Abstract

Background:

Telomerase is an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase that synthesizes TTAGGG telomeric DNA sequences and almost universally provides the molecular basis for unlimited proliferative potential. The telomeres become shorter with each cycle of replication and reach a critical limit; most cells die or enter stage of replicative senescence. Telomere length maintenance by telomerase is required for all the cells that exhibit limitless replicative potential. It has been postulated that reactivation of telomerase expression is necessary for the continuous proliferation of neoplastic cells to attain immortality. Use of immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a useful, reliable method of localizing the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) protein in tissue sections which permits cellular localization. Although there exists a lot of information on telomerase in oral cancer, little is known about their expression in oral epithelial dysplasia and their progression to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) compared to normal oral mucosa. This study addresses this lacuna.

Aims:

To compare the expression of hTERT protein in oral epithelial dysplasia and OSCC with normal oral mucosa by Immunohistochemical method.

Subjects and Methods:

In this preliminary study, IHC was used to detect the expression of hTERT protein in OSCC (n = 20), oral epithelial dysplasia (n = 21) and normal oral mucosa (n = 10). The tissue localization of immunostain, cellular localization of immunostain, nature of stain, intensity of stain, percentage of cells stained with hTERT protein were studied. A total number of 100 cells were counted in each slide.

Statistical Analysis:

All the data were analyzed using SPSS software version 16.0. The tissue localization, cellular localization of cytoplasmic/nuclear/both of hTERT stain, staining intensity was compared across the groups using Pearson's Chi-square test. The mean percentage of cells stained for oral epithelial dysplasia, OSCC and normal oral mucosa were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results:

The mean hTERT positive cells in the study groups were as follows, 62.91% in normal oral mucosa samples, 77.06% in oral epithelial dysplasia cases, and 81.48% in OSCC. In 61.9% of oral epithelial dysplasia and 65% of OSCC in our study, staining was visualized within the nucleus predominantly in the dot like pattern. There was a statistically significant difference in the nature of nuclear stain between oral epithelial dysplasia and OSCC (P = 0.023).

Conclusions:

Our results suggests that the mean percentage of cells showing hTERT expression steadily increased from normal oral mucosa to oral epithelial dysplasia to OSCC. The steady trend of increase in the percentage of cells was evident in different grades of oral epithelial dysplasia group and OSCC. The nature of hTERT staining did show variations among the three groups and promise to be a potential surrogate marker for malignant transformation. Further studies using IHC on larger sample size and clinical follow-up of these patients will be ascertaining the full potential of hTERT as a surrogate marker of epithelial transformation.

Keywords: Human telomerase reverse transcriptase protein, oral potentially malignant disorders, oral squamous cell carcinoma, telomerase

INTRODUCTION

Oral Leukoplakia is the most common potentially malignant disorder of the oral cavity representing 85% of these lesions.[1] On biopsy, most leukoplakias show histological features of epithelial dysplasia. Unfortunately, the recognition of dysplastic features is subjective and there are wide variations in the degree of inter-examiner agreement and intra-examiner reproducibility in the diagnosis. The reported prevalence of malignant transformation in oral leukoplakia ranges from 5% to 25%.[2]

The presence of epithelial dysplasia is a marker of the malignant potential of oral leukoplakia, 36% of dysplastic oral leukoplakia progressed to squamous cell carcinoma.[2] Squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck is a complex disease that is characterized by clinical, pathological, phenotypically and biologic heterogeneity. Mounting evidence suggests a model of molecular progression from premalignant lesions to invasive disease.[3]

As malignant transformation is difficult to predict, numerous research projects are directed toward identification of surrogate markers of malignant transformation. The possibilities that have been explored include DNA aneuploidy, loss of heterozygosity by microsatellite markers, mutations in p53 protein and increased expression of telomerase activity.[4]

Telomerase is an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase that synthesizes short tandem repeats of TTAGGG telomeric DNA sequences which universally provides the molecular basis for unlimited proliferative potential. Telomerase consists of two essential components: One is the functional RNA component (hTR or hTERC) serving as a template for telomeric DNA synthesis. The other is the catalytic protein (hTERT) with reverse transcriptase activity. As telomeres become shorter with each cycle of replication and reach a critical limit; most cells die or enter stage of replicative senescence. Telomere length maintenance by telomerase is required for all the cells that exhibit limitless replicative potential.[5]

It has been postulated that telomerase reactivation appears to play an important role in the process of cell immortalization, thus promoting the accumulation of genetic abnormalities and increasing genomic instability that contributes to malignant transformation.[6]

Telomerase activity is up-regulated in many tumors and studies have shown that increased telomerase expression is an early event in oral carcinogenesis.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] The aim of our study was to ascertain the expression of hTERT as an indicator of telomerase activity in oral epithelia dysplasia and oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) using immunohistochemistry (IHC) on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The study samples obtained from archival biopsy specimens from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology comprised of oral epithelial dysplasia (n = 21), OSCC (n = 20) and normal oral mucosa (n = 10). Histopathologically confirmed cases of OSCC and oral epithelial dysplasia were included in the study. Site-matched normal control tissues were obtained from noninflamed buccal mucosa during removal of impacted third molar of patients attending the hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects enrolled in the study and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board. All incisional biopsies were performed under local anesthesia (2% lignocaine). Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for further processing. After adequate fixation, tissue were processed and infiltrated with paraffin wax.

Immunohistochemical detection of human telomerase reverse transcriptase protein

Five-micron thickness were obtained from paraffin-embedded tissues and placed on 3-amino propyl triethoxy silane coated slides. The sections were deparaffinised and brought to water. The sections were placed in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6) and antigen retrieval was done using an autoclave at 15 psi for 15 min. The slides were washed in three changes of tris buffer saline solution. Peroxidase and protein blocking were performed with 3% hydrogen peroxide and protein block provided in the secondary kit. The sections were incubated with diluted primary antibody (1:50 hTERT) at room temperature for 1 h. The sections were stained with streptavidin-horse radish peroxidase-biotin method with Biogenex polymer HRP for 30 min to elongate chain and label the enzyme. The sections were treated with diaminobenzidine hydrochloride for 5 min, counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with DPX®. Testis was used as positive control. hTERT staining in tonsil was used as a standard benchmark to evaluate the intensity of staining among the study group.[15]

Histopathological grading

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were used to confirm clinical diagnosis and grade the specimens. OSCC samples were graded as well, moderately or poorly differentiated.[16] Oral epithelial dysplasia samples were histopathologically graded as mild, moderate or severely dysplastic.

Criteria for evaluation of human telomerase reverse transcriptase staining

The following parameters were used to evaluate hTERT staining:[17]

Tissue localization of the stain: hTERT staining was limited either to basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium, extended up to the spinous layer or was seen throughout all the layers of epithelium

Cellular location of the stain: hTERT staining within each cell was either localized to the nucleus or was present both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm

Nature of stain: The pattern of positive hTERT immunostain was both nuclear as well as cytoplasmic. The various types of nuclear staining examined were dot-like (1–3 small discrete dots within the nucleus), granular (>3 coarse dots), smooth (homogenous brown). The cytoplasmic staining was either smooth or Granular.[15,18]

Intensity of stain: Each positive case was allocated numerical scores as no stain (0), mild (1), moderate (2) or intense (3)

Percentage of cells stained was based on the number of positively stained cells per 100 cells examined using ocular grid.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out in the present study wherein comparison of the mean age among the three groups was done using analysis of variance. The tissue localization of stain, cellular location, nature of stain, intensity of stain and the percentage of cells stained were compared among the three study groups using Pearson's Chi-square test. Kappa statistics for the two observers were computed for finding the inter-observer agreement.

RESULTS

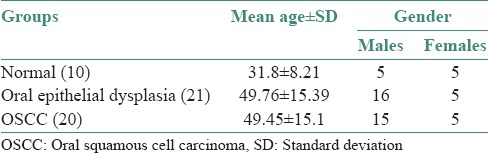

The demographic details of all the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The demographic details of all the patients included in the study

OSCC cases comprised of 45% (9/20) well differentiated, 45% (9/20) moderately differentiated and 10% (2/20) poorly differentiated carcinomas. Of the 21 cases of oral epithelial dysplasia, 19.04% (4/21) of the samples exhibited mild, 52.3% (11/21) moderate and 28.5% (6/21) severe dysplasia.

Of the 21 patients in Group 1, 16 (76.19%) were men and 5 (23.80%) were women. In Group 2, 15 (75%) were men and 5 (25%) women, whereas in Group 3, 5 (50%) were men and 5 (50%) were women.

Human telomerase reverse transcriptase staining characteristics

Oral epithelial dysplasia

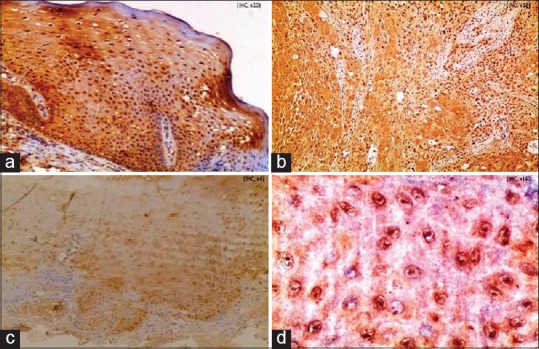

The histopathological grade of oral epithelial dysplasia (Group 1) was compared with tissue localization, cellular location, intensity of hTERT staining, nature of stain and percentage of cells stained [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase protein in (a) oral epithelial dysplasia (IHC stain, ×100) (b) oral squamous cell carcinoma (IHC stain, ×100), (c) normal oral mucosa (IHC stain, ×100), (d) dot-like nuclei, granular cytoplasm in oral epithelial dysplasia (IHC stain, ×400)

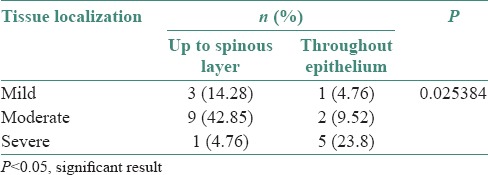

The distribution of tissue localization of immunostain and grading of oral epithelial dysplasia are shown in Table 2 (P = 0.025384).

Table 2.

Distribution of tissue localization of stain and grading in oral epithelial dysplasia

The distribution of cellular location of immunostain and grading or oral epithelial dysplasia are shown in Table 3 (P value 0.000928).

Table 3.

Distribution of cellular localization of stain and grading in oral epithelial dysplasia

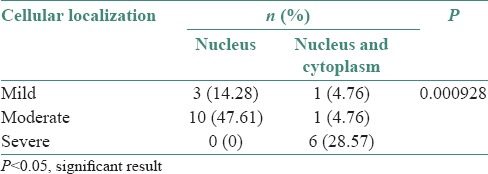

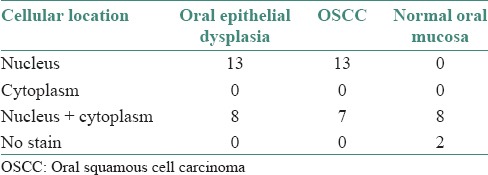

The distribution of cellular localization of immunostain in the study groups are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Distribution of cellular localization of stain in the study groups

The mean percentage of hTERT positive cells in Group 1 increased steadily through the grades of dysplasia and are as follows:

○ Mild oral epithelial dysplasia →64.68%

○ Moderate oral epithelial dysplasia →81.24%

○ Severe oral epithelial dysplasia →85.26%

• The mean percentage of cells in oral epithelial dysplasia was 77.06%.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

The histopathological grade of OSCC (Group 2) was compared with, cellular location, nature of stain, intensity of hTERT staining and percentage of cells stained [Figure 1].

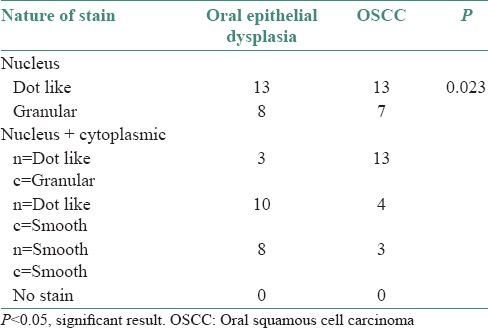

The distribution of nature of stain in oral epithelial dysplasia and OSCC are shown in Table 5 (P = 0.023).

Table 5.

Distribution of nature of stain in oral epithelial dysplasia and oral squamous cell carcinoma

-

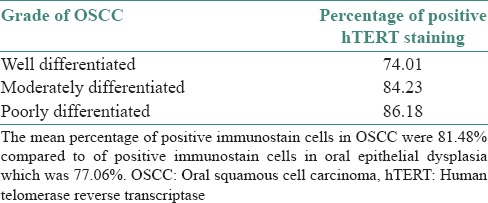

The mean percentage of cells expressing hTERT steadily increased through the grades of differentiation of OSCC

- ○ Well differentiated OSCC →74.01%

- ○ Moderately differentiated OSCC →84.23%

- ○ Poorly differentiated OSCC →86.18%

The mean percentage of cells in OSCC were 81.48% [Table 6].

Table 6.

Intensity of human telomerase reverse transcriptase staining in various grades of oral squamous cell carcinoma

DISCUSSION

hTERT is a nuclear protein generally repressed in normal cells and up-regulated in immortal cells, suggesting that hTERT is the primary determinant for the enzyme activity in normal and cancerous cells whereas increased hTERT expression is predominantly observed in cancerous cells.[5,19] The regulation of telomerase activity occurs at various levels, including transcription, mRNA splicing, maturation and modifications of hTR and hTERT, transport and sub-cellular localization of each component, assembly of active telomerase ribonucleoprotein and accessibility and function of the telomerase ribonucleoprotein on telomeres.[5]

Use of IHC is a useful, reliable method of localizing the hTERT protein in tissue sections.[12,15] Telomerase activity is conventionally studied using modified polymerase chain reaction, the telomeric repeat amplification protocol assay. This technique does not permit cellular localization of telomerase activity which is better demonstrated with techniques likes IHC/in situ hybridization. Cellular localization of the stain was defined as being either nuclear or cytoplasmic or both. hTERT immunostaining was localized diffusely in the nucleoplasm and more strongly in the nucleoli of cancer cells. It is important to detect cellular localization as it helps us identify the cells on the path of malignant transformation. In this study, immunohistochemical expression of hTERT protein was analyzed and compared among normal, oral epithelial dysplasia and OSCC samples.

In our study, ten cases of normal oral mucosa samples were examined, whereas Kumar et al.[10] reported four cases of normal oral mucosa and four cases of hyperplastic oral mucosa. While Abrahao et al.[11] reported five cases of oral epithelial hyperplasia without dysplasia.

In the present study, the mean percentages of hTERT positive cells in normal oral mucosa samples were 62.91%. These results show that normal oral epithelium expresses hTERT synthesized in cytoplasm and later translocated into nucleus. This was less as compared to 80 ± 14% reported by chen et al.[20]

Kumar et al.[10] reported that more than 50% of the cells showed hTERT expression in the basal and parabasal layers which are the normal proliferative progenitor compartment and contain stem cells which have hTERT or telomerase activity. Abrahao et al.[11] reported 100% (5/5) in oral epithelial hyperplasia without dysplasia.

Mutirangura et al.[8] reported telomerase expression in 43% (10/23) of leukoplakia; Kannan et al.[21] reported that 75% (27/36) of leukoplakia expressed telomerase activity and Liao et al.[22] showed that 54.5% (12/22) of leukoplakia samples had telomerase expression. Abrahao et al.[11] reported 100% (15/15) hTERT expression in potentially malignant disorders (leukoplakia and erythroplakia). Kumar et al.[10] also reported 100% (4/4) hTERT expression.

Chen et al.[20] reported OSCC labeling scores of 84 ± 35% and 91.33% in males and females respectively in their study. Abrahao et al.[11] reported 85.5% of hTERT positive cells in their study of well to poorly differentiated OSCCs. Kumar et al.[10] reported that 100% (10/10) cases of OSCC expressed hTERT. In this study, 61.90% (13/21) of oral epithelial dysplasia, 65% (13/20) of OSCC showed significant nuclear staining and some cases showed combined nuclear and cytoplasmic staining [Table 4]. The localization of hTERT expression in cytoplasm which represents phosphorylated and inactive forms of the protein, probably awaiting nuclear translocation has been previously reported in carcinomas of breast, cervix and larynx.[17,23,24]

In the present study, staining was visualized within the nucleus in 61.9% of oral epithelial dysplasia and 65% of OSCC cases predominantly in the dot like pattern. There was a statistically significant difference in the nature of nuclear stain in the study groups (P = 0.023), similar to the study reported by Luzar et al.[9] Yan et al.[18] demonstrated that hTERT immunostaining was localized diffusely in the nucleoplasm and more strongly in the nucleoli of cancer cells and proliferating normal cells. Tahara et al.[25] showed positive hTERT stain in colonic carcinoma cell nuclei and also in the epithelial cell nuclei of normal colonic crypts.

In the present study, the mean percentage of cells showing hTERT expression from normal oral mucosa to oral epithelial dysplasia to OSCC cases was 62.91% to 77.06% to 81.48% respectively. As well as this trend of increased expression were seen within groups of oral epithelial dysplasia and OSCC.[11,26,27]

The inter-observer agreement with the intensity of staining between oral epithelial dysplasia and OSCC were statistically significant.

The present study also showed steady increase in the expression of hTERT from normal oral mucosa to oral epithelial dysplasia to OSCC cases. When telomere becomes short reaching critical length,[5] telomerase is activated in premalignant and malignant cells. There is a steady increase in level of nuclear expression of hTERT in the oral epithelial dysplasia and OSCC cases than in normal oral mucosa. This indicates that an increased hTERT expression is to maintain chromosomal stability and to promote cell proliferation in oral epithelial dysplasia and OSCC lesions than in normal oral mucosa.

In the present study, stromal lymphocytes also showed strong and distinct hTERT expression similar to Kumar et al.[10]

This is a preliminary attempt at detecting human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) protein using IHC with a monoclonal antibody on paraffin embedded tissues samples representing multistage oral carcinogenesis. The intense expression of hTERT in potentially malignant lesions and OSCC suggests that telomerase activity is involved in the development of dysplastic epithelium leading to multistage oral carcinogenesis. The biological significance of hTERT expression in differentiation of committed and proliferating cells needs further studies to elucidate if hTERT may be a useful diagnostic or prognostic marker in oral potential malignant disorders and cancer.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

I avail this opportunity to sincerely thank Dr. Radhika M. Bavale, Professor and Head, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences, Bangalore; Dr. Mandana Donoughe, Professor and Head, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere; Dr. B. R. Mujib Ahmed, Professor and Head, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Bapuji Dental College and Hospital, Davangere for their generosity and support in completion of this study.

I also acknowledge the help rendered by Mrs. Dorothy Anita and Ms. Priyadarshini, our lab technicians.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W B Saunders; 2002. Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology; pp. 338–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feller L, Lemmer J. Oral Leukoplakia as It Relates to HPV Infection: A Review. Int J Dent 2012. 2012:540561. doi: 10.1155/2012/540561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddad RI, Shin DM. Recent advances in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1143–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenspan D, Jordan RC. The white lesion that kills – Aneuploid dysplastic oral leukoplakia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1382–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cong YS, Wright WE, Shay JW. Human telomerase and its regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:407–25. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.407-425.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chimenos-Küstner E, Font-Costa I, López-López J. Oral cancer risk and molecular markers. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2004;9:381–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao L, El-Naggar AK, Fan YH, Lee JS, Lippman SM, Kayser S, et al. Telomerase activity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and adjacent tissues. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5600–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mutirangura A, Supiyaphun P, Trirekapan S, Sriuranpong V, Sakuntabhai A, Yenrudi S, et al. Telomerase activity in oral leukoplakia and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3530–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luzar B, Poljak M, Gale N. Telomerase catalytic subunit in laryngeal carcinogenesis – An immunohistochemical study. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:406–11. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar SK, Zain RB, Ismail SM, Cheong SC. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression in oral carcinogenesis – A preliminary report. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2005;24:639–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrahao AC, Bonelli BV, Nunes FD, Dias EP, Cabral MG. Immunohistochemical expression of p53, p16 and hTERT in oral squamous cell carcinoma and potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res. 2011;25:34–41. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242011000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palani J, Lakshminarayanan V, Kannan R. Immunohistochemical detection of human telomerase reverse transcriptase in oral cancer and pre-cancer. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:362. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.84281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downey MG, Going JJ, Stuart RC, Keith WN. Expression of telomerase RNA in oesophageal and oral cancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:577–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.301001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang LY, Lin SC, Chang CS, Wong YK, Hu YC, Chang KW. Telomerase activity and in situ telomerase RNA expression in oral carcinogenesis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:389–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiyama E, Hiyama K, Yokoyama T, Shay JW. Immunohistochemical detection of telomerase (hTERT) protein in human cancer tissues and a subset of cells in normal tissues. Neoplasia. 2001;3:17–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anneroth G, Hansen LS, Silverman S., Jr Malignancy grading in oral squamous cell carcinoma. I. Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and floor of mouth: Histologic grading in the clinical evaluation. J Oral Pathol. 1986;15:162–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1986.tb00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luzar B, Poljak M, Marin IJ, Gale N. Telomerase reactivation is an early event in laryngeal carcinogenesis. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:841–8. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000086488.36623.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan P, Benhattar J, Seelentag W, Stehle JC, Bosman FT. Immunohistochemical localization of hTERT protein in human tissues. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;121:391–7. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0645-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryce LA, Morrison N, Hoare SF, Muir S, Keith WN. Mapping of the gene for the human telomerase reverse transcriptase, hTERT, to chromosome 5p15.33 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Neoplasia. 2000;2:197–201. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen HH, Yu CH, Wang JT, Liu BY, Wang YP, Sun A, et al. Expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) protein is significantly associated with the progression, recurrence and prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Taiwan. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannan S, Tahara H, Yokozaki H, Mathew B, Nalinakumari KR, Nair MK, et al. Telomerase activity in premalignant and malignant lesions of human oral mucosa. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:413–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao J, Mitsuyasu T, Yamane K, Ohishi M. Telomerase activity in oral and maxillofacial tumors. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:347–52. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frost M, Bobak JB, Gianani R, Kim N, Weinrich S, Spalding DC, et al. Localization of telomerase hTERT protein and hTR in benign mucosa, dysplasia, and squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:726–34. doi: 10.1309/XWFE-ARMN-HG2D-AJYV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyo S, Takakura M, Ishikawa H, Sasagawa T, Satake S, Tateno M, et al. Application of telomerase assay for the screening of cervical lesions. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1863–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tahara H, Yasui W, Tahara E, Fujimoto J, Ito K, Tamai K, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of human telomerase catalytic component, hTERT, in human colorectal tumor and non-tumor tissue sections. Oncogene. 1999;18:1651–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HR, Christensen R, Park NH, Sapp P, Kang MK, Park NH. Elevated expression of hTERT is associated with dysplastic cell transformation during human oral carcinogenesis in situ. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3079–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yajima Y, Noma H, Furuya Y, Nomura T, Yamauchi T, Kasahara K, et al. Quantification of telomerase activity of regions unstained with iodine solution that surround oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:314–20. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]