Abstract

Objective

Proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) has been implicated in inflammatory articular pathology. Using the collagen-induced arthritis model (CIA) the authors have explored the capacity of PAR2 to regulate adaptive immune pathways that could promote autoimmune mediated articular damage.

Methods

Using PAR2 gene deletion and other approaches to inhibit or prevent PAR2 activation, the development and progression of CIA were assessed via clinical and histological scores together with ex vivo immune analyses.

Results

The progression of CIA, assessed by arthritic score and histological assessment of joint damage, was significantly (p<0.0001) abrogated in PAR2 deficient mice or in wild-type mice administered either a PAR2 antagonist (ENMD-1068) or a PAR2 neutralising antibody (SAM11). Lymph node derived cell suspensions from PAR2 deficient mice were found to produce significantly less interleukin (IL)-17 and IFNγ in ex vivo recall collagen stimulation assays compared with wild-type littermates. In addition, substantial inhibition of TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β and IL-12 along with GM-CSF and MIP-1α was observed. However, spleen and lymph node histology did not differ between groups nor was any difference detected in draining lymph node cell subsets. Anticollagen antibody titres were significantly lower in PAR2 deficient mice.

Conclusion

These data support an important role for PAR2 in the pathogenesis of CIA and suggest an immunomodulatory role for this receptor in an adaptive model of inflammatory arthritis. PAR2 antagonism may offer future potential for the management of inflammatory arthritides in which a proteinase rich environment prevails.

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a progressive inflammatory arthropathy associated with substantial vascular comorbidity and thereby increased mortality.1 Therapeutic interventions via aggressive use of conventional and biologic disease modifying agents have significantly improved outcomes but unmet clinical need remains manifest in low remission rates and significant partial or non-responder subpopulations.2,3 A key learning point from such studies has been the pivotal role played by cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-6 in disease pathogenesis. It is therefore critical to elucidate those upstream factors that regulate cytokine production. Increasingly, elements of both innate and adaptive immunity are implicated in RA pathogenesis; for example, genome-wide scans implicate genes regulating T cell and B cell activation and novel therapeutics targeting co-stimulation and B cells suppress disease. Signal pathways that modulate cytokine production are also implicated. Collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) comprises a polyarthritis in genetically susceptible mice induced by immunisation with type II collagen, leading in turn to autoreactivity to autologous collagen with consequent downstream responses that include elaboration of effector cytokines,4-6 making this a suitable surrogate of RA for investigation of pathogenic mechanisms.

Proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) is one member of a recently discovered family of four cell surface G-protein coupled receptors which has significant roles in inflammation and the coagulation cascade.7,8 Previous studies have employed PAR2 deficient mice to implicate this receptor in articular inflammation.9-11 These findings translate to RA in humans since the selective PAR2 antagonist, ENMD-1068, significantly reduced basal release of TNFα and IL-1β from RA synovial tissues ex vivo.12 PAR2 is therefore identified as a novel upstream upregulator of pro-inflammatory cytokines, adding to the growing evidence implicating this receptor as a regulator of innate immune responses.13 It is less clear whether PAR2 regulates adaptive immune responses directly. PAR2 is expressed on dendritic cells (DCs),14 which could influence T cell dependent responses via cytokine regulation. We here report the impact of PAR2 deficiency or blockade upon modulation of arthritis induced by a predominantly adaptive immune challenge, namely CIA.

METHODS

Animals

Adult male DBA/1 mice (body weight ~25 g) were obtained from Harlan (Loughborough, UK), housed in standard plastic cages with food (rodent chow 5001) and water available ad libitum, and maintained in a thermoneutral environment (21±2°C) with 12-h light/dark cycles. PAR2 deficient mice (PAR2−/−) and wild-type littermates (PAR2+/+) on the C57Bl/6J background were generated as previously described.9 All procedures were performed in accordance with current UK (Home Office) regulations.

Induction of CIA

In view of the known relative resistance to CIA of C57Bl/6J mice compared with the DBA/1 strain, different protocols were employed for each strain. In DBA/1 mice (8–10 weeks old), lyophilised bovine type II collagen (MD Biosciences, Zurich, Switzerland) was dissolved at 2 mg/ml in 0.05 M acetic acid by gently stirring overnight at 4°C. Immediately prior to induction injections (day 0) the collagen solution and Freund’s complete adjuvant (FCA), containing 2 mg/ml heat killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (H37ra, BD Diagnostics, Oxford, UK), were used to prepare a 1:1 emulsion. The emulsion is prepared by adding collagen to FCA dropwise while mixing at low speed in an ice water bath. Solutions and emulsion were kept chilled at all times during mixing and prior to injections. These mice received 2×50 μl intradermal injections of the collagen:FCA emulsion at the base of the tail, that is, 100 μg collagen per animal. Booster injections of 100 μl collagen solution made up 1:1 with 2 mg/ml collagen (in acetic acid) and 0.9% NaCl were given intraperitoneally at day 21. In all, 80% incidence was achieved by day 30 with >80% of animals showing evidence of disease by day 35.

For mice on the C57Bl/6J background a modification of the protocol described by Inglis et al15 was used. Arthritis was induced at 14 weeks. Briefly, 1 mg/ml type II chicken collagen (MD Biosciences, Zurich, Switzerland) in FCA containing 2 mg/ml heat killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis as described above. Mice received 4×50 μl intradermal injections of the collagen:FCA emulsion at the base of tail, that is, 200 μg chicken type II collagen per animal. At day 21 postimmunisation, mice received a 100 μl intraperitoneal injection of 200 μg chicken collagen prepared in 0.9% NaCl. Mice were then checked daily to assess clinical scores.

Direct assessment of the inflammatory response was by means of an arthritis index,16 modified by extending the scale to a maximum of four per paw (supplementary table 1). Animals were terminated after treatment and the draining lymph nodes (LNs) and paws harvested for analysis. As arthritis incidence in the C57Bl/6J strain can be as low as 50%,15 only mice showing disease activity (defined as an arthritic index ≥1) were included in the analyses. To maintain consistency, this rule was also applied to the DBA/1 strain.

Histological analysis

Histological preparation involved harvesting paws, fixing o/n in 10% neutral buffered formalin followed by decalcification in 14% EDTA (pH8) at room temperature, with the EDTA solution changed every 2/3 days for a period of 14 days. Joints were embedded in paraffin wax and frontal sections (6 μm) cut followed by staining with H&E (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK). Images were digitally captured using a Carl Zeiss AxioCamERc5s camera and an AXIO Lab.A1 microscope.

For each animal, six high power fields were examined and scored by two observers blinded to genotype or treatment. The severity of arthritic changes, in terms of inflammatory cell infiltrate and cartilage damage, was scored on a 0–3 scale for each hind paw and a total score calculated. The scores from the two observers were in close agreement (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.9, 95% CI 0.95 to 0.80) and a mean of their scores is presented.

LN culture

LN cells were collected 5 days after arthritis onset (defined as an arthritic index ≥1) from PAR2−/− mice and wild-type littermates and a single cell suspension prepared. Cells were cultured at 2×106/ml in RPMI-1640 supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, glutamine, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% foetal bovine serum, in the presence or absence of 50 μg/ml heat denatured chicken type II collagen (65°C for 30 min), in a final volume of 200 μl. Incubation of LN cells with plate bound αCD3 (2 μg/ml) and soluble αCD28 (5 μg/ml; both from eBioscience, Hatfield, UK) were included as positive controls. After 48 h culture, supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until they could be analysed for cytokines and chemokines.

In addition, LN single cell suspensions from PAR2−/− mice and wild-type littermates were also stained for CD11c, F4/80, CD4, CD8 and CD19 populations using commercially available fluorochrome labelled antibodies (eBioscience, UK). Briefly, cells were incubated in fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (PBS/0.1% foetal bovine serum) and Fc block (antimouse CD16/32; eBioscience, UK) at 4°C for 10 min, prior to the addition of antibodies. The incubation was continued at 4°C for a further 30 min. Cells were washed in FACS buffer by centrifugation (150 g for 5 min at 4°C) prior to being resuspended in FACS buffer and 1% paraformaldehyde solution. Samples were then analysed using a BD FACS Calibur and Flowjo 7.2.5 (TreeStar, Oregon, USA).

Cytokine and chemokine analysis

Supernatants from LN cultures were initially assayed for TNFα by ELISA (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). All other analytes were assayed using a mouse 20-plex kit (Invitrogen, UK) as per manufacturer’s instructions and plates were read on a Luminex 100 system.

Analysis of serum anticollagen antibody titres

Serum was collected from responding mice (5 days post-disease onset) and used to analyse collagen specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibody titres, as outlined in supplementary methods.

Agents

ENMD-1068 (N1-3-methylbutyryl-N4-6-aminohexanoyl-piperazine) is a small molecule PAR2 antagonist which we have previously shown can inhibit carrageenan-induced joint inflammation.10 Although lacking potency, ENMD-1068 is selective even at high concentrations as it inhibits PAR2 mediated vasodilatation but has no effect on vasodilation induced by either PAR1 or PAR4. It also has no effect on acetylcholine mediated vasodilatation and, unlike some PAR2 antagonists, has no partial agonist activity (see supplementary figure 1). We previously showed that the monoclonal antibody SAM11 (sc13504, Santa Cruz Biotech, California, USA), directed to the sequence SLIGKVDGTSHVTG on the N terminus of the receptor, can also be used to block PAR2 mediated acute joint inflammation.11

Treatments

Postdisease onset (arthritis score ≥1) mice were treated daily by subcutaneous injection of 4 or 16 mg ENMD-1068 in 100 μl 0.9% saline at neutral pH (neutralised with 1M NaOH), or 0.9% saline vehicle alone, for 7 days and the progression of arthritis was monitored daily. In a separate group of DBA/1 mice, SAM11 or IgG2a control antibody was administered intraperitoneally, with a10 μg loading dose on day 1 of response followed by 1 μg daily dose given thereafter.

Statistics

Data were analysed using Sigmastat 2.03 (SPSS, California, USA) and are expressed as mean±SEM. Comparisons were performed using the two-tailed Student t test or one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) as appropriate, post hoc testing being performed using the Bonferroni correction. Where data were non-normally distributed, log10 transformation was performed prior to parametric analysis.

RESULTS

PAR2 deficiency is protective in murine CIA

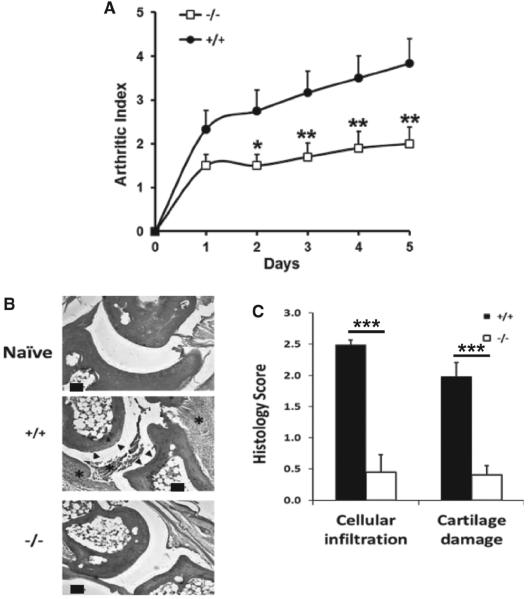

C57Bl/6J wild-type mice developed arthritis with an incidence of approximately 60% by day 35 postinduction and exhibited a progressive increase in the arthritis index (figure 1A), commensurate with prior reports using this model strain.15 In contrast, although PAR2−/− mice developed arthritis with similar incidence to wild type controls, the severity of disease was substantially reduced in comparison when judged by clinical assessment (arthritis index; p<0.0001, two-way ANOVA; n=10–12). Histological analysis of the paws revealed that wild-type mice showed cartilage erosion and inflammatory cellular infiltration, but appearances in PAR2−/− mice were similar to naïve mice (figure 1B), and for both of these parameters scored significantly (p<0.0001, t test; n=6–7) lower for severity than the wild-type (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) Arthritis index comparing wild-type (n=12) and PAR2−/− (n=10) mice following development of CIA. The groups differ significantly by two-way ANOVA (see Results section) and post hoc analysis (Bonferroni) showed differences from day 2 after disease onset (*p<0.05; **p<0.02). (B) Histological appearance of joints from the paws of naïve mice (top panel) compared with wild-type (middle panel) and PAR2−/− mice (bottom panel) stained with H&E. Asterisk denotes cellular infiltrate and arrows indicate cartilage erosion. Scale bar=100 μm]. (C) Histopathological scores comparing PAR2 deficient (n=6) and wild-type (n=7) mice. ***p<0.0001.

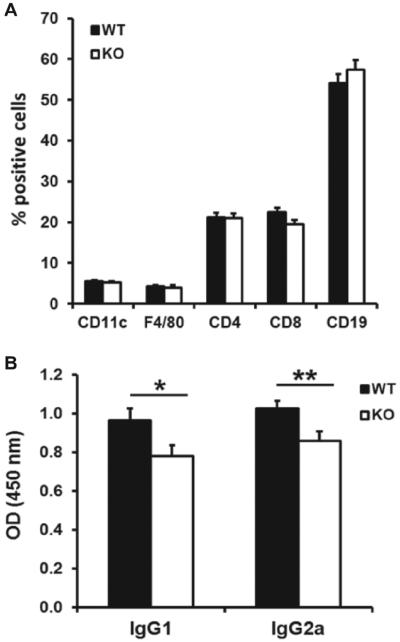

Histological examination of lymphoid organs revealed no significant structural or organisational differences between wild-type or PAR2−/− mice (supplementary figure 2), and FACS analysis of LN cell subsets showed similar population distributions of CD11c, F4/80, CD4, CD8 and CD19 in both groups of mice (figure 2A). However, examination of IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies revealed that PAR2−/− mice had modestly, but significantly, lower titres than wild-type (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) FACS analysis of draining LN cell subsets, showing no significance differences between groups (n=7–8) 5 days following development of arthritis. (B) Anticollagen antibody titres were significantly lower in PAR2−/− compared with wild-type mice (*p<0.05; **p<0.02).

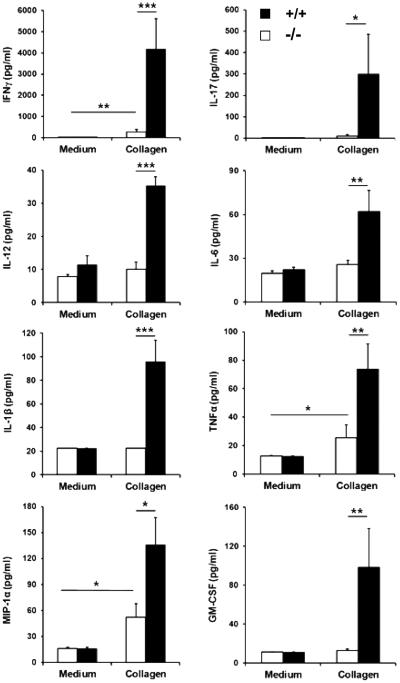

Analysis of cytokines and chemokines in supernatants from cultured LN cells suspensions incubated with collagen showed significant differences in the recall response between wild-type and PAR2−/− mice, particularly striking in respect of IFNγ and IL-17, these being substantially lower in the latter mice (figure 3). Interestingly, significant differences in TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12p40/70 along with MIP-1α and GM-CSF were also observed in these cultures (figure 3). These differences could not be explained by changes in the LN cellular composition exhibited in PAR2−/− and wild-type mice (figure 2B), suggesting that the differences in cytokine production reflected a functional rather than quantitative phenomenon. Similarly, responses to antiCD3/antiCD28 did not differ significantly between wild-type and PAR2−/− mice, indicating no alteration in cell viability and capacity to function after in vitro culture. LN cells from wild-type and PAR2−/− mice did not secrete detectable levels of IL-1α IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, VEGF, MCP-1, MIG, IP-10, KC and FGF in response to stimulation with collagen in vitro. They did, however, make detectable levels of IL-2, IL-5 and IL-13 in cultures stimulated with αCD3/αCD28 although these did not differ significantly between groups (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Panels indicate concentrations of cytokines and chemokines found in supernatants from lymph node cultures derived from PAR2−/− (white bars, n=8) and wild-type (black bars, n=8) mice 5 days after disease onset, as indicated by an arthritis score ≥1. ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

Targeting PAR2 is an effective therapeutic intervention in murine CIA

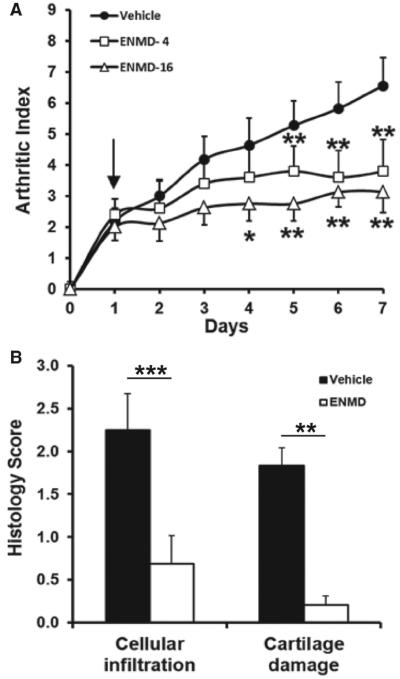

Having established that PAR2 could play an immune regulatory role in an adaptive model of arthritis, subsequent studies were restricted to establishing proof of concept for this receptor as a novel therapeutic target in this model. Induction of CIA in DBA/1 mice (performed to allow assessment of exogenous PAR2 inhibitors) was associated with development of signs of arthritis that were progressive in animals treated with vehicle for up to 7 days. In contrast, animals treated with 16 mg of ENMD-1068 did not show disease progression manifest in the clinical score. Recipients of 4 mg of this compound exhibited an intermediate phenotype suggesting dose responsive inhibition (figure 4A). Both the 4 and 16 mg doses differed from vehicle (p<0.00001 for both, Bonferroni correction) but did not differ from each other. Histopathological analysis demonstrated that in a subset of mice treated with 16 mg ENMD-1068, there was significantly less cellular infiltration (p<0.005, t test) and cartilage damage (p<0.0002, t test) compared with vehicle treatment (figure 4B). Inflammatory hyperaemia of the paw, assessed by laser Doppler imaging, was also attenuated in mice treated with ENMD-1068 (supplementary figure 3).

Figure 4.

(A) Articular index in wild-type DBA/1 mice administered saline vehicle (n=11), or ENMD-1068 at 4 mg (n=5) and 16 mg (n=8) by daily subcutaneous injection after disease onset (arrow). The arthritis score is reduced by treatment at both doses (see two-way ANOVA in Results section). Post hoc analysis showed differences from day 4 after disease onset (*p<0.05; **p<0.01). (B) Histopathological scores differed significantly between mice treated with vehicle and 16 mg ENMD-1068 for both inflammatory cell infi ltrate and cartilage damage. ***p<0.0001; **p<0.01, t test, n=4–8.

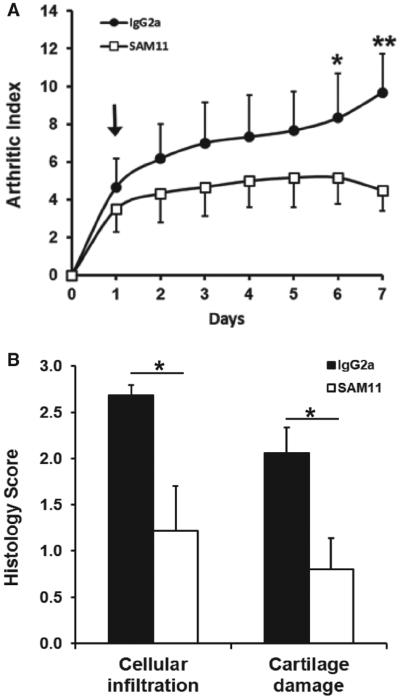

Essentially, similar results were obtained in this strain of mice using the PAR2 antibody SAM11, namely significant (p=0.017, 2-way ANOVA, n=6) reduction in arthritic (figure 5A) and histological damage (figure 5B) scores compared with isotype IgG2a control antibody.

Figure 5.

(A) Compared with wild-type treated with control antibody (IgG2a), DBA/1 mice given daily intraperitoneal injection of the PAR2 neutralising monoclonal antibody SAM11 after disease onset (arrow) show reduced arthritis index, post hoc analysis showing signifi cant differences by day 6 (*p<0.05; **p<0.01). (B) Scores for both inflammatory cell infi ltrate and cartilage damage were lower in SAM11 treated mice compared with control IgG2a antibody.*p<0.05, t test, n=6 in each group.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to demonstrate that either genetic deletion of PAR2 or therapeutic intervention can substantially inhibit collagen-induced murine arthritis. We previously found that disease severity in an innate immune driven model of arthritis (FCA monarthritis) was substantially abrogated in PAR2−/−mice.9 The current study advances our earlier work by identifying an important role for PAR2 in a more clinically relevant model of arthritis, namely one characterised by having an adaptive immune response.

PAR2−/− mice had reduced arthritic and histological damage scores compared with wild-type littermates. The lower incidence and magnitude of response to CIA in the C57Bl/6J strain is widely recognised, and while severity and progression were reduced in PAR2−/− mice compared with wild-type, no difference in incidence was noted between groups in the present study. Importantly, substantial reduction in antigen recall induced cytokine and chemokine production by LN cultures, particularly IFNγ and IL-17, was observed. This is consistent with PAR2 modulating T helper cell (Th)1 and Th17 responses, thereby influencing immunological response to antigen challenge. Whether this is a direct or indirect effect of PAR2 on the adaptive immune response remains unclear and is not tested in the current experimental model. LN from PAR2−/−mice stimulated with collagen secreted reduced levels of IL-1β and IL-6, cytokines known to be important in Th17 polarisation of cells,17,18 while a reduction in the Th1 polarising cytokine, IL-12,19 was also observed. If in vivo polarisation is altered in PAR2−/− mice, this would provide one explanation for the reduced IFN γ and IL-17 observed in the cultures. It is however of note that both human and mouse T cells are capable of expressing PAR220 and, moreover, cytokine regulation via PAR2 signalling has been demonstrated.20,21 It is therefore also possible that PAR2 expressed on T cells may have a direct influence on T cell phenotype and function in vivo which would consequently impact on IL-17 and IFN γ production. While this hypothesis requires additional investigation, we would suggest that our data demonstrate a role for PAR2 in immune regulation in an adaptive model of arthritis, although the precise mechanism is unclear at present. Potentially this could involve modulation of DC function as DCs derived from the bone marrow of PAR2 deficient mice release significantly less IL-6, IL-23 and TNFα compared with cells from wild-type mice on exposure to serine protease.22 Furthermore, a PAR2 activating peptide significantly increased the frequency of mature CD11chigh DCs in draining LNs and led to these cells showing increased expression of major histocompatibility complex class II and CD86 in wild-type but not PAR2−/− mice.23 However, these authors observed no significant difference in the proportion of CD11c cells in LNs of naïve wild-type and PAR2−/− mice. Similarly, we observed no change in the CD11c population from LNs of wild-type and PAR2−/− mice following induction and development of CIA. However, while the DC numbers may not appear altered, their maturation status and cytokine profile may differ and as such this represents an area for future investigation.

Having established proof of concept in the PAR2−/− mouse studies, we then investigated the potential of therapeutic intervention by targeting PAR2. Therapeutic administration of the PAR2 antagonist (ENMD-1068) potently inhibited progression of CIA compared with vehicle-treated mice. The arthritis index was dose-dependently reduced in animals treated with ENMD-1068. Histological analysis of peripheral joints corroborated these findings, both cellular infiltrate and joint damage being substantially lower in treated mice. Parallel findings were obtained in wild-type mice administered the PAR2 monoclonal antibody SAM11 which showed reduced disease activity compared with mice given isotype control antibody. As a pilot study, inflammatory hyperaemia, assessed non-invasively using laser Doppler imaging, was also reduced in animals treated with ENMD-1068. Taken together, this study argues for an immunomodulatory role for PAR2 in the pathogenesis of an adaptive immune model of arthritis, even when inhibition is delayed until after the onset of disease. The present report supports our previous observations9 and suggests a role for PAR2 in both innate and adaptive immune-driven arthritic disease processes.

CIA is widely recognised as the ‘gold standard’ experimental model for investigation of RA and adaptive immune responses. Our findings that both PAR2 deficiency and therapeutic inhibition ameliorate disease demonstrate a pathogenic role for PAR2 in inflammatory joint disease. This is supported by the finding of Busso and colleagues11 who reported that PAR2 deficiency reduced disease activity in antigen-induced monarthritis. Although they were unable to confirm our earlier finding that FCA monarthritis was substantially reduced in PAR2 deficient mice,9 this is likely related to differences in induction protocol on which the magnitude of chronic inflammatory response is critically dependent. An effective chronic inflammatory response is ensured by a combination of intra-articular and peri-articular injection of FCA.24,25 The simpler protocol used by Busso et al11 involved using a single intra-articular injection which produces a much smaller inflammatory response.11,24 This, coupled with the residual inflammatory response we observed in PAR2 knock-out mice,9 would have made it difficult to distinguish between wild-type and PAR2 deficient mice in the Busso study.11 This likely explains the difference in result and conclusion between these two studies.9,11

It is possible that, acting as a proteinase sensor, PAR2 may form part of an ‘alarmin’ system operating via innate mechanisms to drive subsequent adaptive responses. Consistent with this is the growing recognition that PAR2 has important roles in both innate and adaptive immunity (for review see 13). The nature of the endogenous proteinases released in LN cultures and which could activate PAR2 is unknown at present. However, it has been shown that DCs show a variety of proteinase activities including cathepsins and trypsin-like proteinases.26 Macrophages in the LN are known to express a serine proteinase with tryptase-like homology.27 Similarly, B cells are known to show trypsin-like serine proteinase activity.28

PAR2 has relevance to human disease as it is found in CD68 cells within the synovium of RA patients11,12 and its synovial expression is strongly correlated with inflammatory indices.29 Furthermore, surface expression of PAR2 is upregulated on CD3 and CD14 cells in RA patients compared with healthy individuals.30 While these observations alone cannot determine the role of PAR2 in the pathogenesis of RA, a pro-inflammatory role is indicated by our observation that ENMD-1068 potently inhibited TNFα and IL-1β release from rheumatoid synovial membrane ex vivo.12

Orally active small molecular weight compounds obviate many of the difficulties of administration associated with current biologic agents, and there is increasing interest in developing such compounds with anti-inflammatory activity, particularly those that might act upstream of existing biologic validated targets. ENMD-1068 shows considerable potential in terms of molecular size and anti-inflammatory action and retains PAR2 selectivity even at high concentrations (see supplementary figure 1). ENMD-1068 therefore provides a powerful proof of concept for therapeutic targeting of PAR2. That said, this agent has low potency precluding useful therapeutic development. However, newer PAR2 antagonists have recently been developed,31,32 and although potency is still suboptimal, future leads may yield compounds suitable for clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marion Drew for technical assistance and Peter Kerr for processing histological specimens. This work was supported by Entremed, University of the West of Scotland studentship (HSP), the Scottish Biomedical Foundation and Arthritis Research UK (18306).

Funding Provided by Arthritis Research UK.

Footnotes

Contributors Design: AC, HP, MN, JL, RP, IM, WF. Experimentation: AC, HP, MN, LD, RP. Analysis: AC, HP, LD, JL, WF. Manuscript preparation: AC, HP, MN, JL, IM, WF.

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement We aim to publish our findings in quality, high impact peer reviewed journals preferably with open access; this may be limited by any potential intellectual property issues (see below). Any supplementary data that cannot be published will be available after a certain period either to bona fide request to the PI/Co-PIs or by downloading from University web profile pages. When permitted, publications will be added to the University of Glasgow repository (Enlighten; https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/). All data are routinely stored electronically as well as in hard copy format, and data are stored for at least 7 years and are available for scrutiny.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sattar N, McCarey DW, Capell H, et al. Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;108:2957–63. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099844.31524.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castro-Rueda H, Kavanaugh A. Biologic therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: the latest evidence. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:314–9. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282f5fcf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372:375–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RO. Collagen-induced arthritis as a model for rheumatoid arthritis. Methods Mol Med. 2004;98:207–16. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-771-8:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McInnes IB, Schett G. Cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:429–42. doi: 10.1038/nri2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldmann M, Maini SR. Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis: an education in pathophysiology and therapeutics. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:7–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macfarlane SR, Seatter MJ, Kanke T, et al. Proteinase-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:245–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollenberg MD, Compton SJ, International Union of Pharmacology. XXVIII Proteinase-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:203–17. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrell WR, Lockhart JC, Kelso EB, et al. Essential role for proteinase-activated receptor-2 in arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:35–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI16913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelso EB, Lockhart JC, Hembrough T, et al. Therapeutic promise of proteinase-activated receptor-2 antagonism in joint infl ammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1017–24. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busso N, Frasnelli M, Feifel R, et al. Evaluation of protease-activated receptor 2 in murine models of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:101–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelso EB, Ferrell WR, Lockhart JC, et al. Expression and proinflammatory role of proteinase-activated receptor 2 in rheumatoid synovium: ex vivo studies using a novel proteinase-activated receptor 2 antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:765–71. doi: 10.1002/art.22423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shpacovitch V, Feld M, Hollenberg MD, et al. Role of protease-activated receptors in inflammatory responses, innate and adaptive immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1309–22. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fields RC, Schoenecker JG, Hart JP, et al. Protease-activated receptor-2 signaling triggers dendritic cell development. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1817–22. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64316-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inglis JJ, Simelyte E, McCann FE, et al. Protocol for the induction of arthritis in C57BL/6 mice. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:612–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei XQ, Leung BP, Arthur HM, et al. Reduced incidence and severity of collagen-induced arthritis in mice lacking IL-18. J Immunol. 2001;166:517–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, et al. TGFbeta in the context of an infl ammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung Y, Chang SH, Martinez GJ, et al. Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by interleukin-1 signaling. Immunity. 2009;30:576–87. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manetti R, Parronchi P, Giudizi MG, et al. Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin 12 [IL-12]) induces T helper type 1 (Th1)-specific immune responses and inhibits the development of IL-4-producing Th cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1199–204. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li T, He S. Induction of IL-6 release from human T cells by PAR-1 and PAR-2 agonists. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:461–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2006.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shichijo M, Kondo S, Ishimori M, et al. PAR-2 deficient CD4+ T cells exhibit downregulation of IL-4 and upregulation of IFN-gamma after antigen challenge in mice. Allergol Int. 2006;55:271–8. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.55.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewkowich IP, Day SB, Ledford JR, et al. Protease-activated receptor 2 activation of myeloid dendritic cells regulates allergic airway inflammation. Respir Res. 2011;12:122. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramelli G, Fuertes S, Narayan S, et al. Protease-activated receptor 2 signalling promotes dendritic cell antigen transport and T-cell activation in vivo. Immunology. 2010;129:20–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelso EB, Dunning L, Lockhart JC, et al. Strain dependence in murine models of monoarthritis. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:511–4. doi: 10.1007/s00011-007-7058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrell W, Kelso E, Lockhart J, et al. Development of adjuvant monarthritis is critically dependent on the induction protocol: comment on the article by Busso et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3510. doi: 10.1002/art.22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohamadzadeh M, Mohamadzadeh H, Brammer M, et al. Identification of proteases employed by dendritic cells in the processing of protein purified derivative (PPD) J Immune Based Ther Vaccines 2004. 2004;2:2–8. doi: 10.1186/1476-8518-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C, Darrow AL, Qi JS, et al. A novel serine protease predominately expressed in macrophages. Biochem J. 2003;374:97–107. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biro A, Sarmay G, Rozsnyay Z, et al. A trypsin-like serine protease activity on activated human B cells and various B cell lines. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2547–53. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tindell AG, Kelso EB, Ferrell WR, et al. Correlation of protease-activated receptor-2 expression and synovitis in rheumatoid and osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2102-9. doi:10.1007/s00296-011-2012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crilly A, Burns E, Nickdel MB, et al. PAR2 expression in peripheral blood monocytes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jan 30; doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200703. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barry GD, Suen JY, Le GT, et al. Novel agonists and antagonists for human protease activated receptor 2. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7428–40. doi: 10.1021/jm100984y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suen JY, Barry GD, Lohman, et al. Modulating human proteinase activated receptor 2 with a novel antagonist (GB88) and agonist (GB110) Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:1413–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.