Abstract

Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and ephrin ligands constitute an important cell communication system that controls development, tissue homeostasis and many pathological processes. Various Eph receptors/ephrins are present in essentially all cell types and their expression is often dysregulated by injury and disease. Thus, the 14 Eph receptors are attracting increasing attention as a major class of potential drug targets. In particular, agents that bind to the extracellular ephrin-binding pocket of these receptors show promise for medical applications. This pocket comprises a broad and shallow groove surrounded by several flexible loops, which makes peptides particularly suitable to target it with high affinity and selectivity. Accordingly, a number of peptides that bind to Eph receptors with micromolar affinity have been identified using phage display and other approaches. These peptides are generally antagonists that inhibit ephrin binding and Eph receptor/ephrin signaling, but some are agonists mimicking ephrin-induced Eph receptor activation. Importantly, some of the peptides are exquisitely selective for single Eph receptors. Most identified peptides are linear, but recently the considerable advantages of cyclic scaffolds have been recognized, particularly in light of potential optimization towards drug leads. To date, peptide improvements have yielded derivatives with low nanomolar Eph receptor binding affinity, high resistance to plasma proteases and/or long in vivo half-life, exemplifying the merits of peptides for Eph receptor targeting. Besides their modulation of Eph receptor/ephrin function, peptides can also serve to deliver conjugated imaging and therapeutic agents or various types of nanoparticles to tumors and other diseased tissues presenting target Eph receptors.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, cancer, cyclic peptide, linear peptide, neural repair, neurodegenerative diseases, protein-protein interactions

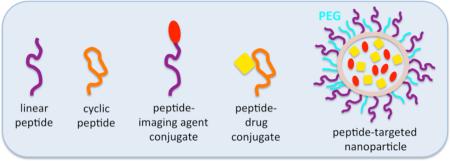

Graphical Abstract

Linear and cyclic peptides that bind to Eph receptors can be conjugated to imaging agents or drugs and incorporated into nanoparticles for targeted delivery to Eph receptor-positive diseased tissues.

INTRODUCTION

The Eph receptor tyrosine kinase system consists of 9 EphA receptors and their 5 glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked ephrin-A ligands as well as 5 EphB receptors and their 3 transmembrane ephrin-B ligands [1-4]. Eph receptor-ephrin interactions within each class (A or B) are generally promiscuous, and binding between Eph receptors and ephrins of different classes can also occur. Biologically, the Eph receptors bind ephrin ligands across sites of contact between cells (Fig. 1A), leading to clustering of Eph receptor-ephrin complexes and the generation of juxtacrine signals. These signals propagate bidirectionally, that is through both the Eph receptor and the ephrin (Fig. 1A). In addition, soluble forms of the ephrin-A ligands can be generated through proteolytic cleavage by metalloproteases and after being released they can bind to certain EphA receptors to trigger paracrine signaling. Besides these ephrin-dependent signaling mechanisms, the Eph receptors can also signal in a ligand- and kinase-independent manner [2, 3, 5]. This non-canonical signaling can result, for example, from interplay with other families of receptor tyrosine kinases or with serine/threonine kinases such as AKT. It is this variety of signaling mechanisms that enables the Eph receptor/ephrin system to regulate a wide spectrum of cellular processes including cell adhesion, movement and invasiveness, proliferation, survival, differentiation and self-renewal. Through these activities, Eph receptors and ephrins play a key role in developmental processes and adult tissue homeostasis as well as in a variety of diseases ranging from neurodegenerative disorders to pathological forms of angiogenesis and cancer [1, 3-6].

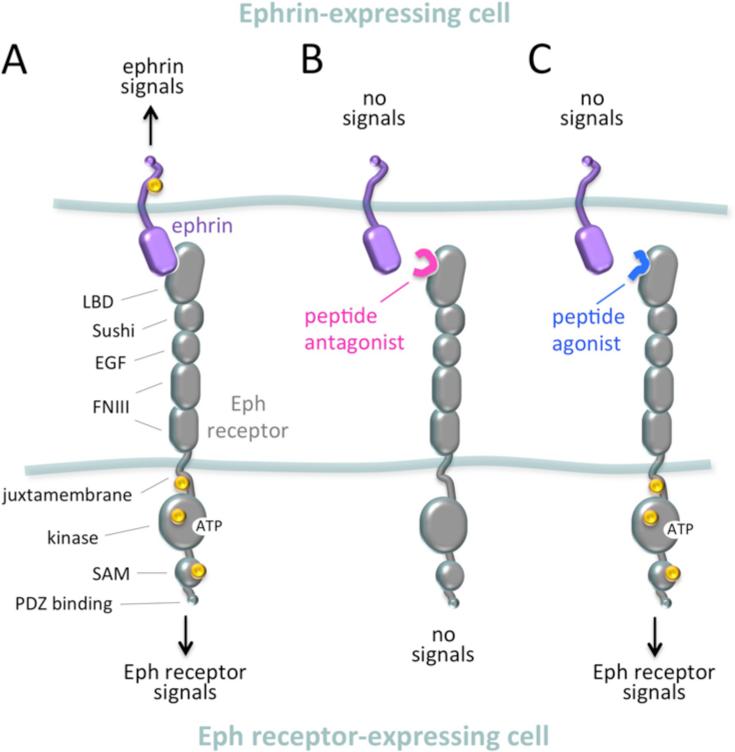

Fig. 1. Effects of peptides on Eph receptor-ephrin bidirectional signaling.

(A) Bidirectional signaling of an Eph receptor-ephrin complex assembled where an Eph receptor-expressing cell comes near an ephrin-expressing cell. Only one Eph receptor and one ephrin (of the B transmembrane class) are shown for simplicity, even though signaling typically involves clustering of multiple Eph receptor-ephrin complexes. The domains of the Eph receptor are indicated. Yellow circles represent the tyrosine phosphorylation sites involved in the signaling activities of the Eph receptor and the ephrin-B ligand. The plasma membranes of the two cells are represented by light blue lines. (B) A peptide antagonist inhibits signaling by both the Eph receptor and the ephrin. (C) A peptide agonist activates Eph receptor signaling and inhibits ephrin signaling.

These important biological activities and a frequently elevated expression in diseased tissues make Eph receptors promising targets for the development of therapies to treat a wide variety of human pathologies [3, 5, 6]. In particular, agents that selectively modulate the activity of specific Eph receptors and ephrins have the potential to be developed for clinical applications. In addition, such molecules can also serve as research tools in pharmacological loss-of-function or gain-of-function approaches to elucidate the specific biological activities of individual Eph receptor/ephrin family members and validate their potential as therapeutic targets. Various strategies to modulate Eph receptor/ephrin signal transduction have been reported. These include targeting the ATP binding pocket in the Eph receptor kinase domain with small molecule kinase inhibitors [7]. Other strategies to interfere with the activities of the Eph system involve Eph receptor/ephrin downregulation with siRNAs, miRNAs or biologics such as ligands and antibody agonists [3]. Another main approach is to directly target the ephrin-binding pocket of the Eph receptors. This can be accomplished with chemical compounds [8] or with peptides, which is the focus of this review.

Peptides cover the chemical space between small molecule drugs (with molecular weight up to 500) and biologics (typically with molecular weight above 5,000) [9]. Advantages of peptides over small molecules are that peptides (i) can bind with high affinity to protein-protein interfaces even in the absence of the highly concave pockets preferred by small molecules, (ii) are particularly effective at inhibiting protein-protein interactions due to their larger size and (iii) in general have low toxicity [9-12]. Advantages of peptides over biologics are their low immunogenicity, more efficient tissue penetration, and generally lower production costs. These factors make peptides attractive for targeting the Eph receptor ligand-binding domain (LBD). Importantly, the Eph receptor LBD is extracellular, and therefore peptides targeting this domain do not need to cross the plasma membrane, thus circumventing a major problem encountered in the use of peptides that bind to intracellular targets [13-15]. Peptides can also have some disadvantages, including their potentially poor pharmacokinetic parameters and oral bioavailability. However, advances in peptide medicinal chemistry and alternative formulations can resolve at least some of these issues, as demonstrated by the fact that peptides represent an ever increasing proportion of newly approved drugs (for example, 8% of the drugs approved by the FDA between 2009 and 2011 were peptides) [9-12].

As mentioned above, peptides have proven especially suitable for occupying the broad and shallow ephrin-binding pocket of the Eph receptors with high affinity and selectivity, and can function as antagonists as well as agonists (Fig. 1B,C). Furthermore, independently of their modulatory effects on the Eph system, peptides conjugated to chemotherapeutic, radiosensitizing or chemosensitizing drugs can enhance the selective delivery of these agents to tumors overexpressing specific Eph receptors. In addition to their therapeutic use, peptides conjugated to imaging agents enable tumor visualization for early detection and diagnostic purposes, for monitoring therapy effectiveness, and for image-guided surgery [16-21]. Finally, peptides can also be incorporated as the targeting component of nanoparticles carrying therapeutic or diagnostic molecules, or both for dual modality theranostic applications [17, 21, 22].

STRATEGIES TO IDENTIFY PEPTIDES TARGETING THE EPHRIN-BINDING POCKET OF EPH RECEPTORS

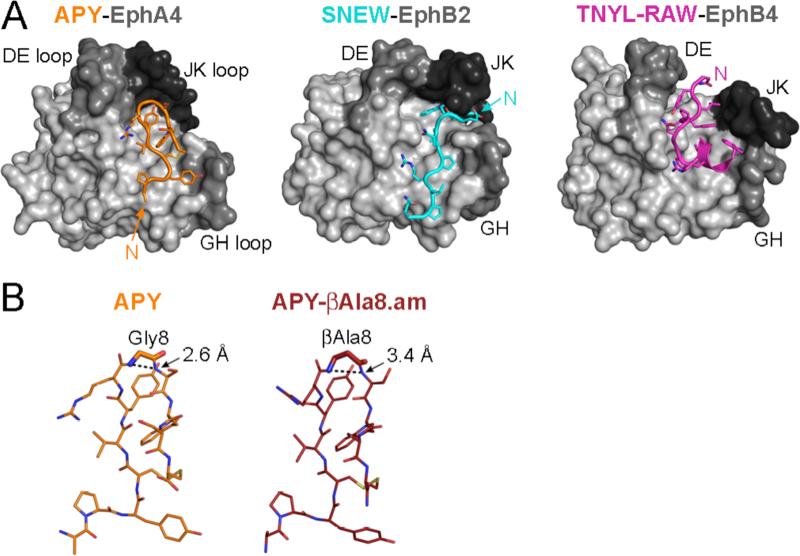

The most frequently used approach to identify peptides that bind to Eph receptors has been phage display. Screens of an M13 phage library displaying 12 amino acid-long peptides fused to the N terminus of the pIII minor coat protein have been particularly fruitful [23-25]. In these screens, the phage library was panned using the entire Eph receptor extracellular region immobilized in a well through an Fc or His tag. Several rounds of this panning resulted in a progressive enrichment of phage clones displaying peptides that target Eph receptors such as EphA2 [24], EphA4, EphA5, EphA7 [25], EphB1, EphB2 and EphB4 [23]. Remarkably, follow up characterization suggested that most, if not all, of the identified peptides bind to the ephrin-binding pocket of the target Eph receptor. For example, some of the identified peptides were chemically synthesized and found to antagonize ephrin binding to the target Eph receptor in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) [23-25]. They also antagonized the binding of the other phage clones targeting the same Eph receptor [23, 25, 26], suggesting partially overlapping binding sites. Additional evidence that some of the peptides bind to the ephrin-binding pocket includes NMR chemical shift perturbations that suggest an interaction of the peptides with residues of the ephrin-binding pocket [27, 28] and mutations of residues in the ephrin-binding pocket that affected peptide binding [27]. However, the most direct evidence comes from several X-ray crystal structures of peptide-Eph receptor complexes [29-31] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Peptides in complex with Eph receptors.

(A) Crystal structures of the APY peptide (orange) in complex with the EphA4 LBD (gray, PDB 4W5O), the SNEW peptide (cyan) in complex with the EphB2 LBD (gray, PDB 2QBX) and the TNYL-RAW (purple) in complex with the EphB4 LBD (gray, PDB 2BBA) illustrate the different binding modes of the peptides in the ephrin-binding pocket of their target Eph receptors. The peptides are shown in ribbon representation with side chains in stick representation and oxygens in red, nitrogens in blue, and the disulfide bond in yellow. The N terminus (N) of each peptide is also indicated. The Eph receptor LBDs are shown in light gray surface representation, with the DE, GH, and JK loops that line the ephrin-binding pocket in darker shades of gray. (B) Comparison of the β-turn in the APY and APY-βAla8.am peptides. The distances between the amides of G8 or βAla8 and S9 in the peptide β-turns (dotted lines) are indicated in the stick structures of the peptides (from peptide-EphA4 complexes PDB 4W5O and 4W4Z), showing a longer more favorable distance in APY-βAla8.am.

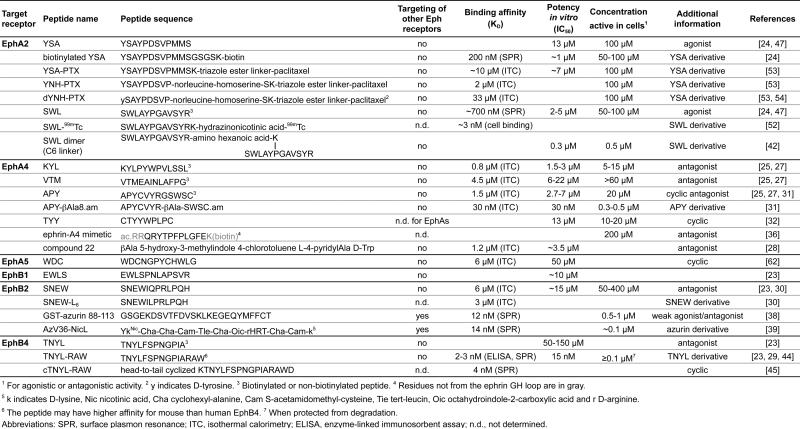

Overall, the best of the dodecameric peptides identified by phage display have binding affinities in the low micromolar range (Table 1). Another very important feature discovered for some of these peptide ligands is that they are highly selective and only bind to a single Eph receptor [23-25]. Although the phage library that has been most widely used displays peptides of 12 amino acids without specified attributes, 3 of the identified peptides contain 2 cysteines (separated by 4 or 7 intervening residues) enabling cyclization through formation of a disulfide bond [23, 25]. Cyclic peptides represent a particularly promising class of Eph receptor-targeting agents, since their constrained conformation offers the potential for higher binding affinity and specificity as well as better metabolic stability [9]. Accordingly, a phage display library of cyclic nonapeptides (CX7C) has also been panned on EphA4 leading to the identification of a peptide that in ELISAs inhibits EphA4-ephrin-A5 interaction at micromolar concentrations (TYY, Table 1) [32]. Additional phage display screens discovered cyclic CX7C peptides that bind to cultured cancer cells or that target mouse pancreatic islets in vivo [33-35]. Eph receptors were indirectly assigned as potential targets of some of these peptides, although further characterization is needed.

Table 1.

Peptides that target Eph receptors

An NMR spectroscopy detection approach was also used to screen a tripeptide combinatorial library for peptides binding to the EphA4 LBD [28]. An advantage of using NMR for detection is the ability to identify the Eph receptor residues that are perturbed upon ligand binding, thus potentially providing information on the peptide binding site early in the screening process. In detail, the synthetic combinatorial library screened by NMR was generated using 58 natural and non-natural amino acids (“fragments”) assembled into tripeptides in the “positional scanning” format. To evaluate a total of over 3,000 peptides, 174 peptide mixtures were screened, each with a specified amino acid at one position and random amino acids at the other two positions. The screen identified the best amino acid at each of the 3 fixed positions (i. e. the amino acid causing the largest chemical shift perturbations in the NMR spectra), leading to the generation of a tripeptide that binds to the ephrin-binding pocket of EphA4 with an estimated dissociation constant (KD) of ~200 μM, which was used as the starting point for further improvements (see below).

A third approach is to design peptides modeled on ephrins, since the ephrins bind to the ephrin-binding pocket mainly through part of a 15 amino acid-long loop (GH loop) [4], and peptides derived from the ephrin GH loop can also bind to Eph receptors. For example, a peptide corresponding to 12 amino acids from the ephrin-A3 GH loop was found to weakly bind a number of Eph receptors in ELISAs, with stronger binding to EphA1 and EphA8 [24]. Another peptide containing 11 amino acids from the ephrin-A4 GH loop (ephrin-A4 mimetic peptide; Table 1) can bind EphA4 in pulldown assays using rat brain extracts, although the potency and Eph receptor selectivity of this peptide have not yet been determined [36]. Computer-aided design of a cyclic peptide based on the ephrin-B2 GH loop to target the ephrin-binding pocket of EphB4 has also been reported, but the ability of the designed peptide to bind EphB4 and other Eph receptors remains to be experimentally verified [37]. Stabilization of the ephrin GH loop with a disulfide bond could represent a general strategy to generate Eph receptor-targeting cyclic peptides, although the feasibility of developing such peptides into high affinity and selective agents remains unknown.

Another rational approach was inspired by the similar overall structural fold of the copper-containing redox proteins cupredoxins with the Eph receptor-binding domain of the ephrins, with a study reporting that the bacterial cupredoxin azurin can bind tightly to EphB2 and EphA6 (but not EphA2 or EphA4) [38]. This study showed nanomolar binding of a GST-fused peptide corresponding to azurin amino acids 88-113 to a subset of Eph receptors, including EphB2 and EphA6, in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding studies (Table 1). It remains to be determined if the unpaired cysteine present in this azurin peptide may promote peptide dimerization in concert with the GST moiety or covalently react with an Eph receptor cysteine residue. Other surface plasmon resonance binding studies with synthetic peptides derived from azurin identified residues 108-122 as the most likely region of azurin involved in Eph receptor binding [39]. This second region, partially overlapping with that identified in the earlier study, served as the starting point for development of a highly modified derivative that binds with low nanomolar affinity to all 3 Eph receptors tested (EphA2, EphB2 and EphB4), although apparently with an unusual stoichiometry [39] (Table 1).

Finally, computer-based de novo rational design of peptides docking into the ephrin-binding pocket of Eph receptors with high affinity and selectivity would be very valuable, but this strategy is unlikely to be fruitful unless it can be guided by extensive experimental information gathered from the structures of a diverse repertoire of peptide-Eph receptor complexes. The major difficulty hindering computer-based peptide design is that the ephrin-binding pocket of the Eph receptors is defined by several flexible loops that can assume a range of sometimes widely divergent conformations when bound to different ligands or in their unbound forms [29-31, 40, 41].

BINDING FEATURES AND IMPROVEMENT OF EPH RECEPTOR-TARGETING PEPTIDES

After their discovery and initial evaluation, the most promising Eph receptor-targeting peptides have been further characterized, improved and used for a variety of applications. To date, the crystal structures of 4 peptides in complex with the EphA4, EphB2 or EphB4 LBDs have been solved (Fig. 2), revealing that peptides can bind to the ephrin-binding pocket in a variety of orientations [29-31]. However, a general requirement for high affinity peptide binding appears to be the formation of an interaction network capable of utilizing and stabilizing the flexible loops surrounding the ephrin-binding pocket, and particularly the highly flexible JK loop. Furthermore, the ability of several peptides to target only a single Eph receptor (despite the promiscuity in the binding of the ephrins to Eph receptors) suggests that the ephrin-binding pockets do have unique features that can be exploited by peptides to achieve strict selectivity. Promising peptides identified through various approaches typically have binding affinities in the low to high micromolar range. However, low nanomolar binding affinities have been achieved by modification of a linear peptide targeting EphB4 and a cyclic peptide targeting EphA4 [23, 31] (Table 1), which hints that subnanomolar affinities should be achievable, particularly through structure-guided peptide optimization. In addition, peptide dimerization or oligomerization can also drastically increase binding affinity through the increased avidity of multivalent binding [38, 42]. Peptide regions that make an important contribution to Eph receptor binding could in principle also be used as a starting point to design smaller derivatives, as exemplified by a peptide-based EphB4-targeting compound, which however exhibits an antagonistic potency of only ~20 μM [26], reflecting the challenge in achieving nanomolar binding affinities to the ephrin-binding pocket with small molecular weight compounds.

Besides a high binding affinity, additional properties are needed for in vivo use of peptides, including high resistance to plasma proteases and persistence in the blood circulation. N-terminal modifications to prevent digestion by aminopeptidases present in the blood [43], inclusion of unnatural amino acids, and cyclization have been successfully used to obtain more metabolically stable Eph receptor-targeting peptides [31, 44, 45]. In addition, PEGylation or inclusion into nanoparticles can prevent rapid clearance through the kidneys and the reticuloendothelial system, prolonging peptide lifetime in the circulation [19, 46]. The following sections provide detailed information on peptides targeting individual Eph receptors.

EphA2

The YSA and SWL dodecapeptides identified in phage display screens (Table 1) exhibit strict selectivity for EphA2 among the Eph receptors [24]. Alanine scans revealed that these two peptides share 4 identical residues that together with residues at 2 other conserved positions are critical for EphA2 binding, suggesting that these peptides interact in a similar manner with EphA2 [42, 47]. The two peptides target the EphA2 LBD, compete with each other for binding, and inhibit ephrin binding [24]. Thus, they both likely target the ephrin-binding pocket of EphA2, with the conserved proline P5 in YSA and P6 in SWL possibly contributing to the formation of a distinct backbone conformation that helps the peptide fit more stably into the pocket. Indeed, in silico molecular docking provided a model of each peptide bound within the ephrin-binding pocket of EphA2 [42, 47], which seems to be less conformationally variable than the pockets of other Eph receptors [48-50]. However, neither peptide has yet been crystallized in complex with the EphA2 LBD, which will be necessary to obtain conclusive information on their binding features. The unmodified YSA and SWL peptides have low micromolar antagonistic potency (<15 μM; Table 1), which can be substantially improved up to ~1 μM or less by C-terminal addition of lysine, biotin or other moieties attached through linkers [24, 51, 52]. Furthermore, dimerization of SWL with a 6-carbon linker was shown to yield a bivalent peptide with >10 fold increased potency (0.3 μM; Table 1) due to its simultaneously binding to 2 EphA2 LBDs [42].

The YSA and SWL peptides are quite stable in cell culture medium but not in plasma, where they are rapidly degraded, presumably mostly by aminopeptidases [43, 47, 53-55]. In addition, the YSA peptide contains two methionines, which are susceptible to oxidation. Modifications of YSA to improve metabolic stability, including replacement of Y1 (tyrosine 1) with D-tyrosine, M10 with norleucine and M11 with homocysteine, yielded dYNH, a peptide with >3 fold reduced binding affinity (Table 1) but greatly increased plasma stability [53, 54].

EphA4

A phage display screen to identify dodecapeptides binding to the EphA4 extracellular region identified 3 peptides (KYL, VTM and APY) that bind to the EphA4 LBD with low micromolar to submicromolar affinity and compete with each other for binding [25, 27] (Table 1). Mutagenesis identified residues in the ephrin-binding pocket of EphA4 that are needed for the binding of all 3 peptides but also other residues whose modification differentially affected the binding of each peptide, suggesting that there are common as well as distinctive features in the interaction of the 3 peptides with the ephrin-binding pocket of EphA4. In addition, several EphA4 mutations that disrupt ephrin-A5 binding do not similarly affect the binding of the peptides. This suggests substantial differences in the residues utilized for binding by the peptides and a natural ephrin ligand. This is in agreement with the strict selectivity of these peptides for EphA4, which is in contrast to the receptor binding promiscuity of ephrin-A5. In addition, systematic replacement of peptide residues revealed that 7 of the KYL residues and 8 of the VTM residues are critical for high affinity binding to EphA4 [27]. Measurement of peptide antagonistic activity after incubation in cell culture conditioned medium revealed that the KYL and APY peptides have a half-life of ~ 10 hours while VTM is stable for several days. However, all 3 peptides are rapidly degraded in plasma, with half-lives < 1 hour, which will have to be improved in derivatives to be used in vivo [27].

The KYL-EphA4 complex was modeled in silico by taking into account the perturbations of EphA4 LBD residues detected by NMR spectroscopy following KYL binding as well as the effects of modifications in KYL and EphA4 residues [27]. The model suggests that KYL occupies the ephrin-binding pocket in an extended conformation, with the N terminus near the GH loop of EphA4 and the C terminus between the JK and DE loops. The model also supports and important role of P7, which participates in direct contacts with EphA4 residues and induces a bend in the peptide backbone that favorably positions other peptide residues in the ephrin-binding pocket. A caveat is that the conformation of the flexible EphA4 loops surrounding the ephrin-binding pocket when it is occupied by KYL is not known, and therefore a crystal structure will be essential to unravel the precise molecular features of the KYL-EphA4 complex and enable peptide optimization.

Unlike KYL and VTM, which are linear, APY has a cyclic structure that results from a disulfide bond between C4 and C12 [25, 31]. APY has been crystallized in complex with the EphA4 LBD, illustrating the excellent fit of the peptide within the ephrin-binding pocket and the unique positioning of the surrounding DE, GH and JK loops of EphA4 in the complex (Fig. 2A). In particular, the GH and JK loops assume a “closed” conformation that could not accommodate the ephrin GH loop, besides being occupied and thus blocked by the peptide [31]. The crystal structure revealed not only a number of contacts between APY and EphA4 residues but also intramolecular hydrogen bonds within the peptide that stabilize its conformation and thus likely contribute to enhance its EphA4 binding affinity. Secondary phage display screens confirmed the importance of the peptide aromatic residues, consistent with their critical role revealed by the crystal structure, and also demonstrated a key binding role of residues outside the APY macrocycle. In contrast, APY residues 7, 9 and 11 could be replaced in the phage by a number of other amino acids (except proline) without loss of binding, consistent with their position on the solvent-exposed side of the peptide and suggesting that they could represent potential sites for APY derivatization.

Information from the crystal structure also suggested modifications for improving the binding affinity of APY [31]. One was amidation of the C terminus of APY, which resulted in an additional intrapeptide hydrogen bond. Another was to introduce a methylene spacer in the backbone of APY by replacing Gly8 with βAla in the tight β-turn at the apex of the circular portion of APY. The result was a decrease in the electrostatic repulsion between the amide groups of G8 and S9 (since the amide groups of βAla8 and S9 are further apart; Fig. 2B). These modifications resulted in the peptide APY-βAla8.am, which exhibits a binding affinity of 30 nM and retains strict selectivity for EphA4 (Table 1).

In addition to these peptides, a tripeptide targeting the EphA4 LBD that was identified in an NMR spectroscopy screen of a combinatorial library was further improved through progressive optimization cycles [28]. These cycles used a fluorescent polarization assay to measure inhibition of KYL binding to EphA4, NMR spectroscopy to monitor the interaction with the EphA4 LBD, and ELISAs to measure inhibition of EphA4-ephrin-A5 binding. Modification of side chains and elongation of the tripeptide led to compound 22, which has a molecular weight of ~800. This compound can selectively target EphA4 and has a long half-life of ~30 hours in mouse plasma in vitro, but additional modifications will be needed to further improve its 1.2 μM binding affinity (Table 1).

EphB2

Phage display screens identified SNEW as a dodecameric peptide that selectively binds to EphB2 with moderate affinity (KD = 6 μM) and inhibits EphB2-ephrin-B2 interaction in ELISAs with an IC50 value of 15 μM [23, 56] (Table 1). SNEW also inhibited EphB2 binding of the phage clones displaying all other peptides identified by panning on EphB2, suggesting that most of the identified peptides and ephrin-B2 share partially overlapping binding sites. Notably, 8 of the 13 peptides identified by panning on EphB2 also bound to EphB1, suggesting a particularly close similarity between the ephrin-binding pockets of the two receptors. The crystal structure of SNEW bound to the EphB2 LBD confirmed its binding to the ephrin-binding pocket (Fig. 2A) and revealed that SNEW causes an ordering of the loops surrounding the pocket that is distinct from that observed for the ephrin-B2-bound EphB2 receptor [30, 57]. The differences particularly highlight the plasticity of the JK loop. The overall SNEW-EphB2 binding interface is relatively small, consistent with the moderate binding affinity of the peptide [30]. The EphB2-bound peptide adopts an extended conformation, with an intrapeptide hydrogen bond between the side chains of N2 and W4, which appears to stabilize the peptide N-terminal region. The C-terminal H12 was not visible, suggesting that it is not rigidly positioned within the ephrin-binding pocket. Replacement of Q6 with leucine, which was suggested by an in silico combinatorial mutagenesis approach, improved the SNEW binding affinity by ~2-fold (Table 1) through an unclear mechanism [30]. Molecular dynamics simulations of SNEW in complex with EphB2 suggested that the first 4 residues of the SNEW peptide fit optimally in the ephrin-binding pocket, consistent with the crystal structure of the SNEW-EphB2 LBD complex, whereas C-terminal modifications could improve binding affinity [58]. However, several SNEW modifications predicted by computational methods to increase binding affinity failed to yield peptides that bind to EphB2 better than the original SNEW peptide, highlighting the difficulties in modeling ligands within the ephrin-binding pocket of an Eph receptor.

EphB4

For EphB4, phage display screens identified ~15 dodecameric peptides that preferentially bind to this receptor compared to the other EphB receptors [23]. Among a number of peptides that were chemically synthesized, TNYL was the best inhibitor of ephrin-B2 binding to EphB4, even though its potency was only 50-150 μM (for the biotinylated and non-biotinylated versions, respectively; Table 1). Besides antagonizing ephrin binding, TNYL also inhibited EphB4 binding of the phage clones displaying other peptides, suggesting that most of the identified peptides and ephrin-B2 share partially overlapping binding sites in EphB4. Interestingly, 9 of the peptides including TNYL have a conserved internal GP motif that could enable formation of a β-turn facilitating their fit within the ephrin-binding pocket of EphB4 [23]. Alignment of the sequences of the EphB4-targeting peptides based on the GP motif, which is followed by only 2 other residues in TNYL but is more central in other peptides, identified a RAW motif occurring in a position immediately following the last amino acid of TNYL. This motivated C-terminal extension of TNYL by addition of the RAW motif, which yielded TNYL-RAW. TNYL-RAW is a 15 amino acid-long peptide that exhibits a dramatically increased potency compared to TNYL (by 4 orders of magnitude, with an IC50 value of 15 nM and a KD value of 2-3 nM for the binding of TNYL-RAW to mouse EphB4; Table 1). TNYL-RAW also exhibits a slow dissociation rate and an enthalpy-driven binding mode [23, 44, 46, 59].

The crystal structure of TNYL-RAW bound to the EphB4 LBD (Fig. 2A) shows an extensive network of interactions between the peptide and residues in the ephrin-binding pocket, with the surrounding loops (particularly the JK loop) assuming a shifted position compared to ephrin-B2-bound EphB4 [29, 59]. Structural analysis also revealed the molecular determinants for the specificity of the TNYL-RAW-EphB4 interaction. TNYL-RAW binds in a different configuration compared to the ephrin-B2 G-H loop but interacts with some of the same EphB4 residues, including L48, L95 and T147 [29, 59]. Importantly, these residues are not conserved in other Eph receptors, most likely contributing to the selectivity of TNYL-RAW for EphB4. The bound peptide adopts an extended conformation in the N-terminal section preceding the central GP motif. The GP motif causes a sharp turn in the peptide backbone, which is followed by a pseudo α-helix formed by the RAW motif [29]. This motif contributes many critical contacts with EphB4, conferring the high binding affinity of TNYL-RAW compared to TNYL. Peptide residues Y3 and F5 also make important contacts with EphB4. In contrast, the N-terminal T1 and N2 do not appear to be critical for EphB4 binding, with T1 not even being visible in the crystal structure and thus representing an opportune point for derivatization to improve the pharmacological properties of TNYL-RAW. Indeed, the N-terminally truncated YL-RAW peptide has similar binding affinity as the original TNYL-RAW [29]. Based on its critical role in EphB4 binding, the RAW motif was used as a starting point to design a compound that is much smaller than TNYL-RAW (compound 5, with a molecular weight of ~600) but is still able to selectively target EphB4, albeit with much reduced antagonistic potency [26].

Stability studies revealed that TNYL-RAW has a very short half-life in cell culture medium and in plasma, suggesting high susceptibility to proteolytic degradation [46]. In addition, as expected for a short peptide, TNYL-RAW is rapidly lost from the blood circulation. Various strategies have been successfully used to inhibit peptide degradation and rapid blood clearance, including N-terminal modifications, conjugation to a 40 kDa branched polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymer or to nanoparticles, fusion to the Fc portion of an antibody, and complexation of the biotinylated peptide with streptavidin [44, 46, 60]. Interestingly, a study reported head-to-tail cyclization of a TNYL-RAW derivative containing an additional N-terminal lysine and C-terminal aspartic acid to yield cTNYL-RAW (Table 1). The cyclic cTNYL-RAW exhibits greatly increased stability in mouse plasma, presumably because the cyclic conformation inhibits peptide degradation by aminopeptidases as well as cleavage between R13 and A14 by trypsin-like proteases [45]. Surprisingly, cyclization did not appear to substantially reduce the high EphB4 binding affinity of TNYL-RAW, even though geometrical and distance considerations indicate that cyclization must affect the conformation of the peptide and thus of some of the EphB4-binding residues. A possible explanation could be that the flexible loops surrounding the ephrin-binding pocket of EphB4 rearrange to accommodate the modified peptide.

Other Eph receptors

Phage display screens were also performed using the EphA5, EphA7 and EphB1 receptors, which led to the identification of several peptides. The EphA7-binding peptides appeared to also bind to several other Eph receptors, at least when displayed on phage, and these peptides have not been further characterized [61]. The EphA5-binding peptides appeared to be more selective, which was confirmed with the chemically synthesized WDC peptide, a cyclic peptide that contains a GP motif [61, 62]. ELISAs showed that this peptide is an antagonist that inhibits ephrin-A5 binding to EphA5 with an IC50 value of ~50 μM. NMR studies showed perturbation patterns in the EphA5 LBD following WDC peptide binding, consistent with an interaction involving the ephrin-binding pocket. Of the EphB1 receptor-targeting peptides, EWLS is a selective EphB1 antagonist that inhibits ephrin-B2 binding in ELISAs with an IC50 value of ~10 μM and also competes for EphB1 binding with the other 4 peptides identified by panning on EphB1 [23]. Consistent with a close similarity of the EphB1 and EphB2 ephrin-binding pockets, 2 of the 5 peptides identified by panning on EphB1 can also bind to EphB2.

PEPTIDES MODULATING EPH RECEPTOR FUNCTION FOR RESEARCH AND THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS

Peptides that selectively target individual Eph receptors represent powerful research tools to investigate the biological activities of those receptors. They also constitute potential therapeutic leads to target specific Eph receptors for medical purposes. Most peptides bind to the ephrin-binding pocket of Eph receptors and are antagonists that inhibit Eph receptor-ephrin bidirectional signaling (Fig. 1B). However, the identified peptides targeting EphA2 were found to act as agonists (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, in principle dimerization or oligomerization of the peptides through linkers inducing appropriate Eph receptor clustering could transform peptide antagonists into agonists, although this remains to be demonstrated. Importantly, the development of peptides promoting or inhibiting Eph receptor signaling for disease treatment will have to proceed in parallel with better understanding of the complex activities of the Eph system in normal physiology and in pathological processes. The following is an overview of the use of the best available peptides to modulate signaling of individual Eph receptors.

EphA2

YSA, SWL and derivative peptides are agonists (Table 1 and Fig. 1C) that can promote EphA2 tyrosine phosphorylation (indicative of activation) and downstream signaling (including suppression of major oncogenic pathways such as RAS-ERK, AKT-mTORC1 and integrin-dependent pathways) as well as cause EphA2 degradation [24, 47]. However, it is not known how EphA2-binding peptides that appear to be monomeric can promote EphA2 activation, a process thought to require receptor dimerization/clustering. Perhaps YSA and SWL binding causes conformational changes in the EphA2 LBD (for example in the GH and JK loops), which may also affect surrounding regions of the receptor extracellular domain, making EphA2 molecules more prone to interact with each other. The agonistic effects of the peptides are similar to those of the natural ephrin-A ligands but weaker, which may at least in part stem from the lower binding affinity of the peptides. Thus, modifications to increase potency (for example through dimerization [42]) or the identification and improvement of new scaffolds will be needed to achieve more robust EphA2 activation triggered by peptide agonists. Such higher affinity derivatives would also be more amenable to further development into therapeutic leads. These agents would then be useful to promote EphA2 activation, which is low in many tumors consistent with the fact that ephrin-induced EphA2 signaling can suppress tumorigenesis [5]. On the other hand, EphA2 activation in endothelial cells is an important factor in pathological forms of angiogenesis. Thus antagonistic peptides, if they could be developed, could be useful to inhibit angiogenesis.

EphA4

The KYL, VTM, APY and APY-βAla8.am peptides (Table 1) are antagonists that can inhibit ephrin-induced EphA4 activation in in vitro biochemical assays [63], in cultured cells, and in mouse hippocampal slices [25, 27, 31]. Although APY-βAla8.am with its nanomolar binding affinity is the most potent of the EphA4 peptide antagonists, it was only recently developed and therefore so far most studies have used KYL as a research tool and to validate EphA4 as a potential drug target. Thus, KYL was used in cell culture and ex vivo models to implicate EphA4 in various biological processes as well as in rodent preclinical studies demonstrating the role of EphA4 in neuroprotection and neural repair. For example, treatment of chick embryo trunk organotypic explants with KYL implicated EphA4 in restricting the segmental migration of neural crest cells to the rostral sclerotome [25]. KYL was also used in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures to demonstrate that EphA4 is responsible for specifying the degree of structural plasticity of developing mossy fiber synapses according to topographic principles [64]. Supporting a role for EphA4-ephrin interaction in axon guidance and inhibition of nerve regeneration after injury, KYL and very recently APY-βAla8.am were shown to inhibit EphA4-dependent growth cone collapse in retinal explants and/or cultures of cortical neurons [31, 65, 66]. Furthermore, inhibition of colony formation and increased cell death in neural stem cell cultures treated with KYL contributed to implicate ephrin-induced EphA4 signaling in the viability of different types of neural stem cells [67].

Importantly, KYL has also been used to corroborate the role of EphA4 signaling in neurodegenerative processes. Two studies have shown that blockage of the EphA4 LBD by KYL can inhibit EphA4 activation by amyloid-β oligomers, which are believed to play an important role in the synaptic dysfunction and cognitive impairment characteristic of Alzheimer's disease [68, 69]. KYL can reverse the pathologic effects of amyloid-β oligomers in cell-based models of Alzheimer's disease, including the loss of synaptic structures, impairment of synaptic plasticity and neuronal apoptosis. Furthermore, intracerebral infusion of KYL was shown to restore normal synaptic plasticity in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease [69]. In a rat model of spinal cord injury, KYL administered intrathecally enhanced the sprouting of injured axons as well as recovery of limb function [65], suggesting potential medical applications to promote nerve repair after injury by inhibiting ephrin-induced EphA4 signaling. Moreover, intracerebral infusion of KYL significantly delayed disease onset and increased survival in a rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a lethal neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive loss of motor neurons and for which therapy options are nearly absent [70, 71]. Thus, KYL has served as a prototype for therapeutic agents targeting EphA4 and promoting neural repair and neuroprotection by blocking ligand-induced EphA4 signaling.

Besides the application of KYL to inhibit neurodegenerative processes, a peptide mimicking the ephrin-A4 GH loop (Table 1) was also shown to inhibit ephrin-induced EphA4 activation in brain slices [36]. A study in which this antagonistic peptide was stereotactically microinjected in the lateral amigdala implicated EphA4 in the establishment of long-term fear memory in a rat fear conditioning model [36]. This suggests that pharmacological inhibition of EphA4 (and/or other Eph receptors that may be targeted by the peptide) could also help treat fear and anxiety disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder. The peptide also seemed to impair the formation of fear memory when administered systemically, although its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier has not yet been measured.

In other applications outside the nervous system, the KYL peptide has been used in cell culture experiments to demonstrate the importance of ephrin-induced EphA4 activation in limiting integrin-mediated T-cell adhesion to endothelial cells, suggesting a role for EphA4 in regulating T-cell trafficking in vivo [72]. Finally, KYL was used in a co-culture model to demonstrate that interaction of EphA4 upregulated in breast cancer stem cells with ephrins expressed in a monocyte cell line elicits juxtacrine signals that induce secretion of cytokines sustaining the stem cell state [73]. This helped define EphA4 as a key receptor that mediates the interplay of breast cancer stem cells with monocytes and macrophages serving as niche cells that support breast cancer malignancy. Finally, the cyclic TYY peptide (Table 1) was show to inhibit HUVE cell capillary-like tube formation without cytotoxicity, with detectable effects at concentrations of 10-20 μM [32]. This result supports a role for EphA4 in angiogenesis, although this particular peptide might also target other EphA receptors with a role in angiogenesis [74].

EphB2 and EphB4

With respect to targeting EphB receptors, the EphB2-binding peptide SNEW and the EphB4-binding peptide TNYL-RAW are antagonists that can suppress signaling by both EphB2 or EphB4 and their ephrin-B ligands [23] (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). As such, SNEW and TNYL-RAW can inhibit the ephrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of their target EphB receptor as well as tyrosine phosphorylation of ephrin-B ligands, which is mediated by kinases such as SRC [23, 46, 75-77]. This ephrin-B tyrosine phosphorylation is induced by interaction with the LBD of EphB receptors expressed in neighboring cells, in a process called reverse signaling [1, 5, 78].

Given their selectivity, the SNEW and TNYL-RAW peptides have been used as tools in studies to implicate EphB2, EphB4 or both receptors in various biological processes. SNEW can block COS and human umbilical vein endothelial (HUVE) cell retraction caused by ephrin-induced EphB2 activation [23] and TNYL-RAW can block HUVE cell retraction caused by ephrin-induced EphB4 activation [79], indicating the ability of the peptides to counteract the cell shape changes and anti-migratory effects mediated by the EphB2 and EphB4 receptors. Additionally, TNYL-RAW was found to promote mesenchymal features in MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells, as indicated by loss of intercellular junction integrity mediated by EphB4-ephrin-B2 [80]. Both SNEW and TNYL-RAW have also been used in in vitro experiments demonstrating the importance of EphB receptor-ephrin-B2 signaling in the angiogenic responses of endothelial cells and their supporting vascular mural cells [46, 75, 76]. These studies also support the potential utility of SNEW and TNYL-RAW for inhibition of pathological forms of angiogenesis, such as retinal vascular diseases and tumor angiogenesis [3, 81]. Furthermore, TNYL-RAW has been shown to perturb the integrity of cell-cell junctions in HUVE cells, implicating EphB4 in venous endothelial barrier function and thus, for example, in the control of venous vascular integrity [82].

In addition, treatment of embryonic stem cells with the TNYL-RAW peptide was shown to impair their in vitro differentiation along the cardiac lineage, implicating EphB4 in this process [83]. Moreover, SNEW and TNYL-RAW were used to discriminate the importance of EphB2 and EphB4 interaction with ephrin-Bs in a variety of other signaling processes. For example, treatment with SNEW and TNYL-RAW has contributed to highlighting effects of ephrin-B2 on endothelial cell morphology and motility that do not depend on its interaction with the EphB2 and EphB4 receptors [79]. Furthermore, treatment of COS cells with the SNEW peptide was shown to inhibit COS cell retraction induced by the secreted neuronal glycoprotein Reelin [84]. This, together with other studies, supports a role for EphB2 as a receptor that could mediate some of the effects of Reelin on neuronal migration and other processes in the developing and adult brain.

Another key function of EphB4 and ephrin-B2 is regulation of bone homeostasis, which experiments with the TNYL-RAW and SNEW peptides have helped characterize. For example, treatment of a bone marrow stromal cell line with TNYL-RAW (but not with SNEW) was found to reduce the expression of genes involved in the differentiation of cells that form bone (osteoblasts) concomitantly with inhibition of mineralization, supporting a role for EphB4-ephrin-B2 signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation [85-87]. Incubation of osteoblasts with TNYL-RAW can also enhance the differentiation of co-cultured osteoclast precursors, which together with other evidence demonstrated that EphB4-ephrin-B2 signaling in osteoblasts can restrict osteoclast formation, likely by decreasing the production of secreted osteoclast differentiation factors [77]. Treatment with TNYL-RAW also supported a role for EphB4-ephrin-B2 mediated cell-cell communication in the anabolic effects of insulin-like growth factor 1, including chondrocyte differentiation [88]. Finally, the SNEW and TNYL-RAW peptides have been used to implicate EphB2/EphB4-ephrin-B interaction in the inhibition of activated T-cell proliferation induced by contact of T-cells with mesenchymal stem cells and leading to immunosuppression, suggesting that peptides targeting EphB2 and EphB4 could be used for immunomodulation [89].

Finally, in some cancers EphB2 and EphB4 can promote tumorigenesis by interacting with ephrin-B ligands [5, 81, 90]. This opens the possibility of using antagonist peptides for cancer therapy in these scenarios, an application that however needs to be further explored. Along these lines, a study using the azurin 88-113 peptide fused to GST (Table 1) to treat DU145 prostate cancer cells overexpressing EphB2 showed inhibition of ephrin-induced EphB2 tyrosine phosphorylation concomitant with inhibition of cell growth at a peptide concentration of ~1 μM [38].

PEPTIDE CONJUGATES TARGETING EPH RECEPTORS

In addition to the potential of free peptides, peptides can be very valuable when conjugated with other molecules. Applications of such conjugates are, for example, the selective delivery of imaging or therapeutic agents to cells and tissues with high expression of a target Eph receptor. Generally, peptides have several favorable features as conjugated targeting agents compared to antibodies, including ease of synthesis, low immunogenicity and toxicity, ability to modify a well-defined site for conjugation ensuring a homogeneous targeting agent, and a small size that enables more efficient tissue penetration [9-12, 91]. In addition, peptides can not only escort drugs to target tissues but also help make them more soluble and bioavailable [92, 93]. The rapid blood clearance and low non-specific accumulation of unmodified peptides in most normal organs can also be an advantage for certain applications in medical imaging, for example by reducing undesirable side effects that might arise with prolonged exposure [16, 18, 52]. Thus, Eph receptor-binding peptides can be directly conjugated to a cargo molecule as well as serve as the targeting component of nanoparticles containing imaging agents, drugs, gold for photothermal therapy, and siRNAs for gene knockdown. Nanoparticles can also be used to deliver combinations of molecules, such as diagnostic and therapeutic agents for theranostic applications. Nanoparticles also have the benefit that they can protect peptides from rapid degradation and clearance from the blood circulation as well as enhance binding to targets through the increased avidity afforded by the multivalency of the incorporated peptides. On the other hand, the relative small size of peptides makes them particularly desirable for use as the targeting agents of nanoparticles for an increasingly wide variety of sophisticated applications [91, 94-97].

Among the Eph receptors, EphA2 and EphB4 have been most extensively explored for targeted delivery to tumors because of their high and widespread expression in cancer cells and the tumor vasculature but low levels in most normal tissues [5]. For example, a recent study has shown that EphA2 is the most abundant cell surface protein in osteosarcoma cells while being expressed at low levels in healthy bone tissue, and is therefore an excellent candidate for targeted drug delivery in this type of cancer [98]. In addition, EphA2 expression in the absence of ephrin-induced activation has been associated with cancer stem cells and with epithelial-mesenchymal transition [99-102], suggesting that agonistic peptides that bind to EphA2 may not only enable targeting of the most malignant and therapy-resistant cancer cells but also in parallel trigger the tumor suppressing effects of EphA2 signaling.

Accordingly, soon after its discovery the YSA peptide was shown to promote the binding of phage particles to cultured cancer and endothelial cells expressing EphA2 [24]. Phage-displayed SWL appeared to be less effective, but could nevertheless target phage particles to cancer cells overexpressing transfected EphA2. These studies provided the first proof-of-concept that peptides can be used for targeted delivery to Eph receptor-expressing cells. They have been followed by a number of other studies on the development of Eph receptor-targeting peptides conjugated to imaging agents, therapeutics and nanoparticles, which are outlined in detail in the next sections.

Eph receptor-targeting peptide conjugates in medical imaging

Non-invasive molecular imaging of tumors can be used to facilitate early detection and diagnosis as well as to monitor the effectiveness of anticancer therapies and guide surgical excision of tumors, altogether improving patient outcomes. The potential of Eph receptor-binding peptides as probes for molecular imaging is demonstrated by their successful use in a number of imaging applications. In initial studies, biotinylated YSA, KYL and TNYL immobilized on streptavidin-coated fluorescent quantum dots were successfully used to visualize cultured cells expressing the EphA2, EphA4 or EphB4 receptors, respectively [23, 27, 51, 53]. In addition, YSA-coated PEGylated lipid nanoparticles loaded with a fluorescent dye have been used for imaging cultured lung cancer cells with high EphA2 levels (EphA2-positive) and nanoparticles loaded with luciferin have been used for in vivo bioluminescent imaging of EphA2-positive mouse mammary tumors expressing luciferase [103]. Furthermore, fluorescein-labeled TNYL-RAW but not a scrambled peptide was shown to label EphB4-positive PC3M prostate cancer and CT26 mouse colon cancer cells in culture but not A549 lung cancer cells, which have very low EphB4 expression (EphB4-negative) [44].

Radiolabeled peptides can be useful for both molecular imaging of tumors and radiotherapy. This prompted recent work using a modified version of the EphA2-targeting SWL peptide where R12 was replaced by a lysine whose side chain was radiolabeled through the addition of an 18F-chelating group [55]. However, this particular SWL derivative peptide did not demonstrate detectable binding to an EphA2-overexpressing melanoma cell line, suggesting that its binding affinity is insufficient for effective targeting. Furthermore, the radiolabeled peptide was unstable in rat plasma and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging revealed rapid clearance from the mouse blood circulation and accumulation in the kidneys and bladder. Derivatives of the EphB2-targeting SNEW peptide were also radiofluorinated using different strategies, but PET imaging after intravenous injection of the best 18F-labelled SNEW derivative in rats similarly revealed very brief retention in the blood accompanied by metabolism and rapid renal elimination [104, 105]. Thus, besides potency, the in vivo stability of the radiofluorinated SWL and SNEW peptides needs to be improved in order to enable their use for tumor imaging. More encouraging results have been obtained with a form of the SWL peptide labeled with technetium-99m, the short-lived metastable nuclear isomer of technetium-99 [52]. This peptide derivative was recently successfully developed for single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging of EphA2-expressing cells. For this, a lysine residue was added to the SWL C terminus with a hydraxinonicotinc acid chelating group linked to its side chain, resulting in SWL-99mTc (Table 1). In contrast to the R12 replacement outlined above, these modifications seemed to greatly increase the EphA2 binding affinity of the peptide from macromolar to low nanomolar. This SWL derivative enabled specific visualization of the EphA2-positive A549 lung cancer cells in culture and in mouse xenografts in vivo. Thus, the SWL-99mTc peptide shows good potential to be developed for medical diagnostic procedures.

The TNYL-RAW peptide appears particularly well suited for cancer imaging, given its very high EphB4 binding affinity (Table 1) and slow dissociation rate [44]. Accordingly, various derivatives have been developed for use in various imaging modalities with very promising results. N-terminal modification with the radiometal chelator DOTA followed by loading with 64Cu yielded a promising radiotracer for PET-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging [44]. The 64Cu-DOTA-TNYL-RAW has EphB4 binding affinity similar to that of the unmodified peptide (2-3 nM) and is reportedly rather stable in biological fluids (>2 hour half-life when incubated in mouse serum at 37°C) as needed for imaging, presumably because the N-terminal chelating group protects it from aminopeptidase digestion [46]. The peptide was successfully used to image EphB4-positive PC3 prostate cancer and CT26 colon cancer cells in mouse tumor xenografts by small animal PET-CT. Another version of the peptide, Cy5.5-TNYL-RAWK-64Cu-DOTA (labeled with the near infrared dye Cy5.5 at the N terminus and with 64Cu-DOTA attached to an added C-terminal lysine) was developed for dual modality microPET-CT and near-infrared fluorescence optical imaging of orthotopic glioblastoma xenograft mouse models [20]. This derivative also retained high EphB4 binding affinity. When systemically administered in mice with intracranial tumors derived from EphB4-expressing U251 cells, Cy5.5-TNYL-RAWK-64Cu-DOTA labeled both the tumor cells and the tumor vasculature. In a control, labeling was restricted to the vasculature of tumors derived from the EphB4-negative U87 cells. The implications of these results are two fold. First, the staining of the U251 tumor cells suggests that the TNYL-RAW derivative was able to cross the blood brain barrier, which can be compromised to a certain degree in tumors and could be further disrupted by TNYL-RAW-mediated targeting of endothelial EphB4-ephrin-B2 [82, 106]. Second, the tumor vasculature was also visualized using this approach, which could represent a way to monitor tumors by imaging their blood vessels through EphB4 targeting.

In a different approach, the TNYL-RAW peptide was conjugated through an N-terminal cysteine to long-circulating PEG-coated core-crosslinked polymeric micelles [19]. These nanoparticles were loaded with the near-infrared fluorescent dye Cy7 and the gamma emitter 111Indium bound to the DTPA chelating agent. This allowed the simultaneous visualization of mouse tumor xenografts derived from the EphB4-expressing PC3 prostate cancer cells using both radionuclide and optical imaging. Additionally, as expected, the micelle formulation greatly increased the peptide lifetime in the circulation compared to the unconjugated monomeric peptide. Multiple controls demonstrated the specificity of the various labeled TNYL-RAW derivatives for EphB4-expressing tumors. In particular, low labeling was observed in controls using EphB4-negative A549 tumor xenografts, including an excess unlabeled peptide as a competitor and substituting a scrambled peptide for TNYL-RAW [19, 20, 44]. In summary, these sophisticated multimodal imaging probes based on the TNYL-RAW peptide offer the advantage of combining different features that can be used for different applications. For example, the high detection sensitivity of PET or SPECT imaging, which is based on radiolabeled probes, can be useful for detection of EphB4-expressing tumors whereas optical imaging, which has high resolution but low tissue penetration depth, is superior for highlighting tumor margins during surgical resection thus potentially improving patient progression-free survival [20].

Eph receptor-binding peptide conjugates for targeted therapies

Since chemotherapeutic drugs typically have high systemic toxicity, it is desirable to increase their selective delivery to tumors. This can reduce the drug exposure of normal cells, thus limiting adverse side effects, and enable achievement of higher drug doses at the tumor site [45, 91]. One way to achieve tumor selective delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs is their conjugation to peptides targeting cell surface receptors that are highly expressed in tumors [17, 91], such as EphA2 and EphB4. In addition, the EphA2-targeting YSA and SWL peptides and their derivatives are agonists that cause EphA2 activation as well as in endocytosis, and therefore promote not only delivery to tumors but also transport of conjugated agents to intracellular compartments [24, 51, 53, 107]. Interestingly, several mechanisms of YSA peptide-triggered EphA2 endocytosis have been described, including macropinocytosis [107]. This process, involving to the formation of large endocytic vesicles carrying extracellular fluids and macromolecules, represents a potentially powerful mechanism for the uptake of drugs even if they are not physically linked to the targeting peptide [108]. Internalized EphA2 has been detected in lysosomes, implying that agents conjugated to EphA2 peptide agonists could be released following lysosomal degradation of the peptide, representing a potentially elegant and effective drug delivery system [51, 53]. Thus, new classes of therapeutic peptide conjugates could be developed to exploit EphA2 receptor activation and internalization for drug delivery into cancer cells.

Accordingly, anti-tumor activities have been reported for the EphA2-targeting YSA peptide and its derivatives YNH and dYNH conjugated to paclitaxel through a triazole ester linker [51, 53] (Table 1) or a more stable linker [54]. These peptides have been shown to enhance the anti-tumor effects of the chemotherapeutic drug paclitaxel in a PC3 prostate cancer mouse xenograft model and to decrease vascularization in a mouse syngeneic renal cancer model without overt signs of toxicity [51, 53, 54]. These effects may result from a combination of targeted paclitaxel delivery to tumors and vascular cells (as suggested by comparison with a scrambled peptide) and an increased solubility of paclitaxel conjugated to the peptides [54, 92, 93]. Importantly, this improved solubility could avoid the complex formulations and long infusion times needed for patients treated with unconjugated paclitaxel. In addition, white blood cell counts remained in the normal range in mice treated with YSA conjugated to paclitaxel compared to the lower counts in mice treated with an equivalent dose of unconjugated paclitaxel, suggesting that attachment to the YSA peptide can decrease the systemic toxicity of paclitaxel [54]. The YSA peptide has also been used in other targeted delivery systems being developed for cancer treatment. For example, YSA-coated PEGylated lipid nanoparticles loaded with a combination of docetaxel (a first line chemotherapeutic agent in lung cancer) and DIM-C-pPhC6H5 (a PPRγ agonist with anticancer activity) were found to inhibit the growth of orthotopic and metastatic mouse lung cancer xenografts more effectively than non-targeted nanoparticles, without detectable toxicity [103].

The YSA peptide fused to the homodimeric p19 siRNA-binding protein or conjugated to the outer shell of hydrogel nanoparticles has also been successfully used to deliver functional siRNAs inside EphA2-positive ovarian cancer cells in culture, leading to siRNA-mediated gene knockdown [107, 109, 110]. Intracellular siRNA delivery was greatly reduced by competition with excess free peptide and in controls without the YSA peptide or with EphA2-negative cells, demonstrating its dependence on EphA2. Furthermore, both the p19-YSA carrier and YSA-functionalized nanoparticles lacked the high toxicity observed with the cationic lipids or polymers generally used for siRNA transfection. Thus, YSA-targeted delivery systems could be developed to exploit the many therapeutic applications of RNA interference in cancer and other diseases by selectively delivering siRNA inside EphA2-positive cells. As an example, nanogels functionalized with the YSA peptide and encapsulating siRNA targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor can sensitize EphA2-positive but not EphA2-negative ovarian cancer cells in culture to the chemotherapeutic drug docetaxel [110].

The use of the YSA peptide attached through a PEG linker to polyaspartic acid and coated on anisotropic gold nanoparticles (nanorods) has also been recently explored for both imaging with near infrared light and photothermal cancer therapy [111]. Although several thousand peptide molecules were immobilized on each gold nanorod, YSA only slightly increased the uptake of the nanorods into cultured PC3 prostate cancer cells in comparison with fibroblasts with low EphA2 expression or in comparison with a control peptide (with N- to C-terminal reversed amino acid sequence and thus unlikely to bind EphA2). This suggests a high level of non-targeted uptake of the nanorods and thus the need to further develop this system to achieve selective delivery.

In non-cancer applications, YSA-coupled PEGylated lipids have been used to prepare liposomes encapsulating the DNA damaging agent doxorubicin for treatment of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization in a rat model system [112]. YSA-targeted liposomes were more efficiently taken up by EphA2-positive retinal pigmented epithelial cells in culture than control non-targeted liposomes. Furthermore, after intravitreous injection they reduced the area of choroidal neovascularization more effectively than the control liposomes, and without the toxicity observed with the administration of free doxorubicin. Given the widespread upregulation of EphA2 in angiogenic vasculature [5], intravitreally injectable YSA-targeted lyposomes could be developed for angiogenesis-related ocular pathologies, such as choroidal neovascularization in age-related macula degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and corneal angiogenesis.

Adenoviruses show promise as vectors for gene therapy and vaccination, and as oncolytic agents [113-115]. However, safe use of adenoviruses in the clinic requires engineering their capsid proteins to redirect their tropism from healthy cells to specific diseased cells of interest, for example by genetic insertion of short peptide ligands targeting specific cell surface receptors. The YSA peptide, which can be encoded by the adenovirus genome because it contains only natural amino acids and which can also promote adenovirus internalization through EphA2 activation [51], shows particular promise for adenoviral transduction of EphA2-positive cancer cells. Several studies with YSA-redirected adenoviruses have demonstrated efficient EphA2-dependent transduction of endothelial, osteosarcoma and pancreatic cancer cells in culture as well as of ex vivo slices from patient-derived pancreatic tumors and melanoma metastases [98, 113, 116, 117]. Successful in vivo transduction of pancreatic cancer and melanoma xenografts in the mouse was also observed after intratumor adenovirus injection but not yet through systemic adenovirus administration, which represents the next goal. The SWL peptide used in one study also enabled adenovirus infection of EphA2-positive cells, although slightly less effectively than the YSA peptide [117].

The TNYL-RAW peptide has been conjugated to various nanoparticles for controlled delivery of anticancer agents to EphB4-positive cells. Promising effects of such conjugates were observed in various mouse xenograft models. In one study the cyclic version of the peptide (cTNYL-RAW, Table 1) was conjugated through a PEG linker to hollow gold nanospheres, which absorb in the near-infrared region and have strong photothermal conduction [45]. These nanospheres were additionally loaded with the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin. The peptide selectively targeted the nanospheres to several EphB4-positive cancer cells in culture and in mouse tumor xenografts after intravenous injection. Near-infrared irradiation of Hey ovarian tumor xenografts after intravenous injection of the gold nanospheres resulted in 2 therapeutic modalities: photothermal heating damaging tumor cells and local release of the entrapped doxorubicin. This caused complete regression of most tumors without obvious systemic toxicity. In comparison, irradiated doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles without the TNYL-RAW targeting peptide were less effective and did not eradicate tumors. Nanoparticles without doxorubicin, on the other hand, allowed substantial tumor growth after irradiation, and even more rapid growth was observed for irradiated tumors in mice injected with saline control. Thus, targeting EphB4 with the cTNYL-RAW peptide can enhance laser-controlled chemo-photothermal therapy of tumors through a single gold nanoparticle delivery system. In a second study, TNYL-RAW was used to target glycolipid-like polymer micelles containing hollow gold nanospheres and paclitaxel to EphB4-expressing tumor cells for use with near-infrared irradiation to induce photothermal tumor cell damage and paclitaxel release [60]. In vivo imaging of the nanoparticles loaded with the near-infrared dye DiR demonstrated preferential accumulation in EphB4-positive SKOV3 xenografts than in EphB4-negative A549 xenografts, but the effects of the paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles on tumor xenograft growth were not reported. A third study used the TNYL-RAW peptide to selectively target hollow carbon nanotubes encapsulating a cytotoxic small molecule (indole) to EphB4-expressing transfected HeLa cells in culture [118]. This system is also controllable by using heating from near-infrared irradiation to promote photothermal cell damage as well as the release of encapsulated cytotoxic molecules leading to cell killing, which was dependent on functionalization of the nanotubes with the TNYL-RAW peptide.

The TNYL peptide has also been conjugated through a C-terminal PEG linker to chitosan-g-stearate, generating an amphiphilic polymer that spontaneously forms nanosized micelles in aqueous solutions, which can be efficiently loaded with drugs or imaging agents and can be readily internalized into cells [119]. Despite the low EphB4 binding affinity of monomeric TNYL [23], the peptide could preferentially target doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles to EphB4-positive SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells compared to non-targeted nanoparticles, leading to enhanced toxicity towards the cancer cells [119]. In addition, in vivo imaging showed that the TNYL-targeted nanoparticles could preferentially deliver the encapsulated near-infrared dye DiR to SKOV3 mouse tumor xenografts compared to EphB4-negative A549 lung cancer xenografts.

Finally, an Eph receptor-targeting peptide conjugate also showed promise for radiosensitization of cancer cells. The AzV36-NicL peptide derived from azurin and carrying the radiosensitizer nicotinamide (Table 1) was reported to target the EphA2, EphB2 and EphB4 receptors with nanomolar affinity and to be stable in serum [39]. AzV36-NicL was found to enhance the effects of irradiation in an in vitro clonogenic assay with Lewis lung cancer cells as well as to increase the in vivo efficacy of radiotherapy against Lewis lung mouse subcutaneous tumors and lung metastatic colonies, with no obvious signs of toxicity.

Other applications of Eph receptor-targeting peptide conjugates

In an additional approach, cobalt ferrite magnetic nanoparticles containing fluorescently labeled YSA conjugates have been used to isolate/remove EphA2-positive ovarian cancer cells from peritoneal fluids of experimental mice as well as patients using a strong magnet [120, 121]. This approach could be useful to extract cancer cells present in various body fluids, for example to assess their drug sensitivity or analyze gene expression profiles and mutations, and possibly even to remove cancer cells that may seed metastases. Circulating tumor cells may be captured with this approach, provided that EphA2 expression in normal blood cells is sufficiently low.

PERSPECTIVES

Peptides are being increasingly used as the agents of choice for targeting the ephrin-binding pocket of the Eph receptors. Phage display has been a successful strategy for the identification of Eph receptor-targeting peptides of moderate (micromolar) affinity, which have proven to be amenable to further improvements to increase potency, stability and in vivo half-life. Expanding the scope of the phage display approach, the recently developed platforms involving “on phage” chemical modification of the displayed peptides could also be explored to identify more diverse, potent and stable peptides directly in the initial screens [122-124]. Additionally, the implementation of cyclic scaffolds can yield a peptide configuration particularly well suited for occupying the dynamic ephrin-binding pocket of Eph receptors and representing a promising starting point for improvement towards therapeutic entities [31].

The best and most widely used Eph receptor-targeting peptides identified so far selectively bind to the ephrin-binding pockets of the EphA2, EphA4, EphB2 and EphB4 receptors and have a wide spectrum of potential applications including in cancer and vascular pathologies, neurodegenerative diseases, regenerative medicine and many others. The EphA2 and EphB2 targeting peptides, however, still need to be improved to achieve nanomolar affinity. Hopefully future efforts will identify a collection of nanomolar peptides that can be used to specifically target the ephrin-binding pocket of each of the 14 Eph receptors, through either the improvement of some of the moderate affinity peptides already available or the identification of new peptides. It may also be desirable to obtain peptides that target other Eph receptor extracellular regions besides the ephrin-binding pocket, which could be useful when blocking ephrin binding is undesirable. In addition, targeting the Eph system could also be accomplished through peptides that bind to the ephrins. However, to our knowledge such peptides have not yet been identified and it remains to be seen whether the ephrin extracellular region or Eph receptor extracellular domains other than the LBD include suitable surfaces that can accommodate peptides capable of high binding affinity.

Further challenges in developing Eph receptor-targeting peptides for medical applications exist, but recent progress in the area of peptide therapeutics is encouraging [9-12]. As new peptides targeting Eph receptors are discovered and improved, they will serve as tools to further elucidate the biology of each Eph receptor. This will also help define the potential medical applications of targeting each member of the large Eph receptor family as well as the possible unwanted side effects. Finally, as outlined in this review, Eph receptor-targeting peptides also have great potential as conjugates for both imaging and therapeutic purposes. Thus, expansion of the available peptide collection to target all 14 Eph receptor family members represents an exciting, promising and powerful undertaking in biomedical research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors’ work is supported by the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- KD

dissociation constant

- LBD

ligand-binding domain

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PET-CT

positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- SPECT

single-photon emission computed tomography

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors are inventors in patents/patent applications on Eph receptor–targeting peptides and have received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to develop these peptides.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pasquale EB. Eph receptor signalling casts a wide net on cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:462–75. doi: 10.1038/nrm1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lisabeth EM, Falivelli G, Pasquale EB. Eph receptor signaling and ephrins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barquilla A, Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins: therapeutic opportunities. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55 doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140226. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Himanen JP. Eph-ephrin interaction: from structural biology to cell functions. Curr Drug Targets. 2015 this issue. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:165–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caflisch A. Targeting the Eph system with kinase inhibitors. Curr Drug Targets. 2015 this issue. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lodola A, Tognolini M. Targeting the Eph system with protein-protein inhibitors. Curr Drug Targets. 2015 doi: 10.2174/1389450116666150825144457. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craik DJ, Fairlie DP, Liras S, Price D. The future of peptide-based drugs. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2013;81:136–47. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nestor JJ., Jr. The medicinal chemistry of peptides. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:4399–418. doi: 10.2174/092986709789712907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albericio F, Kruger HG. Therapeutic peptides. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:1527–31. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahrens VM, Bellmann-Sickert K, Beck-Sickinger AG. Peptides and peptide conjugates: therapeutics on the upward path. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:1567–86. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richard JP, Melikov K, Vives E, Ramos C, Verbeure B, Gait MJ, et al. Cell-penetrating peptides. A reevaluation of the mechanism of cellular uptake. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:585–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones AT, Sayers EJ. Cell entry of cell penetrating peptides and tales of tails wagging dogs. J Control Release. 2012;161:582–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shete HK, Prabhu RH, Patravale VB. Endosomal escape: a bottleneck in intracellular delivery. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;14:460–74. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.9082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okarvi SM. Recent progress in fluorine-18 labelled peptide radiopharmaceuticals. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:929–38. doi: 10.1007/s002590100508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reubi JC. Peptide receptors as molecular targets for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:389–427. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen K, Conti PS. Target-specific delivery of peptide-based probes for PET imaging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1005–22. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang R, Xiong C, Huang M, Zhou M, Huang Q, Wen X, et al. Peptide-conjugated polymeric micellar nanoparticles for Dual SPECT and optical imaging of EphB4 receptors in prostate cancer xenografts. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5872–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang M, Xiong C, Lu W, Zhang R, Zhou M, Huang Q, et al. Dual-modality micro-positron emission tomography/computed tomography and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of EphB4 in orthotopic glioblastoma xenograft models. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16:74–84. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray BP, Brown KC. Combinatorial peptide libraries: mining for cell-binding peptides. Chem Rev. 2014;114:1020–81. doi: 10.1021/cr400166n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelkar SS, Reineke TM. Theranostics: combining imaging and therapy. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:1879–903. doi: 10.1021/bc200151q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koolpe M, Burgess R, Dail M, Pasquale EB. EphB receptor-binding peptides identified by phage display enable design of an antagonist with ephrin-like affinity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17301–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]