Abstract

CD48, a member of the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule family, participates in adhesion and activation of immune cells. Although constitutively expressed on most hematopoietic cells, CD48 is upregulated on subsets of activated cells. CD48 can have activating roles on T cells, antigen presenting cells and granulocytes, by binding to CD2 or bacterial FimH, and through cell intrinsic effects. Interactions between CD48 and its high affinity ligand CD244 are more complex, with both stimulatory and inhibitory outcomes. CD244:CD48 interactions regulate target cell lysis by NK cells and CTLs, which are important for viral clearance and regulation of effector/memory T cell generation and survival. Here we review roles of CD48 in infection, tolerance, autoimmunity, and allergy, as well as the tools used to investigate this receptor. We discuss stimulatory and regulatory roles for CD48, its potential as a therapeutic target in human disease, and current challenges to investigation of this immunoregulatory receptor.

1. Introduction

Genetic and functional studies have identified members of the signaling lymphocyte activation marker (SLAM) family as important molecules in immune cell function, with roles in tolerance, autoimmunity, and allergy [1, 2]. Encoded on chromosome 1 in mice and 1q23 in humans [3, 4], the SLAM family includes CD48 (SLAMF2, BLAST-1) [5], a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linked protein constitutively expressed on the surface of nearly all hematopoietic cells. Initially discovered as a molecule upregulated on blasting B cells during Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection [6], CD48 contributes to several immunological processes through its interactions with ligands CD2 and CD244. CD48 is involved in cell adhesion and costimulation [7-10], regulation of target cell lysis by cytolytic cells [11-18], as well as detection of microbes through its interaction with the bacterial component FimH [19, 20]. In this review we first provide a brief overview of the SLAM family and then focus on our current understanding of the immunoregulatory functions of CD48.

2. Overview of the SLAM family

The SLAM family (SLAMF) includes nine cell surface receptors, which participate in diverse aspects of immune function including costimulation, cytokine production, and cytotoxicity [1, 2]. The family includes CD150 (SLAM, SLAMF1), CD48 (SLAMF2, BLAST-1), CD229 (SLAMF3, Ly9), CD244 (SLAMF4, 2B4), CD84 (SLAMF5), CD352 (SLAMF6, Ly108, NTB-A in humans), CD319 (SLAMF7, CRACC), CD353 (SLAMF8, BLAME), and CD84H (SLAMF9, SF2001). Most SLAM family proteins engage in homotypic interactions [21-29], although SLAMF8 and SLAMF9 do not have defined ligands [30-33], and CD48 and CD244 form a receptor-ligand pair. For the homophilic SLAMF molecules, ligand engagement results in signaling through one or more cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motifs (ITSM), mediated by the intracellular adaptors SLAM-associated protein (SAP) and/or EWS-Fli1-activated transcript-2 (EAT-2) [34-38]. Less is known about signaling intermediates for SLAMF8 and SLAMF9, which do not contain tyrosine motifs in their intracellular domains [30-33]. CD48 is GPI-linked and associates with signaling molecules in cholesterol-rich lipid rafts [3, 39].

3. The SLAM family locus on mouse chromosome 1 and association with spontaneous autoimmunity

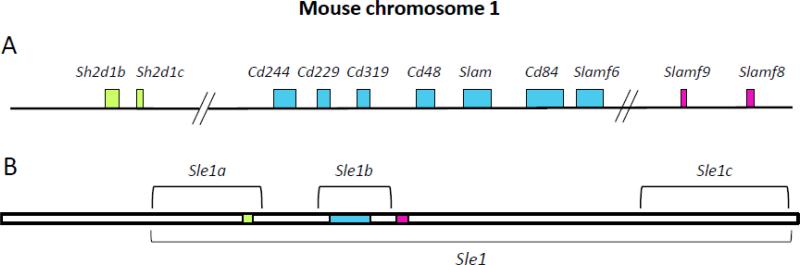

In addition to many functional studies of the SLAM family proteins, genetic studies have associated the SLAM family with regulation of tolerance and autoimmunity. Investigation of the genetic basis of lupus-susceptibility in the NZM2410 mouse strain resulted in the identification of several regions that contributed to this phenotype—including a region on chromosome 1 that contains the SLAM family genes (Fig. 1) [40, 41]. During crosses between healthy B6 and lupus-prone NZM2410 mice, offspring that inherited the Sle1 allele on chromosome 1 from NZM2410 mice were found to develop glomerulonephritis and anti-nuclear antibodies [41, 42]. Extensive characterization of the Sle1 region revealed multiple loci that independently contribute to lupus-like disease on the B6 background [42], including the Sle1b subregion that has the strongest link to humoral autoimmunity and contains the SLAM family genes [42, 43].

Figure 1. The SLAM locus.

CD48 is located on chromosome 1 in mice, and chromosome 1q23 in humans. In mice, the SLAM locus overlaps with the lupus-susceptibility region Sle1b. The larger Sle1 lupus susceptibility locus includes additional genes including Sh2d1b (EAT-2), Sh2d1c (ERT), Slamf8 and Slamf9. A. Schematic of SLAM family genes, and the SAP adaptors EAT-2/EAT-2B, on mouse chromosome 1. B. Schematic of the Sle1 locus, highlighting the locations of the SLAM family genes within this region.

Further characterization of the SLAM family region identified two haplotypes among inbred mouse strains: one found in C57BL/6 (B6) strains (haplotype 1), and a second in NZW, Balb/c, 129 and NOD strains (haplotype 2). These haplotypes differ slightly in their expression levels of SLAM family genes, but also contain polymorphisms in multiple SLAM family genes including CD244 and CD229 [43]. SLAM haplotype 2 alleles cause autoimmunity when expressed in the B6 strain, but not in several other mouse strains, including 129/SvJ and NZW, suggesting that epistatic interactions between haplotype 2 SLAM family genes and regions of the B6 genome lead to autoimmunity [43, 44]. The precise mechanisms are still under investigation, and likely involve multiple SLAM family members and other proteins they interact with, such as signaling molecules and adaptors.

Recent studies indicate that differential expression of Ly108 (SLAMF6) isoforms contributes to this lupus-like phenotype. Kumar et al. showed that expression of the Ly108.1 isoform results in decreased BCR sensitivity and reduced cell death, compared to expression of the Ly108.2 isoform [45], suggesting that Ly108.1 may contribute to lupus susceptibility. A third isoform, Ly108-H1, is uniquely expressed in B6 mice but not in several lupus-prone strains, and limits autoimmunity when expressed as a transgene in a lupus-prone strain [46]. These results collectively point to prominent roles for Ly108 in precipitating or protecting from lupus-like disease associated with the Sle1b region, and indicate an important role for this SLAM family member in regulating autoimmunity.

Additionally, these studies have important implications for interpreting studies with some of the knockout mice generated to study SLAM family molecules. Many of the SLAMF-deficient strains were made by gene targeting in 129-derived embryonic stem (ES) cells, and then backcrossing on to the desired strain (e.g., B6 or Balb/c). For those strains backcrossed to B6, the resulting mice are deficient for the molecule of interest and also carry the 129-derived flanking genes associated with the lupus-prone phenotype. For example, CD150−/− and CD48−/− mice were generated with 129-derived ES cells. When backcrossed onto the B6 background, both strains develop spontaneous lupus-like disease with age. In contrast, when backcrossed on to the Balb/c background, these strains do not develop a lupus-like phenotype [47]. These multiple genetic differences should be kept in mind when evaluating data from studies using [B6.129] SLAMF-deficient strains.

4. CD48 structure and expression

CD48 is in the CD2 subfamily of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily, and shares many structural features with other Ig family members. The CD48 gene consists of 4 exons, including an Ig variable-like (IgV) domain and an Ig constant-like (Ig-C2) domain, with cysteine residues that allow a disulfide bond in the latter [3]. In humans, CD48 is alternatively spliced to generate two isoforms that differ in the 3’ UTR and coding region; isoform 1 is shorter than isoform 2 and these isoforms possess unique C termini. It is not yet known whether there are functional differences between these two isoforms. In mice, only one isoform has been described.

In lab strains of mice, CD48 is not significantly polymorphic; there is only one polymorphism that results in a single amino acid difference in the IgV-like domain in B6 compared to other lab strains and that is not predicted to affect binding of CD48 to CD2 [48]. In contrast, numerous polymorphisms exist in the Ig domains of CD48 in wild mouse populations [49]. At least two genomic variants of CD48 have been identified in humans [50], and genome-wide association studies have linked polymorphisms in CD48 to susceptibility to multiple sclerosis (MS) [51]. However, it is not yet known how these polymorphisms influence CD48 expression or function.

CD48 exists in both a membrane-bound and soluble form. CD48 is anchored to the cell membrane by a GPI linkage, which allows it to associate with cholesterol-rich lipid rafts and associated signaling molecules. CD48 also has been detected in a soluble form in human serum and plasma [52]. It is not known how the soluble form of CD48 is generated, but GPI-linked molecules are susceptible to cleavage by phospholipases such as phospholipase C and phospholipase D [53, 54].

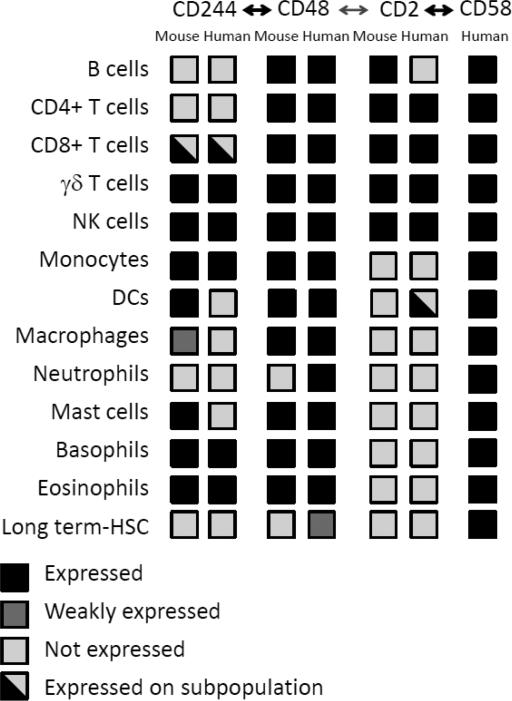

At steady state, CD48 is expressed on nearly all hematopoietic cells (Fig. 2) [3, 7, 19, 39, 55-58]. In fact, the only hematopoietic cell populations in mice that distinctly lack CD48 expression in mice are neutrophils and a subset of long-term hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) [59, 60]. However, in humans CD48 is also found on neutrophils and other HSC types [61, 62].

Figure 2. Comparison of expression of CD48 and ligands in humans and mice.

CD48 has two binding partners, CD244 and CD2. In humans, CD58 (LFA-3) is the high affinity ligand for CD2. CD48 is widely expressed on hematopoetic cells in both mice and humans, while its ligands have more restricted patterns of expression.

CD48 expression increases under inflammatory conditions. Exposure to cytokines such as IFNα, IFNβ and IFNγ can increase CD48 expression on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells [63]. Monocytes and lymphocytes have elevated CD48 expression in patients with viral and bacterial infections [61]. Patients with EBV infection or arthritis exhibit elevated levels of soluble CD48 in the serum [52]. Likewise, CD48 is upregulated in mice in settings of inflammation and infection. During allergic responses, CD48 expression increases on eosinophils [56, 64], while both eosinophils and mast cells can have increased CD48 expression during bacterial infections in mice [65]. In human dendritic cells (DCs), CD48 is upregulated after transfection with double-stranded DNA, a mimic for viral infection [66].

Notably, CD48 is a target of immune evasion by viruses, as well. In murine cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, the mucin-like protein m154 reduces CD48 expression on macrophages, which limits NK cell-mediated control of viral infection [67]. Additionally, homologues of SLAMF members appear in the genomes of some new world monkey CMVs, suggesting novel immune evasion mechanisms. Owl monkey CMV produces a soluble CD48 homologue, which can bind to CD244 and may function as a decoy receptor [68].

CD48 is upregulated in some hematologic malignancies. Hosen et al. found that multiple myeloma cells upregulate CD48, and demonstrated that an anti-CD48 monoclonal antibody (mAb) could deplete multiple myeloma cells in vitro and inhibit growth of multiple myeloma cells in SCID mice [69]. Consistent with these findings, soluble CD48 is increased in the serum of patients with leukemia or lymphoma [52].

5. CD48 ligands

CD48 has multiple binding partners with diverse immunologic functions. CD48 can bind to the lectin FimH on E. coli, facilitating detection and endocytosis of bacteria by macrophages and mast cells [19, 20, 70]. CD48 can also promote interactions between immune cells by binding to CD2 and CD244 on other hematopoietic cells. Mouse CD48 binds CD2 with an affinity of ~90 μM [5]; however, the affinity of CD48 for CD244 is higher (Kd ~ 16 μM) [71]. Similarly, in humans CD48 binds to CD2 with Kd ~100 μM [72], and to CD244 with Kd ~8μM [71]. However, humans (unlike mice) also have the CD58 (LFA-3) gene, which shares homology with CD48 and is the high affinity ligand for CD2 (Kd ~ 9-22 μM) [73, 74].

The CD48 ligands CD2 and CD244 and the CD48 homologue CD58 each have unique expression patterns (Fig. 2). CD2 is predominantly expressed on T and natural killer (NK) cells, although in mice it is also highly expressed on B cells [59, 75-77]. CD244 expression is restricted to NK cells, some memory CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, intraepithelial lymphocytes, monocytes, some dendritic cells and granulocytes [1, 2, 11, 57, 60, 62, 78-83]. CD58 is expressed broadly in humans, both on hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells [59, 84]. Thus, CD48 interactions with its ligands are influenced by the expression patterns of its ligands and CD58, as well as the affinities of these receptor/ligand interactions. The interactions of CD48 with its ligands that predominate in vivo depend on the receptor pairs present on specific cell types, as well as the distinct affinities of each receptor-ligand interaction. Notably, in insect cells transfected with murine CD2 or CD48, CD2 co-expression in CD48+ cells enhanced CD48 interactions with opposing CD2+ cells, suggesting that CD48 and CD2 can interact in cis to influence trans interactions [85].

6. Roles of CD48 in immune cell function and activation

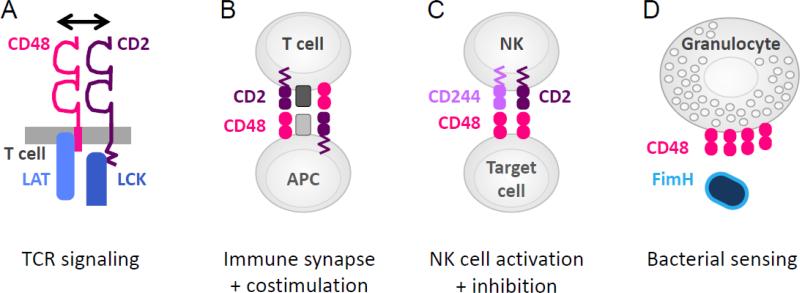

Given the broad expression pattern of CD48, and its increased expression under inflammatory conditions, CD48 is positioned to influence many immunological processes by both cell intrinsic and ligand-receptor actions (Fig. 3). The costimulatory function of CD48 was first identified by the ability of cross-linked anti-CD48 mAb to augment anti-CD3-induced proliferation of murine T cells; stimulation through CD48 alone was not sufficient to induce proliferation [7]. Since then, CD48 has been studied on both T cells and antigen presenting cells (APCs) for its role in T cell activation. The identification of CD244 as an additional binding partner has led to studies of CD48 interactions with both CD2 and CD244 on APCs, NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs).

Figure 3. Functions of CD48.

A. CD48 interactions with CD2 in cis on T cells can promote T cell activation, by facilitating recruitment of signaling components to the TCR. B. CD48 interactions with CD2 in trans contribute to immune synapse organization, adhesion and costimulation. C. CD48 interactions with CD244 can regulate activation of NK cells and CD8+ T effector cells. D. CD48 can bind to the bacterial component FimH, through mannose residues in the GPI linkage of CD48.

6.1 CD48 on T cells regulates T cell signaling

Due to its GPI linkage, CD48 localizes to lipid raft domains in the cell membrane [3, 86]. Since lipid rafts are enriched for both signal transduction molecules and actin cytoskeletal components [87], the localization of CD48 to lipid rafts suggests a possible role for CD48 in T cell signal transduction. Early studies found that CD48 associates with the Src family protein-tyrosine kinase Lck, and that crosslinking CD48 results in Lck phosphorylation in human T cells [88]. Consistent with these findings, CD48 costimulation in mouse T cell lines increased phosphorylation of both Lck and the T cell receptor (TCR) zeta chain and led to association of phosphorylated zeta chain with the cytoskeleton, in a manner dependent on intact lipid rafts. Further studies showed that CD48 physically interacts with Lck [89], and that CD48 crosslinking results in intracellular calcium flux in a cholesterol-dependent mechanism [90] and enhances IL-2 production and TCR signaling, shortening the time of TCR engagement necessary for human T cells to commit to IL-2 production [91]. Taken together, these studies indicate that CD48 on T cells can promote TCR signaling and T cell activation by its association with Lck in lipid rafts.

Further work characterized the molecular mechanism by which CD2 and CD48 enhance early T cell signaling. Drbal et al. found that CD48 becomes immobilized in the immune synapse of anti-CD3-stimulated T cells, while other GPI-linked proteins like CD59 did not [92]. Muhammad et al. showed that when either CD2 or CD48 were lacking from the T cell, there was reduced linker for activation of T cells (LAT) recruitment to the TCR, LAT phosphorylation, calcium flux, and IL-2 production. CD2 was required for CD48 to associate with the TCR and CD3, and CD48 was required for LAT association with the TCR. The authors proposed a model where GPI-linked CD48 interacts in cis with CD2 to efficiently bring Lck and LAT to the TCR/CD3 complex, and thereby facilitate TCR signaling (Fig. 3A) [93]. These studies link molecular interactions of CD48 with signaling components in the T cell, and the resulting influence of CD48 costimulation on IL-2 production. Studies with the CD48−/− [B6.129] mouse are consistent with this model, as CD48−/− T cells have less proliferative potential than wild type (WT) T cells, when stimulated with WT APCs in an allo-mixed lymphocyte reaction [10].

6.2 CD48 on APCs is an adhesion and costimulatory molecule

CD48 also enhances T cell activation through its expression on APCs (Fig. 3B). Latchman et al. found that CD48, when expressed along with the MHC class II molecule I-Ad on CHO cells, enhanced DO11.10 T cell proliferation and IL-2 production compared to CHO cells expressing I-Ad alone or IAd and B7-1, suggesting that CD48 was a strong costimulator. The authors proposed that increased adhesion could be responsible for the increased stimulatory effect since they observed increased T cell-APC conjugates [8]. Consistent with these findings, CD48−/− [B6.129] APCs are less stimulatory to WT T cells, when compared to WT APCs, in an allo-mixed lymphocyte reaction [10].

The function of CD48 on APCs also has been examined from a structural perspective. By creating CD48 mutant molecules with additional IgV regions, Milstein et al. found that the size of CD48 was critical for optimal synapse formation. When the length of CD48 on the APC was increased by two or three IgV domains, CD2 clusters on the T cell were biased towards peripheral regions of the synapse instead of the center of the synapse, and overall CD2-TCR colocalization and T cell proliferation were reduced [9]. These studies highlight how both the size of CD48 and its specificity for CD2 can contribute to its function on APCs to facilitate adhesion and synapse organization.

6.3 CD48 in CTL priming and effector functions

Studies using anti-CD48 and anti-CD2 mAbs suggest that CD48 can regulate effector functions of T cells, including CTLs. When administered at the time of in vivo rechallenge, anti-CD48 limited the contact sensitivity response to TNP. Anti-CD48 also could partially block antigen-specific target cell lysis by CTLs in an in vitro cytotoxicity assay [94]. Both anti-CD2 and anti-CD48 mAbs reduced IL-2Rα expression, IL-2 and IFNγ production, and target lysis by anti-CD3-stimulated bulk T cells in vitro. The reduced target lysis could be rescued by addition of IL-2 [95], suggesting that CD48:CD2 costimulation may stabilize IL-2 mRNA [96]. Thus, CD48:CD2 interactions contribute to both priming and effector functions of CD8+ T cells.

CD244 is expressed on some CD8+ T cells, and likely mediates its effects by interacting with CD48 on other cell types. In a model of inflammatory colitis, CD244 on CD8+ intraepithelial lymphocytes was found to be critical for limiting cytotoxicity [97]. Although CD48 was not examined directly, this suggests that CD244:CD48 interactions may limit CTL differentiation and/or effector functions in the gut. CD244 is also implicated in CD8+ T cell memory and exhaustion. CD244 is highly expressed on dysfunctional CD8+ T cells in chronic infection and cancer models [98]. A functional role for CD244 on CD8+ memory T cells has been described during chronic viral infection; CD244 was critical for limiting persistence of CD8+ memory T cells [99]. However, it is not yet clear how CD48 contributes in each of these roles. For example, CD48 expression on neighboring CTLs is sufficient to enhance CD244-mediated cytotoxicity, even with CD48-negative target cells [17].

CD48:CD244 interactions have also been examined in vitro. CD48 expression on human dendritic cells increased after stimulation with cytosolic DNA (by transfection of dsDNA). DC CD48 engagement by CD244 on CD8+ T cells prolonged survival of the dendritic cells by inhibiting IFN-β production, and IFN-β mediated apoptosis of mature DC, as well as promoting production of the granzyme B inhibitor PI-9, thereby increasing the effective time for T cell activation [66]. Collectively, these studies suggest that CD244 can modulate many aspects of CD8+ T cell function, likely by interactions with CD48 on APCs, neighboring CD8+ T cells, or target cells, and that these may have differing outcomes during different phases of the immune response.

6.4 Ligand interactions with CD244 on NK cells

As the exclusive binding partner of CD244, CD48 can induce signaling through the ITSMs of CD244 (Fig. 3C). On NK cells, CD244 has been described as both an activating and inhibitory receptor, either promoting or inhibiting target lysis [11-15]. One consideration in mouse NK cells is the relative expression of two isoforms of CD244, which differ in the length of their cytoplasmic tails. The long form is inhibitory and the short form is stimulatory [12]. Stimulation also depends on the density of CD244 on the cell surface, the degree of crosslinking, and the amount of the signaling molecule SAP: high surface expression, strong crosslinking and low levels of SAP are associated with inhibitory effects [15]. Some studies suggest that signaling through EAT-2 promotes inhibitory effects, whereas signaling via SAP-Fyn promotes activation and target lysis [100]. This mechanism is supported by studies of NK cells lacking SAP or Fyn, which show defects in lysis of CD48+ targets [101]. However, signaling through EAT-2 can also result in positive signals involving phospholipase C [16]. Furthermore, Wang et al. found that EAT-2A and 2B deficiency in B6 mice resulted in a defect in CD244-dependent lysis by NK cells, which was in contrast to prior studies examining EAT-2A and 2B deficiency on the 129Sv genetic background [100, 102] and may reflect polymorphisms in SLAM family members in the B6 and 129 strain backgrounds, and/or presence of a drug selection marker in the 129Sv mice. Thus, while CD244 can influence NK cell cytotoxicity through multiple independent factors, the molecular mechanisms are not yet fully elucidated. In addition, CD2 on NK cells can compete with CD244 for binding to CD48 on target cells, thus providing additional influences on NK cell activation [16].

CD48 also can influence CD244-mediated killing, although this does not always depend on CD48 expression on the target cell. In NK cells, Taniguchi et al. propose a mechanism whereby CD244-CD48 interactions between NK cells can prevent NK cell fratricide [18]. Waggoner et al. found that CD244−/− mice were more susceptible to chronic infection with lymphocyte choriomeningitis virus, due to enhanced NK-mediated lysis of activated CD44+ CD8+ T effectors [103]. It remains to be determined how CD48 plays a role in this CD244-dependent effect.

In addition, anti-CD48 mAb administration in vivo can increase surface expression of CD244 and CD69, and induce cytokine production in NK cells [104, 105]. Moreover, anti-CD48 in vivo influences B cell responses to T independent antigens. Administration of anti-CD48 prior to immunization with the T-independent antigen NP-Ficoll enhanced production of IgG1 and IgG2a in an NK-cell dependent fashion in B6 mice, suggesting that anti-CD48 may alter NK interactions with B cells that impact antibody responses [105].

6.5 As a ligand for FimH on bacteria

CD48 binds to the bacterial lectin FimH through the mannose sugar residues in its GPI linkage (Fig. 3D) [19]. On mast cells, FimH binding to CD48 can trigger the mast cell TNFα response [106] and phagocytosis [70, 107]. On macrophages, FimH binding to CD48 leads to an opsonin-free mechanism for phagocytosis of bacteria. This involves formation of caveolae in cholesterol-rich domains of the cell membrane, and facilitates entry of the microbe into macrophages [19, 20, 108]. This mechanism may be particularly relevant for phagocytosis of FimH+ bacteria that have not yet been opsonized, but have adhered to tissue surfaces [20].

The ability of FimH to bind to CD48 also has implications for bacterial invasion of endothelial cells. FimH on E. coli K1 can bind to CD48 on cultured human brain microvascular endothelial cells, thereby promoting bacterial adhesion and inducing cellular changes in the endothelial cells that facilitate bacterial invasion [109].

These studies highlight a cell intrinsic role for CD48 on monocytes and granulocytes, which may be especially important in mucosal immunity and infection.

7. Immunoregulatory roles for CD48 determined by studies in models of human diseases

Studies in models of human immune-mediated diseases have revealed roles for CD48 and its ligands in autoimmunity, inflammation, allergy, infection, graft rejection, and hematopoiesis.

7.1 CD48−/− mouse strains and spontaneous autoimmunity

Mouse strains containing SLAM haplotype 2 alleles on a B6 genetic background develop features of lupus. For example, B6 congenic mice that carry the 129-derived version of chromosome 1 in the region containing the SLAM family genes spontaneously develop autoantibodies [110]. However, a more aggressive form of disease with both spontaneous anti-DNA autoantibodies and severe glomerulonephritis is observed at 3-6 months of age in CD48−/− [B6.129] mice, which were made by gene targeting in a 129-derived ES cell and backcrossing to B6 [47]. This disease is also more severe than that observed in other SLAMF-deficient mice, such as CD150−/− [B6.129], suggesting that CD48 may play an immunoregulatory role in this model of lupus [47]. Notably, CD48−/− [Balb/c.129] mice do not develop signs of autoimmunity, suggesting that CD48 deficiency alone does not precipitate autoimmunity [47]. However, CD48−/− [Balb/c.129] mice do exhibit defects in induction of tolerance in vivo [47]. Collectively, these observations suggest that CD48 can have an immunoregulatory role in the presence and absence of an autoimmune-prone genetic background.

7.2. CD48 on macrophages and T cells in a model of inflammatory colitis

CD48 on both T cells and macrophages plays a critical regulatory role in the CD45RBhi cells adoptive transfer model of experimental colitis, in which CD45RBhi T cells elicit colitis when transferred to RAG−/− recipients [111]. Loss of CD48 on either the donor T cells or in the recipient was insufficient to prevent colitis. However, CD48−/− [Balb/c.129] T cells failed to induce disease in CD48−/− RAG−/− recipients. The absence of CD48 on either the APC or the T cell reduced IL-2 production in vitro, but this was most dramatic when CD48 was absent on both the T cell and the APC. Anti-CD48 mAb administration attenuated colitis when given before or after disease onset [111], suggesting that CD48 may be a therapeutic target for inflammatory bowel disease.

In addition, CD48 deficiency on peritoneal macrophages impaired their response to bacterial components. Specifically, CD48−/− macrophages exhibited impaired TNFα and IL-12 production in response to LPS in vitro and stimulated WT T cells more poorly compared to WT peritoneal macrophages [111]. These findings suggest CD48 may play a cell intrinsic role on innate immune cells in response to bacteria.

7.3 CD2 peptide derivatives to block CD48 in arthritis

With the aim of attenuating autoimmunity by disrupting a key costimulatory interaction, Gokhale and colleagues developed CD2 peptide derivatives for therapeutic use in collagen-induced arthritis. These compounds contain a peptide from the CD2 protein along with stabilizing moieties, and can interact with both human CD58 and mouse CD48 [112]. The compounds limit staining of CD58+ cells with an anti-CD58 mAb, indicating the specificity of the compound; however, the authors did not report specifically on whether the compounds blocked interactions between CD58 and CD2. Administration of these CD2 peptides during collagen-induced arthritis in the DBA mouse attenuated both clinical and histological signs of disease [112, 113]. These studies highlight the relevance of the CD2:CD48 and CD2:CD58 pathways during ongoing autoimmunity, and their potential as therapeutic targets.

7.4 CD48 on eosinophils in allergy and asthma

CD48 controls activation of both human and mouse eosinophils. The asthma-susceptibility gene ORMDL3 regulates IL-3-induced CD48 expression in eosinophils, as well as CD48-mediated degranulation [114]. CD48 expression is increased on eosinophils from patients with atopic asthma or from mice after allergen challenge [64]. Moreover, crosslinking CD48 on cultured eosinophils leads to degranulation. Human eosinophils also express CD244 and SAP, and crosslinking CD244 results in production of eosinophil peroxidase, IFNγ and IL-4 [115].

Studies in a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation demonstrate a regulatory role for CD48. Munitz et al. found that in vivo administration of anti-CD48 mAb one day before antigen challenge dramatically reduced inflammation, lung cell infiltration, cytokines, and histological signs of inflammation, while anti-CD2 or anti-CD244 mAbs had no such effect. The authors did not observe depletion of lymphocytes in the spleen, or alterations to eosinophils in the bone marrow, but did see reduced eosinophils in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [56].

CD48 and CD244 can mediate interactions between eosinophils and mast cells in vitro, allowing eosinophils to costimulate IgE-mediated activation of mast cells [80]. Collectively, these studies suggest that CD48 may be a viable target for therapy in allergy and asthma.

7.5 CD48 on granulocytes in bacterial infection

CD48 has been implicated in responses to bacteria in multiple models of infection. CD48 surface expression increased along with Toll-like receptor 2 expression on human cord blood-derived mast cells after infection with Staphylococcus aureus in vitro. Blocking CD48 with an anti-CD48 mAb reduced the inflammatory responses of these cells [65], supporting a cell intrinsic role for CD48 in response to infection.

In addition, CD48 regulates the response of eosinophils to S. aureus. Eosinophils degranulate and produce IL-8 and IL-10 after exposure to S. aureus, and a CD48 blocking antibody prevents this degranulation. Furthermore, eosinophils from CD48−/− [B6.129] mice do not perform these functions as well as WT eosinophils. In a model of peritonitis induced by intraperitoneal injection of Staphylococcal toxin B (SEB), CD48−/− [B6.129] mice had reduced numbers of eosinophils and granulocytes in peritoneal lavage fluid, but no reduction in lymphocytes, when compared to WT mice [116]. These studies indicate that CD48 can contribute to bacterial sensing and granulocyte activation during infection.

7.6 CD48 and graft rejection

CD2 is a strong target for allogeneic responses, and anti-CD2 antibody therapies facilitate graft survival in numerous mouse models [117, 118]. Anti-CD2 plus anti-CD48 mAb administration in vivo allowed indefinite cardiac allograft survival, while administration of either antibody alone had milder effects on graft survival [117]. Anti-CD244 mAb did not enhance the effects of either anti-CD2 or anti-CD48 [119]. Although anti-CD2 plus anti-CD48 were much more effective than either antibody alone, anti-CD48 could limit both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses. In addition, anti-CD48 in combination with anti-LFA1 mAb and FTY720 could enable survival of embryonic pig pancreatic tissue transplanted into mice [120]. Thus, CD48 blockade can promote graft survival when part of combination therapies.

7.7 CD48 in hematopoiesis

A role for CD48 in hematopoiesis was first suggested by studies using an anti-CD48 mAb to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Following sublethal irradiation and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT), combined use of anti-CD48 plus anti-CD2 mAbs prevented GVHD but also prevented recovery of the hematopoietic compartment. Anti-CD48 prevented bone marrow reconstitution after congenic BMT, which is likely due to altered CD48 expression following antibody treatment. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that CD48 expression is critical for hematopoietic recovery after sublethal irradiation [121].

Hematopoiesis also has been studied in CD48−/− [B6.129] mice. These mice have a dysregulated hematopoietic stem cell compartment and a propensity towards follicular B cell-type lymphomas. Boles et al. observed altered distribution of monocyte and lymphocyte precursors in the bone marrow of CD48−/− [B6.129] mice and a reduced proliferative capacity of CD48−/− HSCs. Aged CD48−/− mice had an increased incidence of lymphoma, which correlated with upregulated Pak1 activity in CD19+ tumor cells but not in CD19+ cells from the spleen [122]. Whether altered hematopoiesis and increased incidence of tumors in CD48−/− [B6.129] mice is due to CD48 intrinsic effects, or interactions between 129- and B6-derived genes, remains to be determined.

8. CD48 and CD58 in human disease

Although CD48 is the only known ligand for CD2 in mice, in humans CD58 (LFA-3) is the high affinity ligand for CD2 [72, 73, 123, 124] and may have some overlapping roles with that of CD48 in mice. Here we discuss evidence for the roles of CD48 and CD58 in human disease states.

8.1 CD48, CD58 and demyelinating diseases

Genome-wide association scans identified CD58 as a risk locus in MS, with a protective allele that results in increased CD58 mRNA in PBMCs [125, 126]. Notably, CD58 expression also increases during remissions in MS patients [125, 127]. De Jager et al. proposed that increased expression of CD58 results in increased engagement of CD2, which leads to increased Foxp3 expression. CD58 polymorphisms also have been associated with neuromyelitis optica (NMO), a demyelinating disease that primarily affects the optic nerve and spinal cord. Two haplotypes and four alleles showed an association with NMO, by TaqMan analysis, but no functional studies were performed [128]. In a separate protein-interaction-network-based pathway analysis in MS, CD48 was among a small group of high confidence candidates [51].

8.2 CD58 in autoimmunity

Alefacept is a CD58-Ig fusion protein that binds to human CD2. Alafacept was used for treatment of plaque psoriasis [129] until the manufacturer discontinued production and sales in 2011, citing business needs [130, 131]. CD58-Ig has multiple immunosuppressive effects on T cells, including depletion of memory cells and inhibition of T cell activation [132, 133]. The potential of alefacept to influence T cell activation led to its investigation in limiting other T cell mediated conditions including transplant rejection and certain autoimmune diseases. When combined with CTLA-4-Ig, alefacept promoted allograft survival in a kidney transplantation model in macaques [134]. In a recent description of trials initiated before the drug was discontinued, alefacept showed positive effects in preserving pancreatic beta cell function when administered in early onset type 1 diabetes [135, 136]. In a 24-week trial, alefacept improved clinical readouts, such as reduced insulin use and reduced numbers of extreme hypoglycemic events, and depleted CD4+ and CD8+ central and effector memory cells, but preserved Tregs, thereby increasing the ratio of CD4+ Tregs to memory T cells in the blood [135]. These studies highlight the role of the CD2-CD58-CD48 pathway in modulating T cell mediated inflammation in patients.

8.3 CD48 and CD244 in viral infections

As the counter-receptor for CD244 on NK and CD8+ T cells, CD48 has been studied in human viral infections. CD48 expression increases on B cells during Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection [55]. EBV infection is particularly dangerous for patients with X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome 1 (XLP-1), a disease resulting from mutation of the SH2D1A gene that encodes the signaling molecule SAP—a crucial adaptor for CD244 signaling in NK cells [34]. In patients with XLP-1, NK cells are unable to kill EBV+ B cells or to control EBV infection, due to a lack of activation of SAP-deficient NK cells upon engagement of CD48+ targets [137, 138]. Notably, EBV+ B cells do not express ligands for the activating NK receptors DNAM-1 and NKG2a, rendering these cells particularly sensitive to CD244-mediated lysis by NK cells [139]. Similarly, SAP-deficient CD8+ T cells can be activated by most types of APCs, but fail to be activated by antigen-presenting B cells—and EBV selectively infects B cells [140]. Thus, SAP deficiency in T cells leads to altered interactions with B cells but not other types of APCs, and this may explain the selective susceptibility of XLP-1 patients to EBV infection, but not to viral infections in general.

Studies of other viral infections suggest CD48 may regulate CTL and NK cell activity. For example, CD48 and NTB-A (SLAMF6) are downregulated on HIV-infected T cell blasts, which could potentially limit the ability of NK and CD8+ T cells to lyse infected target cells [141]. It is not yet clear how CD48 levels on target cells influence cytotoxicity, as CD244:CD48 interactions have been shown to either enhance or inhibit cytotoxicity of NK and CD8+ T cells, depending on the context [142]. For example, CD244 crosslinking—with either CD48-expressing target cells or anti-CD244 mAbs—is stimulatory when CD244 expression is low or SAP is abundant, but inhibitory when CD244 expression is high or SAP is rare [15, 143]. In addition, CD244 expression on virus-specific CD8+ T cells decreased after simultaneous TCR and CD244 signaling, suggesting that binding to CD48 could influence CD244 expression [144].

9. Conclusions

The broad expression of CD48, together with the limited tools for studying its function, pose challenges for elucidating its immunoregulatory functions. Despite these difficulties, we have learned that CD48 is involved in a wide variety of innate and adaptive immune responses, ranging from granulocyte activity and allergic inflammation, to T cell activation and autoimmunity, to CTL or NK function and antimicrobial immunity. However, further work is needed to understand its critical immunoregulatory roles and its potential as a therapeutic target.

While it is clear that CD48 contributes to T cell activation and proliferation, further studies are needed to determine the unique and redundant functions of CD48. Many adhesion molecules contribute to formation and organization of the immune synapse; however, combined blockade of CD48 and other adhesion molecules may have more profound effects on T cell activation. For example, the combination of anti-CD48 mAb, anti-LFA-1 mAb and FTY720, led to long-term graft maintenance in a model of pig embryonic pancreatic tissue transplantation into mice [120]. Thus, CD48 may be a valuable target in combination therapies that suppress pathogenic immune responses.

Some studies indicate a role for CD48 in promoting T cell tolerance, and further work is needed to understand how CD48 can promote both T cell activation and tolerance. T cells from CD48−/− mice are defective in inducing antigen-specific tolerance in vivo, although the mechanism by which this defect occurs, and whether it is T cell intrinsic, have not been elucidated [47]. Increased expression of CD58 is associated with both increased Foxp3 expression in Tregs and remission of MS [125]. Thus, there may be positive roles for CD2 ligands—such as CD48 and CD58—in promoting tolerance. One potential hypothesis is that there are distinct outcomes of CD48 interactions with different binding partners on specific cell types at different phases of immune responses. Conditional knockout mice that lack CD48 on specific cell types will be valuable for evaluating the roles of CD48 on T cell subsets and APCs.

In the realm of allergy and asthma, CD48 serves as a biomarker for activated granulocytes and promotes granulocyte degranulation [64]. Interactions between CD48 and CD244 on mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils suggest that these cell types can act synergistically in the ‘allergic effector unit’ to promote inflammation. The observation that anti-CD48 mAb treatment significantly reduced airway inflammation in an allergy model strongly suggests that this molecule has clinical relevance [56]. In exploration of therapeutic avenues, additional mAb tools are needed to compare the effects of blocking, activating, and depleting isotypes and guide development of reagents for clinical use.

The high affinity ligand for CD48, CD244, is highly expressed on dysfunctional T cells in chronic viral infections and cancer [98]. While a functional role for CD244 in T cell exhaustion has been demonstrated in at least one model of infection [99], it is not yet clear if or how CD48 contributes to this phenotype. Further work is needed to determine if CD48 has a cell intrinsic function in hematologic malignancies. Because of the broad expression of CD48, CD244 may interact with CD48 on neighboring NK cells, T cells, or even with APCs. CD48 conditional knockout mice will help to rigorously assess these key players and identify the cellular interactions that contribute to T cell exhaustion in tumors and viral infections.

In summary, we have learned a great deal about the roles for CD48 in numerous disease models, and on multiple cell types, but have much more to discover. Because CD48 expression is upregulated upon activation in multiple cell types, the temporal elements of CD48-directed intervention also will be useful to explore. A better understanding of the roles of CD48 and its ligands on specific cell types will enable us to translate this knowledge to therapy.

Table 1.

Roles of CD48 in animal models of disease

| Disease | Animal Model | Effects of CD48 blockade or deficiency | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmunity | Lupus | Development of spontaneous lupus-like disease in CD48−/− mice or a mixed 129-B6 background | [47] |

| Colitis | Anti-CD48 blocking mAb ameliorates colitis in the CD45RBhi transfer model; CD48−/− mice show reduced severity of colitis; demonstrate roles for CD48 on T cells and macrophages in regulating colitis | [111] | |

| Arthritis | CD2-derived peptides that bock CD2 interactions with CD48 can attenuate collagen-induced arthritis in DBA mice | [112, 113] | |

| Allergy | Asthma | CD48 expression increases on eosinophils after sensitization and challenge in an OVA model of experimental asthma in mice; anti-CD48 mAb limits eosinophils in the lung after rechallenge | [56, 64] |

| Contact sensitivity | Anti-CD48 mAb reduces contact sensitivity response to trinitrophenol; limits generation of TNP-specific CTLs in vivo | [94] | |

| Infection | S. aureus | CD48−/− mice have fewer eosinophils and granulocytes in the peritoneum during Staphylococcal enterotoxin B-induced peritonitis | [116] |

| LCMV | CD244−/− CD8+ T cells have increased memory CD8+ T cell survival during chronic LCMV infection | [99] | |

| CMV | Murine CMV reduces CD48 expression in infected macrophages via the viral protein m154, thereby limiting NK cell control of infection | [67] | |

| Owl monkey CMV includes a gene for a soluble homologue of CD48, which binds to CD244 and may act as a decoy receptor | [68] | ||

| CpG | Increased perforin-dependent killing of NK cells by NK cells after CpG injection in CD244−/− mice, indicating regulatory role for CD48:CD244 in limiting NK fratricide | [18] | |

| E. coli | CD48 is a receptor for the adhesin FimH, found on type 1 fimbriated E. coli; CD48:FimH interactions stimulate mouse mast cells and macrophages to produce TNFα and phagocytose bacteria | [19, 20, 70, 106] | |

| Transplantation | Solid organ - Heart | Anti-CD48 mAb contributes to graft survival, along with anti-CD2 mAb | [117] |

| Solid organ - Islet | Combination therapy with anti-CD48 mAb, FTY720 and anti-LFA-1 mAb promotes pig islet allograft survival in mice | [120] | |

| Solid organ - Kidney | Combination therapy with CD58-Ig and anti-CTLA-4 mAb promotes kidney allograft survival in macaques | [134] | |

| Bone marrow - Allogeneic | Anti-CD48 mAb limits allogeneic bone marrow reconstitution after sublethal irradiation | [121] | |

| Cancer | B cell lymphoma | CD48−/− [B6.129] have altered HSCs and increased frequency of B cell lymphomas | [122] |

| Multiple-myeloma | Anti-human CD48 mAb depletes human-derived multiple-myeloma in mice | [69] | |

Table 2.

Association of CD48 and CD58 with human immunity and disease.

| Disease | Type of Study | Observations | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmunity | Genetic | CD58 identified as a risk locus for MS, using GWAS | [126] |

| The protective allele for CD58 results in increased CD58 mRNA in PBMCs | [125] | ||

| Polymorphisms in the CD58 gene are associated with risk for NMO | [128] | ||

| CD48 identified as candidate susceptibility gene by network-based MS pathway analysis | [51] | ||

| Expression | Soluble CD48 is increased in the serum of patients with arthritis | [52] | |

| CD58 mRNA expression in PBMCs increases during remission in MS patients | [125, 127] | ||

| Function | CD58-Ig ameliorates chronic plaque psoriasis | [129, 132] | |

| CD58-Ig depletes effector-memory cells, preserves central memory cells in psoriasis vulgaris | [133, 145] | ||

| CD58-Ig (alefacept) improve symptoms in early-onset diabetes | [135, 136] | ||

| Allergy | Genetic | The asthma-susceptibility gene ORMDL3 regulates CD48-mediated degranulation in eosinophils | [114] |

| Expression | CD48 is increased on eosinophils from blood or nasal polyps in atopic asthma patients | [64] | |

| CD48 is increased on eosinophils in skin of patients with atopic dermatitis | [116] | ||

| Infection | Expression | CD48 expression increases on monocytes and lymphocytes in the blood during a number of viral and bacterial infections, including varicella, measles, streptococcus tonsillitis | [61] |

| CD48 surface expression increases on EBV-infected B cells | [55] | ||

| Soluble CD48 is increased in the serum of patients with EBV | [52] | ||

| CD48 expression increases on DCs after transfection with DNA | [66] | ||

| CD48 expression increases on cord-blood derived mast cells infected with S. aureus | [65] | ||

| CD48 expression decreases on primary T cell blasts during HIV infection | [141] | ||

| Function | Blood eosinophils are activated by S. aureus endotoxins in a CD48-dependent manner | [116] | |

| Anti-CD48 mAb limits inflammatory response of cord blood-derived mast cells to S. aureus, in vitro | [65] | ||

| Cancer | Expression | Soluble CD48 increases in the serum of patients with leukemia or lymphoma | [52] |

| Increased surface CD48 expression on multiple myeloma plasma cells | [69] | ||

| Decreased surface CD48 in acute myeloid leukemia, due to repression by AML1-ETO | [146] | ||

Highlights.

CD48 is constitutively expressed on hematopoietic cells, and upregulated on specific subsets during allergy, infection, and malignancy

CD48:CD2 interactions promote immune synapse organization, adhesion, and TCR signaling

CD48:CD244 interactions control NK and CTL activation and cytolytic function

Multiple studies suggest that CD48 and CD58 are valuable therapeutic targets in human disease

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant PO1 AI065687. We thank Drs. Daniel Brown and Kathleen McGuire for their thoughtful comments. Because of space restrictions, we were able to cite only a fraction of the relevant literature and we apologize to colleagues whose contributions may not be acknowledged in this review. This work benefited from data assembled by the ImmGen consortium.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Calpe S, Wang N, Romero X, Berger SB, Lanyi A, Engel P, Terhorst C. The SLAM and SAP Gene Families Control Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. 2008;97:177–250. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannons JL, Tangye SG, Schwartzberg PL. SLAM family receptors and SAP adaptors in immunity. Annual review of immunology. 2011;29:665–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staunton DE, Fisher RC, LeBeau MM, Lawrence JB, Barton DE, Francke U, Dustin M, Thorley-Lawson DA. Blast-1 possesses a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane anchor, is related to LFA-3 and OX-45, and maps to chromosome 1q21-23. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1989;169:1087–1099. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong YW, Williams AF, Kingsmore SF, Seldin MF. Structure, expression, and genetic linkage of the mouse BCM1 (OX45 or Blast-1) antigen. Evidence for genetic duplication giving rise to the BCM1 region on mouse chromosome 1 and the CD2/LFA3 region on mouse chromosome 3. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1990;171:2115–2130. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.6.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis SJ, van der Merwe PA. The structure and ligand interactions of CD2: implications for T-cell function. Immunology today. 1996;17:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorley-Lawson DA, Poodry CA. Identification and isolation of the main component (gp350-gp220) of Epstein-Barr virus responsible for generating neutralizing antibodies in vivo. Journal of virology. 1982;43:730–736. doi: 10.1128/jvi.43.2.730-736.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato K, Koyanagi M, Okada H, Takanashi T, Wong YW, Williams AF, Okumura K, Yagita H. CD48 is a counter-receptor for mouse CD2 and is involved in T cell activation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1992;176:1241–1249. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Latchman Y, McKay PF, Reiser H. Identification of the 2B4 molecule as a counter-receptor for CD48. Journal of immunology. 1998;161:5809–5812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milstein O, Tseng SY, Starr T, Llodra J, Nans A, Liu M, Wild MK, van der Merwe PA, Stokes DL, Reisner Y, Dustin ML. Nanoscale increases in CD2-CD48-mediated intermembrane spacing decrease adhesion and reorganize the immunological synapse. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:34414–34422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804756200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Cabrero J, Wise CJ, Latchman Y, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Reiser H. CD48-deficient mice have a pronounced defect in CD4(+) T cell activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:1019–1023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garni-Wagner BA, Purohit A, Mathew PA, Bennett M, Kumar V. A novel function-associated molecule related to non-MHC-restricted cytotoxicity mediated by activated natural killer cells and T cells. Journal of immunology. 1993;151:60–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schatzle JD, Sheu S, Stepp SE, Mathew PA, Bennett M, Kumar V. Characterization of inhibitory and stimulatory forms of the murine natural killer cell receptor 2B4. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:3870–3875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee KM, McNerney ME, Stepp SE, Mathew PA, Schatzle JD, Bennett M, Kumar V. 2B4 acts as a non-major histocompatibility complex binding inhibitory receptor on mouse natural killer cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2004;199:1245–1254. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaidya SV, Stepp SE, McNerney ME, Lee JK, Bennett M, Lee KM, Stewart CL, Kumar V, Mathew PA. Targeted disruption of the 2B4 gene in mice reveals an in vivo role of 2B4 (CD244) in the rejection of B16 melanoma cells. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:800–807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chlewicki LK, Velikovsky CA, Balakrishnan V, Mariuzza RA, Kumar V. Molecular basis of the dual functions of 2B4 (CD244) Journal of immunology. 2008;180:8159–8167. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarkson NG, Brown MH. Inhibition and activation by CD244 depends on CD2 and phospholipase C-gamma1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:24725–24734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.028209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KM, Bhawan S, Majima T, Wei H, Nishimura MI, Yagita H, Kumar V. Cutting edge: the NK cell receptor 2B4 augments antigen-specific T cell cytotoxicity through CD48 ligation on neighboring T cells. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:4881–4885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taniguchi RT, Guzior D, Kumar V. 2B4 inhibits NK-cell fratricide. Blood. 2007;110:2020–2023. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-076927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baorto DM, Gao Z, Malaviya R, Dustin ML, van der Merwe A, Lublin DM, Abraham SN. Survival of FimH-expressing enterobacteria in macrophages relies on glycolipid traffic. Nature. 1997;389:636–639. doi: 10.1038/39376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moller J, Luhmann T, Chabria M, Hall H, Vogel V. Macrophages lift off surface-bound bacteria using a filopodium-lamellipodium hook-and-shovel mechanism. Scientific reports. 2013;3:2884. doi: 10.1038/srep02884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin M, Romero X, de la Fuente MA, Tovar V, Zapater N, Esplugues E, Pizcueta P, Bosch J, Engel P. CD84 functions as a homophilic adhesion molecule and enhances IFN-gamma secretion: adhesion is mediated by Ig-like domain 1. Journal of immunology. 2001;167:3668–3676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flaig RM, Stark S, Watzl C. Cutting edge: NTB-A activates NK cells via homophilic interaction. Journal of immunology. 2004;172:6524–6527. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao E, Ramagopal UA, Fedorov A, Fedorov E, Yan Q, Lary JW, Cole JL, Nathenson SG, Almo SC. NTB-A receptor crystal structure: insights into homophilic interactions in the signaling lymphocytic activation molecule receptor family. Immunity. 2006;25:559–570. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falco M, Marcenaro E, Romeo E, Bellora F, Marras D, Vely F, Ferracci G, Moretta L, Moretta A, Bottino C. Homophilic interaction of NTBA, a member of the CD2 molecular family: induction of cytotoxicity and cytokine release in human NK cells. European journal of immunology. 2004;34:1663–1672. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumaresan PR, Lai WC, Chuang SS, Bennett M, Mathew PA. CS1, a novel member of the CD2 family, is homophilic and regulates NK cell function. Molecular immunology. 2002;39:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mavaddat N, Mason DW, Atkinson PD, Evans EJ, Gilbert RJ, Stuart DI, Fennelly JA, Barclay AN, Davis SJ, Brown MH. Signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (CDw150) is homophilic but self-associates with very low affinity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:28100–28109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Punnonen J, Cocks BG, Carballido JM, Bennett B, Peterson D, Aversa G, de Vries JE. Soluble and membrane-bound forms of signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM) induce proliferation and Ig synthesis by activated human B lymphocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1997;185:993–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.6.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero X, Zapater N, Calvo M, Kalko SG, de la Fuente MA, Tovar V, Ockeloen C, Pizcueta P, Engel P. CD229 (Ly9) lymphocyte cell surface receptor interacts homophilically through its N-terminal domain and relocalizes to the immunological synapse. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:7033–7042. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan Q, Malashkevich VN, Fedorov A, Fedorov E, Cao E, Lary JW, Cole JL, Nathenson SG, Almo SC. Structure of CD84 provides insight into SLAM family function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:10583–10588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703893104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kingsbury GA, Feeney LA, Nong Y, Calandra SA, Murphy CJ, Corcoran JM, Wang Y, Prabhu Das MR, Busfield SJ, Fraser CC, Villeval JL. Cloning, expression, and function of BLAME, a novel member of the CD2 family. Journal of immunology. 2001;166:5675–5680. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fraser CC, Howie D, Morra M, Qiu Y, Murphy C, Shen Q, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Coyle A, Kingsbury GA, Terhorst C. Identification and characterization of SF2000 and SF2001, two new members of the immune receptor SLAM/CD2 family. Immunogenetics. 2002;53:843–850. doi: 10.1007/s00251-001-0415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fennelly JA, Tiwari B, Davis SJ, Evans EJ. CD2F-10: a new member of the CD2 subset of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:599–602. doi: 10.1007/s002510100364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W, Wan T, Li N, Yuan Z, He L, Zhu X, Yu M, Cao X. Genetic approach to insight into the immunobiology of human dendritic cells and identification of CD84-H1, a novel CD84 homologue. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2001;7:822s–829s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sayos J, Wu C, Morra M, Wang N, Zhang X, Allen D, van Schaik S, Notarangelo L, Geha R, Roncarolo MG, Oettgen H, De Vries JE, Aversa G, Terhorst C. The X-linked lymphoproliferative-disease gene product SAP regulates signals induced through the co-receptor SLAM. Nature. 1998;395:462–469. doi: 10.1038/26683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morra M, Lu J, Poy F, Martin M, Sayos J, Calpe S, Gullo C, Howie D, Rietdijk S, Thompson A, Coyle AJ, Denny C, Yaffe MB, Engel P, Eck MJ, Terhorst C. Structural basis for the interaction of the free SH2 domain EAT-2 with SLAM receptors in hematopoietic cells. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:5840–5852. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shlapatska LM, Mikhalap SV, Berdova AG, Zelensky OM, Yun TJ, Nichols KE, Clark EA, Sidorenko SP. CD150 association with either the SH2-containing inositol phosphatase or the SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase is regulated by the adaptor protein SH2D1A. Journal of immunology. 2001;166:5480–5487. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li SC, Gish G, Yang D, Coffey AJ, Forman-Kay JD, Ernberg I, Kay LE, Pawson T. Novel mode of ligand binding by the SH2 domain of the human XLP disease gene product SAP/SH2D1A. Current biology : CB. 1999;9:1355–1362. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poy F, Yaffe MB, Sayos J, Saxena K, Morra M, Sumegi J, Cantley LC, Terhorst C, Eck MJ. Crystal structures of the XLP protein SAP reveal a class of SH2 domains with extended, phosphotyrosine-independent sequence recognition. Molecular cell. 1999;4:555–561. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokoyama S, Staunton D, Fisher R, Amiot M, Fortin JJ, Thorley-Lawson DA. Expression of the Blast-1 activation/adhesion molecule and its identification as CD48. Journal of immunology. 1991;146:2192–2200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morel L, Rudofsky UH, Longmate JA, Schiffenbauer J, Wakeland EK. Polygenic control of susceptibility to murine systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunity. 1994;1:219–229. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohan C, Alas E, Morel L, Yang P, Wakeland EK. Genetic dissection of SLE pathogenesis. Sle1 on murine chromosome 1 leads to a selective loss of tolerance to H2A/H2B/DNA subnucleosomes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;101:1362–1372. doi: 10.1172/JCI728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morel L, Blenman KR, Croker BP, Wakeland EK. The major murine systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility locus, Sle1, is a cluster of functionally related genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:1787–1792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031336098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wandstrat AE, Nguyen C, Limaye N, Chan AY, Subramanian S, Tian XH, Yim YS, Pertsemlidis A, Garner HR, Jr., Morel L, Wakeland EK. Association of extensive polymorphisms in the SLAM/CD2 gene cluster with murine lupus. Immunity. 2004;21:769–780. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bygrave AE, Rose KL, Cortes-Hernandez J, Warren J, Rigby RJ, Cook HT, Walport MJ, Vyse TJ, Botto M. Spontaneous autoimmunity in 129 and C57BL/6 mice-implications for autoimmunity described in gene-targeted mice. PLoS biology. 2004;2:E243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar KR, Li L, Yan M, Bhaskarabhatla M, Mobley AB, Nguyen C, Mooney JM, Schatzle JD, Wakeland EK, Mohan C. Regulation of B cell tolerance by the lupus susceptibility gene Ly108. Science. 2006;312:1665–1669. doi: 10.1126/science.1125893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keszei M, Detre C, Rietdijk ST, Munoz P, Romero X, Berger SB, Calpe S, Liao G, Castro W, Julien A, Wu YY, Shin DM, Sancho J, Zubiaur M, Morse HC, 3rd, Morel L, Engel P, Wang N, Terhorst C. A novel isoform of the Ly108 gene ameliorates murine lupus. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:811–822. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keszei M, Latchman YE, Vanguri VK, Brown DR, Detre C, Morra M, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Paul E, Calpe S, Castro W, Wang N, Terhorst C, Sharpe AH. Auto-antibody production and glomerulonephritis in congenic Slamf1−/− and Slamf2−/− [B6.129] but not in Slamf1−/− and Slamf2−/− [BALB/c.129] mice. International immunology. 2011;23:149–158. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cabrero JG, Freeman GJ, Reiser H. The murine Cd48 gene: allelic polymorphism in the IgV-like region. European journal of immunogenetics : official journal of the British Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics. 1998;25:421–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2370.1998.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Limaye N, Belobrajdic KA, Wandstrat AE, Bonhomme F, Edwards SV, Wakeland EK. Prevalence and evolutionary origins of autoimmune susceptibility alleles in natural mouse populations. Genes and immunity. 2008;9:61–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsui Y, Shibano K, Kashiwagi H, Yamakawa-Kobayashi K, Inoko H, Staunton DE, Thorley-Lawson DA. Characterization of genomic polymorphism of an activation-associated antigen, Blast-1. Immunogenetics. 1990;31:188–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00211554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.C. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Network-based multiple sclerosis patway analysis with GWAS data from 15,000 cases and 30,000 controls. American journal of human genetics. 2013;92:854–865. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith GM, Biggs J, Norris B, Anderson-Stewart P, Ward R. Detection of a soluble form of the leukocyte surface antigen CD48 in plasma and its elevation in patients with lymphoid leukemias and arthritis. Journal of clinical immunology. 1997;17:502–509. doi: 10.1023/a:1027327912204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Low MG, Saltiel AR. Structural and functional roles of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol in membranes. Science. 1988;239:268–275. doi: 10.1126/science.3276003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Metz CN, Brunner G, Choi-Muira NH, Nguyen H, Gabrilove J, Caras IW, Altszuler N, Rifkin DB, Wilson EL, Davitz MA. Release of GPI-anchored membrane proteins by a cell-associated GPI-specific phospholipase D. The EMBO journal. 1994;13:1741–1751. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thorley-Lawson DA, Schooley RT, Bhan AK, Nadler LM. Epstein-Barr virus superinduces a new human B cell differentiation antigen (B-LAST 1) expressed on transformed lymphoblasts. Cell. 1982;30:415–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Munitz A, Bachelet I, Finkelman FD, Rothenberg ME, Levi-Schaffer F. CD48 is critically involved in allergic eosinophilic airway inflammation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;175:911–918. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-695OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elishmereni M, Fyhrquist N, Singh Gangwar R, Lehtimaki S, Alenius H, Levi-Schaffer F. Complex 2B4 regulation of mast cells and eosinophils in murine allergic inflammation. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2014;134:2928–2937. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elishmereni M, Levi-Schaffer F. CD48: A co-stimulatory receptor of immunity. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2011;43:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heng TS, Painter MW, Immunological Genome Project C. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nature immunology. 2008;9:1091–1094. doi: 10.1038/ni1008-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katsuura M, Shimizu Y, Akiba K, Kanazawa C, Mitsui T, Sendo D, Kawakami T, Hayasaka K, Yokoyama S. CD48 expression on leukocytes in infectious diseases: flow cytometric analysis of surface antigen. Acta paediatrica Japonica; Overseas edition. 1998;40:580–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1998.tb01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larochelle A, Savona M, Wiggins M, Anderson S, Ichwan B, Keyvanfar K, Morrison SJ, Dunbar CE. Human and rhesus macaque hematopoietic stem cells cannot be purified based only on SLAM family markers. Blood. 2011;117:1550–1554. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-212803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tissot C, Rebouissou C, Klein B, Mechti N. Both human alpha/beta and gamma interferons upregulate the expression of CD48 cell surface molecules. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 1997;17:17–26. doi: 10.1089/jir.1997.17.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Munitz A, Bachelet I, Eliashar R, Khodoun M, Finkelman FD, Rothenberg ME, Levi-Schaffer F. CD48 is an allergen and IL-3-induced activation molecule on eosinophils. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:77–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rocha-de-Souza CM, Berent-Maoz B, Mankuta D, Moses AE, Levi-Schaffer F. Human mast cell activation by Staphylococcus aureus: interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha release and the role of Toll-like receptor 2 and CD48 molecules. Infection and immunity. 2008;76:4489–4497. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00270-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kis-Toth K, Tsokos GC. Engagement of SLAMF2/CD48 prolongs the time frame of effective T cell activation by supporting mature dendritic cell survival. Journal of immunology. 2014;192:4436–4442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zarama A, Perez-Carmona N, Farre D, Tomic A, Borst EM, Messerle M, Jonjic S, Engel P, Angulo A. Cytomegalovirus m154 hinders CD48 cell-surface expression and promotes viral escape from host natural killer cell control. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1004000. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perez-Carmona N, Farre D, Martinez-Vicente P, Terhorst C, Engel P, Angulo A. Signaling Lymphocytic Activation Molecule Family Receptor Homologs in New World Monkey Cytomegaloviruses. Journal of virology. 2015;89:11323–11336. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01296-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hosen N, Ichihara H, Mugitani A, Aoyama Y, Fukuda Y, Kishida S, Matsuoka Y, Nakajima H, Kawakami M, Yamagami T, Fuji S, Tamaki H, Nakao T, Nishida S, Tsuboi A, Iida S, Hino M, Oka Y, Oji Y, Sugiyama H. CD48 as a novel molecular target for antibody therapy in multiple myeloma. British journal of haematology. 2012;156:213–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shin JS, Gao Z, Abraham SN. Involvement of cellular caveolae in bacterial entry into mast cells. Science. 2000;289:785–788. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brown MH, Boles K, van der Merwe PA, Kumar V, Mathew PA, Barclay AN. 2B4, the natural killer and T cell immunoglobulin superfamily surface protein, is a ligand for CD48. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:2083–2090. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arulanandam AR, Moingeon P, Concino MF, Recny MA, Kato K, Yagita H, Koyasu S, Reinherz EL. A soluble multimeric recombinant CD2 protein identifies CD48 as a low affinity ligand for human CD2: divergence of CD2 ligands during the evolution of humans and mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1993;177:1439–1450. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dustin ML, Sanders ME, Shaw S, Springer TA. Purified lymphocyte function-associated antigen 3 binds to CD2 and mediates T lymphocyte adhesion. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1987;165:677–692. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van der Merwe PA, Barclay AN, Mason DW, Davies EA, Morgan BP, Tone M, Krishnam AK, Ianelli C, Davis SJ. Human cell-adhesion molecule CD2 binds CD58 (LFA-3) with a very low affinity and an extremely fast dissociation rate but does not bind CD48 or CD59. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10149–10160. doi: 10.1021/bi00199a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yagita H, Nakamura T, Karasuyama H, Okumura K. Monoclonal antibodies specific for murine CD2 reveal its presence on B as well as T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:645–649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Howard FD, Ledbetter JA, Wong J, Bieber CP, Stinson EB, Herzenberg LA. A human T lymphocyte differentiation marker defined by monoclonal antibodies that block E-rosette formation. Journal of immunology. 1981;126:2117–2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Crawford K, Gabuzda D, Pantazopoulos V, Xu J, Clement C, Reinherz E, Alper CA. Circulating CD2+ monocytes are dendritic cells. Journal of immunology. 1999;163:5920–5928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schuhmachers G, Ariizumi K, Mathew PA, Bennett M, Kumar V, Takashima A. 2B4, a new member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, is expressed on murine dendritic epidermal T cells and plays a functional role in their killing of skin tumors. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1995;105:592–596. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12323533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kubota K. A structurally variant form of the 2B4 antigen is expressed on the cell surface of mouse mast cells. Microbiology and immunology. 2002;46:589–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Elishmereni M, Bachelet I, Nissim Ben-Efraim AH, Mankuta D, Levi-Schaffer F. Interacting mast cells and eosinophils acquire an enhanced activation state in vitro. Allergy. 2013;68:171–179. doi: 10.1111/all.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Georgoudaki AM, Khodabandeh S, Puiac S, Persson CM, Larsson MK, Lind M, Hammarfjord O, Nabatti TH, Wallin RP, Yrlid U, Rhen M, Kumar V, Chambers BJ. CD244 is expressed on dendritic cells and regulates their functions. Immunology and cell biology. 2015;93:581–590. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Romero X, Benitez D, March S, Vilella R, Miralpeix M, Engel P. Differential expression of SAP and EAT-2-binding leukocyte cell-surface molecules CD84, CD150 (SLAM), CD229 (Ly9) and CD244 (2B4) Tissue antigens. 2004;64:132–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mathew PA, Garni-Wagner BA, Land K, Takashima A, Stoneman E, Bennett M, Kumar V. Cloning and characterization of the 2B4 gene encoding a molecule associated with non-MHC-restricted killing mediated by activated natural killer cells and T cells. Journal of immunology. 1993;151:5328–5337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith ME, Thomas JA. Cellular expression of lymphocyte function associated antigens and the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in normal tissue. Journal of clinical pathology. 1990;43:893–900. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.11.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaplan AJ, Chavin KD, Yagita H, Sandrin MS, Qin LH, Lin J, Lindenmayer G, Bromberg JS. Production and characterization of soluble and transmembrane murine CD2. Demonstration that CD48 is a ligand for CD2 and that CD48 adhesion is regulated by CD2. Journal of immunology. 1993;151:4022–4032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stefanova I, Horejsi V. Association of the CD59 and CD55 cell surface glycoproteins with other membrane molecules. Journal of immunology. 1991;147:1587–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Harder T, Simons K. Caveolae, DIGs, and the dynamics of sphingolipid-cholesterol microdomains. Current opinion in cell biology. 1997;9:534–542. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stefanova I, Horejsi V, Ansotegui IJ, Knapp W, Stockinger H. GPI-anchored cell-surface molecules complexed to protein tyrosine kinases. Science. 1991;254:1016–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1719635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moran M, Miceli MC. Engagement of GPI-linked CD48 contributes to TCR signals and cytoskeletal reorganization: a role for lipid rafts in T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;9:787–796. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stulnig TM, Berger M, Sigmund T, Stockinger H, Horejsi V, Waldhausl W. Signal transduction via glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in T cells is inhibited by lowering cellular cholesterol. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:19242–19247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patel VP, Moran M, Low TA, Miceli MC. A molecular framework for two-step T cell signaling: Lck Src homology 3 mutations discriminate distinctly regulated lipid raft reorganization events. Journal of immunology. 2001;166:754–764. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Drbal K, Moertelmaier M, Holzhauser C, Muhammad A, Fuertbauer E, Howorka S, Hinterberger M, Stockinger H, Schutz GJ. Single-molecule microscopy reveals heterogeneous dynamics of lipid raft components upon TCR engagement. International immunology. 2007;19:675–684. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Muhammad A, Schiller HB, Forster F, Eckerstorfer P, Geyeregger R, Leksa V, Zlabinger GJ, Sibilia M, Sonnleitner A, Paster W, Stockinger H. Sequential cooperation of CD2 and CD48 in the buildup of the early TCR signalosome. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:7672–7680. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chavin KD, Qin L, Lin J, Woodward J, Baliga P, Kato K, Yagita H, Bromberg JS. Anti-CD48 (murine CD2 ligand) mAbs suppress cell mediated immunity in vivo. International immunology. 1994;6:701–709. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Musgrave BL, Watson CL, Hoskin DW. CD2-CD48 interactions promote cytotoxic T lymphocyte induction and function: anti-CD2 and anti-CD48 antibodies impair cytokine synthesis, proliferation, target recognition/adhesion, and cytotoxicity. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2003;23:67–81. doi: 10.1089/107999003321455462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Musgrave BL, Watson CL, Haeryfar SM, Barnes CA, Hoskin DW. CD2-CD48 interactions promote interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma synthesis by stabilizing cytokine mRNA. Cellular immunology. 2004;229:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O'Keeffe MS, Song JH, Liao G, De Calisto J, Halibozek PJ, Mora JR, Bhan AK, Wang N, Reinecker HC, Terhorst C. SLAMF4 Is a Negative Regulator of Expansion of Cytotoxic Intraepithelial CD8+ T Cells That Maintains Homeostasis in the Small Intestine. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:991–1001. e1004. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Blackburn SD, Shin H, Haining WN, Zou T, Workman CJ, Polley A, Betts MR, Freeman GJ, Vignali DA, Wherry EJ. Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nature immunology. 2009;10:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.West EE, Youngblood B, Tan WG, Jin HT, Araki K, Alexe G, Konieczny BT, Calpe S, Freeman GJ, Terhorst C, Haining WN, Ahmed R. Tight regulation of memory CD8(+) T cells limits their effectiveness during sustained high viral load. Immunity. 2011;35:285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]