Abstract

Objective

To identify key stakeholder preferences and priorities when considering a national healthcare-associated infection (HAI) surveillance programme through the use of a discrete choice experiment (DCE).

Setting

Australia does not have a national HAI surveillance programme. An online web-based DCE was developed and made available to participants in Australia.

Participants

A sample of 184 purposively selected healthcare workers based on their senior leadership role in infection prevention in Australia.

Primary and secondary outcomes

A DCE requiring respondents to select 1 HAI surveillance programme over another based on 5 different characteristics (or attributes) in repeated hypothetical scenarios. Data were analysed using a mixed logit model to evaluate preferences and identify the relative importance of each attribute.

Results

A total of 122 participants completed the survey (response rate 66%) over a 5-week period. Excluding 22 who mismatched a duplicate choice scenario, analysis was conducted on 100 responses. The key findings included: 72% of stakeholders exhibited a preference for a surveillance programme with continuous mandatory core components (mean coefficient 0.640 (p<0.01)), 65% for a standard surveillance protocol where patient-level data are collected on infected and non-infected patients (mean coefficient 0.641 (p<0.01)), and 92% for hospital-level data that are publicly reported on a website and not associated with financial penalties (mean coefficient 1.663 (p<0.01)).

Conclusions

The use of the DCE has provided a unique insight to key stakeholder priorities when considering a national HAI surveillance programme. The application of a DCE offers a meaningful method to explore and quantify preferences in this setting.

Keywords: surveillance, healthcare associated infection, discrete choice experiment

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first reported use of a discrete choice experiment in the area of healthcare-associated infection surveillance.

The results offer a unique insight into the priorities of stakeholders when considering healthcare-associated infection surveillance programmes.

Not all healthcare-associated infection surveillance stakeholder groups participated.

Background

A healthcare-associated infection (HAI) is an infection that occurs as a result of a healthcare intervention.1 Common HAIs include a bloodstream infection after the insertion of an intravenous catheter, or a wound infection following surgery. Preventing HAIs requires a multimodal approach.2 Although surveillance of HAIs is acknowledged as crucial to HAI prevention,3 Australia is yet to develop a national HAI programme, and existing State and Territory programmes are known to have broad variation of practices and a lack of agreement in identifying HAIs.4 5

There are many stakeholders in HAI surveillance, these include clinicians, hospital executives, governing and regulatory bodies, funders and of course consumers. Ideally data should be used by clinicians to drive infection prevention efforts and reduce the incidence of HAIs.6 Data have also been used to measure hospital performance and, despite a lack of evidence as a driver to reduce infection, hospitals have been financially penalised based on these data.7 8 As such, there are competing demands from a surveillance programme.

A national HAI surveillance programme designed to meet the needs of all stakeholders may not be possible. This study sought to employ discrete choice experiment (DCE) methodology to identify the most important considerations for those involved in HAI surveillance and to assess the degree of convergence or otherwise in the preferences of key stakeholder groups.

DCEs are a quantitative attribute-based survey method, used to elicit preferences for healthcare products, interventions, services, policies or programmes.9–11 Typically, DCEs offer participants a series of hypothetical choice scenarios comprising two or more scenarios that vary according to several key characteristics or attributes, where the participants are required to indicate their preferred scenario.12 A form of stated preference, DCEs are able to provide information on the relative importance of the attributes presented in the hypothetical scenarios.13

DCEs may be considered as more cognitively challenging for participants than other ordinal approaches to preference elicitation, for example, ranking and rating methods.14 However, the main advantages of DCEs are they present choices in a manner that is potentially more relevant to the participants and they provide more information as they generate quantitative data on the strength of preferences and trade-offs, and the probability of take up.9 13

Extensively used in health economics, DCEs have recently been used to assist in developing priority setting frameworks and clinical decision-making.10 In public health settings, DCEs have been used for priority setting frameworks where decision makers are required to manage competing demands with limited resources.15–17 DCEs have also been used to predict uptake of new policies or programmes.18

The main objective of the study was to identify key stakeholder preferences for a national surveillance programme. This will provide crucial information on potential acceptance of a surveillance programme, and provide insight into how stakeholders consider certain elements of surveillance. These data will be vital for informing the future design and implementation of a national HAI surveillance programme in Australia.

Methods

Identification of attributes and levels

There are several key stages in the development of a DCE. The first step in the construction of a DCE is the identification of attributes and levels of the intervention being valued. The chosen attributes and their respective levels are the key factors that will influence the choice of one surveillance programme over another.14 Hence, it is important that the chosen attributes and levels for the DCE are realistic and salient to the participants within the context in which the DCE is being applied.9 11 19

To identify the attributes and levels, we used two methods commonly described in the literature.11 First, a review of the literature was undertaken which identified key articles describing health-related surveillance systems and their attributes.20–22 Second, seven semistructured interviews were conducted with experts in HAI surveillance. Participants were purposively selected because of their expertise in HAI surveillance and experience in developing, implementing and maintaining large surveillance programmes. Four interviews were with leaders from four different international HAI surveillance programmes, two with leaders of different state surveillance programmes in Australia and one interview with an expert from a national body representing national surveillance policy. Using attributes identified from the literature review, an interview guide was constructed for the purpose of corroborating these attributes or identifying new ones. Content analysis using interpretive description was conducted on the transcripts of the semistructured interviews to identify major themes, which were then compared with the attributes identified in the literature. Themes that did not align with those from the literature were used to construct questions about potential new attributes.

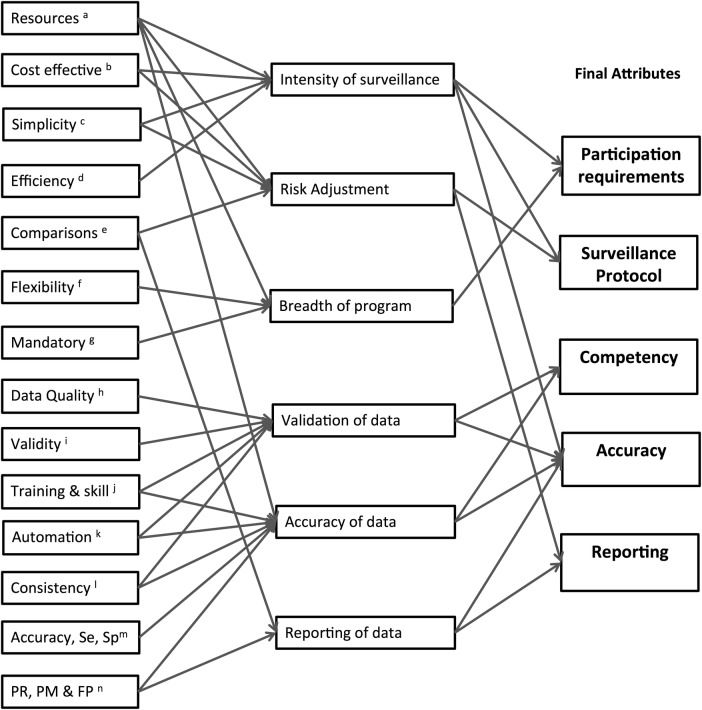

Initially 14 potential attributes were identified. Following review, some of these attributes were collapsed to form six major attributes. Through a series of discussions between the researchers (PLR, LH, JR, GC) the attributes were further refined to five (figure 1). The attributes deemed to be most important in the initial design and implementation of a national HAI programme were: (1) mandatory participation requirements, (2) the type of surveillance protocol, (3) frequency of competency assessments of those collecting data, (4) the overall accuracy of the data and, finally, (5) how the data were to be reported.

Figure 1.

Development of attributes for the discrete choice experiment. (a) Resources required to undertake surveillance. (b) Cost effectiveness of the healthcare-associated infection (HAI) surveillance programme. (c) Simplicity of the surveillance programme, for example, amount of data required, ease of access to data. (d) Efficiency of surveillance processes (commonly related to resources and simplicity). (e) Comparisons of HAI data with other like facilities or a benchmark. (f) Flexibility of the programme. For example, is it able to be tailored to meet individual needs, does it require all infections or is it targeted? (g) Mandatory components required for participation. (h) Data quality such as completeness and sense, and related to validity, accuracy and skill of data collectors. (i) Validity of the data, related to quality, accuracy and skill of data collectors. (j) Training and skill of those involved in collecting, analysing and reporting data. Is there a formal training programme, are skills assessed? (k) Automation of surveillance, for example, electronic data systems, automated surveillance programmes. (l) Consistency of surveillance, for example, consistent methods applied, definitions, analysis, risk adjustment. Related to training and skill of those involved in surveillance. (m) Accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the surveillance programme identified through formal studies. (n) Public reporting, performance measures and financial penalties associated with HAI data. This relates to how data are used.

The levels for each attribute were selected based on a number of considerations. In accordance with best practice guidance for the design and conduct of DCEs in healthcare, they needed to be plausible, actionable and provide a range of options without being too extreme.23 The final levels selected largely reflected a variety of current practices from existing international and local, state-based surveillance programmes. The final attributes and levels are described in more detail in box 1.

Box 1. Final attributes and levels for the discrete choice experiment.

Participation requirements (mandatory)

Targeted 12 months/other 3 months—continuous 12 months targeted surveillance on specified healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) with choice of others for minimum 3 months/year.

Targeted 3 months/other 3 months—minimum 3 months targeted surveillance on specified HAIs with choice of others for minimum 3 months/year.

Complete choice 3 months—minimum 3 months surveillance on your own choice of HAIs.

Surveillance protocol

Light protocol—patient-level data on infected patients only, and aggregated numbers of denominator is collected. Fewer resources required. Does not allow for risk adjustment of HAI rates. Limited ability to compare data externally.

Standard protocol—patient-level data are collected on infected and non-infected patients. More resources required. Allows for risk adjustment of HAI rates. Good ability to compare data externally.

Competency

After the initial surveillance training, surveillance staff are required to undergo regular assessment to ensure skills are maintained.

Every data submission period (eg, quarterly)—supports high consistency of surveillance processes.

Annually—supports reasonable consistency of surveillance processes.

Every 2 years—does not support high consistency of surveillance processes.

Accuracy

It is unlikely that all data will be completely accurate all the time. In general terms there will be an error margin with the HAI rates.

Very accurate—approximately 1–5% error range

Reasonably accurate—approximately 6–10% error range

Less accurate—approximately 11–15% error range

Reporting

The reporting of HAI rates and their use as a performance measure associated with financial penalties for the hospital within a national surveillance programme.

Public with no penalty—data publicly reported on website and not associated with financial penalties.

Public and with penalty—data publicly reported on website and associated with financial penalties

Not public but with penalty—data not publicly reported but are associated with financial penalties.

Not public and with no penalty—data not publicly reported and not associated with financial penalties.

Experimental design

The five attributes and their corresponding levels resulted in 216 profiles (=33×41×21), and a total of 23 220 possible pair wise choice scenarios (=(216×215)/2). A D-efficient design (NGENE Manual 1.1.1 [computer program]. Choice Metrics, 2012)24 with no prior parameters information (which minimise the Dz-error) was used to reduce the number of choice scenarios into a more pragmatic number of 24 choice scenarios for presentation using the Ngene V.1.1.2 DCE design software (http://www.choice-metrics.com). Ngene was also employed to divide the resulting DCE design into two blocks, each containing 12 pair wise choice scenarios to reduce the size of the questionnaire presented to participants. In each block, one choice scenario was duplicated to form a test of internal consistency. This resulted in a total of 13 choice scenarios in each block.

The survey

The survey was constructed using an online survey tool (Key Survey [computer program]. MA: Braintree, 2015). Prior to answering the choice questions, participants were required to respond to five Likert scale attitudinal questions regarding HAI surveillance. This was followed by a detailed description of each of the attributes and levels (box 1). A sample choice scenario was then presented.

A hypothetical scenario was presented which informed the participants a mandatory national HAI surveillance programme was to be implemented, and assuming their existing level of resourcing, they were requested to indicate which of the two surveillance programmes presented they would consider most beneficial to their existing infection prevention programme (table 1).

Table 1.

Example of a choice scenario

| Attributes | Surveillance programme A |

Surveillance programme B |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation requirements (mandatory) | Targeted 12 months/other 3 months | Complete choice 3 months | ||

| Surveillance protocol | Light protocol | Standard protocol | ||

| Competency | Annually | Every 2 years | ||

| Accuracy | Very accurate | Less accurate | ||

| Reporting | Not public but with penalty | Public and with penalty | ||

| Which would you prefer? (tick) | Surveillance programme A | Surveillance programme B | ||

Each choice scenario consisted of the same five attributes but with differing levels. Participants were then randomised into one of two choice blocks. For each choice question, participants were forced to choose one or the other; there was no opt out option available. To assist the participants understanding, a full definition of each attribute and level was made visible using a hover tool.

The final section of the survey comprised five demographic questions regarding age, occupation, years of experience in infection prevention, size of the hospital they worked in (if applicable), State or Territory of employment, and an open general comments question.

The survey was piloted by eight infection prevention experts. Pilot participants indicated they found the DCE easy to understand and complete. All eight correctly matched the duplicate questions.

DCE participants

In total, 184 participants were purposively invited to undertake the DCE over a 5-week period during June and July 2015. These participants were selected because they met at least one of the following criteria, they were:

Coordinators of infection prevention programmes of a network of acute care hospitals or at a single site with >100 beds (there were 147 of these hospitals identified in Australia25);

Infectious diseases physicians or microbiologists attached to infection prevention programmes at large acute care hospitals;

Senior health department employees or advisors whose role influences national/state/territory infection prevention policy;

Key stakeholders on national representative committees involved in national HAI surveillance initiatives;

Considered by the research team (PLR and LH) to be opinion leaders in infection prevention in Australia.

Potential participants identified included 146 attached to acute care hospitals, and another 38 non-hospital-based stakeholders. Potential participants received a personalised email inviting them to undertake the survey.

Data analysis

The DCE data were analysed using a random utility model,26 which could be specified empirically as:

where Uitj is the utility individual i derives from choosing alternative j in choice scenario t, xitj is a vector of explanatory variables (ie, observed attributes), βi is a vector of coefficients reflecting the desirability of the attributes, and εitj is a random error. Conditional on βi, it is assumed that εitj is independent and identically distributed extreme value type 1.

The conditional logit model is a classical method to estimate the utility function.14 However, it assumes that all respondents have the homogeneous preference for the attributes (ie, βi=β). Allowing for the potential preference heterogeneity among respondents, the mixed logit (MIXL) model has gained popularity recently.27–29 The MIXL model estimates both the mean and distribution for each attribute level (ie, βi=β+ηi, ηi is a vector of individual-specific deviations from the mean). In this study, it was assumed that all coefficients of attribute levels are random with normal distribution. The Akaike information criterion was used to compare the overall fit of DCE models. Data were analysed using Stata, V.13 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

A total of 122 completed responses were received over a 5-week period (response rate 66%). Of the 122 respondents, 98 (79%) were clinicians (infection prevention nurses, infectious diseases physician and microbiologists), and others were health department representatives or had acted in a health department advisory role. There was proportionate representation from all State and Territories, 76% had >10 years experience in infection prevention and 66% were aged over 50 years. Of the 93 respondents whose primary employment was in a hospital, 43 (46%) worked in a hospital with >400 beds. Further details of respondent characteristics are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Respondent characteristics

| Characteristic | Percent (n=122) |

|---|---|

| Age bracket | |

| <30 | 0.8 |

| 30–39 | 9.0 |

| 40–49 | 24.6 |

| 50–59 | 46.7 |

| >59 | 18.9 |

| Occupation | |

| Health department representative | 10.7 |

| Infection prevention nurse | 65.6 |

| Infectious diseases physician | 13.1 |

| Other | 10.7 |

| Years experience in infection prevention | |

| <5 | 4.9 |

| 5–10 | 17.2 |

| 11–15 | 27.9 |

| 16–20 | 19.7 |

| >20 | 27.9 |

| NA | 2.5 |

| Number of acute beds | |

| <100 | 2.5 |

| 100–199 | 13.1 |

| 200–400 | 25.4 |

| >400 | 35.3 |

| NA | 23.8 |

| State or Territory | |

| Australian Capital or Northern Territory | 4.9 |

| New South Wales | 27.1 |

| Queensland | 17.2 |

| South Australia | 7.4 |

| Tasmania | 5.7 |

| Victoria | 27.9 |

| Western Australia | 9.8 |

NA, not applicable.

A total of 22 (18%) respondents mismatched the duplicate choice scenario. Analysis of the DCE output was undertaken on the full data set (with mismatches) and the data set with the mismatches excluded. The results of both data sets were very similar; however, it was decided to present results excluding the mismatched respondents on the basis that it could not be assumed that these respondents fully understood the DCE, providing a useable response rate of n=100 for data analysis (see online supplementary table S1 for results on full data set).

bmjopen-2016-011397supp_tables.pdf (468.8KB, pdf)

Results of the MIXL estimates are presented in table 3. It can be seen that all attributes were found to have a statistically significant influence on the preferences for a HAI surveillance programme.

Table 3.

Mixed logit estimates for sample excluding participants who mismatched duplicate question

| Mean coefficient |

SD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute | Level | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE |

| Participation requirements (mandatory) | Targeted 12 months/other 3 months | 0.640** | 0.198 | 1.083** | 0.268 |

| Targeted 3 months/other 3 months | 0.331* | 0.158 | 0.619* | 0.281 | |

| Complete choice 3 months | Reference | ||||

| Surveillance protocol | Standard protocol | 0.641** | 0.204 | 1.698** | 0.240 |

| Light protocol | Reference | ||||

| Competency | Every data submission period | 0.546** | 0.202 | 1.325** | 0.243 |

| Annually | 0.778** | 0.170 | 0.044 | 0.367 | |

| Every 2 years | Reference | ||||

| Accuracy | Very accurate | 1.132** | 0.204 | 1.031** | 0.229 |

| Reasonably accurate | 0.977** | 0.201 | 0.754** | 0.260 | |

| Less accurate | Reference | ||||

| Reporting | Public with no penalty | 1.663** | 0.277 | 1.163** | 0.274 |

| Not public but with penalty | 0.467* | 0.194 | 0.971** | 0.337 | |

| Not public and with no penalty | 0.725** | 0.232 | 1.453** | 0.258 | |

| Public and with penalty | Reference | ||||

| N | 100 | ||||

| Observations | 2400 | ||||

**p<0.01, *p<0.05.

Log likelihood −674.968.

All attributes were dummy coded.

The results identify key stakeholders strongest preferences were for a surveillance programme that has:

A mandated continuous targeted surveillance on specified HAIs with choice of others for a minimum 3 months/year (followed by minimum 3 months targeted surveillance on specified HAIs with choice of others for minimum 3 months/year);

The standard surveillance protocol where patient-level data are collected on infected and non-infected patients;

Annual competency assessments of data collectors (followed by competency assessments every data submission period);

Very accurate data (followed closely by reasonably accurate data); and

Hospital-level data publicly reported on a website and not associated with financial penalties (followed by hospital-level data not publicly reported and not associated with financial penalties).

The statistical significance of the SD coefficients for all but one of the attribute levels (annual competency) confirms the existence of preference heterogeneity for the majority of the attributes. As all coefficients for attribute levels are assumed to be normally distributed, the MIXL estimates relating to the mean coefficient and SD for each attribute level were used to calculate the distribution of preference heterogeneity.30 For example, the coefficient (SD) for the level of targeted 12-month with choice of 3-month surveillance is 0.640 (1.083) indicates 72% of the respondents exhibited a preference for targeted 12 months with choice of 3-month surveillance over a complete choice of surveillance for 3 months. Similarly 65% of respondents had a preference for standard protocol over light, and 86% preferring very accurate data over less accurate and 92% demonstrated a preference for data to be reported public with no penalty over publicly reported with penalty.

Subgroup analyses were conducted using conditional logit model and reported in online supplementary tables S2a and S2b. However, owing to the small sample size in the subgroups, the results should be interpreted with caution. One interesting finding worth highlighting here is that when occupation was divided into clinician and non-clinician, it was found that clinicians preferred very accurate data (p<0.01), non-clinicians preferred mostly accurate data (p<0.05; full results included in online supplementary tables S2a and S2b).

Discussion

This novel application of a DCE has identified the preferences of key stakeholders for a national HAI surveillance programme.

This study indicates key stakeholder preference for a national HAI surveillance programme that has mandatory continuous surveillance on targeted infections with an option to choose surveillance in other areas, a protocol that facilitates risk adjustment for meaningful comparisons, and annual competency assessments of those who undertake the surveillance. The preference is for HAI data to be highly accurate and publicly reported, but not to be associated with any financial penalties.

A surprising result was the preference for annual competency assessments over the more frequent every data submission (quarterly). One explanation may be that competency assessments every data submission may have been considered too resource intensive when compared against an annual assessment.

There are several important points in this study. First, the DCE was constructed based on the findings from a literature review and a series of semistructured interviews with experts in HAI surveillance. This means that the attributes and levels were relevant and meaningful to participants. Second, an attractive feature of a DCE is its ability to provide information about the acceptability (or otherwise) of different characteristics of programmes not yet available in practice.31 This is a crucial point, particularly when considering issues around implementation. Third, the results provide a unique insight into HAI surveillance issues not previously demonstrated in Australia. This study provides evidence identifying the specific characteristics of a HAI surveillance programme that are acceptable to key stakeholders, which, if they are included in a national programme, will increase the likelihood of successful implementation. And finally, given the multimodal approach to infection prevention, and the competing interests of multiple stakeholders, we suggest that DCEs have the potential to clearly identify priority frameworks in this setting given competing demands and limited resources.

A potential limitation of DCEs is that there is some evidence to indicate that respondents tend to make their choices on the basis of familiarity, that is, they tend to express a preference for the status quo,32 and this may explain some of the preference choices observed in this study. Twenty-two respondents mismatched the duplicate choice scenario. This could mean that some found the DCE challenging; alternatively, it may be that some respondents changed their preferences as they worked through the DCE. Nevertheless, analyses of data both with and without these mismatches indicated very similar results and did not alter the main findings. Another potential limitation is that the not all key stakeholder groups were able to be included in this study for practicality reasons, in particular hospital executive and quality and safety staff. However, major strengths of this study are the inclusion of attributes identified through qualitative research methods that are relevant and meaningful, its specific targeting of leaders in infection prevention programmes, the national sample frame, and a high response rate.

Our study is the first application of a discrete choice analysis to identify key stakeholder preferences and priorities for HAI surveillance. Given the multimodal approach to infection prevention, and the competing interests of multiple stakeholders, DCEs have the potential to clearly identify priority frameworks in this setting, where competing demands and limited resources have been clearly demonstrated.33 34

Conclusions

This paper describes the novel application of a DCE to identify stakeholder preferences for a national HAI surveillance programme that can be used to inform evidence-based recommendations.

In HAI prevention where there are many key stakeholders from a variety of settings with differing and competing priorities, the application of a DCE has the potential to explore and quantify preferences in this setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance from the infection prevention-related experts who undertook the discrete choice experiment, the international and national leaders who participated in the semistructured interviews, the Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Health Care, the State and Territory Health Department representatives, and the Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control. PLR acknowledges the Rosemary Norman Foundation and the Nurses Memorial Centre through the award of the ‘Babe’ Norman Scholarship for PhD studies.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Philip Russo at @PLR_aus

Contributors: PLR conceived, designed, administered and analysed the study and drafted and prepared the manuscript. GC and JR provided expertise in the experiment design and analysis and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. ACC, MR and NG advised on study design and analysis and manuscript preparation. LH supervised study design, administration, analysis and manuscript preparation.

Funding: PLR receives minor support from NHMRC funded Centre of Research Excellence in Reducing Healthcare Associated Infection (Grant 1030103). GC is a research fellow in health economics funded by a Beat Cancer Project Hospital Package titled ‘Flinders Centre for Gastrointestinal Cancer Prevention’. ACC is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (Grant 1068732). NG is funded by a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (Grant 1059565). LH receives funding from the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Reducing Healthcare Associated Infection (Grant 1030103).

Competing interests: PLR is a member of the Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Health Care, Healthcare Associated Infection Advisory Committee, an Executive Council Member of the Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control and previously Operations Director at the VICNISS Coordinating Centre. MR is the Director of the VICNISS Coordinating Centre, which established and runs the State healthcare infection surveillance programme in Victoria. He is Chair of the Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Health Care, Healthcare Associated Infection Advisory Committee. NG provides advice to the Centre for Healthcare Related Infection Surveillance and Prevention (CHRISP), QLD Health, and is a member of the Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Health Care, Healthcare Associated Infection Advisory Committee. LH was previously the Manager of Epidemiology and Research at CHRISP, and is Chair of the Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Health Care, Healthcare Associated Infection Technical Working Group.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 1500000304).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare. Commonwealth of Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell BG, Gardner A. Addressing the need for an infection prevention and control framework that incorporates the role of surveillance: a discussion paper. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:533–42. 10.1111/jan.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheckler WE, Brimhall D, Buck AS et al. Requirements for infrastructure and essential activities of infection control and epidemiology in hospitals: a consensus panel report. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1998;19:114–24. 10.2307/30142002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo PL, Barnett AG, Cheng AC et al. Differences in identifying healthcare associated infections using clinical vignettes and the influence of respondent characteristics: a cross-sectional survey of Australian infection prevention staff. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2015;4:29 10.1186/s13756-015-0070-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo PL, Cheng AC, Richards M et al. Variation in health care-associated infection surveillance practices in Australia. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:773–5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haley RW. The scientific basis for using surveillance and risk factor data to reduce nosocomial infection rates. J Hosp Infect 1995;30(Suppl):3–14. 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90001-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee TB, Montgomery OG, Marx J et al. Recommended practices for surveillance: Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), Inc. Am J Infect Control 2007;35:427–40. 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Runnegar N. What proportion of healthcare-associated bloodstream infections (HA-BSI) are preventable and what does this tell us about the likely impact of financial disincentives on HA-BSI rates? Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control 2014 Conference 23–26 November 2014; Adelaide, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. How to conduct a discrete choice experiment for health workforce recruitment and retention in remote and rural areas: a user guide with case studies. 2012. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/DCE_UserGuide_WEB.pdf (accessed 26 Jun 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ 2012;21:145–72. 10.1002/hec.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user's guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:661–77. 10.2165/00019053-200826080-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan M, Gerard K, Currie G. Using discrete choice experiments in health economics. In: Jones AM, ed. The Elgar companion to health economics. 2nd edn Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2012:437–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louviere J, Hensher DA, Swait J. Stated choice methods: analysis and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. The Netherlands: Springer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baltussen R, Stolk E, Chisholm D et al. Towards a multi-criteria approach for priority setting: an application to Ghana. Health Econ 2006;15:689–96. 10.1002/hec.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baltussen R, ten Asbroek AH, Koolman X et al. Priority setting using multiple criteria: should a lung health programme be implemented in Nepal? Health Policy Plan 2007;22:178–85. 10.1093/heapol/czm010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green C, Gerard K. Exploring the social value of health-care interventions: a stated preference discrete choice experiment. Health Econ 2009;18:951–76. 10.1002/hec.1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall J, Kenny P, King M et al. Using stated preference discrete choice modelling to evaluate the introduction of varicella vaccination. Health Econ 2002;11:457–65. 10.1002/hec.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Discrete choice experiments in a Nutshell. In: Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M, eds. Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. Vol 11 The Netherlands: Springer, 2008:13–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drewe JA, Hoinville LJ, Cook AJ et al. Evaluation of animal and public health surveillance systems: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:575–90. 10.1017/S0950268811002160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gastmeier P, Sohr D, Schwab F et al. Ten years of KISS: the most important requirements for success. J Hosp Infect 2008;70(Suppl 1):11–16. 10.1016/S0195-6701(08)60005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM et al. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan M. A role for conjoint analysis in technology assessment in health care? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1999;15:443–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reed Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health 2013;16:3–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Health Performance Authority. MyHospitals 2015. http://www.myhospitals.gov.au (accessed 9 Mar 2014).

- 26.McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P, ed. Frontiers in econometrics. New York: Academic Press, 1973:105–42. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S et al. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 2014;32:883–902. 10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hole AR. Fitting mixed logit models by using maximum simulated likelihood. Stata J 2007;7:388–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFadden D, Train K. Mixed MNL models for discrete response. J Appl Econ 2000;15:447–70. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bessen T, Chen G, Street J et al. What sort of follow-up services would Australian breast cancer survivors prefer if we could no longer offer long-term specialist-based care? A discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer 2014;110:859–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ratcliffe J, Laver K, Couzner L et al. Health economics and geriatrics: challenges and opportunities. In: Atwood C, ed. Geriatrics 2012:209–34. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salkeld G, Ryan M, Short L. The veil of experience: do consumers prefer what they know best? Health Econ 2000;9:267–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haustein T, Gastmeier P, Holmes A et al. Use of benchmarking and public reporting for infection control in four high-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:471–81. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70315-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zingg W, Holmes A, Dettenkofer M et al. , Systematic review and evidence-based guidance on organization of hospital infection control programmes (SIGHT) study group. Hospital organisation, management, and structure for prevention of health-care-associated infection: a systematic review and expert consensus. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:212–24. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70854-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011397supp_tables.pdf (468.8KB, pdf)