Abstract

Objective

To assess the clinical and haemodynamic effects of carvedilol for patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

Design

A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

We searched PubMed, Cochrane library databases, EMBASE and the Science Citation Index Expanded through December 2015. Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included.

Outcome measure

We calculated clinical outcomes (all-cause mortality, bleeding-related mortality, upper gastrointestinal bleeding) as well as haemodynamic outcomes (hepatic venous pressure (HVPG) reduction, haemodynamic response rate, post-treatment arterial blood pressure (mean arterial pressure; MAP) and adverse events).

Results

12 RCTs were included. In 7 trials that looked at haemodynamic outcomes compared carvedilol versus propranolol, showing that carvedilol was associated with a greater reduction (%) of HVPG within 6 months (mean difference −8.49, 95% CI −12.36 to −4.63) without a greater reduction in MAP than propranolol. In 3 trials investigating differences in clinical outcomes between carvedilol versus endoscopic variceal band ligation (EVL), no significant differences in mortality or variceal bleeding were demonstrated. 1 trial compared clinical outcomes between carvedilol versus nadolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate (ISMN), and showed that no significant difference in mortality or bleeding had been found. 1 trial comparing carvedilol versus nebivolol showed a greater reduction in HVPG after 14 days follow-up in the carvedilol group.

Conclusions

Carvedilol may be more effective in decreasing HVPG than propranolol or nebivolol and it may be as effective as EVL or nadolol plus ISMN in preventing variceal bleeding. However, the overall quality of evidence is low. Further large-scale randomised studies are required before we can make firm conclusions.

Trial registration number

CRD42015020542.

Keywords: CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the most comprehensive review on this subject, and we followed the Cochrane style strictly in preparing this manuscript.

One of the limitations is the lack of randomised controlled trials when comparing carvedilol versus endoscopic variceal band ligation.

Introduction

Acute variceal bleeding is the most feared and devastating complication of cirrhosis. Six-week mortality is ∼10–20%, ranging from 0% for patients with Child-Pugh class A to ∼30% for patients with Child-Pugh class C.1–3 The 1-year rate of recurrent variceal bleeding is ∼60%.4 Although some risk factors are known, such as red wale marks on the varices, large variceal size and advanced pre-existing liver disease,5 the measurement of portal pressure with hepatic venous pressure (HVPG) is the best method for estimating the risk of bleeding varices. HVPG>10 mm Hg is the strongest predictor of the development of varices; HVPG>12 mm Hg is associated with a high risk of variceal bleeding. For patients with acute variceal bleeding, HVPG>20 mm Hg has been associated with high mortality.6 7 Bleeding is less likely if HVPG decreases to <12 mm Hg or decreases by 20% from the baseline figure.8 9

Various types of drugs have been used to decrease HVPG. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines recommended using non-selective β-blockers (NSBBs), such as propranolol or nadolol, with or without isosorbide-5-mononitrate (ISMN) to prevent variceal bleeding.3 Reduction of HVPG is achieved by decreasing the cardiac output (β1-blockade) and constricting the splanchnic vessels (β2-blockade). Only ∼40% of treated patients reach therapeutic levels, and the risk of variceal bleeding remains high for haemodynamic non-responders.10 11 Carvedilol, which blocks both α and β receptors, was reported to have better results than NSBBs by additionally decreasing intrahepatic resistance. For propranolol non-responders, carvedilol may still achieve a haemodynamic response rate as high as 56%.11 However, carvedilol was reported to be associated with some severe adverse effects, such as systemic hypotension and renal failure, especially in patients with refractory ascites.12 13 Whether carvedilol is better than NSBBs requires further research. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the benefits and adverse effects of carvedilol in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

Methods

The protocol has been registered on the PROSPERO registry under registration number CRD42015020542.

Types of studies

We included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing carvedilol versus propranolol or other interventions for participants with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, irrespective of the publication status, language or blinding. Abstracts were included.

Types of participants

The participants were patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, regardless of the aetiology of cirrhosis or the severity of cirrhosis, who were >18 years old.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing carvedilol versus propranolol or any other intervention. Any co-interventions were allowed if they were used in both arms of the trial.

Treatment outcomes

The primary outcomes were: (1) all-cause mortality, (2) bleeding-related mortality and (3) upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The secondary outcomes were: (1) HVPG reduction, assessed as a percentage; (2) haemodynamic response rate; (3) post-treatment MAP and (4) adverse events.

For all-cause mortality, upper gastrointestinal bleeding and bleeding-related mortality, trials with follow-ups longer than 7 days were included. Percentage of HVPG reduction, haemodynamic response rate and post-treatment MAP were assessed separately within 24 h (acute term), at 24 h to 6 months (short term) and at >6 months (long term). The haemodynamic response rate was defined as a rate of HVPG reduction ≥20% of the baseline value or ≤12 mm Hg.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE and Science Citation Index Expanded databases for published articles. The search strategies with the expected time spans are displayed in onlinesupplementary appendix1.

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix1.pdf (60KB, pdf)

We also searched clinical trials databases (ClinicalTrials.gov; WHO International Clinical Trial Registry Platform; International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (ISRTN) registry) for planned and ongoing trials. We searched the Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI-S/CPCI-SSH), BIOSIS previews and Derwent Innovation Index (DII) databases for conference proceedings and innovations. We reviewed the reference lists of the retrieved articles for potentially relevant studies; we attempted to contact the corresponding authors of relevant studies to request information on unpublished articles. We also sent letters to the authors of abstracts and articles with incomplete data to obtain additional information.

Data collection and analysis

Three authors (TL, XC and JL) selected studies for inclusion following the PRISMA process. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with other authors (PS and AB). The reasons for exclusion were recorded. Two authors (WK and WX) extracted data from the included studies; disagreements were discussed with another author (YH).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.14 Two authors (WK and YH) conducted the assessment of the risk of bias. Disagreements were discussed with other authors (QZ and AB). We classified trials with a low risk of bias if none of the domains were associated with an unclear or high risk of bias; otherwise, an unclear (at least one domain was assessed as having unclear risk without any high-risk domains) or high risk of bias was classified.

Statistical methods

We used relative ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs to calculate dichotomous data and the mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs to calculate continuous data. We used HRs with 95% CIs as relevant effect measures for mortality and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. We estimated HRs from the log-rank χ2 statistic, log-rank p values, given numbers of events or Kaplan-Meier curves, using methods presented by Tierney et al.15 In one three-arm study, only two arms were used.16

We performed statistical analysis following the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and using Review Manager software (RevMan, V.5.3, Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).14 A random-effects model was chosen a priori for all of the analyses, and then the fixed-effects model was performed as a sensitivity test. If the two models yielded the same results, no significant heterogeneity was considered; if the 95% CI for the average intervention effect was wider in the random-effects model, the heterogeneity between studies was considered. We also calculated the χ2 and I2 statistics. The p<0.10 or I2>50% was considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity. If significant heterogeneity was found, potential reasons for heterogeneity were explored.

For missing data, analyses were performed using the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle (best-case/worst-case scenario for dichotomous outcomes: mortality, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, haemodynamic response rate), as well as per protocol principle (for all of the outcomes).

Subgroup analysis

We performed subgroup analysis to identify the impact of type of controlled group (trials using ISMN in addition to NSBBs, compared with trials using NSBBs alone).

Sensitivity analysis

We excluded the trials published as abstracts and trials that used ISMN in addition to NSBBs to perform sensitive analysis. We did not exclude trials with a high risk of bias because only a few studies with a low risk of bias were included in the meta-analysis.

Summary of findings tables

We used ‘summary of findings’ tables to present our assessment of the body of evidence associated with some outcomes, using GRADEPro software (ims.cochrane.org/revman/other-resources/gradepro). The quality of a body of evidence considers five factors regarding the limitations of the studies: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias.

Results

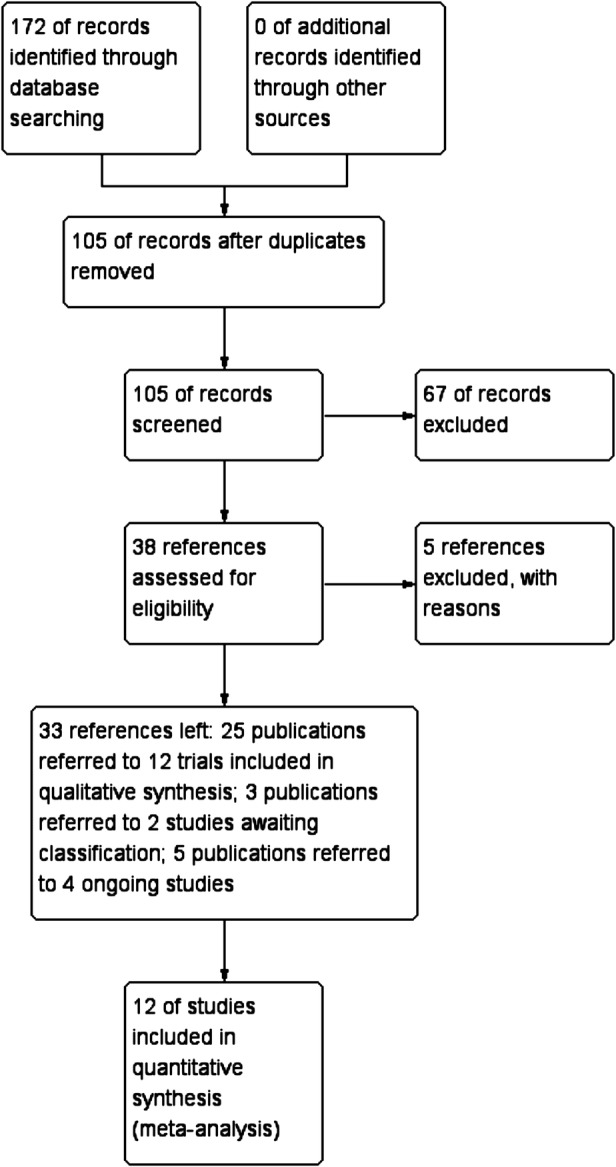

Results of the search

From 172 identified publications, 67 duplicates were removed. From the remaining 105 publications, 67 were removed due to non-randomised designs or irrelevance regarding our topic. We assessed the full-text versions of the remaining 38 publications. Five publications were excluded: two were published as Master's theses referring to one trial, which reported largely different results, and the methods of randomisation were questionable;17 18 one was a non-randomised trial;19 one was irrelevant to our topic;20 and one included non-cirrhotic participants.21 Finally, of the remaining 33 publications, 25 referring to 12 trials were included in the quantitative synthesis;10 16 22–31 3 referring to 2 trials were awaiting classification,32 33 and 5 referring to 4 trials were ongoing projects (figure 1).34–37

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Description of the individual comparisons in the trials

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in table 1 and online supplementary appendices 2 and 3. The summary of findings table is shown in online supplementary appendix 4.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author year | Group | N of Pati Carv/Cont |

Administration of intervention | Time of outcome assessment | Drop Carv/Cont | ITT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banares 199916 | Carv/Prop | 14/14 | Carv: 25 mg four times a day orally Prop: 0.15 mg/kg intravenously followed by a continuous infusion of 0.2 mg/kg |

60 min | 0/0 | No |

| Banares 200227 | Carv/Prop | 26/25 | Carv: 31±4 mg orally Prop: 73±10 mg orally |

11.1±4.1 weeks | 2/3 | No |

| De 200223 | Carv/Prop | 18/18 | Carv: start at 25 mg four times a day orally followed by 6.25 mg twice daily Prop: start at 80 mg four times a day orally followed by 40 mg twice daily |

90 min; 7 days |

I/2 | No |

| Hobolth 201210 | Carv/Prop | 24/23 | Carv: start at 3.125 mg twice daily, followed by 14±7 mg/day orally Prop: start at 40 mg twice daily, orally followed by 122±64 mg/day |

90 min; 92.7±13.6 days |

3/6 | No |

| Lin 200422 | Carv/Prop+ISMN | 11/11 | Carv: 25 mg, four times a day, orally Prop: 40 mg plus ISMN (20 mg), four times a day, orally |

90 min | 0/0 | No |

| Lo 201229 | Carv/Nado+ ISMN | 61/60 | Carv: 10.4±2.2 mg/day orally Nado: 45±13 mg+20 mg ISMNs/day orally |

30 months | 5/6 | Yes |

| Mo 201431 | Carv/Prop | 48/48 | Carv: started at 12.5 mg, four times a day orally then adjusted according to the BP, HR Prop: started at 10 mg, three times a day, orally then adjusted according to the BP, HR |

7 days | 0/0 | No |

| Shah 201425 | Carv/EVL | 82/86 | Carv: 6.25 mg four times a day for 1 week, 6.25 mg twice daily thereafter orally EVL: underwent EVL within 48 h of randomisation, repeated every 3 weeks |

13 months | 2/0 | Yes |

| Silkauskaite 201324 | Carv/Nebi | 10/10 | Carv: 25 mg four times a day orally Nebi: 5 mg four times aday orally |

60 min; 14 days |

1/2 | No |

| Sohn 201330 | Carv/Prop | 50/49 | Carv: 11.6±2.2 mg/day orally Prop: 153.5±100.2 mg/day orally |

6 weeks | 8/11 | Yes |

| Stanley 201426 | Carv/EVL | 33/31 | Carv: 6.25 mg four times a day for the first week, 12.5 mg/day thereafter orally EVL: underwent EVL within 1 week, then repeated every 2 weeks |

26.4 months | 14/11 | Yes |

| Tripathi 200928 | Carv/EVL | 77/75 | Carv: started at 6.25 mg four times a day for the first week; 12.5 mg thereafter orally EVL: underwent EVL every 2 weeks |

26 months | 25/23 | Yes |

BP, blood pressure; Carv, carvedilol; Cont, control; EVL, endoscopic variceal band ligation; ISMN, isosorbide-5-mononitrate; ITT, intention-to-treat analysis; Nado, nadolol; Nebi, nebivolol; Pati, patients; Prop, propranolol.

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix2.pdf (250.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix3.pdf (137.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix4.pdf (360.4KB, pdf)

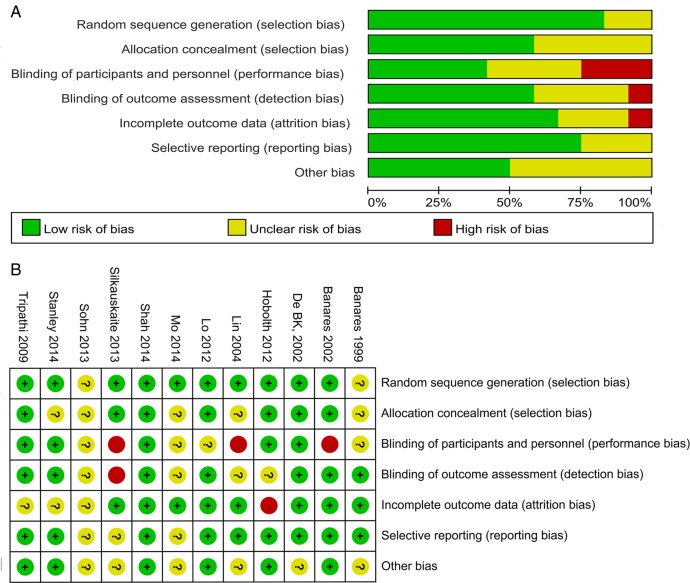

Twelve trials were associated with a low (one), unclear (seven) or high (four) risk of bias. The details can be seen in the ‘risk of bias graph’ (figure 2A) and ‘risk of bias summary’ (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias. Risk of bias graph (A); risk of bias summary (B).

Carvedilol versus propranolol

Description of included studies

Seven trials (one abstract) with 379 participants compared carvedilol versus propranolol;10 16 22 23 27 30 31 six trials were two-arm (carvedilol vs propranolol) studies, and one trial was a three-arm study (carvedilol vs propranolol vs placebo).16 One of the studies used ISMN in addition to propranolol in the controlled group.22 Haemodynamic outcomes had been reported in each trial, and treatment effects were assessed within 24 h (acute term)10 16 22 23 and within 6 months (24 h to 6 months; short term).10 23 27 30 31 No trials reported long-term outcomes.

Six trials reported the sex of the participants: 199 were male, and 79 were female.10 16 22 23 27 31 The mean age of the participants ranged from 42 to 61 years. Most trials mainly included participants with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis; the most common causes of cirrhosis were alcohol abuse (three trials),10 16 23 hepatitis B virus infection (one trial)22 and hepatitis C virus infection (one trial).27 Two trials did not report the aetiologies of cirrhosis.30 31

The characteristics of included studies and included participants as well as the administration of each drug could be seen in table 1 and online supplementary appendices 2 and 3.

Effects of interventions

One trial recruited 47 participants with a follow-up about 90 days reported mortality (RR 2.88, 95% CI 0.12 to 67.29), bleeding-related mortality (RR 2.88, 95% CI 0.12 to 67.29) and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.06 to 14.43), but no significant difference had been found for these outcomes.10 The risk of bias was high because of the incomplete outcome data.

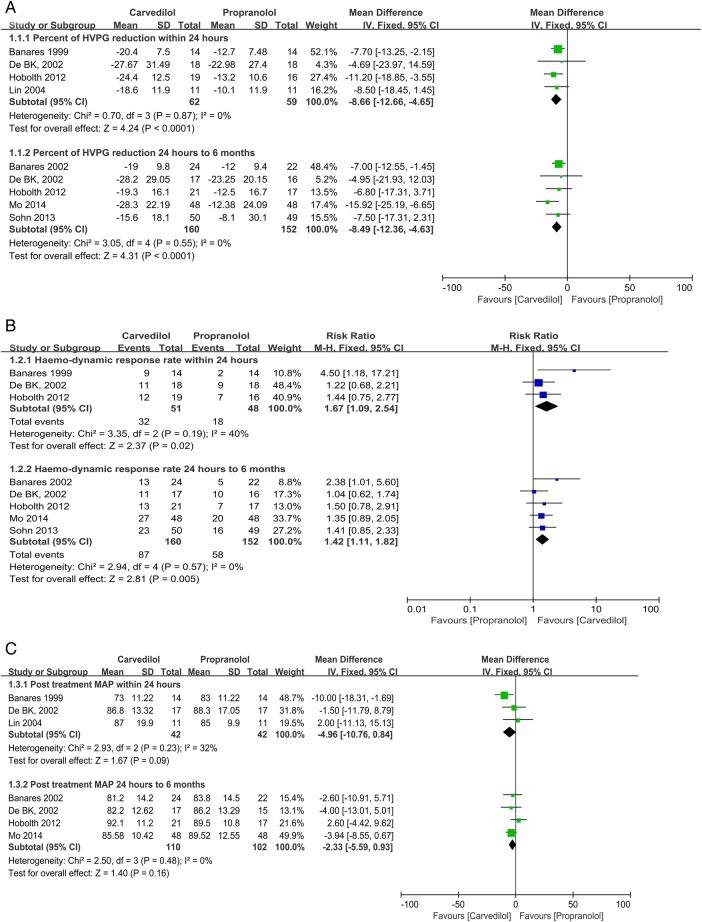

Percentage (%) of HVPG reduction

Percentage (%) of HVPG reduction within 24 h: Four trials with an unclear (2) or a high (2) risk of bias reported acute-term HVPG reductions after drug administration.10 16 22 23 No significant heterogeneity was found; the fixed-effects model showed that carvedilol was associated with a greater reduction (%) in HVPG (MD −8.66, 95% CI −12.66 to −4.65) (figure 3A). The result of a sensitive analysis that excluded the trial using propranolol plus ISMN as the control remained consistent with the pooled analysis (see online supplementary appendix 5).

Figure 3.

Carvedilol versus propranolol. Percentage of hepatic venous pressure (HVPG) reduction (1.1.1 outcome assessed within 24 h; 1.1.2 outcome assessed 24 h–6 months; A); haemodynamic response rate (1.2.1 outcome assessed within 24 h; 1.2.2 outcome assessed 24 h–6 months; B); post-treatment MAP (1.3.1 outcome assessed within 24 h; 1.3.2 outcome assessed 24 h–6 months; C).

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix5.pdf (672.6KB, pdf)

Percentage (%) of HVPG reduction at 24 h to 6 months: Five trials with an unclear (3) or a high (2) risk of bias reported the short-term percentage (%) of HVPG reduction after drug administration.10 23 27 30 31 Four were reported as full texts, while the other was presented as an abstract.30 No significant heterogeneity was found. The fixed-effects model showed that carvedilol was associated with a greater reduction (%) in HVPG (MD −8.49, 95% CI −12.36 to −4.63; figure 3A). The results of sensitivity analysis that excluded the trial reported as an abstract remained consistent with the pooled analysis (see online supplementary appendix 5).

Haemodynamic response rate

Haemodynamic response rate within 24 h: Three trials with an unclear (2) and a high (1) risk of bias reported the acute-term haemodynamic response rate after drug administration.10 16 23 It was 32 of 51 in the carvedilol group versus 18 of 48 in the propranolol group. The χ2 result was 3.35, I2 was 40%. The fixed-effects model found a higher haemodynamic response rate in the carvedilol group (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.54; figure 3B), while the random-effects model found no significant difference between the studies (RR 1.59, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.84). Best-case and worst-case scenario analyses were consistent with the per protocol analysis (see online supplementary appendix 5).

Haemodynamic response rate at 24 h to 6 months: Five trials with an unclear (3) or a high risk of bias (2) reported a short-term haemodynamic response rate.10 23 27 30 31 It was 87 of 160 in the carvedilol group versus 58 of 152 in the propranolol group. No significant heterogeneity was found. The fixed-effects model found that the carvedilol group had better results (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.82; figure 3B). The results of the ITT analysis, as well as the sensitivity analysis that excluded the trial reported as an abstract, remained consistent with the pooled analysis (see online supplementary appendix 5).

Post-treatment MAP

Post-treatment MAP within 24 h: Three trials with an unclear (2) or a high (1) risk of bias reported acute-term post-treatment MAP.16 22 23 The χ2 result was 2.93, and I2 was 32%. Both the random-effects and fixed-effects models found no statistically significant difference between groups (fixed effects: MD −4.96, 95% CI −10.76 to 0.84; figure 3C). The results of the sensitive analysis, which excluded the trial using propranolol plus ISMN as a control, remained consistent with the pooled analysis (see online supplementary appendix 5).

Post-treatment MAP at 24 h to 6 months: Four trials with an unclear (2) or a high (2) risk of bias reported the short-term post-treatment MAP.10 23 27 31 No significant heterogeneity was found. The fixed-effects model found no statistically significant difference between groups (MD −2.33, 95% CI −5.59 to 0.93; figure 3C).

Adverse events

Three trials with an unclear (1) to a high (2) risk of bias reported adverse events.10 23 27 No significant heterogeneity was found. The fixed-effects model found no statistically significant difference between groups for any single adverse effect (see online supplementary appendix 6).

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix6.pdf (58.2KB, pdf)

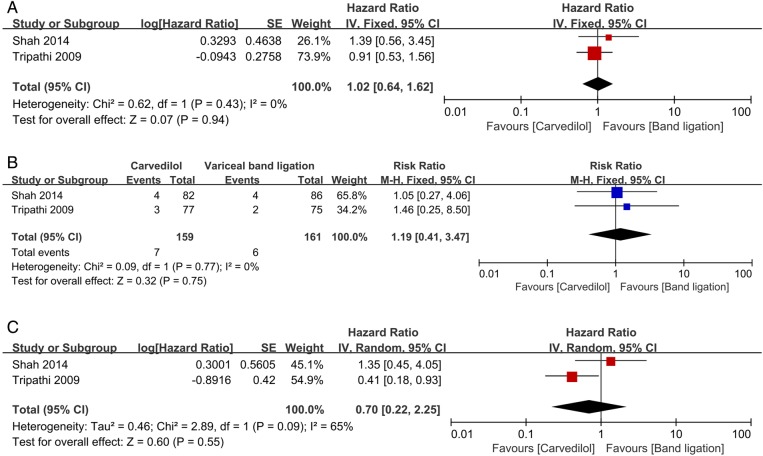

Carvedilol versus endoscopic variceal band ligation

One trial with an unclear risk of bias investigated the secondary prevention of bleeding. The trial included 64 participants with a median follow-up of 26 months. Most of them were with Child-Pugh class B cirrhosis; the most common cause of cirrhosis was alcohol abuse. No significant difference had been found between groups on mortality (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.30 to 2.35; RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.02), bleeding-related mortality (RR 4.70, 95% CI 0.58 to 37.99) and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.42 to 3.32; RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.55).26

Two trials with a low or unclear risk of bias examined the efficacy of primary prophylaxis,25 28 341 participants were included; the median length of follow-up was 26 months in one trial and 13 months in the other. The age of the participants ranged from 43 to 64 years. Trials mainly included participants with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis; the most common causes of cirrhosis were alcohol abuse and hepatitis C virus infection. No significant difference had been found between groups on mortality (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.62; RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.58; figure 4A), bleeding-related mortality (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.41 to 3.47; figure 4B) and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.25; RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.20; figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Carvedilol versus endoscopic variceal band ligation for primary prophylaxis. All-cause mortality (A); bleeding-related mortality (B); upper gastrointestinal bleeding (C).

For adverse events, carvedilol was reported to cause less chest pain and transient dysphagia but more shortness of breath and nausea (see online supplementary appendix 7).25 26 28

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix7.pdf (78.2KB, pdf)

Carvedilol versus other drugs

Carvedilol versus nadolol

One trial with 121 participants reported on carvedilol versus nadolol plus ISMN.29 The trial only focused on clinical outcomes (mortality, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, etc). Treatment effects were assessed with a follow-up of ∼30 months (table 1 and online supplementary appendices 2 and 3). There were no statistically significant differences in all-cause mortality (HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.55; RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.57), bleeding-related mortality (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.79) or upper gastrointestinal bleeding (HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.17; RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.31). However, the carvedilol group had fewer adverse events (5/61 vs 23/61, RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.53).

Carvedilol versus nebivolol

One trial with 20 participants reported carvedilol versus nebivolol.24 Only haemodymanic results had been reported. Treatment effects were assessed within 24 h and 14 days after drug administration (table 1 and online supplementary appendices 2 and 3). No significant differences were found in acute-term percentage (%) of HVPG reduction (MD −9.50, 95% CI −19.82 to 0.82) or haemodynamic response rate (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.88 to 4.54). However, the carvedilol group showed better results in the short term for percentage (%) of HVPG reduction (MD −10.9, 95% CI −20.05 to −1.75) and haemodynamic response rate (RR 4.00, 95% CI 1.11 to 14.35). In addition, the carvedilol group showed higher post-treatment MAP within 24 h (MD 10.00, 95% CI 3.48 to 16.52). Only total numbers of adverse events were reported, and there were no statistically significant differences between groups (RR 0.5, 95% CI 0.05 to 4.67).

Excluded studies

The characteristics of the excluded studies are shown in onlinesupplementary appendix 8.

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix8.pdf (53.4KB, pdf)

Studies awaiting classification

There were two studies awaiting classification.32 33 Both trials had been completed, but no full text had yet been published, and data from the abstracts could not be used directly. We received no reply after requesting data (online supplementary appendix 9).

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix9.pdf (61.4KB, pdf)

Ongoing studies

We identified four ongoing trials.34–37 We hope that the results of these trials will be included in the update of this review (online supplementary appendix 10).

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix10.pdf (67.8KB, pdf)

Discussion

Carvedilol is an emerging therapy for portal hypertension. On the basis of its mechanism of action by α and β receptors blockade, it might have a more significant effect in decreasing HVPG than NSBBs. Some meta-analyses comparing carvedilol versus propranolol have been published,38–40 but none compared carvedilol versus endoscopic variceal band ligation (EVL) or other drugs; none focused on patient-orientated outcomes, such as mortality and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and fewer RCTs were included. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the most comprehensive review of this subject.

Carvedilol versus propranolol

This review showed that carvedilol is more effective than propranolol in decreasing HVPG acutely and over short-term follow-up. In addition, the short-term haemodynamic response rates were greater in the carvedilol group. Although no long-term outcomes were reported, one might infer that carvedilol would be effective beyond 6 months because the number of haemodynamic responders in the acute setting was almost identical to the outcomes at 6 months. One trial reported mortality and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. This trial was designed to evaluate haemodynamic effects and it is difficult to compare carvedilol with propranolol on mortality with a follow-up within 90 days.10 Recently, a non-randomised study including 104 participants with a follow-up of 2 years had assessed the efficacy of carvedilol for propranolol non-responders.11 It was reported that a significant proportion of propranolol non-responders could achieve haemodynamic responses to carvedilol treatment. In addition, the variceal bleeding rate, hepatic decompensation rate and mortality rate were significantly decreased in the haemodynamic response group. This study indicated that carvedilol might be better than propranolol in decreasing the HVPG and improving the survival of patients with cirrhosis.

Systemic hypotension is the main cause of drug discontinuance among patients using carvedilol. Although some participants developed severe systemic hypotension and withdrew from the trials,23 27 our study showed no significant differences between groups in post-treatment MAP for over acute-term and short-term follow-ups. The haemodynamic effect of carvedilol is dose dependent; an increase in the carvedilol dose from 6.25–12.5 to 25–50 mg/day significantly decreased MAP and HR further without an additional effect on HVPG.25 41 Thus, it is advised that carvedilol be started at a low dose (6.25 mg/day); if tolerated, the dose could be increased stepwise up to 12.5 mg/day. It must be noticed that carvedilol or NSBBs can increase the mortality of patients with decompensated cirrhosis (cirrhosis with refractory ascites or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis).12 13 These drugs can aggravate the disordered systemic circulation and induce acute kidney injury or other life-threatening complications under these circumstances.42 43

Carvedilol versus EVL

EVL is recommended for the primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding. It was reported that band ligation was better than NSBBs in preventing variceal bleeding, but it could not improve overall survival.44

In this study, we found no significant differences in overall mortality, bleeding-related mortality or upper gastrointestinal bleeding between groups for the primary and secondary prophylaxis. Carvedilol seems to have the same efficacy in prevention of variceal bleeding as EVL. However, only three studies were analysed, and the quality of evidence is low. More studies are needed to make firm conclusions.

Complications from carvedilol are often mild and subside after dose reduction or drug discontinuation. In contrast, the complications of EVL often require hospitalisation and can be lethal. It may be appropriate to restrict EVL to carvedilol non-responders or to patients who have contraindications to carvedilol. Furthermore, EVL requires frequent follow-up endoscopies because recurrence of varices requiring retreatment occurs in more than 50% of cases during the first year,45 significantly increasing the burden of patients physically and economically.

Carvedilol versus other drugs

Only one trial compared carvedilol versus nadolol plus ISMN, and one compared carvedilol versus nebivolol. Thus, more studies are needed before robust conclusions can be reached.

Conclusions

This systematic review found that carvedilol is more effective in decreasing HVPG than propranolol and it may be as effective as EVL in preventing variceal bleeding. However, the small number of patients recruited made it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Larger, better-designed studies are required to establish the efficacy of carvedilol.

Footnotes

Contributors: QZ is the guarantor of the article. TL, WK and PS were involved in study design, data collection, first draft of the article; these three authors contributed equally to this work. XC was involved in data analysis and research idea. AB was involved in data analysis, results interpretation, draft article corrections. YH, WX and JL were involved in data collection and statistical analysis. QZ was involved in study design, statistical analysis, final article writing. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The full data set is available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Bañares R et al. . Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J Hepatol 2008;48:229–36. 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:823–32. 10.1056/NEJMra0901512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Franchis R. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2010;53:762–8. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch J, García-Pagán JC. Prevention of variceal rebleeding. Lancet 2003;361:952–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brocchi E, Caletti G, Brambilla G et al. , North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med 1988;319:983–9. 10.1056/NEJM198810133191505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J et al. . Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2254–61. 10.1056/NEJMoa044456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moitinho E, Escorsell A, Bandi JC et al. . Prognostic value of early measurements of portal pressure in acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 1999;117:626–31. 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70455-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Amico G, Garcia-Pagan JC, Luca A et al. . Hepatic vein pressure gradient reduction and prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a systematic review. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1611–24. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abraldes JG, Tarantino I, Turnes J et al. . Hemodynamic response to pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension and long-term prognosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology 2003;37:902–8. 10.1053/jhep.2003.50133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobolth L, Moller S, Gronbaek H et al. . Carvedilol or propranolol in portal hypertension? A randomized comparison. Scand J Gastroenterol 2012;47:467–74. 10.3109/00365521.2012.666673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiberger T, Ulbrich G, Ferlitsch A et al. . Carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non-response to propranolol. Gut 2013;62:1634–41. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sersté T, Melot C, Francoz C et al. . Deleterious effects of beta-blockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology 2010;52:1017–22. 10.1002/hep.23775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P et al. . Nonselective beta blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1680–90. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D et al. . Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007;8:16 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bañares R, Moitinho E, Piqueras B et al. . Carvedilol, a new nonselective beta-blocker with intrinsic anti- Alpha1-adrenergic activity, has a greater portal hypotensive effect than propranolol in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1999;30:79–83. 10.1002/hep.510300124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren R, Zhang C. The comparison of recent curative effect on the reduction of hepatic vein pressure gradient in patients with cirrhosis (Master's thesis). 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qu X, Zhang C. The preliminary research of the short-term reduction of hepatic vein pressure gradient to predict the long-term curative effect of beta-blockers (Master's thesis). 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruha R, Vitek L, Petrtyl J et al. . Effect of carvedilol on portal hypertension depends on the degree of endothelial activation and inflammatory changes. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;41:1454–63. 10.1080/00365520600780403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonefeld K, Hobolth L, Juul A et al. . The insulin like growth factor system in cirrhosis: relation to changes in body composition following adrenoreceptor blockade. Growth Horm IGF Res 2012;22:212–18. 10.1016/j.ghir.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samanta T, Purkait R, Sarkar M et al. . Effectiveness of beta blockers in primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in children with portal hypertension. Trop Gastroenterol 2011;32:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin HC, Yang YY, Hou MC et al. . Acute administration of carvedilol is more effective than propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate in the reduction of portal pressure in patients with viral cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1953–8. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De BK, Das D, Sen S et al. . Acute and 7-day portal pressure response to carvedilol and propranolol in cirrhotics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17:183–9. 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02674.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silkauskaite V, Kupcinskas J, Pranculis A et al. . Acute and 14-day hepatic venous pressure gradient response to carvedilol and nebivolol in patients with liver cirrhosis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2013;49:467–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah HA, Azam Z, Rauf J et al. . Carvedilol vs. esophageal variceal band ligation in the primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol 2014;60:757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanley AJ, Dickson S, Hayes PC et al. . Multicentre randomised controlled study comparing carvedilol with variceal band ligation in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. J Hepatol 2014;61:1014–19. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bañares R, Moitinho E, Matilla A et al. . Randomized comparison of long-term carvedilol and propranolol administration in the treatment of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2002;36:1367–73. 10.1053/jhep.2002.36947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tripathi D, Ferguson JW, Kochar N et al. . Randomized controlled trial of carvedilol versus variceal band ligation for the prevention of the first variceal bleed. Hepatology 2009;50:825–33. 10.1002/hep.23045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo GH, Chen WC, Wang HM et al. . Randomized, controlled trial of carvedilol versus nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate for the prevention of variceal rebleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:1681–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sohn JH, Kim TY, Um SH et al. . A randomized, multi-center, phase IV open-label study to evaluate and compare the effect of carvedilol versus propranolol on reduction in portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis: an interim analysis. Hepatology 2013;58:990a 10.1002/hep.26874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mo CY, Li SL. Short-term effect of carvedilol vs propranolol in reduction of hepatic venous pressure gradient in patients with cirrhotic portal hypertension. [Chinese]. World Chin J Digestology 2014;22:4146–50. 10.11569/wcjd.v22.i27.4146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhardwaj A, Kedarisetty CK, Kumar M et al. . A prospective, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial of carvedilol for early primary prophylaxis of esophageal varices in cirrhosis. Hepatology. Conference: 65th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases: The Liver Meeting 2014, Boston, MA USA: 2014;60:278A.24700457 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fierbinteanu-Braticevici C, Udeanu M, Dragomir P et al. . The effects of carvedilol a nonselective beta-blocker on portal hemodynamics in cirrhosis. Rom J Intern Med 2003;41:247–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhardwaj A, Kumar A, Rangegowda D et al. . A prospective, open labeled, randomized controlled trial comparing carvedilol+VSL#3 versus evl for primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients non-responder to carvedilol (NCT01196481). Hepatology 2014;60:278A.24700457 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demyen M.2014. Carvedilol vs Band Ligation vs Combination Therapy for Primary Prophylaxis of Variceal Bleeding NCT02066649. https://clinicaltrials.gov/

- 36.Varea S.2010. Study on b-blockers to prevent decompensation of cirrhosis with HTPortal (PREDESCI) NCT01059396. https://clinicaltrials.gov/

- 37.Chen S.2015. The effect of carvedilol vs propranolol in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding NCT02385422. https://clinicaltrials.gov/

- 38.Sinagra E, Perricone G, D'Amico M et al. . Systematic review with meta-analysis: the haemodynamic effects of carvedilol compared with propranolol for portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:557–68. 10.1111/apt.12634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S, Wang JJ, Wang QQ et al. . The effect of carvedilol and propranolol on portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:961–70. 10.2147/PPA.S84762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguilar-Olivos N, Motola-Kuba M, Candia R et al. . Hemodynamic effect of carvedilol vs. propranolol in cirrhotic patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol 2014;13:420–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tripathi D, Therapondos G, Lui HF et al. . Haemodynamic effects of acute and chronic administration of low-dose carvedilol, a vasodilating beta-blocker, in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:373–80. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krag A, Wiest R, Albillos A et al. . The window hypothesis: haemodynamic and non-haemodynamic effects of beta-blockers improve survival of patients with cirrhosis during a window in the disease. Gut 2012;61:967–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ge PS, Runyon BA. When should the beta-blocker window in cirrhosis close? Gastroenterology 2014;146:1597–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung J, Zeman M, van Zanten SV et al. . Systematic review: secondary prevention with band ligation, pharmacotherapy or combination therapy after bleeding from oesophageal varices. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:577–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bosch J. Carvedilol for portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2010;51:2214–18. 10.1002/hep.23689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix1.pdf (60KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix2.pdf (250.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix3.pdf (137.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix4.pdf (360.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix5.pdf (672.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix6.pdf (58.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix7.pdf (78.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix8.pdf (53.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix9.pdf (61.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010902supp_appendix10.pdf (67.8KB, pdf)