Abstract

Background

Decreased expression of cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBPC) in the heart has been implicated as a consequence of mutations in cMyBPC that lead to abnormal contractile function at the myofilament level, thereby contributing to the development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in humans. It has not been established whether increasing the levels of cMyBPC in the intact heart can improve myofilament and in vivo contractile function and attenuate maladaptive remodeling processes because of reduced levels of cMyBPC.

Methods and Results

We performed in vivo gene transfer of cMyBPC by direct injection into the myocardium of cMyBPC-deficient (cMyBPC−/−) mice, and mechanical experiments were conducted on skinned myocardium isolated from cMyBPC−/− hearts 21 days and 20 weeks after gene transfer. Cross-bridge kinetics in skinned myocardium isolated from cMyBPC−/− hearts after cMyBPC gene transfer were significantly slower compared with untreated cMyBPC−/− myocardium and were comparable to wild-type myocardium and cMyBPC−/− myocardium that was reconstituted with recombinant cMyBPC in vitro. cMyBPC content in cMyBPC−/− skinned myocardium after in vivo cMyBPC gene transfer or in vitro cMyBPC reconstitution was similar to wild-type levels. In vivo echocardiography studies of cMyBPC−/− hearts after cMyBPC gene transfer revealed improved systolic and diastolic contractile function and reductions in left ventricular wall thickness.

Conclusions

This proof-of-concept study demonstrates that gene therapy designed to increase expression of cMyBPC in the cMyBPC-deficient myocardium can improve myofilament and in vivo contractile function, suggesting that cMyBPC gene therapy may be a viable approach for treatment of cardiomyopathies because of mutations in cMyBPC.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, echocardiography, gene therapy, myocardial contraction

Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (FHC) is an inherited autosomal disease that is most commonly caused by mutations in sarcomeric protein genes. Of the 10 different sarcomeric genes identified to cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mutations in the gene encoding cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBPC) are among the most common cause of hereditary-linked hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.1–3 FHC impacts ≈1 in 500 individuals4; however, several founding mutations in cMyBPC around the world have been recently shown to affect millions of individuals from common ancestry5 who are at significantly greater risk for development of cardiac dysfunction and heart failure compared with individuals who do not carry these mutations. The mechanisms by which cMyBPC mutations cause cardiac disease are still not clear, but the few studies that have examined human tissue samples from patients carrying cMyBPC mutations have found direct evidence for decreased expression of cMyBPC in the heart,6,7 suggesting that in these patients decreased cMyBPC expression may contribute to cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy.

A causal link between decreased cMyBPC expression and cardiac dysfunction is yet to be definitively established; however, evidence from mouse models suggests that complete absence of cMyBPC in the heart (cMyBPC−/−) leads to severe contractile dysfunction and left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy,8–11 whereas a ≈25% decrease in cMyBPC expression in hearts of heterozygous cMyBPC-null mice leads to moderate mechanical dysfunction and development of milder hypertrophy than cMyBPC−/− hearts.12,13 It is thought that the molecular mechanism that impairs cardiac contractile function in cMyBPC-deficient mice is an acceleration of cross-bridge kinetics because of a loss in the inhibitory effects of cMyBPC on actomyosin interactions14–16 and decreased stability of strongly bound cross-bridges causing their premature detachment from actin.17 However, it is yet to be demonstrated that increasing the levels of cMyBPC in the intact heart can improve contractile function of hearts deficient in cMyBPC. Thus, the goal of this study was to increase the expression of cMyBPC in cMyBPC−/− hearts by transfecting the myocardium in vivo with recombinant viral vectors to determine whether restored levels of cMyBPC in the sarcomere can reverse abnormal cross-bridge behavior at the myofilament level. A secondary goal was to determine whether restored cross-bridge function can improve impaired contractile function in vivo. This proof-of-concept experiment will establish the feasibility of cMyBPC gene therapy in a mouse model of FHC and will provide an initial platform for future research that will develop the clinical application of cMyBPC gene therapy as a strategy for treatment of cMyBPC-related FHC.

Methods

An expanded Methods section is available in the online-only Data Supplement.

cMyBPC Gene Transfer

Lentiviruses encoding the full-length mouse cMyBPC (LcMyBPC) or lacking cMyBPC (vehicle, lentivirus-cytomegalovirus (LCMV) promoter only) were generated using the ViraPower Lentivirus expression system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Adult male cMyBPC−/−8 and wild-type (WT) mice (SV/129 strain, 8–26 weeks of age) were anesthetized, and a thoracotomy was performed to directly inject the myocardium with lentivirus using a syringe with a fine needle tip. All procedures involving animal care and handling were performed according to institutional guidelines set forth by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University.

In Vitro Mechanical Experiments and In Vivo Assessment of Contractile Function

Mechanical measurements of skinned multicellular ventricular myocardium isolated from cMyBPC−/− hearts 21 days and 20 weeks after gene transfer (cMyBPC or vehicle) were performed as previously described.14,15,18,19 Mechanical measurements were also performed on cMyBPC−/− skinned myocardium after reconstitution with recombinant cMyBPC to directly compare the effects of increased cMyBPC expression by in vitro and in vivo techniques. To assess the effects of cMyBPC gene transfer on in vivo cardiac contractile function and morphology, transthoracic echocardiography was performed on a separate group of cMyBPC−/− mice 21 days after cMyBPC gene transfer (cMyBPC or vehicle).

Myofibrillar Protein Content and RNA Analysis

The cMyBPC content was measured in individual skinned myocardial preparations used for mechanical experiments by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Tissue homogenates were also prepared from ventricular preparations isolated from WT, untreated cMyBPC−/−, and cMyBPC−/− mice after cMyBPC gene transfer for analysis of myofibrillar protein content and phosphorylation by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as previously described.13 The content of cMyBPC was also evaluated in ventricular homogenates isolated from hearts that underwent echocardiographic studies after cMyBPC gene transfer. Expression levels of hypertrophic marker genes after cMyBPC gene transfer were evaluated by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Fluorescence Imaging Immunohistochemistry

Immunofluorescent detection of cMyBPC was performed by confocal microscopy on skinned myocardium and whole heart sections isolated from WT, cMyBPC−/−, and virus-treated cMyBPC−/− mice 21 days after gene transfer.

Statistical Analysis

Skinned fiber mechanical data were analyzed as previously described.14,15 Comparisons of in vitro and in vivo measurements between groups were performed using a 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

Results

Myofilament Protein Expression and Phosphorylation in WT and Virus-Treated cMyBPC−/− Myocardium Used for In Vitro Mechanical Studies

The cMyBPC content of individual fibers isolated from LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− LV that were used for mechanical experiments was not different than the cMyBPC content of fibers isolated from WT LV or cMyBPC−/− fibers after in vitro reconstitution using recombinant cMyBPC (Table 1). In contrast, no cMyBPC expression was detected in skinned myocardium isolated from vehicle-treated cMyBPC−/− LV (ie, LCMV) (Figure 1). The sarcomeric localization of cMyBPC in skinned myocardium isolated from LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts and cMyBPC−/− myocardium reconstituted with cMyBPC was probed by immunohistochemistry and showed similar staining patterns to WT myocardium, suggesting that in vivo and in vitro cMyBPC reconstitution resulted in proper cMyBPC incorporation within the sarcomere (Figure 2). Myofilament protein expression and phosphorylation were assessed in myocardium isolated from the region of the viral injection site (mid-LV to apex) of WT, cMyBPC−/−, and virus-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts that were used for mechanical experiments. No significant differences in the relative abundance or phosphorylation status of myofilament proteins were detected between groups (Figure 1). As expected, cMyBPC was not detected in fibers isolated from untreated and vehicle-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts; however, fibers isolated from LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts (21 days after cMyBPC gene transfer) expressed cMyBPC at a level of 97±7% of the cMyBPC content of fibers isolated from WT hearts. Expression of cMyBPC in LcMyBPC-treated hearts was stable and was maintained at a high level (87±12% of the cMyBPC content of WT fibers) 20 weeks after gene transfer (Table 1). Expression of β-myosin heavy chain was slightly elevated in skinned myocardium isolated from untreated cMyBPC−/− hearts (16±5%; P<0.05) compared with WT myocardium and was nearly absent in myocardium isolated from LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts (4±3%; not significant) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Steady-State and Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Skinned Fibers Isolated From WT and cMyBPC−/− Hearts After Viral Treatment and In Vitro cMyBPC Reconstitution

| Total cMyBPC Content, % | Fmin, mN/mm2 | Fmax, mN/mm2 | pCa50 | nH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (5) | 100±2 | 0.67±0.10 | 19.35±1.22 | 5.78±0.01 | 4.51±0.36 |

| cMyBPC−/− (4) | 0±0* | 0.49±0.13 | 20.36±1.43 | 5.81±0.01 | 4.20±0.49 |

| cMyBPC−/−+LCMV (3) | 0±0* | 0.56±0.18 | 19.25±1.75 | 5.79±0.02 | 4.18±0.61 |

| cMyBPC−/−+LcMyBPC (21 days) (5) | 97±7 | 0.63±0.12 | 20.67±1.19 | 5.81±0.02 | 4.29±0.42 |

| cMyBPC−/−+LcMyBPC (20 weeks) (3) | 87±12 | 0.64±0.23 | 19.57±2.02 | 5.79±0.02 | 4.40±0.62 |

| cMyBPC−/−+cMyBPC (5) | 98±9 | 0.69±0.22 | 21.08±2.17 | 5.79±0.02 | 4.27±0.44 |

WT indicates wild-type; cMyBPC, cardiac myosin binding protein C; total cMyBPC (%), percent cMyBPC content in individual fibers; Fmin, Ca2+-independent force at pCa 9.0; Fmax, maximal Ca2+-activated force at pCa 4.5; pCa50, pCa required for half-maximal force generation; nH, Hill coefficient for force-pCa relationship; cMyBPC−/−+LCMV, vehicle-treated cMyBPC−/−; cMyBPC−/−+LcMyBPC, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− 21 days or 20 weeks after gene transfer; cMyBPC−/−+cMyBPC, in vitro reconstitution of cMyBPC−/− myocardium with recombinant cMyBPC.

Data are mean±SE. Skinned ventricular fibers (20–25 per group) were isolated from 3 to 5 mice per group (indicated in parentheses). All data presented for each subgroup were collected from the number of mice indicated in the left column.

Significantly different from WT, P<0.001.

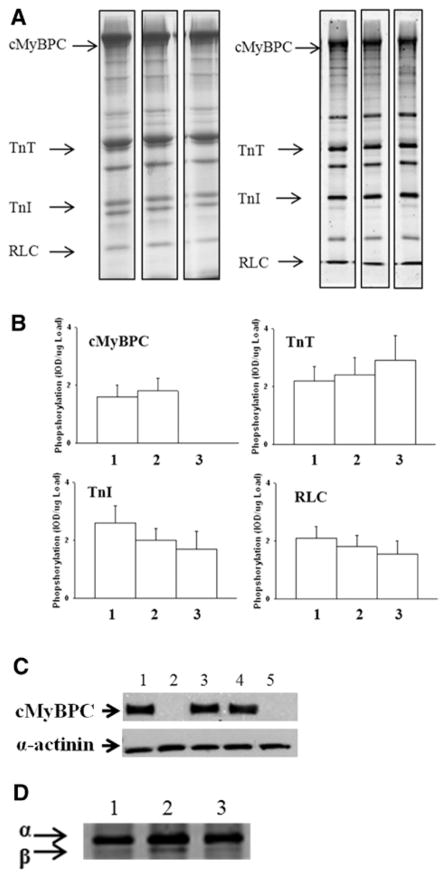

Figure 1.

Protein expression and phosphorylation in virus*treated hearts. A, Representative images of 10% SDS-PAGE Coomassie-stained (left) or 12% SDS-PAGE Pro-Q Diamond–stained gels (right) depicting protein expression in skinned myocardium isolated from wild-type (WT) (lane 1), lentiviruses encoding the full-length mouse cardiac myosin binding protein C (LcMyBPC)–treated cMyBPC−/− (lane 2), and untreated cMyBPC−/− hearts (lane 3). B, Phosphorylation analysis of Pro-Q Diamond–stained gels. Slopes of phosphorylation signals from Pro-Q Diamond–stained gels (n=4) determined from regression analysis of plots of area×average optical density vs protein loaded (μg). Myocardium was isolated from hearts of: lane 1, WT; lane 2, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/−; lane 3, cMyBPC−/− mice. Data are mean±SE. C, Western blots of skinned myocardium that was used for mechanical experiments probed with a cMyBPC-specific antibody; lane 1, WT; lane 2, cMyBPC−/−; lane 3, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− (21 days); lane 4, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− (20 weeks); lane 5, vehicle-treated cMyBPC−/−. α-Actinin was quantified as a loading control (bottom row). D, 6% SDS-PAGE silver-stained gel depicting myosin heavy chain isoform expression in myocardium isolated from: lane 1, WT; lane 2, cMyBPC−/−; lane 3, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts.

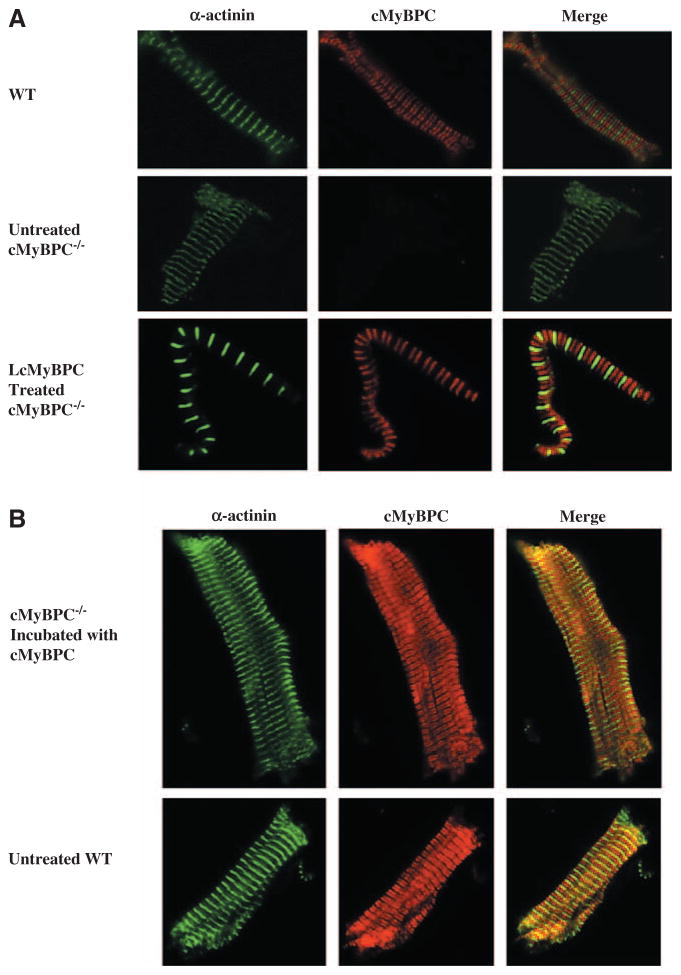

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBPC) expression in wild-type (WT), cMyBPC−/−, and lentiviruses encoding the full-length cMyBPC (LcMyBPC)–treated cMyBPC−/− myocardium. A, Confocal images (×100 magnification) of skinned myocardium isolated from WT, untreated cMyBPC−/−, and LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts. Immunohistochemistry was used to demonstrate the localization of α-actinin (green) and cMyBPC (red) within the sarcomere. B, Confocal images (×40 magnification) showing the localization of α-actinin (green) and cMyBPC (red) within the sarcomere for cMyBPC−/− skinned fibers after incubation with recombinant full-length mouse cMyBPC protein and untreated WT skinned fibers.

Mechanical Properties of Skinned Myocardium Isolated from cMyBPC−/− Hearts After In Vivo cMyBPC Gene Transfer and Reconstitution With Recombinant cMyBPC

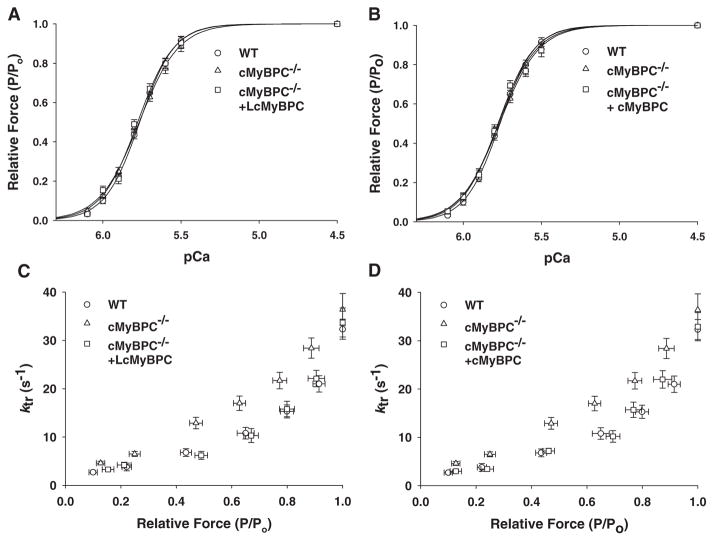

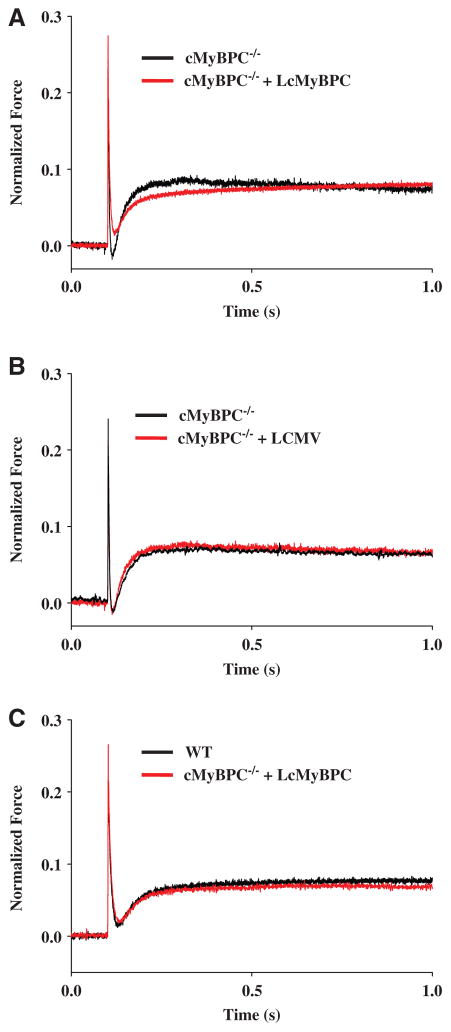

The steady-state mechanical properties of skinned myocardium isolated from WT, cMyBPC−/−, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts (21 days and 20 weeks post gene transfer), vehicle-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts, and cMyBPC−/− fibers reconstituted with recombinant cMyBPC are summarized in Table 1. Skinned myocardial preparations were isolated from the region of the viral injection site in all groups of mice. There were no differences in steady-state force generation at maximal and submaximal activating [Ca2+] or in the steepness of the force-pCa relationship (Hill coefficient, nH) in any of the groups (Figure 3). Consistent with previous studies,14,15 cMyBPC−/− skinned myocardium displayed dramatically accelerated rates of force development (ktr) (Figure 3), stretch-induced force decay (krel) and delayed force development (kdf) at submaximal Ca2+ activations, and greater stretch-induced force decay (P2 amplitude) and stretch activation amplitude (Pdf) compared with WT myocardium (Table 2). Skinned myocardium isolated from LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts displayed dramatically slower cross-bridge kinetics (ktr, krel, and kdf) compared with untreated cMyBPC−/− myocardium, both 21 days and 20 weeks after cMyBPC gene transfer (Table 2; Figures 3 and 4). In contrast, skinned myocardium isolated from LCMV-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts displayed similar stretch activation properties to untreated cMyBPC−/− myocardium (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Force-pCa and Force-ktr relationships in skinned myocardium after in vivo cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBPC) gene transfer and in vitro reconstitution with recombinant cMyBPC. Steady-state isometric force (A and B) was measured as a function of pCa, and the apparent rate constant of force development (ktr) after a rapid release-restretch protocol (C and D) was plotted as a function of relative isometric steady-state force (P/Po) in skinned myocardium isolated from wild-type (WT) (circles), untreated cMyBPC−/− (triangles), cMyBPC−/− hearts after cMyBPC gene transfer (+lentiviruses encoding the full-length cMyBPC [LcMyBPC], squares, A and C), and in vitro reconstitution of cMyBPC−/− skinned myocardium with recombinant cMyBPC (+cMyBPC, squares, B and D). Values are mean±SE of 20 to 25 experiments.

Table 2.

Stretch Activation Parameters of Skinned Fibers Isolated From WT and cMyBPC−/− Hearts After Viral Treatment

| kdf, S−1 | krel, S−1 | P2 | P3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (5) | 23.59±1.23 | 271±21 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.10±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 |

| cMyBPC−/− (4) | 35.49±1.40* | 470±20* | −0.03±0.01† | 0.10±0.01 | 0.13±0.01† |

| cMyBPC−/−+LCMV (3) | 34.96±1.92* | 443±32* | −0.04±0.02† | 0.10±0.02 | 0.14±0.02† |

| cMyBPC−/−+LcMyBPC (21 days) (5) | 24.94±1.79 | 280±27 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.11±0.01 | 0.07±0.02 |

| cMyBPC−/−+LcMyBPC (20 weeks) (3) | 26.03±2.41 | 318±36 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.11±0.02 | 0.07±0.02 |

WT indicates wild-type; cMyBPC, cardiac myosin binding protein C; cMyBPC−/−+LCMV, vehicle-treated cMyBPC−/−; cMyBPC−/−+LcMyBPC, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− 21 days or 20 weeks after gene transfer.

Data are mean±SE. Skinned ventricular fibers (20–25 per group) were isolated from 3 to 5 mice per group (indicated in parentheses). All data presented for each subgroup were collected from the number of mice indicated in the left column. Rate constants were calculated from force transients in response to stretches of 1% of muscle length at approximately half-maximal levels of activation. Stretch activation parameters are described in the online-only Data Supplement.

Significantly different from WT, P<0.001.

Significantly different from WT, P<0.01.

Figure 4.

Effects of in vivo cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBPC) gene transfer on cross-bridge kinetics. Force transients after a stretch of 1% of muscle length were recorded at [Ca2+], yielding a prestretch isometric force of ≈50% maximal in skinned myocardium isolated from (A) untreated cMyBPC−/− and lentiviruses encoding the full-length cMyBPC (LcMyBPC)–treated cMyBPC−/− hearts, (B) untreated cMyBPC−/− and LCMV-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts, and (C) wild-type (WT) and LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts. These representative transients are normalized to prestretch isometric force corresponding to the force baseline, which is arbitrarily set at zero.

The effects of increased exogenous cMyBPC content in cMyBPC−/− myocardium by in vivo gene transfer on contractile function were also directly compared with in vitro reconstitution of cMyBPC−/− myocardium with recombinant cMyBPC. Acute increases in cMyBPC content in the cMyBPC−/− sarcomere by in vivo and in vitro methods resulted in similar effects on contractile function because incubation of cMyBPC−/− skinned myocardium with recombinant cMyBPC did not alter steady-state force generation (Table 1) but dramatically slowed cross-bridge kinetics such that they became indistinguishable from WT myocardium (Figure 3).

Effects of cMyBPC Gene Transfer on In Vivo Cardiac Function

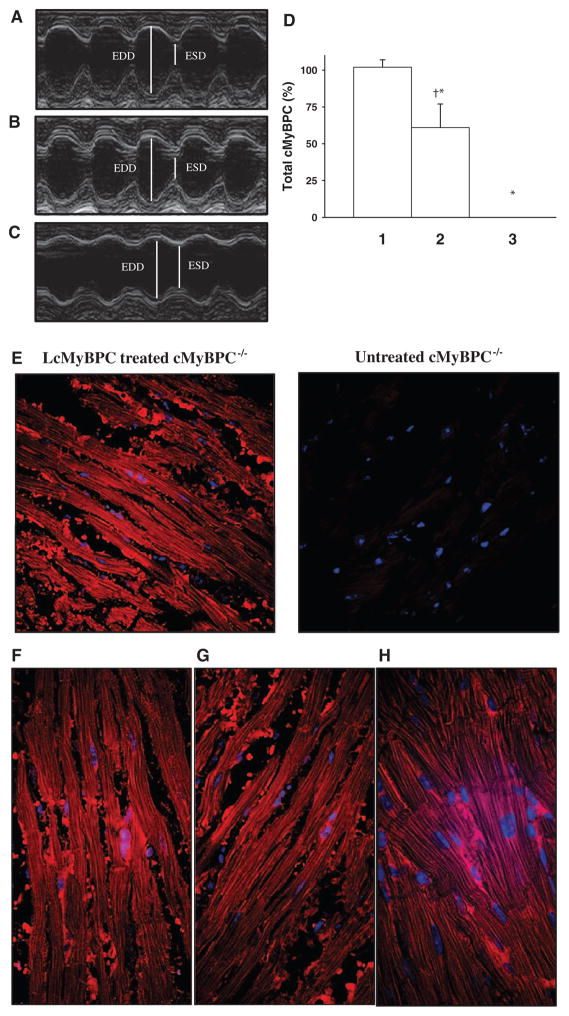

The effects of cMyBPC gene transfer on in vivo cardiac contractile function were analyzed by echocardiography in a separate group of WT, cMyBPC−/−, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− mice and are presented in Table 3. Consistent with previous findings,8–11 cMyBPC−/− hearts displayed significant increases in LV chamber dimensions at end systole and end diastole, as well as increases in posterior wall thickness and LV mass-to-bodyweight ratios, compared with WT hearts (Table 3). Furthermore, cMyBPC−/− hearts displayed diminished fractional shortening and shortened systolic ejection time and prolonged isovolumic relaxation times, indicating impaired systolic and diastolic function, respectively (Table 3). As expected, vehicle-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts showed no differences in contractile function and LV morphology compared with untreated cMyBPC−/− hearts (data not shown); however, LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts showed improvements in cardiac contractile function and reduced LV dimensions compared with untreated cMyBPC−/− hearts (Table 3; Figure 5). The effects of cMyBPC gene transfer on cMyBPC expression, in vivo cardiac contractility, and LV morphology of cMyBPC−/− hearts were variable. The average cMyBPC content of LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts assessed by in vivo echocardiography was 60±17% of the cMyBPC content of WT hearts (range, 38%–96%) (Figure 5). Hearts expressing high levels of cMyBPC displayed contractile function and LV wall dimensions that were similar to WT hearts (Figure 5), whereas hearts expressing cMyBPC at lower levels showed some functional improvements but modest changes in wall dimensions. Overall, averaged data of all LcMyBPC-treated hearts (n=19) showed statistically significant improvements in contractile function and cardiac morphology compared with untreated cMyBPC−/− hearts (Table 3).

Table 3.

In Vivo Echocardiography Summary Data From WT and cMyBPC−/− Mice

| WT | cMyBPC−/− | cMyBPC−/−+ LcMyBPC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of mice | 14 | 14 | 19 |

| BW, g | 31.13±2.30 | 29.89±0.33 | 30.03±1.37 |

| HR, beats per minute | 435±8 | 443±7 | 433±13 |

| PWTd, mm | 0.86±0.03 | 1.15±0.03* | 1.01±0.05†‡ |

| PWTs, mm | 1.26±0.03 | 1.52±0.05§ | 1.39±0.06† |

| EDD, mm | 3.47±0.12 | 4.50±0.10§ | 3.90±0.20† |

| ESD, mm | 1.65±0.11 | 3.10±0.08* | 2.19±0.17†‡ |

| LVM/BM, mg/g | 3.28±0.19 | 6.54±0.23* | 4.74±0.62§|| |

| FS | 0.52±0.02 | 0.31±0.02* | 0.44±0.04†‡ |

| ET, ms | 65.88±2.67 | 47.16±2.19* | 58.04±3.80‡ |

| IVRT, ms | 22.74±3.06 | 39.21±3.02§ | 29.08±3.99†‡ |

HR indicates heart rate, PWTd, left ventricular posterior wall thickness diameter in diastole; PWTs, LV posterior wall thickness diameter in diastole in systole; EDD, end-diastolic LV dimension; ESD, end-systolic LV dimension; LVM/BM, LV mass/body mass; FS, endocardial fractional shortening; ET, ejection time; IVRT, isovolumic relaxation time; cMyBPC−/−+LcMyBPC, cMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− 21 days after gene transfer.

All values are expressed as mean±SE.

Significantly different from WT, P<0.001.

Significantly different from WT, P<0.05.

Significantly different from cMyBPC−/−, P<0.05.

Significantly different from WT, P<0.01.

Significantly different from cMyBPC−/−, P<0.01.

Figure 5.

Effects of cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBPC) gene transfer on in vivo cardiac function of cMyBPC−/− hearts. Two-dimensional echocardiography images acquired in M-mode along the parasternal short-axis view showing contractility of (A) wild-type (WT), (B) lentiviruses encoding the full-length cMyBPC (LcMyBPC)–treated cMyBPC−/−, and (C) untreated cMyBPC−/− hearts. cMyBPC expression in the LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− heart that is depicted was 96% of the cMyBPC expression in the WT heart. D, Total cMyBPC expression (normalized to α-actinin levels) as quantified by Western blotting of left ventricular homogenates of WT (lane 1), LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− (lane 2), and cMyBPC−/− (lane 3) hearts that were studied by in vivo echocardiography.*Significantly different than WT, P<0.05; †significantly different than untreated cMyBPC−/−, P<0.05. E, Confocal images of immunohistochemical staining of cMyBPC in midventricular slices isolated from LcMyBPC-treated (left) and untreated (right) cMyBPC−/− hearts. Left ventricular slices prepared from the apex (F), midventricle (G), and base (H) of a cMyBPC−/− heart treated with LcMyBPC (×60 magnification). ESD indicates end-systolic dimension, EDD, end-diastolic dimension.

The expression and localization of cMyBPC in the myocardium of LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts were further analyzed by immunohistochemistry in serial sections cut from the apex, mid-LV, and base. LcMyBPC-treated hearts that showed significant improvements in in vivo function exhibited robust cMyBPC expression (Figure 5) throughout the myocardium, even in regions of the LV distal from the injection site, whereas in LcMyBPC-treated hearts that did not show marked improvements in in vivo function, cMyBPC expression was mostly localized to regions proximal to the viral injection site and was usually absent in the distal base region (data not shown).

Discussion

The majority of treatment modalities for heart failure are mostly focused on delaying or preventing mechanisms that contribute to pathological cardiac remodeling to preserve or improve contractile function and myocyte viability.20,21 Commonly prescribed therapies for treatment of heart failure include afterload reduction, blockade of the β-adrenergic and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone cascades, cardiac fibrosis, and hypertrophy. However, because the primary cause that contributes to the pathophysiology of FHC mutations is most commonly perturbed myofilament function caused by mutations in sarcomeric proteins, therapies aimed at correcting myofilament dysfunction may be more effective than therapies aimed at downstream pathological compensatory mechanisms. Our results here suggest that viral gene transfer into the cMyBPC−/− myocardium increases the levels of cMyBPC in the sarcomere and concomitantly reverses myofilament contractile dysfunction and improves in vivo cardiac performance.

Effects of cMyBPC Gene Transfer on Myofilament Contractile Function

The main purpose of this investigation was to determine whether in vivo gene transfer of cMyBPC into the cMyBPC-deficient myocardium can reverse the acceleration of cross-bridge kinetics at the myofilament level. Our data demonstrate that LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− myocardium displays high expression of cMyBPC without changes in the expression or phosphorylation of other myofilament proteins (Figure 1). Some studies using skinned myocardium isolated from cMyBPC knockout mice have reported decreases8 or increases22,23 in Ca2+ sensitivity of force, but other studies11,13,14,16,24 have shown that the absence of cMyBPC does not affect isometric steady-state force generation. It is possible that differences in the reported effects of cMyBPC on force generation may be related to alterations in the expression of thin filament proteins in the different mouse models, such as troponin I isoforms23 that can also affect submaximal force generation and differences in study protocols, that is, types of myocardial preparations used and experimental temperature. Here, we found that cMyBPC ablation did not affect steady-state isometric force generation. Because force generation is proportional to the number of strongly bound cross-bridges and the time cross-bridges are in strongly bound states, accelerated cross-bridge attachment and detachment because of cMyBPC ablation14,24 promotes cross-bridge transitions to force-generating states but also reduces the time cross-bridges remain in strongly bound states, with the net effect being relatively preserved duty ratios and force generation. Consistent with this argument, increased expression of cMyBPC in cMyBPC−/− myocardium did not alter steady-state Ca2+-independent or Ca2+-dependent isometric force generation (Figure 3). In contrast, cross-bridge kinetics were dramatically slowed in LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− myocardium, both 21 days and 20 weeks after gene transfer (Figures 3 and 4), such that ktr and rates of force relaxation and development after acute stretch were similar to WT. Importantly, the salutary effects of viral-driven cMyBPC expression on contractile function in cMyBPC−/− myocardium were not transient but rather were maintained during a period of 20 weeks. Furthermore, using a complementary in vitro approach, we demonstrate that cMyBPC reconstitution of skinned myocardium isolated from cMyBPC−/− hearts with recombinant cMyBPC results in a similar slowing of cross-bridge kinetics24 as cMyBPC gene transfer in vivo (Figure 3), confirming that increased cMyBPC expression was responsible for changes in contractile function at the myofilament level in LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− myocardium.

The content of cMyBPC in myocardial preparations isolated from LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts and cMyBPC−/− fibers incubated with recombinant cMyBPC in vitro was similar to the cMyBPC content of WT fibers. However, none of the fibers analyzed after in vivo or in vitro cMyBPC reconstitution expressed cMyBPC at greater levels than WT fibers. These results indicate that there may be limited numbers of cMyBPC-binding sites that dictate the localization of cMyBPC within the thick filament and suggest that acute introduction of exogenous cMyBPC in the cMyBPC-deficient sarcomere results in a physiological cMyBPC stoichiometry. This observation is also in agreement with earlier studies,25–27 demonstrating that cMyBPC is arranged regularly along the thick filament and is only present in specific regions within the A-band.

The mechanism by which incorporation of exogenous cMyBPC into cMyBPC−/− myocardium results in normal cross-bridge behavior likely involves restored interactions of the cMyBPC N-terminal domains, with the S2 region of myosin near the myosin lever arm region that inhibits binding of myosin cross-bridges to actin, thereby slowing rates of cross-bridge attachment.14,24 In addition, cMyBPC may prolong the strongly bound state of cross-bridges to prevent their premature detachment from actin after completion of the cross-bridge powerstroke and augment the structural stability and longitudinal rigidity of the sarcomere16,17,28 via interactions of the C-terminal domain of cMyBPC with titin and the tail region of myosin.

Effects of cMyBPC Gene Transfer on In Vivo Contractile Function

Accelerated cross-bridge kinetics because of a lack of cMyBPC in the sarcomere lead to a truncated duration of systolic ejection and impair LV relaxation leading to diastolic dysfunction.9–12 Our in vitro studies demonstrated cMyBPC gene transfer reversed myofilament contractile dysfunction in skinned myocardium; therefore, it was of interest to study the effects of cMyBPC gene transfer on whole-organ cardiac contractile function in cMyBPC−/− mice. The cMyBPC gene transfer technique used here (ie, a single injection of LcMyBPC into the LV wall) was not specifically designed to transduce the whole cMyBPC−/− myocardium and resulted in variable cMyBPC expression. However, in some cMyBPC−/− hearts, high cMyBPC expression was achieved, even in regions distal to the injection site (Figure 5), which resulted in dramatically improved systolic and diastolic contractile function (Figure 5), as evidenced by increased ejection times and shortened isovolumic relaxation times (Table 3). Prolonged ejection times and accelerated diastolic filling in LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− hearts may be explained by the molecular effects of cMyBPC on cross-bridge function, which prolong the lifetime of the strongly bound cross-bridge state28 and inhibit cross-bridge rebinding to actin during the isovolumic relaxation phase of diastole,22 respectively.

Previous studies have shown that transgenic cMyBPC expression of ≈40% on a cMyBPC-null background reversed abnormal contractile function and hypertrophy in the mouse heart, suggesting that complete reconstitution of cMyBPC is not required to rescue the cMyBPC-null phenotype.29 Here also, despite the heterogeneity of the efficiency of myocardial transduction by in vivo cMyBPC gene transfer, we observed consistent improvements in contractile function in cMyBPC−/− hearts, which graded with myocardial cMyBPC expression. Reductions in LV wall thickness were observed in LcMyBPC-treated cMyBPC−/− mice and were corroborated by decreases in the abundance of mRNA of molecular markers of hypertrophy (online-only Data Supplement Figure). However, significant improvements in LV morphology were most notable in cMyBPC−/− hearts expressing high levels of cMyBPC, whereas weaker expression of cMyBPC localized to the viral injection region did not consistently result in improvements in LV morphology. It is possible that, unlike transgenic expression of cMyBPC that presumably results in a uniform distribution of cMyBPC in different regions of the heart, focal expression of cMyBPC by acute gene transfer in the cMyBPC−/− heart is insufficient to fully rescue myocardial dysfunction.

Implications for Treatment of cMyBPC-Related FHC

Recent studies have shown that gene transfer interventions designed to enhance sequestration of Ca2+ into the sarcoplasmic reticulum to accelerate cardiac relaxation by increased expression of parvalbumin or SERCA2a [sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a isoform]30,31 may be effective for correcting contractile dysfunction and pathological remodeling in heart failure. However, there are few studies that have tested this approach in vivo in an animal model of FHC. Although the precise mechanisms by which mutations in cMyBPC lead to contractile dysfunction and LV hypertrophy are still being debated, there is evidence that reduced amounts of cMyBPC in the myocardium may be a common feature that contributes to contractile dysfunction in cMyBPC-related FHC.6,7 Therefore, this proof-of-concept study demonstrates the feasibility and use of in vivo cMyBPC gene transfer to increase levels of cMyBPC in the sarcomere and improve contractile function in a mouse model of FHC. Importantly, our data show that increasing cMyBPC expression in cMyBPC-deficient hearts may have therapeutic application to delay the emergence of FHC or reverse the pathological course of the disease. The development of cMyBPC gene therapy may be especially useful in the treatment of patients with compound heterozygous or homozygous cMyBPC mutations, which may result in significant reductions in the content of cMyBPC in the sarcomere, and are associated with severe cardiac dysfunction and high incidences of death at a young age.32–34

Limitations

Although this study suggests that cMyBPC gene therapy was effective in improving contractile function in a mouse model of cMyBPC-related FHC, several limitations require further consideration. Lentivirus vectors were used here because they can stably transduce nondividing cardiac myocytes and integrate into the host genome, thereby providing long-term gene expression, and have a sufficient cloning capacity to accommodate the cMyBPC cDNA. However, some questions remain regarding lentivirus biosafety, with concerns of potential insertional mutagenesis events,35 which were not investigated here. Furthermore, consistent and efficient global myocardial transduction of cMyBPC in vivo in larger mammalian hearts will require multiple direct injections of the LV wall or the use of systemic delivery techniques.36,37 Thus, further experiments will be required to refine in vivo lentivirus delivery methods and other viral gene delivery platforms, such as adeno-associated virus, which have shown promise in human clinical trials,35–37 should also be considered for myocardial cMyBPC delivery. The efficiency of cMyBPC gene transfer should also be examined in mouse models that express varying levels of endogenous cMyBPC similar to some patients with cMyBPC insufficiency because native cMyBPC may compete with the exogenous cMyBPC for binding sites in the thick filament.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Mutations in cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBPC) are among the most common causes of inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, accounting for >40% of all known cases worldwide. Although the precise disease mechanisms of cMyBPC-related hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are not fully understood, decreased expression of cMyBPC in the heart because of cMyBPC haploinsufficiency has been implicated as a common consequence of mutations in cMyBPC. Because cMyBPC is a crucial regulator of cardiac muscle contraction, the primary molecular defect of decreased cMyBPC expression in the myocardium is abnormal cross-bridge function and force generation at the myofilament level. Indeed, cMyBPC-null (cMyBPC−/−) mice display accelerated cross-bridge kinetics accompanied by impaired in vivo contractile function and left ventricular hypertrophy. Thus, development of novel sarcomere-specific treatments to correct abnormalities in cardiac muscle contractile function because of mutations in cMyBPC is critical to delay or prevent hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In the present study, we demonstrate that skinned myocardium isolated from cMyBPC−/− hearts after in vivo cMyBPC gene transfer displays improved contractile properties compared with untreated cMyBPC−/− myocardium, which were indistinguishable from wild-type myocardium and correlated with increases in cMyBPC expression. In the intact cMyBPC−/− heart, in vivo cMyBPC gene transfer resulted in overall improvements in contractile function and left ventricular morphology compared with untreated cMyBPC−/− hearts, despite heterogeneous cMyBPC expression. Although modifications are required to improve methods of cMyBPC delivery to the heart, this proof-of-concept study demonstrates that cMyBPC gene therapy may be a viable approach for treatment of cardiomyopathies related to mutations in cMyBPC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yi-Hsin Cheng for assistance with immunohistochemistry assays.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grant from the American Heart Association 09SDG2050195 (Dr Stelzer).

Footnotes

The online-only Data Supplement is available at http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.968941/-/DC1.

Disclosures

Dr Stelzer holds a provisional patent for cardiac myosin binding protein C gene delivery for correction of contractile dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Watkins H, Ashrafian H, Redwood C. Inherited cardiomyopathies. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1643–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morita H, Nagai R, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Sarcomere gene mutations in hypertrophy and heart failure. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:297–303. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris SP, Lyons RG, Bezold KL. In the thick of it: HCM-causing mutations in myosin binding proteins of the thick filament. Circ Res. 2011;108:751–764. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT, Bild DE. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults. Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation. 1995;92:785–789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Identifying sarcomere gene mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a personal history. Circ Res. 2011;108:743–750. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dijk SJ, Dooijes D, dos Remedios C, Michels M, Lamers JM, Winegrad S, Schlossarek S, Carrier L, ten Cate FJ, Stienen GJ, van der Velden J. Cardiac myosin-binding protein C mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: haploinsufficiency, deranged phosphorylation, and cardiomyocyte dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;119:1473–1483. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marston S, Copeland O, Jacques A, Livesey K, Tsang V, McKenna WJ, Jalilzadeh S, Carballo S, Redwood C, Watkins H. Evidence from human myectomy samples that MYBPC3 mutations cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy through haploinsufficiency. Circ Res. 2009;105:219–222. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris SP, Bartley CR, Hacker TA, McDonald KS, Douglas PS, Greaser ML, Powers PA, Moss RL. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cardiac myosin binding protein-C knockout mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:594–601. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012222.70819.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer BM, Georgakopoulos D, Janssen PM, Wang Y, Alpert NR, Belardi DF, Harris SP, Moss RL, Burgon PG, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Maughan DW, Kass DA. Role of cardiac myosin binding protein C in sustaining left ventricular systolic stiffening. Circ Res. 2004;94:1249–1255. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126898.95550.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagayama T, Takimoto E, Sadayappan S, Mudd JO, Seidman JG, Robbins J, Kass DA. Control of in vivo left ventricular [correction] contraction/relaxation kinetics by myosin binding protein C: protein kinase A phosphorylation dependent and independent regulation. Circulation. 2007;116:2399–2408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tong CW, Stelzer JE, Greaser ML, Powers PA, Moss RL. Acceleration of crossbridge kinetics by protein kinase A phosphorylation of cardiac myosin binding protein C modulates cardiac function. Circ Res. 2008;103:974–982. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrier L, Knöll R, Vignier N, Keller DI, Bausero P, Prudhon B, Isnard R, Ambroisine ML, Fiszman M, Ross J, Jr, Schwartz K, Chien KR. Asymmetric septal hypertrophy in heterozygous cMyBP-C null mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desjardins CL, Chen Y, Coulton AT, Hoit BD, Yu X, Stelzer JE. Cardiac myosin binding protein C insufficiency leads to early onset of mechanical dysfunction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:127–136. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.965772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Walker JW, Moss RL. Differential roles of cardiac myosin-binding protein C and cardiac troponin I in the myofibrillar force responses to protein kinase A phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2007;101:503–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stelzer JE, Fitzsimons DP, Moss RL. Ablation of myosin-binding protein-C accelerates force development in mouse myocardium. Biophys J. 2006;90:4119–4127. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer BM, Noguchi T, Wang Y, Heim JR, Alpert NR, Burgon PG, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Maughan DW, LeWinter MM. Effect of cardiac myosin binding protein-C on mechanoenergetics in mouse myocardium. Circ Res. 2004;94:1615–1622. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000132744.08754.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyland LR, Palmer BM, Chen Z, Maughan DW, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Kreplak L, Vigoreaux JO. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C is essential for thick-filament stability and flexural rigidity. Biophys J. 2009;96:3273–3280. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Somji A, Yu X, Stelzer JE. Altered in vivo left ventricular torsion and principal strains in hypothyroid rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1577–H1587. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00406.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stelzer JE, Larsson L, Fitzsimons DP, Moss RL. Activation dependence of stretch activation in mouse skinned myocardium: implications for ventricular function. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:95–107. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill JA, Olson EN. Cardiac plasticity. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1370–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frey N, Katus HA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Hypertrophy of the heart: a new therapeutic target? Circulation. 2004;109:1580–1589. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120390.68287.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pohlmann L, Kröger I, Vignier N, Schlossarek S, Krämer E, Coirault C, Sultan KR, El-Armouche A, Winegrad S, Eschenhagen T, Carrier L. Cardiac myosin-binding protein C is required for complete relaxation in intact myocytes. Circ Res. 2007;101:928–938. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cazorla O, Szilagyi S, Vignier N, Salazar G, Krämer E, Vassort G, Carrier L, Lacampagne A. Length and protein kinase A modulations of myocytes in cardiac myosin binding protein C-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen PP, Patel JR, Rybakova IN, Walker JW, Moss RL. Protein kinase A-induced myofilament desensitization to Ca(2+) as a result of phosphorylation of cardiac myosin-binding protein C. J Gen Physiol. 2010;136:615–627. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craig R, Offer G. The location of C-protein in rabbit skeletal muscle. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1976;192:451–461. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1976.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett P, Craig R, Starr R, Offer G. The ultrastructural location of C-protein, X-protein and H-protein in rabbit muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1986;7:550–567. doi: 10.1007/BF01753571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pepe FA, Drucker B. The myosin filament. III. C-protein. J Mol Biol. 1975;99:609–617. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer BM, Sadayappan S, Wang Y, Weith AE, Previs MJ, Bekyarova T, Irving TC, Robbins J, Maughan DW. Roles for cardiac MyBP-C in maintaining myofilament lattice rigidity and prolonging myosin crossbridge lifetime. Biophys J. 2011;101:1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadayappan S, Gulick J, Osinska H, Martin LA, Hahn HS, Dorn GW, 2nd, Klevitsky R, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Robbins J. Cardiac myosin-binding protein-C phosphorylation and cardiac function. Circ Res. 2005;97:1156–1163. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190605.79013.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jessup M, Greenberg B, Mancini D, Cappola T, Pauly DF, Jaski B, Yaroshinsky A, Zsebo KM, Dittrich H, Hajjar RJ Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID) Investigators. Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID): a phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2011;124:304–313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.022889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szatkowski ML, Westfall MV, Gomez CA, Wahr PA, Michele DE, DelloRusso C, Turner II, Hong KE, Albayya FP, Metzger JM. In vivo acceleration of heart relaxation performance by parvalbumin gene delivery. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:191–198. doi: 10.1172/JCI9862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zahka K, Kalidas K, Simpson MA, Cross H, Keller BB, Galambos C, Gurtz K, Patton MA, Crosby AH. Homozygous mutation of MYBPC3 associated with severe infantile hypertrophic cardiomyopathy at high frequency among the Amish. Heart. 2008;94:1326–1330. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.127241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lekanne Deprez RH, Muurling-Vlietman JJ, Hruda J, Baars MJ, Wijnaendts LC, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Alders M, van Hagen JM. Two cases of severe neonatal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by compound heterozygous mutations in the MYBPC3 gene. J Med Genet. 2006;43:829–832. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.040329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortiz MF, Rodríguez-García MI, Hermida-Prieto M, Fernández X, Veira E, Barriales-Villa R, Castro-Beiras A, Monserrat L. A homozygous MYBPC3 gene mutation associated with a severe phenotype and a high risk of sudden death in a family with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62:572–575. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)71841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapti K, Chaanine AH, Hajjar RJ. Targeted gene therapy for the treatment of heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:265–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis J, Westfall MV, Townsend D, Blankinship M, Herron TJ, Guerrero-Serna G, Wang W, Devaney E, Metzger JM. Designing heart performance by gene transfer. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1567–1651. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ly H, Kawase Y, Yoneyama R, Hajjar RJ. Gene therapy in the treatment of heart failure. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:81–96. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00037.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.