Abstract

Background:

Pharmacy students can help protect the public from vaccine-preventable diseases by participating in immunization initiatives, which currently exist in some Canadian and American jurisdictions. The objective of this article is to critically review evidence of student impact on public health through their participation in vaccination efforts.

Methods:

PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Database, EMBASE, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, Scopus and Web of Science electronic databases were searched for peer-reviewed literature on pharmacy student involvement in vaccination programs and their impact on public health. Papers were included up to November 17, 2015. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and extracted data from eligible full-text articles.

Results:

Eighteen titles met all inclusion criteria. All studies were published between 2000 and 2015, with the majority conducted in the United States (n = 12). The number of vaccine doses administered by students in community-based clinics ranged from 109 to 15,000. Increases in vaccination rates in inpatient facilities ranged from 18.5% to 68%. Across studies, student-led educational interventions improved patient knowledge of vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases. Patient satisfaction with student immunization services was consistently very high.

Discussion:

Methodology varied considerably across studies. The literature suggests that pharmacy students can improve public health by 1) increasing the number of vaccine doses administered, 2) increasing vaccination rates, 3) increasing capacity of existing vaccination efforts, 4) providing education about vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases and 5) providing positive immunization experiences.

Conclusion:

Opportunities exist across Canada to increase pharmacy student involvement in immunization efforts and to assess the impact of their participation. Greater student involvement in immunization initiatives could boost immunization rates and help protect Canadians from vaccine-preventable diseases.

Knowledge into Practice.

Student-led immunization efforts have been reported in the United States and in several Canadian provinces. When pharmacy students are permitted to administer vaccines, this provides a valuable opportunity to practise injection administration, develop patient assessment skills and assist in public immunization efforts. In some jurisdictions, students are involved in screening and education about vaccinations.

This study provides a critical review of peer-reviewed literature addressing the public health impact of pharmacy students’ involvement in immunization initiatives. In addition to improving immunization efforts, pharmacy student participation has the potential to increase vaccination rates, improve patient knowledge about vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases and provide patients with a positive immunization experience.

As immunization authority for pharmacists expands across Canada, opportunities exist to increase students’ scope of practice to public immunization efforts, measure the impact of student participation and enhance students’ education.

Mise En Pratique Des Connaissances.

Des activités de vaccination dirigées par des étudiants ont eu lieu aux États-Unis et dans plusieurs provinces canadiennes. Lorsqu’on autorise les étudiants en pharmacie à administrer des vaccins, on leur donne une occasion précieuse de s’entraîner à l’administration des injections, de perfectionner leurs aptitudes d’évaluation des patients et de contribuer aux efforts de vaccination publique. Dans d’autres administrations, les étudiants participent au dépistage et à l’éducation sur les vaccinations.

Cette étude offre une analyse critique de la documentation évaluée par les pairs portant sur les effets sur la santé de la participation des étudiants en pharmacie aux initiatives de vaccination. En plus d’améliorer les activités d’immunisation, la participation des étudiants en pharmacie peut accroître les taux de vaccination, améliorer les connaissances des patients sur les vaccins et les maladies évitables par la vaccination et offrir aux patients une expérience positive lors de leurs vaccinations.

Les pharmaciens obtiennent de plus en plus de pouvoirs en matière de vaccination dans l’ensemble du Canada, ce qui représente une excellente occasion d’élargir le champ d’exercice des étudiants aux activités d’immunisation publique, de mesurer l’effet de la participation des étudiants et de renforcer la formation des étudiants.

Introduction

Vaccine-preventable diseases inflict a significant burden on Canadians and the health care system. Over 2014–15, 7784 hospitalizations and 597 deaths were attributed to influenza alone.1 Each year, some 1000 to 3000 Canadians fall ill from pertussis,2 and although Canada has been free of endemic measles since 1998,3 in 2011 the number of confirmed cases of measles reached 752.3 These outbreaks, as well as recent cases of hepatitis A,4 have been attributed to travellers’ importing disease from countries with disease activity and then infecting unimmunized or underimmunized individuals.4 Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease have been described as “a warning against complacency over vaccination programs.”5

For all vaccine-preventable diseases, immunization is the most effective method of prevention.6,7 However, the availability of a vaccine does not necessarily guarantee access and uptake. Vaccination rates in the general adult population in Canada have been below 50% for tetanus since 2006, below 40% for influenza since 2001 and below 10% for pertussis since 2006.8

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has identified several contributors to poor vaccination rates in adulthood, among them a lack of recognition of the importance of adult immunization, a lack of recommendation from health care providers, a lack of health care provider knowledge about adult immunization and recommended vaccines, misrepresentation/misunderstanding of the risks of vaccination and benefits of disease prevention in adults and missed opportunities for vaccination.9 PHAC states that “health care providers have a responsibility to ensure that adults under their care have continuing and updated protection against vaccine-preventable diseases through appropriate immunization.”9

The role of pharmacists

As practitioners on the front lines of patient care, pharmacists are in an ideal position to address these barriers. They can begin conversations with patients about immunization, provide vaccine and disease education and make recommendations. In a number of jurisdictions, pharmacists can administer vaccines, provided they complete approved injection training and certification.10 Pharmacists in some states in the United States have been authorized to immunize since the 1990s, and this authorization has been associated with higher immunization rates in the respective states.11,12 In addition, patients tend to take advantage of opportunities to be vaccinated at times of the day that are outside of physicians’ office or clinic operating hours.13

The role of pharmacy students

A number of jurisdictions in the United States and Canada permit pharmacy students to administer a variety of vaccines as long as students are registered with their respective pharmacy licensing authority, have completed the approved injection-training program for their jurisdiction and are supervised by an injection-certified pharmacist or other health care professional.10 In addition to protecting patients against disease, permission to immunize provides students a valuable opportunity to apply their knowledge and skills outside the classroom and to further refine them before graduation.

Can pharmacy students have an impact on public health when they are involved in immunization initiatives? It is important to answer this question because Ontario, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island in Canada and Alaska, Massachusetts and New Hampshire in the United States have not extended permission to administer immunizations to pharmacy students.10 The lack of authority to immunize as a student, before being registered as a pharmacist, results in a possible 2-year gap between receiving the training and having the ability to administer vaccinations. This gap between training and practice is not experienced by nursing students. Extending immunization authority to pharmacy students will not only benefit students but can also potentially help improve national vaccination rates.

The objective of this article is to summarize current evidence of the impact of pharmacy students on public health when they are involved in immunization initiatives and to address the perspectives of patients receiving this care.

Methods

In consultation with a librarian, the second author (S.J.) conducted a systematic search of peer-reviewed literature on January 26, 2014, as part of a student independent study project. The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Cochrane Database, EMBASE, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA), Scopus and Web of Science. Search terms included (“pharmacy student*” OR “student pharm*”) AND (immuniz* OR vaccin* OR “flu shot” OR influenza). Specific search terms for flu shot and influenza were used to capture titles focusing on influenza that may not have had “vaccine” in their title. Literature searches were not restricted by publication date or geography, but only articles published in English were included.

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts identified in the search for inclusion or exclusion. Titles were included if they were a full-text article published in a peer-reviewed journal, if they mentioned pharmacy students and an immunization initiative and if there was an evaluative component or outcome (e.g., patient screening, number of vaccines administered, patient satisfaction and patient knowledge). Titles were excluded if they were a conference abstract or gray literature, if they were published in a language other than English, if there was no evaluative outcome or if measures were limited to student outcomes (e.g., learning and/or confidence). The 2 reviewers achieved 86% (71/83) agreement for included titles, and differences were discussed until consensus was reached. The reference sections of eligible studies were also searched manually for additional full-text articles not identified by the electronic database search.

The search was updated on November 17, 2015, using the same databases and search terms. One author screened titles using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as those of the original search, excluded all titles identified in the original search and manually searched the reference sections of newly identified articles.

Data extraction was performed by 2 authors and independently verified by a third author. Data were collected descriptively.

Results

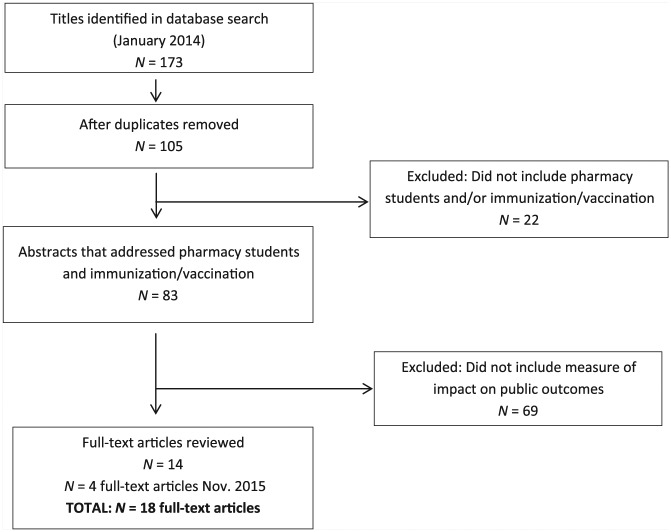

The original search in January 2014 resulted in 173 titles, of which 14 met all our inclusion criteria. The search in November 2015 yielded 4 additional titles14-17 that met all our inclusion criteria, for a grand total of 18 full-text articles for review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process

Of the 18 studies, 15 were conducted in the United States and 3 in Canada. All articles were published between 2000 and 2015. Vaccines addressed in these articles included influenza (n = 10), pneumococcal (n = 5), Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis) (n = 3), hepatitis B (n = 1), herpes zoster (n = 3) and H1N1 (n = 1) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies that address pharmacy student involvement in immunization initiatives and their impact on public health outcomes

| Article | Year study conducted | Vaccine(s) | Setting | No. | Student intervention | Reported vaccina-tion rate at baseline | Reported vaccination rate post-intervention (difference) | Reported no. of student-administered vaccinations | Patient survey included? | If yes, general survey results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banh (2012)18 | 2010 | Influenza | University influenza campaign (2 days, 3 campuses) | 50 students | Student-admini-stered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | 330 | N/A | N/A |

| Banh and Cor (2014)14 | 2012 | Influenza | University influenza campaign (October and November) | 86 students; 1314 surveys analyzed | Student-admini-stered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | Between 3699 and 1314 (Both nursing students and pharmacy students administered vaccines. Survey administered only to those vaccinated by pharmacy students; 1314 surveys completed.) |

Patient satisfaction survey after receiving vaccination | 99% reported the student service was very good or excellent 97% agreed or strongly agreed they were willing to receive vaccines from a pharmacist in the future |

| Cheung et al. (2013)19 | 2011 | Influenza | University influenza campaign (6 days, 3 campuses) | 80 students; 1555 surveys analyzed | Student-administered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | 4589 (Number includes vaccines administered by pharmacy students and nursing students. Total number vaccinated by pharmacy students not reported.) |

Patient satisfaction survey after receiving vaccination | 99% were satisfied or very satisfied with service 92% agreed or strongly agreed they would willingly receive vaccinations from community pharmacist 98% rated their overall experience as very good or excellent |

| Chou et al. (2014)20 | 2012 | Influenza, Tdap | University, middle school, health fair, community pharmacy immunization clinics (9 months, 8 sites) | 17 students; 207 interventions; 198 completed surveys | 5-minute student-led patient consulta-tions; student-admini-stered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | 109 (influenza = 68; Tdap = 41) |

Vaccine knowledge and attitudes (pre- and postinter-vention) |

Significant improvement in scores postintervention 93.5% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the student-led intervention was educational |

| Clarke et al. (2013)21 | 2008–9 (baseline); 2009–10 (intervention) | Tdap | Hospital (postpartum unit) | 17 students; 1263 patient consultations | Student-led patient counselling: verbal and written information provided | 43.7% | 62.3% (+18.5%, p < 0.001)* | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Conway et al. (2013)22 | 2010, 2011 | Influenza | University influenza clinic (2 campuses; 2010: 57 clinic hours; 2011: 65 clinic hours) | 2010: 39 students; 1596 surveys 2011: 58 students; 1166 surveys |

Student-administered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | 2010: 2292 2011: 2877 |

Patients’ feedback on vaccinator’s skill level | 2010: 97% rated vaccinator’s skills as good or excellent 2011: Over 95% reported they were very satisfied with receiving the vaccination |

| Dang et al. (2012)23 | 2010 | Influenza | Election Day influenza immunization clinic (6 hours, 1 site) | 12 students | Student-administered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | 153 | Brief exit survey to assess patients’ experience and satisfaction with vaccination | Patient experience survey results reflected general satisfaction among those who were vaccinated. |

| Dodds et al. (2001)24 | 1999–2000 (7 months) | Pneumococcal | 4 hospitals | 28 students; 785 screened patients |

Student-led screening for patients’ vaccine eligibility | 38% (at hospital admission) |

57% (at discharge) (+19%)* |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Galal et al. (2014)15 | 2007–12 (immunizations in 2010–12 only) | 2010: Influenza; 2011, 2012: Influenza, pneumococcal, herpes zoster | Community outreach events 2010: 9 events, 764.5 hours 2011: 13 events, 1619 hours 2012: 12 events, 2383 hours |

2010: 33 students 2011: 40 students 2012: 42 students |

Student-administered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | 2010: 208 (influenza) 2011: 429 (influenza, pneumococcal, herpes zoster) 2012: 583 (influenza, pneumococcal, herpes zoster) |

N/A | N/A |

| Hak et al. (2000)25 | 1998, 1999 | Influenza | University influenza campaign (1 day each year) | 1998: 66 students; 1999: 64 students | Student-administered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | 1998: 1250 1999: 1248 |

N/A | N/A |

| Lam (2005)26 | Not indicated | Influenza | Assisted-living facility | 24 students; 118 patients | Student-administered vaccinations as part of patient medication reviews | 0% | 68% (?)† | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Miller et al. (2012)27 | 2009–10 (6 months) | H1N1 | 18 Community Pharmacy Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (CP-APPE) sites | 19 students; 215 patients | Standardized, student-administered patient education | N/A | N/A | N/A | Patient knowledge of H1N1, comfort with pharmacists as immunizers (pre- and postinter-vention) |

Patient knowledge of H1N1 improved significantly after intervention. Significant increase in number of patients comfortable receiving H1N1 vaccine from pharmacists (69% to 81%, p < 0.05). |

| Mobley et al. (2004)28 | 2001-02 (15 months) | Not specified | Not specified | 2001 and 2002 combined: 64 students 2001: 265 patient surveys 2002: 210 patient surveys |

Student presentation and patient counselling (Education focused mainly on medications but included immuniza-tion.) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | Patient satisfaction with student-provided education (postinter-vention only; modified survey in 2002) |

96.6% of patients agreed with the statement: “Helped me to understand the importance of receiving my immunizations.” |

| Ouyang et al. (2013)29 | 2011–12 (7 months) | Hepatitis B | 2 student-led hepatitis B virus screening and vaccination clinics (held twice monthly) |

52 patients completed all 3 surveys Number of students not specified (Student educators included pharmacy, nursing and medical students. The number of each type of student who participated not reported.) |

Scripted, student-led education sessions | N/A | N/A | N/A | Patient knowledge scores (pre- and postinter- vention) |

Mean knowledge scores improved from 56% at baseline to 67% after the session, to 68% after 1 month. There was a statistically significant difference between the first and second and first and third tests. |

| Skledar et al. (2007)30 | 2003 (baseline); 2004–5 (intervention) | Pneumococcal | Academic teaching hospital | 7 students; on average, 800 patients screened per month | Student-led patient counselling and screening for vaccine eligibility | 38% | 70% (+32%)* | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Teeter et al. (2014)16 | 2013 | Herpes zoster | Community pharmacies | 100 students 500 patients |

Scripted, student-led education sessions | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | Post intervention: 72.5% of unvaccinated patients reported they were interested in speaking with their pharmacist or physician about receiving the herpes zoster vaccine |

| Turner et al. (2007)31 | 2004, 2005 | Influenza, pneumococcal, other adult vaccines (not specified) | Community pharmacy immunization clinic (2 sites, 3 months each year) | 2004: 121 students 2005: 123 students |

Student-administered vaccinations | N/A | N/A | 2004: 5000 2005: 15,000 (Numbers are based on student and preceptor estimates.) |

N/A | N/A |

| Zorek et al. (2015)17 | ? | Pneumococcal, herpes zoster, tetanus | Interprofessional teaching clinic (one-half day per week, maximum 3 eligible patients per day) | Number of students not provided 33 patients |

Student-led screening for vaccine eligibility | Pneumo-coccal: 21 up-to-date out of 33 screened (64%) Zoster: 12 up-to-date out of 33 screened (36%) Tetanus: 17 up-to-date out of 33 screened (52%) |

Pneumo-coccal: 28 up-to-date out of 33 screened (85%) (+21%)* Zoster: 16 up-to-date out of 33 screened (49%) (+13%)* Tetanus: 20 up-to-date out of 33 screened (61%) (+9%)* |

N/A | Yes, but not specific to immunization | N/A |

N/A, not available; Tdap, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis.

Vaccines were administered by other certified health care professionals.

Author reported a baseline vaccination rate of 0% but stated documentation was lacking to determine whether patients were vaccinated previously by other health care providers at baseline. Thus, the difference in vaccination rate cannot be determined.

Articles were categorized according to how the public health outcomes of pharmacy students’ involvement with immunizations were measured, as follows: 1) the number of vaccinations administered by students within a defined period (e.g., during clinic hours), 2) students’ impact on vaccination rates, 3) patients’ satisfaction with receiving immunization from a student and 4) the effect of student-led initiatives on patient knowledge regarding vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases.

Student impact measured by number of vaccines administered

Eight studies reported the number of vaccine doses administered by pharmacy students14,18-20,22,23,25,31 (Table 1). The number of vaccinations administered varied widely, from 10920 to 15,000.31 Immunizations reported in these studies took place in clinics or during university/college immunization drives and varied considerably in the number of sites, length of time the immunization services were available and the number of student vaccinators. For example, in Chou et al.’s study,20 vaccinations were offered at 8 sites over 9 months with 17 student vaccinators, whereas in Banh’s18 study, 330 student-administered vaccinations took place at 3 sites over 2 days, involving 50 student vaccinators. Cheung et al.19 and Turner et al.31 reported high numbers of student-administered vaccinations: 4589 vaccinations by the former,19 and 5000 and 15,000 by the latter.31 However, Cheung et al. noted that their study’s total included vaccinations administered by nursing students,19 while Turner et al.’s figures were based on student and preceptor estimates of the number of vaccines administered.31 Banh and Cor reported that students, which included both pharmacy and nursing, administered 3699 doses of influenza vaccine during their university campus influenza drive. In this study, only patients who were vaccinated by pharmacy students were offered an opportunity to complete a satisfaction questionnaire, and since they received 1314 completed questionnaires, this is the minimum number of doses that were administered by pharmacy students during their clinic.14

In 3 instances, the numbers of student-administered vaccinations were reported for 2 consecutive flu seasons. Hak et al.’s study totals revealed no change in numbers from year 1 to year 2,25 whereas Conway et al. and Turner et al. reported increases of 58522 and 10,00031 vaccinations, respectively (Table 1). As previously mentioned, Turner et al.’s numbers are based on estimates. Galal et al. provide the number of student-administered vaccinations for 3 consecutive years: in 2010, students administered 208 influenza vaccinations; in 2011, students administered 429 vaccinations; and in 2012, the number rose to 583 vaccinations.15 The last 2 years included pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccines as well as influenza vaccine; however, a breakdown of the number of administered vaccines by type is not provided.

Both Cheung et al. and Chou et al. reported that roughly a third of patients who received their influenza vaccine from students had not been immunized in the previous year.19,20 Dang et al. noted that 42 of the 153 patients at the student-run clinic received the influenza vaccine for the first time.23

Student impact measured by effect on vaccination rate

Change in vaccination rates from pharmacy student participation in vaccination programs was reported in 5 articles (Table 1).17,21,24,26,30 These studies took place in a hospital, teaching clinic or an assisted-living facility. Pharmacy students administered vaccines in only 1 intervention.26 In the other 4 studies, pharmacy students screened patients for vaccine eligibility, and vaccinations were administered by a nurse or other certified health professional.

All 5 studies reported an increase in inpatient vaccination rates as a result of pharmacy student involvement in vaccination services (Table 1).17,21,24,26,30 Vaccination rates increased between 9% and 68%. Clarke et al. reported that the increase—18.5% in this study—was statistically significant.21 Zorek et al. indicated that vaccination rates increased for pneumococcal, herpes zoster and tetanus vaccines following their patient screening program; however, the only statistically significant increase in rate was seen with the pneumococcal vaccine.17

Dodds et al.24 and Skledar et al.30 found that students spent an average of 5 minutes to complete patient screening. Dodds et al. found that time spent ranged from 1 to 30 minutes, depending on the completeness and availability of patient medical records and whether the screening included a patient interview,24 whereas Skledar et al. found that with 7 pharmacy students screening patient records for vaccine eligibility (patient education was conducted by nurses), an average of 33 patients were screened daily.30

Student impact measured by patients’ satisfaction

Five studies measured patients’ satisfaction after a vaccine was administered by a pharmacy student14,19,22,23,28 (Table 1). Four studies involved students administering influenza vaccinations during a campus influenza immunization drive or a community clinic.14,19,22,23 The setting was not specified in Mobley et al.’s study.28

Patients’ satisfaction with pharmacy students’ involvement in immunization initiatives was consistently positive. Banh and Cor,14 Cheung et al.19 and Conway et al.22 found that over 90% of survey participants were satisfied or very satisfied with the student-led immunization service. Conway et al., who report data from a university immunization clinic, found that 75% of their patients who were surveyed were “repeat customers” from the vaccination clinic held the previous year, and approximately one-third of the vaccine recipients were health care providers and skilled vaccinators themselves.22 Banh and Cor found that, based on their experience with student immunizers, 97% of survey respondents were willing to receive vaccines from a pharmacist in the future.14

Student impact measured by patient knowledge

Five studies measured the effect of a pharmacy student intervention on patient knowledge about vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases16,20,27-29 (Table 1). Mobley et al. surveyed patients after they attended a student presentation and received patient counselling regarding vaccines, of which 96.6% reported a new understanding of the importance of receiving vaccinations.28 Teeter et al. also surveyed patients after a student-led educational initiative and found that most unvaccinated patients (72.5%) were interested in speaking with their pharmacist or doctor about receiving the herpes zoster vaccine, following information provided by the student.16 Unfortunately, no data were reported on the number of patients who followed through on their intentions.

The remaining studies measured a number of variables before and after a standardized student-led education session.20,27,29 Despite heterogeneity across studies in the content of educational sessions and items on patient surveys, all authors reported improved patient knowledge after education sessions provided by pharmacy students. Chou et al. also noted a statistically significant improvement in patients’ attitude toward vaccinations,20 and Miller et al. cited significant improvement in patients’ comfort level in receiving a vaccine.27 Ouyang et al. found that patients’ knowledge scores remained significantly higher than did their baseline scores 1 month after their student-led education session.29 Chou et al. demonstrated that patients’ increased knowledge about vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases was related to their seeking and obtaining vaccinations.20

Discussion

Pharmacy students, who will become future practitioners and provide patient care services, share the responsibility with other health care professionals for improving public health. They have an important role to play in educating the public about vaccinations, advocating for vaccinations and vaccinating their patients. Pharmacy students in many jurisdictions have been involved in vaccination efforts for some time,10 but their impact on disease prevention and improving public health has not been explored extensively.

Pharmacy student impact on vaccination coverage

Authors who reported the number of vaccinations administered by students did not provide comparative groups or context for their findings. Although several studies found increases in the number of vaccines administered over time, true control groups and statistical analyses were largely absent. Only 2 articles reported a statistically significant increase in vaccination rates after a student intervention17,21; thus, the impact that pharmacy students have on vaccination rates and the number of vaccinations administered remains unclear.

Some studies provided evidence that students were immunizing repeat patients as well as first-time patients,19,22,23 who might not have otherwise received protection from vaccine-preventable illness were it not for the student service. Moreover, even if they do not participate directly in vaccination administration, pharmacy students may still help increase vaccination rates by participating in patient screening,21,24,30 a role that can be a valuable experience for students who are not permitted to administer immunizations and that does not require changes to legislation.

Pharmacy student impact on patient education and follow-up

Studies that evaluated the impact of pharmacy students on patient knowledge varied in their methods.20,27-29 Each research study used a different patient knowledge assessment tool, and measures of validity and reliability were absent. Regardless of the method and content of assessment, the literature indicates a consistent positive impact of pharmacy students on patient knowledge about vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases,20,27-29 although none reported whether student-led educational interventions led to actual patient vaccinations.

While pharmacy students were screening patients for vaccine eligibility, they were also potentially playing the role of patient educator. In fact, Clarke et al. included student-led patient counselling as part of the patient-screening process.21 It will be important to clarify whether the inclusion of patient education in the screening process ultimately results in more vaccinations, rather than simply increasing interest in receiving vaccinations.16

Ouyang et al.’s study noted that pharmacy students screened patients for their eligibility for the hepatitis B vaccine and informed the patients of the importance of completing the 3-dose series; however, the article did not discuss follow-up efforts with vaccine-eligible patients to determine if all 3 vaccinations were administered.29

The educational interventions used across studies appeared simple and brief and thus have the potential to be incorporated easily into pharmacist- or pharmacy student‒patient educational interactions.

Pharmacy student impact on patient satisfaction

Over 90% of immunized patients in each study reported that they were highly satisfied with the student service or rated their experience as excellent.14,19,20,22,23,28 In the study by Cheung et al., more than 90% of patients reported that they would seek future vaccinations from a community pharmacist, based on their experience with student vaccinators.19

Few details were given regarding the administration of patient satisfaction surveys, specifically if they were administered by the same pharmacy students who gave the interventions and/or vaccinations; thus, these surveys might suffer from a positive response bias. Ratings of satisfaction might have been inflated by patients in an attempt to help the students succeed in their program. Survey administration by a third party would help to lower potential positive response bias. Also absent are reports of survey pilot tests and measures of validity and reliability. Finally, selection bias is present given that participants chose to receive their immunization from a pharmacist.

Pharmacy student impact on capacity building

Several authors noted that pharmacy students can increase the capacity of existing immunization efforts. For example, Banh18 reported that including pharmacy student immunizers in the university influenza campaign allowed the campaign to be expanded to additional campuses.28 Similarly, Conway et al. found that without the participation of pharmacy students, the campus influenza clinics would have been discontinued by the original provider because of budget cuts.22

Limitations of the reviewed research

Two areas received little discussion. First, Hak and colleagues were the only authors to mention harm outcomes, such as needle stick injuries, although none occurred in their study.25 No mention was made of other adverse patient or pharmacy student consequences of immunization initiatives, such as breach of sterile procedures. Moreover, even though they are supervised by an immunization-certified pharmacist, pharmacy students are using a new and little-practiced skill set. These areas warrant monitoring and future research.

Second, Operation Immunization—a college campus‒based immunization initiative across the United States that has immunized more than 1 million individuals (www.pharmacist.com/apha-asp-operation-immunization)—was not mentioned in any of the studies. Results of Operation Immunization appear on the organization’s website, in descriptive articles32,33 and in gray literature.34,35 Such a large, organized and established initiative would provide an excellent opportunity to measure the impact of student immunization services on public health and to provide students the opportunity to participate in pharmacy practice research. Currently, no similar large-scale immunization initiative exists in Canada.

Limitations of this review

Because of significant heterogeneity in study methodology and the detail to which results were reported, direct comparison of studies as well as pooling of data were not feasible. We also excluded conference abstracts and gray literature.

Conclusion

Evidence suggests that if pharmacy students are given the opportunity to participate in immunization programs, they can 1) provide additional vaccination opportunities for the public, particularly for those who might not otherwise be vaccinated; 2) provide added capacity to existing immunization efforts; and 3) educate the public regarding vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases. Research consistently shows high patient satisfaction with pharmacy student–provided immunization services. Opportunities exist in Canada to expand student participation in immunization efforts, to measure the impact students have on immunization rates and to ultimately make vaccines more accessible to Canadians.■

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Shannon Gordon, MLIS, for assistance with the literature search and Joe Petrik, MSc, MA, for editing and formatting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:D. Church screened titles and abstracts, extracted data, wrote the initial full draft of the manuscript and edited the manuscript. S. Johnson conducted the literature search and initial screening and review, developed themes and reviewed and edited the manuscript. J. Pearson Sharpe screened titles and abstracts, developed themes, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. L. Raman-Wilms reviewed articles, extracted data, provided direction to the drafting of the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. E. Schneider developed the initial research question and provided direction for review of articles and manuscript. N. Waite developed the initial research question, provided direction for review of articles and manuscript and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding:This research results from an Applied Health Research Question (AHRQ) submitted by the Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA) to the Ontario Pharmacy Research Collaboration (OPEN) (www.open-pharmacy-research.ca/research-projects/ahrq/ontario-pharmacy-students-as-immunizers). OPEN is funded primarily by a grant from the Government of Ontario. CPhA was interested in understanding the scope and impact of pharmacy student-administered vaccines to assist in planning immunization services. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funder or AHRQ sponsor.

References

- 1. Public Health Agency of Canada. Reported influenza hospitalizations and deaths in Canada: 2009-10 to 2014-15 (data to February 28, 2015). 2015. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/influenza/flu-stat-eng.php (accessed Mar. 11, 2015).

- 2. Public Health Agency of Canada. Pertussis (whooping cough). 2014. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/vpd-mev/pertussis-eng.php (accessed Jun. 3, 2015).

- 3. Public Health Agency of Canada. Guidelines for the prevention and control of measles outbreaks in Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep 2013;39:1-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kwong JC, Crowcroft NS, Campitelli MA, et al. Ontario Burden of Infectious Disease Study Advisory Group. Ontario Burden of Infectious Disease Study (ONBOIDS): An OAHPP/ICES report. Toronto (ON): Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deeks SL, Lim GH, Simpson MA, et al. An assessment of mumps vaccine effectiveness by dose during an outbreak in Canada. CMAJ 2011;183:1014-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Public Health Agency of Canada. Immunization and vaccines. 2015. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/index-eng.php (accessed Jul. 1, 2015).

- 7. Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Reportable disease trends in Ontario, 2012. Toronto (ON): Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Public Health Agency of Canada. Vaccine coverage amongst adult Canadians: results from the 2012 adult National Immunization Coverage (aNIC) survey. 2014. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/nics-enva/vcac-cvac-eng.php (accessed Jun. 18, 2015).

- 9. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian immunization guide. Part 3: vaccination of specific populations. 2013. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cig-gci/p03-02-eng.php (accessed Jun. 8, 2015).

- 10. Johnson S, Waite N, Schneider E. Pharmacy students as immunizers: review and policy recommendations. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2014;147:s10. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grabenstein JD, Guess HA, Hartzema AG, et al. Effect of vaccination by community pharmacists among adult prescription recipients. Med Care 2001;39:340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steyer TE, Ragucci KR, Pearson WS, Mainous AG., III The role of pharmacists in the delivery of influenza vaccinations. Vaccine 2004;22:1001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goad JA, Taitel MS, Fensterheim LE, Cannon AE. Vaccinations administered during off-clinic hours at a national community pharmacy: implications for increasing patient access and convenience. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:429-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Banh HL, Cor K. Evaluation of an injection training and certification program for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ 2014;78(4):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galal SM, Carr-Lopez SM, Gomez S, et al. A collaborative approach to combining service, teaching and research. Am J Pharm Educ 2014;78:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Teeter BS, Garza KB, Stevenson TL, et al. Factors associated with herpes zoster vaccination status and acceptance of vaccine recommendation in community pharmacies. Vaccine 2014;32:5749-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zorek JA, Subash M, Fike DS, et al. Impact of an interprofessional teaching clinic on preventive care services. Fam Med 2015;47:558-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Banh HL. Alberta pharmacy students administer vaccinations in the University Annual Influenza Campaign. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2012;145:112-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheung W, Tam K, Cheung P, Banh HL. Satisfaction with student pharmacists administering vaccinations in the University of Alberta annual influenza campaign. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2013;146:227-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chou TI, Lash DB, Malcolm B, et al. Effects of a student pharmacist consultation on patient knowledge and attitudes about vaccines. J Am Pharm Assoc 2014;54:130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clarke C, Wall GC, Soltis DA. An introductory pharmacy practice experience to improve pertussis immunization rates in mothers of newborns. Am J Pharm Educ 2013;77:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conway SE, Johnson EJ, Hagemann TM. Introductory and advanced pharmacy practice experiences within campus-based influenza clinics. Am J Pharm Educ 2013;77:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dang CJ, Dudley JE, Truong H, et al. Planning and implementation of a student-led immunization clinic. Am J Pharm Educ 2012;76(5):78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dodds ES, Drew RH, Byron May D, et al. Impact of a pharmacy student-based inpatient pneumococcal vaccination program. Am J Pharm Educ 2001;65:258-60. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hak EB, Foster SL, McColl MP, Bradberry JC. Evaluation of student performance in an immunization continuing education certificate program incorporated in a pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ 2000;64:184-7. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lam A. Senior care clerkship: an innovative collaboration of pharmaceutical care and learning. Consult Pharm 2005;20:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miller S, Patel N, Vadala T, et al. Defining the pharmacist role in the pandemic outbreak of novel H1N1 influenza. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2012;52:763-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mobley MA, Koronkowski MJ, Peterson NM. Enhancing student learning through integrating community-based geriatric education outreach into ambulatory care advanced practice experiential training. Am J Pharm Edu 2004;68:20. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ouyang D, Yuan N, Sheu L, et al. Community health education at student-run clinics leads to sustained improvement in patients’ hepatitis B knowledge. J Community Health 2013;38:471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Skledar SJ, McKaveney TP, Sokos DR, et al. Role of student pharmacist interns in hospital-based standing orders pneumococcal vaccination program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2007;47:404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Turner CJ, Ellis S, Giles J, et al. An introductory pharmacy practice experience emphasizing student-administered vaccinations. Am J Pharm Educ 2007;71(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bartell JC. Operation Immunization 2004: prevent, protect, immunize. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2005;45:521-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gray JN. A student’s story: Operation Immunization—the road to better health. Pharmacy Today (Washington DC) 2003;9:9-10. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lutz J. WSPA/pharmacy student joint venture: implementing an immunization program in a retail community pharmacy. Washington Pharmacist 1998;40:20-2. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schilke T. Operation Immunization: making an impact on preventive health care. Pharmacy students expand their activities with immunization clinics, workshops and print resources. J Pharm Soc Wisconsin 2007;Sep-Oct. [Google Scholar]