Abstract

Intestinal homeostasis is maintained by intestinal stem cells (ISCs) and their progenies. A complex autonomic nervous system spreads over posterior intestine. However, whether and how neurons regulate posterior intestinal homeostasis is largely unknown. Here we report that neurons regulate Drosophila posterior intestinal homeostasis. Specifically, downregulation of neuronal Hedgehog (Hh) signaling inhibits the differentiation of ISCs toward enterocytes (ECs), whereas upregulated neuronal Hh signaling promotes such process. We demonstrate that, among multiple sources of Hh ligand, those secreted by ECs induces similar phenotypes as does neuronal Hh. In addition, intestinal JAK/STAT signaling responds to activated neuronal Hh signaling, suggesting that JAK/STAT signaling acts downstream of neuronal Hh signaling in intestine. Collectively, our results indicate that neuronal Hh signaling is essential for the determination of ISC fate.

Keywords: Hh signaling, intestinal stem cell, neuron, Drosophila

Introduction

Recently, intestinal stem cells (ISCs) have been identified in Drosophila. The mechanism of ISC-related intestinal regeneration is remarkably similar to that of mammalian epithelia [1–4]. Drosophila ISCs, located adjacent to the basement membrane of the midgut epithelium, can undergo asymmetric self-renewing divisions in most situations and produce non-dividing, undifferentiated cells termed enteroblasts (EBs) [5–7]. EB can further terminally differentiate into either an absorptive enterocyte (EC) or a secretory enteroendocrine cell (EE) [3, 4] (Figure 1a).

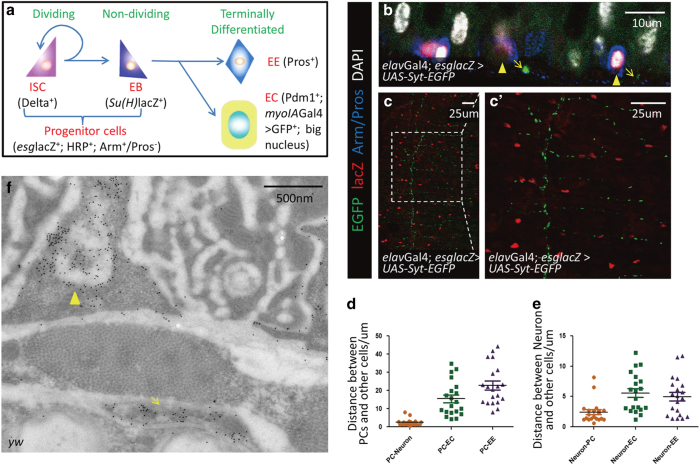

Figure 1.

Progenitor cells are located in the vicinity of neurons in Drosophila posterior intestine. (a) A diagram of Drosophila midgut stem cell self-renew, differentiation and the cell type-specific markers used in this study. (b–c′) Immunostaining of the longitudinal section of midgut (b) and the overview of midgut (c and c′). Neurons (arrows; UAS-Syt-EGFP+: green) and intestinal progenitor cells (arrowheads; Arm+/Pros−: blue staining in cytoplasm; esglacZ+: red) are located in the vicinity of each other. elavGal4 is specifically expressed in neurons. (d) Distance between intestinal progenitor cells (PCs) and other cells. Distances between the majority of PCs and synapses are <5 μm, while PCs, ECs and EEs distribute randomly. (e) The distances between synapses and other cells. ECs and EEs do not show distribution relevance with neurons. (f) Immuno-TEM of HRP-labeled neurons (arrow) and intestinal progenitor cells (arrowhead). These two types of cells tend to appear together. See also Supplementary Figure S1.

Dysfunctions of intestinal epithelial barrier observed in various diseases are associated with enteric nervous system neuropathies [8]. Enteric nervous system is involved in several critical functions of intestinal epithelial barrier such as permeability, motility and mucosal secretion. However, it remains unknown whether neurons directly affect intestinal epithelial cells [8, 9]. Owing to the intricate nature of nervous system in mammals, it is challenging to study the role of neurons on intestinal epithelial cells. In this regard, invertebrate models, such as Drosophila, are simple and genetically amenable alternatives. Indeed, the past decade has witnessed increasing mechanistic studies of neurodegenerative diseases in flies [10].

In this study, we revealed an important role of neuronal Hedgehog (Hh) signaling in the maintenance of posterior intestinal homeostasis in Drosophila. Neuron ablation causes an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells, a reduction of ECs and an increased proliferation rate of ISCs. Neuronal Hh signaling is essential for neuron’s regulatory effects on posterior intestine, as loss of Hh ligand in epithelial cells induces similar phenotypes as that caused by downregulation of neuronal Hh signaling. Moreover, JAK/STAT signaling in intestinal progenitor cells could respond to activated neuronal Hh signaling, indicating a genetic interaction between neuronal Hh signaling and JAK/STAT signaling in the regulation of intestinal homeostasis. Together, these results highlight the importance of interorgan communication during intestinal homeostasis, which may facilitate further exploration of the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Results

Progenitor cells locate in the vicinity of neurons in Drosophila posterior intestine

Inspired by previous observation of innervation in Drosophila adult intestine [11, 12], we set out to investigate whether neurons were involved in the regulation of Drosophila intestinal homeostasis. To this end, we first examined the localization of neurons in midgut using elavGal4; UAS-syt-EGFP flies, in which GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) expression is restricted to neurons. Consistent with previous studies [3, 4, 13], we found that intestinal progenitor cells were located in the basal layer of intestines (Supplementary Figures S1A–A′′ and B–B′′), where GFP-marked neurons were absent. Meanwhile, GFP-marked neurons were found attached to the visceral muscle sheath adjacent to the intestinal epithelia (Supplementary Figures S1A and A′′′, and B–B′′′). Confocal imaging showed that most intestinal progenitor cells were located in the vicinity of neurons (Figures 1b and c, c′). We then measured distances between synapses and their nearby intestinal progenitor cells. Our statistic results indicate that the majority of intestinal progenitor cells were located in a region within 5 μm away from neurons (Figures 1d and e), while other types of cells distribute randomly. To confirm these observations, we next performed immuno-transmission electron microscopy (immuno-TEM) by using HRP (Horseradish Peroxidase), a marker for both neuron and intestinal progenitor cells [6, 14], to localize neurons and progenitor cells in the intestine. As shown in Figure 1f, these two types of cells can be distinguished according to their locations: intestinal progenitor cells are located in the basal layer, whereas neurons are attached to the visceral muscle sheath adjacent to the intestinal epithelia. Similarly, one can also distinguish intestinal progenitor cells from EEs based on their distinct locations. Taken together, these results indicate that intestinal progenitor cells are indeed located in the vicinity of neurons (Figure 1f).

Neurons are required for the regulation of posterior intestinal homeostasis

To directly test whether neurons contribute to the regulation of Drosophila intestinal homeostasis, we ablated neurons by overexpressing the cell death gene grim (an inhibitor of Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis-1) along with a temperature-sensitive Gal4 repressor, tubGal80ts [15] (referred to as grimts in figures). After UAS-grim expression was induced for 1 week, GFP signal could no longer be detected when compared with control, indicating an ablation of neurons (Supplementary Figures S2A and B). Intriguingly, we observed an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells in the midgut under this condition (Figures 2a and b). Intestinal progenitor cells include ISCs and EBs. To further distinguish the specific cell type of the accumulated intestinal progenitor cells, we stained the markers of ISCs and EBs. The results showed that both ISC-like cells and EB-like cells were accumulated (Figures 2c–f), suggesting that the differentiation of ISCs to EBs were not blocked. These results were further confirmed by TEM analysis (Figures 2g–i) and quantitative PCR analysis of delta (ISCs-specific) and esg (intestinal progenitor cells-specific) expression (Figure 2j and Supplementary Figure S2C). Together with our immunostaining, these observations suggest that neuron ablation leads to an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells.

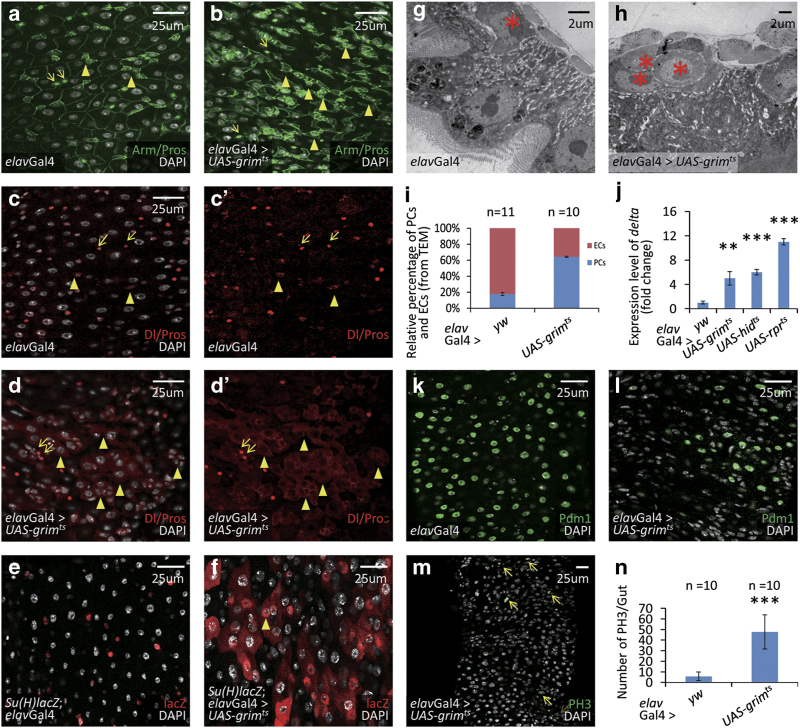

Figure 2.

Neurons have an important role in the regulation of homeostasis in Drosophila posterior midgut. (a and b) Immunostaining of intestinal progenitor cells (arrowheads; Arm+/Pros−: green staining in cytoplasm) and EEs (arrows; Arm+/Pros+: green staining in cytoplasm, along with strong green staining in nucleus) in control (a) and neuron-ablated (b) flies. Neurons were ablated by overexpressing cell death gene grim. After neuron ablation, there is an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells. (c–d′) Immunostaining of ISCs (arrowheads; Delta+: red staining in cytoplasm) and EEs (arrows; Pros+: red staining in nucleus) in control (c, c′) and neuron-ablated (d, d′) flies. After neuron ablation, there is an accumulation of ISCs. (e, f) Immunostaining of EBs (Gbe-Su(H)-lacZ+: red) in intestines of control (e) and neuron-ablated (f) flies. After neuron ablation, there is an accumulation of EBs and many of them show large nuclei, resembling ECs (arrowheads; f). (g, h) TEM images of Drosophila guts in control (g) and neuron-ablated (h) flies. Intestinal progenitor cells are located next to base membrane and are marked with asterisk. After neuron ablation, there is an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells. (i) Statistic results of the relative percentage of intestinal progenitor cells (PCs) and ECs from TEM. The depicted result is the average data from two independent experiments. (j) Quantitative PCR analysis of the ISC-specific marker delta. After grim, hid or rpr-mediated neuron ablation, the expression level of delta in total intestine is significantly increased (**P<0.01, ***P<0.005). Shown are means±s.d. from three independent experiments. In every experiment, at least 10 intestines were pooled together for analysis. (k, l) Immunostaining of ECs (Pdm1+: green) in control intestine (k) and neuron-ablated flies (l). Neuron ablation causes a reduction of ECs (l). (m) Immunostaining of ISCs with mitotic activity (arrows; PH3+: green). The proliferation rate is markedly increased after neuron ablation. (n) Quantitative analysis of dividing ISC cells (PH3+) in the intestines of control and neuron-ablated flies. Shown are the mean±s.d., ***P<0.005. See also Supplementary Figures S2 and 3.

During its differentiation into EC, the EB cell becomes bigger with an enlarged, polyploid nucleus. We observed that after neuron ablation, there were many EB marker-positive cells that also had large nuclei (Figures 2e and f), suggesting a defect of EB differentiation toward EC. To test this possibility, we analyzed the formation of terminally differentiated ECs and EEs. In the absence of neurons, the number of ECs (Pdm1 positive) markedly decreased (Figures 2k and l), whereas the number of EEs remained largely unchanged (Figures 2c–d′), implying that neuron ablation blocks the differentiation of intestinal progenitor cells toward ECs. We also examined the proliferation of ISCs and found that the number of mitotic phospho-Ser10-histone3 (PH3)-positive ISCs increased by several folds (Figures 2m and n). Moreover, neuron ablation by two other cell death genes, rpr and hid, led to similar phenotypes as observed for grim overexpression (Figure 2j, and Supplementary Figures S2C–J), further confirming that neurons are essential for posterior intestinal homeostasis.

As our elavGal4 is expressed in intestinal progenitor cells (Supplementary Figures S3A–A′′′), one may concern that the above observations could be results from ablation of intestinal progenitor cells rather than neurons. To rule out this possibility, we tested the overexpression of grim, hid and rpr (inhibitors of Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis-1 [16]) specifically expressed in intestinal progenitor cells using esgGal4ts. Consistent with previous report [17], no obvious apoptosis were found for these intestinal progenitor cells (data not shown), indicating that the aforementioned phenotypes can be ascribed to the ablation of neurons. To further confirm this notion, we used pdfGal4 and ok371Gal4 drivers, which are reported to be expressed in neurons spreading over intestine. Similarly, we observed an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells and an increased proliferation rate of ISCs (Supplementary Figures S3B–H).

Abnormal Hh signaling in neurons induces similar phenotypes in posterior intestine as does neuron ablation

Hh signaling is a highly conserved pathway that governs the patterning of many organs during development. It can also act as a somatic stem cell factor in adults [18–21]. Previous studies have indicated that Hh signaling is involved in the homeostasis of the gastrointestinal tract in mammals [22–27]. However, it has not been clarified whether neurons are involved in this process. To address this question, we first investigated the potential role of Hh signaling in Drosophila intestinal homeostasis. To this end, we performed global downregulation and upregulation of Hh signaling using ptcGal4ts (ptcGal4 along with tubGal80ts). Strikingly, downregulation of Hh signaling resulted in similar phenotypes as did neuron ablation; while upregulation of Hh signaling resulted in largely opposite phenotypes (Supplementary Figures S4A–N). As Ci is the transcription factor of Hh pathway, loss of Ci will block Hh signaling pathway activity [20]. We then downregulated Hh signaling in neurons by expressing ci RNAits (along with tubGal80ts) using elavGal4 to investigate the potential role of neuronal Hh signaling on intestinal homeostasis. After 2 weeks of ci RNA interference (RNAi) overexpression, the morphology of neurons was normal (Supplementary Figures S5A–B′), whereas an obvious accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells was observed at 10 days (Figures 3a, b, d, e and p). Further staining for ISCs and EBs showed that both types of progenitor cells were accumulated, again suggesting that the differentiation of ISCs to EBs was not influenced by neuronal Hh signaling (Figures 3g–h’, j and k). These results were further confirmed by TEM and quantitative PCR (detecting esg and delta) experiments (Figures 3m, n and q, and Supplementary Figures S5D and E). In confocal images, we noticed that there were some abnormal EB-like cells with large nuclei, suggesting a defect of EBs differentiation to ECs. So we next investigated the terminally differentiated cells, ECs and EEs, and noticed a decrease of EC number and an increase of EE number (Figures 3d, e, g–h′, p, r and s). This observation suggests that downregulation of neuronal Hh signaling might delay the differentiation to ECs but not EEs. As an important component of Hh signaling, loss of Smoothened (Smo) downregulates Hh signaling pathway activity [20]. To confirm our hypothesis, we used smo RNAi to downregulate neuronal Hh pathway activity. All phenotypes above were reproduced in neuronal smo RNAits flies (smo RNAi along with tubGal80ts; Supplementary Figures S5D, F–G′, I, J, L, M and O–Q′). To rule out the possibility that EC number was reduced by increased apoptosis, we performed TUNEL assay. The results showed that no different apoptosis rate was induced by downregulated neuronal Hh signaling (Supplementary Figures S5S–V), further suggesting that the decreased EC number was caused by defective differentiation.

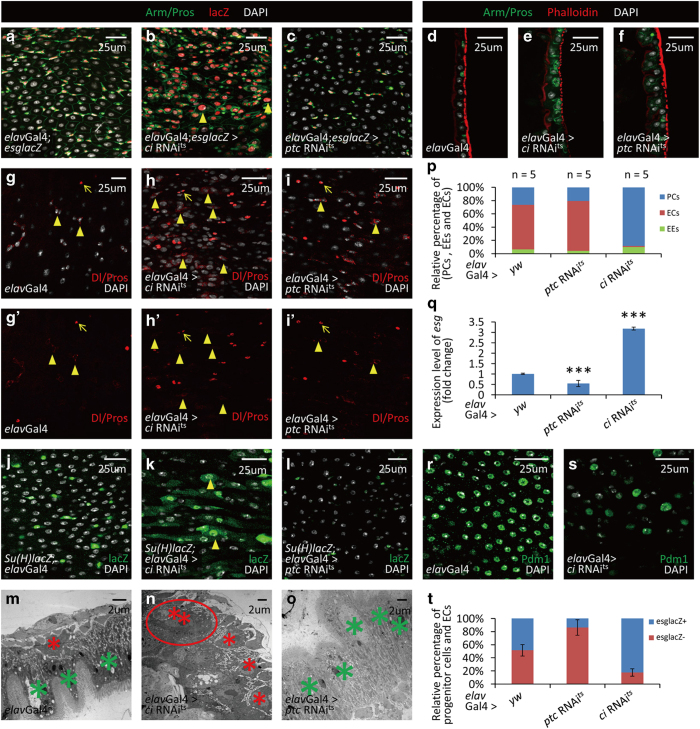

Figure 3.

Neuronal Hh signaling is essential for the posterior intestinal homeostasis in Drosophila. (a–c) Cross-section and (d–f) longitudinal section immunostaining of intestinal progenitor cells (Arm+/Pros−: green staining in cytoplasm without green staining in nucleus; esglacZ+: red), EEs (Arm+/Pros+: green staining in cytoplasm, along with strong green staining in nucleus) and ECs (big nuclei). Intestines were taken from control flies (a, d), neuron-specific ci RNAi flies (b and e) and neuron-specific ptc RNAi flies (c and f). Neuron-specific Hh suppression (ci RNAi, b, e) causes an accumulation of intestine progenitor cells and a reduction of ECs. There are some intestinal progenitor cells with large nuclei (arrowheads in b). Neuron-specific Hh activation (ptc RNAi, c, f) causes a reduction of intestinal progenitor cells and an increase of ECs. (g–i′) Immunostaining of ISCs (arrowheads; Delta+: red staining in cytoplasm) and EEs (arrows; Pros+: red staining in nucleus) in control (g, g′), neuron-specific ci RNAi (h, h′) and neuron-specific ptc RNAi (i, i′) flies. Overexpression of ci RNAi in neurons induces an increase of ISCs, while overexpression of ptc RNAi in neurons does not influence the number of ISCs. (j–l) Immunostaining of EBs (Gbe-Su(H)-lacZ+: red) in intestines of control (j), neuron-specific ci RNAi (k) and neuron-specific ptc RNAi (l) flies. Overexpression of ci RNAi in neurons induces an accumulation of EBs and some of them showed large nuclei (arrowheads, k). Overexpression of ptc RNAi in neurons causes a noticeable reduction of EBs (l). (m–o) TEM images of intestines from control (m), neuron-specific ci RNAi (n) and neuron-specific ptc RNAi (o) flies. Intestinal progenitor cells are small cells located near the base membrane (marked with red asterisk). ECs are big cells with villi (marked with green asterisk). Neuron-specific Hh suppression causes an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells and some of them form a cluster as same as that induced by neuron ablation (red circle). Neuron-specific Hh activation causes an increase of ECs. (p) Quantitative analysis of relative percentage of EEs, ECs and intestinal progenitor cells (PCs) per microscopic field (enlargement factor 10×40) in control, neuron-specific ci RNAi and neuron-specific ptc RNAi flies. (q) Quantitative PCR analysis of intestine progenitor-specific marker esg under indicated experimental conditions. The depicted data are mean±s.d. from three independent experiments. In every experiment, at least 10 intestines were pooled together, ***P<0.005. (r and s) Shown in (r) are immunostaining of ECs from intestines of control flies. ECs (Pdm1+: green) are reduced after neuron-specific Hh suppression (s). (t) Statistic results of BrdU tracing experiments in fly intestine. After ptc RNAi expression in neurons, the most of BrdU-labeled cells are ECs (esglacZ−; big nuclei. See Supplementary Figures S5B–B′′). After ci RNAi expression in neurons, the most of BrdU-labeled cells are intestinal progenitor cells (esglaZ+. See Supplementary Figures S5C–C′′). The results showed here are data averaged from two independent experiments. In every experiment, at least 20 intestines were covered. See also Supplementary Figures S4–7.

Taken together, these results indicate that neuron ablation and downregulation of neuronal Hh activity have similar effects on midgut homeostasis, such as increased intestinal progenitor cells and decreased ECs.

We then asked how upregulation of neuronal Hh activity might influence intestinal homeostasis. As Patched (Ptc) is a negative regulator of Hh signaling [20], we used flies that specifically express ptc RNAits (ptc RNAi along with tubGal80ts) in neurons to upregulate Hh signaling activity. The phenotypes were largely opposite to those observed in flies with neuronal Hh downregulation. After Hh signaling activation in neurons, a noticeable reduction of intestinal progenitor cells was observed (Figures 3a, c, d, f and p), while the morphology of neurons was not influenced (Supplementary Figures S5A, A′ and C, C′). Quantitative PCR analysis showed a ~40% reduction of esg, an intestinal progenitor cell-specific gene (Figure 3q). Staining of ISCs and EBs showed that even though there was no reduction of ISCs, the number of EBs was significantly reduced (Figures 3g and g′, i, i′ j and l). This observation was further confirmed by UAS-ci103 (a consistent activated form of Ci) overexpression experiments (Supplementary Figures S5F, F′, H, H′, K and N). As the reduced number of EBs might be owing to their increased differentiation toward ECs, we then analyzed the number of ECs. The result suggests that the density of ECs was higher after neuronal Hh signaling activation. The majority of these extra cells contained large nuclei with Armadillo (Arm) staining restricted to cell membrane and positive Pdm1 staining, indicating that they were ECs (Figures 3d, f and p, and Supplementary Figures S5R–R′). The results from TEM also showed that, compared with the control, ECs were more crowded when ptc RNAi was induced (Figures 3m and o, and Supplementary Figure S5E). Taken together, these data indicate that activation of neuronal Hh signaling significantly influences posterior intestinal homeostasis by reducing intestinal progenitor cells and accumulating ECs (Figure 3p).

Neuronal Hh signaling has an important role in the differentiation of progenitor cells towards ECs

Based on the above results, we hypothesized that neuronal Hh signaling might have an important role in regulating the differentiation of intestinal progenitor cells into ECs. To test this possibility, we traced cell fate with BrdU and found that the majority of BrdU-labeled cells were ECs when neuronal Hh signaling was activated, whereas the majority of BrdU-labeled cells was intestinal progenitor cells when neuronal Hh signaling was downregulated (Figure 3t, and Supplementary Figures S6A–C′′). Together, these results suggest that activation of neuronal Hh signaling can promote the differentiation of ISCs toward ECs.

As elavGal4 could also be expressed in intestinal progenitor cells, one may concern that the observations might be induced by RNAis in intestinal progenitor cells. To rule out this possibility, we performed staining using antibodies against Ci/Smo/Ptc protein in intestine. The results showed no detectable signals of these proteins in intestinal progenitor cells (Supplementary Figures S7A–B′′′), suggesting that none of these proteins located in intestinal progenitor cells. Next, we downregulated ci/smo/ptc specifically in intestinal progenitor cells using esgGal4ts. After inducing the expression of ci/smo/ptc RNAi and UAS-ci103 for 10 days, neither immunostaining nor realtime (RT)-PCR results showed marked changes (Supplementary Figures S7C–H).

Interestingly, while studying the function of activated neuronal Hh signaling, we noticed that the phenotypes caused by the overexpression of UAS-smo and UAS-smoSD123 (a super-activated mutation of Smo) were largely opposite. Overexpression of UAS-smo in neurons induced an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells and an increased proliferation rate of ISCs. On the contrary, overexpression of UAS-smoSD123 induced a reduction of intestinal progenitor cells and a decreased proliferation rate (Supplementary Figures S7I–L). These results suggest that neuronal Hh signaling acts in a dose-dependent manner.

Hh ligand deficiency in ECs induces similar phenotypes as does loss of neuronal Hh signaling

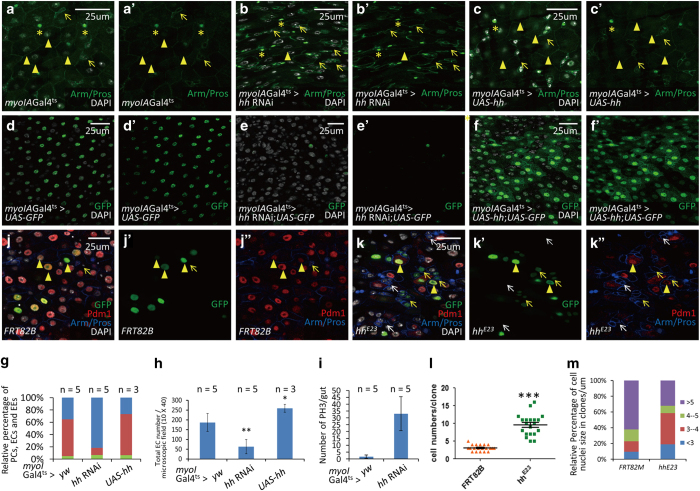

Recently, it is reported that Hh protein might originate from multiple sources, including intestinal progenitor cells and ECs in epithelia [28]. We used esgGal4ts and myoIAGal4ts, respectively, to demonstrate the function of Hh ligand in intestinal progenitor cells and ECs. However, when hh expression was downregulated in intestinal progenitor cells with esgGal4ts, the majority of guts (14 out of 20) showed no detectable changes (data not shown). These results suggest that Hh ligand secreted by intestinal progenitor cells has a limited role, if any, in the determination of ISCs’ fate. On the other hand, when hh RNAi was expressed in ECs (via myoIAGal4ts, along with tubGal80ts), the intestinal progenitor cells were accumulated (Figures 4a–b′, and Supplementary Figures S8A–B′), whereas the number of ECs was reduced (Figures 4d–e′, g and h, and Supplementary Figures S8A–B′). All these phenotypes resembled that caused by neuron ablation and downregulation of neuronal Hh signaling (Figures 2a, b, k and l). In addition, an increased proliferation rate of ISCs was observed when hh was downregulated in ECs (Figure 4i and Supplementary Figure S8D). Moreover, although overexpression of UAS-hh in ECs caused no marked changes of intestinal progenitor cells (Figures 4c, c′ and g, and Supplementary Figures S8C and C′), ECs were accumulated (Figures 4f, f′, g and h, and Supplementary Figures S8C–C′), which was similar as activated neuronal Hh signaling. These results suggest that neuronal Hh signaling responds to Hh ligand secreted by ECs instead of secreted by intestinal progenitor cells. To further confirm our findings, we used the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) system by using a hh deficiency line, hhE23. After clones were induced for 72 h, hhE23 clones were bigger compared with the control FRT82B clones (Figures 4j–k′′ and l), indicating an increased proliferation rate of ISCs. When there was a high density of Hh mutant clones, the majority of cells in and around these clones were small nuclei cells with Arm staining positive and Pdm1 negative (Figures 4j–m), indicating that they were intestinal progenitor cells. Loss of Hh ligand in ECs impaired the differentiation of adjacent ISCs into ECs. These results suggest that neuronal Hh signaling responds to Hh ligand secreted by ECs, thereby influences the cell fate of the neighboring ISCs. These results were further confirmed in hhGal4ts flies (Supplementary Figures S8E–K). Taken together, these results indicate that Hh secreted by ECs significantly impacts intestinal homeostasis.

Figure 4.

Loss of Hh ligand in epithelial cells induces similar phenotypes as that induced by loss of neuronal Hh signaling. (a–c′) Immunostaining of intestinal progenitor cells, ECs and EEs in control (a, a′), EC-specific hh RNAi (b, b′) and EC-specific UAS-hh overexpressing (c, c’) flies. MyoIAGal4ts is an EC-specific driver. Intestinal progenitor cells are Arm+/Pros− (arrows; green staining in cytoplasm without green staining in nucleus); EEs are Arm+/Pros+ (asterisk; green staining in cytoplasm, along with strong green staining in nucleus); Cells with big nuclei (arrowheads; white nucleus) are ECs cells in control (a, a′). After hh knockdown, these cells become EC-like cells but lack of EC markers myoIAGal4-GFP (e, e′). hh RNAi expression causes a relative increase of intestinal progenitor cells, while the number of EEs remains largely the same. Overexpression of UAS-hh does not induce marked changes of intestinal progenitor cells or EEs. (d–f′) Cross-section immunostaining of ECs (myoIAGal4ts>GFP+: green) in intestine of control (d, d′), EC-specific hh RNAi (e, e′) and EC-specific UAS-hh overexpressing (f, f′) flies. After hh knockdown, there is a reduction of ECs, while overexpression of hh causes an accumulation of ECs. (g) Quantitative analysis of the relative percentage of EEs, ECs and intestinal progenitor cells per microscopic field (enlargement factor 10×40) in the intestines of control, hh RNAi and UAS-hh flies. (h) Quantitative analysis of the EC number per microscopic field (enlargement factor 10×40) in the intestine of control and hh RNAi flies. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (i) Quantitative analysis of dividing ISC cells (PH3+) in the intestines of control and hh RNAi flies. The results depicted here are means±s.d., ***P<0.005. (j, k′′) Adult midguts containing GFP-labeled FRT82B clones (j, j′′) and hhE23 clones (k, k′′) were immunostained to show the expression of GFP (green in j, j′ and k, k′′), Arm/Pros (cytoplasmic blue in j, j′′ and k, k′′), Pdm1 (red in j, j′′ and k, k′′). In FRT82B clones, GFP-positive cells have big nuclei and are Pdm1 staining positive (arrowheads), indicating that they are ECs. Intestinal progenitor cells inside clones are marked with yellow arrow and intestinal progenitor cells outside clones are marked with white arrow (j, j′′). In hhE23 guts, the majority of neighboring cells (in and outside clones) of GFP-positive ECs are small nuclei cells with Pdm1 staining negative and Arm staining positive (inside clones: yellow arrows; outside clones: white arrows), indicating that they are intestinal progenitor cells. The minority of GFP-positive cells are big nuclei cells with Pdm1 staining positive (arrowheads), indicating that they are ECs (k, k′′). Guts were dissected out from adult flies grown at 29 °C for 5 days after clone induction. (l) Statistics data of the cell number in FRT82B clones and hhE23 clones. hhE23 clones are bigger than FRT82B clones, indicating an increased proliferation rate. Five guts were analyzed. The data depicted are means±s.d., ***P<0.005. (m) Relative percentage of cell nuclei size in FRT82B and hhE23 clones. The majority of cells in hhE23 clones are small nuclei cells. Five guts were analyzed. See also Supplementary Figures S8 and 9.

To further explore the relationship between EC-secreted Hh ligand and neuronal Hh signaling, we combined neuronal ci RNAi and hh overexpression in ECs flies together. As a result, these flies showed an accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells compared with control (ci RNAi in ECs flies) highly similar as does neuronal ci RNAi (Supplementary Figures S9A–D′), suggesting that neuronal ci RNAi exert a role in intestinal homeostasis downstream of EC-secreted Hh ligand.

JAK/STAT signaling acts downstream of neuronal Hh signaling

Subsequently, on one hand, we found that JAK/STAT signaling was not significantly changed after neuronal ci RNAi was induced. On the other hand, both immunostaining and RT-PCR results showed that JAK/STAT signaling in intestine was upregulated in intestinal progenitor cells after neuronal ptc RNAi was induced (Figures 5a–d, and Supplementary Figures S10A–C′), indicating that JAK/STAT signaling could respond to activated neuronal Hh signaling and acts downstream of neuronal Hh signaling in intestine homeostasis.

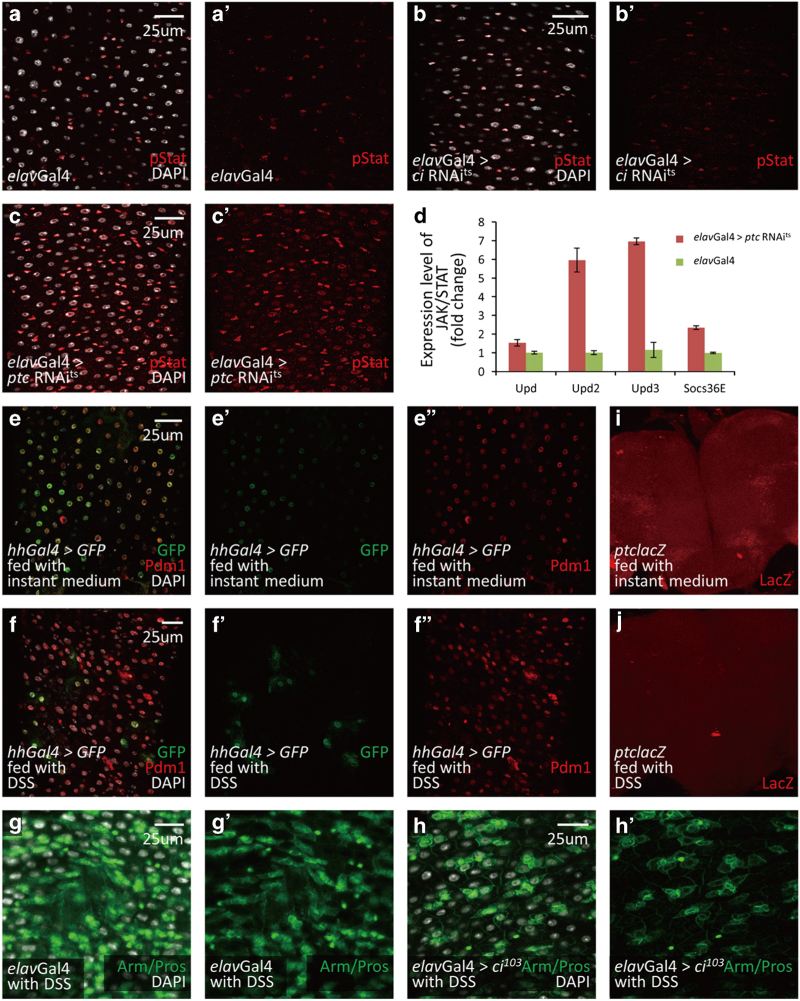

Figure 5.

The role of neuronal Hh signaling on intestine is dependent on JAK/STAT signaling. (a–c′) Immunostaining of pSTAT in control (red, a, a′), neuronal ci RNAi (red, b, b′) and neuronal ptc RNAi (red, c, c′) flies. JAK/STAT signaling does not change when neuronal Hh signaling is downregulated (b, b′). However, JAK/STAT signaling is upregulated when neuronal Hh signaling is upregulated (c, c′). (d) Quantitative PCR analysis of JAK/STAT signaling ligands and target gene Socs36E under indicated experimental conditions. The depicted data are means±s.d. from three independent experiments. In every experiment, at least 10 intestines were pooled together. (e, f′′) Immunostaining of hhGal4>UAS-GFP (green) and ECs (Pdm1+: red) in control gut (e–e′′) and DSS-induced gut (f–f′′). DSS treatment induced a reduction of Hh-secreted cells. (g–h′) Immunostaining of intestinal progenitor cells (Small nuclei; Arm+/Pros−: green) in DSS-induced control gut (g, g′) and neuronal Hh activation gut (h, h′). Neuronal Hh activation partially rescues the phenotype caused by DSS treatment. (i, j) Immunostaining of ptc-lacZ (red) in control brain (i) and DSS-induced brain (j). DSS treatment induces downregulation of Hh signaling level in brain. See also Supplementary Figures S10–12.

Neuronal Hh signaling regulates DSS-induced midgut regeneration

In addition to its role in intestinal homeostasis under normal physiological context, neuronal Hh signaling is also required for maintaining damage-induced midgut homeostasis. It has been reported that dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) interferes with intestinal homeostasis via the disruption of basement membrane organization [29]. We found that, when treated with DSS, the number of cells expressing hh was decreased (Figures 5e–f′′). However, DSS-induced increase of intestinal progenitor cells was partially reversed by neuronal Hh signaling activation (Figures 5g–h′, and Supplementary Figures S11A–B′′), suggesting that Hh signaling is also involved in the regulation of damage-induced intestinal homeostasis.

Discussion

In this study, we uncovered an essential role of neurons and neuronal Hh signaling in adult Drosophila ISC fate determination. Our data indicate that neuronal Hh signaling promotes the differentiation of ISCs toward ECs, highlighting a critical role of neurons in ISC niche and intestinal homeostasis. Our findings not only demonstrate the complexity of interorgan communications but also provide important clues for further understanding the comprehensive function of Hh signaling in posterior intestinal homeostasis.

In the past few years, mammalian enteric nervous system was found to be involved in multiple regulatory processes of gut functions, including motility, mucosal secretion and host defense. However, the role of enteric nervous system in intestinal epithelial cell homeostasis remains elusive [8, 9]. Here, we showed that neuron ablation resulted in aberrant posterior intestinal homeostasis, featured by accumulation of intestinal progenitor cells, reduction of ECs and increased proliferation rate of ISCs. Recently, trachea has been shown to secrete Dpp, which contributes to the regulation of intestinal homeostasis through the BMP pathway [30], indicating that interorgan communication can provide niche signals. Our results shed new light on gut–neuron interaction in regulating posterior midgut homeostasis.

Hh signaling was previously reported to have important roles in the gastrointestinal system [22–27], but the mechanisms remain obscure. Intestine is a dynamically fine-controlled system. It is not surprising that there is a feedback loop from the differentiated cells to the stem cell compartment, which might depend on epithelial–other organ interactions. For example, this feedback loop in mammals depends on epithelial–mesenchymal interactions. In our study, we found that downregulation and upregulation of Hh ligand in ECs caused similar phenotypes as did neuronal Hh signaling. Together with that neuronal Ci acts downstream of Hh ligand secreted by ECs, these results indicate that Hh ligand might have a role in the feedback loop connecting ECs and neurons. Consistent with our results, Li et al. [28] also reported that hh RNAi driven by 24BGal4 and myoIAGal4 promotes proliferation rate in intestine. However, they also reported that downregulation of hh in Drosophila whole body using tubGal4>hh RNAi caused a reduction of intestinal progenitor cells and a decreased proliferation rate of ISCs. This might be due to that different sources of Hh could perform different functions, a possibility that needs to be further tested. Recently, it is reported that in Drosophila larvae, the intestine responds to nutrient availability by regulating production of a circulating lipoprotein-associated form of the signaling protein Hh. Here, Hh ligand also acts as a lipoprotein-associated endocrine hormone, coordinating the response of multiple tissues to nutrient availability [31]. Together with our finding that total loss of Hh ligand results in different phenotypes from EC loss of Hh ligand, suggests that the role of Hh signaling in the regulation of intestinal homeostasis is far more complicated than we have known. Hh signaling is involved in the response to starvation and stress situation, in both of which Hh had a role more likely involved in the systematic control of intestinal homeostasis.

We tried to detect the cell body of neurons that spread over the posterior intestine; however, no precise conclusion can be made at this point. Since a connection between enteric neurons and corpus cardiacum/hypocerebral ganglion has been reported [32], we traced neurons from corpus cardiacum/hypocerebral ganglion and did find a connection between corpus cardiacum/hypocerebral ganglion and brain (data not shown). In addition, we found that Ci, Smo and Ptc are located in brain (Supplementary Figures S11C–E). Interestingly, ptclaZ, a classic reporter gene of Hh signaling, is downregulated in brain after DSS treatment (Figures 5i and j). This result further suggests that neurons, serving as a mediator between gut and brain, might be involved in the systematic control of intestinal homeostasis, and neuronal Hh signaling is important in this process. We also found that although innervations only occur in the posterior intestine, the proliferation rate change caused by abnormality of neuronal ci RNAi is not limited to this region. This observation further supports that neurons might contribute to the systematic control of intestinal homeostasis.

Apparently, there exist alternative interpretations for how neurons regulate intestinal homeostasis. For example, ablation of neurons might influence food intake or intestinal peristalsis, and both of them may impact intestinal epithelial renewal. In this regard, we tested prandial behavior in the capillary feeder assay [33], as well as digestion ability of flies by dissecting intestinal tracts. The results showed that ablation of neurons caused about half decrease of food intake accompanied by decreased digestion ability (Supplementary Figures S12A, B and E). These results suggest multiple roles of neurons in intestine. As one of the neuronal mechanisms regulating intestinal homeostasis, neuronal Hh signaling did not alter food intake or intestinal peristalsis (Supplementary Figures S12A–D), but may rather directly acts on intestinal homeostasis. A full mechanistic understanding of how neurons regulate intestinal homeostasis warrants further investigation.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks and genetics

elavGal4, ptcGal4, hhGAL4, ciGal4 and myoIAGal4 flies have been previously described (Flybase) [34–39]. ci RNAi (NIG, no. 2125R-1), ptc RNAi (NIG, no. 2411R-1), smo RNAi (NIG, no. 11561R-1) flies were obtained from NIG. The efficiency of RNAi lines has been tested in our previous studies [36]. hh RNAi fly was a gift from Dr Haiyun Song. UAS-ci103, UAS-grim, UAS-hid, and UAS-rpr flies were generated using pUAST vector by standard P-element-mediated transformation.

Fly husbandry

Flies were fed with standard media at 25 °C. Larvae with tubGal80ts for experiments were raised to adults at 18 °C in humidity controlled incubators, as under this condition Gal4 activity is suppressed and transgenes or RNAis are not expressed. After eclosion, flies were cultured at 29 °C for 7 days (neuron ablation experiments), 10 days (neuronal Hh signaling block or activation experiments) or 14 days (detect neuron morphology experiments without further explanation) before dissection, under this condition Gal4 suppression is released and transgenes or RNAis expression are activated.

Immunofluorescence staining

Female flies were used for gut immunostaining in all experiments. Primary antibodies used in this study include mouse anti-Arm (1:500, DSHB, Iowa City, IA, USA), mouse anti-Delta (1:100, DSHB), mouse anti-Prospero (1:2 000, DSHB), rabbit anti-PH3 (1:2 000, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), mouse anti-GFP (1:1 000; Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), rabbit anti-Pdm-1 (1:2 000; a gift from Dr Xiaohang Yang, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China), mouse anti pSTAT (1:200; a gift from Dr Xinhua Lin, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China), rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (1:500, Cappel) and mouse anti-BrdU (1:100, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Confocal imagings were collected using a Leica TCS system (Leica, Frankfurt, Germany) and processed by Adobe Photoshop and ImageJ (San Jose, CA, USA).

Brdu tracing

Female adult flies, 3–5 days old, were used for Brdu-tracing experiments. Flies were cultured in an empty vial containing a piece of 2.5×3.75 cm chromatography paper (Fisher) wet with 5% sucrose solution as feeding medium. Flies were fed with BrdU (0.2 mg ml−1, Sigma, Louisville, MO, USA)) dissolved in 5% sucrose for 3 days at 29 °C, and then cultured with standard medium for another 3 days before dissection.

Cell counting

Mitotic indices were quantified by counting PH3+ cells in >5 midguts of the indicated genotype, time point or condition, and are presented as means±s.d. Confocal images (enlargement factor 10×40) of posterior midgut were used for analysis of cell percentage. Cell number was the average of basal layer and apical layer.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from midguts of 8–10-day-old female flies using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting RNA was used to synthesize cDNA by ReverTra Ace synthesis kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Real-time PCR was performed using ABI7500 System with SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (Toyobo) reagent. rpl32 was used as a normalization control for all of the PCRs.

Transmission electron microscopy

The posterior gastrointestinal tract fragments were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 4 h at room temperature (RT) and then in 1% osmium tetroxide overnight at 4 °C. The fixed midgut fragments were dehydrated through an alcohol series and embedded in Epon812 Resin at 60 °C for 48 h. Ultrathin sections (75 nm) were collected in copper grids. The grids were stained in 2% uranyl acetate for 40 min and in lead citrate for 8 min orderly. The samples were examined under electron microscope (FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

Immuno-TEM

The posterior gastrointestinal tract was taken and cut into small fragments (1 mm), and then fixed in 4% formaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde for 4 h at RT. The fixed midgut fragments were dehydrated through an alcohol series and embedded in LR-White Resin (Sigma) at 50 °C for 24 h. Ultrathin sections (75 nm) were collected in nickel grids with a single slot. After blocked with 5% BSA in PBST (1× PBS, pH 7.4, 0.05% Tween-20), the grids were incubated with rabbit anti-HRP antibody (1:500) for 2 h at RT. The grids were washed with PBST (3×15 min) and then were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 10 nm colloidal gold (1:60, Sigma) for 2 h at RT. After three times (3×15 min) wash with PBST, the samples were stained with 2% uranyl acetate solution for 20 min at RT. After that, samples were examined under electron microscope (FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin).

Distance measurement

Longitudinal section of intestines was used for distance measurement. ECs, EEs were randomly picked up. The distances between the chosen cell and the nearest intestinal progenitor cells or synapses were measured. To measure the distances between intestinal progenitor cells and synapses, intestinal progenitor cells were randomly picked up and the distances between the chosen cell and the nearest synapses were measured.

DSS treatment

Female adult flies (3/4 day old) were used to perform DSS-treated feeding experiments. Flies were cultured in instant food made with water or 3% DSS (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) for 3 days at 29 °C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Jin Jiang, Chao Tong, Huaqi Jiang, Haiyun Song, Xiaohang Yang, Xinhua Lin and Dahua Chen, Yan Li and DSHB, Cappel, BD Biosciences, VDRC, NIG and the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks and reagents. We also thank Drs Fude Huang and Ping Hu for discussions and comments on the manuscript. We are particularly grateful to Dr Chi-Chung Hui for suggestions and comments on the manuscript. We also thank the grant support from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: 2011CB943902), the `Strategic Priority Research Program' of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA01010405), and also from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171414, 31371492, 31301187).

References

- Casali A, Batlle E. Intestinal stem cells in mammals and Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell 2009; 4: 124–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biteau B, Hochmuth CE, Jasper H. Maintaining tissue homeostasis: dynamic control of somatic stem cell activity. Cell Stem Cell 2011; 9: 402–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micchelli CA, Perrimon N. Evidence that stem cells reside in the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. Nature 2006; 439: 475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlstein B, Spradling A. The adult Drosophila posterior midgut is maintained by pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2006; 439: 470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulas S, Conder R, Knoblich JA. The Par complex and integrins direct asymmetric cell division in adult intestinal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 11: 529–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien LE, Soliman SS, Li X, Bilder D. Altered modes of stem cell division drive adaptive intestinal growth. Cell 2011; 147: 603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Navascues J, et al. Drosophila midgut homeostasis involves neutral competition between symmetrically dividing intestinal stem cells. EMBO J 2012; 31: 2473–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neunlist M, et al. The digestive neuronal-glial-epithelial unit: a new actor in gut health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10: 90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbransen BD, Sharkey KA. Novel functional roles for enteric glia in the gastrointestinal tract. Nature reviews. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 9: 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal M, Sandoval H, Zhang K, Bayat V, Bellen HJ. Probing mechanisms that underlie human neurodegenerative diseases in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet 2012; 46: 371–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cognigni P, Bailey AP, Miguel-Aliaga I. Enteric neurons and systemic signals couple nutritional and reproductive status with intestinal homeostasis. Cell Metab 2011; 13: 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talsma AD, et al. Remote control of renal physiology by the intestinal neuropeptide pigment-dispersing factor in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 12177–12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Edgar BA. EGFR signaling regulates the proliferation of Drosophila adult midgut progenitors. Development 2009; 136: 483–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan LY, Jan YN. Antibodies to horseradish peroxidase as specific neuronal markers in Drosophila and in grasshopper embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982; 79: 2700–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, Mao Z, Davis RL. Spatiotemporal gene expression targeting with the TARGET and gene-switch systems in Drosophila. Sci STKE 2004; 2004: pl6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SJ, et al. Hid, Rpr and Grim negatively regulate DIAP1 levels through distinct mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4: 416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, et al. Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell 2009; 137: 1343–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham PW, Nakano Y, Seger C. Mechanisms and functions of Hedgehog signalling across the metazoa. Nat Rev Genet 2011; 12: 393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Hui CC. Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev Cell 2008; 15: 801–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Therond PP. The mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling and its roles in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013. 14: 416–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalderon D. Transducing the hedgehog signal. Cell 2000; 103: 371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brink GR, et al. Indian Hedgehog is an antagonist of Wnt signaling in colonic epithelial cell differentiation. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dop WA, et al. Depletion of the colonic epithelial precursor cell compartment upon conditional activation of the hedgehog pathway. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 2195–2203 e2191-2197 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolterud A, et al. Paracrine Hedgehog signaling in stomach and intestine: new roles for hedgehog in gastrointestinal patterning. Gastroenterology 2009; 137: 618–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski C, et al. Indian hedgehog regulates intestinal stem cell fate through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during development. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 893–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison BB, et al. Epithelial hedgehog signals pattern the intestinal crypt-villus axis. Development 2005; 132: 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LC, et al. Disruption of hedgehog signaling reveals a novel role in intestinal morphogenesis and intestinal-specific lipid metabolism in mice. Gastroenterology 2002; 122: 469–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, et al. Debra-mediated ci degradation controls tissue homeostasis in Drosophila adult midgut. Stem Cell Rep 2014; 2: 135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amcheslavsky A, Jiang J, Ip YT. Tissue damage-induced intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell 2009; 4: 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang Y, Han L, Shi L, Lin X. Trachea-derived dpp controls adult midgut homeostasis in Drosophila. Dev Cell 2013; 24: 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenfels J, et al. Production of systemically circulating Hedgehog by the intestine couples nutrition to growth and development. Genes Dev 2014; 28: 2636–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cognigni P, Bailey AP, Miguel-Aliaga I. Enteric neurons and systemic signals couple nutritional and reproductive status with intestinal homeostasis Sup. Cell Metab 2011; 13: 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ja WW, et al. Prandiology of Drosophila and the CAFE assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 8253–8256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DM, Goodman CS. Ectopic and increased expression of Fasciclin II alters motoneuron growth cone guidance. Neuron 1994;13: 507–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Tong C, Jiang J. Hedgehog regulates smoothened activity by inducing a conformational switch. Nature 2007; 450: 252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, et al. Ter94 ATPase complex targets k11-linked ubiquitinated ci to proteasomes for partial degradation. Dev Cell 2013; 25: 636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micchelli CA, The I, Selva E, Mogila V, Perrimon N. Rasp, a putative transmembrane acyltransferase, is required for Hedgehog signaling. Development 2002; 129: 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, et al. Brahma is essential for Drosophila intestinal stem cell proliferation and regulated by Hippo signaling. eLife 2013; 2: e00999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, et al. Bantam is essential for Drosophila intestinal stem cell proliferation in response to Hippo signaling. Dev Biol 2013; 385: 211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.