Abstract

Aims and Objectives:

The aim of this study was to analyze and compare the effects of tobacco on salivary pH between tobacco chewers, smokers and controls.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 60 subjects (males and females) aged 25–40 years, were divided equally into three groups: Tobacco smokers (Group A), chewers (Group B) and controls (Group C). Saliva of each subject was collected under resting condition. Salivary pH was determined using the specific salivary pH meter.

Results:

The mean (±standard deviation) pH for Group A was 6.75 (±0.11), Group B was 6.5 (±0.29) and Group C was 7.00 (±0.28) after comparison. The significant results showed lower salivary pH in Groups A and B as compared to controls. Salivary pH was lowest in Group B compared to Group A and Group C.

Conclusion:

This study indicates that a lower (acidic) salivary pH was observed in tobacco users as compared with control. These alterations in pH due to the long-term effect of tobacco use can render oral mucosa vulnerable to various oral and dental diseases.

Keywords: Salivary pH, tobacco, unstimulated saliva

INTRODUCTION

Various clinical and epidemiological evidence have been documented regarding the adverse effects of tobacco on oral health.[1] The adverse effects of cigarette smoking and other forms of tobacco are numerous, use of tobacco has been associated with oral mucosa, gingival diseases and dental alterations.[2]

Saliva is a complex and important body fluid which is very essential for oral health.[3] Saliva plays a critical role in oral homeostasis because it modulates the ecosystem within the oral cavity.[4] Lubrication of the alimentary bolus, protection against virus, bacteria and fungi, buffer capacity, protection and repair of the oral mucosa and dental remineralization are some of the functions of saliva.[5,6,7] Taking this into account, quantitative and/or qualitative alterations in salivary secretion may lead to local (caries, oral mucositis, candidiasis, oral infections, chewing disorders) or extraoral (dysphagia, halitosis, weight loss) adverse effects.[8,9,10] Resting whole saliva is the mixture of secretions and enter the mouth in the absence of exogenous stimuli.[11] Several studies of resting salivary pH estimate a range of 5.5–7.9.[12] The pH of saliva is maintained by the carbonic acid/bicarbonate system, phosphate system and protein system.[13] Saliva is the first biological fluid that is exposed to cigarette smoke, containing numerous toxic compositions responsible for structural and functional changes in saliva.[14] Approximately 600 million people use arecanut worldwide in some form and is the fourth most commonly used psychoactive substance.[15] Arecanut contains four major alkaloids: Arecaidine, arecoline, guvacine and guvacoline. In the presence of lime (calcium oxide which turns to alkali calcium hydroxide in aqueous form), arecoline and guvacoline are largely hydrolyzed into arecaidine and guvacine, respectively.[16] Arecoline is parasympathomimetic while arecaidine lacks it.[16] Areca nut can be chewed as such in raw form, i.e., raw areca nut (RAN) or wrapped in betel leaves (Piper betel), lime and other condiments in a traditional form (referred to as pan, denoted as betel quid [BQ]) and at times tobacco is added to the mixture, i.e., BQ with tobacco. Processed areca nut forms contain chemically or naturally cured arecanut mixed with catechu, saffron, artificial flavoring and sweetening agents (supari) and lime (panmasala) along with tobacco (gutka). The lesser used products in this parts of India include mawa, kahaini and zardha.[17] The main ingredient of tobacco is nicotine and nicotine acts on certain cholinergic receptors in the brain and other organs causing neural activation leading to altered salivary secretion.[18]

There are several studies concerning the effect of chewing tobacco and smoking on salivary secretion, though, long-term effect of tobacco use on pH is still not clear. Due to the paucity of literature on the influence of tobacco use on pH, this study was undertaken to analyze and compare the long-term effect of tobacco on pH in tobacco chewers, tobacco smokers and control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study consists of a total of 60 subjects (males and females) within an age-group of 25–40 years that were equally divided into three groups of 20 subjects each.

Group A: Subjects consuming smoked form of tobacco ([20] 15 males and 5 females)

Group B: Subjects consuming smokeless form of tobacco ([20] 15 males and 5 females)

Group C: Healthy controls ([20] 15 males and 5 females).

Inclusion criteria

Males and females of age between 25 and 40 years

Consumption of tobacco (smoked and smokeless form) for minimum period of around 5 years.

Patients were not aware of the contents of the smokeless form of tobacco.

There are several types of chewing tobacco (smokeless form of tobacco) habits in India featuring use of BQ (fresh betel leaf, fresh areca nut, slaked lime, catechu and tobacco), pan masala (areca nut, slaked lime, catechu, condiments and tobacco), mainpuri (tobacco, slaked lime, areca nut, camphor and cloves), mawa (areca nut, tobacco and slaked lime), khaini (tobacco and slaked lime), gutka (an industrially manufactured food item) and other smokeless tobaccos (mishri, gudhaku, bajjar, etc.).[13]

Exclusion criteria

Age over 40 years

Alcohol consumption

Combination of tobacco (smoke and smokeless form)

History of any other habits (tongue thrusting, mouth breathing, bruxism)

History of trauma to the head and neck

Denture wearers

Pregnant and postmenopausal women

History of radiotherapy

Patients with systemic or salivary gland diseases or under any drug therapy

Patients with any lesion in the oral cavity.[19]

After obtaining informed written consent, a thorough case history was taken followed by careful oral examination. Saliva collection of each subject was done under resting condition. Salivary pH was determined using the specific salivary pH meter. The total period of study was 1 month.

Saliva collection

Saliva collection was carried out between 9:00 am and 12:00 pm to avoid any diurnal variation. Each subject was requested not to drink, eat or perform oral hygiene or chew or smoke 60 min before and during the procedure. Subjects were then asked to be seated on the dental chair and asked to spit 2–3 times in 1 min in a disposable container [Figure 1]. During saliva collection, subjects were instructed not to speak or swallow. Measurement of salivary pH was done immediately after collection using salivary pH meter [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Saliva collection

Figure 2.

Salivary pH meter

Statistics

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Service (SPSS) computer software. Unpaired Student's t-test, one-way ANOVA was applied to assess the pH difference between different groups. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The confidence of 95% was considered, so significance level of 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

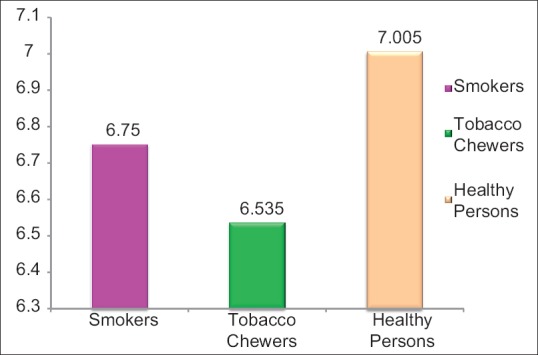

The subjects in our study were present in the age group of 25–40 years. Group A and B subjects consume tobacco for minimum of around 5 years. The mean pH scores of saliva in three distinct groups showed that pH scores were maximum in the control group while it was least in tobacco chewers group [Figure 3, Table 1].

Figure 3.

Graph showing average pH scores of saliva in three groups

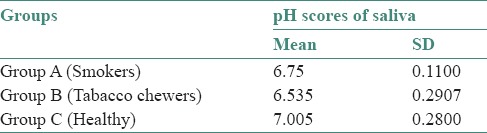

Table 1.

Means, standard deviation of mean of pH scores of saliva in three groups

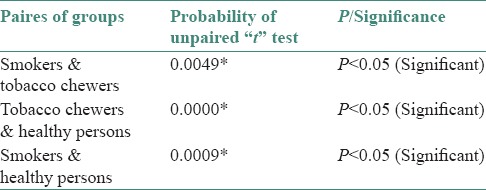

When unpaired t-test was applied for comparison of pH scores of saliva between different groups, results showed a significant difference between pairs of groups at 0.05 level of significance, i.e. (P < 0.05) [Table 2]. Hence, a significant relation was obtained when the mean salivary pH for groups were compared.

Table 2.

Comparison of pH scores of saliva between different pairs of groups (by unpaired t-test)

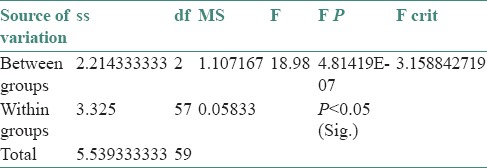

When one way ANOVA test was applied for comparing the pH scores of saliva among three groups, it showed a significant difference in pH scores of saliva among three groups simultaneously at 0 level of significance [Table 3].

Table 3.

One way ANOVA F-table for comparing the pH scores of saliva among three groups

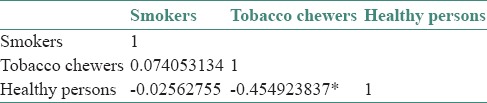

Karl-Pearson correlation coefficient among different groups for pH scores of saliva showed that a strong negative correlation exists between healthy and tobacco chewers for pH scores of saliva [Table 4].

Table 4.

Karl-Pearson correlation coefficient among different groups for pH scores of saliva

DISCUSSION

Saliva is a complex and important body fluid which is very essential for oral health.[3] Saliva is required for protecting the oral mucosa, teeth remineralization, digestion, taste sensation, pH balance and phonation. It includes a variety of electrolytes, peptides, glycoproteins and lipids which have antimicrobial, antioxidant, tissue repair and buffering properties.[20] Saliva is the first biological fluid that is exposed to cigarette smoke, which contains numerous toxic compositions responsible for structural and functional changes in saliva.[14]

In the present study, the mean (±standard deviation [SD]) pH for Group A; 6.75 (±0.11), Group B; 6.5 (±0.29) and Group C; 7.00 (±0.28) when compared. A significant relation was obtained, a lower salivary pH was observed in Groups A and B compared to controls (Group C). Salivary pH was the lowest in Group B compared to Group A and Group C probably because of use of lime in smokeless form, which can react with bicarbonate buffering system by the loss of bicarbonate, turning saliva more acidic. The alteration in electrolytes and ions alters the pH as they interact with the buffering systems of saliva.

Khan et al. also observed a lower salivary pH in smokers than in nonsmokers which was consistent with the findings of the present study.[21] Rooban et al. observed a mean pH of 6.77 in nonchewers and those who chew RAN, the mean pH turns acidic.[13] In contrast, according to Alpana Kanwar et al. The mean (±SD) pH for Group A; 6.8 (±0.1), Group B; 6.7 (±0.1) and Group C; 7.04 (±0.1) when compared and a nonsignificant relation was obtained though, lower salivary pH as was observed in Groups A and B.[19] Reddy et al. also observed no difference in salivary pH between the chewers and nonchewers.[22] This difference could be due to the amount of tobacco, lime and other components. The role of lime in paan and BQ has been a source of concern. Lime (calcium oxide in aqueous forms calcium hydroxide) could cause a free radical injury or the high alkaline content probably reacts with the salivary buffering systems and alters the pH.[23] A salivary pH of 7.0 usually indicates a healthy dental and periodontal situation. At this pH, there is a low incidence of dental decay and little or no calculus. Therefore, stable conditions should basically be found in this environment. A saliva pH below 7.0 usually indicates acidemia (abnormal acidity of the blood). If a chronic condition exists, the mouth is more susceptible to dental decay, halitosis and periodontitis. Chronic acidemia can be a causative factor for a multitude of diseases affecting the whole body.[24]

CONCLUSION

This was a preliminary study having a small sample size and multiplicity of factors. The conclusion of present study is that the long-term use of tobacco especially the smokeless form can cause significant alteration in pH (is more acidic). These alterations in long-term tobacco users can render oral mucosa vulnerable to various oral and dental diseases.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Millar WJ, Locker D. Smoking and oral health status. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73:155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meraw SJ, Mustapha IZ, Rogers RS., 3rd Cigarette smoking and oral lesions other than cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1998;16:625–31. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(98)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rad M, Kakoie S, Niliye Brojeni F, Pourdamghan N. Effect of long-term smoking on whole-mouth salivary flow rate and oral health. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2010;4:110–4. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2010.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson JC, Baum BJ. Salivary enhancement: Current status and future therapies. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1096–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandel ID. The role of saliva in maintaining oral homeostasis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;119:298–304. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1989.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sreebny LM. Saliva in health and disease: An appraisal and update. Int Dent J. 2000;50:140–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonies BC, Ship JA, Baum BJ. Relationship between saliva production and oropharyngeal swallow in healthy, different-aged adults. Dysphagia. 1989;4:85–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02407150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkinson JC, Wu AJ. Salivary gland dysfunction: Causes, symptoms, treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125:409–16. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1994.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ship JA, Pillemer SR, Baum BJ. Xerostomia and the geriatric patient. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:535–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valdez IH, Fox PC. Interactions of the salivary and gastrointestinal systems. II. Effects of salivary gland dysfunction on the gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis. 1991;9:210–8. doi: 10.1159/000171305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrett JR. The proper role of nerves in salivary secretion: A review. J Dent Res. 1987;66:387–97. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choo RE, Huestis MA. Oral fluid as a diagnostic tool. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42:1273–87. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2004.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rooban T, Mishra G, Elizabeth J, Ranganathan K, Saraswathi TR. Effect of habitual arecanut chewing on resting whole mouth salivary flow rate and pH. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:95–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox PC, Ship JA. Salivary gland diseases. In: Greenberg MS, Glick S, editors. Burket's Oral Medicine: Diagnosis and Treatment. 11th ed. Hamilton: BC Decker; 2008. pp. 191–223. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trivedy CR, Craig G, Warnakulasuriya S. The oral health consequences of chewing areca nut. Addict Biol. 2002;7:115–25. doi: 10.1080/13556210120091482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu NS. Effects of betel chewing on the central and autonomic nervous systems. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8:229–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02256596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chadda R, Sengupta S. Tobacco use by Indian adolescents. Tob Induc Dis. 2002;1:111–9. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-1-2-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouquot DJ, Schroeder K. Oral effect of tobacco abuse. J Am Dent Inst Contin Educ. 1992;43:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanwar A, Sah K, Grover N, Chandra S, Singh RR. Long-term effect of tobacco on resting whole mouth salivary flow rate and pH: An institutional based comparative study. Eur J Gen Dent. 2013;2:296–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zappacosta B, Persichilli S, De Sole P, Mordente A, Giardina B. Effect of smoking one cigarette on antioxidant metabolites in the saliva of healthy smokers. Arch Oral Biol. 1999;44:485–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(99)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan GJ, Javed M, Ishaq M. Effect of smoking on salivary flow rate. J Med Sci. 2010;8:221–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy MS, Naik SR, Bagga OP, Chuttani HK. Effect of chronic tobacco-betel-lime “quid” chewing on human salivary secretions. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:77–80. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/33.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nair UJ, Obe G, Friesen M, Goldberg MT, Bartsch H. Role of lime in the generation of reactive oxygen species from betel-quid ingredients. Environ Health Perspect. 1992;98:203–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9298203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baliga S, Muglikar S, Kale R. Salivary pH: A diagnostic biomarker. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:461–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.118317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]