Highlight

The circadian period of the Arabidopsis thaliana leaf shortens with age. TOC1 may be a critical signalling component linking the endogenous clock to leaf ageing pathways.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, circadian clock, day length, leaf age, plant life history, TOC1.

Abstract

As most organisms age, their appearance, physiology, and behaviour alters as part of a life history strategy that maximizes their fitness over their lifetime. The passage of time is measured by organisms and is used to modulate these age-related changes. Organisms have an endogenous time measurement system called the circadian clock. This endogenous clock regulates many physiological responses throughout the life history of organisms to enhance their fitness. However, little is known about the relation between ageing and the circadian clock in plants. Here, we investigate the association of leaf ageing with circadian rhythm changes to better understand the regulation of life-history strategy in Arabidopsis. The circadian periods of clock output genes were approximately 1h shorter in older leaves than younger leaves. The periods of the core clock genes were also consistently shorter in older leaves, indicating an effect of ageing on regulation of the circadian period. Shortening of the circadian period with leaf age occurred faster in plants grown under a long photoperiod compared with a short photoperiod. We screened for a regulatory gene that links ageing and the circadian clock among multiple clock gene mutants. Only mutants for the clock oscillator TOC1 did not show a shortened circadian period during leaf ageing, suggesting that TOC1 may link age to changes in the circadian clock period. Our findings suggest that age-related information is incorporated into the regulation of the circadian period and that TOC1 is necessary for this integrative process.

Introduction

Almost all organisms undergo morphological and physiological changes as they age. Organisms possess signalling pathways that measure the passage of time and modulate the sequence of developmental change as part of a life history strategy to enhance fitness (Rougvie, 2001; Baurle and Dean, 2006). Ageing processes are genetically programmed in almost all higher organisms, from humans to plants (Lim et al., 2007; Mitteldorf and Pepper, 2007). These organisms not only sense endogenous and exogenous signals for their survival but also predict future challenges, such as seasonal changes in climate and photoperiod. Thus, most multicellular organisms have evolved biological clocks consisting of multiple genes organized in feedback loops to adjust gene expression patterns and physiological processes to seasonal/environmental conditions.

The circadian clock is a part of the endogenous time measurement system in both plants and animals (Dunlap, 1999; Song et al., 2015). Circadian clocks sense changes in environmental stimuli, such as light and temperature fluctuations, that follow day−night cycles, and can be entrained to generate internal rhythms of approximately 24h that are maintained independently of external stimuli (Millar, 2004; Harmer, 2009). The Arabidopsis thaliana circadian system consists of two major interconnected feedback loops, the morning and evening loops (Harmer, 2009; Pokhilko et al., 2010; Pokhilko et al., 2012). The morning loop includes the genes CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1), LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY), PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR (PRR) 7, and PRR9, all of which show a peak of mRNA expression levels in the morning (Farre et al., 2005; Mizuno and Nakamichi, 2005; Zeilinger et al., 2006; Nakamichi et al., 2010). The evening loop includes TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION 1 (TOC1), GIGANTEA (GI), EARLY FLOWERING (ELF) 3, ELF4, and LUX ARRYTHMO (LUX), all of which show highest expression in the evening and are transcriptionally or translationally linked to the morning loop (Fowler et al., 1999; Park et al., 1999; McWatters et al., 2000; Strayer et al., 2000; Hazen et al., 2005; Kolmos et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013). The orchestrated action of the oscillator components leads to the rhythmic behaviour of circadian outputs (Schaffer et al., 1998; Wang and Tobin, 1998; Park et al., 1999; Strayer et al., 2000; Kolmos et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2013). The endogenous circadian clock of plants regulates many aspects of plant development over the life cycle, including chloroplast movement, stomatal opening, seedling growth, leaf movement, petal opening, and flowering (Nozue et al., 2007; Sawa et al., 2007; Haydon et al., 2013). In contrast to the highly integrated circadian networks in mammals, plant rhythms appear to be less tightly coupled among cells, tissues, and organs (Thain et al., 2002). This feature allows the individual plant organs to entrain to environmental signals independently (Thain et al., 2000). Also, the same tissues at different locations within a plant (e.g., leaves) can individually modulate circadian periodicity according to unique conditions such as sun exposure (Thain et al., 2000). However, the recent finding that a vascular clock can regulate flowering time suggests that at least one of the tissue-specific clocks in the plant can affect other physiological responses (Endo et al., 2014). Further, the circadian clock in the shoot apex can function similarly to the animal master clock of the suprachiasmatic nucleus to synchronize the root circadian rhythm (Takahashi et al., 2015).

Like other plant organs, many morphological and physiological changes occur in the leaf. Rosette leaves emerge from leaf primordia of the shoot apical meristem, expand laterally and distally, and differentiate with age (Efroni et al., 2008; Bar and Ori, 2014). Many vital functions of plants take place in the leaves, such as photosynthesis, photorespiration, and transpiration. Importantly, leaves act as a sink organ for storing organic compounds during growth and maturation. Flower-inducing hormone, so called florigen, is also synthesized in leaves in response to environmental stimuli such as photoperiod and temperature, and translocates into the shoot apical meristem (Tsukaya, 2013). Then, leaves become active source organs to transfer carbon material into the seeds before eventual senescence.

In this study, we examined the relation between leaf ageing and the circadian clock in Arabidopsis leaves. We found that the circadian period differed among leaves within a single plant. We observed the circadian period shortening with leaf ageing by measuring the promoter activity and the expression of circadian clock genes. Changes in the circadian period with leaf age occurred faster in plants grown under long day conditions than under short day conditions. Further, TOC1 gene mutants showed no such age-dependent changes, suggesting that the circadian rhythm is regulated by age through the TOC1, clock oscillator.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

To monitor changes in clock gene expression with age and identify leaf age-dependent circadian regulators, we generated several transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana lines expressing the firefly luciferase gene under control of the clock responsive COLD CIRCADIAN RHYTHM AND RNA BINDING 2 (CCR2), and CCA1 promoters. Before the cross, cca1-11 (on the Ws background) (Gould et al., 2006) and toc1-1 (on C24) (Millar et al., 1995) were backcrossed three times with Col-0 wild type. We then crossed CCR2p::LUC with cca1-11, toc1-1, and toc1-101 mutants (Kikis et al., 2005) and CCA1p::LUC with lhy-20 mutants (Michael et al., 2003) to measure circadian rhythmicity. CCA1p::LUC was introduced into the prr7-3 and prr9-1 mutants by Agrobacterium transformation.

Plant growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana was grown in an environmentally controlled growth room at 22 °C under a 12-h light–12-h dark cycle (12L/12D), a 16-h light–8-h dark cycle (16L/8D; longer photoperiod), or an 8-h light–16-h dark cycle (8L/16D; shorter photoperiod) using 100 μmol m−2 s−1 white light. The plants were then transferred to continuous white light at the same light intensity to measure rhythmic changes in luciferase emission from transgenic leaves. All experiments except that shown in Fig. 1 were performed using the third and fourth rosette leaves.

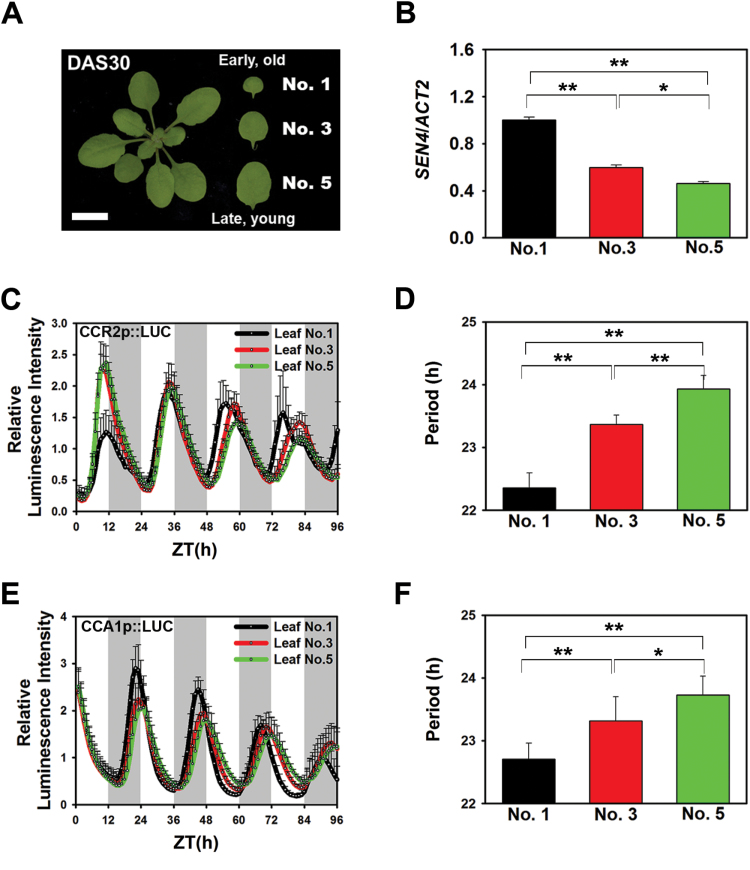

Fig. 1.

Early emerged (older) Arabidopsis leaves show a shorter circadian period than late emerged (younger) leaves.

(A) A wild type Arabidopsis thaliana rosette leaf at 30 days after sowing (DAS) showing early emerged (older) and later emerged (younger) leaves. Scale bar: 1cm. (B) Expression of the age-induced marker gene SEN4 at the indicated leaf number. The first, third, and fifth leaf samples were harvested at zeitgeber (ZT) 4. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) of biological triplicates. (C, E) Time course of bioluminescence levels in plants expressing CCR2p::LUC (C) or CCA1p::LUC (E). Luminescence intensities were measured every hour under continuous light (LL) conditions starting at the leaf number indicated. (D, F) Circadian period estimates of the activities of CCR2 (D) and CCA1 (F) promoters. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from eight leaves. The single (P<0.05) and double (P<0.01) asterisks indicate significant difference (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test for pairwise comparisons). White bars indicate subjective day, and gray shading indicates subjective night. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Measurement of mRNA expression levels

Total mRNA was extracted from the leaves using WelPrep (Welgene, Daegu, Korea). Contaminating DNA was removed by digestion with DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). For each sample, 0.75 μg of total mRNA was reverse-transcribed using ImProm II reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The quantity of each transcript in a sample was measured using real-time PCR with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) and an ABI 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primers used in this study and their sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online.

Luminescence assay

Transgenic plants expressing luciferase under the control of the CCR2 and CCA1 promoters (Strayer et al., 2000) were used in this assay. The third and fourth rosette leaves were excised at their petioles from transgenic plants and transferred to 24-well microplates containing 500 µM luciferin (SYNCHEM, Felsberg/Altenburg, Germany). Luminescence images were acquired every hour for 4 days and luminescence intensities from each leaf were imported into the Biological Rhythms Analysis Software System (BRASS) (Southern and Millar, 2005). Circadian period lengths were calculated using the FFT-NLLS suite (Plautz et al., 1997).

Results

Circadian period heterogeneity of leaves within a single Arabidopsis plant

Arabidopsis leaves are sequentially generated as the plant ages. A leaf that emerges earlier is older than a leaf that emerges later; thus, leaves of various ages occur in a single plant (Zentgraf et al., 2004). We first analysed whether circadian rhythms are synchronized among leaves within a plant. The circadian rhythms of the first, third, and fifth emerged leaves were examined at 30 days after sowing (DAS) (Fig. 1A). Expression of the age-associated marker SENESCENSE 4 (SEN4) was higher in the earlier emerged leaf (leaf number 1) than in the later emerged leaf (leaf number 5), which is consistent with a previous report (Fig. 1B) (Zentgraf et al., 2004). Cyclic activities of the CCR2 (clock output) and CCA1 (core oscillator) gene promoters were measured at 30 DAS in the leaves of transgenic plants expressing CCR2p::Luciferase (LUC) and CCA1p::LUC, respectively (Strayer et al., 2000). Both transgenic plants were entrained under a 12L/12D cycle. Then, leaves were transferred to continuous light (LL) conditions to examine the endogenous circadian rhythm. The rhythmic expression levels were robust in both transgenic plants and varied with the leaf number. Specifically, the circadian periods of these reporters were shorter in early-emerged leaves, approximately 22.6h in the first emerged leaves versus nearly 24h in the fifth emerged leaves (Fig. 1D, F). Thus, the circadian clock period length varies among leaves of a single plant according to time of leaf emergence. This heterogeneity is consistent with previous reports that plant circadian rhythms are often uncoupled among cells and tissues (Wenden et al., 2012; Endo et al., 2014). Interestingly, this also implies a possibility that the circadian rhythm might be correlated with leaf age. Thus, we hypothesized that there is an age-dependent circadian regulation in Arabidopsis leaves. To test this hypothesis, we focused on the third and fourth leaves of an Arabidopsis rosette in order to be certain of the leaf age and to avoid mixing leaf ages within a single plant (Zentgraf et al., 2004).

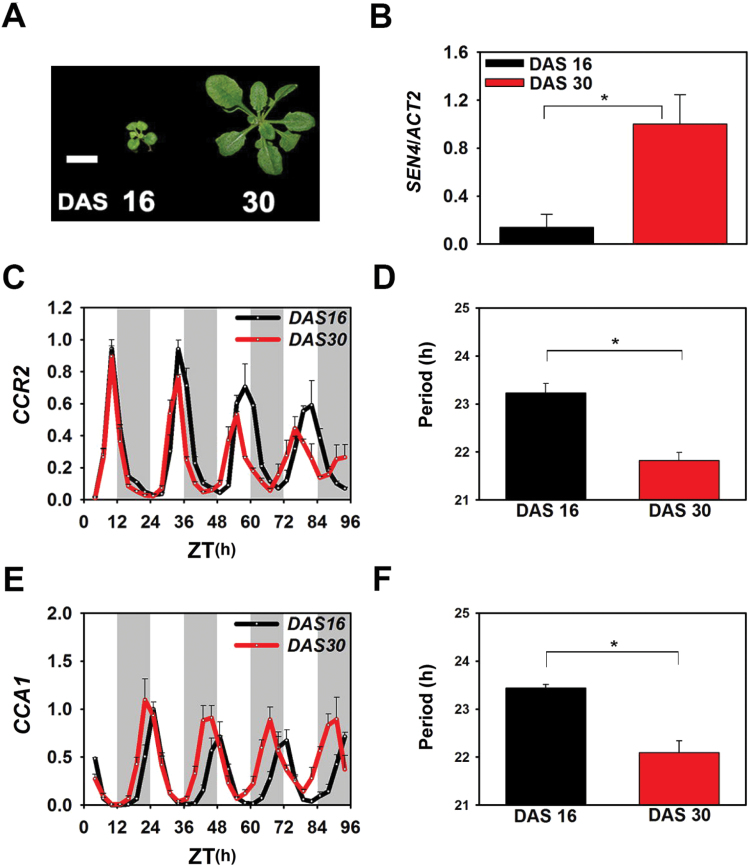

The circadian period is shortened with leaf ageing

To address how circadian rhythms respond chronologically, changes in the circadian rhythm were examined as the plant leaf ages. Experiments were performed before flowering to avoid the possible confounding effects of flowering (Hayama and Coupland, 2003). We harvested the third and fourth leaves from plants at 16 and 30 DAS for 4 days under free-running cycles entrained by a 12L/12D cycle (Fig. 2A). To objectively measure leaf age, we introduced SEN4 as a molecular marker and measured SEN4 mRNA expression in 16 and 30 DAS at 4h after lights on [zeitgeber (ZT) 4] (Oh et al., 1996; Gan and Amasino, 1997). SEN4 expression in leaves increased approximately 10-fold from 16 to 30 DAS, indicating that the leaves under investigation were aged (Fig. 2B). We measured the CCR2 gene at these stages and found that the cycling of CCR2 gene expression was robust at both 16 and 30 DAS, but that the circadian period was significantly shorter at 30 DAS compared with 16 DAS (Fig. 2C, D). Consistent with a shorter circadian period with age, the phases of the circadian peak were advanced at 30 DAS relative to 16 DAS for the third and fourth emerged leaves (Fig. 2C, D).

Fig. 2.

Circadian period is getting shorter with Arabidopsis leaf age.

(A) Images show WT plants at the indicated leaf ages. Scale bar: 1cm. (B) Expression of the age-induced marker gene SEN4 at the indicated leaf ages. Leaf samples were collected at ZT 4. (C) Expression of CCR2, a clock output gene, under LL. (E) Expression of CCA1, a clock oscillator gene, under LL. (D, F) Circadian period estimates for CCR2 (D) and CCA1 (F). Data are presented as the mean±SE of biological triplicates. The third and fourth leaf samples were collected for this analysis. mRNA levels were measured using quantitative RT-PCR and then normalized to ACT2 expression. The asterisk indicates that the period values differ significantly (P<0.05) from young leaves (Tukey’s HSD test after one-way ANOVA). White bars indicate subjective day, and gray shading indicates subjective night. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Next, we examined whether the shorter period of circadian output genes such as CCR2 in aged leaves results from parallel changes in the central oscillator by measuring the cyclic expression of nine core oscillator genes (Supplementary Fig. S1A). All monitored genes showed significantly shortened circadian periods in aged leaves compared with young leaves (~1h difference), thus closely recapitulating the change in cycling behaviour of CCR2 expression with age (Fig. 2F and Supplementary Fig. S1B–I). We also tested whether the phase advance of expression of the core oscillator genes can be seen under diurnal conditions. However, the phases of the oscillator genes were not significantly altered from young to aged leaves (Supplementary Fig. S2). These parallel changes in circadian periods of central clock genes under free-running circadian cycles suggest age-dependent changes in multiple periodic physiological processes under control of the circadian core oscillators.

We further confirmed this circadian period shortening with leaf age using transgenic plants carrying CCR2p::LUC and CCA1p::LUC (Supplementary Fig. S3). Both transgenic plants were entrained under 12L/12D cycles, and the rhythmic expression levels of these reporter genes were measured in detached third and fourth leaves under continuous light. Similar to CCR2 and CCA1 genes in attached leaves, the circadian periods of CCR2 and CCA1 promoter activity were significantly shorter at 30 DAS (again by approximately 1h) compared with 16 DAS (Supplementary Fig. S3). Collectively, these results suggest that the circadian periods of both core oscillator and clock output genes progressively decrease with leaf age.

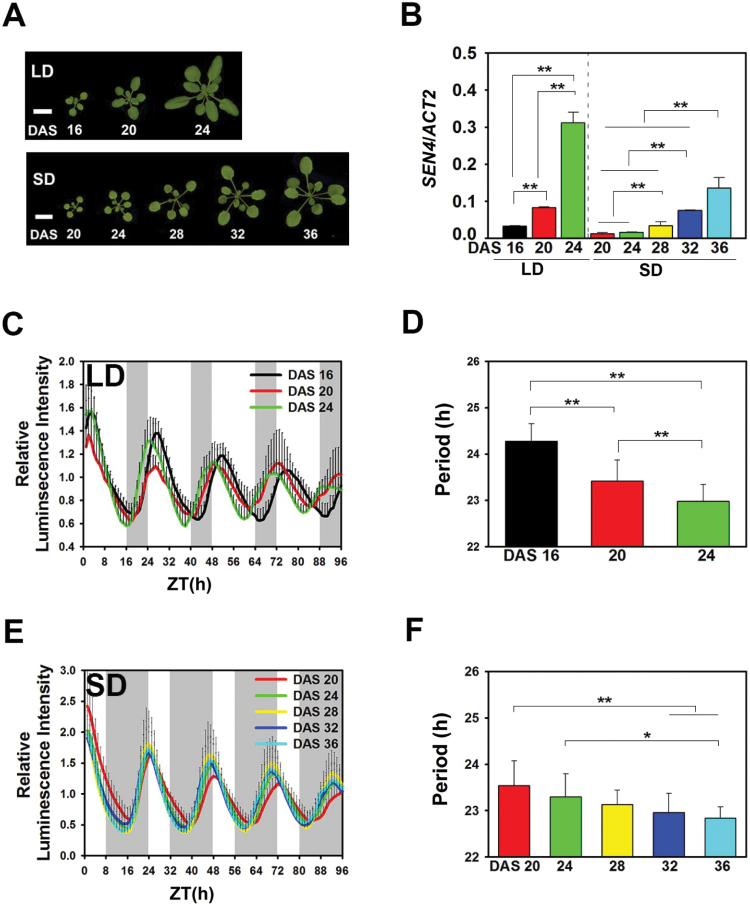

The age-dependent change in circadian period is accelerated under a longer photoperiod

Arabidopsis thaliana is a facultative long-day plant, indicating that the transition from the vegetative to reproductive stage is faster under a long photoperiod than under a short photoperiod (Corbesier et al., 1996). Sensing the external photoperiod is one mechanism through which the endogenous circadian clock controls flowering in Arabidopsis. Thus, we hypothesized that the rate of circadian period shortening during leaf ageing would vary with day length. To test this hypothesis, the cyclic luminescence activity of the CCA1 promoter was measured in plants grown under short day (SD) (8L/16D) and long day (LD) (16L/8D) conditions. Leaves were collected before flowering every 4 days, starting at 20 DAS for plants grown under SD conditions and at 16 DAS for plants grown under LD conditions (Fig. 3A). SEN4 expression progressively increased under both photoperiod conditions, but the rate of increase was higher under the LD than under SD conditions, indicating that leaf ageing is faster under a long photoperiod compared with a short photoperiod (Fig. 3B). The circadian period gradually shortened with leaf age under both conditions (Fig. 3D, F). The circadian period under SD was significantly shortened at 32 and 36 DAS compared with the period at 20 DAS (Fig. 3F). The period shortening under SD took much longer than under LD, which correlates with the milder increase of SEN4 expression under SD compared with LD (Fig. 3B). This result indicates that leaf ageing differs with the day length and that this correlates to the shortening of the circadian period with leaf ageing.

Fig. 3.

Arabidopsis leaves show accelerated circadian period shortening under a long photoperiod

. (A) Images of plants grown under long and short photoperiod conditions at the indicated age. Scale bar: 1cm. (B) Expression of the age-induced marker gene SEN4 at the indicated leaf ages. The third and fourth leaf samples were collected at ZT 4. Data are presented as the mean±SE of biological triplicates. (C, E) CCA1 promoter activity was measured by monitoring the luminescence intensity from leaves of transgenic plants expressing luciferase under the control of the CCA1 promoter. Luminescence intensities were measured every hour at the indicated leaf age under LL conditions. (D, F) Circadian period estimates for CCA1p::LUC from data shown in (C, E). Data are presented as the mean±SD from 20 leaves. The single (P<0.05) and double (P<0.01) asterisks indicate significant difference (Tukey’s HSD test after one-way ANOVA). (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

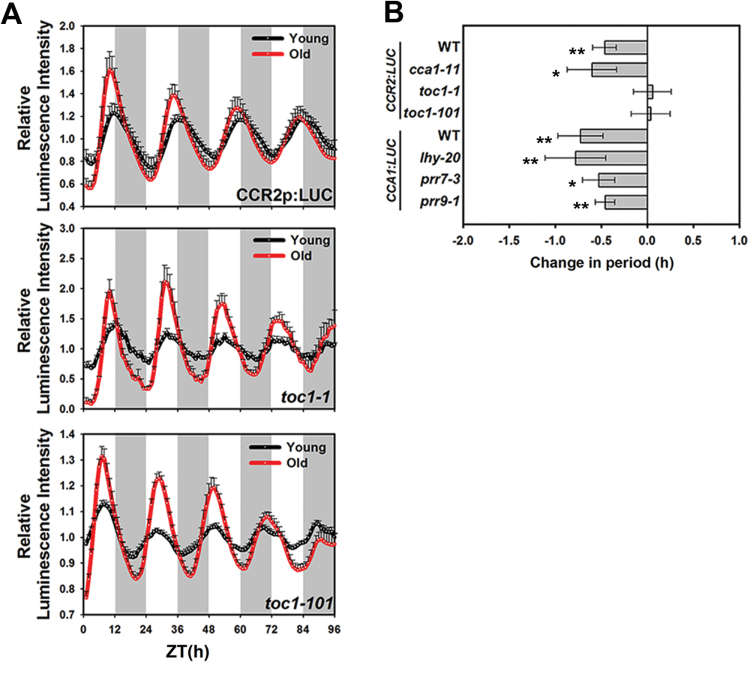

TOC1 is involved in age-dependent changes in the circadian rhythm

Leaf age affects the endogenous clock at the level of the core oscillator as well as at the level of clock output genes (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1), suggesting that a component of the core oscillator acts to link leaf age to downstream effects on clock outputs. We screened several clock mutants that have defects in clock regulation during leaf ageing. Leaves from mutant and wild type (WT) plants grown under 12L/12D were collected at 18 and 28 DAS and the clock activities measured under continuous light. Consistent with the previous results, leaf age significantly shortened the circadian periods of CCR2p::LUC and CCA1p::LUC (by approximately 30min) in WT leaves (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the circadian periods significantly shortened with leaf age in cca1-11, lhy-20, prr7-3, and prr9-1 mutants, and the differences in period between young and old leaves were statistically indistinguishable from WT plants (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S4). Interestingly, the circadian period in toc1 mutants (toc1-1 and toc1-101) did not shorten with leaf ageing in contrast to other clock mutants that we tested (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S4) and the circadian phase in toc1 mutants was not advanced with leaf age (Fig. 4A). This finding implicates TOC1 as a key regulator linking leaf ageing with changes in the endogenous circadian clock period.

Fig. 4.

TOC1 is a critical clock oscillator in the age-interacting clock network.

(A) CCR2 promoter activity was measured by monitoring luminescence intensity from the leaves of transgenic plants expressing luciferase under the control of the CCR2 promoter. Luminescence intensities were measured every hour under LL conditions. White bars indicate day, and grey bars indicate night. (B) Change in the circadian period of CCR2p::LUC and CCA1p::LUC activity in several clock mutants. Grey bars indicate the circadian period change between 18 DAS and 28 DAS. Data are presented as the mean±SD of about 16 third and fourth leaves. The single (P<0.05) and double (P<0.01) asterisks indicate significant difference from the period of young leaves (Tukey’s HSD test after one-way ANOVA). (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Discussion

We found that each leaf in an Arabidopsis thaliana plant has a different circadian period depending on its age. The older, early emerged leaves of the Arabidopsis rosette had a shorter circadian period than the younger, later emerged leaves (Fig. 1). This finding indicates that the circadian rhythm is not synchronized within a plant. In the mammalian circadian system, the suprachiasmatic nucleus generates a ‘master’ circadian rhythm that modulates peripheral clocks to synchronize whole-body circadian rhythms (Reppert and Weaver, 2002). In contrast, plants have an independent autonomous circadian system at the cellular and tissue levels (Thain et al., 2000), which could allow differential responses to similar environmental conditions. This suggests that the circadian rhythm in a leaf is spatially distinguishable, and thus, it might individually respond to age (Fig. 1).

Changes in the cyclic behaviour of the core circadian system regulates numerous developmental outputs throughout the plant life cycle, including photoperiodic control of seedling growth in young stages and photoperiodic control of flowering in mature stages (Nozue et al., 2007; Sawa et al., 2007; de Montaigu et al., 2010; McWatters and Devlin, 2011; Kim et al., 2012). In Arabidopsis, as leaves age, a globally orchestrated change was observed in the circadian periods of core oscillators (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Changes in the rhythmic behaviour of even a single component of the core circadian oscillator may affect diverse aspects of plant physiology (Schaffer et al., 1998; Wang and Tobin, 1998; Park et al., 1999; Strayer et al., 2000; Doyle et al., 2002). It is thus conceivable that age-dependent changes in the circadian rhythm provide a regulatory means of linking age-related information to downstream developmental events.

Many physiological processes are dependent on day length, such as flowering and leaf senescence (Corbesier et al., 1996; Nooden et al., 1996). Arabidopsis developmental processes are induced more rapidly under long day than under short day conditions. Our results suggest that the shortening of the circadian period is age dependent and responds to the photoperiod. The circadian period shortens rapidly with leaf age under long photoperiod compared with short photoperiod conditions (Fig. 3). This finding suggests that the circadian clock and ageing and environmental signals work interactively in Arabidopsis developmental processes.

TOC1 is one of the clock oscillators in the Arabidopsis circadian network. TOC1-deficient mutants exhibit a short-period phenotype in the seedling stage and an early flowering phenotype in the mature stage (Somers et al., 1998; Strayer et al., 2000). TOC1 also functions in photomorphogenic processes (Mas et al., 2003). We found that leaf circadian periods in toc1 mutants (toc1-1 and toc1-101) were insensitive to leaf ageing (Fig. 4). TOC1 is closely associated with the abscisic acid (ABA) signalling pathway. ABA is a phytohormone that acts to coordinate stress responses to various stressor combinations. In addition, ABA is known to increase with leaf age and to regulate some features of leaf development (Breeze et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011). ABA induces TOC1 mRNA expression through ABA BINDING PROTEIN (ABAR) (Legnaioli et al., 2009). Reciprocally, the circadian clock affects the oscillations of several ABA signalling genes, including ABI1, RCAR1, and ABF3 (Seung et al., 2012). However, ABA treatment of seedlings lengthens the circadian period under continuous light conditions (Hanano et al., 2006). The functional interactions between ABA signalling and TOC1 during leaf ageing are still largely unknown. However, given that ABA does regulate TOC1 expression, it is a potential candidate age-related stimulus affecting the circadian clock through TOC1.

It remains unclear how ageing is associated with changes in the circadian system, particularly whether there is indeed a causal relationship between them or if such observations arise merely from coincidence. It is not yet known how age-dependent changes in the circadian clock system and infradian developmental events such as flowering and senescence are interlinked. Our results described here may provide the first insights for understanding how leaf age and age-dependent changes in the circadian clock are incorporated into age-dependent developmental decisions.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Figure S1. The rhythmic behaviour of core clock oscillators differs between young and aged leaves.

Figure S2. The phase of the clock oscillator genes is not significantly different in young and aged leaves under diurnal condition.

Figure S3. The rhythmic behaviour of clock gene promoters differs between young and aged detached leaves.

Figure S4. Age-dependent circadian rhythms in several clock oscillator mutants.

Table S1. Oligonucleotides used for real-time PCR.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Project Code (IBS-R013-D1), Republic of Korea. We thank K. H. Suh, Y. S. Park, and B. H. Kim for their technical assistance.

References

- Bar M, Ori N. 2014. Leaf development and morphogenesis. Development 141, 4219–4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baurle I, Dean C. 2006. The timing of developmental transitions in plants. Cell 125, 655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze E, Harrison E, McHattie S, et al. 2011. High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts during Arabidopsis leaf senescence reveals a distinct chronology of processes and regulation. The Plant Cell 23, 873–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L, Gadisseur I, Silvestre G, Jacqmard A, Bernier G. 1996. Design in Arabidopsis thaliana of a synchronous system of floral induction by one long day. The Plant Journal 9, 947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Montaigu A, Toth R, Coupland G. 2010. Plant development goes like clockwork. Trends in Genetics 26, 296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle MR, Davis SJ, Bastow RM, McWatters HG, Kozma-Bognar L, Nagy F, Millar AJ, Amasino RM. 2002. The ELF4 gene controls circadian rhythms and flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 419, 74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap JC. 1999. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell 96, 271–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efroni I, Blum E, Goldshmidt A, Eshed Y. 2008. A protracted and dynamic maturation schedule underlies Arabidopsis leaf development. The Plant Cell 20, 2293–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M, Shimizu H, Nohales MA, Araki T, Kay SA. 2014. Tissue-specific clocks in Arabidopsis show asymmetric coupling. Nature 515, 419–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farre EM, Harmer SL, Harmon FG, Yanovsky MJ, Kay SA. 2005. Overlapping and distinct roles of PRR7 and PRR9 in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Current Biology 15, 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S, Lee K, Onouchi H, Samach A, Richardson K, Morris B, Coupland G, Putterill J. 1999. GIGANTEA: a circadian clock-controlled gene that regulates photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis and encodes a protein with several possible membrane-spanning domains. The EMBO Journal 18, 4679–4688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan S, Amasino RM.1997. Making sense of senescence (molecular genetic regulation and manipulation of leaf senescence). Plant Physiology 113, 313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould PD, Locke JC, Larue C, Southern MM, Davis SJ, Hanano S, Moyle R, Milich R, Putterill J, Millar AJ, Hall A. 2006. The molecular basis of temperature compensation in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. The Plant Cell 18, 1177–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanano S, Domagalska MA, Nagy F, Davis SJ. 2006. Multiple phytohormones influence distinct parameters of the plant circadian clock. Genes to Cells 11, 1381–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer SL. 2009. The circadian system in higher plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 60, 357–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayama R, Coupland G. 2003. Shedding light on the circadian clock and the photoperiodic control of flowering. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 6, 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon MJ, Hearn TJ, Bell LJ, Hannah MA, Webb AA. 2013. Metabolic regulation of circadian clocks. Seminar in Cell and Developmental Biology 24, 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen SP, Schultz TF, Pruneda-Paz JL, Borevitz JO, Ecker JR, Kay SA. 2005. LUX ARRHYTHMO encodes a Myb domain protein essential for circadian rhythms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 10387–10392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikis EA, Khanna R, Quail PH. 2005. ELF4 is a phytochrome-regulated component of a negative-feedback loop involving the central oscillator components CCA1 and LHY. The Plant Journal 44, 300–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Han S, Yeom M, Kim H, Lim J, Cha JY, Kim WY, Somers DE, Putterill J, Nam HG, Hwang D. 2013. Balanced nucleocytosolic partitioning defines a spatial network to coordinate circadian physiology in plants. Developmental Cell 26, 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Yeom M, Kim H, Lim J, Koo HJ, Hwang D, Somers D, Nam HG. 2012. GIGANTEA and EARLY FLOWERING 4 in Arabidopsis exhibit differential phase-specific genetic influences over a diurnal cycle. Molecular Plant 5, 152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmos E, Nowak M, Werner M, Fischer K, Schwarz G, Mathews S, Schoof H, Nagy F, Bujnicki JM, Davis SJ. 2009. Integrating ELF4 into the circadian system through combined structural and functional studies. HFSP Journal 3, 350–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IC, Hong SW, Whang SS, Lim PO, Nam HG, Koo JC. 2011. Age-dependent action of an ABA-inducible receptor kinase, RPK1, as a positive regulator of senescence in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant & Cell Physiology 52, 651–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legnaioli T, Cuevas J, Mas P. 2009. TOC1 functions as a molecular switch connecting the circadian clock with plant responses to drought. The EMBO Journal 28, 3745–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim PO, Kim HJ, Nam HG. 2007. Leaf senescence. Annual Review of Plant Biology 58, 115–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas P, Alabadi D, Yanovsky MJ, Oyama T, Kay SA. 2003. Dual role of TOC1 in the control of circadian and photomorphogenic responses in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 15, 223–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWatters HG, Bastow RM, Hall A, Millar AJ. 2000. The ELF3 zeitnehmer regulates light signalling to the circadian clock. Nature 408, 716–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWatters HG, Devlin PF. 2011. Timing in plants--a rhythmic arrangement. FEBS Letters 585, 1474–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael TP, Salome PA, Yu HJ, Spencer TR, Sharp EL, McPeek MA, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, McClung CR. 2003. Enhanced fitness conferred by naturally occurring variation in the circadian clock. Science 302, 1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar AJ. 2004. Input signals to the plant circadian clock. Jounal of Experimental Botany 55, 277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar AJ, Carre IA, Strayer CA, Chua NH, Kay SA. 1995. Circadian clock mutants in Arabidopsis identified by luciferase imaging. Science 267, 1161–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitteldorf J, Pepper JW. 2007. How can evolutionary theory accommodate recent empirical results on organismal senescence? Theory in Bioscience 126, 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Nakamichi N. 2005. Pseudo-Response Regulators (PRRs) or True Oscillator Components (TOCs). Plant & Cell Physiology 46, 677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamichi N, Kiba T, Henriques R, Mizuno T, Chua NH, Sakakibara H. 2010. PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORS 9, 7, and 5 are transcriptional repressors in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. The Plant Cell 22, 594–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooden LD, Hillsberg JW, Schneider MJ. 1996. Induction of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana by long days through a light-dosage effect. Physiologia Plantarum 96, 491–495. [Google Scholar]

- Nozue K, Covington MF, Duek PD, Lorrain S, Fankhauser C, Harmer SL, Maloof JN. 2007. Rhythmic growth explained by coincidence between internal and external cues. Nature 448, 358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SA, Lee SY, Chung IK, Lee CH, Nam HG. 1996. A senescence-associated gene of Arabidopsis thaliana is distinctively regulated during natural and artificially induced leaf senescence. Plant Molecular Biology 30, 739–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DH, Somers DE, Kim YS, Choy YH, Lim HK, Soh MS, Kim HJ, Kay SA, Nam HG. 1999. Control of circadian rhythms and photoperiodic flowering by the Arabidopsis GIGANTEA gene. Science 285, 1579–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plautz JD, Straume M, Stanewsky R, Jamison CF, Brandes C, Dowse HB, Hall JC, Kay SA. 1997. Quantitative analysis of Drosophila period gene transcription in living animals. Journal of Biological Rhythms 12, 204–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhilko A, Fernandez AP, Edwards KD, Southern MM, Halliday KJ, Millar AJ. 2012. The clock gene circuit in Arabidopsis includes a repressilator with additional feedback loops. Molecular Systems Biology 8, 574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhilko A, Hodge SK, Stratford K, Knox K, Edwards KD, Thomson AW, Mizuno T, Millar AJ. 2010. Data assimilation constrains new connections and components in a complex, eukaryotic circadian clock model. Molecular Systems Biology 6, 416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR. 2002. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418, 935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougvie AE. 2001. Control of developmental timing in animals. Nature Reviews. Genetics 2, 690–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa M, Nusinow DA, Kay SA, Imaizumi T. 2007. FKF1 and GIGANTEA complex formation is required for day-length measurement in Arabidopsis. Science 318, 261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer R, Ramsay N, Samach A, Corden S, Putterill J, Carre IA, Coupland G. 1998. The late elongated hypocotyl mutation of Arabidopsis disrupts circadian rhythms and the photoperiodic control of flowering. Cell 93, 1219–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung D, Risopatron JP, Jones BJ, Marc J. 2012. Circadian clock-dependent gating in ABA signalling networks. Protoplasma 249, 445–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers DE, Webb AA, Pearson M, Kay SA. 1998. The short-period mutant, toc1-1, alters circadian clock regulation of multiple outputs throughout development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 125, 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song YH, Shim JS, Kinmonth-Schultz HA, Imaizumi T. 2015. Photoperiodic flowering: time measurement mechanisms in leaves. Annual Review of Plant Biology 66, 441–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern MM, Millar AJ. 2005. Circadian genetics in the model higher plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. Methods in Enzymology 393, 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayer C, Oyama T, Schultz TF, Raman R, Somers DE, Mas P, Panda S, Kreps JA, Kay SA. 2000. Cloning of the Arabidopsis clock gene TOC1, an autoregulatory response regulator homolog. Science 289, 768–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Hirata Y, Aihara K, Mas P. 2015. A hierarchical multi-oscillator network orchestrates the Arabidopsis circadian system. Cell 163, 148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thain SC, Hall A, Millar AJ. 2000. Functional independence of circadian clocks that regulate plant gene expression. Current Biology 10, 951–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thain SC, Murtas G, Lynn JR, McGrath RB, Millar AJ. 2002. The circadian clock that controls gene expression in Arabidopsis is tissue specific. Plant Physiology 130, 102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H. 2013. Leaf development. Arabidopsis Book 11, e0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Tobin EM. 1998. Constitutive expression of the CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) gene disrupts circadian rhythms and suppresses its own expression. Cell 93, 1207–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenden B, Toner DL, Hodge SK, Grima R, Millar AJ. 2012. Spontaneous spatiotemporal waves of gene expression from biological clocks in the leaf. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 6757–6762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilinger MN, Farre EM, Taylor SR, Kay SA, Doyle FJ., 3rd 2006. A novel computational model of the circadian clock in Arabidopsis that incorporates PRR7 and PRR9. Molecular Systems Biology 2, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentgraf U, Jobst J, Kolb D, Rentsch D. 2004. Senescence-related gene expression profiles of rosette leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana: leaf age versus plant age. Plant Biology 6, 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.