Abstract

Objective

As the population ages, the incidence of heart valve disease (HVD) is increasing. The aim of treatment is to improve prognosis and quality of life. Standard surgical treatment is being superseded by new catheter-based treatments, many of which are as yet unproven. The need for appropriate instruments to measure quality of life in patients receiving treatment for HVD has therefore never been greater.

Methods

In this prospective observational study, a generic instrument, Euroqol, and a disease-specific one (Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire—MLHFQ) were, for the first time, formally tested before and after surgery in 84 patients with HVD who completed their treatment. Patients were interviewed on the night before surgery and 6–12 weeks after being discharged. Instruments were tested for validity, reliability, responsiveness, sensitivity and interpretability.

Results

Both Euroqol and MLHFQ registered significant improvements in patients' health. Tests for validity were significantly positive for both Euroqol and MLHFQ. Tests for reliability and responsiveness were very positive for MLHFQ, less so for EQ-5D. There was a moderate ceiling effect in the postoperative Index scores of Euroqol and a moderate floor effect in MLHFQ.

Conclusions

Both instruments together performed very well in assessing the health of patients undergoing surgical treatment of HVD. As the incidence of HVD increases and therapeutic options increase, measurement of PROMS using these two instruments should become a matter of routine.

Keywords: CARDIAC SURGERY, QUALITY OF CARE AND OUTCOMES

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

The incidence of heart valve disease is increasing as the population ages.

The need for percutaneous treatments of heart valve disease is likely to increase dramatically.

There are insufficient published data on quality of life assessment of the effect of heart valve disease and their treatments.

There are no published data on the formal assessment of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS) instruments in this population of patients.

What does this study add?

Euroqol and Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) perform very well as instruments for assessing quality of life in patients with heart valve disease undergoing surgery.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Commissioners paying for any treatment of patients with heart valve disease should insist that PROMS (specifically Euroqol and MLHFQ) should be measured routinely.

PROMs measurement with Euroqol and MLHFQ should be part of any publication looking at the effectiveness of treatments of patients with heart failure.

Introduction

Background

With an ageing population, the incidence of significant heart valve disease is increasing rapidly. The mainstay of treatment for these patients is open heart surgery—specifically heart valve replacement or repair. Although effective, open heart surgery is associated with significant morbidity, which may limit its usefulness in the elderly patient.1–3

In recent years, a number of percutaneous catheter-based treatments have become available. As patients get older and associated morbidities increase, demand for these new costly treatments will also undoubtedly increase. The efficacy of many of these treatments, however, remains unproven.4

The main objectives of any treatment of heart valve disease are to improve quality of life and survival. As the population ages and therapeutic options increase, the need for valid Quality of Life Questionnaires to assess and compare treatments of heart valve disease has never been greater.1–3

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs or PROs in the USA) are instruments used to measure quality of life. They are used to measure the impact illness has on patients' lives as well as the effect and efficacy of treatments.5 6

PROMs can be generic—assessing key aspects of the effect of general health—or disease-specific, assessing health-related quality of life in relation to a specific disease.5 7–12 Although PROMS in patients with heart valve disease have been measured as part of either a study of patients with heart failure14 or of patients undergoing heart surgery in general, the performance of PROMS instruments has never been formally evaluated in this particular population of patients.

Objectives

In this prospective observational clinical study, we have formally tested two PROMS instruments in patients undergoing surgery for specifically heart valve disease. The first is generic, EuroQol (EQ-5D), and the other disease-specific, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ).3 7 13–17

Methods

PROMS instruments are formally evaluated for their usefulness within an intended population by measurement of their validity, reliability, responsiveness, sensitivity and interpretability.9 18–20

Validity is the ability of the questionnaire to accurately measure the intended outcome, that is, those who score poorly are indeed in poor health. Three different aspects of validity are measured: content, construct and criterion.

Content validity refers to appropriateness and acceptability of the questions.

Construct validity measures the ability of different domains of the questionnaire to differentiate between different levels of (ill) health and whether those in poorer health are scoring themselves appropriately.

Criterion validity assesses whether the PROMS results correlate with previously accepted measures (concurrent) and how well PROMS scores can predict outcome after treatment (predictive).9 18–21

Reliability: of a PROMS instrument measures the consistency of the results if the questionnaire is repeated in the same population. This can be measured by test–retest, that is, applying the test repeatedly in the same population whose health has not altered. If test–retest is not possible, internal consistency is assessed. This measures correlation between items that measures similar quality of life domains. A Cronbach’s α (measure of internal consistency) of 0.7–0.9 is evidence of strong internal consistency and therefore reliability.9 18–20

Responsiveness: of a PROMS instrument assesses whether the instrument can detect changes over time that matter to patients. It is measured using the Cohen effect size. A Cohen effect size of 0.8 or more is considered large.9 18–20 22

Interpretability: of an instrument is an assessment of whether the measured change is clinically significant and is specific to the condition and intervention being investigated. It is evaluated using the minimum clinically important difference (MCID). This is the smallest change in score associated with a significant improvement in their health.19 23 24

Study design

Prospective observational clinical study

Study participants and setting

Adults aged 18 years or older, who were scheduled to undergo heart valve surgery for a diagnosis of significant heart valves disease (stenosis, regurgitation or both) at the South Yorkshire Cardiothoracic Centre in Sheffield, England, were eligible for the study.

Patients underwent heart valve surgery between October 2012 and February 2013. Inclusion criteria were proficiency in English, sufficient cognitive capacity and availability for telephone follow-up.

The Department of Clinical Effectiveness at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals National Health Service Trust gave approval for this service review. Patients were given an information leaflet several days before surgery and consented for the study just prior to the preop questionnaire.

Data source

Patients completed the preoperative questionnaire face to face with the investigator on the night before surgery. Six to 12 weeks after surgery, they completed the postoperative questionnaire by telephone or by post if this was not possible.5 6 21 25 Demographic data as well as basic information on the patients' diagnosis and treatment were collected from the cardiac surgery database.

Study size

A formal power calculation was not performed. The number of patients included in the study was determined by time available (9 months) to the research student (C H)

Variables—the HQoL instruments

Generic

EQ-5D (EuroQol) is the most common generic HQoL instrument used in Europe. It provides a single index score of a patient’'s health status. It has two components. In the first, the patient has to score 1 (the best) to 3 (the worst) in five domains—usual activity, mobility, anxiety or depression, pain and discomfort, and self-care. The score thus provides a five digit code of health status example 12321. The code is used to create an index score using a weighted system derived from a table of figures generated from a UK population sample (figure 1).

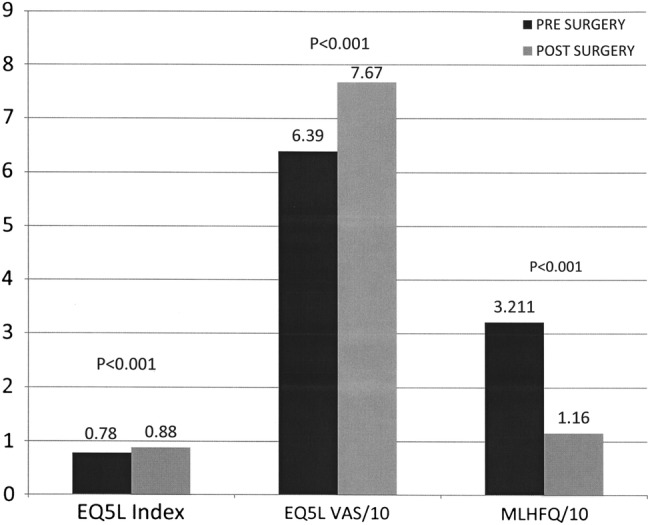

Figure 1.

Change in PROMS score with surgery. PROMS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measures; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; VAS, visual analogue score.

The second component of Euroqol is a visual analogue scale (VAS) of the patient overall health status ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 being the worst health state imaginable and 100 being the best.7 12–14 26

Disease-specific

The Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire (MLHFQ) is a 21 item questionnaire which measures three aspects of the health-related quality of life—physical, emotional and socioeconomic table 1. Patients are asked to score the effect of their illness on a particular aspect of their lives over the past month, on a scale of 0–5. 0 represents no effect, whereas 5 represents a large effect. The lower the score, the better the patient’'s health. A score of less than 24 signifies good health, 24–45 moderate health and 45–105 (maximum) poor health. One of the items of the MLHFQ relating to medical costs was not used. The healthcare system in the UK is universally available, funded through general taxation and free at the point of care.

Table 1.

List of questions in the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire

| The following questions ask how much your heart failure (heart condition) affected your life during the past month (4 weeks). After each question, circle the 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 to show how much your life was affected | |

| If a question does not apply to you, circle the 0 after that question. Did your heart failure prevent you from living as you wanted during the past month (4 weeks) by | |

| - No (0) Very Little (1) Very Much(5) | |

| 1. Causing swelling in your ankles or legs? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 2. Making you sit or lie down to rest during the day? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 3. Making your walking about or climbing stairs difficult? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 4. Making your working around the house or yard difficult? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 5. Making your going places away from home difficult? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 6. Making your sleeping well at night difficult? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 7. Making your relating to or doing things with your friends or family difficult? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 8. Making your working to earn a living difficult? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 9. Making your recreational pastimes, sports or hobbies difficult? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 10. Making your sexual activities difficult? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 11. Making you eat less of the foods you like? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 12. Making you short of breath? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 13. Making you tired, fatigued or low on energy? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 14. Making you stay in a hospital? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 15. Costing you money for medical care? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 16. Giving you side effects from treatments? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 17. Making you feel you are a burden to your family or friends? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 18. Making you feel a loss of self-control in your life? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 19. Making you worry? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 20. Making it difficult for you to concentrate or remember things? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 21. Making you feel depressed? | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

The total potential score for the study was therefore 100.

A change in the score of five or more (with treatment) is regarded as significant.

Educational licenses to use both instruments in this academic study (Bachelor of Medical Science Thesis) were obtained from the Euroqol Foundation and the University of Minnesota.3 14 15 17 26 27

NYHA status (New York Heart Association Class of Cardiac-related Dyspnoea)

This was assessed at the same two time points. Class ranged from I (no symptoms) to IV (severe limitation with symptoms at rest).

Statistical methods

Change in QoL

Pre and postoperative scores were compared using Paired t test.22

Instrument effectiveness

Content validity was assessed qualitatively by assessing whether PROMs are credible, sensible and comprehensive.

Construct validity—analysis of variance of the PROMS scores of different groups ranked by their NYHA status (New York Heart Association Class of Cardiac-related Dyspnoea)—Kruskall-Wallis.

Concurrent validity—calculation of correlation between all PROMS scores (pre and postop) and respective NHYA scores for both instruments—Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

Predictive criterion—calculation of correlation between preoperative PROM scores and difference in scores achieved after surgery for both instruments—Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

Reliability—calculation of correlation of individual items within a domain; items scoring the same HRQoL domains are expected to be highly correlated—Cronbach's α

Responsiveness—the mean change in score after treatment divided by the SD of the baseline scores—Cohen effect size

Sensitivity—estimation of floor and ceiling effects—percentage scoring at the highest and lowest possible scores.

Interpretability—measurement of MCID—the difference between postoperative scores of patients who felt ‘much better’ and those who felt ‘no different’21 22 24

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS package.

Results

Participants

Of the 98 eligible patients, 92 were recruited and of these 84 completed the study.

Descriptive data

Patient and procedure characteristics are outlined in table 2.

Table 2.

Patient and procedure characteristics

| Age (mean, SD, range) | 69.6±10.4, 40–88 |

| Male | 72% |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 48% |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 41% |

| Elective | 81% |

| Duration of symptoms in months, (median, IQR, range) | 24, 38, 0.5–144 |

| Single valve disease and intervention | 89% |

| Type of valve disease | |

| Aortic stenosis | 57% |

| Mitral regurgitation | 13% |

| Aortic regurgitation | 8% |

| Mixed aortic pathology | 8% |

| Mitral stenosis | 1% |

| Mixed mitral pathology | 1% |

| Multiple valve disease | 12% |

| Type of surgery for those with single valve disease | |

| Replacement | 53% |

| Replacement and other | 40% |

| Repair | 4% |

| Repair and other | 3% |

Main results

Change in QoL score

EQ5L

Index score pre 0.78 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.83)

Index score post 0.88 (0.84 to 0.92)

p<0.001

VAS score pre 63.9 (59.5 to 68.3)

VAS score post 76.7 (72.6 to 80.7)

p<0.001

MLHFQ

Pre score 32.11 (27.4 to 36.78)

Post Score 11.6 (7.79 to 15.4)

p<0.001

Instrument effectiveness

EQ5D

Validity:

Construct, see table 3

Concurrent criterion—Spearman rank correlation coefficient for index scores—0.26 (p=0.017), for VAS scores—0.33 (p=0.001)

Predictive criterion—Spearman rank coefficient for index score 0.74 (p<0.001) and for VAS scores—0.33 (p=0.001)

Reliability—Cronbach's α 0.68 (≥0.7)

Responsiveness—Cohen effect size for index scores—0.46, for VAS scores 0.64.

Sensitivity—no floor effects pre (1.2% index and VAS scores) or postoperative (1.2% index and VAS scores) Mild ceiling effect in preop index scores (39.3%) and moderate ceiling effect in the postoperative index score (63.1%)

Interpretability—MCID for index scores 0.125 (95% CI 0.0056 to 0.2412) p=0.001

Table 3.

Results of construct validity of Euroqol and MLHFQ using NHYA status as a comparator

| NYHA | EQ-5D INDEX SCORE (mean, 95% CI) | EQ-5D VAS SCORE | MLHFQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| NYHA 2 | 0.82 (0.766 to 0.88) | 70 (65.2 to 75) | 21 (16.7 to 21.21) |

| NYHA 3 | 0.77 (0.692 to 0.848) | 57 (49 to 65.2) | 40.4 (33.01 to 47.85) |

| NYHA 4 | 0.57 (0.33 to 0.815) | 51 (31.1 to 72.5) | 60 (43.78 to 77.12) |

| p Value | 0.056 | 0.007 (ANOVA) 0.02 (Kruskal-Wallis) |

<0.001 |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; MLHFQ,Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; NYHA, New York Heart Association; VAS, visual analogue score.

MLHFQ

Validity:

Construct, see table 3

Concurrent criterion—Spearman rank correlation coefficient—0.54 (p<0.001)

Predictive criterion—Spearman rank correlation coefficient—0.54 (p<0.001)

Reliability—Cronbach's α 0.914

Responsiveness—Cohen's effect size 0.95.

Sensitivity—Percentage scoring 0 for the 20 questions—3.6%-85.7%. Percentage scoring 5–3.6%—28%, suggesting a floor effect

Discussion

Measurement of PROMS or the formal assessment of the effect of disease and its treatment on a patient's quality of life is becoming increasingly important in modern healthcare. They are used as an assessment of efficacy of treatments as well as an outcome measure to assess performance of institutions who deliver the treatment.5 6

Formal assessment of PROMS in patients undergoing major joint replacement, varicose vein surgery and hernia repair is now routine for all patients being treated for these conditions in the UK National Health Service.5 6 A pilot study has examined the use of PROMS undergoing percutaneous and surgical revascularisation of significant coronary artery disease.28

Owing to an ageing population, the incidence of significant heart valve disease is increasing. Ten per cent of all humans aged 80 or older will have significant aortic stenosis, the most common valve dysfunction in the developed world.29 Asymptomatic patients can live a long time with significant heart valve dysfunction. Once symptoms set in, however, patients quickly become disabled with symptoms of breathlessness, chest pain and fluid retention, and their prognosis rapidly worsens if the valve disease is left untreated.30

Until fairly recently, the mainstay of treatment has been open heart surgery. Although effective, and despite the recent increase in ‘minimally-invasive’ techniques, surgery remains a treatment associated with significant morbidity and mortality. This becomes more prominent in older patients. In addition, many patients do not seem to get the presumed benefit from undergoing major heart surgery.29 30

Over the past 5 years, there has been a rapid increase in the uptake of non-surgical catheter-based solutions, most common of which is the transcutaneous aortic implantation (TAVI) (TAVR replacement in the USA) procedure. A number of devices for the treatment of mitral valve regurgitation (the second most common valve dysfunction in the developed world) are just over the horizon. These devices are very expensive and many are of unproven worth. In a world of cash-strapped healthcare systems, evidence-based means of assessing the effect of disease and its treatment are urgently required.

The standard for assessing PROMS in any condition is to use two instruments—a generic one and a disease-specific one.6

Euroqol is by far the most commonly used generic instrument in Europe. It has been shown in many studies of patients with various conditions to be an effective way of assessing quality of life before and after treatment.7 12–14 26

A comprehensive formal review of PROMS instruments in patients receiving medical treatment for heart failure by the PROMS group at Oxford University concluded that the Euroqol and MLHFQ were the most appropriate to measure quality of life in this group of patients.14

Key results

In this study, we examined the performance of Euroqol and MLHFQ PROMS in patients receiving surgical treatment for heart valve disease. This is the first study to formally evaluate any PROMS instruments in this population of patients.

We have demonstrated a significant improvement in health status using Euroqol. The instrument has been shown to be significantly valid but performed less well in the assessment of reliability and responsiveness. A Cronbach score of 0.68 in the reliability test was only just below the significant figure of 0.7 or higher. Since this study looked at completed responses from only 87 patients, it is highly likely that a more appropriately powered study would have come up with a higher score.3 5 6 9 17–22

The performance of the MLHFQ instrument was very impressive, even though the number of participating patients was small. It showed significant improvements in health status after surgery and tests of validity, reliability and responsiveness were all highly significant with p values of <0.001.3 9 17–22

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study, namely the relatively small number of patients studied and the fact that the postoperative questionnaire was only conducted once at 6 weeks. The other obvious limitation is that the featured treatment did not include percutaneous options.

Interpretation

Nonetheless, we have shown that Euroqol and MLHFQ fit the bill very nicely for the assessment of the effect of heart valve disease and its treatment on patients' quality of life.

Generalisability

The case for routine measurement of PROMS is strong. With the inevitable rapid expansion in percutaneous treatments and its associated costs, occurring in the near future, we would urge all commissioners to require providers to adopt these instruments in the management of patients undergoing treatment of heart valve disease as a matter of routine.5 6

Measurement of PROMS using Euroqol and MLHFQ should also be part of every research study looking at the effectiveness of treatments in patients with heart valve disease.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Norman Briffa at @chestcracker

Contributors: This work was undertaken as part of an intercalated Bachelor of Medical Science Degree of CH. CH collected and analysed the data and wrote the first draft. NB supervised CH and wrote the final draft of the paper.

Funding: Funding for this study was obtained through the Sheffield Hospitals Charitable Trust.

Competing interests: NB is treasurer to the British Heart Valve Society.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data gathered in this study were used in the analysis and preparation of this paper.

References

- 1.d’ Arcy JL, Prendergast BD, Chambers JB et al. Valvular heart disease: the next cardiac epidemic. Heart 2011;97:91–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malhotra A. The Changing Burden of Valvular Heart Disease 2012. http://www.bcs.com/pages/news_full.asp?NewsID=19792059 (accessed 8 May 2013).

- 3.Supino PG, Borer JS, Franciosa JA et al. Acceptability and psychometric properties of the Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire among patients undergoing heart valve surgery: validation and comparison with SF-36. J Card Fail 2009;15:267–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Georgiadou P, Kontodima P, Sbarouni E et al. Long-term quality of life improvement after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am Heart J 2011;162:232–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013;346:f167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browne J, Jamieson L, Lewsey J et al. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in elective surgery: report to the Department of Health London: Department of Health Services Research and Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2007. http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/php/hsrp/research/proms_report_12_dec_07.pdf (accessed 22 Apr 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvert MJ, Freemantle N. Use of health- related quality of life in prescribing research. Part 1: why evaluate health- related quality of life? J Clin Pharm Ther 2003;28:513–21. 10.1046/j.0269-4727.2003.00521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickey A, Barker M, McGee H et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in older patient populations: a review of current approaches. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:971–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keszei AP, Novak M, Streiner DL. Introduction to health measurement scales. J Psychosom Res 2010;68:319–23. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPhail SM, Bagraith KS, Schippers M et al. Use of condition-specific patient-reported outcome measures in clinical trials among patients with wrist osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Adv Orthop 2012;2012:273421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patrick DL, Deyo RA. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care 1989;27S217–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brazier J, Roberts J, Tsuchiya A et al. A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Econ 2004;13:873–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The EuroQol Group. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackintosh A, Gibbons E, Fitzpatrick R. A structured review of Patient- Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) for heart failure: report to the department of health Oxford: Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Group, University of Oxford, 2009. phi.uhce.ox.ac.uk/pdf/PROMs_Oxford_HeartFailure_17092010.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rector TS, Kubo SH, Cohn JN. Patient's self-assessment of their congestive heart failure- part 2: content, reliability and validity of a new measure, the Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire. Heart Fail 1987:198–209. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holland R, Rechel B, Stepien K et al. Patients’ self-assessed functional status in heart failure by New York heart association class: a prognostic predictor of hospitalizations, quality of life and death. J Card Fail 2010;6:150–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spaziano M, Carrier M, Pellerin M et al. Quality of life following heart valve replacement in the elderly. J Heart Valve Dis 2010;19:524–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Testa MA, Simonson DC. Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. N Engl J Med 1996;334:835–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: using quality of life measure in the clinical setting. BMJ 2001;322:1297–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson H, Keating J. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): how should I interpret reports of measurement properties? A practical guide for clinicians and researcher who are not biostatisticians. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:792–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labelling claims. Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), 2009. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf (accessed 30 Apr 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walters SJ. Choosing a quality of life measure for your study. In: Walters SJ, ed.. Quality of life outcomes in clinical trials and health-care evaluation: a practical guide to analysis and interpretation. Oxford: Wiley, 2009:31–53. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaton DE, Boers M, Wells GA. Many faces of the minimal clinically important difference (MCID): a literature review and directions for future research. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2002;14:109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD et al. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J 2007;7:541–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black N, Jenkinson C. How can patients’ views of their care enhance quality improvement? BMJ 2009;339:202–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowling A. Measuring broader health status. In: Bowling A. ed. Measuring health: a review of quality of life measurement scales. 3rd edn Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2005:75–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heo S, Moser DK, Riegel B et al. Testing the psychometric properties of the Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire. Nurs Res 2005;54:265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroter S, Lamping DL. Coronary revascularisation outcome questionnaire (CROQ): development and validation of a new, patient based measure of outcome in coronary bypass surgery and angioplasty. Heart 2004;90:1460–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mikaljevic T, Sayeed MR, Stamou SC et al. Pathophysiology of aortic valve disease. In: Cohn LH, ed.. Cardiac surgery in the adult. 3rd edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008:825–40. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonow RO, Otto CM. Valvular heart disease. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP et al. eds. Braunwald's heart disease a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 9th edn Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2012:1468–539. [Google Scholar]