Abstract

Background

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) is used as part of treatment in a variety of clinical conditions. Its use in the treatment of ulcerative colitis has been reported in few clinical reports.

Objective

We report the effect of HBO on refractory ulcerative colitis exploring one potential mechanism of action.

Design

A review of records of patients with refractory ulcerative colitis who received HBO was conducted. Clinical and histopathological scoring was utilised to evaluate the response to HBO therapy (HBOT).

Results

All patients manifested clinical improvement by the 40th cycle of HBOT. The median number of stool frequency dropped from seven motions/day (range=3–20) to 1/day (range=0.5–3), which was significant (z=−4.6, p<0.001). None of the patients manifested persistent blood passage after HBOT (z=−3.2, p=0.002). The severity index significantly improved after HBOT (z=−4.97, p<0.001). Histologically, a significant reduction of the scores of activity was recorded accompanied by a significant increase in the proliferating cell nuclear antigen labelling index of the CD44 cells of the colonic mucosa (p=0.001).

Conclusions

HBOT is effective in the setting of refractory ulcerative colitis. The described protocol is necessary for successful treatment. HBOT stimulates colonic stem cells to promote healing.

Keywords: CHRONIC ULCERATIVE COLITIS, GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING, ULCERATIVE COLITIS, INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Summary box.

What is already known about this subject?

-

▸

Hyperbaric oxygen has been proposed as a therapy for several diseases.

-

▸

Hyperbaric oxygen has an anti-inflammatory effect.

-

▸

Hyperbaric oxygen might be useful in ulcerative colitis.

What are the new findings?

-

▸

Hyperbaric oxygen stimulates colonic stem cells.

-

▸

Hyperbaric oxygen seems be useful in the treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

-

▸

This modality is readily available.

-

▸

It is inexpensive compared to other lines.

-

▸

It might have an additional benefit by replenishing the general condition of patients.

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease characterised by colonic mucosal ulcers and a disturbing alteration of bowel habits.1 The disease is manifested in the active phase by increased frequency of bowel motions with or without lower gastrointestinal bleeding. These manifestations are reversed by induction of mucosal healing and subsiding inflammation.2 Genetic susceptibility,3 alteration of bacterial flora,4 immune dysfunction5 and abnormal cytokine production6 are implicated factors, among others,7 in the pathogenesis of UC. The 5-aminosalicylate acid (5-ASA) class of drugs is considered first line therapy as it induces remission in the majority of patients with mild and moderate disease.8 Patients with severe disease require adjuvant therapeutic lines involving corticosteroids and immune modulators.9 Although these medications are effective in many cases, in other cases, these lines are not effective.10 Moreover, they could have significant adverse effects particularly after long-term use.11

Hyperbaric oxygen (ie, the use of 100% oxygen inhalation in a pressurised room) has been in clinical use as a therapeutic option for a variety of medical conditions.12–14 Nevertheless, the utility of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) to treat inflammatory bowel diseases did not receive attention until recently and its use in gastrointestinal conditions is not yet well established. Several experimental studies have been conducted on laboratory animal models with induced intestinal diseases such as ischaemia15 and inflammation.16 Among others, these experiments demonstrated the strong potential for the use of HBO in the treatment of various gastrointestinal conditions, with promising results.17 Only a few clinical studies have reported the use of HBOT in the treatment of UC.18 Stem cell activation was one of the proposed mechanisms of the action of HBOT.19

Objective

This study aims at presenting our clinical experience in the use of HBO for the treatment of refractory UC, investigating the status of colonic stem cells to delineate a possible mechanism of action for HBOT in this clinical setting.

Study setting

The study was conducted at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Alexandria, Egypt.

Methods

In 1994, a woman with unresponsive severe UC was referred to undergo hyperbaric oxygen sessions to improve her general condition prior to a scheduled colectomy. After 40 sessions, the patient’s general condition improved remarkably along with complete remission of her colonic symptoms, therefore surgery was deferred. Thereafter, we systematically offered HBO sessions to patients with refractory UC.

After institutional review board approval (IRB), records of patients with refractory UC who were referred for HBOT were retrieved from a prospectively maintained cohort. Those with documented pre-therapy and post-therapy endoscopic and histopathological data were included in this study.

Between 1994 and 2011, 32 consecutive patients with refractory UC were treated with HBOT. We considered UC refractory when there was minimal or no response after 4–6 weeks of continuous standard medical therapy. Besides the dietary management based on a well-balanced plan, rich in protein, complex carbohydrates, whole grains and fats, our standard medical therapy was composed of an escalating regime of 3.2–4.8 g oral 5-ASA/day with a 4 g (5-ASA) enema/day. In more severe cases, 40–50 mg of oral methylprednisolone were given daily and tapered over 4–6 weeks along with 2–2.5 mg/kg/day of oral azathioprine. Patients with clinically more severe disease were given intravenous corticosteroids (60 mg prednisolone/day). Patients were judged to have refractory disease when no more than minimal clinical improvement, based on the Mayo Clinic Disease Severity Index, manifested after 4–6 weeks of maximal dose therapy.20

HBOT was performed in two multiplaced hyperbaric chambers. The first chamber was a Sebi—a Gorman design built in England in 1973, with a 200 cm diameter—which was used until 2003. Thereafter, a second chamber, a Haux Starmed 2000—built in Germany in 2002, with a 200 cm diameter—was used. Patients were subjected to gradual compression and decompression at 2–3 psi/min (pounds per square inch) with air at the beginning and end of each session.

The total oxygen breathing time was 60 min with a 5 min air break at 30 min. The hyperbaric cycles were given at a pressure depth of 2.8 atmospheric absolute (ATA) (equivalent to 18 m). The sessions were repeated five times per week for eight consecutive weeks. All patients received their medical therapy contemporaneously with the hyperbaric sessions.

From 1 to 3 weeks after completion of the hyperbaric sessions, a follow-up colonoscopy was performed and multiple punch biopsies were taken from different areas during the examination. The majority of colonoscopic examinations were performed after colon preparation.

Endoscopic grading was assigned following scores described in the Mayo Clinic Grading Scale.20 We did not keep data on the severity of blood passage per anus, hence we only had information on the presence or absence of blood passage. Therefore we calculated the severity score index using 9 instead of 12 levels.

All endoscopic examinations were performed by a single consultant (YT) and the cohort data maintained by the senior author (EM).

Morphometric analysis

All morphological evaluations were performed by one of the authors (NB) blinded to the patients’ codes. At least 18 serial sections of every biopsy were examined and histopathological scores of activity given according to the adopted scoring system from Geboes.21 Scores were assigned to the different categories according to the worst area in the examined biopsy. A standard point-counting method22 was used to quantitate CD44 positivity, using Steptovidin–perioxidase (ab64269, Abcam, USA), to estimate the number of stem cells in the mucosa. Towards that end, 12 consecutive non-overlapping fields were evaluated in quantification of CD44 positivity, using an Olympus microscope (CH 20 BIMF 200, Olympus, China) under a magnification of ×400. A total of 81×12 points (number of intersections in the grid used) were evaluated in each biopsy. All glandular profiles in the biopsy were point counted. All positively stained points falling on the grid's cross-points were counted. Negatively stained glandular epithelial cells falling on the intersections of the counting grid were also counted.

The mean score per biopsy was calculated. The results are expressed as the percentage of positively stained points of the total number of points counted.

The proliferating cell nuclear antigen labelling index (PCNA/LI) was counted as a percentage of nuclei counted in a field of 0.15 mm of an ×400 magnification, using the following formula: number of positively staining nuclei/number of positively stained nuclei and number of negatively stained nuclei.22

During evaluation of the biopsy, only positively stained glandular epithelial cells with deeply stained nuclei were counted as positive. Fields with positively stained inflammatory cells, smooth muscle fibres or fibroblasts, were ignored.

Statistical analysis

The continuous data are expressed in mean±SD, and median and range, according to the normality of distribution test. The significance of differences between the clinical groups (before and after treatment) was determined by Wilcoxon signed rank test, and used for non-parametric paired data. Correlations between the different parameters were performed using the Spearman's rank correlation test. A p value of <5% was considered significant. All analysis was performed using the statistical software package SPSS V.20 (IBM Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

The median age of the included patients was 34.5 years (range 19–50). Fifty per cent of the patients were females. All the patients (100%) included in the present study who underwent HBOT therapy for refractory UC demonstrated a remarkably favourable clinical improvement as well as improvement in both, the endoscopic and histopathologic parameters used for assessment of the response to therapy.

Clinical evaluation

All patients manifested clinical improvement by the 40th cycle of HBOT. The median number of stool frequency in the pre-HBOT stage was 7 motions/day (range=3–20), which was significantly (z=−4.6, p<0.001) decreased to a median of 1 motion/day (range=0.5–3). None of the patients manifested persistent blood passage after the HBOT (z=−3.2, p=0.002).

Endoscopic evaluation and activity scoring

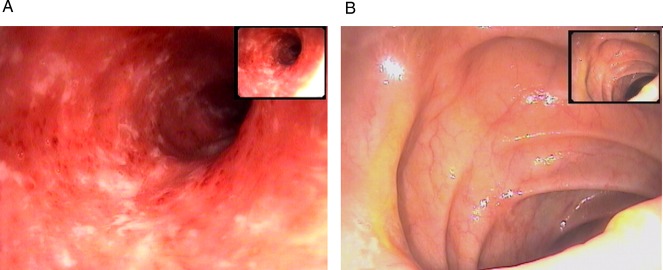

Endoscopic evaluation demonstrated a highly significant reduction of disease activity scores (z=−5.156, p<0.001). The pre-HBOT scores were (median=2, range=1–3) as compared with the post-HBOT scores (median=0, range=0–1) (figures 1–3). Table 1 summarises the patients’ disease severity scoring.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic picture of ulcerative colitis with (A) Mayo grade 2 score with significant oedema, absent vessel markings and small ulcers, (B) Mayo grade 0 score of the same patient showing inactivity of the disease post-treatment colonoscopy.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic picture of ulcerative colitis with (A) Mayo grade 3 score with significant oedema, absent vessel markings and spontaneously bleeding ulcers, (B) Mayo grade 1 score of the same patient showing significant reduction of the activity of the disease post-treatment colonoscopy.

Figure 3.

Endoscopic picture of ulcerative colitis with (A) Mayo grade 3 score with friable mucosa and large ulcers. (B) Mayo grade 0 score of the same patient showing inactive disease post-treatment colonoscopy.

Table 1.

Summary of patients’ disease severity index according to the Mayo Clinic20

| Pre-HBOT | Post-HBOT | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stool frequency (median/range) | 7 (3–20) | 1 (0.5–3) | <0.001 |

| Blood passage (number of patients) | 10 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Endoscopy | |||

| Grade 0 | 0 | 25 | <0.001† |

| Grade I | 2 | 7 | |

| Grade II | 20 | 0 | |

| Grade III | 10 | 0 | |

| Severity score index‡ (median/range) | 7 (5–9) | 0 (0–3) | <0.001 |

*p Value driven from the Wilcoxon singed ranks test. †p Value is calculated using the same test for the central tendency and dispersion of all grades, not only grade 0.

‡Scoring was calculated using 9 instead of 12 levels, due to the absence of detailed data about severity of passage of blood per anus, which was excluded from the nominator.

HBOT, hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

The median disease severity index was 7 (range=5–9) in the pre-HBOT assessment sheets, which was significantly decreased to a median of 0 (range=0–3) after the HBOT (z=−4.97, p<0.001).

Histopathological evaluation

Histologically, a significant reduction in the scores of activity was recorded and is summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Histopathological changes of the mucosa induced by hyperbaric oxygen therapy in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis

| Pathological feature | Median* (range) Pre-therapy |

Median (range) Post-therapy |

p Value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural changes | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) | >0.05 |

| Chronic inflammation | 1.3 (1.2–1.3) | 1.1 (1–1.1) | <0.001 |

| Eosinophils in the lamina propria | 2.15 (2–2.5) | 2.05 (2–2.2) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils in the lamina propria | 2.1 (2.0–2.1) | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils in the epithelium | 3.3 (3.1–3.3) | 3.1 (3.1–3.2) | <0.001 |

| Crypt destruction | 4.3 (4.1–4.3) | 4.1 (4–4.1) | <0.001 |

| Surface erosions/ulcerations | 5.3 (5.2–5.3) | 5.1 (5.0–5.1) | <0.001 |

*The median was used to express the central tendency instead of the mean rank, to facilitate interpretation by the reader.

†p Value is estimated from Wilcoxon signed rank test.

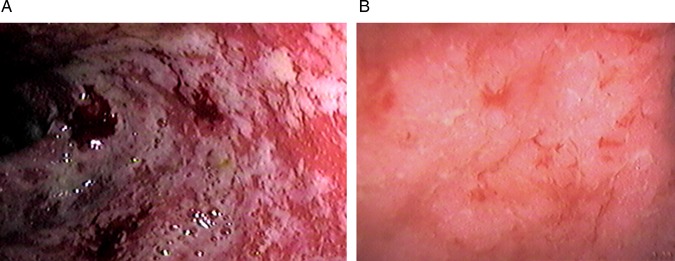

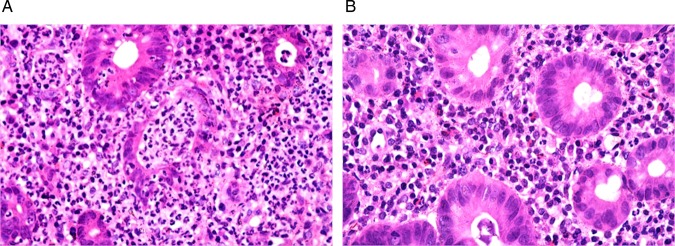

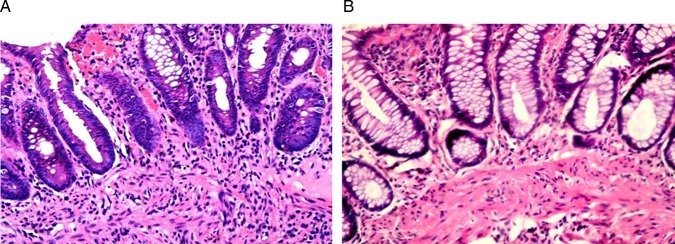

The chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria (figure 4), the numbers of neutrophils infiltrating the lamina propria (figure 5) and the surface epithelium (figure 6), crypt destruction and surface erosions/ulcerations (figure 7), were observed. Signs of chronicity as architectural distortion did not exhibit significant improvement (p>0.05).

Figure 4.

Pre (A) and post (B) biopsies showing marked reduction of the intensity of the inflammatory infiltrate in the mucosa (H&E, ×200).

Figure 5.

Pre (A) and post (B) treatment biopsies showing marked reduction in the numbers of neutrophils in the lamina propria and crypt epithelium (H&E, ×400).

Figure 6.

Pre (A) and post (B) treatment biopsies showing marked reduction in the numbers of neutrophils in the surface epithelium (H&E, ×400).

Figure 7.

Pre (A) and post (B) treatment biopsies showing significant mucosal healing (H&E stain, ×200).

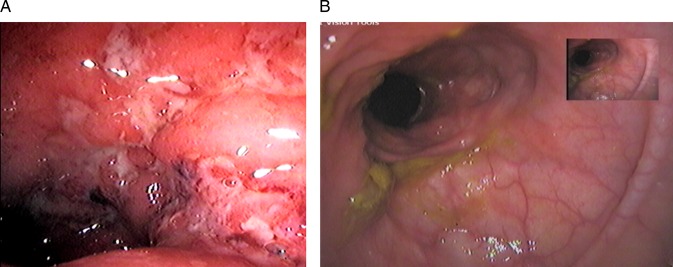

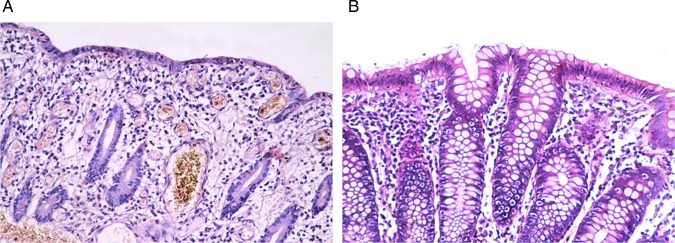

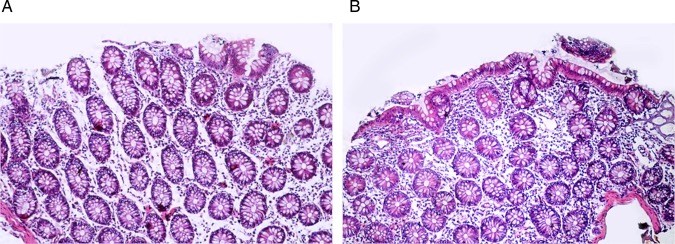

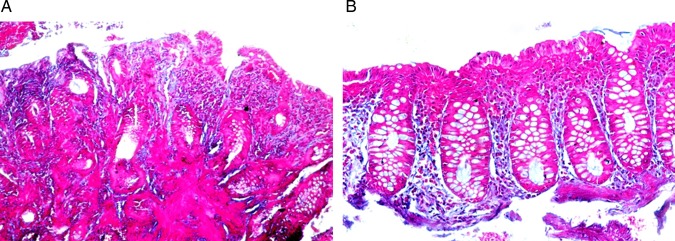

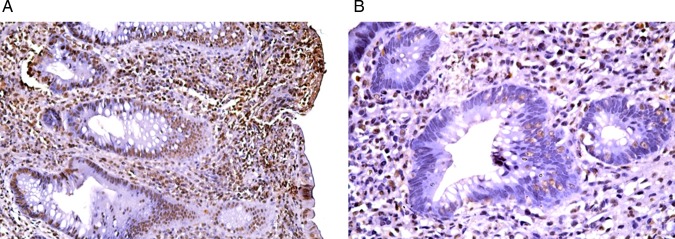

Other signs of healing observed in the post-treatment biopsies included a significant increase in the degree of fibrosis of the lamina propria (figure 8), as well as restoration of the goblet cell component of the glands (figure 9).

Figure 8.

Pre- (A) and post- (B) treatment biopsies showing an increase in the degree of fibrosis of the lamina propria in the post-treatment biopsy (Masson Trichrome, ×100).

Figure 9.

Pre (A) and post (B) treatment biopsies showing restoration of the goblet cell component of the epithelium (H&E, ×200).

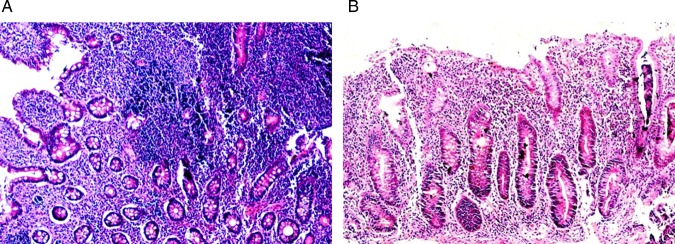

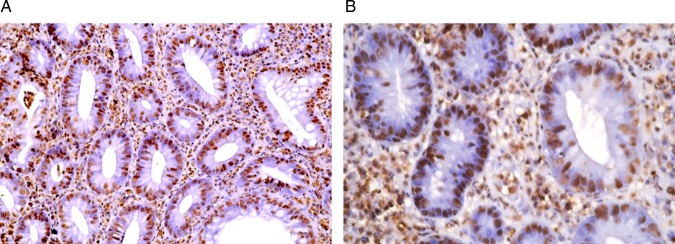

Immunohsitochemical determination of the numbers of CD44 positive stem cells in the colonic biopsies

PCNA labelled the nuclei of the epithelial cells and inflammatory cells as well as the fibroblasts. A significant increase (p=0.001) in the PCNA/LI was observed in the post-treatment biopsies as compared with the pre-treatment biopsies (x=20.56+1.88, range=18–26 vs x=16.03+1.09, range=14–18, respectively) (figures 10 and 11).

Figure 10.

A section of a pre-treatment colonic biopsy in the active stage (A) showing a well developed crypt abscess. <(B)> Note the PCNA/LI (PCNA, streptavidin peroxidase, (A) ×200, (B) ×400).

Figure 11.

Section of a post-treatment colonic biopsy showing a high PCNA/LI (PCNA, streptavidin peroxidase, (A) ×200, (B) ×400).

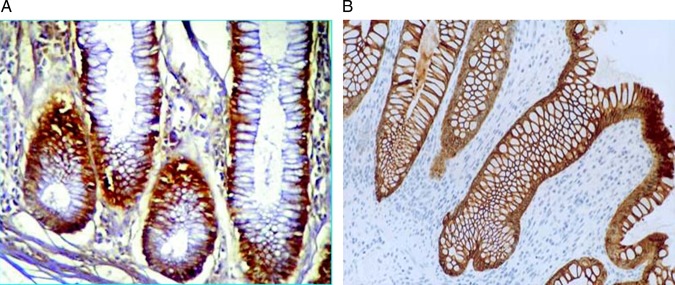

CD44 positivity was observed in the membranes of the glandular epithelium. A significant increase (p=0.001) was observed between pretreatment and post-treatment biopsies; (x=6.56+0.5, range=6–7) in the pre-treatment (x=9.13+0.61, range=8–12) versus in the post-treatment biopsies (figure 12). This increase was accompanied by a significant increase in the PCNA/LI (p=0.001).

Figure 12.

Pre and post-treatment biopsies showing an increase in CD44 membranous staining (CD44 monoclonal antibody, streptavidin peroxidase technique, ×200).

In the post-treatment biopsies, a significant correlation was detected between the PCNA/LI and CD44 positivity (r=0.86, p=0.001). Also, a significant correlation was seen between the scores of the erosions and the PCNA/LI (r=6.82, p=0.008) as well as, in an inverse pattern, between the scores of inflammation and CD44 positivity (r=−0.813, p=0.001).

Discussion

Our series is one of the largest reported in the English literature, with documented mucosal healing in cases of UC treated with HBOT. In this study, the use of hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of refractory UC proved to be effective. This adds to the accumulating evidence on the efficacy of HBOT in the treatment of UC.18 Moreover, it promotes mucosal healing, which is a primary target for all therapeutic regimens of UC.2

One of the recognised intermediate mechanisms in UC is mucosal hypoxia.23 This could be supported by the presence of reduced rectal blood supply in some affected individuals.24 Mucosal hypoxia increases the oxidative stress factors that lead to reduction of mitochondrial functions25 with further expression of inflammatory factors,26 which, in turn, reduces oxygenation through increased oedema formation. Hyperbaric oxygen is suggested to exert its effect through reducing the inflammation and promoting mucosal healing.27 28 It induces down regulation of the hypoxia-induced inflammation.29

One of the proposed mechanisms of action of HBOT is promoting mucosal healing by increasing the numbers of stem cells in the colonic mucosa. It promotes the differentiation of colonic stem cells, resident in the colonic mucosal crypts, and migration of bone marrow stem cells to the colonic mucosa,30 to aid in the repair process.

CD44 has been found to be a marker of stem cells activity in several organs, including the colon.31 32 In the present study, CD44 was found to be increased in post-treatment biopsies and to correlate with mucosal glandular epithelial cell proliferation and mucosal healing.

Ditschkowski et al33 reported the clinical improvement of UC symptoms following allogeneic stem cell transplant, which is supported by our findings. The influence of HBOT along with stem cell transplant is reported to be more profound than stem cell transplant alone, in an experimental study.34 In our study, it appears that the stimulation of stem cell activity plays an important role in the remission of disease activity. This is in line with the reported sentinel role of stem cells as an anti-inflammatory guardian,35 which was found to down regulate inflammation.36

The observed increase in the fibrosis score in post-treatment biopsies in the present study is another mechanism of action of HBOT. HBOT is reported to stimulate the proliferation of fibroblasts in a dose-dependent fashion.37 The deposition of fibroblasts in the different subepithelial layers could explain the insignificant change of the architecture despite the significant improvement of all parameters of the utilised histopathological scoring system.

On the other hand, there are reports of potential complications of HBOT. Simsek et al,38 in an experimental study, reported that repeated exposure to hyperbaric oxygen could lead to accumulation of oxidative stress in the lung tissue. A few complications have also been reported in clinical settings following hyperbaric therapy for clinical conditions other than UC.39 40

There were no adverse effects inflicted by HBOT following our therapeutic protocol. A low complication rate was reported in different clinical reports of UC treated with hyperbaric oxygen,41 42 and for other clinical conditions.43 Moreover, when compared with other therapeutic lines for the treatment of refractory UC, no studies reporting on the clinical use of HBOT for UC reported any significant complications.18

There was no unified therapeutic protocol in the published literature for the use HBOT in UC.44 45 Buchman et al46 reported successful therapy in a single case at a pressure of 2 ATA. In our patients, we noticed that a pressure of 2.8 ATA was important for the therapy to be effective.

In the present study, we used two chambers for treatment delivery, as reported in the ‘Methods’ section of this paper. Treatment sessions at the older chamber (Sebi Gorman, 1973) were delivered at 2.8 ATA. At the beginning of the use of the newer chamber (Haux Starmed, 2000), treatments were delivered at a pressure of 2.5 ATA (equivalent to 15 m). Treatments given at this pressure were not as clinically successful as expected. On modifying treatment pressures to 2.8 ATA, the treated patients demonstrated significant improvement. Four patients were treated first with 2.5 ATA pressure protocol and were not included in this study, to avoid the possible influence of a synergistic dose effect. The heterogeneity of the reported therapeutic protocols could be attributed to the limited number of published cases, the variation in the definition of refractoriness and the severity of disease in each series as well as the different patient demographics.41 44 46

Reduction in the cost of care has been demonstrated for other diseases treated with HBO.47 Although the same concept applies for refractory UC, no sufficient data are currently available to support this information for UC therapy. Nonetheless, it would be much cheaper when compared to relatively new therapeutic lines such as infliximab. Recent reports demonstrated the efficacy of infliximab in refractory UC.48 None of the patients in this report received this treatment.

The major caveat of this study is the non-controlled design. Nonetheless, our results are encouraging for future randomised controlled studies to be conducted to provide stronger evidence on the true value of hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of refractory and even non-refractory UC, and to further explore the possible therapeutic mechanisms of HBO in the treatment of UC.

Conclusion

HBOT is effective in the setting of refractory UC. The described protocol is necessary for successful treatment. The mechanism of action of HBOT in treatment of refractory cases of UC involves stimulation of colonic stem cells to promote healing.

Footnotes

Contributors: MB and NB equally contributed to this manuscript. KK, YT, KET and EM critically revised the manuscript. EM discovered the influence of hyperbaric oxygen on patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. He continued to treat these patients similarly over the past decade. KET was responsible for the hyperbaric oxygen therapy protocols. YT was responsible for all colonoscopic procedures. NB was responsible for all histopathological assessments.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board, Faculty of Medicine, University of Alexandria.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 1998;115:182–205. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70381-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casellas F, Barreiro de Acosta M, Iglesias M, et al. Mucosal healing restores normal health and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;24:762–9. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835414b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volk BA, Gerok W. [Current insights on the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases]. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax 1992;81:863–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke DA, Axon AT. Adhesive Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel disease and infective diarrhoea. BMJ 1988;297:102–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.297.6641.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuman MG. Immune dysfunction in inflammatory bowel disease. Transl Res 2007;149:173–86. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2006.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadakis KA, Targan SR. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med 2000;51:289–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucharzik T, Maaser C, Lügering A, et al. Recent understanding of IBD pathogenesis: implications for future therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:1068–83. doi:10.1097/01.mib.0000235827.21778.d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulder CJ, Tytgat GN, Weterman IT, et al. Double-blind comparison of slow-release 5-aminosalicylate and sulfasalazine in remission maintenance in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1988;95:1449–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taba Taba Vakili S, Taher M, Ebrahimi Daryani N. Update on the management of ulcerative colitis. Acta Med Iran 2012;50:363–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meier J, Sturm A. Current treatment of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:3204–12. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i27.3204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:1909–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61084-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.[No authors listed] Hyperbaric oxygen for multiple sclerosis. BMJ 1984;289:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for wound healing–part II. Tecnologica MAP Suppl 1999;Oct:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdullah MS, Al-Waili NS, Butler G, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen as an adjunctive therapy for bilateral compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure after heroin intake. Arch Med Res 2006;37:559–62. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dockendorf BL, Frazee RC, Peterson WG, et al. Treatment of acute intestinal ischemia with hyperbaric oxygen. South Med J 1993;86:518–20. doi:10.1097/00007611-199305000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rachmilewitz D, Karmeli F, Okon E, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen: a novel modality to ameliorate experimental colitis. Gut 1998;43:512–18. doi:10.1136/gut.43.4.512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guven A, Gundogdu G, Uysal B, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy reduces the severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in a neonatal rat model. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44:534–40. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossignol DA. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and analysis. Med Gas Res 2012;2:6 doi:10.1186/2045-9912-2-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thom SR. Hyperbaric oxygen: its mechanisms and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127(Suppl 1):131S–41S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181fbe2bf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1625–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM198712243172603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geboes K, Riddell R, Ost A, et al. A reproducible grading scale for histological assessment of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gut 2000;47:404–9. doi:10.1136/gut.47.3.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Koraie AF, Baddour NM, Adam AG, et al. Cytoskeletal protein expression and regenerative markers in schistosomal nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;17:803–12. doi:10.1093/ndt/17.5.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Maltezos E, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha and 2alpha overexpression in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol 2003;56:209–13. doi:10.1136/jcp.56.3.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLeod RS, Churchill DN, Lock AM, et al. Quality of life of patients with ulcerative colitis preoperatively and postoperatively. Gastroenterology 1991;101:1307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magalhães J, Ascensão A, Soares JM, et al. Acute and severe hypobaric hypoxia increases oxidative stress and impairs mitochondrial function in mouse skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 2005;99:1247–53. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01324.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semenza GL. Oxygen sensing, homeostasis, and disease. N Engl J Med 2011;365:537–47. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1011165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Waili NS, Butler GJ. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen on inflammatory response to wound and trauma: possible mechanism of action. ScientificWorldJournal 2006;6:425–41. doi:10.1100/tsw.2006.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akin ML, Gulluoglu BM, Uluutku H, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen improves healing in experimental rat colitis. Undersea Hyperb Med 2002;29:279–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostrowski RP, Colohan AR, Zhang JH. Mechanisms of hyperbaric oxygeninduced neuroprotection in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2005;25:554–71. doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thom SR, Milovanova TN, Yang M, et al. Vasculogenic stem cell mobilization and wound recruitment in diabetic patients: increased cell number and intracellular regulatory protein content associated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Wound Repair Regen 2011;19:149–61. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2010.00660.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimitroff CJ, Lee JY, Rafii S, et al. CD44 is a major E-selectin ligand on human hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Cell Biol 2001;153:1277–86. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.6.1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams K, Motiani K, Giridhar PV, et al. CD44 integrates signaling in normal stem cell, cancer stem cell and (pre)metastatic niches. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2013;238:324–38. doi:10.1177/1535370213480714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ditschkowski M, Einsele H, Schwerdtfeger R, et al. Improvement of inflammatory bowel disease after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation 2003;75:1745–7. doi:10.1097/01.TP.0000062540.29757.E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan M, Meduru S, Gogna R, et al. Oxygen cycling in conjunction with stem cell transplantation induces NOS3 expression leading to attenuation of fibrosis and improved cardiac function. Cardiovasc Res 2012;93:89–99. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvr277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prockop DJ, Oh JY. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs): role as guardians of inflammation. Mol Ther 2012;20:14–20. doi:10.1038/mt.2011.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fromont Hankard G, Cezard JP, Aigrain Y, et al. CD44 variant expression in inflammatory colonic mucosa is not disease specific but associated with increased crypt cell proliferation. Histopathology 1998;32:317–21. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brismar K, Lind F, Kratz G. Dose-dependent hyperbaric oxygen stimulation of human fibroblast proliferation. Wound Repair Regen 1997;5:147–50. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475X.1997.50206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simsek K, Ay H, Topal T, et al. Long-term exposure to repetitive hyperbaric oxygen results in cumulative oxidative stress in rat lung tissue. Inhal Toxicol 2011;23:166–72. doi:10.3109/08958378.2011.558528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee LC, Lieu FK, Chen YH, et al. Tension pneumocephalus as a complication of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in a patient with chronic traumatic brain injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2012;91:528–32. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31824ad556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seckin M, Gurgor N, Beckmann YY, et al. Focal status epilepticus induced by hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Neurologist 2011;17:31–3. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181d2a933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hulagu S, Demirturk L, Ozel M, et al. Therapeutic experience of hyperbaric oxygenation in ulcerative colitis refractory to medicaltreatment (Case report). Turk J Gastroenterol 1997;8:109–11. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuroki K, Masuda A, Uehara H, et al. A new treatment for toxic megacolon. Lancet 1998;352:782 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)95043-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frawley GP, Fock A. Pediatric hyperbaric oxygen therapy in Victoria, 1998–2010. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012;13:e240–4. doi:10.1097/PCC.0b013e318238b3f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gürbüz AK, Elbüken E, Yazgan Y, et al. A different therapeutic approach in patients with severe ulcerative colitis: hyperbaric oxygen treatment. South Med J 2003;96:632–3. doi:10.1097/01.SMJ.0000074507.31006.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karkŭmov M, Nikolov N, Georgiev L, et al. Hyperbaric oxygenation as a part of the treatment of chronic ulcerohemorrhagic colitis. Vutr Boles 1991;30:78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchman AL, Fife C, Torres C, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for severe ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001;33:337–9. doi:10.1097/00004836-200110000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chuck AW, Hailey D, Jacobs P, et al. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot ulcers. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2008;24:178–83. doi:10.1017/S0266462308080252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamada S, Yoshino T, Matsuura M, et al. Long-term efficacy of infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis: results from a single center experience. BMC Gastroenterol 2014;14:80 doi:10.1186/1471-230X-14-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]