Abstract

Objective To determine the impact of the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program—the US pay for performance program introduced by Medicare to incentivize higher quality care—on 30 day mortality for three incentivized conditions: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia.

Design Observational study.

Setting 4267 acute care hospitals in the United States: 2919 participated in the HVBP program and 1348 were ineligible and used as controls (44 in general hospitals in Maryland and 1304 critical access hospitals across the United States).

Participants 2 430 618 patients admitted to US hospitals from 2008 through 2013.

Main outcome measures 30 day risk adjusted mortality for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia using a patient level linear spline analysis to examine the association between the introduction of the HVBP program and 30 day mortality. Non-incentivized, medical conditions were the comparators. A secondary outcome measure was to determine whether the introduction of the HVBP program was particularly beneficial for a subgroup of hospital—poor performers at baseline—that may benefit the most.

Results Mortality rates of incentivized conditions in hospitals participating in the HVBP program declined at −0.13% for each quarter during the preintervention period and −0.03% point difference for each quarter during the post-intervention period. For non-HVBP hospitals, mortality rates declined at −0.14% point difference for each quarter during the preintervention period and −0.01% point difference for each quarter during the post-intervention period. The difference in the mortality trends between the two groups was small and non-significant (difference in difference in trends −0.03% point difference for each quarter, 95% confidence interval −0.08% to 0.13% point difference, P=0.35). In no subgroups of hospitals was HVBP associated with better outcomes, including poor performers at baseline.

Conclusions Evidence that HVBP has led to lower mortality rates is lacking. Nations considering similar pay for performance programs may want to consider alternative models to achieve improved patient outcomes.

Introduction

Healthcare systems around the world are striving to deliver high quality care while controlling costs. One compelling strategy is the use of financial incentives to reward high value care.1 2 The US federal government has made substantial efforts to shift towards value based payments since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010.3 4 5 One key program is Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) introduced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2011. HVBP rewards or penalizes hospitals based on their performance on multiple domains of care, including clinical processes, clinical outcomes (eg, 30 day mortality for acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and heart failure), patient experience, and, more recently, cost efficiency.6 7 Funding for HVBP is designed to be budget neutral; Medicare withholds a percentage of inpatient payments to prospectively paid hospitals and then redistributes this money back to hospitals based on their performance. In fiscal year 2015, HVBP led to penalties for 1360 hospitals and bonus payments to 1700 hospitals.8

HVBP was based on the US premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration, similar to the Advancing Quality program in England. These programs, both of which were pay for performance schemes that rewarded hospitals based primarily on performance on clinical process measures, showed modest early improvements in processes of care though no long term effect on patient outcomes.9 10 11 12 13 HVBP is different from these programs because it is both national in scope and not voluntary, unlike prior pay for performance schemes among self selected hospitals that might be more likely to respond. Performance is determined based on hospitals’ absolute achievement compared with the national average, or improvement compared with their own performance in the baseline period, depending on which is greater (see supplementary appendix 1 for more details). Many pay for performance programs focus only on bonuses for better performance, but HVBP also uses penalties; therefore, advocates argue that the current HVBP program should be more likely to improve outcomes than its predecessors because of hospitals’ concerns about loss avoidance.14 15 16 US hospitals are now more than three years into the national HVBP pay for performance program, without clear evidence of its impact on patient outcomes. Early results in the first year of the program indicate that there has been no observed effect on clinical process measures or patient experience after the introduction of the financial incentives17; although one might imagine that it would take longer for hospitals to change care as a response to financial incentives. Given the upcoming increase in the HVBP penalty, up to 2% for fiscal year 2017, and more countries considering a move towards national penalties to incentivize quality,2 4 understanding the impact of this national program on patient mortality, arguably the most important outcome, is essential.

We used national Medicare data to answer three questions. Firstly, what effect has the HVBP program had on patient mortality for the targeted conditions, three years after implementation, compared with hospitals ineligible for the program? Secondly, did effects on trends in mortality for targeted conditions differ from those of a comparable group of non-targeted conditions? And finally, given prior evidence that certain types of hospitals may generally have a greater incentive to improve quality in pay for performance schemes,18 19 were improvements in mortality particularly noticeable in a subset of hospitals (eg, those that were poor performers at baseline)?

Methods

Data

Using the 100% Medicare inpatient claims data from 2008 through 2013, we examined all hospital stays for Medicare fee for service beneficiaries who were admitted with any of the three conditions targeted by HVBP: acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia. In the HVBP program these conditions are directly incentivized. They were identified using diagnosis related group and ICD-9 codes (international classification of diseases, ninth revision) based on the CMS methodology. To compile a comparison group, we collected information on nine most common non-surgical discharge diagnoses not targeted by HVBP: stroke, sepsis, gastroenteritis and esophagitis, gastrointestinal bleed, urinary tract infection, metabolic disorder, arrhythmia, and renal failure. We excluded patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, respiratory tract infection, and chest pain because of their close clinical overlap with the target conditions. Supplementary table A provides a full list of these codes. Patients could be included in the sample more than once over the six year period; we considered each diagnosis as independent. We also excluded patients enrolled in hospice services prior to admission and patients who left hospitals against medical advice, since they are omitted from the CMS calculation for HVBP performance.

Our treatment group was composed of acute care hospitals that participated in the HVBP program. The comparison group was hospitals in Maryland and critical access hospitals since they were not affected by the HVBP program. Maryland is exempt from the program because it participates in an alternative hospital regulation system where the state sets its own payment rates, and critical access hospitals are exempt due to a government waiver that protects these hospitals. Of note, Maryland and critical access hospitals are the only available group of US hospitals with data available to researchers to be used for comparison. We also excluded other ineligible hospitals, including children’s hospitals, hospitals specializing in psychiatric and cancer care, and federal hospitals. We used the American Hospital Association annual survey to obtain data on hospital characteristics, including size, ownership, teaching status, location, region, and the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid as the primary payer.

We also obtained information on three other covariates of interest based on prior data showing that the greatest improvements under the premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration occurred in hospitals that were eligible for large bonuses (determined by their proportion of patients insured with Medicare), had good financial health (as indicated by positive total margins), and were located in the least competitive markets (measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman index).18 We used the American Hospital Association survey to obtain the proportion of Medicare patients for each hospital and the Herfindahl-Hirschman index for each market; the total margin for each hospital was obtained from the Medicare hospital cost reports.12

Statistical analysis

We first compared the characteristics of hospitals and patients between hospitals participating in HVBP and those not participating. We then compared the adjusted 30 day mortality over time between the two hospital groups. We used patient level linear spline analyses to compare the trends in mortality before and after the introduction of the HVBP program in the participating hospitals, and, secondly, to compare the change in trends between the two hospital groups. Thirdly, we investigated whether the change in trend in mortality of target conditions differed from a comparable group of the most common non-surgical conditions within the HVBP hospitals. We define these additional non-surgical conditions as “non-targeted conditions” since they are not incentivized by the HVBP program.

In the patient level analyses we used mortality within 30 days as the outcome, and a random effects linear spline model to assess the trend during the preintervention period (first quarter of 2008 through second quarter of 2011), and during the post-intervention period (third quarter of 2011 to fourth quarter of 2013). We measured time in quarters and treated it as a continuous variable. The random effect for hospitals follows CMS methodology and accounts for correlation between patients within each hospital and for correlation over time. The models were adjusted for patient comorbidities using the hierarchical condition categories developed by CMS,20 as well as indicator variables for seasonal variation. In addition to the comparison of the linear trend during the preintervention period with the linear trend during the post-intervention period, we added an indicator variable for non-HVBP hospitals so that interaction terms between the slope estimates and the non-HVBP indicator would allow us to compare the change in trend between HVBP and non-HVBP hospitals. We run these models for each of the three conditions as well as for one composite model, using patients with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia, which also included indicator variables for the three targeted conditions. Finally, we combined the patient data for both targeted and non-targeted conditions from HVBP hospitals, and, using an indicator variable for non-targeted conditions and its interactions with the preintervention and post-intervention slopes, we tested whether the change in mortality trend was different for targeted conditions than for non-targeted conditions.

In sensitivity analyses, we used the same model as above to compare the risk adjusted 30 day mortality rates between HVBP hospitals with Maryland hospitals alone or with critical access hospitals alone. Additionally, we analyzed the data using logistic regression models, with hospital specific fixed effects as a sensitivity analysis to ensure the robustness of our findings.

Finally, we performed a subgroup analysis on HVBP hospitals with the worse adjusted mortality rate at baseline. We calculated the mean mortality rate across the three targeted conditions for each hospital during the preintervention period. We defined poor performers as 25% of HVBP hospitals with the worst risk adjusted 30 day mortality. For each poor performing HVBP hospital, we identified all non-HVBP hospitals that had a mean mortality rate within 0.01% of the HVBP hospital during the preintervention period. We chose one such non-HVBP hospital at random for the match. Then, using these matched groups, we compared the trends in mortality before and after the introduction of the HVBP program between the poor performing HVBP hospitals and the matched control hospitals. We also conducted stratified analyses by proportion of Medicare population (indicating size of incentive), hospital financial status, and local levels of competition.

All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

Hospital and patient characteristics

We had complete data for our analyses on 2919 hospitals participating in the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program and 1348 hospitals not eligible for the program, of which 44 were based in Maryland and 1304 were critical access hospitals (see supplementary table B). Compared with the control hospitals, those participating in the HVBP program were more likely to be large, of teaching status, and not for profit (table 1). HVBP hospitals were also more likely to be located in the south, whereas non-HVBP hospitals (excluding Maryland) were more likely to be located in the Midwest. HVBP hospitals cared for 2 252 818 patients, whereas non-HVBP hospitals cared for 177 800 patients. Patients in HVBP hospitals were slightly younger, more likely to be male, black, and to have Medicaid insurance (table 2). They were also slightly more likely to have hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease, and less likely to have congestive heart failure compared with patients in control hospitals.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitals participating and not participating in US Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | HVBP hospitals (n=2919) | Non-HVBP hospitals* (n=1348) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean annual Medicare volume | 2671 | 385 |

| Hospital size: | ||

| Small | 808 (27.7) | 1249 (92.7) |

| Medium | 1676 (57.4) | 91 (6.8) |

| Large | 435 (13.9) | 8 (0.6) |

| Ownership: | ||

| For profit | 594 (20.4) | 71 (5.30 |

| Private not for profit | 1892 (64.8) | 734 (54.5) |

| Public | 433 (14.8) | 543 (40.3) |

| Teaching status: | ||

| Major | 262 (9.0) | 6 (0.5) |

| Minor | 699 (24.0) | 86 (6.4) |

| Non-teaching | 1958 (67.1) | 1256 (93.2) |

| Region: | ||

| North east | 474 (16.2) | 66 (4.9) |

| Midwest | 698 (23.9) | 627 (46.5) |

| South | 1187 (40.7) | 386 (24.5) |

| West | 560 (19.2) | 269 (20.0) |

| Median (interquartile range) proportion Medicaid patients | 18.0 (13.3-22.9) | 11.6 (6.7-17.6) |

| Median (interquartile range) proportion Medicare patients | 47.5 (41.5-53.4) | 57.8 (50.5-69.1) |

*Include 44 hospitals in Maryland and 1304 critical access hospitals.

P values <0.001.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients at hospitals participating and not participating in US Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program. Values are percentages (numbers) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | HVBP hospitals | Non-HVBP hospitals* | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients | 2 252 818 | 177 800 | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 79.8 (8.3) | 81.0 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| Male | 42.1 (948 436) | 39.5 (70 231) | <0.001 |

| Race: | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 84.7 (1 908 137) | 87.7 (155 931) | <0.001 |

| Black | 10.4 (234 293) | 9.8 (17 424) | |

| Hispanic | 2.0 (45 056) | 0.6 (1067) | |

| Other | 2.9 (65 332) | 1.9 (3378) | |

| Comorbidities: | |||

| Hypertension | 70.5 (1 588 237) | 63.6 (113 081) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 31.3 (705 132) | 29.8 (52 984) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 15.1 (340 176) | 16.4 (29 159) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 6.1 (137 422) | 6.0 (10 668) | 0.54 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 24.1 (542 929) | 23.6 (41 961) | 0.13 |

| Renal failure | 19.3 (434 794) | 15.8 (28 092) | <0.001 |

*Include 44 hospitals in Maryland and 1304 critical access hospitals.

Mortality trends between HVBP and non-HVBP hospitals

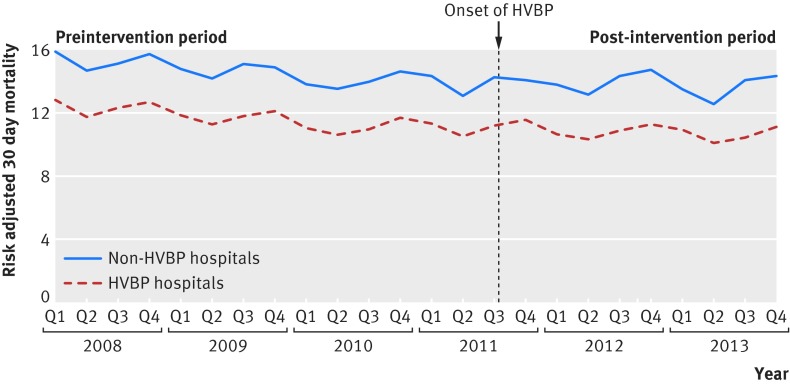

Figure 1 shows the time trends of 30 day risk adjusted mortality rates for target conditions for HVBP compared with non-HVBP hospitals. The trends in mortality in the preintervention period were similar between HVBP and non-HVBP hospitals (−0.13% v −0.14% for each quarter, P=0.16). After the introduction of HVBP in July 2011, the rate of improvement in adjusted mortality slowed to a −0.03% point difference for each quarter for HVBP hospitals and a −0.01% point difference for each quarter for non-HVBP hospitals (table 2). Using a formal test for differences in the change in mortality trend between HVBP and non-HVBP hospitals, the introduction of the HVBP program was not associated with a statistically significant change in trend in the mortality rate for target conditions (change in trends in mortality rate 0.10% point difference for each quarter in HVBP hospitals versus 0.13% point difference for each quarter in control hospitals, P=0.35, table 2). These findings were consistent when Maryland hospitals or critical access hospitals were used alone as a comparison series (see supplementary tables C, D, and G). They were also consistent when we applied a logistic regression model with hospital fixed effects (see supplementary table E).

Fig 1 Risk adjusted 30 day mortality rates for target conditions between hospitals participating or not participating in the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program, 2008 to 2013

Mortality trends for target versus non-target conditions

When we examined the mortality trend for target conditions versus non-target conditions within HVBP hospitals, the rate of change in mortality did not differ significantly (0.10% point difference for each quarter versus 0.09% point difference for each quarter, respectively, difference in difference in trend of 0.01% point difference for each quarter, P=0.12, table 3, see supplementary table F).

Table 3.

Trends in mortality between hospitals participating and not participating in US Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program

| Variables | Quarterly change in mortality (%) | Difference (95% CI) in difference in trend (% point difference) | P value for difference in difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVBP hospitals | Non-HVBP hospitals* | |||

| Target conditions: | ||||

| Preintervention | −0.13 | −0.14 | −0.03 (−0.08 to 0.13) | 0.35 |

| Post-intervention | −0.03 | −0.01 | ||

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.10 (0.09 to 0.12) | 0.13 (0.08 to 0.18) | ||

| Acute myocardial infarction: | ||||

| Preintervention | −0.18 | −0.18 | 0 (−0.19 to 0.19) | 0.98 |

| Post-intervention | −0.04 | −0.05 | ||

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.14 (0.10 to 0.18) | 0.14 (−0.05 to 0.33) | ||

| Congestive heart failure: | ||||

| Preintervention | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.05 (−0.13 to 0.04) | 0.27 |

| Post-intervention | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.10 (0.07 to 0.12) | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.22) | ||

| Pneumonia: | ||||

| Preintervention | −0.15 | −0.15 | −0.04 (−0.11 to 0.04) | 0.35 |

| Post-intervention | −0.07 | −0.03 | ||

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.10) | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.18) | ||

| Non-target conditions†: | ||||

| Preintervention | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.03) | 0.61 |

| Post-intervention | −0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.08) | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.10) | ||

*Include 44 hospitals from Maryland and 1304 critical access hospitals.

†Include stroke, esophagitis/gastritis, gastrointestinal bleed, urinary tract infection, metabolic disease, arrhythmia, and renal failure. See supplementary table 6 for mortality of individual non-target conditions.

Impact of HVBP program by hospital characteristics

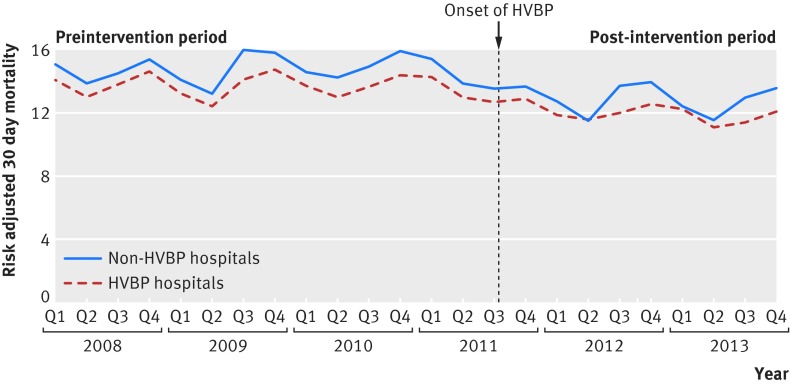

We examined the impact of the HVBP program on a subset of hospitals that may benefit the most from a pay for performance program. Firstly, we evaluated the impact of HVBP on poor performing hospitals, by matching 733 hospitals participating in the HVBP program one to one with non-HVBP hospitals (fig 2). The baseline mean adjusted mortality for the target conditions for HVBP hospitals was 14.0% (SD 1.4%) compared with 13.6% (SD 1.3%) for the non-HVBP hospitals. The change in trend between the poor performing HVBP hospitals and a matched group of control hospitals did not differ significantly (−0.20% point difference for each quarter versus −0.23% point difference for each quarter, respectively, P=0.50) (see supplementary table H). Also, the association between the introduction of the HVBP program and improvement in patient mortality was not statistically significant when stratification was carried out by the size of the potential financial incentive, hospitals’ financial health, and market competitiveness (see supplementary table I).

Fig 2 Mortality by target conditions at 30 days among hospitals with poor performance at baseline, 2008-13. HVBP=Hospital Value-Based Purchasing

Discussion

Three years after the introduction of the US national pay for performance program—Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP)—we find no evidence that it has led to better patient outcomes. The trends in mortality for the target conditions among hospitals participating in HVBP actually slowed after the program’s introduction, although that slowing was also seen among hospitals not participating in the program. Even among hospitals with worst patient mortality at baseline, a group of hospitals that had arguably more motivation to improve to avoid penalties, we found no evidence that HVBP drove improvement beyond secular trends observed in a matched group of non-HVBP hospitals. Taken together, these findings call into question the effectiveness of the national hospital pay for performance program and whether it is having the desired effect on patient outcomes.

This study has important implications for international efforts using financial incentives to drive improvements in hospital quality of care. The program on which HVBP was based, the US Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration, also failed to improve patient outcomes.12 Some critics argued that prior pay for performance programs based purely on attainment did not motivate poor performers to improve (since they were unlikely to improve enough to earn bonuses) and also did little for higher performers who would have received bonuses even by maintaining their status.21 22 However, HVBP was modified to include financial incentives for both achievement and improvement to ensure that all hospitals had some motivation to improve.14 Further, as a national non-voluntary program, HVBP was posited to be more impactful because it was not focused on a voluntary group of hospitals that might have been high performers at baseline. Despite these advantages, we found no evidence that HVBP improved patient outcomes. Given the amount of time and resources spent in its design and implementation, these findings are discouraging and should motivate policymakers to consider changes in the structure and size of incentives in ways that may lead to meaningful improvements in patient care versus completely rethinking the utility of pay for performance programs that target hospital quality.13 23

It is unclear why this pay for performance program had little effect on patient outcomes. It may be that given the plethora of measures, US hospitals focused primarily on a few measured processes and patient experience scores but made little effort to improve underlying processes in ways that led to better outcomes. Another possible explanation for a lack of impact is that the public reporting of performance on these conditions, which began in 2008,24 may have already extracted most of the gains in improving patient outcomes. Though that is possible, we think it is unlikely for several reasons. Firstly, the evidence to date suggests that public reporting has had little impact on improvements in patient outcomes.25 26 Secondly, although the Maryland hospitals were subjected to public reporting, the critical access hospitals were not, and therefore would have been unlikely to have improved dramatically from public reporting during the period prior to the onset of HVBP.

Comparison with other studies

These results add to a growing body of literature that suggest many pay for performance programs are largely ineffective in improving patient outcomes.27 28 As further emphasis on value-based programs continues to grow, healthcare policymakers should carefully consider the costs of investing in these pay for performance programs29 and the potential unintended consequences.30 31 32 Ultimately, these programs need to be evaluated based on weighting the benefits and harms they create—and our work suggests that the benefits seem to be small, if present at all. Given prior studies that have suggested that pay for performance programs lead to potential changes in diagnostic coding practices or risk avoidance,33 34 using a more robust evidence base—or certainly willingness to make changes when programs seem not to be working—should be an important approach that policymakers need to consider. In light of our negative finding, policymakers should consider new approaches to achieving better clinical outcomes.

We are unaware of previous studies that have robustly evaluated the impact of HVBP on patient mortality multiple years into the program. One study evaluated the short term impact (year 1) of HVBP on patient satisfaction and clinical process measures and found no effect.17 A recent report from the US Government Accountability Office that looked at trends over time following the introduction of the HVBP program came to a similar conclusion.35 Our findings further strengthen these results using a quasi-experimental methodology that compares hospitals participating in the HVBP program with multiple control groups as opposed to simply looking at trends over time. These findings are also consistent with evaluations of similar previous pay for performance programs. A study examined the impact of the US premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration, the program that HVBP was modeled after, and found modest improvements in processes of care.9 However, two other studies found no influence of this program on patient mortality.12 25 Similarly, a third study found no meaningful long term improvements in mortality in England’s Advancing Quality program, despite initial optimistic reports.10

Strengths and limitations of this study

There are limitations to our study. Firstly, although no major reform was introduced in Maryland hospitals during the study period, they were subject to a different set of financial incentives starting in 2008. However, by evaluating the trends of mortality in the preintervention period between groups, we confirmed that Maryland hospitals are an appropriate comparison group. In addition, we also ran the models with critical access hospitals, which were not subjected to any kind of pay for performance around these conditions, and our findings were similar. Further, although not the ideal controls, Maryland hospitals and critical access hospitals are the only comparison hospitals available in the United States. Secondly, we compared trends in mortality within HVBP hospitals of target conditions to those not targeted by financial incentives, which may also be affected by the HVBP program through spillover effects, although we tried our best to remove conditions that were clinically similar. Thirdly, we used administrative data, which may be limited in its ability to account for medical severity of illness between hospitals and across time. If medical severity of illness is changing over time in ways that our current risk adjustment methodology cannot account for, then the effect of HVBP may be more difficult to identify. Finally, we only have data for three years after the implementation of the HVBP program. Improving an outcome such as 30 day mortality may take longer than our study period, and it may require complex system changes and multi level approaches, which in turn may take longer to observe an effect. Future studies are needed to examine longer term effects.

Conclusions and policy implications

We found that the introduction of the US HVBP program was not associated with lower 30 day mortality. This study suggests that we have yet to identify the appropriate mix of quality metrics and incentives to improve patient outcomes. As countries continue to move towards achieving value-based care, these findings hold important lessons and call for a greater understanding of how to achieve better outcomes under this framework.

What is already known on this topic

Evidence shows that pay for performance programs are largely ineffective in improving patient outcomes

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) is a pay for performance program introduced in the United States in 2011 that incentivizes hospitals based on performance on clinical processes; patient outcomes, including 30 day mortality; patient experience; and cost efficiency

Early results in the first year of the program indicated no effect on clinical process measures or patient experience, but the impact of HVBP on patient mortality is unknown

What this study adds

The introduction of the HVBP program was not associated with an improvement in 30 day mortality of Medicare beneficiaries admitted to US hospitals

Nations considering similar pay for performance programs may want to consider alternative models to achieve improved patient outcomes

Web extra.

Web extra material supplied by authors

Web extra: supplementary information

Contributors: All authors conceived and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. AKJ acquired the data. JZ, JFF, and YT carried out the statistical analysis. JFF drafted the manuscript. AKJ supervised the study and is the guarantor.

Funding: This study received no support from any organization.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICJME uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was reviewed and granted exemption by the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Office of Human Research Administration.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1.Kristensen SR, Bech M, Quentin W. A roadmap for comparing readmission policies with application to Denmark, England, Germany and the United States. Health Policy 2015;119:264-73. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.12.009 pmid:25547401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cashin C, Chi YL, Smith P, Borowitz M, Thomson S. Paying for Performance in Health Care: Implications for health system performance and accountability. 2014th Ed Open University Press. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutler DM. Payment reform is about to become a reality. JAMA 2015;313:1606-7. 10.1001/jama.2015.1926 pmid:25919512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services. Better Care. Smarter Spending. Healthier People: Paying Providers for Value, Not Volume. CMS.gov. 2015. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-01-26-3.html.

- 5.Burwell SM. Setting Value-Based Payment Goals—HHS Efforts to Improve U.S. Health Care. N Engl J Med 2015;372:897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services. Hospital Value-Based Purchasing. CMS.gov. 2014. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/.

- 7.QualityNet. Hospital Value Based Purchasing Overview. QualityNet.org. 2016. www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier2&cid=1228772039937.

- 8.Rau J. 1,700 Hospitals Win Quality Bonuses From Medicare, But Most Will Never Collect.Kaiser Health News, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med 2007;356:486-96. 10.1056/NEJMsa064964 pmid:17259444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristensen SR, Meacock R, Turner AJ, et al. Long-term effect of hospital pay for performance on mortality in England. N Engl J Med 2014;371:540-8. 10.1056/NEJMoa1400962 pmid:25099578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glickman SW, Ou F-S, DeLong ER, et al. Pay for performance, quality of care, and outcomes in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2007;297:2373-80. 10.1001/jama.297.21.2373 pmid:17551130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jha AK, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. The long-term effect of premier pay for performance on patient outcomes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1606-15. 10.1056/NEJMsa1112351 pmid:22455751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha AK. Time to get serious about pay for performance. JAMA 2013;309:347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VanLare JM, Conway PH. Value-based purchasing—national programs to move from volume to value. N Engl J Med 2012;367:292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Rational choice and the framing of decisions. J Bus 1986;59:S251-78.. 10.1086/296365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrad DA. Incentives for healthcare performance improvement. In: Smith PC, Mossialos E, Papanicolas I, Leatherman S, eds. Performance Measurement for Health System Improvement.Cambridge University Press, 2010;582-612. 10.1017/CBO9780511711800.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan AM, Burgess JF, Pesko MF, Borden WB, Dimick JB. The early effects of medicare’s mandatory hospital pay-for-performance program. Health Serv Res 2015;50:81-97.pmid:25040485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werner RM, Kolstad JT,, Stuart EA, Polsky D. The effect of pay-for-performance in hospitals: lessons for quality improvement. Health Aff 2011;30:690-8 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenthal MB, Frank RG, Li Z, Epstein AM. Early experience with pay-for-performance: from concept to practice. JAMA 2005;294:1788-93. 10.1001/jama.294.14.1788 pmid:16219882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P, Kim MM, Doshi JA. Comparison of the performance of the CMS Hierarchical Condition Category (CMS-HCC) risk adjuster with the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity measures in predicting mortality. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:245 10.1186/1472-6963-10-245 pmid:20727154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenthal MB, Fernandopulle R, Song HR, Landon B. Paying for quality: providers’ incentives for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:127-41. 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.127 pmid:15046137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal MB, Frank RG. What is the empirical basis for paying for quality in health care?Med Care Res Rev 2006;63:135-57. 10.1177/1077558705285291 pmid:16595409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werner RM, Dudley RA. Medicare’s new hospital value-based purchasing program is likely to have only a small impact on hospital payments. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1932-40. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0990 pmid:22949441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bratzler DW, Normand SLT, Wang Y, et al. An administrative claims model for profiling hospital 30-day mortality rates for pneumonia patients. PLoS One 2011;6:e17401 10.1371/journal.pone.0017401 pmid:21532758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joynt KE, Blumenthal DM, Orav EJ, Resnic FS, Jha AK. Association of public reporting for percutaneous coronary intervention with utilization and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2012;308:1460-8. 10.1001/jama.2012.12922 pmid:23047360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan AM, Nallamothu BK, Dimick JB. Medicare’s public reporting initiative on hospital quality had modest or no impact on mortality from three key conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:585-92. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0719 pmid:22392670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eijkenaar F, Emmert M, Scheppach M, Schöffski O. Effects of pay for performance in health care: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Health Policy 2013;110:115-30. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.01.008 pmid:23380190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kontopantelis E, Springate DA, Ashworth M, Webb RT, Buchan IE, Doran T. Investigating the relationship between quality of primary care and premature mortality in England: a spatial whole-population study. BMJ 2015;350:h904 10.1136/bmj.h904 pmid:25733592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casalino LP, Gans D, Weber R, et al. US physicians practices spend more than $15.4 billion annually to report quality measures. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:401-6. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1258 pmid:26953292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lester HE, Hannon KL, Campbell SM. Identifying unintended consequences of quality indicators: a qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:1057-61. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048371 pmid:21693464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bardach NS, Cabana MD. The unintended consequences of quality improvement. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009;21:777-82. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283329937 pmid:19773653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eappen S, Lane BH, Rosenberg B, et al. Relationship between occurrence of surgical complications and hospital finances. JAMA 2013;309:1599-606. 10.1001/jama.2013.2773 pmid:23592104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003-2009. JAMA 2012;307:1405-13. 10.1001/jama.2012.384 pmid:22474204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen TT, Chung KP, Lin IC, Lai MS. The unintended consequence of diabetes mellitus pay-for-performance (P4P) program in Taiwan: are patients with more comorbidities or more severe conditions likely to be excluded from the P4P program?Health Serv Res 2011;46:47-60. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01182.x pmid:20880044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Government Accountability Office. Initial Results Show Modest Effects on Medicare Payments and No Apparent Change in Quality-of-Care Trends. GAO Report 2015;(Oct):1–49.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web extra: supplementary information