Abstract

Monocyte migration requires the dynamic redistribution of integrins through a regulated endo-exocytosis cycle, but the complex molecular mechanisms underlying this process have not been fully elucidated. Glia maturation factor-γ (GMFG), a novel regulator of the Arp2/3 complex, has been shown to regulate directional migration of neutrophils and T-lymphocytes. In this study, we explored the important role of GMFG in monocyte chemotaxis, adhesion, and β1-integrin turnover. We found that knockdown of GMFG in monocytes resulted in impaired chemotactic migration toward formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) and stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF-1α) as well as decreased α5β1-integrin-mediated chemoattractant-stimulated adhesion. These GMFG knockdown impaired effects could be reversed by cotransfection of GFP-tagged full-length GMFG. GMFG knockdown cells reduced the cell surface and total protein levels of α5β1-integrin and increased its degradation. Importantly, we demonstrate that GMFG mediates the ubiquitination of β1-integrin through knockdown or overexpression of GMFG. Moreover, GMFG knockdown retarded the efficient recycling of β1-integrin back to the plasma membrane following normal endocytosis of α5β1-integrin, suggesting that the involvement of GMFG in maintaining α5β1-integrin stability may occur in part by preventing ubiquitin-mediated degradation and promoting β1-integrin recycling. Furthermore, we observed that GMFG interacted with syntaxin 4 (STX4) and syntaxin-binding protein 4 (STXBP4); however, only knockdown of STXBP4, but not STX4, reduced monocyte migration and decreased β1-integrin cell surface expression. Knockdown of STXBP4 also substantially inhibited β1-integrin recycling in human monocytes. These results indicate that the effects of GMFG on monocyte migration and adhesion probably occur through preventing ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation of α5β1-integrin and facilitating effective β1-integrin recycling back to the plasma membrane.

Keywords: adhesion, Arp2/3 complex, cell migration, endocytosis, integrin, ubiquitylation (ubiquitination), glia maturation factor-gamma (GMFG)

Introduction

The migration of monocytes from the circulation toward the surrounding extravascular space is a crucial event in physiological and pathological immune and inflammatory responses. The extravasation of monocytes is a highly orchestrated multistep adhesion cascade that is mediated by dynamic regulation of adhesion molecules expressed on both monocytes and endothelial cells, including integrins (1, 2). Integrins are a large family of heterodimeric transmembrane proteins consisting of an α- and β-subunit that bind extracellular matrix components to provide sites of adhesion and signals for the dynamic rearrangement of cytoskeletal elements in various stages of cell migration (3, 4). Monocytes, like other leukocytes, express distinct integrins, but those most relevant to monocyte migration belong to the β1- and β2-integrin subfamilies. Although the important role of β1/β2-integrins in regulating monocyte transmigration across the endothelium to sites of inflammation has been relatively well studied (5–7), the molecular mechanisms underpinning the dynamic regulation of endo-exocytic trafficking of these integrins are only beginning to emerge.

Accumulating evidence indicates that integrin endocytic trafficking plays an important regulatory role in cell migration and disease progression by affecting integrin function and cell surface distribution as well as the turnover of extracellular matrix molecules (8–10). The trafficking of newly synthesized or recycled integrin molecules to the plasma membrane requires the tight regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, actin-modulating proteins, and vesicular trafficking machineries that selectively sort cargo proteins via various adaptor proteins (11). The final step for integrin trafficking to the cell surface is mediated by the fusion of integrin-containing transport vesicles with the plasma membrane, a process that is poorly understood at the molecular level (12).

A growing number of studies have demonstrated that the interaction of SNARE proteins on vesicles (v-SNAREs) and on target membranes (t-SNAREs) drives intracellular vesicle fusion (13–16). Several SNARE proteins have been implicated in integrin trafficking. For example, the interaction of t-SNARE protein STX6 (syntaxin 6) with the v-SNARE VAMP3 (vesicle-associated membrane protein 3) appears to play a role in cell migration by mediating recycling of heterodimers containing β1-integrin in endothelial cells and HeLa cells (17, 18). In macrophages, the plasma membrane t-SNARE proteins STX4 and SNAP23 (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein 23) interact with VAMP3 to mediate endocytic recycling of α5β1-integrin (19). STX3 and STX4 mediate cell migration by regulation of α5β1- and α3β1-integrin trafficking to the cell surface in HeLa cells (12). In addition, STX4 and STXBP4 (syntaxin-binding protein 4) are specifically critical in the vesicular transport of GLUT4-containing vesicles to the plasma membrane in skeletal muscle, adipocytes, and cardiomyocytes (20–22). These findings indicate that t-SNARE proteins play an important role in cell migration by mediating β1-integrin trafficking.

Glia maturation factor-γ (GMFG),2 a newly recognized actin depolymerization factor/cofilin superfamily protein, is a highly conserved protein throughout eukaryotes from yeast to mammals. GMFG is predominantly expressed in inflammatory cells and microendothelial cells (23, 24). We and others have recently shown that GMFG mediates neutrophil and T-lymphocyte migration via regulation of actin cytoskeletal reorganization (25, 26). Functional studies of GMFG in systems ranging from yeast to mammalian cells have shown that GMFG promotes debranching of actin filaments and inhibits new actin assembly through binding of the Arp2/3 (actin-related protein-2/3) complex (27–29). The Arp2/3 complex plays a fundamental role in both cell migration and intracellular trafficking by mediating membrane remodeling through the endocytic internalization and recycling, degradation, and exocytic transport of membrane components (30, 31). Despite these advances, it remains unclear whether GMFG mediates monocyte migration through modulation of intracellular trafficking of β1-integrin.

Here, we show that GMFG is important for maintaining the stability of β1-integrin protein and the efficient recycling of β1-integrin in monocytes and is required for efficient monocyte chemotaxis, probably through association with STXBP4. These results further support the important role of GMFG in monocyte migration.

Experimental Procedures

Cells and Cell Cultures

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from buffy coats of healthy adult donors by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation according to a protocol approved by the institutional review board of NHLBI, National Institutes of Health, and consistent with federal regulations. Monocytes were purified using a negative selection human monocyte enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Monocytes (2 × 106/ml) were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% human AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich). The human monocytic cell line THP-1 and HEK-293T cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in RPMI 1640 or DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS.

RNA Interference and Transfection

Monocytes (1 × 106 cells) or THP-1 cells (2 × 106 cells) were transiently transfected with a GMFG siRNA, STX4 siRNA, STXBP4 siRNA, control negative siRNA, GFP vector, and/or GMFG-GFP vector using the Nucleofector Kit V and Nucleofector I Program U-01 (Lonza), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The GMFG siRNA (Silencer Select siRNA s18302), STXBP4 siRNA (Silencer Select siRNA s48386), STX4 siRNA (Silencer Select siRNA s13595), and control negative siRNA (Neg-siRNA-2) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. GFP vector and GMFG-GFP plasmid (human cDNA clone, ORF with C-terminal GFP tag) were obtained from ORIGENE. Functional experiments with siRNA-transfected cells were performed 48 h after transfection, when GMFG, STX4, or STXBP4 expression levels were reduced 75% in relevant siRNA-transfected cells compared with control negative siRNA-transfected cells. For GMFG rescue experiments, cells were first transiently transfected with a control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA for 48 h, followed by cotransfection of GFP vector or GMFG-GFP expression plasmid and continuously cultured in complete growth medium for 24 h prior to use.

Monocyte Chemotaxis Assays

Primary human monocytes (5 × 104 cells) or THP-1 cells (5 × 104 cells) in 0.5% BSA-RPMI medium were placed in the upper chamber of a Transwell culture insert (5-μm pore size; Corning Inc.) coated with or without 10 μg/ml fibronectin (FN) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h. Formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) (1–100 nm; Sigma-Aldrich) or SDF-1α (stromal cell-derived factor 1α) (1–100 ng/ml; R&D Systems) was added to the lower well, and the cells were allowed to migrate for 3 h at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Migrated cells in the lower wells were quantified by placing 10-μl aliquots of the medium from the lower wells on a hemacytometer and counting four fields in duplicate.

EZ-TAXIScan Chemotaxis Assays

The EZ-TAXIScan chamber (Effector Cell Institute, Tokyo, Japan) was assembled as described by the manufacturer. Coverslips and chips used in the chamber were coated with 1 μg/ml FN or 1% BSA at room temperature for 1 h, and then monocytes or THP-1 cells were added to the chamber and allowed to migrate. Cell migration toward fMLP (100 nm) or SDF-1α (100 ng/ml) was recorded every 15 s for 30 min at 37 °C in a humidified environmental chamber. Cell migration analysis was conducted using MATLAB software as described previously (32). Cell tracks were subsequently used to compute chemotactic index (directionality) and mean migration speed for each tracked cell at each time point in each experiment. Each image shows a representative section of the final frame in the experiment plus the locations of all cells identified and tracked in the section in all frames.

Adhesion Assays

Ninety-six-well flat bottom plates (BD Biosciences) were coated with 10 μg/ml FN for 1 h. Wells were washed and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h. Monocytes or THP-1 cells (50 μl; 1 × 106 cells/ml) were seeded onto precoated plates and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Cells were then stimulated with fMLP (100 nm) or SDF-1α (100 ng/ml) at 37 °C for 15 min, and unattached cells were subsequently removed by gentle washing with washing buffer (0.1% BSA/PBS) twice. Attached cells were then fixed and stained with crystal violet. The bound crystal violet was dissolved with 1% SDS and analyzed at 590 nm. Values were calculated as -fold increase over levels in unstimulated cells treated with control negative siRNA.

Coimmunoprecipitation Assays

For endogenous coimmunoprecipitation analysis, human THP-1 cells were lysed in IP lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific) and immunoprecipitated overnight with monoclonal GMFG antibody (LifeSpan BioSciences), monoclonal STXBP4 antibody (Thermo Scientific), or monoclonal STX4 antibody (BD Biosciences) and then subjected to Western blotting. For immunoprecipitation analysis using transient transfection, HEK-293T cells were transiently cotransfected with FLAG-tagged GMFG and GFP-tagged STXBP4, with FLAG-tagged GMFG and Myc-tagged STX4 (ORIGENE), or with expression vectors for all three proteins together (Myc-tagged STX4, GFP-tagged STXBP4, and FLAG-tagged GMFG). Forty-eight h after transfection, cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated overnight with anti-FLAG, anti-GFP, or anti-Myc antibodies (ORIGENE). Dynabeads protein G (Life Technologies) was added and incubated for 3 h at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitated complexes-beads were washed three times in the washing buffer, and the proteins were eluted with 2× sample buffer (46.7 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 5% glycerol, 1.67% SDS, 1.55% dithiothreitol, and 0.003% bromphenol blue). Proteins were then subjected to Western blotting.

Western Blotting

Primary monocytes or THP-1 cells lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (Thermo Scientific), or immunoprecipitated proteins were electrophoresed on 4–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies to GMFG (Abgent), β1-integrin (MAB2000) (Millipore), fMLP receptor and CXCR4 (Bioss), β-actin, ubiquitin (P4D1), or α-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); α5-integrin, STXBP4, biotin, or STX6 (Cell Signaling Technology); or STX3, STX4, VAMP2, VAMP3, or VAMP4 (Proteintech Group). Membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and the Amersham Biosciences ECL Western blotting system (GE Healthcare) was used for detection.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

For the detection of monocyte cell surface proteins, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min and then blocked in 10% FBS in PBS for 15 min. The cells were incubated with 20 μg/ml control mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) or monoclonal antibodies to total β1-integrin (both the active and inactive forms, MEM101A) (Novus Biologicals) or α5-integrin (clone NKI-SAM1) (BioLegend) or polyclonal antibodies to fMLP receptor or CXCR4 (Bioss) for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing, the cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen), diluted 1:500, for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were analyzed by EPICS ELITE ESP flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter), and the data were analyzed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Flow Cytometry-based Integrin Internalization and Recycling Assays

The internalization assay was performed as described previously (33). Human monocytes were transfected with control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA for 48 h. The cells (5 × 106 cells/ml) were incubated with anti-β1-integrin antibody (MAB2000; Millipore) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml in HBSS plus 0.5% BSA for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing with ice-cold HBSS, labeled cells were incubated in prewarmed 10% FBS-RPMI medium for the indicated times at 37 °C to allow for integrin internalization. Samples were placed on ice, washed, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were then washed and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The amount of integrin remaining on the cell surface was determined by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Fluorescence intensity of each time point was expressed as a percentage of the value present on the cell surface at time 0 in control negative siRNA-transfected monocytes. To measure recycling, labeled integrins were allowed to internalize at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by stripping of surface integrins with acid buffer (150 mm sodium chloride, glycinate buffer, pH 2.5). Cells were washed with ice-cold HBSS and then incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times to induce the internal integrins to recycle to the cell surface. Cells were then stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above. Recycling of β1-integrin was calculated from the signal intensity remaining in the cells at each time point relative to the control (at time 0) cells that had not been brought back to 37 °C after the first surface acid washing.

Immunofluorescence-based Integrin Internalization and Recycling Assays

For the analysis of integrin internalization by immunofluorescence, siRNA-transfected cells were seeded in 0.5% BSA-RPMI medium on FN-coated (10 μg/ml) 8-well chambers and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Cells were then processed for labeling with β1-integrin antibody and β1-integrin internalization, as indicated above, with further washing by acid buffer (150 mm sodium chloride, glycinate buffer, pH 2.5) to remove the β1-integrin antibody from the cell surface. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 and ice-cold methanol, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody at 4 °C for 30 min to visualize internalized integrin. Cells were stained with DAPI (blue) to detect nuclear DNA. For the analysis of β1-integrin recycling, after the acid wash (150 mm sodium chloride, glycinate buffer, pH 2.5), cells were reincubated at 37 °C for the indicated times to induce the internalized integrin to recycle to the cell surface. Cells were then fixed, followed by permeabilization (to visualize internalized integrins) or without permeabilization, and stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody as described above. The amount of internalized integrin that had recycled back to the cell surface was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Biotinylation-based Recycling Assays

Human monocytes were transfected with control negative siRNA, GMFG siRNA, or STXBP4 siRNA for 48 h. The cells (5 × 107) were washed with ice-cold HBSS twice, and surface proteins were biotinylated on ice using 0.5 mg/ml EZ-LinkTM sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h. The free biotin was quenched with two washes of 50 mm glycine in HBSS. The cells were incubated in 10% FBS-RPMI medium for 30 min at 37 °C to allow internalization. Samples were then returned to ice and washed with ice-cold HBSS three times, and the surface biotin was reduced by incubating the cells with reducing solution (50 mm reducing glutathione, 75 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, and 75 mm NaOH) for two treatments of 15 min each at 4 °C. Free glutathione was then quenched using 5 mg/ml iodoacetamide in HBSS. The cells were then washed with ice-cold HBSS and returned to 37 °C in 10% FBS-RPMI medium for the indicated times to induce internalized integrins to recycle back to the cell surface. The cells were then subjected to a second round of surface reduction with reducing solution to remove the biotin from recycled integrins, followed by a second quenching with iodoacetamide. Cells were then washed and lysed in 300 μl of immunoprecipitation lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Biotinylated cell surface β1-integrin remaining inside the cells was immunoprecipitated from lysates using anti-β1-integrin antibody (MAB2000) (Millipore) and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-biotin antibody or streptavidin-HRP.

Isolation of Plasma Membrane Protein Fraction

The plasma membrane fraction of human monocytes or THP-1 cells was isolated using the Mem-PER Plus Membrane Protein Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Integrin Degradation Assays

Monocytes were incubated with cycloheximide (100 μm) for the indicated time period in the presence or absence of the lysosomal inhibitor leupeptin (500 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) or chloroquine (10 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) or the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (10 μm; Calbiochem). After treatment, cells were subjected to Western blotting analysis using an anti-β1-integrin or α5-integrin antibody.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance for all experiments was determined by Student's paired t test analyses. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

GMFG Is Required for Efficient Chemotaxis in Human Monocytes

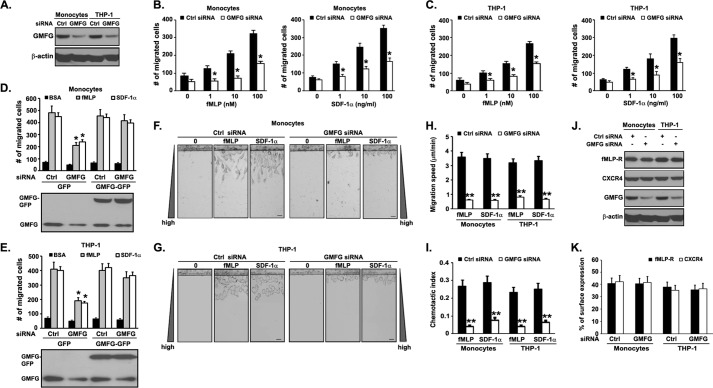

To test our hypothesis that GMFG mediates monocyte migration as well as the mechanisms underlying this process, we first set out to evaluate the effect of GMFG knockdown on the chemotactic ability of human monocytes in response to two well known chemoattractants, fMLP and SDF-1α, using Transwell migration assays. The successful knockdown of GMFG protein expression in human monocytes or THP-1 cells was confirmed by Western blotting analysis (Fig. 1A) (75% reduction in GMFG protein expression in GMFG siRNA-transfected cells). Consistent with previous studies in other types of cells (25, 26), we observed that GMFG siRNA-transfected primary human monocytes or THP-1 cells displayed significantly reduced chemotactic migration toward the chemoattractants fMLP (1–100 nm) or SDF-1α (1–100 ng/ml) at all concentrations tested, when compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 1, B and C). We further determined whether an ectopically expressed GMFG was capable of rescuing the impaired chemotactic cell migration in GMFG knockdown cells. Human monocytes and THP-1 cells were first transiently transfected with a control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA for 48 h, followed by cotransfection of GFP vector or GMFG-GFP expression plasmid for another 24 h. Western blotting analysis confirmed that successful rescue of the GMFG knockdown by ectopic expression of GMFG-GFP plasmid in human monocytes and THP-1 cells (Fig. 1, D and E, bottom). Importantly, the reduced chemotactic cell migration in GMFG siRNA-transfected monocytes or THP-1 cells could be restored to the levels observed in control siRNA-transfected cells by cotransfection of GMFG-GFP plasmid but not by cotransfection with GFP vector only, indicating that the effects of GMFG siRNA on chemotactic migration are specific rather than a potential off-target effect (Fig. 1, D and E).

FIGURE 1.

GMFG knockdown reduces chemotaxis in human monocytes. A, knockdown efficiency of GMFG siRNA in monocytes or THP-1 cells. Cells were transfected with a control negative siRNA (Ctrl) or GMFG siRNA, and lysates were examined by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. B and C, Transwell migration assays were performed on 5-μm pore filters coated with 10 μg/ml FN in primary human monocytes (B) or THP-1 cells (C) transfected with control negative siRNA (Ctrl siRNA) or GMFG siRNA in response to vehicle alone (0.1% BSA) or increasing concentrations of fMLP (1–100 nm) or SDF-1α (1–100 ng/ml). The number of migrated cells was quantitated after 3 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D and E, Transwell migration assays were performed in human monocytes or THP-1 cells cotransfected with control negative siRNA (Ctrl siRNA) or GMFG siRNA and GFP vector or GFP-GMFG vector in response to vehicle alone (0.1% BSA) or fMLP (100 nm) or SDF-1α (100 ng/ml). The number of migrated cells was quantitated after 3 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” F–I, EZ-TAXIScan chemotaxis toward fMLP (100 nm) or SDF-1α (100 ng/ml) in human monocytes or THP-1 cells transfected with control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA. F and G, representative images of migrating cells in a gradient of fMLP or SDF-1α after 3 h. Scale bars, 20 μm. Data are representative of three experiments. H and I, migration speed and chemotactic index were quantified from the captured images during the course of the EZ-TAXIScan chemotaxis assay, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” J, cell surface expression of fMLP receptor (fMLP-R) or chemokine receptor CXCR4 in control negative siRNA- or GMFG siRNA-transfected human monocytes or THP-1 cells. Cells were stained with polyclonal anti-fMLP receptor or anti-CXCR4 antibodies for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing, the cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. K, Western blotting analysis of GMFG, fMLP receptor, and chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in whole-cell lysates from monocytes or THP-1 cells transfected with control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. **, p < 0.01 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells.

To gain further insight into this observation, we examined the dynamics of directional migration in cells transfected with control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA using an EZ-TAXIScan system, which allows real-time visualization of cell movements and makes time-lapse recording of the speed and directionality of individual cells toward linear gradients of chemoattractants over time. We observed that, in contrast to control siRNA-transfected cells, GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells revealed a marked impairment in their chemotactic behavior, because GMFG knockdown cells migrated over a much shorter distance with slower speed toward the fMLP or SDF-1α gradient when compared with control siRNA-transfected monocytes (Fig. 1, F and G, and supplemental Movies S1–S8). However, GMFG knockdown cells were able to sense the chemoattractant gradient, because these cells were seen to quickly form protrusions and polarize toward chemoattractants after the initiation of chemotaxis (supplemental Movies S1–S8). To perform a detailed analysis of time-dependent chemotactic ability, we measured mean migration speed and chemotactic index (directionality) in GMFG knockdown and control negative siRNA-transfected cells. Quantification by cell tracking revealed that GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells displayed significantly decreased migration speed and directionality during the chemotaxis, indicating that GMFG is important for monocyte chemotaxis (Fig. 1, H and I). Furthermore, these defects were not due to alteration in total or cell surface levels of fMLP receptor or chemokine receptor CXCR4, because knockdown of GMFG did not alter total or cell surface levels of these relevant receptors in human monocytes or THP-1 cells compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 1, J and K).

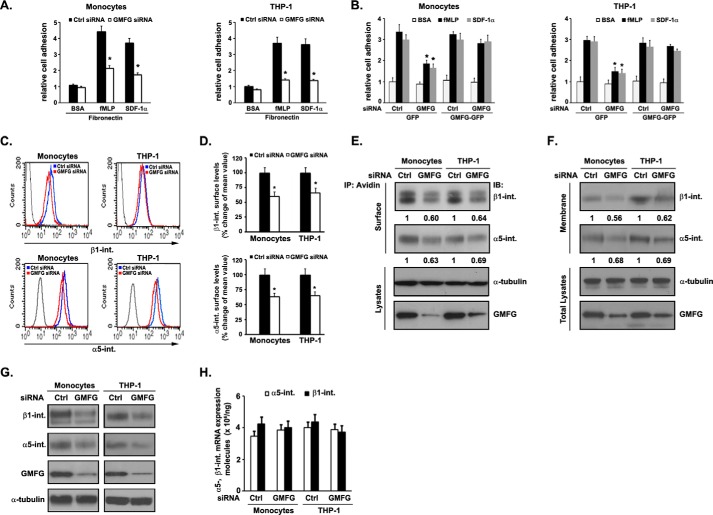

GMFG Regulates α5β1-integrin-mediated Chemoattractant-stimulated Adhesion in Human Monocytes

Integrin-mediated cell adhesion to the endothelium or the extracellular matrix is a prominent mechanism for monocyte recruitment to sites of inflammation. Therefore, we next sought to determine whether the effects of GMFG on chemotaxis might occur through regulation of monocyte adhesion. For this purpose, the effect of knockdown of GMFG on monocyte adhesion was determined with adhesion assays that measure the fraction of cells that attach to an FN-coated surface in steady-state conditions or after stimulation by fMLP or SDF-1α. We found that knockdown of GMFG had no significant effect on adhesion to FN in the absence of stimulation. However, when GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells were stimulated with fMLP or SDF-1α, their adhesion to FN was significantly reduced compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2A). Importantly, reduced adhesion in GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells could be rescued to the levels observed in control siRNA-transfected cells by cotransfection with GMFG-GFP vector but not by cotransfection with GFP vector only (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that impaired adhesion is indeed due to suppression of endogenous GMFG expression. These results clearly indicated that GMFG regulates α5β1-integrin-mediated adhesion and that the inhibition of monocyte migration observed upon knockdown of GMFG may be a consequence of reduced adhesion.

FIGURE 2.

GMFG knockdown decreases chemoattractant-stimulated cell adhesion to FN and cell surface expression of α5β1-integrin in human monocytes. Human monocytes or THP-1 cells were transfected with control negative siRNA (Ctrl siRNA) or GMFG siRNA for 48 h. A, siRNA-transfected human monocytes or THP-1 cells were subjected to adhesion assays on 10 μg/ml FN-coated wells (in triplicate samples) in the absence (Ctrl) or presence of fMLP (100 nm) or SDF-1α (100 ng/ml). Values were calculated as -fold increase over levels in unstimulated cells treated with control negative siRNA. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars). *, p < 0.05 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. B, human monocytes or THP-1 cells were cotransfected with control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA and GFP vector or GFP-GMFG vector and then subjected to an in vitro adhesion assay on 10 μg/ml FN-coated wells (in triplicate samples) in the absence or presence of 100 nm fMLP or 100 ng/ml SDF-1α. Values were calculated as -fold increase over levels in unstimulated cells treated with control negative siRNA. Data represent three independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 compared with control negative siRNA-transfected cells. C, representative flow cytometry results for cell surface expression of β1-integrin (top panels) or α5-integrin (bottom panels) in siRNA-transfected human monocytes or THP-1 cells. Cells were labeled with antibodies to β1-integrin (both the active and inactive forms, MEM101A) or α5-integrin (NKI-SAM1) for 1 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody, and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. D, quantification of integrin cell surface expression flow cytometry results as in C. Data represent the mean fluorescence intensity ± S.D. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. E, cell surface-biotinylated β1-integrin or α5-integrin in siRNA-transfected human monocytes or THP-1 cells. Surface-biotinylated proteins were precipitated using avidin beads, followed by Western blotting analysis with β1-integrin (MAB2000) or α5-integrin (4705P, Cell Signaling) antibodies (top panels). 20% input total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting analysis of α-tubulin or GMFG (bottom panels). α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. The densitometric analysis of the relative quantification of β1- and α5-integrin signal intensities (normalized to control siRNA-transfected integrin signal set at 1) is shown below each blot. F, plasma membrane expression of β1- or α5-integrin in siRNA-transfected monocytes or THP-1 cells. The plasma membrane fraction of cells was isolated and then subjected to Western blotting analysis with β1-integrin (MAB2000) or α5-integrin (4705P, Cell Signaling) antibodies (top panels). 20% input total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting analysis of α-tubulin or GMFG (bottom panels). α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. The densitometric analysis of the relative quantification of β1- and α5-integrin signal intensities (normalized to control siRNA-transfected integrin signal set at 1) is shown below each blot. G, Western blotting analysis of β1-integrin, α5-integrin, and GMFG expression in whole-cell lysates from siRNA-transfected monocytes or THP-1 cells. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. H, quantitative PCR analysis of the expression of α5-integrin and β1-integrin transcripts in control siRNA- or GMFG siRNA-transfected human monocytes or THP-1 cells. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. IP, immunoprecipitation.

Cell migration and adhesion are affected by surface integrin levels (34). Therefore, we investigated whether the reduced cell adhesion induced by knockdown of GMFG was associated with alteration of specific integrins. We restricted our analysis to the integrins expressed in human monocytes that are most critical for monocyte adhesion to FN (α5- and β1-integrins). First, flow cytometry analysis indicated that GMFG knockdown in human monocytes or THP-1 cells resulted in a decrease in the surface levels of α5- and β1-integrin (both the active and inactive forms, MEM101A) compared with control negative siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2, C and D). We further determined the surface levels of α5- and β1-integrin in GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells using cell surface biotinylation. Biotinylated surface proteins were pulled down with avidin beads and then examined by Western blotting using α5- and β1-integrin antibodies. Consistent with flow cytometry analysis results, cell surface biotinylation showed that GMFG knockdown resulted in markedly decreased levels of surface α5- and β1-integrin in monocytes or THP-1 cells (Fig. 2E). Moreover, Western blotting analysis of plasma membrane protein extracts confirmed reduced membrane levels of α5- and β1-integrin in GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells (Fig. 2F). These results strongly suggest that knockdown of GMFG expression reduces the abundance of α5- and β1-integrin at the cell surface in human monocytes and THP-1 cells. Finally, Western blotting analysis revealed that knockdown of GMFG in monocytes or THP-1 cells led to markedly decreased total protein levels of mature (Mr 125,000) β1-integrin and α5-integrin compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2G). These reduced α5- and β1-integrin protein levels were not due to insufficient messenger RNA transcription, because quantitative Q-PCR analysis showed that the levels of α5- and β1-integrin transcripts were unchanged in GMFG knockdown cells compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2H). Together, these results indicate that modification of GMFG expression levels can serve to regulate the protein levels of α5β1-integrin by posttranscriptional events, such as altered α5β1-integrin degradation.

GMFG Overexpression Enhances Chemoattractant-stimulated Migration and Adhesion to FN in Human Monocytes

To confirm the role of GMFG in α5β1-integrin-mediated monocyte migration and adhesion, we next examined the effect of GMFG overexpression in monocytes or THP-1 cells. Western blotting analysis showed that GFP-tagged GMFG was successfully transfected into monocytes or THP-1 cells (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the results of GMFG knockdown experiments, GMFG overexpression led to a significant increase in chemotactic cell migration toward fMLP or SDF-1α compared with the GFP control-transfected cells (Fig. 3B). Moreover, GMFG overexpression significantly enhanced cell adhesion to FN after stimulation with fMLP or SDF-1α (Fig. 3C). Flow cytometry analysis did not demonstrate any significant differences in cell surface expression of α5- or β1-integrin between GFP-transfected and GMFG-GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 3D). However, overexpression of GMFG appeared to slightly increase total cellular protein levels of α5- and β1-integrin compared with GFP vector only-transfected cells (Fig. 3E). Together, these results indicate that overexpression of GMFG enhances chemotactic cell migration and cell adhesion in monocytes.

FIGURE 3.

GMFG overexpression enhances chemoattractant-stimulated cell migration and adhesion to FN. Human monocytes or THP-1 cells were transfected with GFP vector or GFP-tagged GMFG plasmid for 48 h. A, Western blotting analysis of expression of GMFG or GMFG-GFP in monocytes or THP-1 cells. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. B, Transwell migration assays were performed on 5-μm pore filters coated with 10 μg/ml FN in transfected primary human monocytes or THP-1 cells in the absence (Ctrl) or presence of fMLP (100 nm) or SDF-1α (100 ng/ml). The number of migrated cells was quantitated after 3 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars). *, p < 0.05 compared with control GFP-transfected cells. C, transfected human monocytes or THP-1 cells were subjected to adhesion assays on 10 μg/ml FN-coated wells (in triplicate samples) in the absence or presence of fMLP (100 nm) or SDF-1α (100 ng/ml). The number of attached cells was quantitated after 15 min, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data represent the mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 compared with control GFP-transfected cells. D, representative flow cytometry results for cell surface expression of α5- or β1-integrins in GFP- or GMFG-GFP-transfected human monocytes. Monocytes were incubated with antibodies to α5-integrin or β1-integrin (both the active and inactive forms, MEM101A) for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing, the cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. E, Western blotting analysis of α5-integrin or β1-integrin in whole-cell lysates from GFP- or GMFG-GFP-transfected monocytes or THP-1 cells. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control.

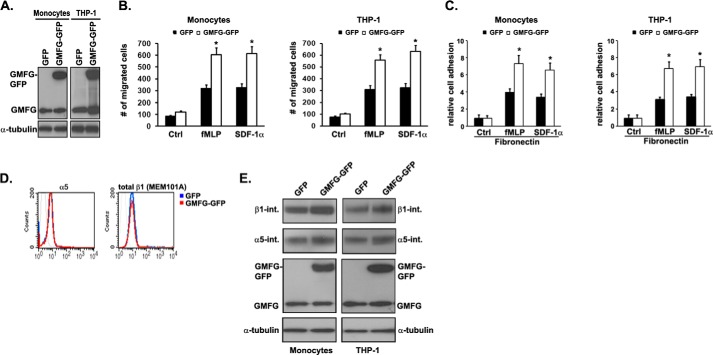

GMFG Is Required for the Maintenance of α5β1-Integrin Stability

To investigate whether GMFG might influence the stability of α5- and β1-integrin proteins, we performed integrin degradation assays. For these experiments, we inhibited protein synthesis by the addition of cycloheximide and then assessed the steady-state levels of β1- and α5-integrins by Western blotting. We found that β1- and α5-integrin protein levels were markedly decreased after 4 h of cycloheximide treatment in GMFG knockdown monocytes but remained relatively high in control negative siRNA-transfected monocytes over a 6-h time period, indicating that the rate of both β1- and α5-integrin protein degradation was markedly accelerated in GMFG knockdown monocytes compared with control siRNA-transfected monocytes (Fig. 4A). Next, to determine the proteolytic pathways that might be involved in the degradation of β1- and α5-integrin proteins, we treated GMFG knockdown cells with the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 or the lysosomal inhibitor leupeptin or chloroquine. Western blotting analysis revealed that proteasome inhibition largely reversed the degradation of β1- and α5-integrin caused by GMFG knockdown (Fig. 4B). Lysosomal inhibitors also attenuated β1- and α5-integrin degradation, although to a lesser extent (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that GMFG knockdown-related increases in the degradation rate of β1- or α5-integrin are mediated by the proteasome degradation pathway and that lysosomes are also involved in GMFG knockdown-related integrin turnover.

FIGURE 4.

GMFG knockdown enhances degradation of α5- and β1-integrin in human monocytes. A and B, α5-integrin and β1-integrin degradation in GMFG knockdown cells. Human monocytes were transfected with control negative siRNA (Ctrl siRNA) or GMFG siRNA for 48 h. siRNA-transfected cells were treated with 100 μm cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated time periods (A) or with cycloheximide (100 μm) for 6 h in the presence of DMSO, the lysosomal inhibitors leupeptin (Leu; 500 μg/ml) or chloroquine (Chlo; 10 μm), or the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (10 μm), as indicated. Relative quantification of degradation of β1- and α5-integrin is shown in the bottom panels. The signal intensities of β1- and α5-integrin were standardized to the signal intensity of β-actin and normalized to 100% at time 0. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. **, p < 0.01 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. B, total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting analysis using anti-α5- and β1-integrin antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Relative quantification of degradation of β1- and α5-integrin is shown in the lower panels. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. **, p < 0.01 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. C and D, THP-1 cells were transfected with control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA and GFP vector or GFP-GMFG vector for 48 h and then treated with DMSO (C) or 10 μm MG132 for an additional 2 h (D). The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-β1-integrin antibody, and ubiquitinated β1-integrin was detected by Western blotting using anti-ubiquitin antibody. Relative quantification of ubiquitinated β1-integrin levels is shown in the bottom panels. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. NS, no statistical significance. E and F, stability of α5- and β1-integrin after fMLP (E) or SDF-1α (F) stimulation of GMFG knockdown cells. siRNA-transfected human monocytes were treated with fMLP (100 nm) or SDF-1α (100 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting analysis using anti-α5- and β1-integrin antibody. GMFG was used as a loading control.

Ubiquitin-dependent proteasome degradation is an important process involved in protein down-regulation. To investigate whether the decreased levels of β1- and α5-integrin protein expression observed in GMFG knockdown monocytes may result from ubiquitin-mediated degradation, we immunoprecipitated endogenous β1- or α5-integrin in THP-1 cells transfected with GMFG siRNA or GMFG-GFP vector and subjected the immunoprecipitates to Western blotting analysis with ubiquitin antibody. We observed that ubiquitinated β1-integrin levels were significantly increased in GMFG knockdown cells, whereas the ubiquitinated levels were dramatically reduced in GMFG-overexpressing cells compared with the control siRNA- or GFP vector-transfected cells (Fig. 4C). These results were verified by assessing the effect of proteasomal inhibitor MG132 on ubiquitination of β1-integrin steady-state levels in GMFG siRNA- or GMFG-GFP vector-transfected cells (Fig. 4D). MG132 treatment caused further accumulation of ubiquitinated β1-integrin levels in GMFG-overexpressing cells to the levels observed in control GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 4D), indicating that GMFG indeed mediated β1-integrin ubiquitination. However, Western blotting analysis of α5-integrin immunoprecipitates using anti-ubiquitin antibody in GMFG siRNA-, GMFG-GFP vector-, control siRNA-, or GFP vector-transfected cells failed to detect a ubiquitin signal (data not shown), indicating that GMFG mediates the ubiquitination of β1-integrin, but not α5-integrin, in human monocytes. Finally, to investigate whether GMFG knockdown decreases β1- and α5-integrin stability during cell migration, we determined the degradation kinetics of β1- and α5-integrin proteins in response to fMLP or SDF-1α stimulation. Western blotting analysis showed that both β1- and α5-integrin levels were dramatically decreased at late time point treatments with fMLP or SDF-1α in GMFG knockdown monocytes compared with control siRNA-transfected monocytes (Fig. 4, E and F). Together, these results suggest that GMFG regulates monocyte migration and adhesion by preventing β1-integrin degradation through ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal and lysosomal pathways.

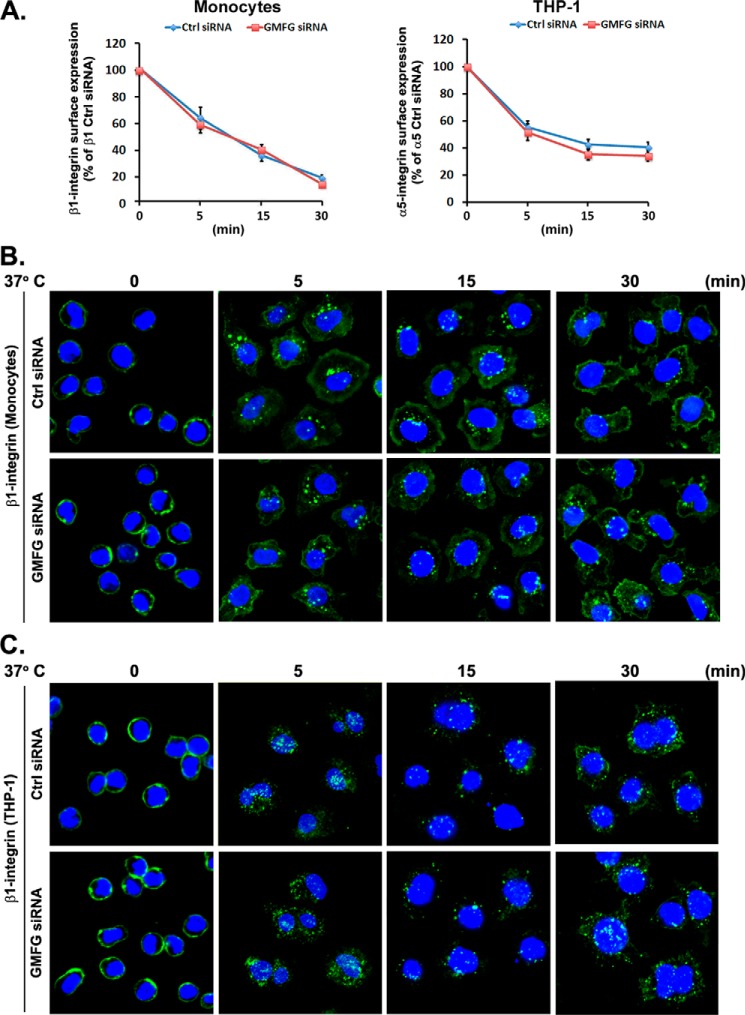

GMFG Is Not Involved in β1-Integrin Endocytosis

Having implicated GMFG as a mediator of β1-integrin turnover, and knowing that β1-integrin turnover is also affected by the dynamic regulation of integrin internalization and recycling (which plays a pivotal role in cell adhesion and motility) (35, 36), we hypothesized that GMFG knockdown might affect β1-integrin internalization or recycling. To functionally address this point, we first performed antibody-based internalization assays in GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells using flow cytometry. After surface-labeling with β1-integrin antibody at 4 °C, internalization was initiated by transferring cells to serum-free medium at 37 °C for the indicated time period. To quantify this process, we measured the surface-remaining β1-integrin using flow cytometry. We observed no significant differences in the amount of labeled surface-remaining β1-integrin following endocytosis in GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells when compared with control siRNA-transfected monocytes (Fig. 5A). Immunofluorescence analyses of β1-integrin following endocytosis at 37 °C over time demonstrated similar patterns of endocytosis in GMFG knockdown monocytes or THP-1 cells compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 5, B and C). These results indicated that GMFG has no effect on the internalization of β1-integrin in monocytes. Therefore, GMFG may instead regulate β1-integrin turnover by altering its exocytosis.

FIGURE 5.

GMFG knockdown does not affect β1-integrin endocytosis. Human monocytes or THP-1 cells were transfected with control negative siRNA(Ctrl siRNA) or GMFG siRNA. Forty-eight h after transfection, cell surface β1-integrin was labeled with anti-β1-integrin antibody at 4 °C for 1 h, followed by incubation of cells at 37 °C for the indicated time periods to induce internalization. A, analysis of β1-integrin internalization in siRNA-transfected human monocytes or THP-1 cells by flow cytometry. Surface-labeled cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody at 4 °C, followed by quantification of surface-remaining β1-integrin. Results are shown as the percentage of the integrin surface expression observed in control negative siRNA-transfected cells before internalization (i.e. the 0-min time point was set at 100%). Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three experiments. B and C, analysis of β1-integrin internalization in siRNA-transfected human monocytes (B) or THP-1 cells (C) by immunofluorescence. Cells with surface-labeled β1-integrin were incubated at 37 °C for the indicated time periods to induce internalization, followed by stripping of surface-bound antibody by acid washing. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody at 4 °C. Nuclear DNA was labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm.

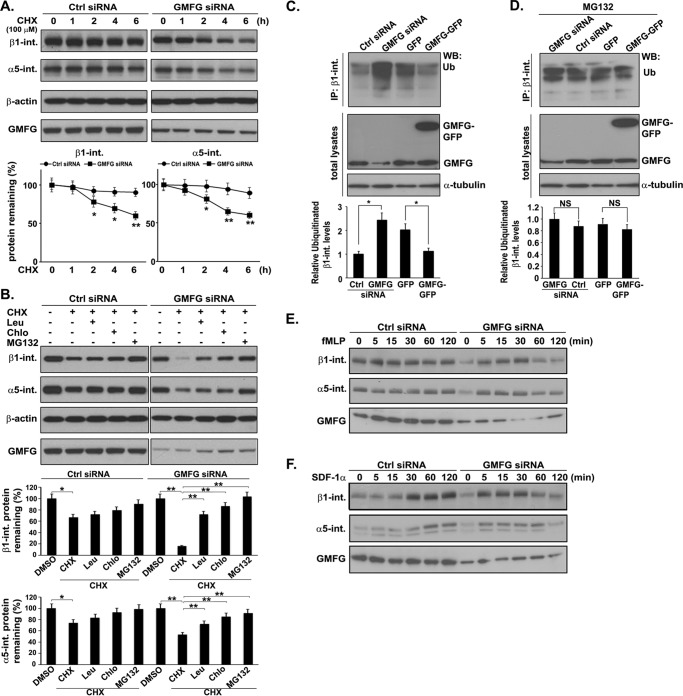

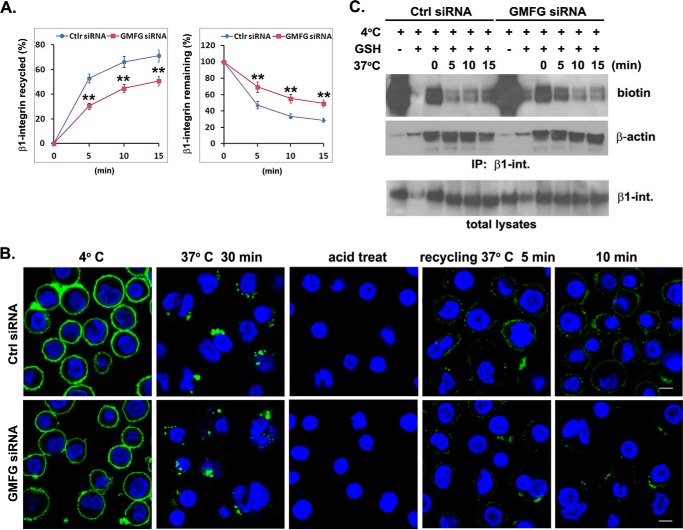

GMFG Is Required for β1-Integrin Recycling

Given that increased β1-integrin degradation in GMFG knockdown monocytes appears not to result from altered β1-integrin internalization, we next examined the role of GMFG in exocytic trafficking of β1-integrin to the plasma membrane using antibody-based, immunofluorescence-based, and biotinylation-based recycling assays. We first performed an antibody-based recycling assay in control negative siRNA- or GMFG siRNA-transfected monocytes. In this assay, monocytes with internalized, antibody-labeled β1-integrin were surface-stripped of antibody and then transferred to serum-containing medium at 37 °C for the indicated time period to allow recycling, followed by incubation with a fluorescently labeled second antibody to detect those integrin molecules that had been initially internalized and subsequently recycled to the cell surface. Flow cytometry analysis showed that GMFG knockdown monocytes had reduced levels of internalized β1-integrin rapidly returning to the cell surface and increased levels of internalized β1-integrin remaining inside the cell, compared with control siRNA-transfected monocytes, indicating a role for GMFG in β1-integrin recycling (Fig. 6A). These data were further confirmed by immunofluorescence analyses, which demonstrated reduced β1-integrin trafficking back to the cell surface following chase with serum at 37 °C in GMFG knockdown cells, compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 6B). Finally, an integrin recycling assay employing cell surface biotinylation analysis revealed that the fraction of internalized biotinylated β1-integrin remaining inside the cells was remarkably increased at the 5-min time point in GMFG knockdown cells compared with control siRNA-transfected cells, indicating a retardation of the efficient recycling of β1-integrin back to the plasma membrane in GMFG knockdown cells (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results indicate that GMFG regulates β1-integrin recycling without affecting β1-integrin endocytosis.

FIGURE 6.

GMFG knockdown inhibits efficient β1-integrin recycling to the cell surface of human monocytes. A and B, human monocytes were transfectedwith control negative siRNA (Ctrl siRNA) or GMFG siRNA. Forty-eight h after transfection, cell surface β1-integrin was labeled with anti-β1-integrin antibody at 4 °C, followed by incubation of cells at 37 °C for 30 min to induce internalization. Cells were then acid-washed to remove the remaining surface-bound labeled integrin antibody, and the internalized β1-integrin was chased back to the cell surface at 37 °C for the indicated time periods. A, antibody-based assay of β1-integrin recycling. Cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody at 4 °C, followed by quantification of surface β1-integrin by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three experiments. **, p < 0.01 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. B, immunofluorescence-based assay of β1-integrin recycling. Cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody without permeabilization to examine β1-integrin trafficking back to the cell surface. Nuclear DNA was labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 100 μm. C, biotinylation-based assay of β1-integrin recycling. Monocytes transfected with control negative siRNA or GMFG siRNA were surface-labeled with 0.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin at 4 °C for 1 h, and then internalization was induced at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells were exposed to GSH solution at 4 °C to remove surface biotin and then chased at 37 °C for the indicated time periods to allow recycling, followed by a second reduction with glutathione. Biotinylated cell surface proteins remaining inside the cells were immunoprecipitated using an anti-β1-integrin antibody and subsequently detected by Western blotting analysis using an anti-biotin or anti-β-actin antibody. Samples of the total lysates are shown in the bottom panel; each sample corresponds to 5% of the cell lysate used in each immunoprecipitation. The blots are representative of three independent experiments. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

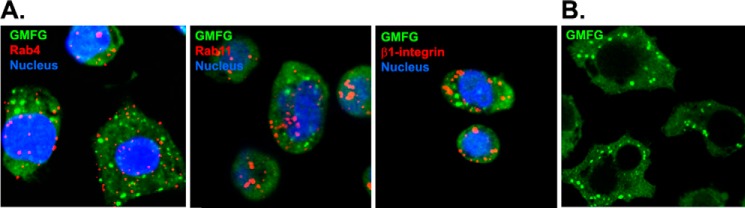

GMFG Interacts with STXBP4 and STX4

Although endocytic recycling of β1-integrin is dependent upon a number of diverse protein families and cytoskeletal adaptor proteins, including small GTPases of the Arf and Rab families, the most studied of the Rab GTPases are Rab4 and Rab11, which play key roles in β1-integrin rapid and slow recycling, respectively. Therefore, we examined whether GMFG interacts with Rab4 and Rab11 and mediates β1-integrin recycling in human monocytes. Our immunofluorescence assays showed that GMFG did not colocalize with Rab4, Rab11, or β1-integrin under steady-state conditions (Fig. 7A). However, the intracellular vesicular-like distribution of GMFG suggests that GMFG might be associated with other proteins that mediate constitutive exocytic trafficking of β1-integrin (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

The localization of GMFG in human monocytes. Human monocytes were seeded on FN-coated chambered coverglass for 20 min. Attached cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with the indicated antibodies. A, confocal images show endogenous GMFG (green), Rab4 or Rab11 (red) (rapid and slow recycling markers), or β1-integrin (red) and nuclear DNA (blue; DAPI) in human monocytes. B, confocal images show GMFG distribution in human monocytes. Scale bar, 10 μm.

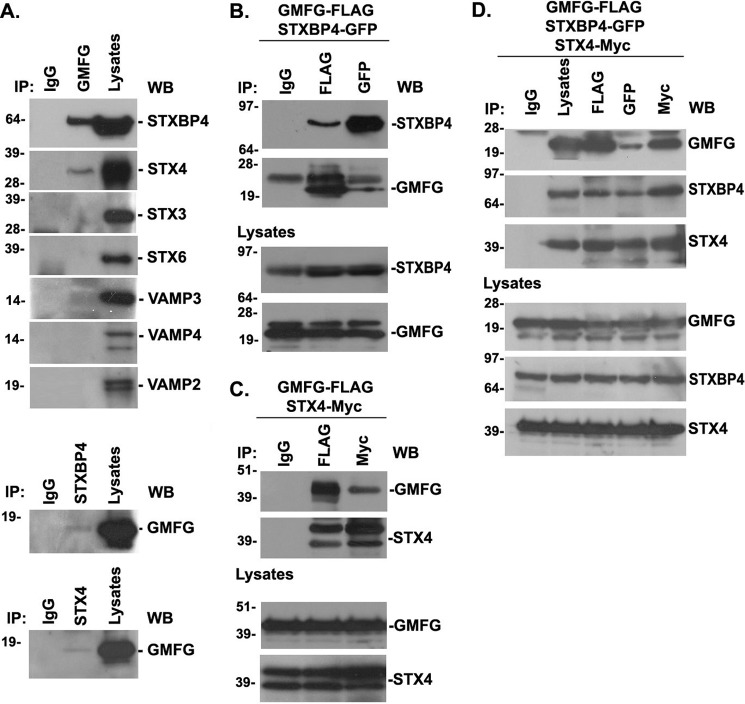

To gain further insights into the role of GMFG in β1-integrin recycling, we attempted to identify its potential binding partners that relate to GMFG function. In recent studies, SNARE proteins have emerged as regulators in exocytic trafficking of integrins by mediating membrane fusion (37). The SNARE proteins STX3, STX4, and STX6 have been reported to mediate β1-integrin exocytic trafficking to the plasma membrane in macrophages and endothelial cells (12). Therefore, we screened the possible interaction of GMFG with these SNARE proteins and VAMP proteins in monocytes by performing endogenous coimmunoprecipitation assays using a specific GMFG antibody. We observed that the STX4-binding protein STXBP4 was detected strongly by anti-GMFG immunoprecipitation, and STX4 was also weakly detected, whereas all other syntaxins (STX3 and STX6) or VAMP isoforms (VAMP2, VAMP3, and VAMP4) were not detectable in GMFG coimmunoprecipitates in human monocytes (Fig. 8A, top). Conversely, interaction with GMFG was barely detectable in coimmunoprecipitates using anti-STX4 or anti-STXBP4 antibodies (Fig. 8A, bottom), indicating that these antibodies may not be suitable for immunoprecipitation assays. Therefore, to further test this interaction, we exogenously coexpressed GFP-tagged STXBP4 or Myc-tagged STX4 together with FLAG-tagged GMFG in HEK-293T cells. Immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP or anti-Myc antibody efficiently precipitated GMFG protein (Fig. 8, B and C). Conversely, immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody precipitated STXBP4 or STX4 (Fig. 8, B and C, respectively). Furthermore, coimmunoprecipitation analysis following coexpression of FLAG-tagged GMFG together with Myc-tagged STX4 and GFP-tagged STXBP4 in HEK-293T cells demonstrated that GMFG was detected in a complex with STXBP4 and STX4 (Fig. 8D). These data indicate that GMFG is specifically associated with both endogenous SNARE proteins STX4 and STXBP4 in human monocytes. We were unable to detect a clear colocalization between GMFG and STX4 or STXBP4 in THP-1 cells using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy (data not shown), suggesting that these STX4 or STXBP4 antibodies might also not be suitable for immunofluorescence assays. However, our coimmunoprecipitation results suggest that GMFG-mediated β1-integrin trafficking may be related to its association with STX4 and STXBP4.

FIGURE 8.

GMFG interacts with STXBP4 and STX4 in human monocytes. A, endogenous GMFG was immunoprecipitated (IP) from THP-1 cells, and precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting (WB) using anti-STXBP4, anti-STX, or anti-VAMP antibodies as indicated (top panel). Endogenous STXBP4 and STX4 were immunoprecipitated from THP-1 cells, and precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GMFG antibody (bottom panel). Samples of the total lysate are shown in the right lane, and nonspecific mouse IgG was used as a negative control. B and C, HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with FLAG-tagged GMFG and GFP-tagged STXBP4 (B) or FLAG-tagged GMFG and Myc-tagged STX4 (C). Forty-eight h after transfection, cells were harvested and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG, anti-GFP, or anti-Myc antibodies, and precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-GMFG, anti-STXBP4, or anti-STX4 antibodies. Samples of the total lysates are shown in the bottom panel; each sample corresponds to 5% of the cell lysate used in each immunoprecipitation. D, HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with FLAG-tagged GMFG, GFP-tagged STXBP4, and Myc-tagged STX4. Forty-eight h after transfection, cells were harvested and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG, anti-GFP, or anti-Myc antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-GMFG, anti-STXBP4, or anti-STX4 antibodies. Samples of the total lysates are shown in the bottom panel; each sample corresponds to 5% of the cell lysate used in each immunoprecipitation.

STXBP4 Facilitates Cell Directional Migration and β1-Integrin Recycling

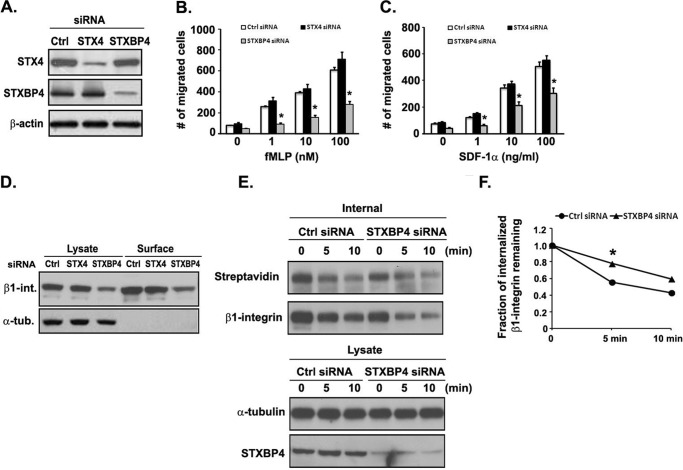

Given that GMFG interacts with STX4 and STXBP4, we next investigated whether the GMFG associated with STX4 or STXBP4 is involved in directional migration of monocytes by mediating β1-integrin endocytic trafficking to the cell surface. To test this possibility, we knocked down endogenous STX4 or STXBP4 to compare the role of each of these two molecules in human monocyte migration and β1-integrin recycling. STX4 or STXBP4 siRNA knockdown efficiency was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 9A). In Transwell migration assays, we observed that STXBP4 knockdown significantly reduced chemotactic migration of THP-1 cells toward fMLP or SDF-1α, when compared with control siRNA-transfected cells, whereas knockdown of STX4 had no effect on monocyte migration (Fig. 9, B and C). We next evaluated whether knockdown of STX4 or STXBP4 expression in THP-1 cells affected cell surface β1-integrin protein expression using cell surface biotinylation. Knockdown of STXBP4, but not STX4, markedly reduced the surface expression level of β1-integrin (Fig. 9D). Given that down-regulation of STXBP4, but not STX4, decreased the surface levels of β1-integrin and reduced monocyte migration, we further examined the role of STXBP4 in β1-integrin recycling using a biotinylation-based recycling assay. Knockdown of STXBP4 substantially increased the fraction of internalized biotinylated β1-integrin remaining inside the cells at the 5-min time point in STXBP4 knockdown cells compared with control siRNA-transfected cells, demonstrating that recycling of β1-integrin back to the plasma membrane was impaired in STXBP4 knockdown cells (Fig. 9, E and F). Taken together, our results support the conclusion that GMFG interacts with STXBP4 to regulate cell migration and β1-integrin recycling and that the loss of either GMFG or STXBP4 can impair β1-integrin trafficking back to the cell surface, disrupting directional monocyte migration.

FIGURE 9.

Knockdown of STXBP4 inhibits human monocyte migration and is correlated with inefficient β1-integrin recycling to the cell surface. A, knockdown efficiency of STXBP4 and STX4 siRNA in THP-1 cells. Cells were transfected with a control negative siRNA (Ctrl), STX4 siRNA, or STXBP4 siRNA, and lysates were examined by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. B and C, Transwell migration assays were performed on 5-μm pore filters coated with 10 μg/ml FN in THP-1 cells transfected with control negative siRNA (Ctrl siRNA), STXBP4 siRNA, or STX4 siRNA in response to vehicle alone (0.1% BSA) or increasing concentrations of fMLP (1–100 nm) or SDF-1α (1–100 ng/ml). The number of migrated cells was quantitated after 3 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. D, THP-1 cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were surface-labeled with 0.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin at 4 °C for 1 h. Surface-biotinylated proteins were then isolated using streptavidin beads, followed by Western blotting analysis of β1-integrin. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. E, biotinylation-based assay of β1-integrin recycling. THP-1 cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were biotinylated and allowed to internalize surface proteins for 30 min at 37 °C. Surface biotin was removed by reduction (glutathione solution), and internalized proteins were chased at 37 °C for the indicated time periods to allow recycling back to the surface. Surface biotin was reduced again, and cells were lysed. Top, biotinylated cell surface proteins remaining inside the cells were immunoprecipitated using an anti-β1-integrin antibody and subsequently detected by Western blotting analysis using streptavidin-HRP or β1-integrin antibody. Bottom, samples of the total lysates; each sample corresponds to 5% of the cell lysate used in each immunoprecipitation. Shown is a representative Western blot of one experiment (n = 3). α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. F, quantification of β1-integrin recycling determined by densitometry signal as in E. The fraction of internalized β1-integrin remaining was quantified from the signal intensity of internalized protein at each time point relative to control siRNA-transfected cells that had not been placed at 37 °C after the first surface reduction.

Discussion

Because the endocytic trafficking of integrins toward the leading edge has been established to be a critical step during leukocyte migration (38), finding the molecular mechanisms that coordinate regulation of integrin recycling and degradation has been a matter of considerable research interest. Here we provide evidence demonstrating the important role of GMFG in directional monocyte migration through protecting β1-integrin from ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation and maintaining β1-integrin stability during cell migration as well as promoting β1-integrin recycling back to the plasma membrane. These effects of GMFG may be coordinated through association with STXBP4 to modulate fusion of β1-integrin-containing vesicles with the leading plasma membrane during chemotactic migration of monocytes.

Directional migration requires an asymmetric distribution of actin cytoskeletal and adhesive molecules, such as integrins (39–42), but the underlying regulatory mechanisms are not clearly understood. Recently, a growing amount of evidence has begun to emerge suggesting that actin filaments (cytoskeleton) play essential roles in endocytic vesicle trafficking and that actin-regulatory proteins are required for endocytic integrin trafficking and regulating integrin-mediated cell motility. These include the Arp2/3 regulator proteins N-WASP (43), cortactin (44), annexin A2 (45), and Arp2/3 (46, 47). GMFG, another Arp2/3 regulator protein, has been reported to be required for efficient directional migration of neutrophils and T-lymphocytes through regulation of actin cytoskeletal and integrin-mediated adhesion (25, 26). Consistent with this, our study confirmed that GMFG is also required for human monocyte chemotactic migration. We found that GMFG knockdown was correlated with a significant reduction in chemoattractant-stimulated adhesion to FN, the extracellular matrix substrate of α5β1-integrin. Although a previous study reported that GMFG silencing enhanced cell surface β1-integrin and led to increased cell adhesion in T-lymphocytes (26), our findings from flow cytometry, cell surface biotinylation, and plasma membrane protein extract analyses revealed decreased cell surface levels of β1- and α5-integrin in human monocytes and THP-1 cells following GMFG knockdown. This discrepancy regarding the effect of GMFG on cell adhesion is probably due to the use of different experimental conditions and cell types. Lippert and Wilkins (26) examined the role of GMFG on cell adhesion under steady-state conditions in T-lymphocytes, whereas we performed studies of chemoattractant-stimulated adhesion in monocytes to FN. Importantly, our findings indicate that reduced protein levels of β1- and α5-integrin in GMFG knockdown cells appear to be due to accelerated integrin degradation during monocyte directional migration. Moreover, the ectopic expression of GMFG markedly enhanced chemotactic cell migration and cell adhesion in monocytes and THP-1 cells although it showed no effects on cell surface expression levels of α5-or β1-integrin, further supporting the results from GMFG knockdown studies.

The fate of internalized integrin trafficking for degradation or recycling back to the plasma membrane is determined in early sorting endosomes (48) and requires the concerted action of diverse protein families, including kinases, actin-associated proteins, sorting nexins, and small GTPases of the Arf and Rab families (49, 50). Our findings revealed that GMFG knockdown reduced total and cell surface levels of β1-integrin and accelerated ubiquitin-mediated β1-integrin degradation, indicating that GMFG is probably involved in β1-integrin sorting rather than in influencing β1-integrin transcript. Indeed, the ubiquitination of α5β1-integrin has recently arisen as a crucial regulator of cell adhesion and migration via sorting integrin to the lysosome (51, 52). We have shown that knockdown of GMFG markedly increases ubiquitination of β1-integrin, whereas overexpression of GMFG decreases its ubiquitination. These results suggest that one of the important functions of GMFG is to maintain α5β1-integrin stability through regulation of β1-integrin ubiquitination. These findings might explain the observed impairments in chemoattractant-stimulated cell adhesion as well as in directional cell migration upon GMFG knockdown in monocytes, indicating that β1-integrin functions are severely impaired when their degradation and recycling are not well controlled by GMFG. Moreover, overexpression of GMFG induced remarkable decreases in ubiquitination of β1-integrin, which was reversed by proteasomal inhibitor, indicating that GMFG prevents β1-integrin ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. However, further studies are needed to identify the underlying mechanism of GMFG-regulated α5β1-integrin degradation and ubiquitination.

Effective β1-integrin trafficking from the rear of the cell, with timely delivery to the membrane at the leading edge, is critical in a migrating cell. Impairment of the exocytic trafficking of integrins dramatically affects cell adhesion and polarity and leads to attenuation of the directionality of cell migration (10, 34, 53). Considering these studies together with our finding that GMFG is required to maintain β1-integrin stability during monocyte chemotactic migration, we speculate that GMFG may play a role in β1-integrin endocytic trafficking. In support of this hypothesis, our recycling assays of GMFG knockdown monocytes revealed impairment in β1-integrin recycling following internalization and a marked increase in β1-integrin degradation, whereas β1-integrin endocytic internalization events were not affected. Similar to our observations, others have demonstrated that the sorting nexin protein SNX17 regulates the β1-integrin recycling-trafficking step that sequesters β1-integrins away from traffic destined for lysosomal degradation and facilitates integrin recycling back to the membrane (54, 55). Hence, the ability to sequester β1-integrin away from degradation in lysosomes and toward entry into recycling endosomes represents an important regulatory process during monocyte migration.

Endocytic recycling of β1-integrin requires a number of steps, including docking, sorting, and delivery of β1-integrin-containing vesicles recycling to the plasma membrane by trafficking machineries (34, 39, 53, 56). However, the final steps that control fusion of β1-integrin recycling endosomes with the plasma membrane remain poorly understood. It has recently emerged that the SNARE family of proteins is involved in all membrane-trafficking pathways by regulating membrane fusion events (37). In this study, we found that GMFG directly interacted with the SNARE protein STX4 and its binding protein STXBP4 in monocytes, indicating that GMFG-mediated β1-integrin recycling might occur in cooperation with these SNARE proteins. Indeed, it has been reported that STXBP4 is involved in the insulin-stimulated trafficking of the glucose transporter GLUT4 vesicle to the cell surface by regulation of membrane fusion in muscle cells and adipocytes (21, 57). However, other reports suggest that STXBP4 plays an inhibitory role in SNARE-dependent membrane fusion with the plasma membrane (58, 59). Recently, further studies have shown that phosphorylation of STXBP4 is required for GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane in response to insulin stimulation in both adipocytes and podocytes, indicating that the phosphorylation site of STXBP4 might be important for membrane fusion (22, 60). These results, combined with our finding that knockdown of STXBP4, but not STX4, inhibits the chemotactic migration and recycling of β1-integrin in monocytes, suggest that GMFG-facilitated recycling of β1-integrin might coordinate with STXBP4 to modulate fusion of β1-integrin-containing vesicles to the leading edge membrane during monocyte migration. However, it remains to be determined whether GMFG-mediated recycling of β1-integrin occurs in cooperation with other components of the trafficking machinery (e.g. SNX17, Ras small GTPase, or Arf6) or promotes recycling of other β-integrins to the cell surface membrane (61, 62). Therefore, further detailed investigation is needed to determine how GMFG functions in β1-integrin recycling.

In summary, our findings suggest that GMFG interacts with the SNARE protein STXBP4 and that together they are key regulators in β1-integrin recycling and degradation that direct the intracellular trafficking of internalized β1-integrin to recycle back to the plasma membrane rather than to the lysosomes for degradation. Hence, GMFG may play an important role in maintaining appropriate levels of β1-integrin and efficient monocyte migration and adhesion.

Author Contributions

W. A. and G. P. R. designed the research; W. A., L. L., J. Z., and C. K. performed the research; K. C. contributed vital new reagents; W. A. analyzed the data; W. A and G. P. R. wrote the manuscript; and all authors checked the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Daniela A. Malide (NHLBI, National Institutes of Health, Light Microscopy Core Facility) for skillful help with immunofluorescence confocal microscope imaging.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIDDK, National Institutes of Health. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Movies S1–S8.

- GMFG

- glia maturation factor-γ

- fMLP

- formyl-Met-Leu-Phe

- FN

- fibronectin

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution.

References

- 1. Ley K., Laudanna C., Cybulsky M. I., and Nourshargh S. (2007) Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wong C. H., Heit B., and Kubes P. (2010) Molecular regulators of leucocyte chemotaxis during inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 86, 183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Herter J., and Zarbock A. (2013) Integrin regulation during leukocyte recruitment. J. Immunol. 190, 4451–4457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steeber D. A., and Tedder T. F. (2000) Adhesion molecule cascades direct lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte migration during inflammation. Immunol. Res. 22, 299–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chuluyan H. E., Schall T. J., Yoshimura T., and Issekutz A. C. (1995) IL-1 activation of endothelium supports VLA-4 (CD49d/CD29)-mediated monocyte transendothelial migration to C5a, MIP-1α, RANTES, and PAF but inhibits migration to MCP-1: a regulatory role for endothelium-derived MCP-1. J. Leukoc. Biol. 58, 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meerschaert J., and Furie M. B. (1995) The adhesion molecules used by monocytes for migration across endothelium include CD11a/CD18, CD11b/CD18, and VLA-4 on monocytes and ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and other ligands on endothelium. J. Immunol. 154, 4099–4112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luscinskas F. W., Kansas G. S., Ding H., Pizcueta P., Schleiffenbaum B. E., Tedder T. F., and Gimbrone M. A. Jr. (1994) Monocyte rolling, arrest and spreading on IL-4-activated vascular endothelium under flow is mediated via sequential action of L-selectin, β1-integrins, and β2-integrins. J. Cell Biol. 125, 1417–1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Margadant C., Monsuur H. N., Norman J. C., and Sonnenberg A. (2011) Mechanisms of integrin activation and trafficking. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caswell P. T., Vadrevu S., and Norman J. C. (2009) Integrins: masters and slaves of endocytic transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 843–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thapa N., Sun Y., Schramp M., Choi S., Ling K., and Anderson R. A. (2012) Phosphoinositide signaling regulates the exocyst complex and polarized integrin trafficking in directionally migrating cells. Dev. Cell 22, 116–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Franceschi N., Hamidi H., Alanko J., Sahgal P., and Ivaska J. (2015) Integrin traffic: the update. J. Cell Sci. 128, 839–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Day P., Riggs K. A., Hasan N., Corbin D., Humphrey D., and Hu C. (2011) Syntaxins 3 and 4 mediate vesicular trafficking of α5β1 and α3β1 integrins and cancer cell migration. Int. J. Oncol. 39, 863–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rothman J. E. (1994) Mechanisms of intracellular protein transport. Nature 372, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jahn R., Lang T., and Südhof T. C. (2003) Membrane fusion. Cell 112, 519–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonifacino J. S., and Glick B. S. (2004) The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell 116, 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McNew J. A., Parlati F., Fukuda R., Johnston R. J., Paz K., Paumet F., Söllner T. H., and Rothman J. E. (2000) Compartmental specificity of cellular membrane fusion encoded in SNARE proteins. Nature 407, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Riggs K. A., Hasan N., Humphrey D., Raleigh C., Nevitt C., Corbin D., and Hu C. (2012) Regulation of integrin endocytic recycling and chemotactic cell migration by syntaxin 6 and VAMP3 interaction. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3827–3839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tiwari A., Jung J. J., Inamdar S. M., Brown C. O., Goel A., and Choudhury A. (2011) Endothelial cell migration on fibronectin is regulated by syntaxin 6-mediated α5β1 integrin recycling. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36749–36761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Veale K. J., Offenhäuser C., Lei N., Stanley A. C., Stow J. L., and Murray R. Z. (2011) VAMP3 regulates podosome organisation in macrophages and together with Stx4/SNAP23 mediates adhesion, cell spreading and persistent migration. Exp. Cell Res. 317, 1817–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kawaguchi T., Tamori Y., Kanda H., Yoshikawa M., Tateya S., Nishino N., and Kasuga M. (2010) The t-SNAREs syntaxin4 and SNAP23 but not v-SNARE VAMP2 are indispensable to tether GLUT4 vesicles at the plasma membrane in adipocyte. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 1336–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Min J., Okada S., Kanzaki M., Elmendorf J. S., Coker K. J., Ceresa B. P., Syu L. J., Noda Y., Saltiel A. R., and Pessin J. E. (1999) Synip: a novel insulin-regulated syntaxin 4-binding protein mediating GLUT4 translocation in adipocytes. Mol. Cell 3, 751–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Okada S., Ohshima K., Uehara Y., Shimizu H., Hashimoto K., Yamada M., and Mori M. (2007) Synip phosphorylation is required for insulin-stimulated Glut4 translocation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 356, 102–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ikeda K., Kundu R. K., Ikeda S., Kobara M., Matsubara H., and Quertermous T. (2006) Glia maturation factor-γ is preferentially expressed in microvascular endothelial and inflammatory cells and modulates actin cytoskeleton reorganization. Circ. Res. 99, 424–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shi Y., Chen L., Liotta L. A., Wan H. H., and Rodgers G. P. (2006) Glia maturation factor γ (GMFG): a cytokine-responsive protein during hematopoietic lineage development and its functional genomics analysis. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 4, 145–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aerbajinai W., Liu L., Chin K., Zhu J., Parent C. A., and Rodgers G. P. (2011) Glia maturation factor-γ mediates neutrophil chemotaxis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90, 529–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lippert D. N., and Wilkins J. A. (2012) Glia maturation factor γ regulates the migration and adherence of human T lymphocytes. BMC Immunol. 13, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gandhi M., Smith B. A., Bovellan M., Paavilainen V., Daugherty-Clarke K., Gelles J., Lappalainen P., and Goode B. L. (2010) GMF is a cofilin homolog that binds Arp2/3 complex to stimulate filament debranching and inhibit actin nucleation. Curr. Biol. 20, 861–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ydenberg C. A., Padrick S. B., Sweeney M. O., Gandhi M., Sokolova O., and Goode B. L. (2013) GMF severs actin-Arp2/3 complex branch junctions by a cofilin-like mechanism. Curr. Biol. 23, 1037–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boczkowska M., Rebowski G., and Dominguez R. (2013) Glia maturation factor (GMF) interacts with Arp2/3 complex in a nucleotide state-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 25683–25688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pollard T. D., and Cooper J. A. (2009) Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. Science 326, 1208–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Firat-Karalar E. N., and Welch M. D. (2011) New mechanisms and functions of actin nucleation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 4–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu L., Das S., Losert W., and Parent C. A. (2010) mTORC2 regulates neutrophil chemotaxis in a cAMP- and RhoA-dependent fashion. Dev. Cell 19, 845–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cera M. R., Fabbri M., Molendini C., Corada M., Orsenigo F., Rehberg M., Reichel C. A., Krombach F., Pardi R., and Dejana E. (2009) JAM-A promotes neutrophil chemotaxis by controlling integrin internalization and recycling. J. Cell Sci. 122, 268–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones M. C., Caswell P. T., and Norman J. C. (2006) Endocytic recycling pathways: emerging regulators of cell migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arjonen A., Alanko J., Veltel S., and Ivaska J. (2012) Distinct recycling of active and inactive β1 integrins. Traffic 13, 610–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Caswell P. T., and Norman J. C. (2006) Integrin trafficking and the control of cell migration. Traffic 7, 14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen Y. A., and Scheller R. H. (2001) SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 98–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ridley A. J., Schwartz M. A., Burridge K., Firtel R. A., Ginsberg M. H., Borisy G., Parsons J. T., and Horwitz A. R. (2003) Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302, 1704–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pellinen T., and Ivaska J. (2006) Integrin traffic. J. Cell Sci. 119, 3723–3731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lawson M. A., and Maxfield F. R. (1995) Ca2+- and calcineurin-dependent recycling of an integrin to the front of migrating neutrophils. Nature 377, 75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Veale K. J., Offenhäuser C., and Murray R. Z. (2011) The role of the recycling endosome in regulating lamellipodia formation and macrophage migration. Commun. Integr. Biol. 4, 44–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mellman I. (2000) Quo vadis: polarized membrane recycling in motility and phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 149, 529–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chang F. S., Stefan C. J., and Blumer K. J. (2003) A WASp homolog powers actin polymerization-dependent motility of endosomes in vivo. Curr. Biol. 13, 455–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tanabe K., Ohashi E., Henmi Y., and Takei K. (2011) Receptor sorting and actin dynamics at early endosomes. Commun. Integr. Biol. 4, 742–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morel E., Parton R. G., and Gruenberg J. (2009) Annexin A2-dependent polymerization of actin mediates endosome biogenesis. Dev. Cell 16, 445–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rankin C. R., Hilgarth R. S., Leoni G., Kwon M., Den Beste K. A., Parkos C. A., and Nusrat A. (2013) Annexin A2 regulates β1 integrin internalization and intestinal epithelial cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 15229–15239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Derivery E., Sousa C., Gautier J. J., Lombard B., Loew D., and Gautreau A. (2009) The Arp2/3 activator WASH controls the fission of endosomes through a large multiprotein complex. Dev. Cell 17, 712–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]