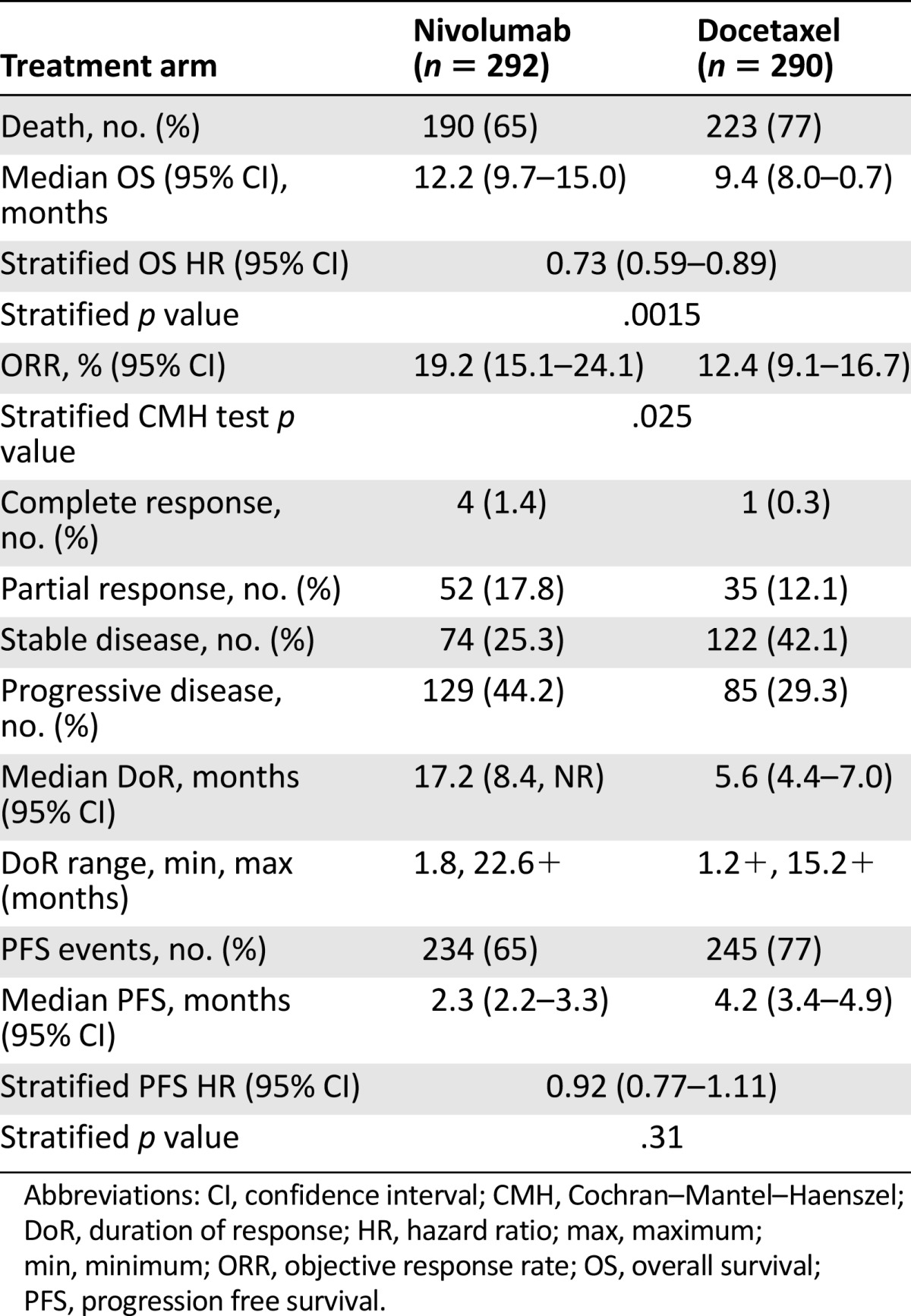

In the CheckMate 057 trial, an international, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial in patients with metastatic nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer with progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy, improved overall survival and objective response rates were demonstrated with nivolumab compared with docetaxel. Progression-free survival did not differ between the two arms of the study.

Keywords: Nivolumab, Non-small cell lung carcinoma, PD-1 inhibitor, Immunotherapy

Abstract

On October 9, 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration expanded the nivolumab metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) indication to include patients with nonsquamous NSCLC after a 3.25-month review timeline. Approval was based on demonstration of an improvement in overall survival (OS) in an international, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial comparing nivolumab to docetaxel in patients with metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC with progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy. The CheckMate 057 trial enrolled 582 patients who were randomized (1:1) to receive nivolumab or docetaxel. Nivolumab demonstrated improved OS compared with docetaxel at the prespecified interim analysis with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.73 (p = .0015), and a median OS of 12.2 months (95% CI: 9.7–15.0 months) in patients treated with nivolumab compared with 9.4 months (95% CI: 8.0–10.7 months) in patients treated with docetaxel. A statistically significant improvement in objective response rate (ORR) was also observed, with an ORR of 19% (95% CI: 15%–24%) in the nivolumab arm and 12% (95% CI: 9%–17%) in the docetaxel arm. The median duration of response was 17 months in the nivolumab arm and 6 months in the docetaxel arm. Progression-free survival was not statistically different between arms. A prespecified retrospective subgroup analysis suggested that patients with programmed cell death ligand 1-negative tumors treated with nivolumab had similar OS to those treated with docetaxel. The toxicity profile of nivolumab was consistent with the known immune-mediated adverse event profile except for 1 case of grade 5 limbic encephalitis, which led to a postmarketing requirement study to better characterize immune-mediated encephalitis.

Implications for Practice:

Based on the results from the CheckMate 057 clinical trial, nivolumab represents a new treatment option for patients requiring second-line treatment for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. The role of nivolumab in patients with sensitizing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) alterations is less clear. Until dedicated studies are performed to better characterize the role and sequence of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) therapy, patients with EGFR or ALK alterations should have progressed on appropriate targeted therapy before initiating PD-1 inhibitor therapy. Some patients whose tumors lack programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression also appear to have durable responses. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted approval to Dako’s PD-L1 test, PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx, which the applicant claimed as a nonessential complementary diagnostic for nivolumab use.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer after prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women. Estimates for lung cancer in the U.S. for 2015 were 221,200 new cases, with 158,040 deaths, and accounting for 27% of all cancer deaths [1]. There are a number of risk factors in the development of lung cancer that have been identified; the leading cause is exposure to cigarette smoke [2]. Lung cancer is broadly divided into two categories: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; about 85% of cases) and small cell lung cancer. NSCLC consists of two major histologic subtypes: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Cytotoxic, platinum doublet-based chemotherapy has been the standard first-line treatment for unselected patients with metastatic NSCLC, with median survivals of 8 to 12 months [3]. In the second-line treatment setting for advanced nonsquamous cell NSCLC (non-SQ NSCLC), docetaxel with or without ramucirumab, pemetrexed (non-SQ only), and erlotinib are U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved regimens [4–7]. However, response rates are low and effects on survival are modest. With the advent of targeted therapeutic approaches, a number of novel agents, such as monoclonal antibodies, antibody directed conjugates, and small molecule kinase inhibitors, have been developed to target specific molecular aberrations [8].

Newer therapeutic modalities have focused on targeting the immune system [9]. Pathways involved in inhibiting antitumor T-cell responses (activation of the inhibitory coreceptors cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 [CTLA-4] and programmed cell death 1 [PD-1] on T cells) are thought to allow tumors to evade the immune system. PD-1 inhibitors, a new class of immune checkpoint inhibitors, are thought to block T-cell inhibitory signal pathways by preventing engagement of PD-1 to its ligands (PD-L1/2). Nivolumab was approved in March 2015 for the treatment of metastatic squamous NSCLC after prior platinum-based chemotherapy, based on the results of the CheckMate 017 (CM017) clinical trial and became the first approved immunotherapy in the treatment of squamous cell lung cancer [10].

CheckMate 017 was a randomized (1:1), open-label study enrolling 272 patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC who had experienced disease progression during or after 1 prior platinum doublet-based chemotherapy regimen regardless of PD-L1 status. Patients were randomly assigned to receive nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks (n = 135) or docetaxel (n = 137) 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks intravenously. The median age of patients was 63 years, the baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 0 (24%) or 1 (76%), and the majority of patients were white (93%) and male (76%). The application went through an expedited review process, given the survival advantage (hazard ratio: 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.44–0.79; p < .001) observed when compared with docetaxel, the primary efficacy outcome. This initial nivolumab approval is described in more detail by Kazandjian et al. [11].

Subsequent to this approval, pembrolizumab received accelerated approval for patients with PD-L1-positive metastatic NSCLC following platinum-containing chemotherapy based on an objective response rate (ORR) of 41% in a prospectively defined subgroup that was retrospectively analyzed for ≥50% PD-L1 expression [12–14]. Nivolumab received an expanded indication to include all NSCLC after prior platinum-based chemotherapy on October 9, 2015, based on the results of clinical trial CheckMate 057 (CM057). This paper describes the FDA’s review of CM057 in support of expanding nivolumab’s indication; further details on the trial are described by Borghaei et al. [15].

Trial Design

CM057 was a randomized, open-label, and international trial in patients with metastatic, non-SQ NSCLC who were previously treated with platinum-doublet chemotherapy. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive nivolumab administered intravenously (i.v.) at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks or chemotherapy with docetaxel at a dose of 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks. Patients must have received one line of platinum-based doublet chemotherapy and have had locally advanced or metastatic non-SQ NSCLC. Patients were allowed to receive therapy as third-line if they had previously received an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor for a known EGFR or ALK genetic alteration. Randomization was stratified by prior maintenance therapy (yes or no) and line of prior therapy (first or second line).

Patients were treated until investigator-determined Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 progression or unacceptable toxicity. Patients treated with nivolumab were allowed to be treated beyond disease progression if they had investigator-assessed clinical benefit and did not have rapid disease progression. The primary efficacy endpoint for CA057 was OS defined as the time between the date of randomization and the date of death. For patients without documentation of death, OS was censored on the last date that the patient was known to be alive. Secondary efficacy endpoints included ORR, duration of response (DoR), progression-free survival (PFS), and patient-reported lung cancer symptoms. Additionally, PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker for OS and ORR was evaluated in prespecified retrospective analyses (percentage of tumor cells demonstrating plasma membrane PD-L1 staining of any intensity in a minimum of 100 evaluable tumor cells using the Dako PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx assay; Agilent Technologies, Glostrup, Denmark, http://www.dako.com).

The trial was designed with a sample size of 574 patients; from this sample, 442 deaths would have to occur to provide 90% probability of demonstrating that nivolumab is superior to docetaxel, assuming a hazard ratio of 0.82 (median OS: 9.8 vs. 8.0 months). The 1 formal interim analysis of OS was to take place when 380 deaths occurred. The analyses of OS and PFS were conducted using a two-sided log-rank test stratified by prior maintenance therapy and line of therapy. Additionally, prespecified retrospective analyses using Kaplan-Meier survival probability for OS for the PD-L1-positive and -negative/indeterminate subgroups (1%, 5%, and 10%) were performed. Analysis of ORR, defined as having a confirmed complete response (CR) or partial response (PR), was performed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test stratified by prior maintenance therapy and line of therapy. Median duration of response was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the corresponding 95% CI.

Results

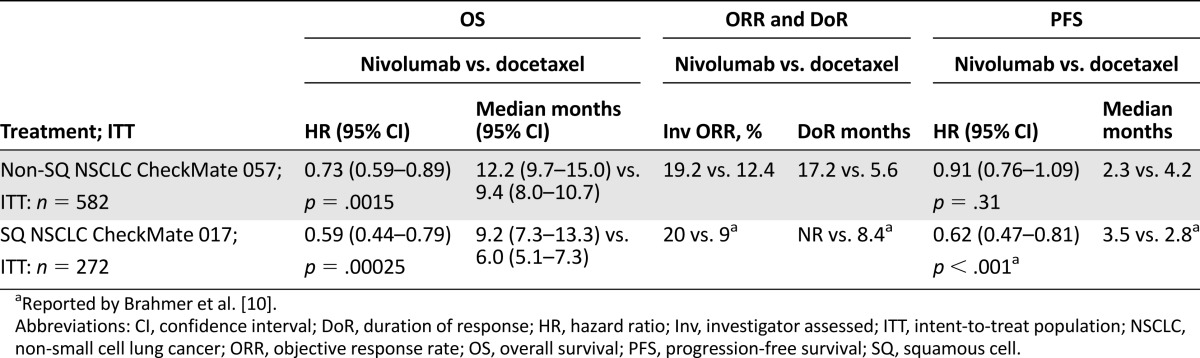

A total of 582 patients (intent-to-treat [ITT] population) were randomly allocated at 106 sites in 22 countries to receive nivolumab (n = 292) or docetaxel (n = 290). Five patients in the nivolumab arm and 22 patients in the docetaxel arm did not receive assigned therapy; therefore, the safety population consisted of 287 patients in the nivolumab arm and 268 in the docetaxel arm. Table 1 summarizes the baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics, which were balanced across the two arms. The median duration of treatment with nivolumab was 2.6 months, compared with 2.3 months for docetaxel.

Table 1.

Study demographics and disease characteristics

Efficacy

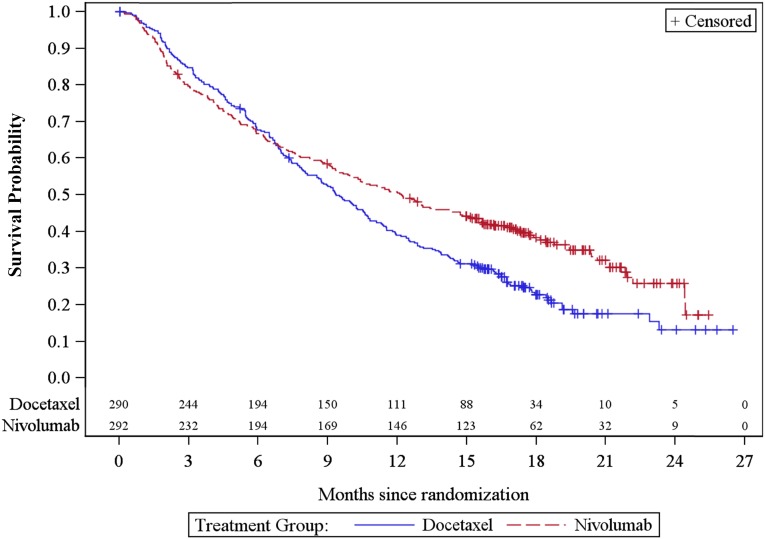

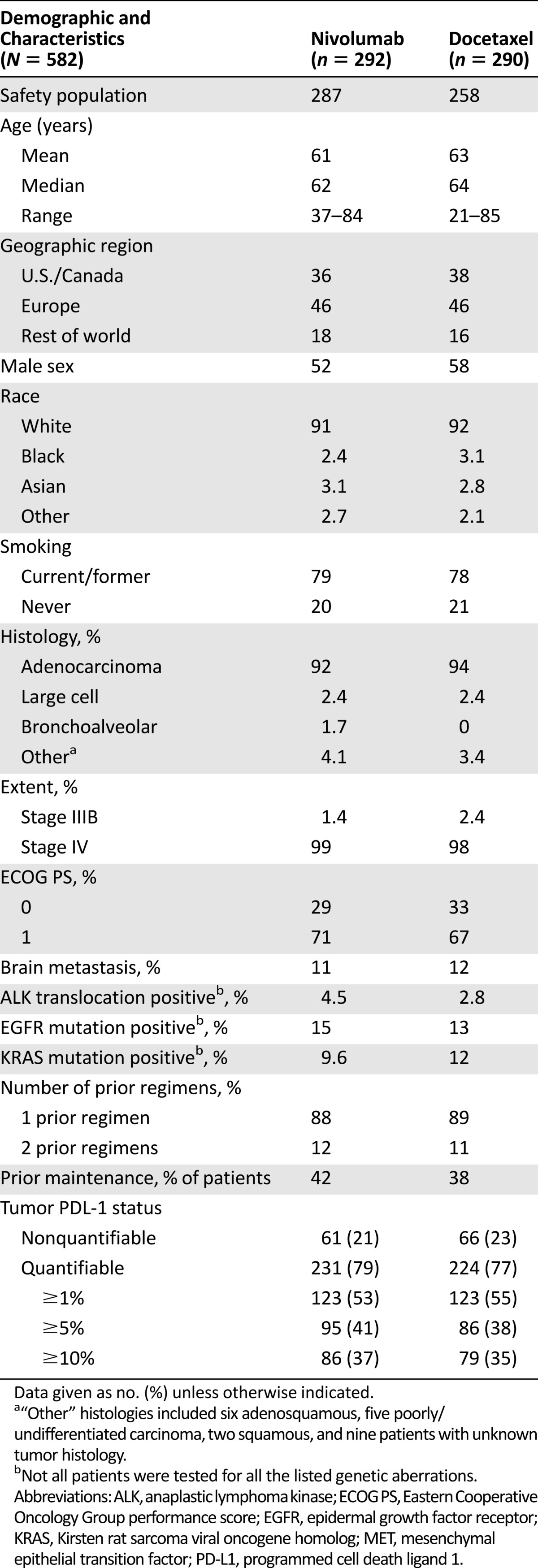

As shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, in the ITT population analysis, there was a statistically significant improvement in OS with an HR of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.60–0.89; p = .0015), and a median OS of 12.2 months (95% CI: 9.7–15.0) for patients randomized to the nivolumab arm, and 9.4 months (95% CI: 8.0–10.7) for patients randomized to the docetaxel arm. The p value of .0015 based on 413 deaths (190 in nivolumab arm and 223 in docetaxel arm) was compared with the allocated significance level of .0408 for this preplanned interim analysis based on 442 deaths. The median patients’ follow-up was 12 months in the nivolumab arm and 9 months in the docetaxel arm.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves in months for overall survival in the intention-to-treat population. Note that the two lines above each x-axis reflect the number of patients at risk.

Table 2.

Key efficacy results for CM057

All analyses for secondary endpoints were considered as the final analyses. In the ITT population, the ORR was 19.2% (95% CI: 15.1%–24.1%) for nivolumab and 12.4% for docetaxel (95% CI: 9.1%–16.7%) (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in PFS between arms (HR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.77–1.11; p = .31). The median PFS was 2.3 months (95% CI: 2.2–3.3) and 4.2 months (95% CI: 3.4–4.9) in the nivolumab and docetaxel arms, respectively.

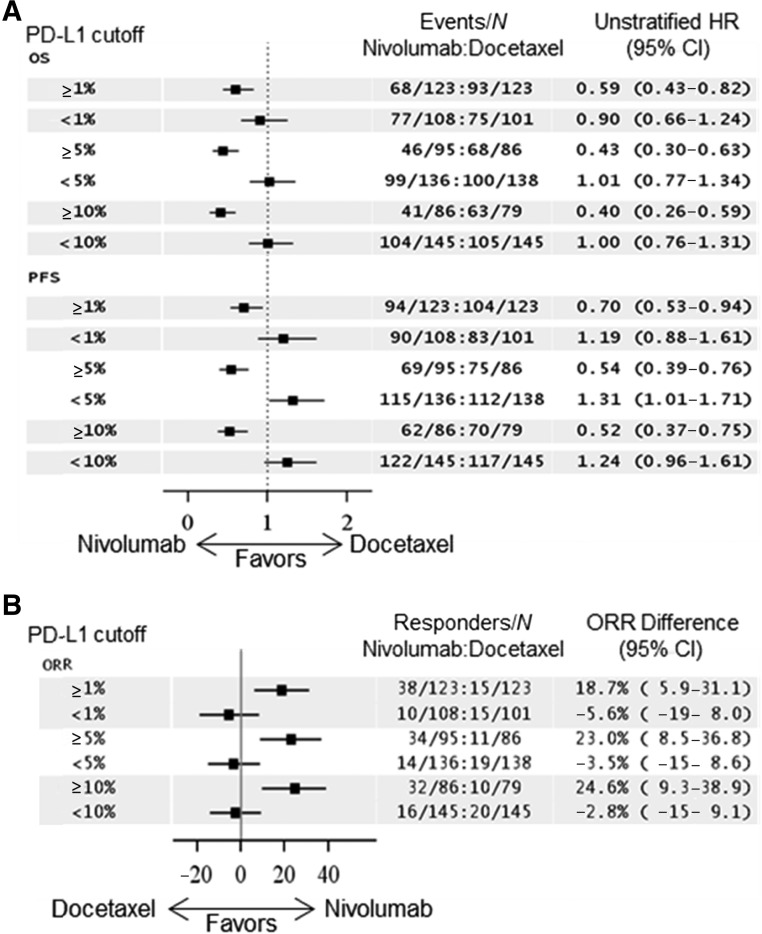

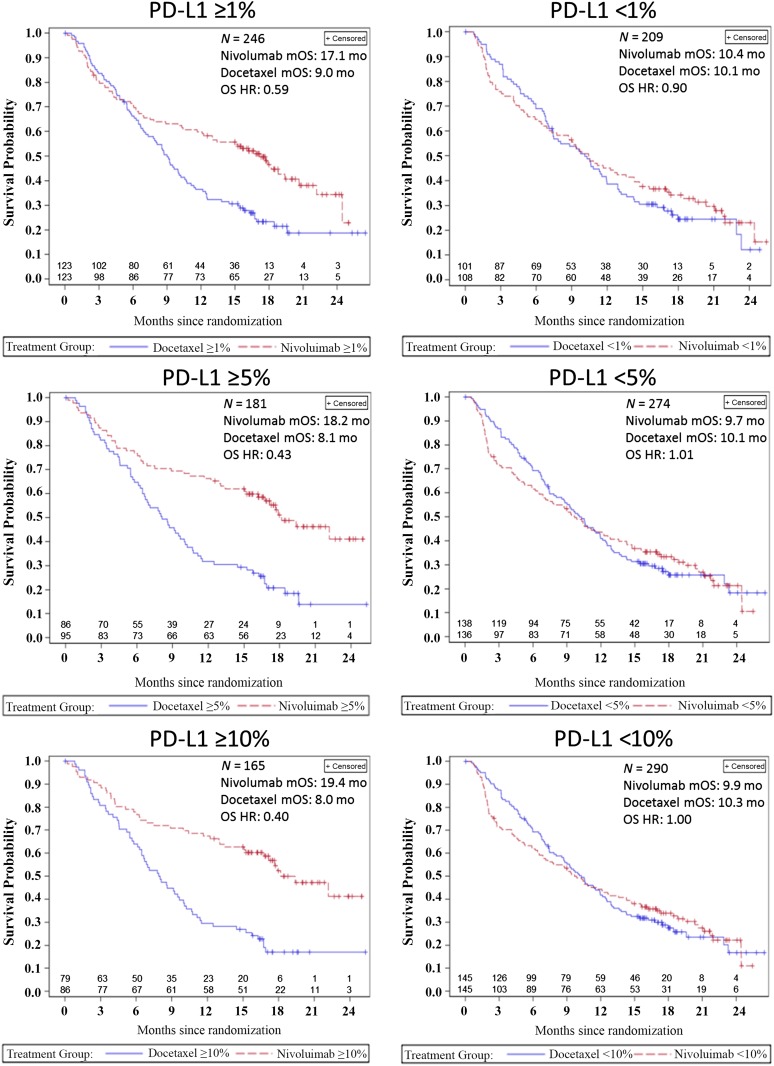

PD-L1 expression status based on archival tumor specimens at baseline was assessed in 455 of the 582 patients, using the DAKO 28-8 pharmDx immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay. The prespecified subgroups and their respective OS HR benefit using different cut points are shown in Figure 2A and ORR differences are shown in Figure 2B. A retrospective, prespecified analysis of survival using Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival probability curves based on the PD-L1 cut point subgroups is shown in Figure 3. The PD-L1-negative subgroups’ KM curves appear similar to that of the ITT population, with the crossing of the curves in favor of nivolumab at about the 9- to 12-month point. However, in the PD-L1-positive subgroups, the KM curves appear to cross earlier, at about the 3- to 6-month time point.

Figure 2.

Prespecified forest plots of OS and PFS HRs and ORR differences based on PD-L1 expression levels. PD-L1 cut points of 1%, 5%, and 10% were used for the analysis. HRs and ORRs toward the left of the arrows favor nivolumab. (A): An HR of 1 suggests no difference between arms and less than 1 favors nivolumab, whereas an HR greater than 1 favors docetaxel. (B): Responders were defined as patients who acquired a complete or partial confirmed response as their best response per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1. An ORR difference of 0 suggests no difference between arms and less than 0 favors docetaxel, whereas greater than 0 favors nivolumab.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; N, numbers of patients greater than or less than the given cutoff used; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1.

Figure 3.

Prespecified retrospective analysis of overall survival represented by Kaplan-Meier survival curves in months based on the PD-L1 cut-points of 1%, 5%, and 10%. Note that the two lines above each x-axis reflect the number of patients at risk.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; mo, month; mOS, median overall survival; OS, overall survival; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1.

In an additional exploratory subgroup analysis, patients with EGFR mutation-positive tumors had an OS HR of 1.18 (95% CI: 0.69–2.00), favoring docetaxel. Approximately one-half of the 71 patients with strictly EGFR-positive tumors and one-third of the 10 patients with strictly ALK-positive tumors (no other determined concomitant driver mutation) received appropriate tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy before nivolumab.

Toxicity

Of the 582 patients randomized in the CM057 study, 555 (nivolumab: n = 287; docetaxel: n = 268) received at least 1 dose of protocol-specified therapy and were included in the safety analysis. The most common adverse events occurring in at least 10% of patients treated with nivolumab and at a higher incidence than docetaxel (by at least 2% for grade 3–4 events or by at least 5% for all-grade events) were as follows: cough (all grades: 30% vs. 25% for nivolumab vs. docetaxel, respectively; grades 3–4: 0.3% vs. 0%), decreased appetite (all grades: 29% vs. 22%, grades 3–4: 1.7% vs. 1.5%), constipation (all grades: 23 vs. 17%; grades 3–4: 0.7% vs. 0.7%), and pruritis (all grades: 11% vs. 1.9%; grades 3–4: 0%). Other frequent, clinically important adverse events that occurred at similar incidences with docetaxel included fatigue (all grades: 49% vs. 58%; grades 3–4: 6% vs. 10%) and musculoskeletal pain (all grades: 36% vs. 36%; grades 3–4: 4.2% vs. 3.4%).

The laboratory abnormalities worsening from baseline in at least 10% of patients treated with nivolumab and at a higher incidence than docetaxel included hyponatremia (all grades 35% vs. 32%; grades 3–4: 6% vs. 2.7%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST; all grades: 28% vs. 14%; grades 3–4: 2.8% vs. 0.4%), increased alkaline phosphatase (all grades: 27% vs. 18%; grades 3–4: 1.1% vs. 0.4%), increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT; all grades: 23% vs. 15%; grades 3–4: 2.4% vs. 0.4%), increased creatinine (all grades: 18% vs. 13%; grades 3–4: 0% vs. 0.4%), and increased thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH; all grades: 17% vs. 5%).

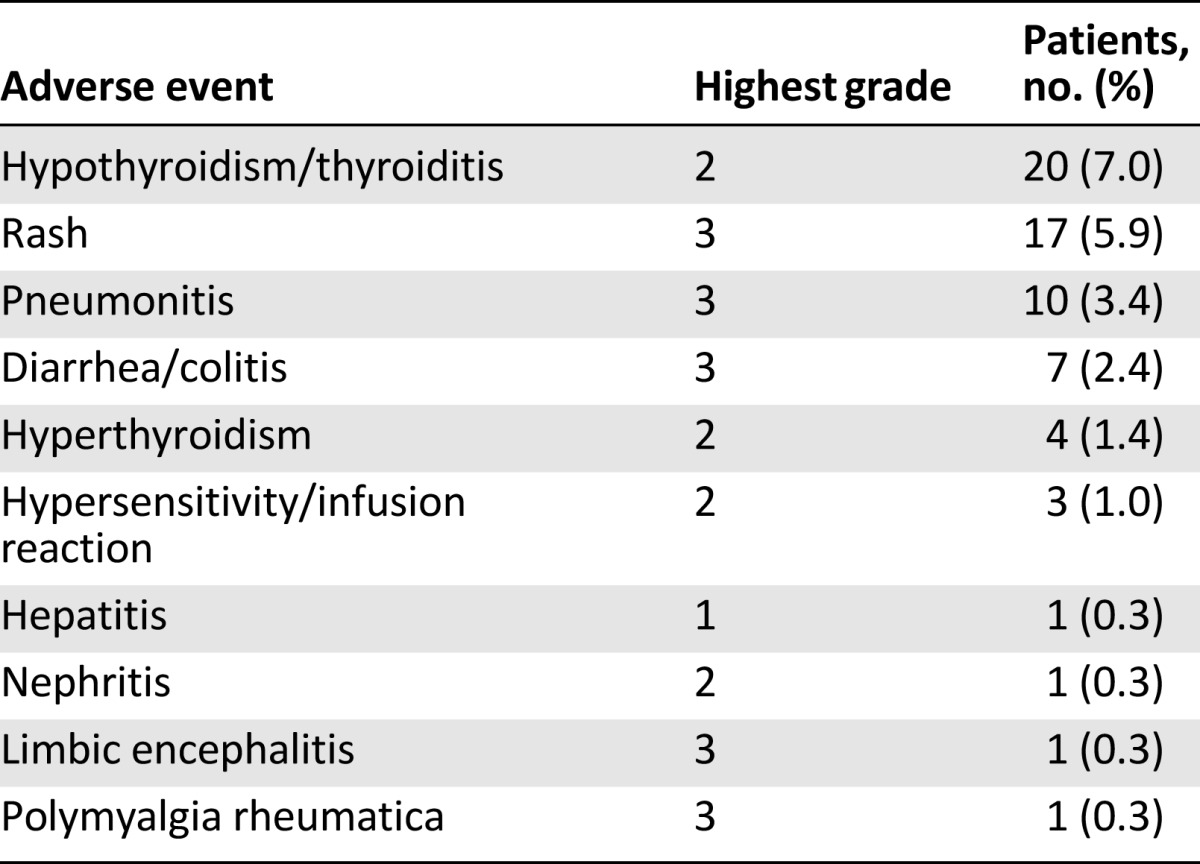

Immune-mediated adverse events, defined as events requiring the use of systemic steroids, endocrine events, or events for which an alternative etiology was unlikely, are summarized in Table 3. Immune-mediated adverse reactions were generally managed with administration of high-dose (2–4 mg/kg prednisolone equivalent) corticosteroids followed by a tapered dose and interruption of nivolumab therapy. The pattern of immune-mediated adverse events was generally consistent with the known toxicity profile of nivolumab, with the exception of a case of grade 5 immune-mediated limbic encephalitis in a 70-year-old woman following her 14th infusion. Autopsy revealed a dense lymphocytic infiltrate of the bilateral thalami. The FDA has mandated a postmarketing requirement for enhanced pharmacovigilance for immune-mediated encephalitis to better characterize the incidence, severity, outcomes, and associated clinical and laboratory findings.

Table 3.

Nivolumab immune-mediated toxicities

Discussion

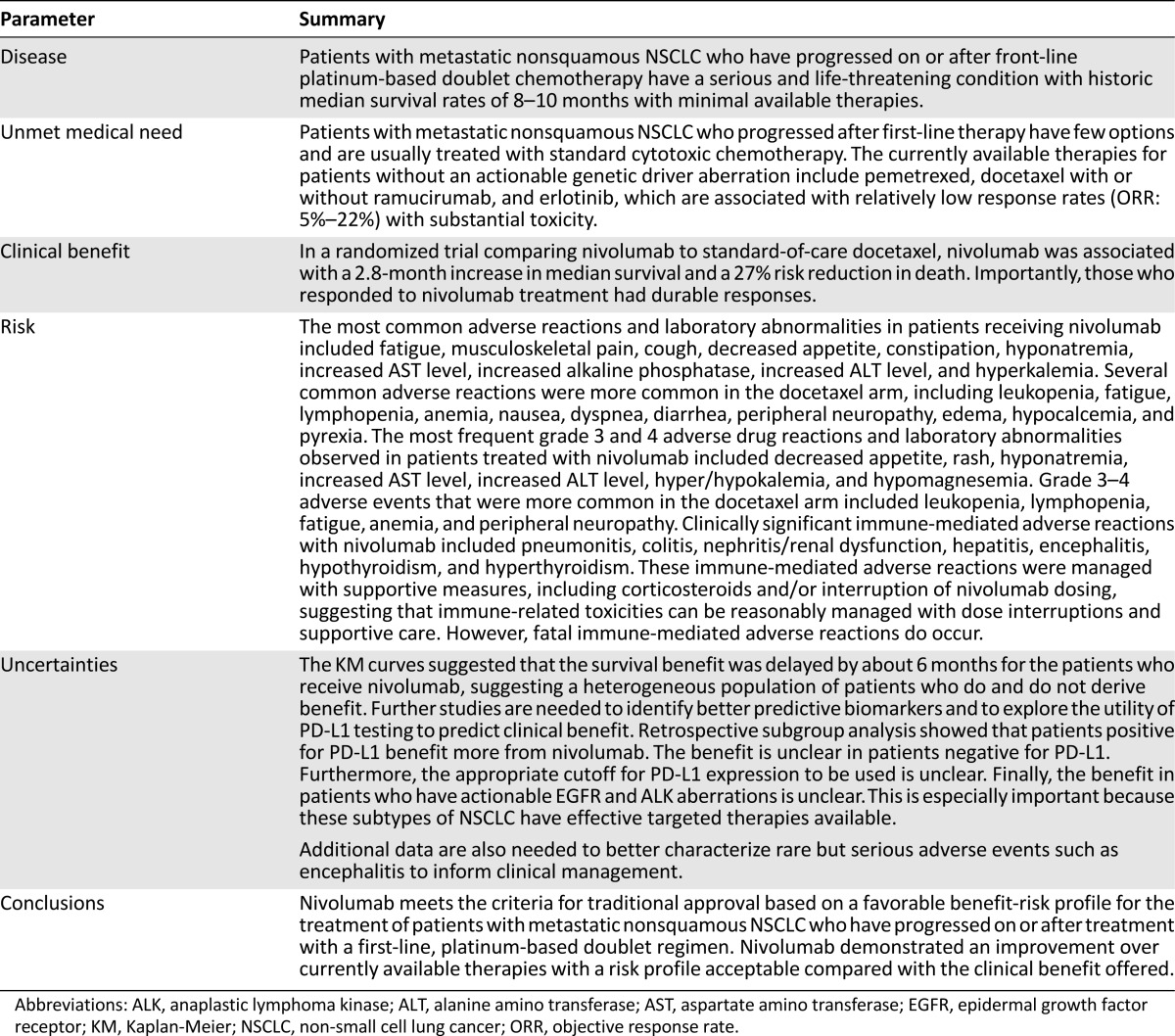

On October 9, 2015, the FDA granted regular approval to nivolumab based on a favorable benefit-risk assessment for the treatment of patients with metastatic NSCLC with progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients with EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations should have disease progression on FDA-approved therapy for these aberrations before receiving nivolumab. Table 4 summarizes the FDA benefit-risk analysis.

Table 4.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration benefit-to-risk summary

Study CM057 met its prespecified interim OS analysis of demonstrating superiority of nivolumab over docetaxel in this disease setting. A statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in survival was observed, with a median OS improvement of 2.8 months compared with docetaxel, and a relative risk decrease of 27% (HR: 0.73; p = .0015). Of note, there appeared to be a delayed benefit for nivolumab, as seen by the KM curves in which the population of patients allocated to nivolumab appeared to have more deaths before the 6-month time point. The most likely explanation for this observation is that the population enrolled was heterogeneous, and not selected based on PD-L1 status. When looking only at PD-L1-positive patients, the KM OS curves separate early. The OS results were supported by a modest but statistically significant difference in ORR (19% vs. 12%; p = .025) and a notable difference in duration of response (17 months vs. 6 months).

PFS was not found to be statistically significantly different, with a HR of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.77–1.11; p = .39). Interestingly, the KM PFS curves [15] appear similar to the OS curves in which, early on, treatment with docetaxel appears more beneficial until a time point between 3 and 6 months, when there is an inflection of the curve favoring nivolumab. This finding might be due to the heterogeneity of the patient population including PD-L1 expression, EGFR/ALK status, and other undetermined factors. Median PFS may not be an optimal endpoint to define clinical benefit with immunotherapies, and new endpoints will be needed for this emerging field.

The toxicity profile of nivolumab was generally consistent with that seen in earlier studies and compared favorably with that of docetaxel. Pneumonitis was the most common, potentially life-threatening, immune-mediated adverse event. No deaths were attributed to pneumonitis, in contrast with reports of several prior studies of nivolumab in NSCLC [16–18], likely reflecting the impact of a learning curve by investigators, including more aggressive management with drug discontinuation and early administration of corticosteroids. Increases in liver enzyme levels were common and one case of immune-mediated hepatitis was noted. One patient died of immune-mediated limbic encephalitis, which has not been previously associated with nivolumab. Thus, immune-mediated encephalitis was added to the “Warnings and Precautions” section 5 of the U.S. product insert and a postmarketing requirement study was mandated to better characterize immune-mediated encephalitis.

Of note, retrospective subgroup analysis suggested that patients with PDL-1 expression levels of ≥1% had an OS HR of 0.59, favoring nivolumab over docetaxel, whereas patents with expression levels of < 1% had an OS HR of 0.90. Patients with PD-L1 expression of ≥5% had an OS HR of 0.43, favoring nivolumab over docetaxel, whereas patients with an expression level of <5% had an OS HR of 1.01. The KM curves for OS in these retrospective subgroups, shown in Figure 3, show that the curves split apart earlier in favor of nivolumab in patients with PD-L1-positive tumors, especially at the ≥5% and ≥10% cutoff as compared with the ITT or PD-L1-negative populations.

When interpreting these data, it appears clear that regardless of which cut point is used, patients with PD-L1-positive tumors appear to have longer survival when treated with nivolumab compared with docetaxel. Interestingly, the KM survival curves for the PD-L1-positive subgroups do not suggest a delayed treatment effect over docetaxel and appear more similar to the previous squamous NSCLC CM017 trial results.

Despite no apparent superiority in OS between nivolumab and docetaxel in PD-L1-negative patients, the FDA granted the approval to the entire ITT population for the following reasons: (a) the findings were considered exploratory because ascertainment of PD-L1 was not 100% and PD-L1 was not a stratification factor at randomization, (b) PD-L1-negative patients were not harmed by nivolumab as compared with the active control and some PD-L1 patients did benefit as evidenced by the roughly 10% ORR with sustained DoR, and (c) nivolumab has a different and more favorable adverse event profile compared with docetaxel. The FDA also granted approval to Dako’s PD-L1 test, PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx, which the applicant termed a “complementary diagnostic” to guide physicians in decision making. Although there is no formal regulatory definition of a complementary diagnostic, it may be distinguished from a companion diagnostic as a test that is not essential but provides information to prescribers in aiding management of treatment expectations and evaluating the potential benefit and risk to the patient.

Another important consideration is for patients with tumors that contain targetable driver mutations. There are currently several approved agents targeting EGFR and ALK aberrations, and agents targeting other driver oncogenes in NSCLC are in development. Thus, the sequencing of targeted therapies with immunotherapies will be a critical area of clinical investigation. Based on the data from the CM017 study, PD-L1 status does not appear to be a predictive biomarker for patients with squamous NSCLC [10], which may be because of the close association of this tumor type with smoking, a carcinogenic pathway that produces high genetic heterogeneity and a high T-cell inflammatory response [19].

In contrast, many targetable driver aberrations in adenocarcinomas, such as EGFR mutations, are not associated with smoking. These tumors are less likely to have vast DNA heterogeneity and, thus, less neoantigen presentation. In addition to PD-L1 expression, other biomarkers, such as mutational load, may be important in predicting response to PD-1 axis blockade [5]. The mutational landscape may also be a predictive biomarker for CTLA-4 blockade therapy in melanoma, where a specific neoantigen landscape was found to be a predictor of response to CTLA-4 blockade [20].

In the CM057 study, exploratory subgroup analysis suggested that patients positive for EGFR mutation may derive less benefit with nivolumab. Given this finding, and the fact that efficacious EGFR and ALK inhibitors are available, the FDA and the applicant recommended that a limitation of use be incorporated in the “Indications and Usage” section of product labeling to state that patients with EGFR and ALK aberrations should progress on approved targeted therapy before receiving nivolumab. Future studies should address optimal combination and sequencing strategies of immunotherapies and targeted therapies.

Conclusion

Similar to CheckMate 017 in squamous NSCLC, the improved survival in patients with relapsed NSCLC treated with nivolumab compared with docetaxel in CheckMate 057 establishes a new treatment option for patients who have progressed on platinum-doublet chemotherapy. Both CheckMate 017 (in squamous cell NSCLC) and 057 (in nonsquamous cell NSCLC) met their primary endpoints of demonstrating improved overall survival compared with docetaxel. These two key studies and their efficacy outcomes supporting the current nivolumab label for the treatment of patients with metastatic NSCLC are shown in Table 5. This led to the FDA’s expedited 3.25-month review and approval of CM057 supplemental Biologics Licensing Application. Ongoing studies are investigating nivolumab in the adjuvant and front-line metastatic settings. The combination immunotherapy trials that are under way are of high area interest, particularly to patients with PD-L1-“negative” tumors. Precompetitive collaborations across pharmaceutical companies and diagnostic developers are needed to better describe PD-L1 assays across development programs [21].

Table 5.

Summary of key evidence for the use of nivolumab in patients with metastatic NSCLC with progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: See the related commentary, “Into the Clinic With Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab,” by Catherine A. Shu and Naiyer A. Rizvi, on page 527 of this issue.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Dickran Kazandjian, Daniel L. Suzman, Gideon Blumenthal, Sirisha Mushti, Meredith Libeg, Patricia Keegan, Richard Pazdur

Collection and/or assembly of data: Dickran Kazandjian, Daniel L. Suzman, Gideon Blumenthal, Sirisha Mushti, Kun He, Meredith Libeg

Data analysis and interpretation: Dickran Kazandjian, Daniel L. Suzman, Gideon Blumenthal, Sirisha Mushti, Kun He, Patricia Keegan, Richard Pazdur

Manuscript writing: Dickran Kazandjian, Daniel L. Suzman, Gideon Blumenthal, Kun He, Patricia Keegan, Richard Pazdur

Final approval of manuscript: Dickran Kazandjian, Daniel L. Suzman, Gideon Blumenthal, Patricia Keegan, Richard Pazdur

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: Lung and bronchus cancer. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed October 15, 2015.

- 2.Herbst RS, Gandara DR, Hirsch FR, et al. Lung master protocol (Lung-MAP)-a biomarker-driven protocol for accelerating development of therapies for squamous cell lung cancer: SWOG S1400. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1514–1524. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiller JH, Gandara DR, Goss GD, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer: Then and now. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:981–983. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.5772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oxnard GR, Binder A, Jänne PA. New targetable oncogenes in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1097–1104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.9829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies M. New modalities of cancer treatment for NSCLC: Focus on immunotherapy. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:63–75. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S57550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kazandjian D, Khozin S, Blumenthal G, et al. Benefit-risk summary of nivolumab for patients with metastatic squamous cell lung cancer after platinum-based chemotherapy: A report from the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:118–122. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Keytruda [package insert]. 2015. Available at http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=9333c79b-d487-4538-a9f0-71b91a02b287. Accessed October 27, 2015.

- 14.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim D-W, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brahmer JR, Horn L, Antonia SJ, et al. Survival and long-term follow-up of the phase I trial of nivolumab (Anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538) in patients (pts) with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2013 31(suppl):8030a. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Topalian SL, Sznol M, Brahmer JR, et al. Nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538) in patients with advanced solid tumors: Survival and long-term safety in a phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013 31(suppl):3002a. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Association for Cancer Research. Complexities in personalized medicine: Harmonizing companion diagnostics across a class of targeted therapies. 2015. Available at http://www.aacr.org/ADVOCACYPOLICY/GOVERNMENTAFFAIRS/PAGES/COMPLEXITIES-IN-PERSONALIZED-MEDICINE.ASPX. Accessed December 3, 2015.