Abstract

Objectives

Investigating for the first time in Germany Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fifth Edition (DSM-5) prevalences of adolescent full syndrome, Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED), partial and subthreshold anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED).

Method

A national school-based cross-sectional survey with nine schools in Germany was undertaken that was aimed at students from grades 7 and 8. Of the 1775 students who were contacted to participate in the study, 1654 participated (participation rate: 93.2%). The sample consisted of 873 female and 781 male adolescents (mean age=13.4 years). Prevalence rates were established using direct symptom criteria with a structured inventory (SIAB-S) and an additional self-report questionnaire (Eating Disorder Inventory 2 (EDI-2)).

Results

Prevalences for full syndrome were 0.3% for AN, 0.4% for BN, 0.5% for BED and 3.6% for OSFED-atypical AN, 0% for BN (low frequency/limited duration), 0% for BED (low frequency/limited duration) and 1.9% for purging disorder (PD). Prevalences of partial syndrome were 10.9% for AN (7.1% established with cognitive symptoms only, excluding weight criteria), 0.2% for BN and 2.1% for BED, and of subthreshold syndrome were 0.8% for AN, 0.3% for BN and 0.2% for BED. Cases on EDI-2 scales were much more pronounced with 12.6–21.1% of the participants with significant sex differences.

Conclusions

The findings were in accordance with corresponding international studies but were in contrast to other German studies showing much higher prevalence rates. The study provides, for the first time, estimates for DSM-5 prevalences of eating disorders in adolescents for Germany, and evidence in favour of using valid measures for improving prevalence estimates.

Trial registration number

DRKS00005050; Results.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This cross-sectional survey estimates, for the first time, prevalence rates of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fifth Edition (DSM-5) full syndrome adolescent anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder and Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED), partial and subthreshold eating disorders in Germany.

Prevalence rates were investigated with validated measures (SIAB) targeting direct symptom criteria with the additional information of measured height and weight of every student.

Contributing to the evidence base, prevalence rates were in accordance with international studies but substantially different to other studies in Germany which indicated much higher prevalences.

DSM-5 criteria, including OSFED, led to more specified information about former Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified, reducing prevalences of partial and subthreshold eating disorders.

Although the sample is large (N=1654 students), it was drawn in a single region in Germany and might therefore not be representative for the whole of Europe.

Introduction

Single eating disorder symptoms such as weight control behaviour or binge/purging behaviour are common issues in adolescents associated with functional impairment.1–5 In contrast, full syndrome eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED) are less frequently observed in adolescents, while their impact on physical health, psychiatric comorbidity and mortality is even more severe.6–9

In Germany, there have only been studies carried out with larger samples of adolescents targeting eating disorder symptoms veering towards but not identical to symptom criteria, and not using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria. Most studies used the SCOFF, a five-item self-report scale which accounts for actual symptoms according to DSM-IV/International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition (ICD-10).10 The rating of eating disorder symptoms in adolescents ranges from 19.3% to 21.9% in 11–17-year-old participants.6 11 12 Partial or subthreshold eating disorders were not analysed thus far in Germany, while data for other countries are available. Especially changes in the OSFED in adolescents in Germany according to the DSM-5 have not been investigated up to now.13 14

In contrast, the National Comorbidity Survey Replication for Adolescents showed 12-month prevalences for full syndrome AN of 0.2%, 0.6% for BN and 0.9% for BED.12 This was in accordance with other authors and investigations for community samples in Canada.1 15–17

Many different strategies are used, especially when observing partial and subthreshold/subclinical eating disorders. One strategy implies initially establishing interview-derived DSM-III-R diagnoses. Subsequently, if individuals met fewer criteria, prevalences in subclinical eating disorders are estimated.18 Subclinical AN was calculated with 3.5% and subclinical BN with 3.8%.

Another strategy is based on a hierarchical approach. ‘Full-syndrome’ eating disorder was determined if a participant met all DSM-IV criteria. ‘Partial-syndrome’ was determined if a participant met some of the DSM-IV criteria. Participants with elevated but not clinically significant scores in criteria ratings were determined as those with ‘subclinical eating disorders’.19–21 With this approach, point prevalences from a sample of 259 students aged 17–20 years for full syndrome and partial syndrome AN of 0% and 5.79% for subclinical AN were reported. Full syndrome criteria for BN were met by 0.77%, partial syndrome by 3.47% and subclinical BN by 1.15% of the participants. No participant met criteria for full syndrome or subclinical BED; partial syndrome for BED was met by 0.38%.20

The change from DSM-IV to DSM-5 led to establishing the category of OSFED. These are distinctive eating disorders with a lower threshold in order to reduce the category of former EDNOS. This might also lead to reduced prevalences of partial and subthreshold eating disorders.13 22 23

The main aim of our study was to investigate, for the first time in Germany, adolescent prevalence rates of DSM-5 eating disorders. The analysis should include full syndrome, OSFED and partial and subthreshold eating disorders in a cross-sectional school-based sample using a hierarchical approach with validated measures targeting direct symptom criteria. A second aim was to investigate prevalences of cases with a self-report questionnaire (Eating Disorder Inventory 2 (EDI-2)).

Method

In 2009, the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Centre of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, together with the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany started a project establishing a primary prevention programme for eating disorders (MaiStep) registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00005050). The data were derived from the baseline sample of the evaluation of the programme.

Setting and sampling

In cooperation with the Ministry of Education in Rhineland-Palatinate, 21 schools (7 of each type of secondary school in Rhineland-Palatinate) were contacted. Of these contacted schools, 17 chose to participate and the allocation was not significantly unequally distributed. The participation rate of 81%, according to Galea and Tracy,24 is excellent. From this pool, six schools were randomly assigned and stratified by type of school. The school pool consisted of all types of secondary schools in Rhineland-Palatinate. Owing to the aim of universal prevention before a disorder is likely to develop, all students in grades 7 and 8 were targeted to participate.25

Initially, all students and their parents in grades 7 and 8 were provided with informational material. We then held evening parent meetings to inform parents and acquire written informed consent. Subsequently, students were additionally verbally informed and asked for their written informed consent.

All baseline evaluations were realised over a period of 1 month. Students filled out questionnaires in groups under examination-like conditions to ensure privacy. A psychologist or trained research assistant supervised the completion, answering questions or managing potential distress. To ensure privacy, weight and height was measured individually by trained same-sex psychologists or research assistants in a separate room. If participants did not want to be informed of their weight or height, this information was concealed.

Instruments and measures

Height and weight was measured with audited scales and stadiometers. Body mass index (BMI) and BMI percentiles were calculated according to current guidelines.26 27

The structured interview for anorexia and bulimia nervosa—self report (SIAB-S) was used in questionnaire form to analyse prevalences of eating disorders, OSFED, partial and subclinical eating disorders accordant to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Mental Disorders, DSM-5.28 Owing to overlap of wording, the SIAB-S, which was originally developed for DSM-IV, can also be used for DSM-5 with the exclusion of Unspecified Feeding and Eating Disorders (UFED).29 It has satisfactory to very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.74–0.92), substantial correlations to the interview form at approximately r=0.60 and showed good reliability and validity.28

Measured BMI percentiles <10th centile were used as A-criterion for AN according to ICD-10.13 An algorithm prioritising AN over BN and subsequently over BED was developed for analysing prevalences of threshold disorders. Threshold disorders were then prioritised over OSFED, which were established before partial and subthreshold disorders. All exact criteria are shown in table 1.

The German version of the EDI-2 was used to obtain point prevalences with a widely used self-report scale.30 The subscales of the EDI-2 are used as a standard measure for screening for eating disorders and for eating disorders pathology. They have a good internal consistency and validity.30 31 T values for each participant, based on the manual, were calculated and dichotomised in ‘non-case’ and ‘case’ by the cut-off criteria of a T value ≥60 (individual score lying more than one SD from the mean).

Table 1.

Overview of criteria to be met for each diagnostic category

| Subcategory |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full syndrome | OSFED | Partial syndrome | Subthreshold syndrome | |

| Category | ||||

| AN | All AN criteria must be met according to DSM-5 Body weight <10th BMI centile |

AN criteria B and C must be met according to DSM-5 Body weight <50th BMI centile |

Two AN criteria must be met (cognitive criteria: B and C)* |

All AN criteria must be met on a lower level of severity Body weight <-1 BMI-SDS |

| BN | All BN criteria must be met according to DSM-5 | BN criteria A, B, D and E must be met according to DSM-5 Binge eating and purging behaviour must occur 1–4 times per month |

At least three BN criteria must be met (behavioural criteria: A, B, C)* |

All BN criteria must be met on a lower level of severity/duration |

| BED | All BED criteria must be met according to DSM-5 | BED criteria A, B, D and E must be met according to DSM-5 Binge eating and purging behaviour must occur 1–4 times per month |

At least three BED criteria must be met (behavioural criteria: A, B, D, E)* |

All BED criteria must be met on a lower level of severity/duration |

| PD | Purging behaviour (self-induced vomiting, intake of appetite suppressants or fasting) must occur at least twice per week, no binge eating | |||

*Additional analysis for cognitive/behavioural symptoms only in order to obtain more detailed information.

AN, anorexia nervosa; BED, binge eating disorder; BMI, body mass index; BN, bulimia nervosa; DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fifth Edition; PD, purging disorder; OSFED, Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder; SDS, Standard Deviation Scores.

Sample size

The original sample size was calculated for evaluating the aforementioned programme for prevention of eating disorders. To ensure adequate power for this approach, a sample size of 1800 participants was calculated, resulting in a baseline sample fulfilling criteria for epidemiological research in adolescent eating disorders.32

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, V.21. A p value of <0.05 was set for statistical significance. χ2 Tests were used to assess deviations from expected proportions.33 CIs for prevalences were calculated according to Newcombe with the efficient score method (corrected for continuity).34

Results

Participants

Of the 1775 students who were contacted to participate in the study, 1654 students and their parents gave written informed consent and data were collected at baseline. This led to a participation rate of 93.2%, which, according to the definition of Galea and Tracy,24 is excellent. The mean age was 13.4 years (SD: 0.8). Nine hundred and twenty participants were in grade 7 and 734 participants in grade 8; 873 (52.8%) participants were female. The mean BMI was 20.00 (SD=3.46) and the mean BMI percentile was 55.25 (SD=29.19). Of all participants, 7.2% had BMI percentiles under the 10th BMI centile (58.8% female participants) and 15.2% had BMI percentiles above the 90th BMI centile (58.4% female participants). All sex differences were non-significant, p>0.05.

Main results

Five female participants fulfilled all criteria of AN; five female and one male participant fulfilled all criteria for BN. Five female and three male participants fulfilled all criteria for BED (for percentages, please refer to table 2). As expected, in all OSFED, just as in partial syndrome and subthreshold syndrome, there was a prevalence of female participants, resulting in significant ratio differences between sexes in some domains. Table 2 shows the number and percentage of participants in each group as well as distribution among sexes.

Table 2.

Number and percentage of students meeting syndrome criteria

| Category | Subcategory | Total sample N=1654 |

Percentage of total (in %) | 95% CI incl. continuity correction | Sex ratio (female:male) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN | Full syndrome | 5 | 0.3 | 0.1 to 0.7 | 5:0 |

| Atypical-AN | 58 | 3.6 | 2.7 to 4.5 | 45:13*** | |

| Partial syndrome (meeting only cognitive criteria) | 180 (115) | 10.9 (7.1) | 9.4 to 12.5 (5.8 to 8.3) |

135:45*** (91:24***) | |

| Subthreshold syndrome | 13 | 0.8 | 0.4 to 1.4 | 10:3 | |

| Any syndrome (sum) | 256 | 15.5 | 13.8 to 17.3 | 195:61*** | |

| BN | Full syndrome | 6 | 0.4 | 0.2 to 0.8 | 5:1 |

| BN (low frequency/duration) | 0 | 0 | − | − | |

| Partial syndrome (meeting only behavioural criteria) |

4 (1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1-0.6 (0.1 to 0.6) | 2:2 (0:1) | |

| Subthreshold syndrome | 5 | 0.3 | 0.1 to 0.7 | 3:2 | |

| Any syndrome (sum) | 15 | 0.9 | 0.5 to 1.5 | 10:5 | |

| BED | full syndrome | 8 | 0.5 | 0.2 to 0.9 | 5:3 |

| BED (low frequency/duration) | 0 | 0 | − | − | |

| Partial syndrome (meeting only behavioural criteria) |

34 (24) | 2.1 (1.5) | 1.5-2.9 (1.0 to 2.2) | 30:4*** (21:3**) | |

| Subthreshold syndrome | 3 | 0.2 | 0.1 to 0.5 | 3:0 | |

| Any syndrome (sum of above) | 45 | 2.7 | 2.0 to 3.6 | 38:7*** | |

| PD | Purging disorder | 31 | 1.9 | 1.3 to 2.7 | 22:9* |

| Total eating disorder syndromes | 347 | 21.0 | 19.1 to 23.0 | 265:82*** | |

***p <0.001, **p <0.01, *p <0.05.

AN, anorexia nervosa; BED, binge eating disorder; BN, bulimia nervosa; PD, purging disorder.

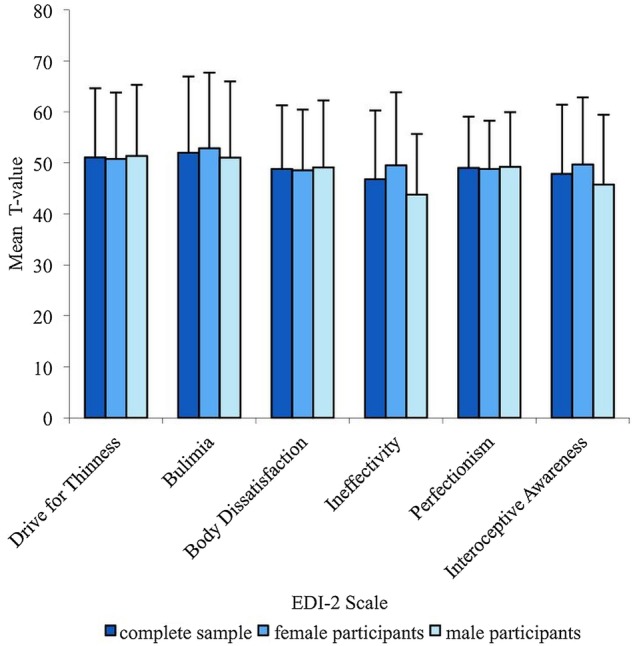

For comparisons between eating disorder syndromes with self-report measures, EDI-2 T-scores were used. The mean value of the scale Drive for Thinness was 51.06 (SD=13.56), for Bulimia 52.00 (SD=14.93), for Body Dissatisfaction 48.81 (SD=12.48), for Ineffectiveness 46.77 (SD=13.52), for Perfectionism 49.01 (SD=10.06) and for Interoceptive Awareness 47.83 (SD=13.56). Figure 1 shows mean values and SDs for the complete sample and is separate for female and male participants.

Figure 1.

Mean values and SDs of the EDI-2 scales for the complete sample and separate for female and male participants. EDI-2, Eating Disorder Inventory 2.

In a second step, prevalences of cases defined by a cut-off-classification of a T value ≥60 on the scales of the EDI-2 were calculated. This led to 349 (21.1%) cases on the scale Drive for Thinness, 306 (18.5%) cases on the scale Bulimia, 288 (17.4%) cases on the scale Body Dissatisfaction, 207 (12.5%) cases on the scale Ineffectiveness, 208 (12.6%) cases on the scale Perfectionism and 269 (16.3%) cases on the scale Interoceptive Awareness. In 2×2 χ² tests with sex by EDI-2 cut-off, females were significantly more likely to score above the cut-off on the Ineffectiveness (χ²=30.68, df=1, p<0.001) and Interoceptive Awareness (χ²=14.33, df=1, p<0.001) scales, whereas male participants were significantly more likely to score above the cut-off on the Perfectionism scale (χ²=7.67, df=1, p<0.01). No sex differences were observed on all other subscales, all p >0.05.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Germany to investigate DSM-5 full syndrome, OSFED, partial syndrome and subthreshold eating disorders in a large population-based sample with validated and augmented (by measuring height and weight) self-report measures.

Prevalences for full syndrome eating disorders established with the SIAB-S were found to be in accordance with corresponding studies in other countries when using DSM-IV/DSM-5 criteria, but divergent to prevalence rates of eating disorder symptoms in German studies, while established cases with the EDI-2 were in accordance with prevalence rates in Germany.6 11 12 15 16 21 35 The previously mentioned studies in Germany used a short self-report questionnaire (SCOFF) with five questions for estimating prevalences according to DSM-IV and ICD-10.13 23 There is literature showing that self-report measures lead to a large number of false positives, whereas other studies showed predictive validity of self-report measures.15 36 37 Especially the SIAB-S, with concisely formulated items, showed good reliability and validity in comparison to interview versions.28 One conclusion for the described substantial differences in prevalence estimates between this study and other studies in Germany could be the usage of a validated measure (SIAB-S) adding objective measures such as height and weight. A second main conclusion is that the use of even short forms of self-report measures with underlying diagnostic criteria could lead to prevalence rates according to expected values.

Until now, OSFED in adolescents have not been investigated in Germany and prevalence rates are thus a new aspect. Atypical AN was slightly pronounced with regard to available research for adolescents. This may be influenced by relatively low numbers of threshold AN with a more rigorous approach using the 10th BMI centile as an underweight criterion, possibly leading to more OSFED. Low numbers of BN (low frequency/limited duration), BED (low frequency/limited duration) and PD may be affected by the younger mean age of the sample in contrast to other studies.14 16 38 As an overall advantage, prevalence rates in atypical AN, BN (low frequency/limited duration), BED (low frequency/limited duration) and PD, as shown in other studies, may reduce the prevalence of former EDNOS, leading to more distinctive information about symptoms.14 38 39

In this study, DSM-5 criteria were used.13 This may have led to an increased prevalence of threshold disorders compared to DSM-IV and is a more progressive approach in regard to ICD-10 criteria and the β version of the upcoming ICD-11.23 38 40 It was found, however, that compared to studies using the SCOFF, prevalence rates of threshold disorders including OSFED were relatively low, providing evidence against overestimation of eating disorders and evidence for categorising former EDNOS more specifically.6 12 38

With the exception of partial AN, with regard to the literature, less pronounced overall prevalences of partial and subthreshold eating disorders were found.18–21 41 42 This may be due to more specific OSFED, which were said to cover some of the previously classified partial and subthreshold cases.38 High prevalences of partial AN with 10.9% depend mainly on high rates of partial AN with cognitive symptoms only (intense fear of weight gain/becoming fat and body image disturbance) with 7.1%. This was in accordance with other studies showing elevated prevalences of partial/subclinical AN when investigating cognitive symptoms and studies showing that body dissatisfaction and weight and shape concerns are common issues in adolescents.3 19 43 The overall projection of partial and subthreshold disorders in regard to threshold disorders underlines a continuum between normal eating behaviour and threshold disorders.

Some authors use single eating disordered behaviour (eg, binge eating with loss of control) as partial/subthreshold criteria while others use hierarchical approaches.20 44 45 Hierarchical approaches mainly define full syndrome (meeting all symptom criteria of an eating disorder), partial (meeting core criteria of an eating disorder without reaching all criteria) and subthreshold/subclinical (showing elevated scores in core criteria without scoring above the cut-off of each symptom) eating disorders.18 44 46 This study also used a hierarchical approach together with a hierarchy between the different eating disorders (AN in ‘superiority’ to BN, which in turn was ‘superior’ to BED). The sample had a mean age of 13.35 years, which led to the expectation of relative large prevalences of AN (any syndrome) with earlier peak onset in ages 14–17 years in comparison to BN and BED with peak onsets of 18 and 16 years.46–48 Hence, the hierarchical approach showed both face validity and logical integrity with prevalences for full criteria for the separate eating disorders according to expected values.

Sex differences in prevalences were most pronounced in full syndrome with 100% female participants with full syndrome AN and projectures for female participants in BN and BED, while partial and subthreshold syndrome led to more balanced proportions. This finding is consistent with the literature showing larger prevalence differences in sex groups for full syndrome eating disorders and more balanced prevalences of single eating disorder symptoms between the sexes.8 41 49 Eating disorder diagnosis may be biased due to female-centric definitions of body image disturbances with the core feature of low body weight, neglecting male-specific characteristics such as muscle dysmorphia and a lack of appropriate instruments for males.50 51 In this analysis, descriptive data of underweight with regard to sex differences showed a small and not significant overhang for female participants. In contrast to other studies, this adds some evidence against the bias hypothesis.5 However, specific body image disturbances in male participants, possibly leading to different body weight/body fat distributions, could have been neglected to some extent due to lack of instruments.51

Nevertheless, a limitation lies in the use of a self-report form. With a second stage of interviewing all participants, symptom criteria could have been compared to more rigorous facts and cross-validated.21 52 On the other hand, interviewing a sample of 1654 participants was not feasible and the use of an augmented version of the SIAB-S with direct symptom criteria and measurement of height and weight was the best compromise of efficacy and validity. Although using a validated measure, there may be a lack in sufficient detection of eating disorders in male participants due to different body image distortions which should be targeted in further research.51 Although the sample size is large, nearly equal balanced for sex and representative with stratification for all types of schools in Germany, it is not representative for German adolescents in regard to a balanced population based on a sample covering the whole age span of adolescence. The sample was drawn from students in south-west Germany and regional differences may exist in other parts of Germany.

In summary, the main issue of this study was to calculate, for the first time, DSM-5 prevalence estimates for adolescents in Germany of full syndrome, OSFED and partial and subthreshold eating disorders with a hierarchical approach. A major concern was overcoming some of the methodological problems of previous studies in Germany using augmented validated measures (SIAB-S) targeting direct symptom criteria and estimating differences in questionnaire measures (EDI-2). Together with prevalence rates for full syndrome eating disorders, calculated as expected in comparison to other international studies and divergent from German studies, there is evidence for a one-step approach which leads to correct classification. Implementing OSFED reduced former EDNOS for a more distinctive symptom classification. However, approaches towards prevalences of eating disorders should include validated measures targeting direct symptom criteria.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Claudia Wachtarz, Ute Spranger, Karin Gellner and Björn Rodday participated in data assessment. Patricia Meinhardt conducted proof reading. The authors are also thankful to all participants.

Footnotes

Contributors: FH and AB conceived the study, designed the analysis and carried out the acquisition of data. FH was responsible for data analysis and drafted the manuscript. VE contributed additional data analysis in accordance with DSM-5 and revised the results. FH, AB and MH revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The MaiStep project was supported through the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs (MSAGD), grant agreement number (632-476701-6.3) and the Ministry of Education, Culture and Research (MBWWK) grant agreement number (9322).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study and the protocol, including the statistical analysis of this study, was approved by the local Commissioner for Data Protection and the Independent Ethics Committee of Rhineland-Palatinate as well as the Department of Education.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:372–80. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay PJ, Mond J, Buttner P et al. Eating disorder behaviors are increasing: findings from two sequential community surveys in South Australia. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e1541 10.1371/journal.pone.0001541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider S, Weiss M, Thiel A et al. Body dissatisfaction in female adolescents: extent and correlates. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:373–84. 10.1007/s00431-012-1897-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley C, Gratwick-Sarll K, Harrison C et al. Sex differences in psychosocial impairment associated with eating disorder features in adolescents: a school-based study. Int J Eat Disord 2015;48:633–40. 10.1002/eat.22396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Oldehinkel AJ et al. Prevalence and severity of DSM-5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescents. Int J Eat Disord 2014;47:610–19. 10.1002/eat.22316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Wille N, Holling H et al. Disordered eating behaviour and attitudes, associated psychopathology and health-related quality of life: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry 2008;17(Suppl 1):82–91. 10.1007/s00787-008-1009-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rojo-Moreno L, Arribas P, Plumed J et al. Prevalence and comorbidity of eating disorders among a community sample of adolescents: 2-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res 2015;227(1):52–7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchison D, Mond J, Slewa-Younan S et al. Sex differences in health-related quality of life impairment associated with eating disorder features: a general population study. Int J Eat Disord 2013;46:375–80. 10.1002/eat.22097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2013;26:543–8. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328365a24f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 1999;319:1467–8. 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Dempfle A, Konrad K et al. Eating disorder symptoms do not just disappear: the implications of adolescent eating-disordered behaviour for body weight and mental health in young adulthood. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry 2015;24(6):675–84. 10.1007/s00787-014-0610-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hölling H, Schlack R. Essstörungen im Jugendalter - Ergebnisse aus dem Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). Ernährungsumschau 2007;9:514–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairweather-Schmidt AK, Wade TD. DSM-5 eating disorders and other specified eating and feeding disorders: is there a meaningful differentiation? Int J Eat Disord 2014;47:524–33. 10.1002/eat.22257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flament MF, Buchholz A, Henderson K et al. Comparative distribution and validity of DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnoses of eating disorders in adolescents from the community. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2015;23:100–10. 10.1002/erv.2339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen KL, Byrne SM, Oddy WH et al. DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 eating disorders in adolescents: prevalence, stability, and psychosocial correlates in a population-based sample of male and female adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 2013;122:720–32. 10.1037/a0034004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preti A, Girolamo Gd, Vilagut G et al. The epidemiology of eating disorders in six European countries: results of the ESEMeD-WMH project. J Psychiatr Res 2009;43:1125–32. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Touchette E, Henegar A, Godart NT et al. Subclinical eating disorders and their comorbidity with mood and anxiety disorders in adolescent girls. Psychiatry Res 2011;185:185–92. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotrufo P, Barretta V, Monteleone P et al. Full-syndrome, partial-syndrome and subclinical eating disorders: an epidemiological study of female students in Southern Italy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998;98:112–15. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotrufo P, Gnisci A, Caputo I. Brief report: psychological characteristics of less severe forms of eating disorders: an epidemiological study among 259 female adolescents. J Adolesc 2005;28:147–54. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H et al. An 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 2009;118:587–97. 10.1037/a0016481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quick V, Berg KC, Bucchianeri MM et al. Identification of eating disorder pathology in college students: a comparison of DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Adv Eat Disord 2014;2:112–24. 10.1080/21662630.2013.869388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edn text rev Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann epidemiol 2007;17:643–53. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opler M, Sodhi D, Zaveri D et al. Primary psychiatric prevention in children and adolescents. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2010;22:220–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Wabitsch M, Kunze D et al. Perzentile für den Body-mass-Index für das Kindes- und Jugendalter unter Heranziehung verschiedener deutscher Stichproben. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2001;149:807–18. 10.1007/s001120170107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herpertz S, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Fichter M et al. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Behandlung der Essstörungen. Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fichter MM, Quadflieg N. Comparing self- and expert rating: a self-report screening version (SIAB-S) of the structured interview for anorexic and bulimic syndromes for DSM-IV and ICD-10 (SIAB-EX). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000;250:175–85. 10.1007/s004060070022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wade TD, O'Shea A. DSM-5 unspecified feeding and eating disorders in adolescents: what do they look like and are they clinically significant? Int J Eat Disord 2015;48:367–74. 10.1002/eat.22303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 1983;2:15–34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thiel A, Jacobi C, Horstmann S et al. Eine deutschsprachige Version des Eating Disorder Inventory EDI-2. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 1997;47:365–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamangar F, Islami F. Sample size calculation for epidemiologic studies: principles and methods. Arch Iran Med 2013;16:295–300. doi:013165/AIM.0010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bortz J. Statistik: Für Human-und Sozialwissenschaftler. Springer-Verlag, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 1998;17:857–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 2007;61:348–58. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Celio AA, Wilfley DE, Crow SJ et al. A comparison of the binge eating scale, questionnaire for eating and weight patterns-revised, and eating disorder examination questionnaire with instructions with the eating disorder examination in the assessment of binge eating disorder and its symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 2004;36:434–44. 10.1002/eat.20057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clausen L, Rosenvinge JH, Friborg O et al. Validating the Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3): a comparison between 561 female eating disorders patients and 878 females from the general population. J Psychopathol Behav 2011;33:101–10. 10.1007/s10862-010-9207-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mancuso SG, Newton JR, Bosanac P et al. Classification of eating disorders: comparison of relative prevalence rates using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Br J Psychiatry 2015;206:519–20. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.143461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caudle H, Pang C, Mancuso S et al. A retrospective study of the impact of DSM-5 on the diagnosis of eating disorders in Victoria, Australia. J Eat Disord 2015;3:35 10.1186/s40337-015-0037-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Adawi S, Bax B, Bryant-Waugh R et al. Revision of ICD–status update on feeding and eating disorders. Adv Eat Disord 2013;1:10–20. 10.1080/21662630.2013.742971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:714–23. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stice E, Ng J, Shaw H. Risk factors and prodromal eating pathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010;51:518–25. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02212.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calzo JP, Sonneville KR, Haines J et al. The development of associations among body mass index, body dissatisfaction, and weight and shape concern in adolescent boys and girls. J Adolescent Health 2012;51:517–23. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Larson NI et al. Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:1004–11. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stice E, Marti CN, Durant S. Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behav Res Ther 2011;49:622–7. 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stice E, Killen JD, Hayward C et al. Age of onset for binge eating and purging during late adolescence: a 4-year survival analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 1998;107:671–5. 10.1037/0021-843X.107.4.671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2006;19:389–94. 10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steinhausen HC, Jensen CM. Time trends in lifetime incidence rates of first-time diagnosed anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa across 16 years in a Danish nationwide psychiatric registry study. Int J Eat Disord 2015;48(7):845–50. 10.1002/eat.22402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Micali N, Ploubidis G, De Stavola B et al. Frequency and patterns of eating disorder symptoms in early adolescence. J Adolesc Health 2014;54:574–81. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchison D, Hay PJ. The epidemiology of eating disorders: genetic, environmental, and societal factors. Clin Epidemiol 2014;6:89–97. 10.2147/CLEP.S40841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitchison D, Mond J. Epidemiology of eating disorders, eating disordered behaviour, and body image disturbance in males: a narrative review. J Eat Disord 2015;3:20 10.1186/s40337-015-0058-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mancilla-Diaz JM, Franco-Paredes K, Vazquez-Arevalo R et al. A two-stage epidemiologic study on prevalence of eating disorders in female university students in Mexico. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2007;15:463–70. 10.1002/erv.796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]