Abstract

A large body of literature suggests that aggressive behavior can be classified into two subtypes, reactive aggression (RA) and proactive aggression (PA), which differ on dimensions of emotional arousal, control, and impulsivity. A longstanding hypothesis posits that RA underlies the association between aggression and suicidal behavior, with the implicit assumption that PA is unrelated to suicidal behavior. However, no empirical study to date has specifically investigated this question. We examined associations of RA and PA with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation among 878 male and female patients in substance dependence treatment programs. We also examined the moderating effects of sex. Contrary to hypotheses, PA was associated with both suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. RA was also associated with both outcomes in unadjusted analyses, but became non-significant for suicide attempts in multivariate analyses. Moreover, sex served as a moderator, with PA showing an association with suicide attempt among men, but not women. Results indicate the need for additional studies of PA and suicidal behavior.

Aggression can be reliably classified into two subtypes: 1) an emotionally charged, poorly controlled, impulsive (reactive) type, or 2) an unemotional, highly controlled, premeditated (proactive) type (Houston, Stanford, Villemarette-Pittman, Conklin, & Helfritz, 2003). Proactive aggression (PA) is executed for a reward (e.g., to intimidate another individual) and is accompanied by low autonomic arousal and a lack of emotional awareness. Reactive aggression (RA) is associated with emotional arousal including anger and anxiety, poor modulation of physiological arousal, and a loss of behavioral control. Although not all researchers agree that the RA-PA distinction is useful (Bushman & Anderson, 2001), there is strong evidence for the RA-PA framework. Researchers have found consistent, inverse relationships between the neurotransmitter serotonin and RA. Additionally, studies of neuropsychological functioning, electrocortical function, neurocognitive processing, and positron emission tomography have documented that functional impairments are related to RA (Houston et al., 2003). These relationships have not been established with PA.

A longstanding hypothesis is that individuals with high levels of RA are at risk for suicidal behavior (Conner, Duberstein, Conwell, & Caine, 2003; Turecki, 2005). Much of the evidence is based on data that individuals with suicidal behavior exhibit serotonergic hypofunction, a marker for RA. These data include comparisons of brain tissue obtained postmortem showing that serotonin and its principal metabolite, 5-hydroxyindoleactic acid (5-HIAA), is lower in key brain structures among suicide decedents compared to non-suicides, and that postmortem receptor assays also support reduced serotonergic function in suicide. Studies of suicide attempters also show lower levels of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) 5-HIAA when compared with nonattempters (Mann, 2003; Turecki, 2005). Additionally, studies using personality measures generally support the idea that RA distinguishes individuals who attempt or die by suicide (Brezo, Paris, & Turecki, 2006).

However, the data on RA and suicidal behavior are not definitive. We are aware of no studies of suicidal behavior that have compared measures explicitly designed to measure RA versus PA. In particular, there is paucity of data on PA. Moreover, altered brain serotonin-mediated neurotransmission is not a specific indicator of RA. Although genetic studies keying on the serotonin transporter (5-HTT; 5-HTTLPR allele) polymorphism show an association with suicidal behavior (Lin & Tsai, 2004), the allele is also associated with negative affect (Schinka, Busch, & Robichaux-Keene, 2004), which may explain the association with suicidal behavior (van Praag, 2000).

The association of aggression and suicidal behavior may vary depending on the population studied. The current study focuses on individuals with substance use disorders. Their elevated risk for suicidal behavior (Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999) and violence (Pulav et al., 2008) suggests the importance of examining the link between aggression and suicidal behavior, yet there are limited data on different aspects of aggression in this population (Koller, Preuss, Bottlender, Wenzel, & Soyka, 2002). An analysis of a large sample of individuals with alcohol dependence provides preliminary support for the idea that RA is uniquely related to (impulsive) suicidal behavior (Conner et al., 2007a). The study showed that alcohol-related aggression was associated with unplanned (impulsive) suicide attempts but was not associated with other suicide-related outcomes (ideation, planning, or planned attempts). This finding highlights the importance of examining suicide attempts and suicidal ideation and their correlates separately, although the extent to which alcohol-related aggression taps RA is unclear.

Using a sample of individuals in treatment for substance use disorders, the primary purpose of the current study was to test the hypothesis that RA, but not PA, is associated with suicide attempts after controlling for important covariates. We also examined the association of RA and PA with suicidal ideation. We tested interactions of RA and PA with sex, given differences between males and females in the propensity for violence (Corrigan & Watson, 2005) and suicidal behavior (Kessler et al., 1999) together with data suggesting the importance of examining sex differences in the magnitude of the association of measures of aggression and suicidal behavior (Conner et al., 2001).

Methods

Procedure

Brief announcements were made following educational lectures at four residential substance use treatment programs in Western New York. The programs have an 11 to 21-day average length of stay and use an abstinence-based model. Patients who were interested came forward and were scheduled for a 1:1 screening appointment. Participation rates at the sites ranged from 47% to 81%. The study was approved by the Internal Review Boards of the two participating universities and a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health was obtained.

Participants

Six individuals with missing data were excluded, yielding a sample of 878 for the analyses. The mean age of participants was 38.1 (± 10.2) years. There were 622 (70.8%) men and 256 (29.2%) women; 460 (52.4%) participants identified themselves as white non-Hispanic, 341 (38.8%) as Black non-Hispanic, and 77 (8.8%) as another race/ethnicity; 254 (28.9%) reported less than 12 years of education and 624 (71.1%) had 12 years or more.

Measures

Outcomes

A question from the National Comorbidity Survey or NCS (Kessler et al., 1999) assessed lifetime ideation, “Have you ever seriously thought about committing suicide?”, and a slightly modified NCS question assessed lifetime attempt, “Have you ever tried to kill yourself or attempt suicide?” We formed three mutually exclusive groups: history of suicide attempt, with or without suicidal ideation (230, 26.2%), no history of attempts but history of suicidal ideation (179, 20.4%), and a non-suicidal group with no history of ideation or attempts (469, 53.4%). Overwhelmingly, suicide attempters reported a history of ideation consistent with ideation being a necessary but not sufficient condition for an attempt (Kessler et al., 1999).

Assessments of RA and PA

The Impulsive-Premeditated Aggression Scales (IPAS; Stanford et al., 2003) were developed to yield measures of impulsive aggression (akin to RA) and premeditated aggression (akin to PA). Respondents are asked to indicate level of agreement on a 5 point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Each statement asks subjects to reflect on their emotional, cognitive, or behavioral state before, during, and after aggressive acts committed over their lifetime. A complete listing of items is available in Stanford et al. (2003). In the original study of the IPAS, a community sample of 93 men referred for assessment due to a history of anger/aggression problems were administered the 30-item IPAS (Stanford et al., 2003). A principal components analysis (PCA) yielded a PA factor and a RA factor. Preliminary construct validity was established by comparing the separate factors on a number of external variables. RA scores correlated higher than PA scores on self-report measures of irritability and anger control. PA scores, by comparison, correlated more highly with measures of antisocial/impulsive behavior, extraversion, neuroticism, self-harm, and overall aggression—a profile that is consistent with the finding that antisocial and psychopathic individuals are prone to PA (Stanford et al., 2003). Subsequently, the two factors identified in the original study were validated using the IPAS in forensic patients (Kockler, Stanford, Nelson, Meloy, & Stanford, 2006), conduct disordered adolescents (Mathias et al., 2007), and college students (Haden, Scarpa, & Stanford, in press). In these studies, the correlation between the two scales was low, ranging from r=−.02 to .32, demonstrating that the independence of the scales, and the internal consistency of the scales, was acceptable (α ≥.72). Haden et al. (in press) also demonstrated a strong relation between RA and anger as well as negative life events. A psychometric study of the IPAS with methadone maintenance patients (Conner, Houston, Sworts, & Meldrum, 2007b) showed that the scales had a low intercorrelation (r= .02), acceptable internal consistency (α ≥.74), and good test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation ≥ .63), supporting their use with treated substance abusers.

To identify the IPAS items that are most relevant for characterizing aggressive behavior in substance dependent individuals, an exploratory PCA was conducted on the IPAS using the current sample. Consistent with the prior factor analytic studies (Haden et al., in press; Kockler et al., 2006; Stanford et al., 2003), we first conducted an item analysis in which item-total correlations were calculated for each scale and t tests were computed between item scores in the top and bottom quartiles of the respective scale to determine whether items differentiated extreme groups. Four items did not have a significant corrected total item correlation (p<.05) or did not differentiate between extreme groups and were dropped from further analysis. The remaining 26 items were submitted to the PCA. The number of factors to be rotated was determined by the use of tables in Lautenschlager (1989). A varimax rotation with .40 as the minimum loading criterion was used to obtain an orthogonal factor solution. One item (loading <.40) was excluded and three factors were identified. Based on the content of the items, the scales were identified as PA (8 items), RA (13 items), and a third unidentified factor (4 items). This third factor contained no items loading at .60 and above, thus was not considered reliable per the guidelines of Guadagnoli and Velicer (1988). We included only those items loading on the PA and RA scales further.

We next identified “key” items for the RA and PA scales by comparing factor loadings from our sample and the three previous factor analytic studies in adults (Haden et al., in press; Kochler et al., 2006; Stanford et al., 2003). Ten key items for the RA scale and 8 key items for the PA scale, identified as loading on the same scale in at least 3 of 4 samples, were used in the current analysis. Examples of RA items include: “When angry I acted without thinking” and “I feel I lost control of my temper during the acts.” Examples of PA items include: “I think the other person deserved what happened to them during some of the incidents” and “I feel my actions were necessary to get what I wanted.” Internal consistency values for the RA and PA scales were α=.73 and α=.77, respectively. Three extremely low scores (> 3 standard deviations below the mean) were identified on the RA scale and they were changed to one unit below the lowest, non-outlier score to reduce their influence (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

Assessments of covariates

Depressive symptoms. The depression items from the Physicians Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999), with the suicide item omitted, yielded an 8-item scale of current depressive symptoms (α = .84). Alcohol problem severity. Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Bohn, Babor, & Kranzler, 1997) scores provided a continuous assessment of the severity of alcohol-related problems in the past year (α = .83). Primary substance of use. The item “Which drug, including alcohol, is your primary substance of use?” was asked to create three mutually exclusive categories of primary substance: alcohol, cocaine, and other. Supporting the item’s validity, primary substance of use correlated highly with items that ask which substance was used “most frequently (r= .79, p < .001)” and “caused the most problems” (r= .68, p < .001). Breadth of drug use. Using a list of drugs, participants reported their frequency of use of these substances on a 6-point range from “never” to “(nearly) every day.” The number of categories of substances used weekly or more were added to create a continuous measure of the breadth of drug use. Domains assessed by the above covariates have been shown to be associated with suicidal behavior among substance abusers (Conner et al., 2007a; Ilgen, Harris, Moos, & Tiet, 2007).

Measure used in sensitivity analysis

Among the suicide attempt group, their expectation of lethality of the act, an aspect of suicide intent, was assessed with a self-report item created for the study: “Did you expect to live or die before you made the suicide attempt?” with four response options: “100% thought I would live”, “mostly thought I would live”, “mostly thought I would die”, or “100% though I would die.”

Analyses

Analyses were based on unordered multinomial logistic regression models (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000) that compared the attempt and ideation groups to non-suicidal subjects. Odds ratios and asymptotic confidence intervals were computed using the method of profile likelihood (McCullagh & Nelder, 1989). Statistical significance is based on alpha = .05. Goodness-of-fit tests using the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic were derived using independent logistic regression analyses comparing each attempter and ideation group respectively to non-suicidal subjects. Predictors were RA and PA along with covariates that included AUDIT score, primary substance of use (alcohol, reference), breadth of drug use, depressive symptoms, sex (female, reference), age, race (white, reference), and education (≥ 12 years, reference). Correlations among predictors were modest (r ≤.41).

The analysis proceeded in three steps using a purposeful selection method (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000). 1) Each variable was examined using a univariate test. Variables showing p<.20 based on the individual tests were retained and entered simultaneously in a saturated model. 2) Using the log-likelihood ratio test, variables with p>.05 were removed sequentially based on their significance. The effect of removal of each variable was scrutinized by examining the change in the coefficients in order to identify potential confounders. 3) Once the variables for the final model were identified, tests of potential moderating effects of RA and PA with sex were examined.

We performed a sensitivity analysis that eliminated attempt subjects reporting that they “100% thought [they] would live” despite the act (n=57, 28% of attempters) to confirm that the results apply to subjects who more definitively meet the criteria for attempted suicide.

Results

Univariate results

Unadjusted analyses are presented in the left columns of Table 1. Results (odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, p-value) show that RA is associated with greater probability of ideation (1.08, 1.04–1.11, p<.01) and attempt (1.08, 1.05–1.11, p<.01). PA is also associated with greater probability of ideation (1.06, 1.03–1.10, p<.01) and attempt (1.09, 1.06–1.12, p<.01). These results indicate that, prior to adjustment for other variables, a one point increase on the RA scale is associated with an 8% (4–11%) and 8% (5–11%) increased probability of ideation and attempt respectively, and a one point increase on the PA scale is associated with a 6% (3–10%) and 9% (6–12%) greater likelihood of ideation and attempt. Probability of both ideation and attempt are also increased among individuals with greater breadth of drug use and higher AUDIT and PHQ-9 scores. Other significant results indicate that attempt is less likely among men and more likely among individuals of “other race/ethnicity,” individuals with < 12 years of education have a greater probability of attempt, and primary “other drug” users have a greater probability of ideation.

Table 1.

Multinomial Models showing Unadjusted Results, Multivariate Results, and Multivariate Results with the Sex by Proactive Aggression Interaction Term

| Independent Variable | Unadjusted Results | Multivariate Results | Multivariate Results with Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideation OR (95% CI) |

Attempt OR (95% CI) |

Ideation OR (95% CI) |

Attempt OR (95% CI) |

Ideation OR (95% CI) |

Attempt OR (95% CI) |

|

| Male | 1.20 (0.79, 1.80) | 0.48** (0.34, 0.67) | 1.24 (0.81, 1.92) | 0.53** (0.36, 0.76) | 1.31 (0.85, 2.02) | 0.53** (0.22, 1.31) |

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Black, non-Hispanic | .89 (0.62, 1.27) | 1.32 (0.94, 1.84) | 0.87 (0.57, 1.31) | 1.05 (0.70, 1.57) | 0.87 (0.57, 1.31) | 1.04 (0.70, 1.55) |

| Other race/ethnicity | .48 (0.22, 1.06) | 1.75* (1.03, 2.97) | 0.48 (0.21, 1.11) | 1.70 (0.93, 3.11) | 0.49 (0.21, 1.22) | 1.73 (0.95, 3.17) |

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Education < 12 years | 1.00 (0.68, 1.48) | 1.62** (1.15, 2.27) | 1.07 (0.70, 1.65) | 1.40† (0.94, 2.07) | 1.09 (0.71, 1.68) | 1.41† (0.95, 2.10) |

| Education ≥ 12 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary Sub. Cocaine | 1.38 (0.92, 2.08) | 1.26 (0.88, 1.79) | 1.77* (1.11, 2.82) | 1.23 (0.79, 1.89) | 1.77* (1.11, 2.83) | 1.24 (0.81, 1.92) |

| Primary Sub. Other | 1.60* (1.01, 2.52) | .79 (0.50, 1.24) | 2.37** (1.39, 4.03) | 1.06 (0.62, 1.82) | 2.37** (1.39, 4.02) | 1.05 (0.61, 1.80) |

| Primary Sub. Alcohol | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Breadth of Drug Use | 1.24** (1.09, 1.40) | 1.20** (1.08, 1.35) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| AUDIT score | 1.03** (1.01, 1.04) | 1.04** (1.02, 1.05) | 1.03** (1.01, 1.05) | 1.02* (1.01, 1.04) | 1.03** (1.01, 1.05) | 1.02* (1.00, 1.04) |

| PHQ-9 Score | 1.08** (1.05, 1.10) | 1.12** (1.09, 1.14) | 1.06** (1.03, 1.08) | 1.09** (1.07, 1.12) | 1.06** (1.03, 1.08) | 1.09** (1.07, 1.12) |

| Reactive Aggression | 1.08** (1.04, 1.11) | 1.08** (1.05, 1.11) | 1.04* (1.01, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 1.04* (1.01, 1.08) | 1.03† (1.00, 1.06) |

| Proactive Aggression | 1.06** (1.03, 1.10) | 1.09** (1.06, 1.12) | 1.04* (1.00, 1.07) | 1.06** (1.02, 1.10) | 1.12* (1.01, 1.24) | 1.21** (1.09, 1.34) |

| Sex × Proactive Agg. Interaction |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | 0.91** (0.85, 0.97) |

Note.

p<.10.

p<.05.

p<.01.

Individuals with lifetime suicide ideation without attempt (ideation) and those with suicide attempt (attempt) are each compared to non-suicidal participants. Scores on AUDIT, Depression, Reactive Aggression, and Proactive Aggression are mean centered in the analysis. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. PHQ-9 = Physicians Health Questionnaire

Multivariate analyses

These results are shown in the middle columns in Table 1. Age and breadth of drug use were dropped from the multivariate analysis through backward elimination. After adjustment, RA is associated with greater probability of ideation (1.04, 1.01–1.08, p<.05) and the result for attempt is marginally nonsignificant (1.02, 0.99–1.06, p=.17). PA is associated with greater probability of ideation (1.04, 1.00–1.07, p<.05) and attempt (1.06, 1.01–1.10, p<.01). Race/ethnicity and education are no longer significantly associated with attempt. However, primary cocaine and “other drug” users have a greater probability of ideation compared to primary alcohol users.

Multivariate analyses including tests for interactions

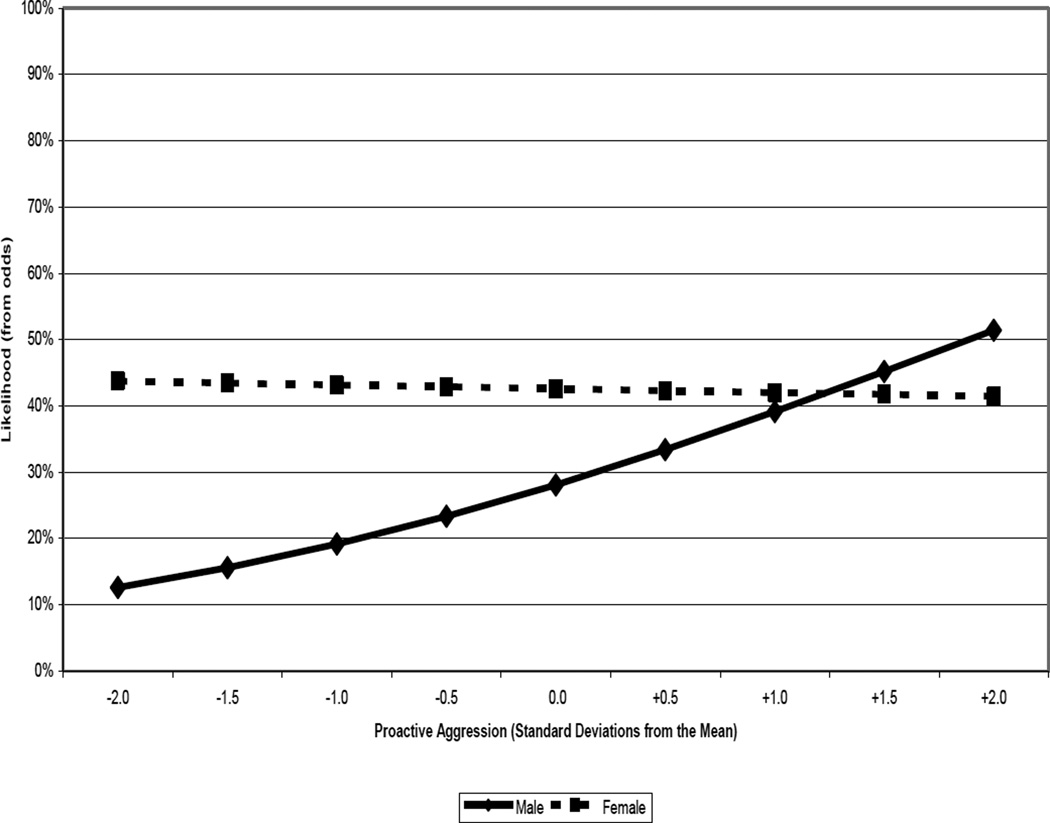

The multivariate analyses were repeated with added examinations of sex by RA and sex by PA interactions. The results showed a statistically significant interaction of sex and PA with attempt (Figure 1). Post hoc analyses (Holmbeck, 2002) indicated that only men showed a higher likelihood of suicide attempt at increased levels of PA (p<.01), while the slope for women was not significant. As shown in the last columns of Table 1, in the model including the interaction term RA shows a statistically significant association with ideation (1.04, 1.01–1.08, p<.05) and a trend-level association with attempt (1.03, 1.00–1.06, p<.10). We also examined scores on the IPAS scales in men and women to rule out that sex differences on the IPAS scales explain the interaction. The data show that this is not a concern as men and women had comparable IPAS scores (mean, SD): RA = 35.3, 6.0 (men) and 36.2, 6.2 (women); PA = 24.2, 5.3 (men) and 23.4, 5.6 (women).

Figure 1.

Predicted likelihood of lifetime history of suicidal attempt(s) versus no history of ideation or attempt for 622 men and 256 women in treatment for alcoholism.

Note. The figure illustrates the sex by PA interaction such that, among men, the likelihood of attempt(s) rises with levels of PA.

Sensitivity analysis

The results (not shown) were comparable to the results of the primary multivariate analysis, including the statistically significant association of sex with PA, suggesting that the results also pertain to suicide attempts when defined more conservatively.

Discussion

Before discussing the findings, it is important to acknowledge the study’s limitations. The data were cross-sectional and so causal inferences cannot be made. Generalizability of results to community populations, other clinical populations, and to individuals showing lower levels of aggression is unclear. Because results pertaining to PA are novel and were not hypothesized, the replicability of present findings is unclear. Further study of the link between PA and suicidal behavior among substance abusers and in other populations is necessary. Although suicidal ideation and attempt are important outcomes in their own right, it is unclear what relevance the data have to death by suicide. Large cohorts will be necessary in order to determine whether suicide death, in addition to ideation and attempt, is linked to RA and PA.

In the present study, RA was associated with attempted suicide in the univariate test and showed nonsignificant but trend level associations in the multivariate models before (p=.17) and after (p<.10) inclusion of the sex by PA interaction term. Given these results, in which other variables appear to have accounted for a portion of the association between RA and suicide attempts, it would be premature to dismiss the role of RA in attempt among individuals with substance dependence. Interestingly, the data support that RA is relevant to ideation among individuals with substance dependence, a question on which there are meager data. Thus, RA may contribute to suicidality broadly, insofar as suicide-related cognitions are more prevalent than suicidal behavior and may be assumed to precede such behavior (Conner et al., 2007a; Kessler et al., 1999).

Results pertaining to PA are novel and were not hypothesized. Results showed statistically significant associations of PA with suicidal ideation and suicide attempt, with the latter result specific to men. PA is associated with psychopathy, a personality disorder characterized by fearlessness, emotional shallowness, and little sentimentality (Woodworth & Porter, 2002). To the extent that these characteristics are present among proactive aggressive males, they may confer greater risk for attempt. Suicidal behavior, particularly a lethal action, engenders fear that must be overcome in order to carry out the behavior (Joiner, 2005). Thus, comparatively greater fearlessness may promote risk among men prone to PA. Relatedly, given decreased emotional depth, these individuals may experience less potentially protective emotional distress prior to suicidal behavior. As well, perhaps males prone to PA experience lower sentimentality concerning suicidal behavior, for example, showing less concern about the impact that suicide may have on family members. Caution is needed because these are post hoc explanations that require further study. Psychopathy and PA are related but not interchangeable constructs, and prior research, though limited, does not support that the interpersonal and affective domain of psychopathy is positively associated with suicide attempts (Verona, Hicks, & Patrick, 2005). Overall, results indicate the need to reconsider the RA-suicidal behavior hypothesis by suggesting that PA may also be important to consider, at least among men. Males are at elevated risk for substance use disorders, suicide deaths, and violence, and indeed PA may be considered a stereotypically male form of aggression. Additional studies are needed to replicate our results and advance a more thorough understanding of the role of proactive aggression in suicidal behavior among substance abusers and other high-risk groups.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by Grants R01 AA016149 and P20 MH071897. We thank Elizabeth Schifano, Katharine Burke, and Kathleen Brundage for data collection/management, and Stephanie Gamble for editing.

References

- Bohn MJ, Babor T, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;56:423–432. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezo J, Paris J, Turecki G. Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completion: a systematic review. Acta Pscyhiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113:180–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Anderson CA. Is it time to pull the plug on hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychological Review. 2001;108:273–279. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Cox C, Duberstein PR, Tian L, Nisbet PA, Conwell Y. Violence, alcohol and completed suicide: A case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001:1701–1705. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Reactive aggression and suicide: Theory and evidence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;8:413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Hesselbrock VM, Meldrum SC, Schuckit MA, Bucholz KK, Gamble SA, Wines JT, Kramer J. Transitions to and correlates of, suicidal ideation, plans, and unplanned and planned suicide attempts among 3729 men and women with alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007a;68:654–662. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Houston RJ, Sworts LM, Meldrum S. Reliability of the impulsive premeditated aggression scale (IPAS) in treated opiate dependent individuals. Addictive Behaviors. 2007b;32:655–659. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey on the frequency of violent behavior in indiviudals with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2005;136:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Muenz LR, Vagge LM, Kelly JF, Bello LR, Michael J. The effect of depression on return to drinking: A prospective study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:259–265. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnoli E, Velicer WF. Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:265–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haden SC, Scarpa A, Stanford MS. Validation of the Impulsive/Premeditated Aggression Scale in college students. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd. New York: Wiley and Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Houston RJ, Stanford MS, Villemarette-Pittman NR, Conklin SM, Helfritz LE. Neurobiological correlates and clinical implications of aggressive subtypes. Journal of Forensic Neuropsychology. 2003;3:67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen MA, Harris AHS, Moos RH, Tiet QQ. Predictors of suicide attempt one year after entry ito substance use disorder treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:635–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–625. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockler TR, Stanford MS, Nelson CE, Meloy JR, Stanford K. Characterizing aggressive behavior in a forensic population. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:80–85. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller G, Preuss UW, Bottlender M, Wenzel K, Soyka M. Impulsivity and aggression as predictors of suicide attempts in alcoholics. European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience. 2002;252:155–160. doi: 10.1007/s00406-002-0362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschlager GJ. A comparison of alternatives to conducting Monte Carlo analyses for determining parallel analyses criteria. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1989;24:365–395. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2403_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P-Y, Tsai G. Association between serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism and suicide: results of a meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nature Reviews.Neuroscience. 2003;4:819–828. doi: 10.1038/nrn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias CW, Stanford MS, Marsh DM, Frick PJ, Moeller FG, Swann AC, Dougherty DM. Characterizing aggressive behavior with the Impulsive/Premeditated Aggression Scales among adolescents with conduct disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2007:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized linear models. London: Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pulay AJ, Dawson DA, Hasin DS, Goldstein RB, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP, Huang B, Chou SP, Grant BF. Violent behavior and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol-Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:12–22. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EAR, Brower KJ, Gomberg ESL. Explaining unexpected gender differences in hostility among persons seeking treatment for substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:667–674. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinka JA, Busch RM, Robichaux-Keene N. A meta-analysis of the association between the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and trait anxiety. Molecular Psychiatry. 2004;9:197–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford MS, Houston RJ, Mathias CW, Villemarette-Pittman NR, Helfritz LE, Conklin SM. Characterizing aggressive behavior. Assessment. 2003;10:183–190. doi: 10.1177/1073191103010002009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4th. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Turecki G. Dissecting the suicide phenotype: the role of impulsive-aggressive behaviours. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2005;30:398–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag HM. Serotonin disturbances and suicide risk: Is aggression or anxiety the interjacent link? Crisis. 2000;21:160–162. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.21.4.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona E, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ. Psychopathy and suicidality in female offenders: mediating influences of personality and abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1065–1073. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Thompson JM, Cherpitel C, Macdonald S, Marais S, Borges G. Gender differences in the relationship between alcohol and violent injury: an analysis of cross-national emergency department data. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:824–833. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodworth M, Porter S. In cold blood: Characteristics of criminal homicides as a function of psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:436–445. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]