Abstract

Objectives

To examine perceived communication barriers between urban consultants and rural family physicians practising routine and emergency care in remote subarctic Newfoundland and Labrador (NL).

Design

This study used a mixed-methods design. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected through exploratory surveys, comprised of closed and open-ended questions. The quantitative data was analysed using comparative statistical analyses, and a thematic analysis was applied to the qualitative data.

Participants

52 self-identified rural family physicians and 23 urban consultants were recruited via email. Rural participants were also recruited at the Family Medicine Rural Preceptor meetings in St John's, NL.

Setting

Rural family physicians and urban consultants in NL completed a survey assessing perceived barriers to effective communication.

Results

Data confirmed that both groups perceived communication difficulties with one another; with 23.1% rural and 27.8% urban, rating the difficulties as frequent (p=0.935); 71.2% rural and 72.2% urban as sometimes (p=0.825); 5.8% rural and 0% urban acknowledged never perceiving difficulties (p=0.714). Overall, 87.1% of participants indicated that perceived communication difficulties impacted patient care. Primary trends that emerged as perceived barriers for rural physicians were time constraints and misunderstanding of site limitations. Urban consultants' perceived barriers were inadequate patient information and lack of native language skills.

Conclusions

Barriers to effective communication are perceived between rural family physicians and urban consultants in NL.

Keywords: communication, rural, urban, EMERGENCY MEDICINE, barriers

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first scholarly examination of perceived communication barriers between urban specialists and rural family physicians in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL).

The themes that underpin these novel perceptions are discussed.

This study illuminates the need to further investigate communications between urban and rural physicians in NL.

The novel survey tool was not tested for reliability and validity.

This small survey study was based in one province.

Introduction

Communication is an integral part of the Physician Competency Framework, forming one of its seven supporting pillars.1 Safe reliable communication for routine and emergency medical care is important in rural and remote parts of the world like Newfoundland and Labrador (NL). It is critically important in NL's offshore, where fishing and industrial operations take place in unpredictable weather at subpolar latitudes, and medical support and rescue may require telecommunication with distant air and sea personnel. For example, when in February 1982, the Ocean Ranger oil rig capsized 267 km off the NL coast, killing all on board, the air rescue was coordinated 600 km away, from the town of Gander.2 NL's rural practitioners consult with urban specialists for routine and elective cases, sometimes using technologies like radio, telemedicine and now the internet.3 The frequency of these communications remains unknown. Previous studies describe telecommunication tools that can be used synchronously or asynchronously, from oil rigs,4 polar regions,5 and developing countries.6 While little data describes asynchronous communication between doctors, evidence suggests that some telecommunications may not transmit the subtle non-verbal cues that modify face-to-face conversations and provide emotional context7–11 between doctors and their patients.12–14

Miscommunication between family doctors and specialists is common in urban contexts.15 It disrupts collaborative relationships, exacerbates a perceived hierarchical imbalance, and threatens trust.15 Most important, it has a serious negative impact on patient safety.16 The Canadian Patient Safety Institute identifies communication and teamwork failures as leading causes of adverse incidents,16 and the Joint Commission on Patient Safety identifies improving staff communication as a national patient safety goal.17 Ineffective communication also worsens rural isolation. It is difficult to recruit and retain physicians to the countryside where access to investigations is limited, there are few, if any, nearby specialists, and the family physician must constantly be available.18 19 These are the characteristics of a rural generalist culture. By contrast, the urban specialist culture is typically technology-driven and disease-focused.18 Urban specialists are better able than their rural family physicians to set their boundaries by deflecting or declining consultations.18 While 60% of communication failures within urban physician populations involve confusion or outright conflict,17 there has been little work comparing urban physicians with their country colleagues. Understanding the perspectives of communicating parties and evaluating perceived communication barriers are effective strategies for improvement.15 18 20 21 Research on urban emergency department consultations and handovers illuminates key themes underpinning conflict,20–22 and suggests that shared Electronic Medical Record (EMR) and standardised communication protocols may be useful.23 Our objective was to examine perceived communication barriers between rural family physicians and urban specialists in NL.

Methods

Employing an inductive approach, this mixed-methods survey design used purposive multilevel sampling to identify and describe perceived communication barriers between rural family physicians and urban consultants in NL. Two surveys were developed for this study. The questions were developed in consultation with content experts in emergency/rural medicine, and medical education research. The surveys included both closed and open-ended questions. Adhering to the principles of triangulation, the qualitative data were analysed by three researchers over the course of several months.

Setting

Our study was conducted in Newfoundland, a North Atlantic island that, together with subarctic continental Labrador, forms one Canadian province. Its smallest town has only five residents,24 while the largest has 214 285 as of 1 July 2015. Only 1301 physicians practice in the 30 health centres or hospitals25 that are spread throughout NL. There are three tertiary care centres in the capital city, St. John's. Sixty per cent of NL inhabitants fulfil one definition of rurality26 by not living near a city of 50 000 or more.27 Small isolated fishing communities sit along NL's 17 540 km-long coast. Remote presence robotics are used in parts of Labrador for patient consultations, for guiding real resuscitations and for teaching simulated ones.28

The official languages spoken in Newfoundland are English and French; however, 95.3% of the population speaks solely English.29

Participants

Participant inclusion criteria was self-identification as either (1) a practicing family physician in rural Newfoundland and Labrador, or (2) a practicing internal medicine or surgery consultant in the provincial urban referral centre in St John's, NL. In rural NL, family physicians provide routine emergency and transport care. Our rural respondents came from a wide array of communities across the province, ranging from Happy Valley Goose Bay in Labrador to Bell Island, a small island off the east coast of NL.

Data collection

Rural physicians and urban consultants were sent two complementary Fluid Survey questionnaires, each asking the other about their perceived communication experiences. Urban consultants were recruited from internal medicine and surgery via departmental email lists. Rural physicians were recruited via email and in person from the rural preceptors meeting in NL. The surveys were distributed through purposive sampling to achieve comparability between the online and paper formats. Both surveys included Likert-type and open-ended questions, such as those in online supplementary appendices 1 and 2.

bmjopen-2015-010153supp_appendix1.pdf (111.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010153supp_appendix2.pdf (111.7KB, pdf)

There were no risks identified in participating in this research. The research team was committed to ensuring confidentiality for participants. The Interdisciplinary Committee on Ethics in Human Research at Memorial University of Newfoundland approved this research project.

Analyses

Comparative statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc for Windows, V.12.5 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). The qualitative analysis involved coding and analysing the open-ended responses for key themes. A thematic content analysis was systematically conducted first manually and second using Nvivo10 software. Multiple researchers (DW, SA, CH) independently coded the data and iteratively reviewed it until saturation was achieved. Analytic rigour was ensured through triangulation of both methods and researchers, and by searching for conflicting or atypical commentary. Quotations from participant responses are presented to increase trustworthiness of the research findings.

Results

A total of 75 participants from 21 communities across NL completed the survey, including 52 rural physicians (29 men and 23 women) and 23 urban consultants (12 men, 11 women).

Of the 58 rural preceptors at the rural preceptors meeting, 37 completed our survey, for a response rate of 63.7%. A further 15 rural physicians and 23 urban consultants completed the survey online. Urban consultants were recruited from general and subspecialty surgery and internal medicine (see table 1).

Table 1.

Medical specialties represented by urban consultants

| Specialty | Number of urban consultants (n=23) | Percentage of urban consultants |

|---|---|---|

| General surgery | 7 | 30.4 |

| Internal medicine | 3 | 13.1 |

| Nephrology | 2 | 8.70 |

| Plastic and reconstructive surgery | 2 | 8.70 |

| Vascular surgery | 1 | 4.35 |

| Orthopaedic surgery | 1 | 4.35 |

| Gastroenterology | 1 | 4.35 |

| Urology | 1 | 4.35 |

| Orthopaedics | 1 | 4.35 |

| Infectious diseases | 1 | 4.35 |

| Ophthalmology | 1 | 4.35 |

| Endocrinology | 1 | 4.35 |

| Oncology | 1 | 4.35 |

Quantitative results

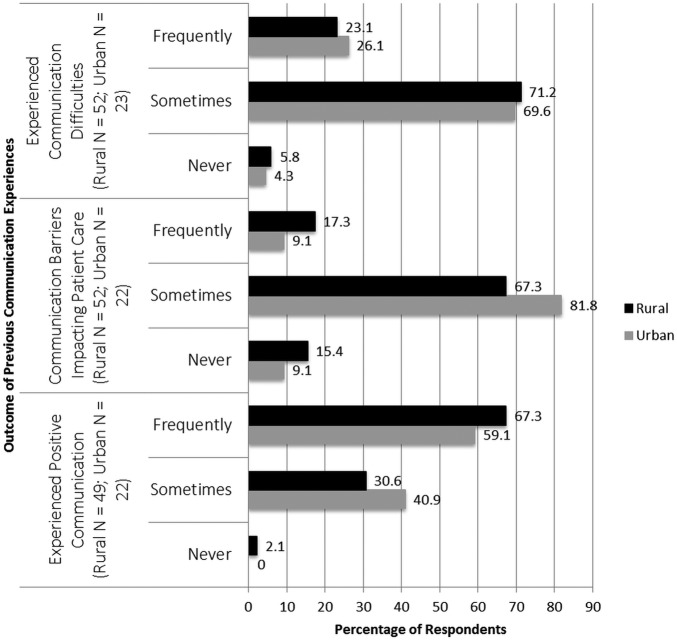

Of our 75 respondents, 69.3% were rural family practitioners and 30.7% were urban consultants. Seven per cent of rural practitioners had prior urban practice experience. Overall, 94.7% of participants perceived communication difficulties with one another, and 85.3% of participants indicated that this impacted patient care. Ninety-nine per cent of participants, and all urban specialists, perceived at least occasional smooth communications. Figure 1 shows a breakdown of the Likert scale scores to questions about previous communication experience. Three rural respondents did not complete this component of the survey.

Figure 1.

Percentage of rural family physicians and urban specialists indicating communication difficulties, communication barriers impacting patient care, and good communication experiences.

Qualitative results

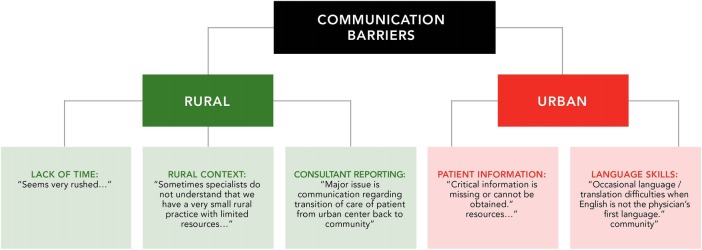

We asked participants to illustrate their perceived communication barriers when consulting with urban consultants. Their responses identified three primary themes: (1) time limitations, (2) misunderstanding of rural site limitations, and (3) inadequate reporting of results and summaries. More specifically, the rural family physicians in our study perceived that consultants often did not have time for them, noting that they ‘sometimes do not telephone promptly when on call’, and ‘lacked available (patient) appointments’. They also felt misunderstood by urban specialists who seem to be unaware of the context in which rural physicians work. For example, rural physicians stated that ‘(urban specialists) have no clue as to my context’, and ‘(the) consultant has no understanding of rural issues’. Finally, rural family physicians perceived that specialist reporting was sometimes inadequate or absent. Comments included: ‘Specialists sometimes do not provide appropriate management information’, and ‘there is no discharge summary’ (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Selected quotes from rural and urban physicians used in thematic analysis of communication barriers.

Conversely, urban specialists perceived (1) inadequate accompanying patient information and (2) native language barriers as obstacles to effective communication with rural family physicians. Illustrating the former perception, one specialist wrote, there was ‘poor history taking (and) inadequate examination of (the) patient’. Another simply stated ‘too little information given’. On perceived language barriers, specialists noted that ‘a language barrier (is) sometimes an issue’, and ‘language barriers, accents’ can impede communications.

Selected quotes are reported in figure 2.

Discussion

Principal findings

Quantitative: Nearly 95% of the physicians in our study perceived communication difficulties with their rural or urban counterparts. Almost all participants perceived at least one instance of turbulent communication, while about a quarter of rural and urban doctors perceived these difficulties on a regular basis. Furthermore, 67% of rural family physicians and 82% of urban consultants expressed that the barriers they perceived when communicating with one another had a negative impact on patient care. Interestingly, rural-to-urban communication appears to be as troublesome as urban-to-rural. These findings illustrate the importance of investigating and finding ways to address perceived communication barriers between these groups of doctors in NL, with a view to discovering how best to make improvements and optimise patient care.

That said, all but one participant also perceived positive communication during consultations, with the majority indicating that this happens frequently. This suggests that both urban and rural doctors can potentially communicate well together.

Qualitative: Our qualitative analyses helped to elaborate on, and provide examples of, the perceived communication barriers indicated above. Three themes described the rural family physicians' perceived communication barriers: (1) time constraints, (2) contextual misunderstanding and (3) poor reporting; while urban specialists' perceptions fell into two themes: (1) inadequate patient information and (2) language difficulties.

Barriers

Time limitations: Rural family physicians in our study perceived that urban consultants did not have time for them. Rushed consultations during inhospital handovers may impede clarification by discouraging questions, and may hinder read-back and answer-back strategies.30 Important information may be omitted under the pressure of time. Pertinent social or geographic information is time-consuming to relate, but it can help to shape an appropriate diagnostic or therapeutic approach. Take, for example, an elderly rural patient who needs to have a lung biopsy, but who will likely refuse the procedure both because her husband recently died of lung cancer, and because she lives far from the city. However, her rural family physician predicts that seeing the specialist will in itself establish the trust she needs to eventually consent to the biopsy. The specialist, while aware that rural travel can be inherently challenging, has, in the past, lost valuable new-patient appointment times to late cancellations. For this reason, he or she may be reluctant to place on an already long waitlist, a patient who is likely to decline the recommended diagnostic procedure. Effective communication between both physicians may help them to understand each other's contexts, and ultimately find mutually acceptable solutions. Previous research suggests that good communication grows from building strong relationships15 and sharing collegial activities,30 processes that might enable rural and urban physicians to better understand one another's perspectives, and find the best approach to this kind of consultation.

Telemedicine could improve access to consultants, though some studies refer to its often-overlooked subtractive communicative effects on healthcare practitioners and patients.12–14 Timeliness of consultations may be facilitated by secure messaging or shared EMR. Though such technologies may be useful for transmitting specific information, they may not relate well the ‘mental model’ of the patient,23 and may be less useful than narrative reporting in circumstances that call for a more customised approach.31 One study of EMR use between health workers reports problematically poor transmission of nuanced communication that may be more frequent than through other modes of discourse.32 The use of standardised referral processes and systemic improvements in consultation efficiency, while not examined in our study, may improve time management.

Contextual misunderstanding: Rural family physicians in our study perceived that urban consultants do not understand their context. Specialists working in an urban context are better able than their rural colleagues to define their boundaries and control their time. They may be unavailable for prompt consultation when on call, even in an emergency, and can divert or decline referrals. The patients involved still need medical care, which then falls to the rural physician. As one of few providers in a rural setting, he or she must be available. Unsure of their roles and responsibilities in this setting, family physicians report they are ‘left holding the bag’.18

Urban specialists in nearby referral hospitals sometimes refuse to accept patients because they have no available beds. To the rural family physician, this is like being at sea on a foundering boat, helplessly watching a cruise liner sail by with her full complement of shipboard physicians (Dr James Rourke, personal communication, October 2015).

Both groups of physicians may be influenced by their practice settings and patient populations,33 34 an inclination known as arrogant perception.30 This can lead diseased-focused and technology-driven urban specialists to overestimate the available emergency resources at rural hospitals, where, in fact, resuscitation capabilities are very basic. It may also cause them to mistakenly think their routine investigations and therapies are available in rural settings. Conversely, such perception may limit rural family physicians' familiarity with those same tests and treatments because they are impractical and, therefore, inapplicable to their own patient population. Arrogant perception may also cause rural family physicians to expect unrealistically prompt consultation (overlooking the myriad responsibilities the urban specialist must prioritise while taking referrals), and lead them to write overly succinct referral notes.

The two groups of physicians see their worlds through different lenses. This contextual polarity may add to the implicit sense of unmet expectations sometimes felt by rural family physicians working in isolation, highlighting the hidden curriculum or socialised attitudes that are hidden in plain sight rather than expressed explicitly. In medicine, we are taught to value inclusivity, to know everything. In practice, where book learning meets practicality, urban specialists need to have deep focused knowledge in a small area, while rural family physicians must operate very broadly. They evaluate specific diseases and undifferentiated illnesses in elective and urgent situations, while considering each patient's particular social milieu. The two approaches should be seen as complementary and of equal merit.

Judgemental attitudes between physician groups affects communication and may be mitigated by meeting together, clarifying expectations and providing feedback.30 These approaches may help to resolve contextual misunderstanding, negotiate appropriate access to tests, and modify feelings of rural isolation. Effective communication between rural family physicians and urban specialists may also help to remedy perceived imbalances in the medical hierarchy. In order to promote sustainable fundamental change, today's learners, who are also tomorrow's doctors, must be included in the discussion.

Patient information: That urban specialists in our study report receiving inadequate patent information, is thought-provoking in light of previous research suggesting that specialists are not interested in a referring physician's work-up, as they value their own investigation more.35 The situation brings to mind the oft-quoted adage: ‘sutures too long, sutures too short’. Standardised reporting mnemonics are available for transmitting patient information. One study reports they are infrequently used in intensive care unit (ICU) resident handoffs, however, partly because some patient information is specific to the individual.36 In handoffs between hospital services, information transfer may be affected by differences in each party's work patterns and expertise.23 The same may apply to rural–urban physician consultations. As discussed earlier, shared access to EMR and better referral systems may improve the transmission of patient information, as well as reporting and timeliness.

Reporting: The majority of our rural and urban respondents perceived that miscommunication adversely affected patient care. Research in an urban setting suggests that lack of communication affected the quality of patient care in 25% of follow-up visits.37 Rural family physicians and urban consultants in NL communicate by telephone, in writing (by hand and EMR), and sometimes telemedicine, but the province's rural patients may travel vast geographical distances to see an urban specialist. For example, the distance from Nain to the referral centre of Goose Bay, Labrador is 369 km via air. While remote-presence robotics are sometimes used for consultations in Nain, it is essential after physical visits that urban specialists clearly articulate relevant patient care recommendations to the rural family physician into whose care these patients return.

Language skills: A number of urban specialists noted they perceived language skills as a barrier to communication when dealing with rural family physicians. It is common for international medical graduates to practice in NL.38 As of October 2015, 36% of specialists and 36% of family physicians in the province, as well as 52% of the 343 rural family physicians, were international medical graduates.39 It is unknown how many of them whose native language or training is non-English. The College of Physicians of Surgeons of NL implemented language proficiency standards in 2011.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research on communication perceptions between rural family physicians and urban specialists. The study was from a single province and the sample size was small. Response rate was available from only the rural preceptors' meeting. We did not collect physician demographics or information about years of training and experience. Triangulation enhanced rigour, but our novel survey instrument lacked validity and reliability. Data about native language was not collected for either group. It emerged as a barrier on analysis of results.

Strengths and limitations compared to other studies

This study is the first examination of communication perceptions between urban specialists and rural family physicians. Urban studies describing communication barriers between city family physicians and specialists,15 18 37 40 as well as during hospital consultations and handovers,15 18 22 suggest that miscommunication is common, even between doctors working in the same centres.15 We discovered similar perceived communication barriers between doctors who work in urban and rural centres. The literature reports that in urban settings, miscommunication between groups of doctors arises both when information is lacking41 and when information is available but poorly handed over face-to-face.42 Our study suggests that time pressures, feelings of inferiority, contextual misunderstanding, inadequate reporting and language barriers may lead to perceptions of miscommunication. In the very special setting of isolated or polar regions, and in the developing world3–6 where technologies like radio, telemedicine and the internet are used for information transfer, limited emotional context and asynchronous communication may be particularly challenging.

Meaning of the study

Rural family physicians and urban consultants in NL perceive communication barriers with one another. We identified time pressures, contextual misunderstanding, reporting problems and language barriers as contributing factors. Improved communication strategies are likely to be multifactorial, involving systems improvement, as well as further mapping of the referral communication processes and media in NL. Education about communication is another potential solution. Knowledge of all these processes may be useful to help policy makers and researchers design quality improvement strategies.

Unanswered questions and future research

It is unknown whether our results from one province are transferrable to other remote islands of different size, population density and climate, or to offshore installations and ships. We do not know how synchronous and asynchronous distance communications affect information transfer. This initial study will inform future scholarship. Using qualitative methods, we plan to expand on initial findings, and examine multimodal solutions to the problems identified.

Conclusions

Medicine depends on good communication to ensure safety. Communication barriers are perceived between rural family physicians and urban consultants in NL. This study, based in the remote and isolated province of NL, may apply to communication perceptions in other similar environments.

Footnotes

Contributors: All listed authors have contributed significantly to this manuscript and meet the following criteria: Contributed to the conception and design of the work and/or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafted the work and/or revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the final version; agree to be accountable for all aspects of the manuscript in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Specifically, TR, AD, DW, CH and MP contributed to all parts of the paper. SA, CH and DW also contributed to the literature search. HC-T helped to write the results section. MM made significant contributions to the methods and results sections. All authors helped with design details, analysis and revision of the final document.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: ICEHR.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicals and Surgeons. CanMEDS 2005 Framework. http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/framework/the_7_canmeds_roles_e.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 2.Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board. Offshore Helicopter Safety Inquiry 2010. http://www.cnlopb.ca/pdfs/ohsi/ohsir_vol3.pdf (accessed Dec 2015).

- 3.Walsh C, Siegler E, Cheston E et al. , The Informatics Intervention Research Collaboration (I2RC). Provider-to-provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. 2013;8:589–97. 10.1002/jhm.2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mair F, Fraser S, Ferguson J et al. Telemedicine via satellite to support offshore oil platforms. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:129–31. 10.1258/jtt.2008.003008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lugg DJ. Telemedicine: have technological advances improved health care to remote Antarctic populations? Int J Circumpolar Health 1998;57(Suppl 1):682–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlein K, De La Cruz AY, Gopalakrishnan T et al. Private sector delivery of health services in developing countries: a mixed-methods study on quality assurance in social franchises. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:4 10.1186/1472-6963-13-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wootton R. Recent advances: telemedicine. BMJ 2001;323:557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roter D, Frankel R, Hall J et al. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:28–34. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00306.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jie X, Asan O, Montague E. A new method to evaluate gaze behavior patterns in doctor-patient interaction. Proc Hum Fact Ergon Soc Annu Meet 2011;55:485–9. 10.1177/1071181311551100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heath C. Pain talk: The expression of suffering in the medical consultation. Soc Psychol Q 1989;52:113–25. 10.2307/2786911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley V, Liddle S, Shaw R et al. Sticks and stones: investigating rude, dismissive and aggressive communication between doctors. Clin Med 2015;15:541–5. 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-6-541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roback K, Herzog A. Home informatics in healthcare: assessment guidelines to keep up quality of care and avoid adverse effects. Technol Healthc 2003;11:195–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Short L, Saindon E. Telehomecare rewards and risks. Caring 1998;17:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matusitz J, Breen G. Telemedicine: Its Effects on Health Communication. Health Commun 2007;21:73–83. 10.1080/10410230701283439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant I, Dixon A. Thank you for seeing this patient: studying the quality of communication between physicians. Can Fam Physician 1987;33:605–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Canadian Framework for Communication and Teamwork. http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/english/toolsresources/teamworkcommunication/documents/canadian20framework20for20teamwork20and%20communications.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 17.Joint Commission on Patient Safety. Hospital national patient safety goals. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2015_HAP_NPSG_ER.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 18.Manca DP, Breault L, Wishart P. A tale of two cultures: specialists and generalists sharing the load. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:576–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran V, Rourke J. The role of medical education in the recruitment and retention of rural physicians. Med Teach 2004;26:265–72. 10.1080/0142159042000192055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan T, Orlich D, Kulasegaram K et al. Understanding communication between emergency and consulting physicians: a qualitative study that describes and defines the essential elements of the emergency department consultation-referral process for the junior learner. CJEM 2013;15:42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan T, Bakewell F, Orlich D et al. Conflict prevention, conflict mitigation, and manifestations of conflict during emergency department consultations. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:308–13. 10.1111/acem.12325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler C, Chan T, Loeb J et al. I'm clear, you're clear, we're all clear: improving consultation communication skills in undergraduate medical education. Academic Med 2013;88:753–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MD, Hilligoss PB. Handoffs in Hospitals: A review of the literature on information exchange while transferring patient responsibility or control. 2009. http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/61498 (accessed Feb 2010).

- 24.Population and Dwelling Counts for Canada, 2011 and 2006 census-NL. Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/vc-rv/index.cfm?Lang=eng (accessed Oct 2015).

- 25.Newfoundland and Labrador Statistics Agency. Province of Newfoundland and Labrador: Location of hospitals and health centres. 2015. http://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/findhealthservices/maphospitalsandhealthcentres.pdf (accessed Dec 2015).

- 26.Du Plessis V, Beshiri R, Bollman R. Definitions of rural. Rural and small town Canada analysis bulletin. Statistics Canada, 2001. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/21-006-x/21-006-x2001003-eng.pdf (accessed Dec 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simms A, Greenwood R. Newfoundland and Labrador. State of Rural Canada 2015 2015. http://sorc.crrf.ca/nl/ (accessed Dec 2015).

- 28.Mendez I, Jong M, Keays-White D et al. The use of remote presence for health care delivery in a northern Inuit community: a feasibility study. Int J Circumpolar Health 2013;72:21112. 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Statistics Canada. Visual census—Language Newfoundland and Labrador 2011. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/vc-rv/index.cfm?Lang=ENG&VIEW=D&CFORMAT=jpg&GEOCODE=10&TOPIC_ID=4 (accessed Feb 2016).

- 30.Cady D. Moral vision: how everyday life shapes ethical thinking. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perrow C. Normal accidents: living with high-risk technologies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartswood M, Procter R, Rouncefield M. Making a case in medical work: implications for the electronic medical record. Comput Support Coop Work 2003;12:241–66. 10.1023/A:1025055829026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2014. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nichsr/hta101/ta101014.html (accessed Dec 2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Jelinek M. Spectrum bias: why generalists and specialists do not connect. Evid Based Med 2008;13:132–3. 10.1136/ebm.13.5.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams PT, Peet G. Differences in the value of clinical information: referring physicians versus consulting specialists. J Am Board Fam Physicians 1994;7:292–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ilan R, LeBaron C, Christianson M et al. Handover patterns: an observational study of critical care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. J Am Med Assoc 2007;297:831–41. 10.1001/jama.297.8.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rourke J. Increasing the number of rural physicians. Can Med Assoc J 2008;178:322–5. 10.1503/cmaj.070293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inkpen L. An overview of our physician population in Newfoundland and Labrador. (Oral presentation). Memorial University, Dean of Medicine, Stakeholders Meeting on Rural Recruitment and Retention. St. John's, NL, Canada, 2015.

- 40.Sijstermans R, Jaspers M, Bloemendaal P et al. Training inter-physician communication using the Dynamic Patient Simulator. Int J Med Inform 2007;76:336–43. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tingle J. Safety of clinical systems: Health Foundation finds cause for concern. Br J Nurs 2011;20:517–18. 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.8.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gardner R, Choo E, Gravenstein S et al. Why is this patient being sent here?: Communication from urgent care to emergency department. J Emerg Med 2016;50:416–21. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010153supp_appendix1.pdf (111.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010153supp_appendix2.pdf (111.7KB, pdf)