Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate anxiety sensitivity (AS) in female Chinese nurses to better understand its characteristics and relationship with nursing stress based on the following hypotheses: (1) experienced nurses have higher AS than newly admitted nurses; and (2) specific nursing stresses are associated with AS after controlling general stress.

Setting

The cross-sectional survey was conducted from May 2014 to June 2015 among female nurses at the provincial and primary care levels in Hunan Province, China.

Participants

Among 793 nurses who volunteered to participate, 745 returned and completed the questionnaires. Eligible participants are healthy female nurses aged 18–55 years and exempt from a history of psychiatric disorder or severe somatic disease and/or a family history of psychiatric disorder.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

AS was assessed by the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3). Anxiety symptoms, general stress and nursing stress were measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) and the Nursing Stress Scale (NSS).

Results

There were significant differences overall and in the three dimensions of AS across nurses of different career stages (all p<0.05). Middle and late career nurses had higher AS than early career nurses (all p<0.05), while no significant difference was found between middle and late career nurses. Conflict with physicians and heavy workload had a significant effect on all aspects of AS, whereas lack of support was related to cognitive AS (all p<0.05).

Conclusions

After years of exposure to stressful events during nursing, experienced female nurses may become more sensitive to anxiety. Middle career stage might be a critical period for psychological intervention targeting on AS. Hospital administrators should make efforts to reduce nurses' workload and improve their professional status. Meanwhile, more social support and appropriate psychological intervention would be beneficial to nurses with higher AS.

Keywords: anxiety sensitivity, nursing stress, anxiety symptoms

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first attempt to investigate anxiety sensitivity among Chinese nurses with high levels of anxiety symptoms.

This study only enrols female nurses to exclude the influences of gender differences on general stress and nursing stress.

The study explores the relationship between nursing stress and anxiety sensitivity across career stages after controlling general stress.

The cross-sectional study could not obtain causal relationship between nursing stress and the development of anxiety sensitivity.

Introduction

In China, the unique characteristics of a profession, poor working conditions, high expectation of patients and severe shortage of healthcare professionals have placed Chinese nurses under great pressure and made them vulnerable to develop mental problems such as anxiety. About 43.4% of Chinese nurses from seven cities had anxiety symptoms, with a higher prevalence than the general population.1 Within Chinese nurses, those with longer years of service were more likely to have anxiety symptoms.2 This common anxiety could affect nurses' physical health and influence the quality of healthcare service they provide to patients.3

One possible factor that makes nurses more vulnerable to anxiety is anxiety sensitivity (AS). AS is considered a trait-like cognitive vulnerability, involving the fear of anxiety and arousal-related body sensations based on the belief that they may have negative physical, psychological or social consequences.4 5 Previous studies have suggested that, compared to individuals with low AS, those with high AS are more likely to become alarmed when facing anxious feelings and arousal responses, and to misinterpret them as harmful, thereby leading to increased anxiety symptoms.5–7

Studies investigating the aetiology of AS have pointed out that AS is relatively stable but malleable in adults.5 8–10 To be more specific, AS may increase when individuals are exposed to stressful events.8 10 These stressful events are usually associated with unpleasant bodily sensations, for instance, general emotional experiences, hearing others express fear of arousal-related sensations, witnessing a catastrophic physical event and so forth. Individuals longitudinally exposed to stressful events become more likely to have high AS because they provide opportunities for the development of erroneous beliefs about arousal-related sensations.11 12 Moreover, certain types of stressful events had different effects on specific aspects of AS. McLaughlin and Hatzenbuehler12 found that health-related stressful events were associated with cognitive and physical AS, whereas family discord was associated with cognitive and social AS.

Chinese nurses are known to frequently experience stressful events at work. These include concerns with infections or injuries, worries about potential medical accidents and associated consequences, intensified nurse–patient relationship, seeing the death and suffering of patients, and so forth,1 which may all predispose individuals to high AS and increase risk of developing anxiety. Previous researches suggested that high AS can be reduced after several sessions of psychological intervention; as a result, the prevalence of anxiety disorder is reduced.13–15 These studies indicated that identifying nurses with high AS and providing them with psychological interventions might improve the mental well-being among Chinese nurses and prevent anxiety disorder at an early stage. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored AS among Chinese nurses, a population with a high prevalence of anxiety symptoms.

Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate AS among Chinese nurses. In this study, we only recruited female Chinese nurses because most of the Chinese nurses are females and we want to remove the effect of gender on stress.16 This study first aimed to investigate the characteristic of AS among female Chinese nurses. Since a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms was reported in nurses with more nursing experience, we hypothesise increased AS in groups of nurses with longer years of service. Moreover, this study explored the relationship between nursing stress and AS. Since general stress may be an important factor affecting AS, the impact of nursing stress on each aspect of AS was examined after controlling for general stress.

Methods

Participants

A cross-sectional survey was implemented in Changsha, central south China from May 2014 to June 2015. Incumbent female nurses were recruited from the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Changsha, Hunan). They were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) healthy female nurses; (2)18–55 years old; and (3) without a history of psychiatric disorder or severe somatic disease or/and had a family history of psychiatric disorder.

In total, among 793 incumbent female Chinese nurses volunteered to participate, 745 returned and completed the questionnaires, with a valid response rate of 93.9% (745/793). They were categorised into three distinct years of service grouping with 331 working as a nurse for less than 5 years (the early career); 282 for 5–15 years (the middle career); and 132 for more than 15 years (the late career).2

Procedure

First, informed consent forms detailing the aim of the study were sent to each unit and explained orally to incumbent nurses; then eligible nurses who agreed to participate provided written consent and completed a sociodemographic form, the Chinese version of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) and the Nursing Stress Scale (NSS).

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

All participants completed a short questionnaire assessing sociodemographic features including age, length of schooling, years of service, marriage status and having children.

Anxiety sensitivity

AS was assessed by the ASI-3.5 The scale is an 18-item self-reported questionnaire composed of three subscales: physical (eg, ‘It scares me when my heart beats rapidly.’), social (eg, ‘It is important for me not to appear nervous.’) and cognitive (eg, ‘It scares me when I am unable to keep my mind on a task.’). Each subscale includes six items. Participants are asked to rate how much they agree or disagree with each item on a five-point Likert scale (0=very little to 4=very much) based on their life experience or how they might feel if these events happen to them when they do not experience these events in daily life. Possible points for the total scale range from 0 to 72. Higher score indicates a higher level of AS. The Chinese version of ASI-3 has great internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0. 95).17 In this study, Cronbach's α coefficients for the subscales of ASI-3 were 0.85 (social), 0.90 (physical) and 0.90 (cognitive).

Anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were measured using the BAI.18 The scale consists of 21 items and respondents are asked to report the extent to which each symptom has bothered them in the past week on a four-point Likert scale (0=not at all to 3=severely). Evidence of anxiety symptoms was based on accepted thresholds on the BAI (greater or equal to 10 on the BAI).19 The Chinese version of BAI has excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0. 95).20 In this study, Cronbach's α coefficient for the total scale was 0.92.

General stress

General stress was evaluated by the PSS-10.21 Participants are required to evaluate the degree to which he/she appraises life events as stressful in the past month on a five-point Likert scale (0=never to 4=very often). Four of the 10 items that were phrased in a positive direction thus were reverse-scored (eg, in the past month, how often have you felt that you were on top of things?). The remaining six items were questions such as ‘In the past month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed?’ or ‘In the past month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?’ Higher scores indicate greater stress. The Chinese version of PSS-10 has acceptable internal reliabilities (Cronbach's α=0.65).22 In this study, Cronbach's α coefficient of the total scale was 0.83.

Nursing stress

Nursing stress was assessed by the NSS.23 The scale consists of 34 items measuring the frequency of 7 stressful situations experienced by hospital nurses. Among the 34 items on the scale, 7 are designed for stressful events related to death and dying patients (eg, listening or talking to a patient about his/her approaching death), 5 for conflict with physicians (eg, criticism by a physician), 3 for inadequate preparation (eg, feeling inadequately prepared to help with the emotional needs of a patient), 3 for lack of staff support (eg, lack of an opportunity to share experiences and feelings with other personnel on the unit), 5 for conflict with other nurses (eg, criticism by a supervisor), 6 for workload (eg, not enough time to complete all of my nursing tasks) and 5 for uncertainty concerning treatment (eg, not knowing what a patient or a patient's family ought to be told about the patient's condition and its treatment). Individuals are required to score on a four-point Likert scale (1=never to 4=very frequently), with a higher score indicating a higher frequency of experiencing occupational stress. The Chinese version of NSS showed good internal reliabilities (Cronbach α=0.91).24 In this study, Cronbach's α coefficient of the total scale was 0.92.

Statistical analysis

All statistical procedures were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences V.19.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive analysis was carried out for sociodemographic variables. χ2 tests and Fisher's exact tests were used to examine whether marital status and having children were different across groups. Pearson's correlations were used to see the relationship between AS and anxiety symptoms. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine if differences in age, years of schooling and AS occurred across groups. The Levene test was conducted for analysis of homogeneity of variances. The Bonferroni tests and Dunnett T3 tests were conducted for post hoc comparison analyses of ANOVA, respectively, when homogeneity of variances were assumed and not assumed. Hierarchical regression analyses were performed to examine the impact of nursing stress subscales on dimensions of ASI-3 among female nurses after controlling for years of service, marital status, having children and general stress. Collinearity between independent variables was conducted on the basis of variance inflation factors and tolerances.25 The controlling variables were entered into the first regression equation followed by the nursing stress subscales into the second. Forced entry was used for all variables. We used a significance threshold of p<0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Information on sociodemographic characteristics grouped by years of service is presented in table 1. There were significant differences in age, marital status and having children across groups (all p<0.001). Overall, the age of nurses ranged from 20 to 55 years. The mean age was 29.75 (SD=6.525) years and the mean length of schooling was 16.07 (SD=0.863) years. More than half of the nurses (58.7%) were married and about half of them (50.7%) have children.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of incumbent nurses grouped by years of service (n=745)

| Career stage |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early (n=331) | Middle (n=282) | Late (n=132) | F or χ2 | |

| Years of age (SD) | 24.66 (2.109) | 30.79 (3.083) | 40.29 (5.525) | 1073.066*** |

| Years of schooling (SD) | 16.03 (0.810) | 16.07 (0.797) | 16.15 (1.095) | 0.889 |

| Marital status (%) | 345.573*** | |||

| Single | 251 (75.8%) | 35 (12.4%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Married | 75 (22.7%) | 239 (84.8%) | 119 (90.2%) | |

| Widowed or divorced | 5 (1.5%) | 8 (2.8%) | 11 (8.3%) | |

| Children (%) | 460.866*** | |||

| Yes | 24 (7.3%) | 226 (80.1%) | 128 (97.0%) | |

| No | 307 (92.7%) | 56 (19.9%) | 4 (3.0%) | |

***p<0.001.

AS and its relationship with anxiety symptoms

In this study, 32.8% nurses had anxiety symptoms, with the mean score of 8.13 (SD=7.784). AS was positively associated with anxiety symptoms (r=0.519, p<0.01). The correlation coefficients of the subscales and anxiety symptoms ranged from 0.412 (social) to 0.526 (cognitive).

Characteristics of AS in nurses grouped by years of service

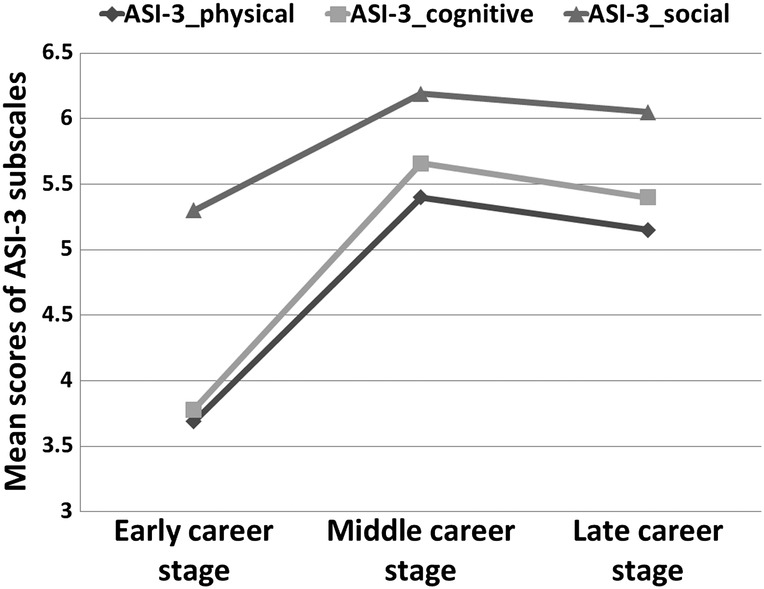

The mean AS score for the entire sample was 15.13 (SD=13.037). All participants had the highest mean score on the social subscale, which was 5.77 (SD=4.581). As shown in table 2, a statistically significant difference was found in the overall AS level by career stages, F=10.225, p<0.001. In addition, there were significant differences of physical, social and cognitive AS across groups. For the physical AS, F=11.631, p<0.001; for the social AS, F=3.222, p<0.05; and for the cognitive AS, F=14.307, p<0.001. In addition, patterns of the physical, social and cognitive AS across nurses with different years of service are shown in figure 1.

Table 2.

Anxiety symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, general stress and nursing stress in nurses grouped by years of service (n=745)

| Career stage |

F | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early (n=331) | Middle (n=282) | Late (n=132) | ||

| ASI-3 subscales | ||||

| Physical | 3.69 (3.958) | 5.40 (5.066) | 5.15 (5.044) | 11.631*** |

| Cognitive | 3.78 (3.563) | 5.66 (5.299) | 5.40 (5.126) | 14.307*** |

| Social | 5.30 (3.896) | 6.19 (5.095) | 6.05 (4.927) | 3.222* |

| Overall ASI-3 | 12.76 (10.408) | 17.25 (14.595) | 16.60 (14.498) | 10.225*** |

| BAI | 7.21 (6.962) | 9.07 (8.389) | 8.44 (8.186) | 4.481* |

| PSS-10 | 16.46 (4.372) | 18.05 (4.582) | 16.55 (5.007) | 10.168*** |

| NSS | 59.43 (10.624) | 60.18 (10.978) | 63.77 (11.335) | 7.548** |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

ASI-3, Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; NSS, Nursing Stress Scale; PSS-10, 10-item Perceived Stress Scale.

Figure 1.

Physical, cognitive and social anxiety sensitivity scores in nurses grouped by years of service. ASI-3, Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3.

For overall AS scores, homogeneity of variances was not assumed (p<0.001). Post hoc Dunnett T3 contrasts indicated that early career nurses scored significantly lower on ASI-3 than middle career nurses (p<0.001) and late career nurses (p<0.05). In contrast, no significant difference was found in overall AS scores between the middle and late career nurses.

For all subscales of ASI-3, homogeneity of variances was not assumed (all p<0.001). Post hoc Dunnett T3 tests showed that middle career nurses scored significantly higher than early career nurses on physical(p<0.001), social (p<0.05) and cognitive(p<0.001) subscales. Meanwhile, late career nurses scored significant higher than early career nurses on cognitive (p<0.01) and physical (p<0.05) subscales. There was no significant difference in AS subscales between middle and late career nurses.

Relationship between AS and nursing stress

Regression of cognitive subscale of ASI-3 on nursing stress subscales

In model 1, controlling variables had a significant effect on the cognitive subscale (F=44.912, p<0.001), accounting for 19.6% of variance. Significant association was found between cognitive subscale and years of service (β=0.135, p<0.01) and general stress (β=0.423, p<0.001). Model 2 was significant when nursing stress subscales were entered. R2 change was 0.096, implying that nursing stress accounted for 9.6% of the variance of cognitive AS after controlling for general stress and years of service. Nursing stress caused by conflict with physicians (β=0.172, p<0.001), lack of support (β=0.090, p<0.05) and heavy workload (β=0.176, p<0.001) were positively associated with cognitive AS (table 3).

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression analysis on anxiety sensitivity subscale score (n=745)

| ASI-3_cognitive |

ASI-3_ physical |

ASI-3_soical |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Standardised coefficients | Standardised coefficients | Standardised coefficients | Standardised coefficients | Standardised coefficients | Standardised coefficients | |

| Controlling variables | ||||||

| Years of service | 0.135** | 0.072 | 0.157** | 0.099* | 0.067 | 0.006 |

| Marital status | −0.068 | −0.057 | −0.070 | −0.058 | −0.067 | −0.053 |

| Having children | 0.055 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.005 | 0.013 | −0.005 |

| General stress | 0.423*** | 0.311*** | 0.381*** | 0.278*** | 0.350*** | 0.236*** |

| Nursing stress subscales | ||||||

| Death and dying | 0.030 | 0.029 | 0.022 | |||

| Conflict with physicians | 0.172*** | 0.160** | 0.155** | |||

| Inadequate preparation | −0.043 | −0.056 | 0.003 | |||

| Lack of support | 0.090* | 0.078 | 0.063 | |||

| Conflict with other nurses | 0.015 | 0.058 | 0.019 | |||

| Workload | 0.176*** | 0.180*** | 0.171*** | |||

| Uncertainty concerning treatment | −0.020 | −0.056 | 0.007 | |||

| F (p) | 44.912 (0.000) | 27.200 (0.000) | 35.844 (0.000) | 21.902 (0.000) | 25.532 (0.000) | 18.536 (0.000) |

| R2 | 0.201 | 0.297 | 0.167 | 0.254 | 0.125 | 0.223 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.196 | 0.286 | 0.162 | 0.242 | 0.120 | 0.211 |

| Changed R2 | 0.201 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.087 | 0.125 | 0.099 |

ASI-3, Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Regression of physical subscale of ASI-3 on nursing stress subscales

In model 1, controlling variables had a significant effect on the physical subscale (F=35.844, p<0.001), accounting for 16.2% of variance, and we found a significant association between physical subscale and years of service (β=0.157, p<0.01) and general stress (β=0.381, p<0.001). Model 2 was significant when nursing stress subscales were entered. R2 change was 0.087, implying that nursing stress could account for 8.7% of the variance of physical AS after controlling for general stress and years of service. Nursing stress related to conflict with physicians (β=0.160, p<0.01) and work load (β=0.180, p<0.001) were positively associated with the physical subscale (table 3).

Regression of social subscale of ASI-3 on nursing stress subscales

In model 1, controlling variables had a significant effect on the social subscale (F=25.532, p<0.001), accounting for 12.0% of variance. General stress (β=0.350, p<0.001) was positively associated with social AS, whereas years of service, marital status and having children had no significant effect on social AS. Model 2 was significant when nursing stress was entered. R2 change was 0.099, implying that nursing stress could account for 9.9% of the variance of social AS after controlling for general stress. Nursing stress related to conflict with physicians (β=0.155, p<0.01) and workload (β=0.171, p<0.001) were positively associated with social AS (table 3).

Discussion

The stressful working environment of female nurses in China appears to have had an adverse influence on their mental health. This study investigated AS, a risk factor for anxiety that might be changed by stress, among female Chinese nurses.

In this study, 32.8% of nurses had anxiety symptoms. Though this rate was lower than that of Chinese nurses in Gong et al,26 it was higher than those of the Chinese general population and nurses of USA, Singapore and Japan. This indicates that female Chinese nurses are more vulnerable to develop anxiety symptoms and require appropriate psychological intervention. Moreover, in accordance with Wang et al's17 finding in Chinese women, AS was significantly positively correlated with anxiety symptoms in female Chinese nurses. This further confirms AS's potential role in the development of anxiety symptoms.

Consistent with our hypothesis, there were significant differences in AS across groups. Experienced female Chinese nurses scored higher on AS than did early career nurses, whereas no significant difference in AS was found between middle and late career nurses. This indicates that for female Chinese nurses, the middle career stage might be a critical period for the development of AS, and late career stage might be the period in which AS gradually becomes stabilised. As a result, psychological intervention targeting AS may be most effective when provided for middle career nurses.

In hierarchical regression analysis, we examined the relationship between nursing stress and AS after controlling for years of service, marital status, having children and general stress. We found that nursing stress was significantly associated with all aspects of AS. The possible mechanism behind this might be that adaptation to stressful events at work elicits anxiety-related sensations and cognitions. Individuals who become more aware of these sensations and cognitions as well as their causes and consequences may develop negative beliefs about them and this could lead to increased AS.12

Workload-related stress and conflict with physicians were associated with all aspects of AS, while lack of support at work was associated with cognitive AS. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association between nursing stress and unique facets of AS; thus, little is known about the mechanism behind it. However, existing research and theories on occupational stress and anxiety seem to support the present findings. According to the JDC model by Karasek,27 individuals tend to have anxiety symptoms when the job demand is high, and the job control (decision latitude) and social interactions (social support) are low. In China, nursing professions are associated with high workload, irregular working hours and high job demand.26 Most Chinese public hospitals face serious nursing shortages. In the midst of healthcare reform, Chinese nurses are required to provide high-quality care to patients who expect excellent service. As a result, Chinese nurses may become more likely to develop AS which may then lead to anxiety symptoms. In a prospective study of Melchior et al,28 individuals with more workload-related stressors were twice as likely to have anxiety symptoms compared to those with low job demands. A similar finding was found by Fiabane et al,29 who reported that a greater risk of developing anxiety among healthcare workers was caused by a heavy workload.

In addition, Chinese nurses were considered to be subordinate to clinicians who occupied the dominant position in the healthcare system.1 30 Nurses were frequently criticised by clinicians and should follow clinicians' order regarding patients' treatment.31 This may result in conflict with physicians and feeling a lack of job control, hence predisposing nurses to the development of AS. Moreover, Chinese nurses lacked the time and opportunity to share feelings with colleagues at work,32 which might render them more vulnerable to develop fears of cognitive-related anxiety sensation. As Belsher et al33 suggested, individuals with greater social constraints were more likely to have negative cognition.

This study indicated that the working environment of Chinese nurses, especially the physician–nurse relationship and great workload, needs to be improved. Though recent studies suggested that the physician–nurse relationship among Chinese nurses had become relatively more favourable,34 35 the current finding indicated that the situation might not be optimal and the physician–nurse relationship should not be ignored. Specifically, the current findings suggested that the physician–nurse conflict may be prevalent in general hospital units and have a long-term negative influence on the mental and physical health of Chinese nurses. In addition, the unfavourable physician–nurse relationship and the great workload might influence the quality of health service provided to patients and thus cause a deterioration in the physician–nurse–patient relationship, further worsening the working environment.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, owing to the cross-sectional nature of this study, the causal inference between nursing stress and increase in AS level cannot be made. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to confirm and expand the conclusions from our study. Moreover, this study was conducted in a public hospital in central south China. Future studies need to verify the conclusions of this study among nurses in other types of health facilities in China. Last but not the least, the research did not explore the influence of stress from patient–nurse conflict on AS. Future research could examine whether patient–nurse conflict affects AS among Chinese nurses.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated that after years of exposure to stressful events during nursing, experienced female Chinese nurses were more sensitive to anxiety than early career nurses, suggesting the middle career stage might be a critical period for psychological intervention of AS. One potential suggestion based on past and present research is that hospital administrators should reduce nurses' workload and improve their professional status. Meanwhile, more social support and appropriate psychological intervention would be beneficial to nurses with higher AS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China who supported this research. The authors are also very grateful to the Department of Nursing Care of Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, which took part in the research and the participants for devoting their time to complete the questionnaires.

Footnotes

Contributors: SL, LL and XZ conceived and designed the study. SL, LL and YW organised and supervised data collection and input. SL drafted the paper, as well as organised and supervised the data analysis. JZ, YY and YW provided critical comments on various drafts of the paper. JZ, LZ and LL helped to organise data collection, and commented on drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key Technologies R&D programme in the 11th 5-year-plan from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (grant number: 2009BAI77B06).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The ethics committee of Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Gao YQ, Pan BC, Sun W et al. . Anxiety symptoms among Chinese nurses and the associated factors: a cross sectional study. BMC psychiatry 2012;12:141–9. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao R, Fang XY. Nurses’ stress and coping style: characteristics and its relationship with mental health. Chin Ment Health J 2005;19:607–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gramstad TO, Gjestad R, Haver B. Personality traits predict job stress, depression and anxiety among junior physicians. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:150–8. 10.1186/1472-6920-13-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiss S, McNally RJ. The expectancy model of fear. In: Reiss S, Bootzin RR, eds. Theoretical Issues in Behavior Therapy. New York: Academic Press, 1985:107–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ et al. . Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychol Assess 2007;19:176–88. 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM et al. . Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 1986;24:1–8. 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor S. Anxiety sensitivity: theory, research, and treatment of the fear of anxiety. Irving B, ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt NB, Lerew DR, Joiner TE. Prospective evaluation of the etiology of anxiety sensitivity: test of a scar model. Behav Res Ther 2000;38:1083–95. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00138-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein MB, Schork NJ, Gelernter J. Gene-by-environment (serotonin transporter and childhood maltreatment) interaction for anxiety sensitivity, an intermediate phenotype for anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008;33:312–19. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zavos HM, Wong CC, Barclay NL et al. . Anxiety sensitivity in adolescence and young adulthood: the role of stressful life events, 5HTTLPR and their interaction. Depress Anxiety 2012;29:400–8. 10.1002/da.21921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein MB, Jang KL, Livesley WJ. Heritability of anxiety sensitivity: a twin study. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:246–51. 10.1176/ajp.156.2.246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Stressful life events, anxiety sensitivity, and internalizing symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 2009;118:659–69. 10.1037/a0016499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watt MC, Stewart SH, Lefaivre MJ et al. . A brief cognitive-behavioral approach to reducing anxiety sensitivity decreases pain-related anxiety. Cognitive behavior therapy 2006;35:248–56. 10.1080/16506070600898553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smits JA, Berry AC, Tart CD et al. . The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral interventions for reducing anxiety sensitivity: a meta-analytic review. Behav Res Ther 2008;46:1047–54. 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tull MT, Schulzinger D, Schmidt NB et al. . Development and initial examination of a brief intervention for heightened anxiety sensitivity among heroin users. Behav Modif 2007;31:220–42. 10.1177/0145445506297020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lou JH, Yu HY, Hsu HY et al. . A study of role stress, organizational commitment and intention to quit among male nurses in southern Taiwan. J Nurs Res 2007;15:43–53. 10.1097/01.JNR.0000387598.40156.d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Liu WT, Zhu XZ et al. . Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the anxiety sensitivity index-3 in health adult women. Chin Ment Health J 2014;28:767–71. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G et al. . An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56:893–7. 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shulman LM, Taback RL, Rabinstein AA et al. . Non-recognition of depression and other non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2002;8:193–7. 10.1016/S1353-8020(01)00015-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng JR, Huang ZR, Huang JJ et al. . A study of psychometric properties, normative scores and factor structure of Beck Anxiety Inventory Chinese Version. Chin J Clin Psychol 2002;10:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong B, Yao SQ. Depressive symptoms and related influential factors in left-behind women in rural area. Chin J Clin Psychol 2012;20:839–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray-Toft P, Anderson JG. The nursing stress scale: development of an instrument. J Behav Assess 1981;3:11–23. 10.1007/BF01321348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M, Holzemer W, Faucett J. Psychometric evaluation of the Nursing Stress Scale (NSS) among Chinese nurses in Taiwan. J Nurs Meas 2007;15:133–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles J, Shevlin M. Applying regression and correlation. London: Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong Y, Han T, Chen W et al. . Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and related risk factors among physicians in China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e103242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 1979;24:285–307. 10.2307/2392498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melchior M, Caspi A, Milne BJ et al. . Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychol Med 2007;37:1119–29. 10.1017/S0033291707000414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiabane E, Giorgi I, Sguazzin C et al. . Work engagement and occupational stress in nurses and other healthcare workers: the role of organisational and personal factors. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:2614–24. 10.1111/jocn.12084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Z, Wu Y, Zhao X et al. . Investigation of patients’ cognition for social status of physicians and nurses. Chin J Prac Nurs 2008;24:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng J, Dai H. Probe into solving doctor-nurse conflicts in operation room and constructing a harmony doctor-nurse relationship. Chin Nurs Res 2006;28:42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma G, Zhao X, Qiu S. Correlation analysis between social support and anxiety state of nurses. J Nurs Sci 2006;21:48–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belsher BE, Ruzek JI, Bongar B et al. . Social constraints, posttraumatic cognitions, and posttraumatic stress disorder in treatment-seeking trauma survivors: evidence for a social-cognitive processing model. Psychol Trauma 2012;4:386–91. 10.1037/a0024362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y-E, While A, Li S-J et al. . Job satisfaction and work related variables in Chinese cardiac critical care nurses. J Nurs Manage 2015;23:487–97. 10.1111/jonm.12161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu K, You LM, Chen SX et al. . The relationship between hospital work environment and nurse outcomes in Guangdong, China: a nurse questionnaire survey. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:1476–85. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03991.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]