Abstract

The increased use of PET amyloid imaging in clinical research has sparked numerous concerns about whether and how to return such research test results to study participants. Chief among these is the question of how best to disclose amyloid imaging research results to individuals who have cognitive symptoms that could impede comprehension of the information conveyed. We systematically developed and evaluated informational materials for use in pre-test counseling and post-test disclosures of amyloid imaging research results in mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Using simulated sessions, persons with MCI and their family care partners (N=10 dyads) received fictitious but realistic information regarding brain amyloid status, followed by an explanation of how results impact Alzheimer’s disease risk. Satisfaction surveys, comprehension assessments, and focus group data were analyzed to evaluate the materials developed. The majority of persons with MCI and their care partners comprehended and were highly satisfied with the information presented. Focus group data reinforced findings of high satisfaction and included 6 recommendations for practice: 1) offer pre-test counseling, 2) use clear graphics, 3) review participants’ own brain images during disclosures, 4) offer take-home materials, 5) call participants post-disclosure to address emerging questions, and 6) communicate seamlessly with primary care providers. Further analysis of focus group data revealed that participants understood the limitations of amyloid imaging, but nevertheless viewed the prospect of learning one’s amyloid status as valuable and empowering.

INTRODUCTION

Amyloid imaging techniques including positron emission tomography (PET) scanning with F 18 labeled radioligands and Pittsburgh Compound B have rapidly become a standard component of clinical research protocols involving participants with and at risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). With the increasing use of these compounds in research settings have come a set of questions concerning whether and how to disclose such results to individuals with clinical presentations ranging from cognitively healthy to dementia [1]. Focusing on the use of PET amyloid imaging in research participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), our group recently outlined the circumstances under which investigators may bear an ethical obligation to offer such test results to study participants [2]. We examined the ethical, regulatory and clinical implications of disclosing amyloid imaging research results to persons with MCI and concluded that validated PET amyloid research scan results should, with limited exceptions (e.g., active suicidal ideation), be made available to participants who make an informed decision to receive them.

Acceptance of the possibility that research amyloid PET results may be disclosed under certain circumstances requires investigators to be equipped with a carefully managed approach to returning such research results, even though disclosure is not currently considered standard of practice in academic settings. At minimum, a prudent approach to disclosing research PET amyloid imaging results to persons with MCI would require that the information be conveyed in a manner that is comprehensible to participants and reflects the most current evidence on the relationship between brain amyloid status and risk of progression to AD. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development, pilot testing, and refinement of materials for use when counseling research participants prior to amyloid imaging (pre-test counseling) and when disclosing amyloid imaging research results in the context of MCI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protocol Development

The process of protocol development began with an examination of consensus body recommendations for genetic counseling in Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s disease [3, 4]. The rationale for examining guidelines for genetic counseling was twofold. First, many of the issues associated with testing for genetically based risk for neurodegenerative disease, like the potential for psychological distress, also apply to testing for non-genetic biomarkers of AD, especially amyloid imaging. Second, consensus body recommendations for genetic testing in AD are informed by decades of empirical research on the most effective approaches to pre-test counseling and results disclosure, and reflect a process of rigorous discussion among a diverse group of stakeholders.

Upon review of these recommendations we identified elements of genetic counseling (e.g., information about testing, impact of testing, reflection) that would potentially apply to counseling sessions focused on amyloid imaging. We created a table summarizing our findings and highlighting areas of concern, which we circulated among a panel of experts from the fields of neuroimaging, bioethics, risk communication, neuropsychology, geriatric psychiatry and regulatory affairs. The 9-member multidisciplinary panel engaged in an iterative discussion of the applicability of each element recommended for use in genetic counseling to the context amyloid imaging, and worked to identify additional elements that may be relevant to amyloid imaging but are not present in existing protocols for genetic counseling in AD. Content regarding reproductive decision making, for example, is standard in genetic counseling for AD, but was not deemed by the panel to represent key information to be conveyed during pre-test counseling for PET amyloid imaging. In contrast, pre-test counseling for amyloid imaging in symptomatic populations such as MCI requires a clear discussion of limitations of the testing, as is similarly necessary in genetic counseling. Specifically, there is a need for a clear explanation of the test’s specificity for AD as opposed to non-AD forms of dementia, which could represent alternative underlying causes of MCI symptoms for which amyloid imaging would not be informative. This process of analysis continued until a final set of core elements for amyloid imaging counseling was agreed upon by panel members.

Once the core elements for amyloid imaging counseling were identified, we created text to provide a basic description of PET amyloid imaging, potential results of amyloid imaging (positive, negative, and inconclusive), interpretation of such results in the context of MCI, and general recommendations for participants receiving each type of result. A set of visual aids to accompany this text was developed based on previous work by the Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer’s Disease (REVEAL) team [5]. The same 9-member expert panel engaged in a second round of iterative review to reach consensus on the relevance and clarity of the text and visual aids that were developed or adapted.

Pilot testing

Although materials were developed for use in both pre- and post-test counseling sessions, pilot testing focused on the text and visual aids that would be used during amyloid imaging results disclosure. To assess the clarity and comprehensibility of the text and visual aids, 10 MCI care dyads (patient + family member) were recruited from the Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC) at the University of Pittsburgh. All patient participants met ADRC enrollment criteria [6]. Those eligible for this pilot testing also had to: 1) carry a current ADRC consensus diagnosis of MCI (isolated impairment in memory; isolated deficit in non-memory domain; or, mild deficits in multiple cognitive domains) [7]; and 2) provide written informed consent to participate. The exclusion criteria were: 1) familial Alzheimer’s disease genetic mutation carriers (this group already has biomarker-derived knowledge of their dementia risk); and 2) previous participation in an amyloid imaging research study (to avoid any confusion over whether the hypothetical results are actually real). Family member participants had to: 1) be at least 18 years of age; 2) be English speaking; and 3) provide written informed consent to participate.

After providing informed consent, dyads were separated for the administration of a health literacy measure, the Newest Vital Sign [8]. Dyads then came together to undergo a simulated amyloid imaging results disclosure session using the test and visual aids developed through the above-described process. Simulation sessions began by instructing participants to imagine that the dyad member with MCI had recently undergone a new type of brain scan designed to detect the presence of AD brain pathology, and to imagine that they have come in to learn of the scan results. Participants were instructed to ask questions during the simulation and to make every attempt to conduct themselves as though the information being conveyed was real. Four of the dyads were randomized to receive hypothetically positive amyloid imaging scan results, 4 were randomized to hypothetically negative results, and 2 received hypothetically inconclusive results.

Following each simulation, patients with MCI and their family members were interviewed separately to assess comprehension of the hypothetical information conveyed and satisfaction with the interaction. Comprehension assessments were adapted from those used in the REVEAL studies and consisted of two open ended questions: 1) “Please tell me the mock results of your PET scan in your own words,” and 2) “Please explain what these results mean in terms of your (or your loved one’s) chances of developing Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia.” Responses to these questions were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Blinded to the type of respondent (patient with MCI vs. family member), an interdisciplinary team of 4 faculty and Master’s level staff from nursing, public health, neuropsychology, and bioethics, rated responses as demonstrating adequate or inadequate evidence of comprehension. Ratings were conducted using a consensus meeting format to reach agreement following a scoring rubric that the team developed as part of this process. According to the scoring rubric developed by this team, features of adequate responses included: paraphrasing results and/or the explanation of their implications for AD risk; applying an appropriate value or direction (e.g., “high”) to AD risk or acknowledging the uncertainty of the information’s implications for one’s personal trajectory, often in combination with naming one’s result. A rating of inadequate evidence of comprehension was applied when a participant expressed frank confusion or offered a vague response to the comprehension questions.

Finally, with participants’ explicit consent, basic sociodemographic information and other sample characteristics were abstracted from each participant’s most recent ADRC visit record.

Protocol refinement

After completion of the pilot testing, we conducted a focus group with a subset of pilot study participants to engage these individuals in a broader discussion of the process of pre- and post- scan education and counseling. The focus group included four persons with MCI and four family members of persons with MCI, and included representation from individuals with a range of responses to the satisfaction and comprehension questions posed during the pilot testing phase of the study. Focus group attendees were not required to participate as dyads, although 2 families did so.

The focus group interview guide was designed and implemented following standard guidelines, including the use of semi-structured questions with cues and prompts to facilitate a rich exchange of viewpoints [10,11]. Specifically, the focus group guide consisted of a brief recap of amyloid in MCI and 14 open-ended questions and 9 follow up probes designed to augment the satisfaction data collected in the pilot study and to determine what, if any, additional information and support might be beneficial to those contemplating amyloid imaging. The audiorecording of the focus group was transcribed verbatim, yielding 32 single spaced pages of discussion, the content of which was analyzed using qualitative description [12]. Consistent with this methodological approach, three investigators performed line-by-line coding of the transcript, iteratively generating and refining a set of descriptive categories to group codes based on their similarities. After individually coding the data, this team convened to review and compare categories, and to identify emerging themes within the data.

RESULTS

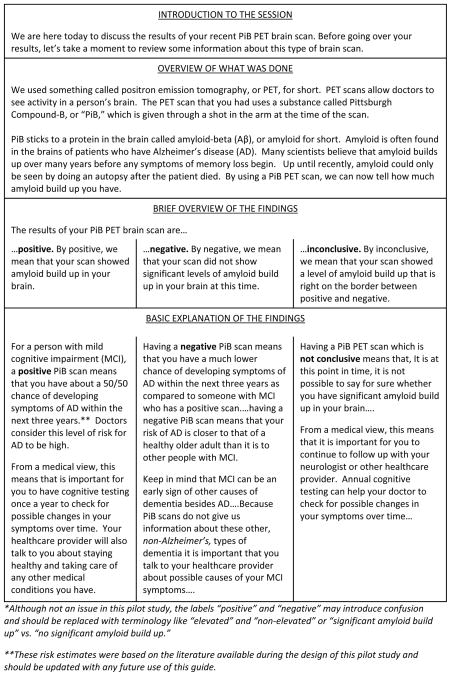

Disclosure scripts for positive, negative, and inconclusive results, with accompanying visual aids, were developed. Each script was sequenced to review the purpose of amyloid imaging, disclose a hypothetical result, and interpret that result in terms of AD risk and recommendations for clinical follow up (see Figure 1). Scripts ranged from 245 to 300 words with Flesch-Kincaid reading levels of 8th to 9th grade [9].

Figure 1.

Excerpts from Mock Scripts, Positive, Negative & Inconclusive*

Pilot test findings

Characteristics of participants in the results disclosure simulation are described in Table 1. Of note, most (n = 7) of the family member participants, but only half (n = 5) of the patients with MCI had NVS scores indicative of adequate health literacy. Mean ratings of satisfaction with the simulated results disclosure session are presented in Table 2. All 20 participants agreed or strongly agreed that information in the session was “clearly presented.” Nineteen of 20 (95%) agreed or strongly agreed with statements indicating that the session was “easy to follow,” and “just about right” in length. Agreement with the statement “After the….session, I still had questions about my (or my loved one’s) mock results” varied widely among both patient and family member participants.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Variable | Patient (n=10) | Family Member (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age in yrs (range) | 78.6 (69–92) | 63.2 (43–77) |

| Education | ||

| < H.S. | 2 | 0 |

| H.S./GED | 2 | 3 |

| Technical school or College | 4 | 4 |

| Graduate school | 2 | 3 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 5 | 7 |

| Male | 5 | 3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black/African American | 1 | 1 |

| White/Caucasian | 9 | 9 |

| Relationship | ||

| Spouse/partner | 8 | |

| Adult child | 2 | |

| MCI subtype | ||

| Amnestic | 9 | |

| Non-amnestic | 1 | |

| Health Literacy Score* | ||

| 0–1: indicates high likelihood of limited literacy | 3 | 0 |

| 2–3: indicates possibility of limited literacy | 2 | 3 |

| 4–6: almost always indicates adequate literacy | 5 | 7 |

using Newest Vital Sign

Table 2.

Satisfaction Results

| Satisfaction Question | Mean Score* (Range) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Patient | Family Member | |

| The mock PET scan results session was easy to follow. | 1.9 (1–4) | 1.3 (1–2) |

| The mock PET scan results session was too long. | 4.2 (3–5) | 4.1 (1–5) |

| The mock PET scan results session included just about the right level of detail. | 2.1 (2–3) | 1.8 (1–3) |

| The information provided in the mock PET scan results session was clearly presented. | 1.7 (1–2) | 1.4 (1–2) |

| After the PET scan results session, I still had questions about my (or my loved one's) mock results. | 3.4 (2–5) | 3.2 (1–5) |

| The visual materials, like graphs, used in the mock PET scan results session were clear. | 2.2 (1–4) | 1.7 (1–3) |

| The length of the mock PET scan results session was just about right. | 1.8 (1–2) | 2.0 (1–4) |

| The mock PET scan results session included too much detail | 4.4 (4–5) | 4.0 (2–5) |

1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neutral, 4 = disagree, 5 = strongly disagree

Based on the above-described scoring rubric for assessing comprehension of the information disclosed, 16 participants displayed adequate comprehension of their, or their loved one’s, hypothetical PET amyloid imaging results. Two patients with MCI and two family members provided responses that did not meet the rubric’s criteria for adequate comprehension. In each case that was rated as “inadequate,” the other member of the dyad did display adequate comprehension, underscoring the need to have at least two individuals present during results disclosure. Stated another way, there were no instances in which both members of a given dyad failed to meet our criteria for adequate comprehension. Scrutiny of the participant profiles of those displaying inadequate comprehension did not any reveal clear patterns with respect to characteristics of the participants (e.g., health literacy level or years of education) or the type of result presented (positive vs. negative).

Focus group findings

Upon qualitative analysis of the focus group data, the theme “satisfaction with the disclosure process,” emerged quickly during the analysis, serving to validate the findings from our initial post-simulation satisfaction surveys, with both patient and care partner participants consistently expressing the view that the information presented during the simulated disclosure sessions was clear and comprehensible. In addition to this finding, two more major themes emerged during data analysis; the first was “recommendations for best practice” and the second was “knowledge is power.”

Within the first theme were six specific suggestions for best practice: 1) offer pre-test counseling, 2) use clear graphics, 3) review patients’ own brain images during disclosure, 4) offer take-home materials describing follow-up options, 5) call patients post-disclosure to address emerging questions, and 6) communicate seamlessly with primary care providers. Exemplar quotes for each of these recommendations is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Theme: Suggestions for Best Practice

| Suggestion | Supportive Participant Quotes |

|---|---|

| Offer pre-test counseling | “what I would want to know ahead of time is what to anticipate, what are the risks, what are the benefits” |

| Use clear graphics | “..something like this you really have to [be], to use a government term, user-friendly. And you have to have it [the graphics] so that even a medium level can understand and if you get too technical then those people can’t comprehend” |

| Review participants’ own scan images during disclosure | In response to question about whether images of a normal vs. AD brain were helpful, “We haven’t seen what our own brains look like, so we can’t really compare it.“ “When its going on in the brain, we can’t see it, so we, it’s more of an abstract concept…When you see a picture, when you see that kind of thing, for me it makes it less abstract.” |

| Offer take home materials with follow up options | “I like the idea that at the end of our meeting, you have already prepared a package of these are your options…this is the information and you give me that as I am leaving. Don’t give it to me at the appointment, because I am going to rifle through it and try to follow along, but you give that to me at the end, and then I am armed with all the information that we went over in that meeting and I have it and then I am able to do with it what I need to, if I have a follow up call I have that information. “ |

| Call patients post-disclosure to address emerging questions | “…there on the spot, you don’t know what to ask. Because it’s depending upon what it is that they have told you, you don’t know what to anticipate. So it’s almost as if you need a period to digest everything and then your better able to formulate whatever the question may be” “A phone is a great communicator. And the person can call and say do you have any questions? How are things going for you? “ |

| Communicate seamlessly with primary care providers | “Okay, so you say go see your primary care [provider], so is there communication between this group and this group and this group? So that everybody is sort of on the same page.” |

The second theme, “knowledge is power,” reflects participants’ widely shared view that there was inherent value in learning one’s brain amyloid status, irrespective of the type of result that one might receive or whether that result would lead to a change in the treatment approach. Participants expressed this view with statements such as “Knowledge is strength. It helps you to do the best for the people you love and yourself” made by the husband of a woman with MCI. Similarly, a widowed woman with MCI described how she would use the information as a basis for future medical decision making “[using results] to write down what I would want to have happen [in the future]” and adding, “the unknown is sometimes the hardest.” While the majority of focus group participants expressed support for this perspective, the following quote from the wife of a participant with MCI shows the potential for uncertainty regarding the value of advanced diagnostic testing for AD pathology, “At least [with breast cancer testing] you can, they do a double mastectomy and reduce your risks, but so far with Alzheimer’s they have no idea what’s causing it, well very little idea. And there’s nothing they can do. So I’m not sure, I’ve never quite figured out if it’s worth it, to know. To know what’s happening because you can’t do anything with it.”

The notion of information’s inherent value, as distinct from and despite the lack of pragmatic use of the information, is exemplified by the following quote from a woman with MCI who participated in the study with her husband as her care partner, “[some people think] but nothing can be done about it yet [so] why do we want to burden ourselves knowing this is the direction we are going in. And our attitude is very different. We want to know as much as we can.” In another case, the value of an amyloid scan, if positive, was considered would be to serve as validation of the symptoms that one spousal care partner and his wife were witnessing: “…[if other family members had this information] they could no longer stick their head in the sand.” However, it was not clear whether a negative scan would be viewed as equally important.

DISCUSSION

We used a systematic approach to develop, evaluate, and refine materials to guide pre-test counseling and results disclosure for PET amyloid imaging. Findings from the preliminary testing of these materials among persons with MCI and their family members suggest that this basic information about PET amyloid imaging is generally perceived as satisfactory to, and comprehended by, such individuals. Given the divergent range of ratings that participants provided to our query about the their satisfaction with the level of detail provided in the sessions, there is a clear need for those disclosing such results to be flexible and responsive to patient and family member preferences for information.

Findings from the qualitative analysis of focus group data indicate that patients with MCI and their care partners may find value in learning the results of amyloid imaging research tests irrespective of whether results are clinically actionable. Such preferences demonstrate that patients and family members may be appraising test results from a personal utility viewpoint, whereas the medical community (and payers of health care services) most often judge imaging assessments from a clinical utility perspective. Should amyloid imaging become more widely available either in research or clinical contexts, this potential tension between personal and clinical utility may influence decision making regarding use of this emerging technology. While our study focused on the return of amyloid imaging results in the research rather than clinical setting, this finding underscores the potential value—and diverse nature—of such disclosure.

With regard to the clinical setting, the recently published set of appropriate use criteria (AUC) for amyloid PET categorize individuals with persistent or progressive unexplained MCI as appropriate candidates for PET amyloid imaging [13]. Several of the recommendations by participants in the current study could be readily implemented when applying AUC in practice, whereas other suggestions from our participants may pose challenges to those striving to conduct disclosure sessions in a clear and comprehensible way. For example, the recommendations to use clear graphics and offer take home materials are both practical strategies that have broad support in the patient education literature and been shown to improve comprehension (particularly among lower numeracy individuals) and reduce biases in medical decision-making [14–16]. In our team’s subsequent study of disclosing actual amyloid imaging results, we replaced bar graphs with pictographs to depict the risk of conversion to AD based on brain amyloid status. The pictographs for this information show 100 outlines of individual people, similar to stick figures, wherein shaded figures represent the proportion of MCI cases who are likely to develop AD over a 3-year period based on brain amyloid status. Take home materials include a one-page summary of the results and their implications. On the other hand, the suggestion to review one’s own brain image during the disclosure session may be less feasible to implement and may not confer as much value as participants might expect. Note that this recommendation emerged following a simulated disclosure in which research participants viewed multi-color renderings of representative positive and negative scans, whereas in practice, an individual’s own raw, grey-scaled image may be perceived as less useful.

It should also be noted that our sample was small and comprised of research friendly individuals from an ADRC who reported having relatively high levels of education. We nevertheless observed instances of questionable comprehension of the information conveyed through the simulated results disclosure sessions. Those instances led our team to discuss additional areas where our protocol could be improved. While not an issue in the current study, there was consensus within our team that the terms “positive” and “negative” may cause confusion because in most contexts positive information is considered to be a good thing. Alternative phrasing may include terms such as “elevated” or “non-elevated”, or text describing the presence or absence of significant levels of amyloid “build up.”

More generally, we recommend that protocols for disclosing amyloid imaging research results include the following safeguards to maximize comprehension of the information conveyed: 1) pre-disclosure counseling, 2) post-disclosure assessments of results comprehension, and 3) encouragement of participants to involve family members or other persons from their support networks in as many aspects of the process as possible. Although not examined in the current study of simulated amyloid imaging disclosures, in practice, such safeguards might also help to minimize the emotional distress associated with receiving information about one’s brain amyloid status.

Finally, it must be underscored that the values we used to estimate the risk of progression to AD based on amyloid status were derived from the literature available at the time of the study’s design. Given the rapidly accumulating evidence in this area of science, future protocols should incorporate updated risk estimates, preferably based on large-scale prospective longitudinal studies of progression from MCI to AD. In instances where new risk estimates substantially differ from those provided to research participants based on early studies, researchers may need to recontact participants and offer updated information to those for whom revised risk information could be relevant.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND SOURCES OF SUPPORT

The authors wish to thank Drs. Jason Karlawish, Keith Johnson, and Julie Price for their early contributions to this project and for their service on the expert panel described in this manuscript. This study was supported by a seed monies grant from the Aging Institute of UPMC Senior Services and the University of Pittsburgh (PI: Lingler) and by NIH/NIA, P50 AG05133 (PI: Lopez).

Footnotes

Portions of this research were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in July 2012, Vancouver CA, July 2013, Boston MA.

Contributor Information

Jennifer H. Lingler, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Department of Health and Community Systems.

Meryl A. Butters, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry.

Amanda L. Gentry, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Department of Health and Community Systems.

Lu Hu, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Department of Health and Community Systems.

Amanda E. Hunsaker, University of Pittsburgh School of Social Work.

William E. Klunk, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry.

Meghan K. Mattos, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Department of Health and Community Systems.

Lisa A. Parker, University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, Department of Human Genetics.

J. Scott Roberts, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Department of Health Behavior & Health Education.

Richard Schulz, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry Director, University Center for Social and Urban Research.

References

- 1.Harkins K, Sankar P, Sperling R, Grill JD, Green RC, Johnson KA, Healy M, Karlawish J. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2015;7:26. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lingler J, Klunk WE. Disclosure of amyloid imaging results to research participants: Has the time come? Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:741–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman JS, Hahn SE, Catania JW, Larusse-Eckert S, Butson MB, Rumbaugh M, Strecker MN, Roberts JS, Burke W, Mayeux R, Bird T. Genetic counseling and testing for Alzheimer disease: joint practice guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Gen Med. 2011;13:597–605. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821d69b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Huntington Association (IHA) and the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) Research Group on Huntington’s Chorea. Guidelines for the molecular genetics predictive test in Huntington’s disease. Neurology. 1994;44:1533–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts JS, Christensen KD, Green RC. Using Alzheimer’s disease as a model for genetic risk disclosure: Implications for person genomics. Clin Genet. 2011;80:407–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Klunk WE, Saxton J, Hamilton R, Kaufer DI, … DeKosky ST. Research evaluation and diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease over the last 2 decades: I. Neurology. 2000;55:1854–1862. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.12.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, Becker JT, Fitzpatrick A, Dulberg C, … Kuller LH. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study: Part 1. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60:1385–1389. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osborn CY, Weiss BD, Davis TC, Skripkauskas S, Rodrgue C, Bass PF, Wolf MS. Measuring adult literacy in health care: Performance of the Newest Vital Sign. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:S36–S46. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Jr, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Research Branch Report. Millington, TN: Naval Technical Training, U.S. Naval Air Station; Memphis, TN; 1975. Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy-enlisted personnel; pp. 8–75. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanfield RB. The art of focused conversation: 100 ways to access group wisdom in the workplace. 2. Toronto, ON: The Canadian Institute of Cultural Affairs; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, Donohoe KJ, Foster N, Herscovitvh P…Thies WH. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: A report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013;9:e1–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hout PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, Loscalzo MJ. The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;61:173–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawley ST, Zikmund-Fisher B, Ubel P, Jancovic A, Lucas T, Fagerlin The impact of the format of graphical presentation on health-related knowledge and treatment choices. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;73:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Retamero R, Galesic M. Who profits from visual aids: overcoming challenges in people’s understanding of risks. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]