10.Br mice (expressing a transgenic HEL specific IgMa BCR) were prepared as previously reported (12, 13). Animal protocols have been reviewed and approved by appropriate institutional review committees.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were stained with 10-3.6-PE (BioLegend #109908, San Diego, CA) and 11-5.2-FITC (BD Pharmingen #553536, San Diego, CA) in HBSS 0.1% BSA, with a final wash containing 0.1 μg/ml propidium iodide (splenocytes were also stained with anti-CD19-PE-Cy7, BD Pharmingen, but no propidium iodide). Some samples were stained with Aw3.18 (14) followed by anti-muIgG1-FITC (BD Pharmingen #553443). Samples were analyzed either on a FACScan or FacsCanto (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Splenic B cells were analyzed by gating on CD19+ cells.

Class II Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (10), and lysates cleared with protein G sepharose (PGS, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Class II was immunoprecipitated (IP) with 11-5.2 (anti-Ia.2), 10-2.16 (anti-Ia.17), M5/114 (anti-I-Ab,d and I-Ek) plus PGS. Class II was IP from first round IP supernatants by the same approach. Washed IP were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and western blotted with rabbit anti-I-A (15) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Calbiochem #401353, San Diego, CA). Blots were developed with SuperSignal West Dura ECL substrate (Pierce Biotechnology), using Blue Sensitive film (Laboratory Product Sales, Rochester, NY). Similar results were obtained using rabbit anti-class II β chain cytoplasmic domain antibody.

Analysis of MHC Class II Lipid Raft Partitioning

Lipid raft partitioning of I-Ak molecules was determined using a variation of our published protocol (16, 17). 107 B cells were labeled with 11-5.2-btn (BD Pharmingen #553534), 10-3.6-btn (BioLegend #109902) or CTB-btn (Sigma #C9972) on ice, followed by streptavidin-HRP (15 min. on ice, followed by 5 min. at 37°C). Cells were washed and lysed in TNE 1% TX-100 at 108 viable cells/ml. Lysates were fractionated on a 5/32/37.5% sucrose step gradient using a TLS-55 rotor (4 hr at 48,000 rpm). HRP activity was measured via a colorometric assay (16, 17). Total class II was determined by SDS-PAGE and western blot of equal volumes of gradient fractions, as detailed above.

MHC Class II Internalization

Internalization of 11-5.2-btn, 10-3.6-btn and anti-IgMb-btn (BD Pharmingen #553515) was determined by flow cytometry as previously reported (16), using streptavidin-Alexa 488 (Invitrogen #532354) to detect surface mAb-btn. A similar approach was used to follow the internalization of 10-2.16, using anti-muIgG2b-FITC (BD Pharmingen) as a probe.

Analysis of B Cell-T Cell Conjugates

Formation of B cell–T cell conjugates was determined by a modification of our published protocol (13). Splenic B cells expressing Type I (BCR-generated) or Type II (fluid-phase generated) peptide-class II complexes were prepared as previously reported (13). B cells were labeled with anti-B220-PE (BD Pharmingen #553090). Ly50 T cells were labeled with anti-Thy1.2-FITC (BD Pharmingen #553014). Labeled B and T cells were mixed at a 1:4 ratio and co-sedimented by centrifugation for 3 min at 200 × g. After incubation for 20 min at 37°C, samples were resuspended, incubated an additional 5 min at 37°C (to allow dissociation of unstable conjugates) and the level of B cell–T cell conjugation determined by flow cytometry. Conjugate formation by non-HEL pulsed B cells was consistently < 5%. Anti-class II mAb were bound to B cells on ice before addition of T cells and were maintained throughout the remainder of the experiment.

Analysis of Ia.2 Epitope Expression by Transfection

Aαk and Aβk proteins were expressed from the pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1/Hygro vectors, respectively (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All mutagenesis was done using the QuikChange Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), and confirmed by sequencing. ΔCT constructs were generated by insertion of a stop codon following Aαk R202 and Aβk R221. The HEL tethered Aβk and AβkΔCT constructs contains HEL47-62 followed by an 8 amino acid glycine linker inserted between Aβk residues E4 and F7, similar to that done previously (18), resulting in the sequence: E4-G-TDGSTDYGILQINSRWGGGGGGGG-SA-F7. Transient transfection into HEK293T-CIITA cells was done using FuGene HD (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and 1μg of each construct at a 2:7 total DNA:FuGene ratio. Cells were analyzed 20–24 hours post-transfection. Stable transfection of IIA1.6 cells was generated by electroporation with a GenePulser (Biorad, Hercules, CA) at 350V/500μF using 10μg of each construct. Twenty-four hours after electroporation, cells were selected with 1.4 mg/ml G418 (Mediatech, Manasses, VA), and 1 mg/ml hygromycin B (Mediatech) until cloning. Integration of the Aαk and Aβk constructs and derivatives was verified by RT-PCR of isolated mRNA.

Antigen Presentation

Clones of IIA1.6 cells expressing AαkΔCT/AβkΔCT and AαkΔCT/HEL-AβkΔCT, along with TA3 cells were separately mixed with Ly50.5 T cells and doses of HEL from 0–100μM. Following 20–24 hours of incubation, supernatant was collected and IL-2 levels measured by Cytometric Bead Array (BD Biosciences).

Nycodenz Density Gradient Centrifugation

TA3 cells were homogenized with a ball bearing homogenizer (0.2504″ bore, 0.2493″ ball) and cellular vesicle fractionated by Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation as previously published (26). Fractionated vesicles were lysed in 0.1% TX-100 and IP with either 10-2.16 (anti-Ia.17) or 11-5.2 (anti-Ia.2) plus protein G sepharose. IP were analyzed for MHC class II by western blot as detailed in the main Methods section of the report.

Invariant Chain Association

TA3 cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and Ia.17+ or Ia.2+ I-Ak IP with 10-3.6 or 11-5.2 as detailed in the main Methods section of the report. Invariant chain was detected by western blot analysis of the IP with In-1 (anti-CD74, Pharmingen 555317) followed by Gt anti-Rt IgG2b-HRP (Thermo Scientific PA1-84710). Blots were developed with SuperSignal West Dura ECL substrate.

Results

The Ia.2 epitope marks a subset of I-Ak MHC class II molecules

Previous studies using resting B10.Br splenic B cells established that binding of the 11-5.2 anti-I-Ak mAb, which recognizes the Ia.2 epitope localized to Aαk (6, 7), elicits Src kinase-mediated intracellular Ca2+ signaling, whereas binding of the 10-2.16 or 10-3.6 anti-I-Ak mAb, which recognize the Ia.17 epitope localized to Aβk (19), fails to elicit such a response (10). To investigate the molecular mechanism behind this observation, the distribution of the Ia.2 and Ia.17 epitopes on the population of I-Ak class II molecules was determined.

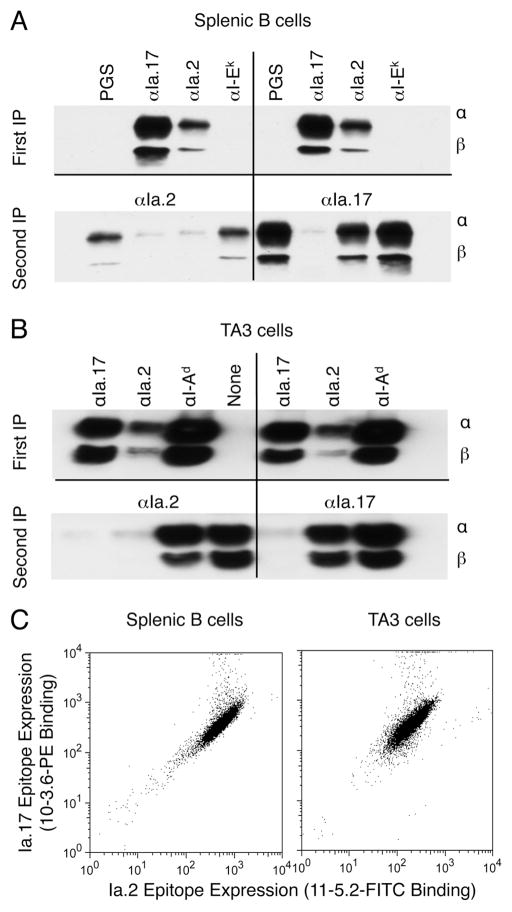

Sequential immunoprecipitation (IP) of lysates of B10.Br splenic B cells (Figure 1A) reveals that all I-Ak molecules that express the Ia.2 epitope also express the Ia.17 epitope, as no I-Ak can be detected in a second IP with anti-Ia.2 following an initial IP with anti-Ia.17. In contrast, some Ia.17+ I-Ak molecules lack the Ia.2 epitope as indicated by the ability of anti-Ia.17 to IP I-Ak class II molecules from samples previously cleared with anti-Ia.2 mAb. The finding that re-precipitation of these samples with anti-Ia.2 mAb does not bring down additional class II rules out the possibility that subsaturating amounts of anti-Ia.2 was used for the initial IP. Similar results were obtained with the I-Ak expressing TA3 B cell line (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1. The signaling-competent anti-Ia.2 monoclonal antibody 11-5.2 recognizes a subset of I-Ak class II molecules.

Panel A: B10.Br splenocyte lysates were immunoprecipitated (first IP) as indicated (PGS = protein G-sepharose only). Supernatants from the first IP were re-precipitated as indicted (second IP). IP were analyzed for class II by western blot with polyclonal anti-I-A antibody, which detects both class II α and β chains (15). Western blot analysis of supernatants from anti-Ia.17 IP revealed a lack of residual class II molecules, establishing that the Ia.17 epitope marks all cell surface I-Ak molecules. Shown are representative results from 1 of 3 independent experiments.

Panel B: TA3 B cell lysates were analyzed as described in panel A. Shown are representative results from 1 of 3 independent experiments.

Panel C: B10.Br splenic B cells or TA3 B cells were stained with 11-5.2–FITC and 10-3.6-PE. Splenic B cells were also stained with anti-CD19-PE-Cy7. Shown is the level of 11-5.2 and 10-3.6 staining for CD19+ splenic B cells and total TA3 B cells from 1 of 4 independent experiments.

To determine whether the Ia.2+/Ia.17+ vs. Ia.2−/Ia.17+ subsets of class II were expressed on different populations of B cells, both splenic B cells and TA3 cells were stained with anti-Ia.2-FITC and anti-Ia.17-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 1C). Both cell types stain uniformly positive for both Ia.2 and Ia.17, indicating that the Ia.2 epitope marks a subset of I-Ak class II molecules expressed by all B cells (Figure 2C). This finding is consistent with previous ELISA based analysis of the distribution of Ia.2 and Ia.17 epitopes on detergent-solubilized I-Ak (20), which lead the authors to suggest that the Ia.2 epitope is not present on all I-Ak molecules. Analysis of BCR activated of splenic B cells revealed that activation up-regulates the expression of both total (Ia.17+) and Ia.2+ class II to the same extent (Ia.17 up-regulation: 2.08 fold +/− 0.22, Ia.2 up-regulation: 2.10 fold +/− 0.06) and has no effect on the ability of the anti-Ia.2 mAb to elicit signaling (10). Thus, we have restricted the subsequent analysis of Ia.2+ class II to resting B cells and I-Ak bearing-B cell lines.

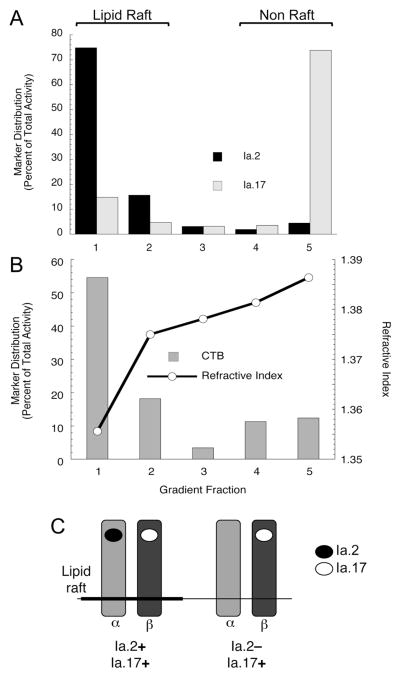

FIGURE 2. The Ia.2+ subset of I-Ak class II molecules exhibits heightened partitioning into plasma membrane lipid rafts.

Panel A: Biotinylated anti-Ia.2 or anti-Ia.17 mAb was bound to TA3 B cells, and then labeled with streptavidin-HRP. Cells were lysed in TNE 1% TX-100, lipid rafts were isolated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation, and the distribution of the HRP-tagged anti-class II mAb was determined via a colorometric assay (16, 17). Antibody distribution is reported as the percent of total activity detected in each fraction. Shown are representative results from 1 of 3 independent experiments. The average level of anti-Ia.2 in lipid rafts (fractions 1 and 2) was 86.1% ± 7.8% (1 S.D.). The average level of anti-Ia.17 in lipid rafts was 18.0% ± 4.7% (1 S.D.).

Panel B: Parallel samples of TA3 B cells were labeled with CTB-HRP and analyzed as in panel A. The refractive index reflects the density profile of the sucrose gradient. Shown are representative results from 1 of 3 independent experiments.

Panel C: Diagrammatic representation of the distribution of the Ia.2 and Ia.17 epitopes on the two subsets of I-Ak molecules. Black circle represents the Ia.2 epitope previously mapped to the I-Ak α chain (6, 7). White circle represents the Ia.17 epitope previously mapped to the I-Ak β chain (19).

The Ia.2 positive class II subset is enriched in lipid rafts

Previous studies have established a role for lipid rafts in MHC class II signaling in human monocytes (21) and class II transfected sarcoma cells (22). To determine if the previously reported signaling capacity of Ia.2+ I-Ak class II in B cells (10) is related to partitioning of this subset of class II molecules into lipid rafts, the raft localization of both the total (i.e., Ia.17+) and Ia.2+ populations of I-Ak class II molecules was determined (Figure 2A). Consistent with previous reports (23), only 15–20% of total (i.e. Ia.17+) cell surface I-Ak is present in plasma membrane lipid rafts. In contrast, almost 90% of Ia.2+ class II is found in plasma membrane lipid rafts, closely mirroring the distribution of cholera toxin B (CTB) which binds lipid raft-localized GM1 glycolipid molecules (Figure 2B).

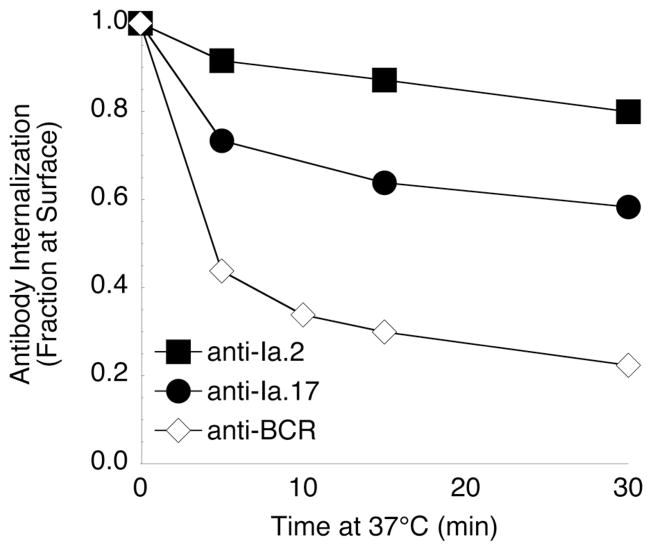

Previous analysis of B cell receptor (BCR) function has revealed that while lipid rafts play a critical role in BCR signaling, they represent inefficient internalization platforms (16, 17, 24). Therefore, to use an intact cell approach to further test the idea that the Ia.2 epitope marks a subset of lipid raft restricted class II molecules, the kinetics of class II-mediated internalization of the anti-Ia.2 and anti-Ia.17 mAb was determined. Consistent with the extensive lipid raft partitioning of Ia.2+ class II molecules (Figure 2), internalization of the anti-Ia.2 mAb is minimal and occurs with relatively slow kinetics (Figure 3), similar to the previously reported kinetics of lipid raft-mediated internalization of CTB (17) and GPI-linked BCR (24). In contrast, a significantly greater fraction of the anti-Ia.17 mAb (bound to all I-Ak molecules) is rapidly cleared from the cell surface, such that almost 40% of the bound anti-Ia.17 is internalized within 30 minutes (Figure 3). While it is possible that the lower level of anti-Ia.2 internalization is due in part to Ia.2+ class II recycling back to the cell surface, the similarity between the kinetics of anti-Ia.2 internalization and those of lipid raft bound CTB is fully consistent with the high level lipid raft partitioning of the subset of Ia.2+ class II molecules. Taken together the results presented in Figures 1 through 3 establish that while all I-Ak molecules bear the Ia.17 epitope, only a subset of signaling-competent lipid raft-localized I-Ak molecules possess the Ia.2 epitope recognized by the 11-5.2 mAb (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 3. Ia.2-bearing class II molecules exhibit a diminished antibody-elicited clearance from the cell surface.

Kinetics of internalization of class II-bound anti-Ia.2 and anti-Ia.17 mAb were analyzed as previously reported (16). αIgMb-btn internalization (n=2) was analyzed as a control. Shown is the average level of anti-Ia.2 and anti-Ia.17 mAb internalization (± 1 S.D., which is smaller than the icon) for 4 independent experiments (2 experiments of 11-5.2 vs. 10-2.16, and 2 experiments of 11-5.2 vs. 10-3.6). The difference in the endocytosis of the anti-Ia.2 and anti-Ia.17 mAb was confirmed by following the internalization of 11-5.2-biotin + streptavidin-HRP and 10-3.6-biotin + streptavidin-HRP using a colorometric assay that tracks both total and cell surface HRP (26) (data not shown).

Addition of a class II tethered peptide eliminates Ia.2 expression and class II lipid raft partitioning

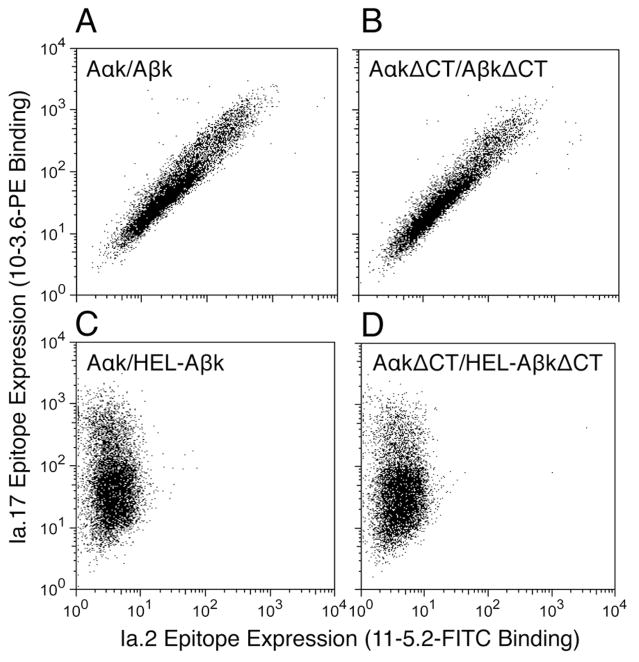

Since the cytoplasmic tail (CT) of class IIhas been reported to be important for lipid raft-dependent class II signaling in sarcoma cells (22), the role of these domains in the expression of the Ia.2 epitope was investigated. Either wild type or cytoplasmic tail deletion (ΔCT) mutants of Aαk and Aβk were expressed in CIITA expressing 293T cells and Ia.2 epitope expression monitored by staining with anti-Ia.2-FITC and anti-Ia.17-PE. As shown by the results presented in Figure 4 (panels A and B), deletion of the CT of both I-Ak chains has no impact on the level of Ia.2 epitope expression. Moreover, since 293T cells are not B cells (and do not express CD79), these results establish that formation of the Ia.2 epitope is not dependent upon association of class II and CD79 (25). However, this does not rule out the possibility that lipid raft-localized Ia.2+ class II molecules may exhibit a level of CD79 association distinct from that of total class II molecules.

FIGURE 4. Addition of a class II tethered peptide abolishes Ia.2 epitope expression.

293T embryonic fibroblasts stably expressing the class II transactivator CIITA (CIITA-293T) were transiently transfected with either (A) full length I-Ak (Aαk/Aβk), (B) cytoplasmic tail deletion I-Ak(A αk–ΔCT/Aβk–ΔCT), (C) full length I-Ak with a tethered peptide (Aαk/HEL-Aβk), (D) cytoplasmic tail deletion I-Ak (Aαk–ΔCT/HEL–Aβk–ΔCT). 24 hours after transfection, cells were stained with 11-5.2-FITC and 10-3.6-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are representative results from 1 of 5 independent experiments.

Another way that Ia.2 epitope acquisition could be controlled is during class II folding in the endoplasmic reticulum or peptide-loading compartment (i.e., MIIC). Since invariant chain (Ii) is critically involved in both of these aspects of class II biosynthesis, it is possible that Ii is controlling the formation of the Ia.2 epitope. To assess the impact of Ii association on Ia.2 epitope acquisition, a previously reported I-Ak construct with the immunodominant 47-62 peptide of hen egg lysozyme (HEL) tethered to the N terminus of Aβk via a flexible linker was expressed in CIITA transfected 293T cells (along with Aαk), and the cells analyzed by staining and flow cytometry. The tethered peptide should negate the need for CLIP-dependent Ii–class II association and impede Ii–chaperoned class II maturation (The tethered peptide was added to the ΔCT class II molecule to minimize class II internalization and subsequent cleavage and editing of the tethered peptide.). Interestingly, addition of the tethered HEL peptide (which can be detected bound to I-Ak at the cell surface, Figure 6A) abolishes Ia.2 epitope expression in both full-length (Figure 4C) as well as ΔCT class II molecules (Figure 4D). These results support the notion that Ii association supports generation of the Ia.2 epitope and demonstrates that there is essentially no contribution of the cytoplasmic domain of class II in Ia.2 epitope formation.

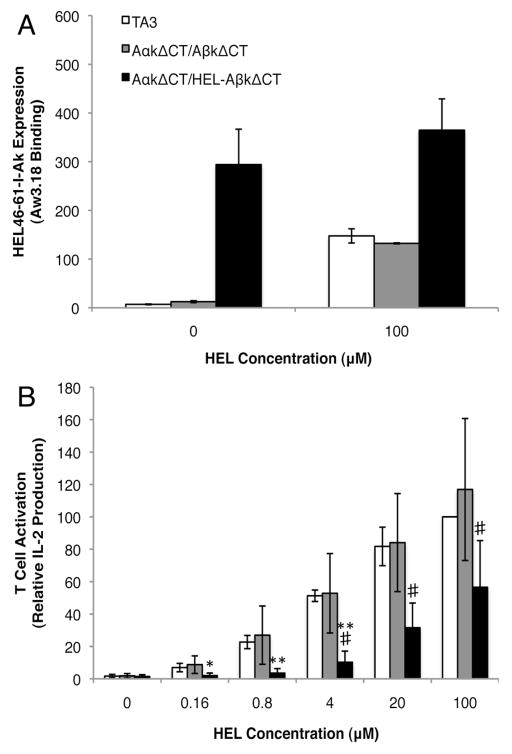

FIGURE 6. Ia.2-negative class II lacks the ability to stimulate CD4 T cells.

Panel A: IIA1.6 B cells stably expressing tailless I-Ak or HEL-tethered tailless I-Ak along with TA3 B cells were incubated overnight in media with or without 100 μM HEL protein. The cells were stained with the anti-HEL47-62-I-Ak specific Aw3.18 mAb and the level of mAb binding determined by flow cytometry. Shown is the average MFI of Aw3.18 staining ± 1 S.D. calculated from 3 independent experiments. Analysis of the Aw3.18 staining of HEL-pulsed vs. non HEL-pulsed IIA1.6 cells expressing HEL-tethered tailless I-Ak by a paired, 2-tailed Student’s t-test established a p value of 0.02.

Panel B: IIA1.6 B cells stably expressing tailless I-Ak or HEL-tethered tailless I-Ak along with TA3 B cells were incubated overnight with the I-Ak-HEL47-62-specific Ly50 T cell hybridoma and increasing doses of HEL protein. Supernatants were collected and IL-2 levels (as a readout of T cell activation) determined by cytometric bead array. Shown is the average IL-2 production (normalized to the amount of IL-2 produced by T cells activated by TA3 B cells pulsed with 100 μM HEL) ± 1 S.D. from 3 independent experiments. Statistics: HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT vs. I-Ak-ΔCT, # = p ≤ 0.05; HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT vs. TA3, * = p ≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.01.

Two ways by which Ii may control Ia.2 epitope acquisition are by controlling the intracellular trafficking of nascent class II molecules or by controlling MHC class II protein folding. To address the potential role of class II trafficking in acquisition of the Ia.2 epitope, DM+ MIIC antigen processing compartments were isolated from TA3 B cells by Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation (26) and the Ia.2 status of the MIIC localized I-Ak determined by IP/western blot (Supplementary Figure 1). The results establish the presence of Ia.2+ class II in DM+ MIIC, demonstrating that Ia.2 forms early in the biosynthetic pathway. Since previous work by Unanue and colleagues has shown that DM essentially prevents the formation of Type B peptide-class II complexes (2), these results also establish that Ia.2+ class II molecules are not equivalent to Type B complexes as defined by Unanue and colleagues.

To further investigate the potential role of Ii in Ia.2 epitope formation, the association of Ii with both total (Ia.17+) and Ia.2+ class II was determined by IP and western blotting (Supplementary Figure 2). Consistent with the MIIC localization of some Ia.2+ class II, Ii was found associated with both Ia.17+ and Ia.2+ class II. Moreover, Ii p31 is the predominant form of Ii associated with both Ia.17+ and Ia.2+ class II. Consistent with the apparently identical Ii association and intracellular trafficking of both total and Ia.2+ nascent class II, western blot analysis of anti-Ia.17 and anti-Ia.2 IP also revealed the equivalent relative level of SDS-stable αβ dimers (1) in both samples (data not shown). Taken together, these results are consistent with formation of the Ia.2 epitope early in the biosynthetic pathway, and indicate that if Ii directly controls acquisition of the Ia.2 epitope, it must be occurring by a mechanism other than a selective association of class II with the Ii p31 or p41 isoform. This idea is currently under investigation.

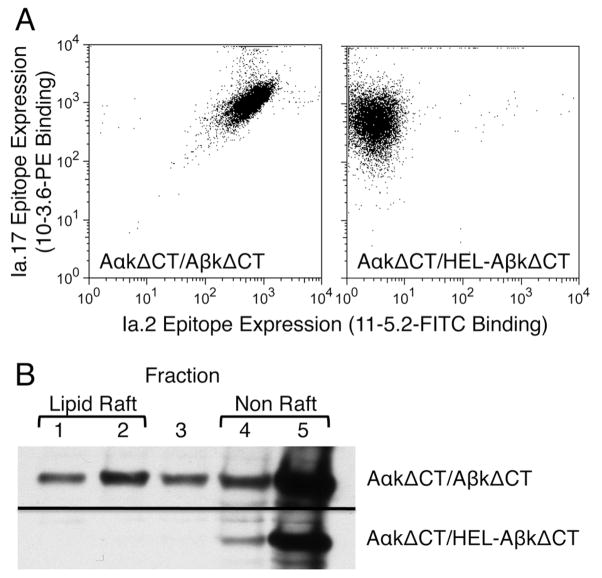

Since the Ia.2+ class II subset is normally found in lipid rafts, the impact of adding a β chain tethered peptide on class II lipid raft partitioning was next determined. IIA1.6 B cells were stably transfected with either Ia.2+ AαkΔCT/AβkΔCT (I-Ak-ΔCT) or Ia.2− AαkΔCT/HEL-AβkΔCT (HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT) and clones expressing similar levels of total I-Ak class II (i.e., Ia.17) were selected for analysis (Figure 5A). When lipid rafts were isolated from transfectants where cell surface class II was tagged with anti-Ia.17-btn, it became apparent that while Ia.2+ I-Ak-ΔCT exhibits a level of raft partitioning similar to wild type I-Ak (Figure 5B, compare to Figure 2A), Ia.2– HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT is absent from plasma membrane lipid rafts (Figure 5B). This altered plasma membrane distribution suggests that the Ia.2 epitope [defined by the 11-5.2 mAb that binds Aαk near the peptide binding region of the molecule (6, 7)] marks a distinct conformational state of the I-Ak protein that has a higher “affinity” for lipid raft membrane domains.

FIGURE 5. Addition of a class II tethered peptide abolishes class II lipid raft localization.

Panel A: IIA1.6 B cells were stably transfected to express tailless I-Ak or tailless I-Ak possessing a tethered HEL peptide. Cells were stained with 11-5.2-FITC and 10-3.6-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Panel B: Surface I-Ak class II of stably transfected IIA1.6 cells was tagged with 10-3.6-biotin and streptavidin-HRP and the cells warmed to 37°C for 5 minutes. Cells were then lysed in TNE 1% TX-100, lipid rafts isolated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation (16, 17), and the distribution of the biotin-tagged anti-class II mAb was detected by probing a western blot of the sucrose fractions with streptavidin-HRP. Shown are representative results of 1 of 3 experiments.

The Ia.2 positive subset of class II is central to efficient T cell stimulation

Since lipid raft resident peptide-class II complexes play a central role in CD4 T cell activation (27–29), the role of the Ia.2+ subset of lipid raft-resident class II molecules in antigen presentation was investigated. Both I-Ak-ΔCT and HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT transfectants express levels of total I-Ak class II (Ia.17) similar to that of the endogenous wild type I-Ak class II molecules expressed by TA3 cells (Figures 1C and 5A). Moreover, direct staining with the HEL47-62–I-Ak specific mAb Aw3.18 reveals that a significant amount of the HEL47-62–I-Ak construct expressed by the HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT cells traffics to the cell surface with the tethered peptide bound in the class II peptide binding groove (Figure 6A, 0μM HEL).

To test the antigen presentation capabilities of all three types of I-Ak class II molecules (i.e. wild type, I-Ak-ΔCT and HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT), TA3 or I-Ak transfected B cells were pulsed overnight with 100 μM HEL protein (a treatment that does not modulate expression of the Ia.2 epitope) and the resulting levels of HEL47-62–I-Ak complexes determined by staining with Aw3.18 (Figure 6A). Both TA3 and I-Ak-ΔCT cells pulsed with 100 μM HEL protein exhibit a similar increase in expression of cell surface HEL47-62–I-Ak complexes, demonstrating that both WT and ΔCT class II molecules are capable of being loaded with exogenous antigen derived peptides. In addition, HEL-pulsed HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT cells also exhibit a statistically significant increase in Aw3.18 binding (Figure 6A), demonstrating that at least a fraction of the Ia.2– I-Ak molecules expressed by these cells can be loaded with exogenous antigen derived peptides.

To test the relative T cell stimulatory activity of Ia.2+ and Ia.2– HEL47-62–I-Ak peptide-class II complexes, the ability of all three B cell lines (pulsed with varying doses of HEL protein) to activate HEL47-62–I-Ak reactive Ly50 T cells was tested (Figure 6B). For TA3 cells (expressing wild type I-Ak) and I-Ak-ΔCT B cells, addition of increasing amounts of HEL protein results in a similar dose-dependent increase in T cell activation. In contrast, HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT B cells elicit significantly less T cell activation upon addition of exogenous antigen. Moreover, the HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT B cells also fail to activate Ly50 T cells in the absence of added HEL protein, even though the cells express significant levels of tethered HEL47-62–I-Ak complexes detectable with the Aw3.18 mAb (Figure 6A). While the lack of T cell stimulation by the HEL–I-Ak-ΔCT B cells could be due to a “blocking” effect of the tethered peptide, this is unlikely because the tethered peptide-class II complexes are recognized by the Aw3.18 mAb (Figure 6A), which recognizes the same HEL47-62–I-Ak complex as the Ly50 TCR.

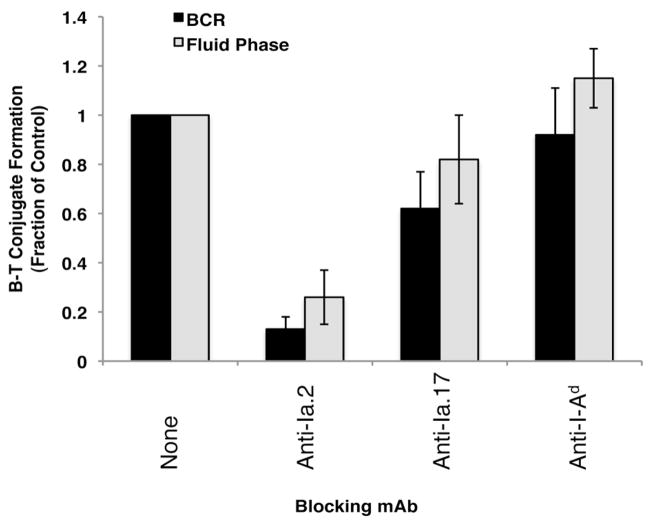

To extend the analysis of T cell activation by Ia.2+ class II to non-transformed B cells, the role of Ia.2+ class II in antigen presentation by splenic B cells was investigated. While immunologically relevant B cell antigen presentation occurs subsequent to the BCR-mediated processing of cognate antigen, B cells can also process and present non-cognate antigen internalized via fluid-phase endocytosis. Moreover, previous studies have established that in splenic B cells these two distinct pathways of antigen processing result in the formation of functionally distinct peptide-class II complexes that differ in their ability to elicit B cell activation (13). Specifically, BCR-mediated processing results in the formation of Type I peptide-class II complexes whereas fluid-phase antigen processing results in the formation of Type II complexes. Therefore, the impact of anti-Ia.2 mAb on the formation of B cell–T cell conjugates via either Type I or Type II peptide-class II complexes was determined [for these studies anti-Ia.2 mAb was not used to block induction of T cell cytokine production as anti-Ia.2 binding elicits B cell activation (10), introducing a confounding variable into T cell activation studies]. As shown by the results presented in Figure 7, pre-binding of anti-Ia.2 to the Ia.2+ subset of class II molecules profoundly inhibits B cell–T cell conjugate formation via both Type I and Type II HEL-I-Ak peptide-class II complexes. In contrast, binding of the anti-Ia.17 mAb (which binds all cell surface I-Ak, but which does not efficiently hinder TCR binding) exhibits only a partial inhibitory effect at best. These results establish that both BCR-mediated and fluid-phase antigen processing result in formation of Ia.2+ antigenic peptide–class II complexes and that these Ia.2+ signaling-competent lipid raft-resident cell surface peptide–class II complexes are critical to cognate B cell–T cell interactions.

FIGURE 7. The 11-5.2 anti-Ia.2 mAb efficiently blocks B cell-T cell interactions via both BCR and fluid phase generated peptide-class II complexes.

B cells expressing BCR or fluid phase generated peptide-class II complexes were labeled with anti-B220-PE, co-cultured with anti-Thy-1.2-FITC labeled HEL47-62–I-Ak-specific Ly50 T cells and the level of B cell–T cell conjugates determined by flow cytometry. Antibody inhibitors (used at saturating concentrations) were pre-bound to B cells and maintained throughout the assay. Bars indicate the average level of B cell–T cell conjugates (n=4) formed under each condition (relative to the no inhibitor control) ± 1 S.D. Statistics: 11-5.2 blocking vs. no blocking mAb, p ≤ 0.01 for both Type I and Type II complexes.

Discussion

This report establishes that the Ia.2 epitope defines a conformational subset of lipid raft resident I-Ak class II molecules that are critically involved in MHC class II-restricted B cell–T cell interactions. These observations are consistent with previous studies establishing the critical role of lipid raft resident peptide-class II complexes in T cell activation especially when antigen is present at limiting concentrations (23, 27, 28, 30). More importantly, these data uncover an additional level of complexity in the structure and function of MHC class II that significantly impacts our understanding of MHC class II-restricted antigen processing and presentation.

Two significant questions arising herein are the structural basis for the Ia.2 epitope, and perhaps of greater significance the explanation for why Ia.2+ class II molecules exhibit enhanced lipid raft partitioning? Initially, the finding that addition of a class II tethered peptide (which prevents CLIP-mediated class II-Ii interactions) blocks Ia.2 expression suggested that Ii-mediated delivery of class II to MIIC may drive acquisition of the Ia.2 epitope. However, sub-cellular fractionation studies suggest this is not the case. Moreover, the finding that Ia.2+ class II can be found associated with Ii means that acquisition of the Ia.2 epitope occurs early in the biosynthetic pathway, possibly within the endoplasmic reticulum.

Since Ia.2+ class II is found in lipid rafts, which have an ordered lipid structure distinct from the disordered lipid structure of the non-raft region of the membrane, it is more likely that the conformational differences between Ia.2+ and Ia.2− class II molecules involves the transmembrane domain of the molecule. Consistent with this scenario, it has been reported that transmembrane domain mutants of the I-Ak class II molecule lose expression of the Ia.2 epitope while retaining the Ia.17 epitope (9). Furthermore, prior studies have established a CLIP-independent role of the transmembrane domain of the Ii protein in class II–Ii interactions (31). Therefore, addition of the class II tethered peptide may ablate Ia.2 epitope expression by altering class II–Ii transmembrane domain interactions in the endoplasmic reticulum (or other sub-cellular compartment), resulting in class II-Ii complexes incapable of adopting the Ia.2+ conformation. This possibility is currently under investigation.

Functional studies were the first hint that Ia.2+ class II represents a subset of class II molecules (10). Likewise, Type A vs. Type B peptide-class II complexes were also initially defined on a functional basis (2). While the precise structural differences between Type A and Type B complexes remain unknown, it is well established that formation of Type A complexes is DM-dependent, whereas Type B complexes appear to be destroyed upon interaction with the DM chaperone. Initially, the idea that Ia.2+ class II molecules might correspond to either Type A or Type B complexes was very attractive. However, both Ia.2+ as well as Ia.2− class II molecules are found in DM-rich MIIC (an environment that would lead to the rapid destruction of Type B complexes) suggest that this is not the case. Nevertheless, a more subtle role for DM in the formation of Ia.2+ vs. Ia.2− peptide-class II complexes is still a matter of active investigation.

Another MHC class II “conformational” variant that impacts T cell activation is the formation of class II “dimer-of-dimers” [i.e., a dimer of MHC class II αβ dimers (32)]. In 1999 Wade and colleagues examined the effect of mutations that disrupt I-Ak dimer-of-dimers formation on T cell activation and anti-I-Ak mAb binding [including anti-Ia.2 and anti-Ia.17 mAbs (33)]. Their results demonstrated that while multiple class II mutants that inhibit I-Ak dimer-of-dimers formation significantly impact T cell activation, these mutations fail to alter the ratio of anti-Ia.2 vs. anti-Ia.17 mAb binding. Their results indicate that formation of the Ia.2 epitope is not dependent on the formation of I-Ak dimer-of-dimers. However, it will require additional investigation to address related questions such as whether Ia.2+ vs. Ia.2− class II complexes differ in their inherent ability to form class II dimer-of-dimers.

Another potential explanation for the unique structure and function of the Ia.2+ subset of class II may reside in the association of known MHC class II “accessory” proteins, such as the CD79 signaling subunit of the BCR (25) as well as multiple members of the tetraspan family of proteins [e.g., CD9 (21), CD20 (34), CD82 (35)], which have been shown to be able to form lipid raft-like membrane domains (36). Since 293T cells lack CD79, the results presented in Figure 4 rule out the likelihood that the Ia.2 epitope marks pre-existing class II-CD79 complexes. However, the potential role of one or more tetraspan proteins remains an open question as multiple members of the tetraspan family of proteins are expressed in many cell types.

In summary, this report establishes that the Ia.2 epitope (recognized by the widely used 11-5.2 anti-I-Ak mAb) defines a conformational subset of 10–20% of cell surface I-Ak MHC class II molecules that exhibit a high level of partitioning into plasma membrane lipid rafts. This discovery highlights a previously unappreciated level of MHC class II structural heterogeneity and defines a new tool for the investigation of MHC class II biology. The results also establish that the Ia.2 bearing class II conformer found in lipid rafts is critically important for the formation of cognate B cell–T cell interactions and subsequent T cell activation. Future studies to define the mechanism of generation of the Ia.2 epitope will provide greater insight into MHC class II structure and function as well as the molecular mechanisms that control membrane protein partitioning into distinct membrane micro-domains.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Karen Duus (Albany Medical College) for generating and providing the HEK293T-CIITA cells, Dr. Bill Wade (Dartmouth) for Ly50 T cells, Lisa Drake, Allison Yelton and Kelly Hughes for excellent technical assistance as well as the Immunology Core Facility and Animal Resources Facility at Albany Medical College.

Footnotes

This work was supported by N.I.H. grant AI-083922 to J.A.H. and J.R.D.

Abbreviations: btn, biotin; CT, cytoplasmic tail; CTB, cholera toxin B subunit; DM, HLA-DM/H-2M; HEL, hen egg lysozyme; Ii, invariant chain; IP, immunoprecipitation; PGS, protein G-sepharose; PI, propidium iodide; TNE, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM EDTA; TX-100, Triton X-100; WCL, whole cell lysate

References

- 1.Sadegh-Nasseri S, Stern LJ, Wiley DC, Germain RN. MHC class II function preserved by low-affinity peptide interactions preceding stable binding. Nature. 1994;370:647–650. doi: 10.1038/370647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovitch SB, Unanue ER. Conformational isomers of a peptide-class II major histocompatibility complex. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:293–313. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein J. The major histocompatibility complex of the mouse. Science. 1979;203:516–521. doi: 10.1126/science.104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oi VT, Jones PP, Goding JW, Herzenberg LA. Properties of monoclonal antibodies to mouse Ig allotypes, H-2, and Ia antigens. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1978;81:115–120. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-67448-8_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierres M, Devaux C, Dosseto M, Marchetto S. Clonal analysis of B- and T-cell responses to Ia antigens. I. Topology of epitope regions on I-Ak and I-Ek molecules analyzed with 35 monoclonal alloantibodies. Immunogenetics. 1981;14:481–495. doi: 10.1007/BF00350120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landais D, Matthes H, Benoist C, Mathis D. A molecular basis for the Ia.2 and Ia.19 antigenic determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:2930–2934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landias D, Beck BN, Buerstedde JM, Degraw S, Klein D, Koch N, Murphy D, Pierres M, Tada T, Yamamoto K, et al. The assignment of chain specificities for anti-Ia monoclonal antibodies using L cell transfectants. J Immunol. 1986;137:3002–3005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braunstein NS, Germain RN. Allele-specific control of Ia molecule surface expression and conformation: implications for a general model of Ia structure-function relationships. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:2921–2925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosson P, Bonifacino JS. Role of transmembrane domain interactions in the assembly of class II MHC molecules. Science. 1992;258:659–662. doi: 10.1126/science.1329208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nashar TO, Drake JR. Dynamics of MHC class II-activating signals in murine resting B cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:827–838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGovern EM, Moquin AE, Caballero A, Drake JR. The effect of B cell receptor signaling on antigen endocytosis and processing. Immunol Invest. 2004;33:143–156. doi: 10.1081/imm-120030733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gondre-Lewis TA, Moquin AE, Drake JR. Prolonged antigen persistence within nonterminal late endocytic compartments of antigen-specific B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2001;166:6657–6664. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nashar TO, Drake JR. The pathway of antigen uptake and processing dictates MHC class II-mediated B cell survival and activation. J Immunol. 2005;174:1306–1316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dadaglio G, Nelson CA, Deck MB, Petzold SJ, Unanue ER. Characterization and quantitation of peptide-MHC complexes produced from hen egg lysozyme using a monoclonal antibody. Immunity. 1997;6:727–738. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amigorena S, Drake JR, Webster P, Mellman I. Transient accumulation of new class II MHC molecules in a novel endocytic compartment in B lymphocytes. Nature. 1994;369:113–120. doi: 10.1038/369113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caballero A, Katkere B, Wen XY, Drake L, Nashar TO, Drake JR. Functional and structural requirements for the internalization of distinct BCR-ligand complexes. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:3131–3145. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Putnam MA, Moquin AE, Merrihew M, Outcalt C, Sorge E, Caballero A, Gondre-Lewis TA, Drake JR. Lipid raft-independent B cell receptor-mediated antigen internalization and intracellular trafficking. J Immunol. 2003;170:905–912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fremont DH, Monnaie D, Nelson CA, Hendrickson WA, Unanue ER. Crystal structure of I-Ak in complex with a dominant epitope of lysozyme. Immunity. 1998;8:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosloniec EF, Gay D, Freed JH. Epitopic analysis by anti-I-Ak monoclonal antibodies of I-Ak-restricted presentation of lysozyme peptides. J Immunol. 1989;142:4176–4183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubreuil PC, Birnbaum DZ, Caillol DH, Lemonnier FA. Identification on I-Ak molecules of a functional site recognized by proliferating T-lymphocytes. Immunogenetics. 1982;16:407–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00372100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zilber MT, Setterblad N, Vasselon T, Doliger C, Charron D, Mooney N, Gelin C. MHC class II/CD38/CD9: a lipid-raft-dependent signaling complex in human monocytes. Blood. 2005;106:3074–3081. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becart S, Setterblad N, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Ono SJ, Charron D, Mooney N. Intracytoplasmic domains of MHC class II molecules are essential for lipid-raft-dependent signaling. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2565–2575. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiltbold EM, Poloso NJ, Roche PA. MHC class II-peptide complexes and APC lipid rafts accumulate at the immunological synapse. J Immunol. 2003;170:1329–1338. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell RN, Shaw AC, Weaver YK, Leder P, Abbas AK. Cytoplasmic tail deletion converts membrane immunoglobulin to a phosphatidylinositol-linked form lacking signaling and efficient antigen internalization functions. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8856–8860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang P, Stolpa JC, Freiberg BA, Crawford F, Kappler J, Kupfer A, Cambier JC. TCR-induced transmembrane signaling by peptide/MHC class II via associated Ig-alpha/beta dimers. Science. 2001;291:1537–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5508.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drake JR, Lewis TA, Condon KB, Mitchell RN, Webster P. Involvement of MIIC-like late endosomes in B cell receptor-mediated antigen processing in murine B cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:1150–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson HA, Hiltbold EM, Roche PA. Concentration of MHC class II molecules in lipid rafts facilitates antigen presentation. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:156–162. doi: 10.1038/77842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poloso NJ, Roche PA. Association of MHC class II-peptide complexes with plasma membrane lipid microdomains. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setterblad N, Becart S, Charron D, Mooney N. B cell lipid rafts regulate both peptide-dependent and peptide-independent APC-T cell interaction. J Immunol. 2004;173:1876–1886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poloso NJ, Muntasell A, Roche PA. MHC class II molecules traffic into lipid rafts during intracellular transport. J Immunol. 2004;173:4539–4546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castellino F, Han R, Germain RN. The transmembrane segment of invariant chain mediates binding to MHC class II molecules in a CLIP-independent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:841–850. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<841::aid-immu841>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schafer PH, Pierce SK, Jardetzky TS. The structure of MHC class II: a role for dimer of dimers. Semin Immunol. 1995;7:389–398. doi: 10.1006/smim.1995.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nydam T, Wade TK, Yadati S, Gabriel JL, Barisas BG, Wade WF. Mutations in MHC class II dimer of dimers contact residues: effects on antigen presentation. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1237–1249. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.8.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szollosi J, Horejsi V, Bene L, Angelisova P, Damjanovich S. Supramolecular complexes of MHC class I, MHC class II, CD20, and tetraspan molecules (CD53, CD81, and CD82) at the surface of a B cell line JY. J Immunol. 1996;157:2939–2946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammond C, Denzin LK, Pan M, Griffith JM, Geuze HJ, Cresswell P. The tetraspan protein CD82 is a resident of MHC class II compartments where it associates with HLA-DR, -DM, and -DO molecules. J Immunol. 1998;161:3282–3291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy S, Shoham T. The tetraspanin web modulates immune-signalling complexes. Nature reviews. 2005;5:136–148. doi: 10.1038/nri1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmeister JK, Cooney D, Coggeshall KM. Clustered CD20 induced apoptosis: src-family kinase, the proximal regulator of tyrosine phosphorylation, calcium influx, and caspase 3-dependent apoptosis. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2000;26:133–143. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2000.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vilen BJ, Nakamura T, Cambier JC. Antigen-stimulated dissociation of BCR mIg from Ig-alpha/Ig-beta: implications for receptor desensitization. Immunity. 1999;10:239–248. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80024-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vilen BJ, Burke KM, Sleater M, Cambier JC. Transmodulation of BCR signaling by transduction-incompetent antigen receptors: implications for impaired signaling in anergic B cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:4344–4351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cambier JC, Morrison DC, Chien MM, Lehmann KR. Modeling of T cell contact-dependent B cell activation. IL-4 and antigen receptor ligation primes quiescent B cells to mobilize calcium in response to Ia cross-linking. J Immunol. 1991;146:2075–2082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]