Abstract

Introduction

Given the sharp rise in opioid prescribing and heightened recognition of opioid addiction and overdose, opioid safety has become a priority. Clinical guidelines on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) for chronic pain consistently recommend routine monitoring and screening for problematic behaviours. Yet, there is no consensus definition regarding what constitutes a problematic behaviour, and recommendations for appropriate management to inform front-line providers, researchers and policymakers are lacking. This creates a barrier to effective guideline implementation. Thus, our objective is to present the protocol for a Delphi study designed to: (1) elicit expert opinion to identify the most important problematic behaviours seen in clinical practice and (2) develop consensus on how these behaviours should be managed in the context of routine clinical care.

Methods/analysis

We will include clinical experts, defined as individuals who provide direct patient care to adults with chronic pain who are on LTOT in an ambulatory setting, and for whom opioid prescribing for chronic non-malignant pain is an area of expertise. The Delphi study will be conducted online in 4 consecutive rounds. Participants will be asked to list problematic behaviours and identify which behaviours are most common and challenging. They will then describe how they would manage the most frequently occurring common and challenging behaviours, rating the importance of each management strategy. Qualitative analysis will be used to categorise behaviours and management strategies, and consensus will be based on a definition established a priori.

Ethics/dissemination

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). This study will generate Delphi-based expert consensus on the management of problematic behaviours that arise in individuals on LTOT, which we will publish and disseminate to appropriate professional societies. Ultimately, our findings will provide guidance to front-line providers, researchers and policymakers.

Keywords: delphi, opioid, chronic pain, analgesics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first study to generate Delphi-based expert consensus on the management of common and challenging behaviours that arise in individuals on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT).

We expect our findings will provide guidance to front-line providers, especially primary care providers who care for the majority of patients with chronic pain on LTOT, in addition to researchers and policymakers. This will represent an important adjunct to existing guidelines that advocate the use of risk mitigation strategies in individuals on LTOT, but lack clear guidance on how to optimally address problematic behaviours that are detected.

The goal of our purposeful sampling strategy is not to survey a group representative of the broader population, but rather to include participants who have the expertise necessary to optimally respond to the questions raised. However, the strategies advocated by these experts may not be appropriate for all practice settings.

Introduction

Long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) is commonly prescribed for individuals with chronic pain.1 Given the sharp rise in opioid prescribing over the past 20 years, and heightened recognition of LTOT risk including addiction and overdose, opioid safety has become a priority.2

Safe opioid prescribing requires careful attention to patient behaviour while on LTOT. Problematic behaviours that arise in individuals on LTOT are common.3 These behaviours are often referred to as ‘aberrant drug-related behaviours’ or ‘opioid misuse behaviours’. Many such behaviours have been described in the literature and include running out of medication early, requesting dose escalation, using multiple prescribers, demonstrating angry or aggressive behaviour related to opioids, and engaging in concurrent risky substance use (eg, cocaine use).4 The reported prevalence of these problematic behaviours among individuals on LTOT varies widely. For example, one review found an average prevalence of 11.5%;3 however, rates are higher among individuals with histories of substance use disorders and mental illness.5

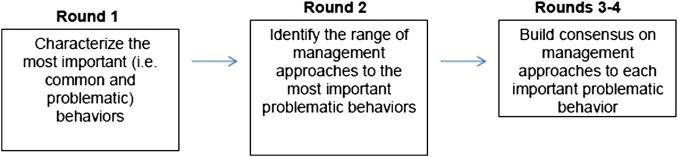

Figure 1.

Delphi round overview.

Despite the commonness of these behaviours in clinical practice, front-line providers receive little training or guidance on how to respond to them. It can be complicated—each behaviour has its own differential diagnosis,6 but assigning a diagnosis is often not straightforward. For example, running out of medication early may be a result of lack of understanding of medication directions, low health literacy/numeracy, poorly treated pain, limited coping skills, taking the medication to treat non-pain symptoms such as depression, an opioid use disorder, or diversion or a combination of multiples of these factors. Distinguishing among these possibilities and managing the patient while doing so can be extremely challenging. This can lead to provider frustration and even burnout.7 8

It is essential to safe and effective patient care that providers are well prepared to address these behaviours. Therefore, the management of problematic behaviours among individuals on LTOT is an area in which front-line providers need urgent guidance. However, the literature in this area is scant. Existing studies focus on prevention and identification of problematic behaviours. For example, numerous studies have examined the use of screening tools prior to initiation of LTOT to identify individuals who are at highest risk for developing problematic behaviours.9 Additionally, widely cited opioid guidelines (eg, American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM), Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense, Centers for Disease Control) advocate routine monitoring of individuals on LTOT using urine drug testing to screen for substance use, use of practitioner database monitoring programmes to identify individuals who are accessing multiple prescribers, and monitoring for other concerning behaviours.10 Even with urine drug test monitoring, providers often fail to respond to abnormal results.11 These areas of enquiry are all important, but do not address the management of problematic behaviours when they arise. Further, we argue that gaps in knowledge about how to respond to these behaviours are a barrier to optimal implementation of opioid guidelines. When providers follow the guidelines, they often uncover concerning behaviours, but may not know what to do next.

Importantly, there is no consensus definition of what constitutes a problematic behaviour. While prior studies list these concerning behaviours,4 12 none defines them precisely, or indicates which behaviours are the most important in clinical practice. Foundational work defining and understanding such behaviours is critical for front-line clinicians, researchers and policymakers alike and an important and needed step in identifying these behaviours in practice, conducting studies that investigate how often such behaviours occur, and developing and implementing strategies and policies to address them.

Study objectives

The objectives of this study are to use the Delphi method to accomplish two important goals. First, we will elicit expert opinion to identify the most important problematic behaviours seen in clinical practice. Then we will develop consensus on how these behaviours should be managed in the context of routine clinical care. Here, we will present our study protocol.

Methods/analysis

The Delphi method is a particularly useful technique when the evidence base in an area falls short of the clinical need.13 This method is widely accepted for gaining consensus on a wide range of issues and is particularly well suited for extracting variables or ideas from a diverse group of experts. The method also allows for expert input to be refined into a set of variables based on pure expert consensus that is untainted by social pressure or authority figures.14 Concerning behaviours among individuals on LTOT are very common, and providers and researchers would benefit from cohesive guidance outlining how to define and manage these behaviours. The Delphi method is useful in this situation because it captures and guides the input efforts of an expert panel towards consensus.15 It stands to reason that front-line providers, especially those with expertise in chronic pain and LTOT, have substantial knowledge and experience on which to draw. The Delphi method allows us to harness this knowledge and experience and, through a series of carefully constructed rounds, build consensus.13

In a Delphi study, the rounds often begin with open-ended brainstorming to identify the concepts on which subsequent closed-ended rounds will focus. These closed-ended rounds typically provide participants with feedback about how they and the group as a whole responded to questions in prior rounds. Participants are also allowed the opportunity to change their responses on the basis of this feedback.

The Delphi method has the advantage of bringing experts from diverse geographic locations and practice settings together anonymously. Since individual participants do not interact with each other, but rather receive anonymous feedback on their peers' responses, the opportunity for a few individuals' opinions to dominate the results is minimised. Additionally, in our case, we will conduct the Delphi process electronically using a web-based platform. This speeds data collection, thereby reducing time between rounds.

Oversight committee

The study authors will serve as an oversight committee, which we named Collaboration and Resources for Pain and Opioid Opinion Leaders (CARPOOL). CARPOOL originated organically through interaction over common interests in promoting safe opioid prescribing practices, initially at the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse (AMERSA) conference. Most of the study authors (JSM, SA, WCB, JML, JLS, EJE) are internists with expertise in chronic pain, LTOT, opioid risk mitigation and addiction, who are active in clinical care and research in this area, particularly as it relates to vulnerable populations including Veterans, HIV-infected patients, those with comorbid pain and substance use disorders, and those who are socially disadvantaged. Additionally, the study's clinicians are collectively based at five different academic institutions in five different states. One study author (JP) is a Delphi expert who served as a methodologist on several similar studies.

Prior to beginning our work on this project, we conducted reviews of existing opioid guidelines and relevant literature. We meet regularly depending on the project's needs on a monthly to quarterly basis by phone and email to discuss this project. We have developed the protocol described here, and we will also develop and pilot test all study questionnaires and refine as necessary. Two of the authors (JSM and SRY) will lead the data collection and initial analysis. Results will be discussed with the group at regular meetings and analyses will be revised when needed.

Selection of Delphi participants and inclusion criteria

Delphi studies typically use a purposive sampling strategy. The goal of purposeful sampling is not to survey a group representative of the broader population, but rather to include participants who have the expertise necessary to optimally respond to the questions raised.16 In this case, we are interested in identifying chronic pain experts. We were particularly interested in chronic pain experts who would have significant experience treating patients with chronic pain in primary care settings, as we want the guidance generated from this study to be useful to front-line primary care providers. Therefore, we decided to approach the following groups:

Members of the AAPM. AAPM members include specialists in anaesthesia/pain medicine, internal medicine, neurology/pain medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation/pain medicine, and psychiatry/pain medicine.

Members of the Society of General Internal Medicine who participate in the Pain Medicine Interest Group or the Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drug Use Interest Groups.

Veterans Administration (VA) ‘Pain Points of Contact’, who are experts in pain at VA medical centres throughout the USA. We included individuals who would be able to prescribe opioids (eg, MDs), or those who commonly influence prescribing decisions (eg, pharmacists, nurse specialists).

Safe and Competent Opioid Prescribing Education (SCOPE) of Pain trainers. SCOPE is a well-regarded Risk Evaluation and Monitoring Strategy (REMS) course for extended-release and long-acting opioids that uses local collaborators who are primary care providers, along with SCOPE developers at Boston University, to train front-line opioid prescribers around the country.17

All individuals in 1–4 above were invited to participate. These groups are enriched with pain experts. However, we developed additional inclusion criteria to ensure that only individuals with sufficient pain expertise will participate. Prior to beginning the first round, participants will be asked whether they provide direct patient care to adults with chronic pain who are on LTOT (>3 months) in an ambulatory setting, and whether opioid prescribing for chronic non-malignant pain is one of their areas of expertise (eg, have taught others on this topic; published on this topic or are considered a resource for other clinicians on this topic). Participants must answer yes to these two questions in order to proceed with enrolment.

Delphi process

All surveys are electronic and will be developed in Qualtrics software 2015 (Provo, Utah, USA). An email will be sent with a link to the survey for each round and a completion deadline in 3 weeks. Weekly reminder emails will be sent. If insufficient participation has occurred by 3 weeks, additional time may be given to solicit additional responses.

The study will be conducted in four rounds. The figure provides an overview of the rounds, described in detail below.

Round 1

Aim

Since there is no consensus on which problematic behaviours among individuals on LTOT are most important, round 1 will be a traditional open-ended brainstorming round. Relative to this study, we decided that the behaviours that are most important are those that either occur often in clinical practice, or are particularly challenging to manage.

Data collection

We will ask participants the following open-ended question: ‘List all behaviours and other concerning signs you would consider to be problematic among patients taking long-term opioids (>3 months). Note: problematic behaviours may also be referred to as opioid misuse behaviours or aberrant drug-related behaviours’. Participants will be prompted to enter a free-text response. The participant will then be given a list of the behaviours they just entered, and asked which two are the most common in clinical practice, and which two are the most challenging to manage in clinical practice.

Data analysis

Using an inductive, thematic approach, we will analyse participants' responses using NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty V.10, 2012). The purpose of this analysis is to categorise all problematic behaviours participants list. While two authors (SRY and JSM) will conduct the analysis, the rest of the CARPOOL team will review the results and provide feedback on the coding scheme. We will also separately determine the common behaviours and the challenging behaviours that were mentioned most often, combine those frequencies, and then select the most frequently mentioned behaviours. We will consider these to be the most important behaviours, and carry these forward to subsequent rounds.

Round 2

Aim

The purpose of round 2 is to elicit the range of management approaches to each of the most important behaviours identified in round 1.

Data collection

Participants who completed the first round will be asked, ‘Please tell us how you would typically manage (behaviour) in individuals on long-term opioid therapy in your clinical practice. Please be as detailed as possible’. Participants will be prompted to enter a free-text response.

Data analysis

Similar to round 1, we will use an inductive, thematic approach to qualitatively analyse these responses, led by two authors (SRY and JSM) with input from the CARPOOL team. For each behaviour, we will determine which responses were listed multiple times.

Round 3

Aim

The purpose of this round is to begin to build consensus on these common responses to each behaviour. Here, we define consensus criteria a priori, which is considered an important mark of rigour in Delphi studies.18

Data collection

Participants in either of the first two rounds will be invited to participate in round 3. We will ask participants to rate the importance of management strategies we identified in the previous round on a scale of 1–9, where 1 is not at all important and 9 is extremely important. For each management strategy, participants will also have an opportunity to clarify or qualify their responses using free text.

Data analysis

The CARPOOL team, led by our Delphi expert (JP), developed the analytic plan based on a review of other relevant studies,19 20 and adaptation to our study question. We will classify responses in the 1–3 range as ‘not important’, 4–6 ‘uncertain’ and 7–9 ‘very important’. We defined disagreement a priori as one-third or more votes in the ‘not important’ range and one-third or more votes in the ‘very important’ range. In the absence of disagreement, there is consensus. If there is consensus, we will evaluate the median value across all participants. If the median is ≥7, the management strategy is important; if it is ≤3, the management strategy is not important, and if it is between 3 and 7, it is uncertain.

Round 4

Aim

This final round will provide us with the opportunity to clarify the results of round 3.

Data collection

Only participants from round 3 will be invited to participate in round 4. If a management strategy for a particular behaviour reached consensus in round 3, we will not present it in round 4. However, if there was disagreement and the strategy did not reach consensus, we will present participants with their response and a summary of their peers' response in the prior round. They will be asked again to rate the importance of the management strategy on the 1–9 scale.

Analysis

The purpose of providing feedback and asking participants to rate the strategy again is to build consensus on questions that did not achieve consensus in round 3. Therefore, round 4 analysis will follow a schema similar to round 3. Strategies that do not achieve consensus in round 4 will not be pursued further.

Sample size

We identified 319 potential Delphi participants from these groups. We will approach all 319, as we expect that many of these individuals will not meet inclusion criteria. Only participants who complete the first round will be allowed to complete the second round. To maximise participation, we will allow participants who complete only the first round, or participants who complete the first and second rounds, to complete the third round. Only participants who complete the third round will be allowed to complete the fourth round.

There is no consensus on the minimum sample size of a Delphi study. Studies with as few as five participants have been published and can be meaningful.13 However, our goal is to have at least 20 participants complete the fourth round to ensure a range of perspectives and experience. Since 70% retention between rounds is considered robust,13 our goal is to have at least 40 participants in the first round, at least 28 participants in the second and third rounds (since both will draw from that original 40), and at least 20 participants in the fourth round.

Retention plan

Several procedural aspects of Delphi studies can improve retention; these include short durations of time between rounds, and clear invitations to participate that emphasise the importance of each individual's contribution.13 In addition, one participant in each round will be randomly selected to receive a $100 Amazon.com gift card. Participants will also be informed that if they complete all four rounds, they will have the option of being acknowledged by name in the final publication.

Ethics

The initial Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval covers the overall study; approval for each round will be submitted separately. Consent to participate is incorporated into round 1 as follows. After the questions establishing inclusion criteria, age 19 or older and willingness to participate, there is a statement that reads, ‘By clicking the forward arrows at the bottom of this screen, you agree to participate as a research participant and that your responses will be used for research purposes’. The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) IRB waived the requirement of further document consent.

Study status and dissemination

Data collection for this study began in March 2015. Rounds 1 and 2 data collection and analysis are complete. We are currently collecting data for round 3. We anticipate that rounds 3 and 4 data collection and analysis will be completed by June 2016.

The results of round 1 were presented at AMERSA's annual conference in November 2015. We plan to submit the main results of the Delphi study for presentation and publication by Spring/Summer 2016. We plan to publish noteworthy findings from individual rounds, such as how consensus was built on the responses to particular behaviours or groups of behaviours. Additionally, we plan to contact the professional organisations from which our study participants were recruited to alert them of the findings, as they are the professional home to many providers (eg, primary care providers, pain specialists) caring for individuals with chronic pain on LTOT.

Discussion

In sum, this study will be the first, to the best of our knowledge, to generate Delphi-based expert consensus on the management of common and challenging behaviours that arise in individuals on LTOT. Ultimately, we expect our findings will provide guidance to front-line providers, especially primary care providers who care for the majority of patients with chronic pain on LTOT, in addition to researchers and policymakers. This will represent an important adjunct to existing guidelines that advocate the use of risk mitigation strategies in individuals on LTOT, which often uncover problematic behaviours but do not provide guidance on how to address them.

After developing and publishing our findings in a consensus document, we plan to evaluate its use in practice. For example, we intend to study the use of this guidance in a multisite trial, and determine patient outcomes such as recurrent problematic behaviours, identification of untreated opioid use disorder, and patient and provider satisfaction.

In addition, implementation considerations such as whether and how front-line primary care clinicians can translate our study's results into practice merit careful consideration. For example, we will investigate barriers and facilitators to adoption of the Delphi's management guidance in the context of busy primary care settings with patients who have multiple comorbidities, providers with differing levels of experience in chronic pain and LTOT, and variable access to resources such as psychiatric and addiction treatment. It will be critical to involve front-line primary care providers in this implementation research. We will also evaluate the impact of our management guidance on successful implementation of existing opioid guidelines. We expect that increased provider guidance for how to handle these complex issues will improve professional satisfaction and patient outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: JSM is the principal investigator. All authors participated in the design of the Delphi protocol by refining the study question and methods, and creating and pilot testing surveys for each round. JSM was responsible for drafting this manuscript, which all authors have read and approved.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH104073 (JSM)) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA027719 (JLS) and K12DA033312 (EJE)).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The initial Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval covers the overall study; approval for each round will be submitted separately.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Frenk SM, Porter KS, Paulozzi LJ. Prescription opioid analgesic use among adults: United States, 1999-2012. NCHS Data Brief 2015;189:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker WC, Fraenkel L, Kerns RD et al. A research agenda for enhancing appropriate opioid prescribing in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1364–7. 10.1007/s11606-013-2422-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J et al. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med 2008;9:444–59. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Meshesha LZ et al. Aberrant drug-related behaviors: unsystematic documentation does not identify prescription drug use disorder. Pain Med 2012;13:1436–43. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01497.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Bangsberg DR et al. Opioid analgesic misuse in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:235–7. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker WC, Merlin JS, Manhapra A et al. Management of patients with issues related to opioid safety, efficacy and/or misuse: a case series from an integrated, interdisciplinary clinic. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2016;11:3 10.1186/s13722-016-0050-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Flores JA et al. Veterans affairs primary care clinicians’ attitudes toward chronic pain and correlates of opioid prescribing rates. Pain Med 2008;9:564–71. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00330.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merlin JS, Turan JM, Herbey I et al. Aberrant drug-related behaviors: a qualitative analysis of medical record documentation in patients referred to an HIV/chronic pain clinic. Pain Med 2014;15:1724–33. 10.1111/pme.12533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: prediction and identification of aberrant drug-related behaviors: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Pain 2009;10:131–46. 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:38–47. 10.7326/0003-4819-160-1-201401070-00732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morasco BJ, Krebs EE, Cavanagh R et al. Treatment changes following aberrant urine drug test results for patients prescribed chronic opioid therapy. J Opioid Manag 2015;11:45–51. 10.5055/jom.2015.0251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portenoy RK. Opioid therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain: a review of the critical issues. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;11:203–17. 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00187-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna HP. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. 10.1002/9781444392029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robison R, Pomeranz JL, Moorhouse M. Proposed application of the Delphi method for expert consensus building within forensic rehabilitation research: a literature review. Rehabil Prof J 19:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasquez-Ramos RA. A Delphi to assess a potential set of items to evaluate participatory ethics in rehabilitation counseling. University of Iowa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs 1997;26:623–30. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alford DP, Zisblatt L, Ng P et al. SCOPE of pain: an evaluation of an opioid risk evaluation and mitigation strategy continuing education program. Pain Med 2015. [epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/pme.12878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khodyakov D, Hempel S, Rubenstein L et al. Conducting online expert panels: a feasibility and experimental replicability study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:174 10.1186/1471-2288-11-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shekelle P. The appropriateness method. Med Decis Making 2004;24:228–31. 10.1177/0272989X04264212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]