Abstract

Background: Clinical decisions for seriously ill older patients with surgical emergencies are highly complex. Measuring the benefits of burdensome treatments in this context is fraught with uncertainty. Little is known about how surgeons formulate treatment decisions to avoid nonbeneficial surgery, or engage in preoperative conversations about end-of-life (EOL) care.

Objective: We sought to describe how surgeons approach such discussions, and to identify modifiable factors to reduce nonbeneficial surgery near the EOL.

Design: Purposive and snowball sampling were used to recruit a national sample of emergency general surgeons. Semistructured interviews were conducted between February and May 2014.

Measurements: Three independent coders performed qualitative coding using NVivo software (NVivo version 10.0, QSR International). Content analysis was used to identify factors important to surgical decision making and EOL communication.

Results: Twenty-four surgeons were interviewed. Participants felt responsible for conducting EOL conversations with seriously ill older patients and their families before surgery to prevent nonbeneficial treatments. However, wide differences in prognostic estimates among surgeons, inadequate data about postoperative quality of life (QOL), patients and surrogates who were unprepared for EOL conversations, variation in perceptions about the role of palliative care, and time constraints are contributors to surgeons providing nonbeneficial operations. Surgeons reported performing operations they knew would not benefit the patient to give the family time to come to terms with the patient's demise.

Conclusions: Emergency general surgeons feel responsible for having preoperative discussions about EOL care with seriously ill older patients to avoid nonbenefical surgery. However, surgeons identified multiple factors that undermine adequate communication and lead to nonbeneficial surgery.

Introduction

Due to demographic shifts, increasing numbers of older patients, many with life-limiting serious illness, are presenting with emergent surgical conditions.1 Outcomes after emergency surgery in older patients are often poor.1,2 National data show that among patients 65 years and older who undergo emergency laparotomy, 16% die in-hospital and 30% die within six months.3,4 Many suffer postoperative complications (40%–80%),5 which contribute to increased health care utilization and functional decline.1,5–8 Moreover, studies reveal that seriously ill patients prioritize function, cognition, and time at home above longevity.9,10 Concurrently, pressure from policymakers to evaluate appropriateness of interventions near the end of life (EOL) is growing.11

Almost one-fifth of Medicare beneficiaries undergo surgery in their final month.12 The type of care that patients receive at the EOL is often determined during a crisis, but achieving goal-concordant EOL care requires clinicians to discuss treatment options in the context of a patient's goals and priorities.13 Little is known about how surgeons accomplish this in the emergent setting.

In light of growing evidence describing potential harms of overly aggressive treatments14,15 and high rates of burdensome surgery at the EOL,12 we hypothesize that barriers to communication between surgeons and patients in the emergent setting contribute to nonbeneficial treatments. In this study we sought to (1) describe how surgeons approach treatment decisions and discussions about EOL care for older seriously ill patients with surgical emergencies and (2) identify modifiable factors to reduce nonbeneficial surgery near the EOL.

Methods

This study was approved by Partners Health Care Research Committee.

Participants/recruitment

Purposive and snowball sampling was used to recruit a national sample of general surgeons. Investigators e-mailed 95 professional contacts directly and asked potential participants to identify others who might meet inclusion criteria. Nonresponders were contacted twice before being deemed nonparticipants. Participants underwent semistructured interviews by telephone between February and May 2014. Verbal consent was obtained; interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed.

Interview guide

A semistructured interview guide was developed by an acute care surgeon (ZC) and a psychiatrist (SB), both with experience in palliative medicine, with input from an interdisciplinary advisory team. The goal of the guide was to understand how surgeons approach treatment decisions for seriously ill older patients with acute surgical conditions. It included questions about personal experience making treatment decisions, attitudes about discussing EOL care, the role of palliative care, and approaches to communication with patients and surrogates. Additionally, the interview included clinical vignettes (see Fig. 1) asking participants to assume the consulting surgeon role, formulate prognoses, and make clinical recommendations. Participants explained how they would discuss the patient's condition and approach treatment decisions with patients or surrogates in these contexts. Open-ended questions were used. Prognostic estimates were ascertained using Likert-scale response categories.

FIG. 1.

Clinical vignettes used in structured interview guide to understand how surgeons approach treatment decisions for seriously ill older patients with acute surgical conditions.

Analysis

Qualitative analysis using grounded theory approach was performed in two stages by three independent coders using NVivo software (NVivo version 10.0, QSR International). First, one coder conducted structural content analysis identifying themes regarding how surgeons define nonbeneficial surgery, elements in decision making, attitudes about discussing EOL care and palliative care, approaches to communication, and barriers to preventing nonbeneficial surgery. Following this generation of themes, a code list was developed. Next, a primary coder conducted in-depth thematic analysis identifying six summary domains. For internal validity, a second coder double-coded a subset of transcripts. The research team met regularly to ensure coding consistency. Research team members have expertise in public health, surgery, palliative care, psychiatry, qualitative research, and quantitative research, which facilitated in-depth and experience-informed data interpretation. Quantitative prognostic data is described using mean point estimates and range provided by individual participants.

Results

Twenty-four surgeons were interviewed (see Table 1). Their mean age was 43 (median 42) years. All were general surgeons; 46% had additional critical care training. Most identified emergency surgery as ≥50% of their practice (75%), and most were consulted for surgical conditions in older patients with advanced illness “sometimes” or “very often” in the last three months (91.6%).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Surgeons (n = 24) | |

| Age, years, mean (median) | 43 (42) |

| 30–39 | 5 (20.8%) |

| 40–49 | 16 (66.7%) |

| 50–59 | 2 (8.3%) |

| 60–69 | 1 (4.2%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 (66.6%) |

| Female | 8 (33.3%) |

| Subspecialtya | |

| Surgical critical careb | 11 (45.8%) |

| Year of surgical training | |

| 1980–1989 | 1 (4.2%) |

| 1990–1999 | 3 (12.5%) |

| 2000–2009 | 13 (54.1%) |

| 2010–2015 | 7 (29.2%) |

| Portion of practice that is emergency surgery | |

| >90% | 2 (8.3%) |

| 50%–89% | 16 (66.7%) |

| 25%–49% | 5 (20.8%) |

| <25% | 1 (4.2%) |

| Number of times consulted for surgical conditions in elderly patients with advanced illness in last three months | |

| Very often | 14 (58.3%) |

| Sometimes | 8 (33.3%) |

| Rarely | 2 (4.2%) |

| Never | 0 (0%) |

All participants were general surgeons; other specialization was by self-report.

There was overlap between participants who considered acute care surgery as their subspecialty and those with training in surgical critical care.

Domains

All participants expressed that improved communication with seriously ill patients and their families during surgical emergencies is crucial to avoid nonbeneficial interventions. Six domains describing factors that affect communication during surgical emergencies were identified (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Domains that Affect Communication with Seriously Ill Patients with Acute Surgical Conditions

| Domain | Key issues identified | Surgeon comments |

|---|---|---|

| Surgeon responsibility | • Surgeons feel responsible to have these conversations with patients | “Once you call me and you ask me to do something that is potentially harmful to a human being as a direct result of my hand, regardless of whether or not you want me to discuss EOL issues with a patient is irrelevant. If you ask me to cut on them, I will have those discussions. I think it's obligatory, and I think it is part of the informed consent process.” |

| • Surgeons feel responsible to not offer futile care and advise patients only to undergo operations where benefits outweigh harm | ||

| • Care teams may disagree on what is best for the patient; once involved, surgeons feel it is their responsibility to discuss EOL with the patient | ||

| Assessing surgical risk | • Prognosis is difficult to determine due to lack of data and difficult to relay to the patient | “Keeping them alive on a tube is…unfair. But none of us can really speak to, Are they suffering? I don't know. We don't THINK they're having pain, we don't THINK they're conscious of what's going on, but I don't know.” |

| • Poor functional status preoperatively predicts poor outcomes | ||

| • Even with the worst prognosis, surgery is seen as doing something to give the patient a chance | “There is still a good chance that he would die soon after [surgery], but it would be his chance.” | |

| Appropriateness of treatment | • Appropriateness of a treatment depends on the individual's goals, which should be determined before the operation and cascade of treatments begin | Interviewer: “Sure. Okay. So, would you ask specifically to him and his families about things like advance directives, or treatment preferences, quality of life postcare?” |

| • Suffering is a part of surgery, even when it is done to improve QOL | Participant: “Yeah. I'd also give them the possibility that he may develop organ failure, uh, kidney failure, respiratory failure, and possibly need, other extending therapies, like…a feeding tube, and are those things that he wants.” | |

| • If the underlying chronic illness cannot be fixed, several invasive procedures won't prolong overall survival and will reduce QOL | ||

| • Surgeons should focus on the final outcome of a treatment course including mortality and QOL rather than fixing an immediate problem in patients with underlying serious illness | “Everything we do has a cost. Whether it's a financial cost, or an emotional cost to the family, or, pain and suffering to the patient themselves. Everything we do to a patient causes them discomfort and has risks involved, so everything we do should be [with] an eye towards improving the QOL for patients. Especially elderly patients, with acute illnesses.” | |

| “I'm sure they've said that you do need surgery if this is going to be fixed; the question is, Do we really want to fix it?” | ||

| Patient and family factors | • Patients and families are often poorly prepared to make decisions in the acute setting because of a lack of understanding regarding the prognosis of their chronic condition and heightened emotions | “Many times they just don't have the medical knowledge and the preparedness, and the experience and the understanding of what's to come to make an intelligent decision. I mean, it's entirely based on emotion.” |

| • Surgeons sometimes offer nonbeneficial operations to give patients' families time to cope with the patient's condition | “Well, there are times when I think that you can do a nonbeneficial procedure that's not gonna benefit the patient, per se, but may allow time for the family to come to terms with the realities of that patient's care.” | |

| • Other times, surgeons are not affected by the patient's or family's emotional state | “No, I don't change my recommendations or my clinical assessment of a patient based on the emotional reaction of family members or the decision makers.” | |

| Attitudes about EOL care and palliative care | • Some surgeons view palliative care as having an active role in patient care, while others view palliative care as a transition away from active treatment to doing nothing | Interviewer: “Did you think about introducing palliative care?” |

| Participant: “So we talked about the option of not doing anything…and they indicated they would want to do SOMETHING. So, we didn't go any further down that pathway.” | ||

| System factors | • Conversations are time consuming | “Yeah, of course we always have a responsibility. Time is frequently what limits our ability to fulfill that responsibility.” |

| • Problems obtaining longitudinal information in the medical record | ||

| • Palliative care availability varies |

EOL, end of life; QOL, quality of life.

Domain 1: Surgeon responsibility

Participants felt that “discussing EOL decisions is our [surgeons'] responsibility”; however, they agreed that it is best if EOL issues are discussed before surgical consultation occurs. Many participants felt that discussions should occur preoperatively, because patients may not be able to express themselves after the operation, and family members may not be able to reach consensus regarding the patient's preferences. They also reported that discussing mortality is often necessary for informed consent.

Participants discussed their responsibility to not offer futile care: “Because I'm the surgeon…I'm the one who's going to…carry the cross, I'm the one who's gonna have a burden to bear if I provide nonbeneficial care.” One noted barrier to fulfilling this responsibility was ‘doctor shopping’—requesting successive consultations until a surgeon who agrees to operate is found. Surgeons also reported that referring clinicians sometimes perceive them as technicians who perform procedures without independent judgment. One participant stated, “Oh, we've called the surgeon, we've ordered the procedure just like we order an oil change.… I think that's wrong, because what I do can harm a human being by my direct hand.” However, in several instances participants noted that surgeons should not change their recommendations or actions due to pressure from colleagues.

Domain 2: Assessing risk

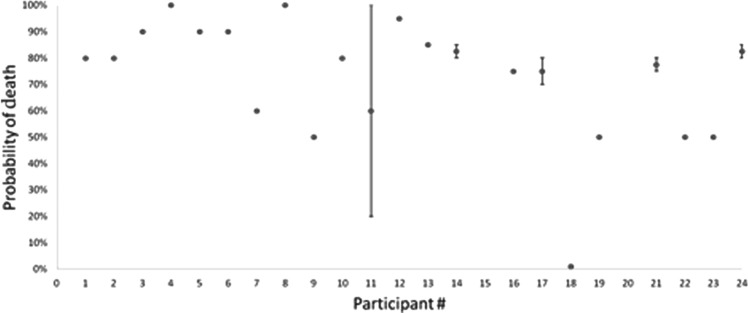

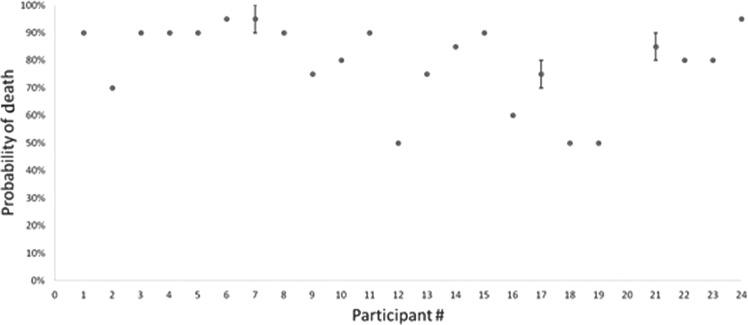

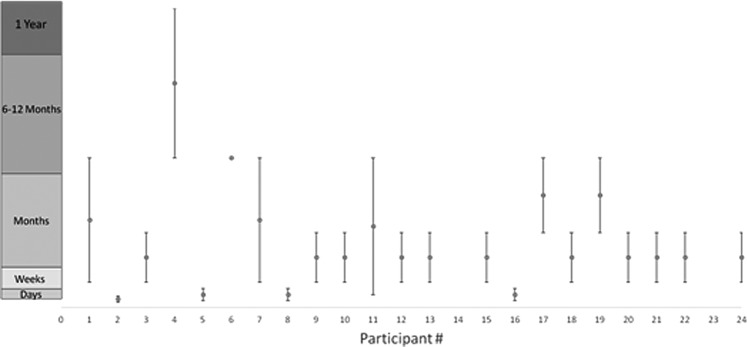

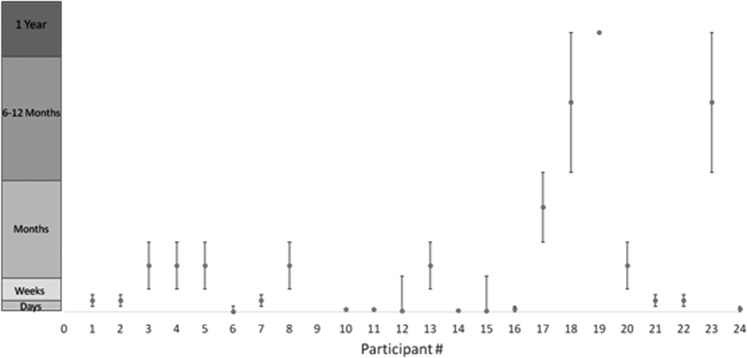

Participants were asked to estimate prognosis (with and without surgery) for clinical scenarios (see Fig. 1). Two participants could not provide a prognosis for vignette 1, and one participant could not provide a prognosis for vignette 2, as they found it too difficult to quantify. Life expectancy estimates with surgery ranged from days to over a year, with most participants (>85%) estimating mean survival as ≤6 months for each vignette (see Figs. 2 and 4). The range of prognostic estimates without surgery was 20%–100% risk of death for vignette 1 and 50%–100% for vignette 2 (see Figs. 3 and 5).

FIG. 2.

Vignette 1: Probability of death within 72 hours without an operation.

FIG. 4.

Vignette 2: Probability of death within 72 hours without an operation.

FIG. 3.

Vignette 1: Length of survival if an operation is performed.

FIG. 5.

Vignette 2: Length of survival if an operation is performed.

Two primary themes in surgeons' responses regarding risk estimation were identified. First, they had difficulty formulating prognosis due to lack of clear data about postoperative outcomes. Several participants discussed the use of preoperative functional status as crucial to assessing potential outcomes to formulate a prognosis, but felt this was imperfect. In discussing risk, most participants said they focus on survival statistics. However, several participants expressed frustration regarding the lack of data about postoperative functional status and quality of life (QOL) to support their recommendations, stating that providing such information is important. “Keeping them alive on a tube is…unfair. But, none of us can really speak to, Are they suffering? We don't think they're having pain, we don't think they're conscious of what's going on, but I don't know.” Second, surgeons often gauge that for patients with poor prognosis, even a small chance at survival with surgery seems worthwhile.

Domain 3: Appropriateness

Participants distinguished whether an operation could or should be done by discussing the patient's goals and how those goals fit into the burdens and benefits of an intervention. Acceptable surgical treatments were those able to provide a QOL consistent with the patient's goals, focusing on final health outcomes, rather than fixing immediate problems. “I'm sure they've said that you do need surgery if this is going to be fixed; the question is, do we really want to fix it?”

Identifying goals of care, participants suggest, would be less challenging if there was a structured approach to these conversations. One surgeon suggested that the absence of such a “framework…can prolong the dying process.”

When discussing postoperative care, participants stated that agreeing to surgery could subject patients to a cascade of nonbeneficial medical treatment. When an underlying problem cannot be fixed, several procedures are performed, causing increased suffering without improving survival or QOL. Surgeons reported that they frequently rely on postoperative conversations to reevaluate an intensive treatment course after an emergent operation; they describe regularly seeking opportunities for patients to “opt-out” of treatments if the patient will not get better. “If you don't ask…[about goals of care], it can actually get you down a path that the patient never really wanted.”

Several participants noted that suffering is part of any surgical treatment. “Everything we do has a cost. Whether it's a financial cost, or an emotional cost to the family, or…pain and suffering to the patient…so, everything we do should be with an eye towards improving the QOL for patients.” Participants felt that patients' poor understanding about their underlying condition's prognosis hinders their ability to appreciate how an acute event will change their QOL, impacting their ability to make goal-concordant decisions.

Domain 4: Patient and family

Patients' emotions and religious beliefs about illness and death were described as factors that influence a patient's or family's ability to absorb information, as well as surgeons' decision making. Some surgeons said they “wouldn't be doing [their] job” if they let families' emotions influence their decisions. Others said they are more likely to operate if the family or patient is emotionally unprepared. For example, “it [emotions] may influence me more to go to the operating room, just to buy them some time…. And to some degree that's not fair to the patient.”

All participants agreed that patients or surrogates who are unprepared for EOL conversations—emotionally or in lack of understanding of their illness—complicate an already difficult situation. These conversations require more time to allow unprepared patients or surrogates to process medical information and identify preferences. One participant noted, “Most people aren't able to really process what QOL means when you're in the emergency department in pain and at risk of dying.” Consequently, complex treatment decisions are often too difficult for unprepared patients and families; some felt that when surgeons become the primary decision makers, patients receive better care.

Participants held different views as to the type of patient-provider relationship most conducive to surgical decision making. Although most stated that lacking an established relationship can be a barrier to communication, a few noted that because they are meeting patients for the first time, they have the “benefit of being a fairly objective, second eye,” which they felt could improve communication.

Domain 5: Palliative care

Participants' views on the role and definition of palliative care ranged from an active role in controlling symptoms, helping families cope, and improving QOL, to ‘doing nothing’: “Interviewer: Did you think about introducing palliative care? Participant: So we talked about the option of not doing anything…and they indicated they would want to do something. So, we didn't go any further down that pathway.” Requesting palliative care consultations was limited by concerns that recommending these consults was not their place, lack of access to palliative care in the emergency department, or beliefs that palliative care would not solve the patient's problem.

Domain 6: System factors

Time constraints hinder surgeons' ability to fulfill responsibilities regarding communication to their patients. For example, time to discuss goals and wishes preoperatively must be weighed against the risk of a patient's condition declining and “significantly altering their chances of survival.” Surgeons also found it difficult for patients and families to determine an acceptable QOL in situations where death was otherwise imminent.

A historical understanding of the patient's condition and treatment course emerged as an important factor in determining ongoing treatment options. Barriers to data gathering included frequently rotating staff, incomplete records, and inability to reach other providers in a timely fashion. Without longitudinal medical data, one participant noted, “You just kind of go [to the operating room].” There was general agreement that EOL conversations should happen prior to the development of emergent conditions to prepare seriously ill patients for decision making.

Discussion

This study gives valuable insight into how surgeons approach deliberations about surgery in seriously ill older patients with acute surgical conditions, and highlights gaps in understanding among surgeons of the potential role of palliative care in treating these patients. Surgeons described a sense of responsibility to have conversations about EOL care, including discussing goals of care, appropriateness of treatments, and outcomes (i.e., disease trajectory, survival, and QOL). In formulating treatment decisions, surgeons place value on weighing surgical burdens and benefits, considering patients' goals inconsistently. Surgeons vary in their willingness and ability to estimate and discuss prognosis. They believe that patients and families are often poorly prepared to engage in these conversations, and surgeons may find themselves performing operations to give the family time to come to terms with the final outcome. Surgeons find value in discussing EOL care to guide treatment decisions, but have varying views on the utility and role of palliative care. Finally, participants identified system factors that influence communication, including time constraints and poor information flow.

Participants in this study preferred to elicit advance directives and preferences for life-sustaining treatments before emergency surgery in order to avoid the potential postoperative ‘cascade’ of nonbeneficial treatments. They also expressed a willingness, and even desire, to renegotiate treatment goals postoperatively to prevent harm. This is in contrast to ‘surgical buy-in,’ a complex process seen in the elective setting in which surgeons negotiate with patients preoperatively to commit to any postoperative care necessary to achieve a good outcome.16 Moreover, in elective operations most surgeons decline to perform high-risk surgery on patients whose directives limit postoperative care.17 This contrast of communication practices between elective and emergency surgery appears to stem from the high degree of uncertainty in the emergent setting, and may also be shaped by the number of participants interviewed who were both emergency surgeons as well as intensivists. Others have shown that surgeons are more likely to focus on survival as the primary goal, whereas intensivists weigh scarcity of resources and QOL in their decision.18 Nonetheless, our findings suggest differences in how preferences for perioperative life-sustaining treatments are considered across surgical settings. Improving care for seriously ill surgical patients requires that quality measures, such as those tracked by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project and Medicare, hold surgeons accountable for documenting treatment preferences, and delivering care consistent with those preferences.19

Surgeons in this study were widely inconsistent in their prognostic estimates. Surgeons, like other physicians, are generally poor at formulating and communicating prognosis.20,21 Difficulty prognosticating may reflect inexperience with patients who opt for nonoperative care. Moreover, surgical risk calculators, such as National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), Surgical Apgar Score, and Physiological and Operative Severity for the enUmeration of Morbidity and Mortality (POSSOM),22–24 are limited to predicting mortality and complications in the immediate postoperative period and do not include other meaningful outcomes such as longer-term mortality, function, or QOL. More work is needed to develop robust data on patient-oriented outcomes after surgery and familiarize surgeons with prognostic tools for seriously ill patients. Our data demonstrate that currently, patients and families receive highly variable information depending on which surgeon is on-call.

Another important finding is that surgeons operate on patients to help families cope even when they do not think it will help the patient. A previous study suggests that patients are willing to undergo treatments if they think it will reduce their family's suffering;25 however, invasive operations might be avoided by improving preoperative communication. When a family's prognostic understanding is not established before an emergency, they are less capable of fully grasping the impact of this event as an inflection point in the patient's health trajectory.20,21,25,26 Additionally, the current medical system lacks the necessary infrastructure to support acute grief in the emergent setting.27 Together, these factors make nonbeneficial treatments appealing in an attempt to gain control in an otherwise uncontrolled and distressing situation.

This study found that utilization of palliative care consultation varies in the acute setting due to availability and surgeons' perceptions. With an estimated survival of six months or less, palliative care would have been appropriate in each of our vignettes.28 Yet surgeons were reluctant to consider this option, which they frequently equated with ‘doing nothing’ or patient abandonment. Reluctance to forgo life-prolonging treatment may stem from surgeons' ‘rescue credo,’ an exaggerated sense of accountability for patient outcomes, traditionally cultivated in surgical training and reinforced in morbidity and mortality conferences.29,30

The Institute of Medicine report, Dying in America, recommends that palliative care be made available to all patients with serious illness, and that all clinicians who treat them become skilled in primary palliative care.11,31,32 In the emergency surgical setting, palliative care clinicians can be useful by offering skilled communication, managing symptoms, helping families cope, and providing a vision of a peaceful death as an achievable outcome for patients unlikely to benefit from surgery. While availability of palliative care specialists is a problem in some settings,33 low consultation rates by surgeons might also be due to negative views of their utility.34 Our findings support the need to improve collaboration between these clinicians, and to develop new models of effective surgical/palliative care teamwork. In addition, surgeons would benefit from basic palliative care education to better fulfill their role as primary palliative care providers specifically in areas of perioperative discussions, decision management, and goal setting.31

This study should be considered in light of important limitations. First, it only considers the surgeon's perspective. Further work assessing key elements of these deliberations from other views should be done. In addition, surgeons who participated were mostly early-career academic surgeons. The youth of the surgeons interviewed is consistent with current trends towards more junior surgeons taking emergency call.13 However, a more seasoned sample may hold different views on EOL communication and confidence in prognostication. Finally, the generalizability of our findings regarding prognosis came from a small sample; large quantitative surveys are needed to confirm these results.

Surgeons experience and express a great sense of responsibility for conversations about goals of care and desires for EOL care during deliberations with seriously ill older patients about emergent surgery. However, patients are undergoing nonbeneficial operations due to inadequate communication between surgeons, the patient, and family. Such communication would be greatly improved if surgeons received training in palliative care and EOL communication, had access to more relevant outcomes data, and partnered with palliative care clinicians to improve care delivery.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Parekh AK, Barton MB: The challenge of multiple comorbidity for the US health care system. JAMA 2010;303:1303–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neary WD, Foy C, Heather BP, et al. : Identifying high-risk patients undergoing urgent and emergency surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006;88:151–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper Z, Mitchell SL, Gorges RJ, et al. : Predictors of mortality in older patients >30 days after emergent major abdominal operation: Data from the health and retirement survey. J Am Coll Surg 219:S53 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoneham M, Murray D, Foss N: Emergency surgery: The big three: Abdominal aortic aneurysm, laparotomy and hip fracture. Anaesthesia 2014;69:70–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scarborough JE, Pappas TN, Bennett KM, et al. : Failure-to-pursue rescue: Explaining excess mortality in elderly emergency general surgical patients with preexisting “do-not-resuscitate” orders. Ann Surg 2012;256:453–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson TN, Wallace JI, Wu DS, et al. : Accumulated frailty characteristics predict postoperative discharge institutionalization in the geriatric patient. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213:37–42, discussion 42–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, et al. : Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg 2005;242:326–341, discussion 341–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, et al. : Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72:1526–1530, discussion 1530–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gramling R, Norton S, Ladwig S, et al. : Latent classes of prognosis conversations in palliative care: A mixed-methods study. J Palliat Med 2013;16:653–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper Z, Courthwright A, Karlage A, et al. : Pitfalls in communication that lead to nonbeneficial emergency surgery in elderly patients with serious illness: Description of the problem and elements of a solution. Ann Surg 2014;260:949–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine: Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. The National Academies Press, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, et al. : The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2011;378:1408–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aprahamian C, Wallace JR, Bergstein JM, et al. : Characteristics of trauma centers and trauma surgeons. J Trauma 1993;35:562–567, discussion 567–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, et al. : Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1061–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. : Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarze ML, Bradley CT, Brasel KJ: Surgical “buy-in”: The contractual relationship between surgeons and patients that influences decisions regarding life-supporting therapy. Crit Care Med 2010;38:843–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redmann AJ, Brasel KJ, Alexander CG, et al. : Use of advance directives for high-risk operations: A national survey of surgeons. Ann Surg 2012;255:418–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cassell J, Buchman TG, Streat S, et al. : Surgeons, intensivists, and the covenant of care: Administrative models and values affecting care at the end of life—updated. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1551–1557, discussion 1557–1559 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dy SM, Kiley KB, Ast K, et al. : Measuring what matters: Top-ranked quality indicators for hospice and palliative care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:773–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aslakson RA, Wyskiel R, Shaeffer D, et al. : Surgical intensive care unit clinician estimates of the adequacy of communication regarding patient prognosis. Crit Care 2010;14:R218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaefer KG, Block SD: Physician communication with families in the ICU: Evidence-based strategies for improvement. Curr Opin Crit Care 2009;15:569–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. : Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: A decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:833–842, e1–e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gawande AA, Kwaan MR, Regenbogen SE, et al. : An Apgar score for surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones HJ, de Cossart L: Risk scoring in surgical patients. Br J Surg 1999;86:149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner JS, Roth J: Avoiding iatrogenic harm to patient and family while discussing goals of care near the end of life. J Palliat Med 2006;9:451–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walczak A, Butow PN, Davidson PM, et al. : Patient perspectives regarding communication about prognosis and end-of-life issues: How can it be optimised? Patient Educ Couns 2013;90:307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fauri DP, Ettner B, Kovacs PJ: Bereavement services in acute care settings. Death Stud 2000;24:51–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 9, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, pp. 35–36. www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guideance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c09.pdf (last accessed April13, 2016)

- 29.Buchman TG, Cassell J, Ray SE, et al. : Who should manage the dying patient? Rescue, shame, and the surgical ICU dilemma. J Am Coll Surg 2002;194:665–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosk C: Forgive and Remember: Managing Medical Failure, 2nd ed. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2003, p. 279 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quill TE, Abernethy AP: Generalist plus specialist palliative care: Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Task Force on Surgical Palliative Care Committee on Ethics. Statement of Principles of Palliative Care. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons. 2005;90:34–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reville B, Foxwell AM: The global state of palliative care: Progress and challenges in cancer care. Ann Palliat Med 2014;3:129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ernst KF, Hall DE, Schmid KK, et al. : Surgical palliative care consultations over time in relationship to systemwide frailty screening. JAMA Surg 2014;149:1121–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]