Abstract

Understanding gas migration pathways is critical to unraveling structure-function relationships in enzymes that process gaseous substrates such as O2, H2, and N2. This work investigates the role of a defined pathway for O2 in regulating the peroxidation of linoleic acid by soybean lipoxygenase 1. Computational and mutagenesis studies provide strong support for a dominant delivery channel that shuttles molecular oxygen to a specific region of the active site, thereby ensuring the regio- and stereospecificity of product. Analysis of reaction kinetics and product distribution in channel mutants also reveals a plasticity to the gas migration pathway. The findings show that a single site mutation (I553W) limits oxygen accessibility to the active site, greatly increasing the fraction of substrate that reacts with oxygen free in solution. They also show how a neighboring site mutation (L496W) can result in a redirection of oxygen toward an alternate position of the substrate, changing the regio- and stereospecificity of peroxidation. The present data indicate that modest changes in a protein scaffold may modulate the access of small gaseous molecules to enzyme-bound substrates.

Keywords: catalysis, enzyme mechanism, enzyme mutation, kinetics, protein structure, lipoxygenase, oxygen channel, regio- and stereospecificity

Introduction

Structure-function studies of enzymes have moved beyond an exclusive focus on active site protein side chains, with the growing recognition that distal residues can have a significant impact on catalytic bond cleavage events (1, 2). Topological features within the protein matrix, such as cavities and channels, can also play key roles in the flux of biomolecules. For proteins with gaseous substrates, e.g. O2, H2, N2, and NH3, specific channels have been proposed either to transport reactive intermediates between active sites within a multifunctional enzyme (3) or to guide these small molecules from the solvent to the active site. The likely importance of the latter is relevant to a wide range of enzymes that includes oxidases, monooxygenases, nitrogenases, and hydrogenases (4–17). The involvement of functionally evolved gas channels represents a significant departure from earlier held views in which random, transient fluctuations within a protein were proposed to facilitate the delivery of gaseous substrates to their site of binding and/or reactivity.

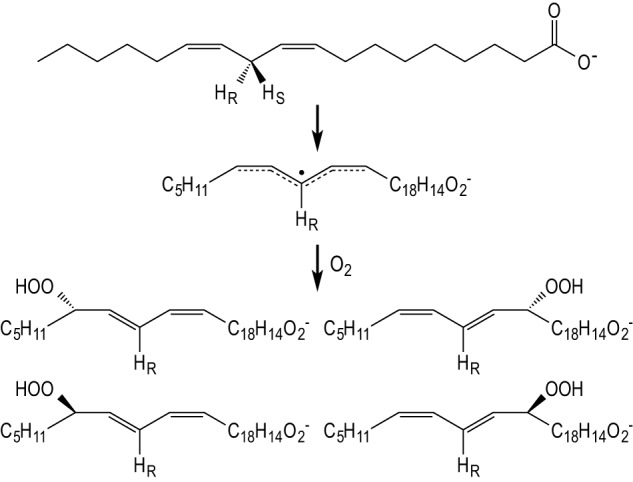

Studies of lipoxygenases have aided in this shift in perception, given their requirement to capture O2 via highly regio- and stereospecific pathways. As illustrated in Fig. 1 for the reaction catalyzed by soybean lipoxygenase-1 (SLO-1),3 the delocalized nature of the free radical intermediate generated from the preferred substrate linoleic acid (LA) predicts that four unique products will be produced in equal amounts in solution. By contrast, native SLO-1 produces the 13S-hydroperoxide product (13S-HPOD) in greater than 90% yield for reaction of WT enzyme under optimal conditions. The precise mechanism by which SLO-1, as well as other lipoxygenases, maintain the regio- and stereospecificity of product peroxidation has engendered a variety of proposals that include: (i) an alteration in substrate binding (from head to tail first) as a means of reversing the enantiomeric specificity of O2 addition to a fixed carbon center; (ii) the interchange of a single active site residue between Gly and Ala to alter the position (but not the face) of O2 attack; and (iii) a directed movement of O2 through the protein matrix toward a spatially defined position of substrate that is capable of simultaneously controlling both the position and face of O2 attack on a substrate-derived free radical intermediate (4, 16, 18).

FIGURE 1.

Simplified chemical mechanism of SLO illustrating two half-reactions in which the C–H bond is cleaved at carbon 11, and O2 is inserted at carbon 13. The primary 13S-HPOD product is shown as the upper left hand product structure, whereas reaction in solution is predicted to produce a mixture of two 13-HPOD and two 9-HPOD products.

Although all three of the above factors may play a role in the evolution of lipoxygenases that catalyze the formation of stereo- and regiochemically distinct hydroperoxides, there remains the generic question of how each enzyme manages a transit of O2 from bulk solvent toward the reactive carbon of buried substrate. The x-ray structure of SLO-1 is quite informative in this regard, implicating a putative gas channel that appears “crimped” in its middle at the residue Ile553 (18). Earlier support for the involvement of this channel came from the generation of an I553F mutant enzyme that showed a reduction in rate for the O2-dependent portion of the SLO-1 reaction accompanied by only a modest impact on the initial C–H abstraction step and the position/stereochemistry of substrate peroxidation (3). The reaction mechanism invoked for I553F involves protein breathing modes capable of relieving a mutation-induced “steric impasse” toward O2 (19). In the present study, we have greatly extended this line of inquiry via the incorporation of a range of amino acid side chains into four targeted channel positions. The new findings both corroborate a role for a discrete gas channel in SLO-1 while revealing conditions capable of altering the pathway for O2 delivery to the active site of lipoxygenases.

Experimental Procedures

Identifying Pathways for O2 Migration

The CAVER 3.0 software tool was employed to identify all possible routes from the active site in SLO to the solvent, based on the x-ray coordinates of the enzyme and a radius for gas migration (18, 20). To approximate the location of the active site, starting point coordinates within SLO were computed as the spatial averages of the coordinates of the catalytic iron atom and active site residue Leu546. A minimum bottleneck radius of 0.9 Å was specified. The results were visualized in the molecular visualization program VMD to facilitate comparison to implicit ligand sampling (ILS) results (21).

Mapping O2 Affinity in SLO

The LEaP module of the Amber 11 software package was used to generate a fully solvated model of SLO based on the x-ray coordinates of the enzyme (18, 22). In the crystal structure, the nonheme iron is in the ferrous state, complexed by the side chains of His499, His504, His690, and Asn694 in addition to the carboxylate of Ile839 and a water molecule (18). Topology and force field parameters for the bound water in the active site were adapted from a TIP3P model, and parameters for the iron ligand were adapted from those published for a six-coordinate iron in a heme-containing protein (23, 24). Amber FF99 force field parameters were employed for the protein, as in previous SLO simulations (25–27). The SLO structure was solvated in a truncated octahedral box of TIP3P waters, and the overall charge of the system was neutralized by the addition of 11 peripheral sodium cations (26). After equilibration, a 10-ns molecular dynamics simulation of the SLO system was performed using an isothermic-isobaric ensemble, as is required for ILS analysis (28).

The ILS tool was applied to the molecular dynamics simulation of SLO to assess regions favorable for oxygen migration within the enzyme. The ILS technique allows for the generation of a three-dimensional map of the Gibbs free energy cost, or ΔGs(O2), associated with transferring an oxygen molecule from a vacuum to a particular position inside the protein (28). ΔGs(O2) was evaluated for every 1 Å3 volume element throughout the SLO system. Within each of these elements, oxygen was placed in 20 different rotational orientations at each of 27 different positions on a 3 × 3 × 3 grid. Five thousand protein conformations were sampled from the 10-ns trajectory. A three-dimensional free energy map was generated describing the distribution of oxygen throughout SLO. Regions of the enzyme likely to be occupied by oxygen were identified by drawing isoenergy surfaces—that is, plotting all points in a protein for which the ΔGs(O2) is below a certain value. The results were visualized in VMD, the molecular visualization program in which the ILS method is realized (21).

Site-directed Mutagenesis and Protein Expression and Purification

Seven SLO mutants were generated through site-directed mutagenesis according to the QuikChange II protocol (Agilent Technologies). HPLC-purified primers were purchased from Eurofins MWG Operon, and sequencing was performed by UC Berkeley Sequencing Facility. The V564F lipoxygenase mutant was expressed and purified using the SLO pT7-7 plasmid in Escherichia coli, as described previously (29, 31). WT SLO and all other mutants were expressed and purified as His tag fusion proteins using the SLO pET-30Xa/LIC plasmid, acquired from Professor Betty Gaffney at Florida State University. These enzymes were expressed and purified as described previously, with several modifications (31). His-tagged SLO was eluted with wash buffer containing 250 mm imidazole and dialyzed overnight (4 °C) into 20 mm Bis-Tris (pH 6.6) buffer. The dialyzed eluate from nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography was concentrated and injected onto an FPLC system with a 6-ml UNO S6 column (Bio-Rad) for separation by cation exchange chromatography. A salt gradient for protein elution was run from 0.0 to 0.5 m NaCl in 20 mm Bis-Tris (pH 6.6) buffer. SLO activity was assayed in fractions by monitoring the formation of HPOD at 234 nm upon the addition of 5 μl of a column fraction to 245 μl of 100 μm linoleic acid in 0.1 m borate (pH 9.0). Fractions containing SLO activity were combined, dialyzed into 0.1 m borate (pH 9.0), concentrated, and stored at −80 °C.

Enzyme Kinetics

Oxygen electrode and UV kinetic assays were performed for WT SLO and each mutant lipoxygenase as described previously (19, 29, 31). Oxygen concentration was varied from 30 to 1365 μm. LA concentration was varied from 2 to 80 μm. All kinetic assays were performed at 20 °C and in 0.1 m borate (pH 9.0). Reported estimates of kcat are derived from oxygen electrode studies rather than UV kinetic data, allowing extrapolation rather than correction for saturating O2.

Enzyme Regio- and Stereospecificity

The reactions were incubated at 20 °C in 0.1 m borate (pH 9.0) and 100 μm LA for 5 h after initiation with enzyme. The reactions at elevated and depressed O2 concentrations were performed using a Clark-type electrode from Yellow Springs Inc. and a YSI-5300 biological oxygen monitor. The reaction mixtures were quenched at pH 4 (glacial acetic acid) and extracted into dichloromethane. Reaction products were taken to dryness under a stream of N2 and stored at −80 °C until HPLC analysis. Reaction products were injected onto a reverse phase HPLC system with a Luna C18 5-μm column (0.46 × 25 cm; Phenomenex). An isocratic solvent system of 78% methanol and 21.9% water with 0.1% acetic acid was employed to elute HPOD. A flow rate of 0.9 ml/min was used. HPOD was collected, taken to dryness under N2, and reduced via incubation for >1 h with a solution of 1.9 mm triphenylphosphine in methanol. The hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (HODE) generated was taken to dryness under N2 and stored at −80 °C until chiral phase HPLC analysis.

HODE was injected onto a chiral phase HPLC system with a Chiralcel OD-3 column (0.46 × 25 cm; Chiral Technologies, Inc.). An isocratic solvent system of 1.55% isopropanol, 0.3% acetic acid, and 98.2% hexanes was employed to separate the 13S, 13R, 9S, and 9R isomers. A flow rate of 2 ml/min was used. Assignment of the four HODE isomeric peaks was accomplished using standards of 13S-, 13R-, 9S-, and 9R-HODE acquired from Cayman Chemical.

Results

Computational Prediction of the Preferred Route(s) for Oxygen Delivery to the SLO-1 Active Site

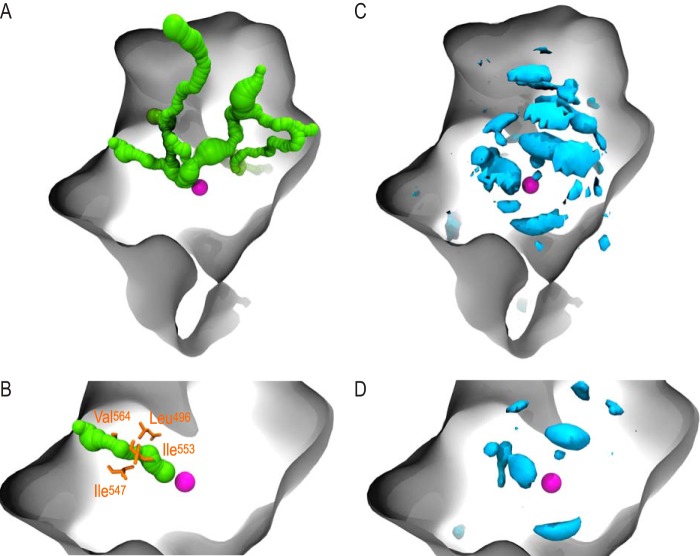

Two parallel computational techniques, CAVER and implicit ligand sampling, were employed to probe gas migration within SLO-1. The CAVER 3.0 software tool was used to identify pathways linking the SLO active site to the solvent. Assigning a bottleneck radius of 0.9 Å for passage of O2 through the protein, eight routes were detected (Fig. 2A) with the length, average radius, and minimum radius, summarized in Table 1. Pathways were also ranked from most favorable (A) to least favorable (H) by CAVER, based on a throughput parameter that takes into account channel length as well as width. Channel A (Fig. 2B) was identified by CAVER as the most favorable route for oxygen to travel from the solvent to the active site. This channel exhibits the highest throughput (0.4) and largest bottleneck radius (1.1 Å), as well as the second largest mean radius and second shortest total length. Four residues were identified within 1.5 Å of the bottleneck of channel A: Ile553, Ile547, Leu496, and Val564 (Fig. 2B). In short, our analysis indicates that although multiple pathways link the buried SLO active site and solvent, channel A is identified as the preferred route for oxygen delivery to the site of catalysis.

FIGURE 2.

A and B, computational analysis of O2 transport in SLO using CAVER. The surface of SLO is depicted in gray, and the catalytic iron, a hallmark of the active site, is represented as a magenta sphere. A, eight channels (green) were detected extending from the buried active site in SLO to the exterior of the protein. B, channel A (green) was identified as the most favorable route from the active site to the solvent according to a throughput metric computed by CAVER that favors short, wide channels. Residues within 1.5 Å of the bottleneck of channel A are depicted in orange and are listed here, sorted from closest to the iron center: Ile553, Ile547, Leu496, and Val564. C and D, computational analysis of O2 transport in SLO using ILS. SLO is represented by a gray surface, and the catalytic iron atom is depicted as a magenta sphere. C, the −0.5 kT isoenergy surface (cyan) highlights multiple, preferred pockets for oxygen to inhabit throughout the SLO protein matrix. D, the −2.5 kT isoenergy surface (cyan) imposes a more stringent requirement than the −0.5 kT surface, including only the most favorable regions for oxygen migration in the protein matrix. Note the pocket to the left of the catalytic iron, which is located closest to the active site.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of eight channels detected and ranked by CAVER

Length, mean radius, and bottleneck radius were computed by the program in addition to a throughput parameter that reflects the overall competency of each channel. Based on this throughput parameter, each channel was ranked by CAVER, with A representing the most favorable tunnel and H representing the least favorable path. Pathways with small lengths and large radii (e.g. A) were preferred to longer, narrower tunnels (e.g. H).

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (Å) | 21 | 20 | 25 | 41 | 50 | 44 | 109 | 133 |

| Mean radius (Å) | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Bottleneck radius (Å) | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Throughput | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.002 | 0.0003 |

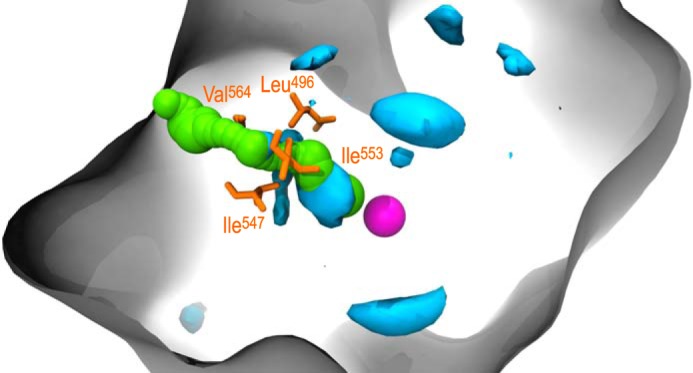

In parallel with the geometric algorithm employed by CAVER, ILS simulations were performed to detect energetically favorable regions for oxygen to occupy within SLO. This technique infers gas migration pathways by generating a three-dimensional map of the Gibbs free energy cost associated with placing an oxygen molecule anywhere in the protein. Lower free energy values are associated with a greater probability of finding oxygen. Regions of SLO likely to be occupied by oxygen were mapped by drawing free energy isosurfaces at −0.5 kT (Fig. 2C) and −2.5 kT (Fig. 2D). Together, these energy maps indicate that although pockets favorable for the gas exist throughout SLO, dioxygen tends to concentrate near the active site. Interestingly, the largest pocket outlined by the −2.5 kT isosurface directly overlaps with the top-ranked pathway identified by CAVER, channel A (Fig. 3). This pocket, which is adjacent to the active site, is also located in close proximity to the four bottleneck residues of channel A. Together, energetic and geometric insights from ILS and CAVER, respectively, point to a single pathway for oxygen delivery and implicate four residues in modulating oxygen access to the active site.

FIGURE 3.

SLO depicted with the −2. 5 kT isoenergy surface computed by ILS, as well as channel A and its bottleneck residues identified by CAVER. The largest pocket outlined by the −2.5 kT isoenergy surface (cyan) directly overlaps with channel A (green), the top-ranked channel detected by CAVER. This region is also in close proximity to the bottleneck residues identified by CAVER (orange), highlighting the accordance of these two techniques. Overlap of the −2.5 kT isoenergy surface with other channels detected by CAVER (B–H) is comparatively small, consistent with channel A representing the biologically relevant pathway.

Introducing Larger Amino Acid Side Chains into Channel A Disrupts Oxygen Trafficking, as Evidenced by Altered Kinetic Parameters for O2

To assess the functional role of channel A, steric bulk was introduced at bottleneck residues 553, 547, 496, and 564 via site-directed mutagenesis. The impact of mutations on oxygen delivery was assessed by determining kcat, Km(O2), Km(LA), and the respective kcat/Km parameters (Table 2). Focusing on the insertion of Trp at the four positions, the change in kcat/Km(LA) is negligible for positions 547 and 564 in relation to WT. By contrast, Trp at positions 553 and 496 leads to quite significant changes in kcat/Km(LA), with values that are only 10−3 to 10−2 of WT. In the case of kcat/Km(O2), all of the selected mutants indicate rate reductions, ranging from 2-fold (V564W) to ∼104-fold (I553W). This behavior is mirrored in Km values of 132–744 μm O2 compared with 38 μm for WT SLO. A key issue is the degree to which an increase in side chain size decreases kcat/Km(O2) to a greater extent than kcat/Km(LA). This feature is evaluated in the final column of Table 2, highlighting the largest impact of Trp occurring at positions 553 and 496 on O2. In support of a straightforward analysis of the observed Km(O2) and kcat/Km(O2) parameters, we note the absence of an elevation of the Km(LA) for any of the variants interrogated here. All previous studies of mutants of SLO-1 (cf. Refs. 29, 30, and 32) support an unchanged rate determining step that is controlled by C–H cleavage, implying that Km ≅ Kd for both WT and mutant variants. The consequences of Trp at positions 553 and 496 become even more apparent following analysis of the product distribution among the four possible HPODs (cf. Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic characterization of SLO mutants

The experiments were conducted at 20 °C, pH 9. kcat is at saturating concentrations of both LA and O2, whereas the kcat/Km indicated is at saturation with regard to the alternate substrate.

| SLO | kcat |

Km |

kcat/Km |

Impact of mutation on kcat/Kma | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA | O2 | LA | O2 | |||

| s−1 | μm | μm | s−1 μm−1 | s−1 μm−1 | ||

| WTb | 211 ± 9 (230 ± 15) | 20 ± 2 (18 ± 3) | 38 ± 5 (31 ± 3) | 11 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | |

| I553Fc | 102 ± 8 | 19 ± 4 | 142 ± 58 | 5 ± 1 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 3.8 |

| I553W | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 25 ± 5 | 744 ± 142 | 0.016 ± 0.004 | 0.0005 ± 0.0001 | 18 |

| I547F | 66 ± 5 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 44 ± 11 | 22 ± 3 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 8 |

| I47W | 44 ± 2 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 50 ± 7 | 9 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 5.5 |

| L496F | 44 ± 3 | 5 ± 1 | 132 ± 26 | 9 ± 2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 16 |

| L496W | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 11.0 ± 0.8 | 171 ± 33 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 9.1 |

| V564F | 60 ± 1 | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 46 ± 5 | 10 ± 1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 4.2 |

| V564W | 99 ± 5 | 8.0 ± 0.7 | 32 ± 6 | 12 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 2.2 |

a The impact of mutation for the kcat/Km for either LA or O2 was first calculated. The ratio of the mutational impairment on kcat/Km for O2 relative to that for LA is reported in the final column.

b The numbers in parentheses indicate the measured parameters with non-His-tagged protein. As a frame of reference, native SLO-1, isolated from soybeans, gave kcat ≅ 150 s−1, Km(LA) ≅ 40 μm, and Km(O2) ≅ 30 μm under the same reaction conditions (37).

c The data for I553F are from Ref. 19.

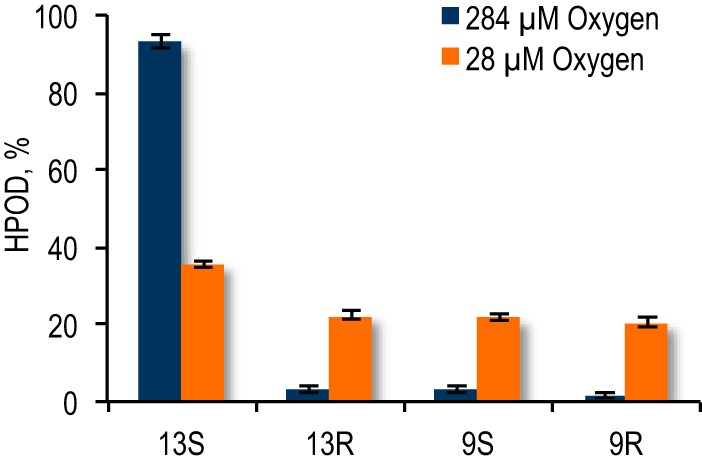

Diminishing O2 Availability at the Active Site of WT SLO-1 Disrupts the Regio- and Stereospecificity of Product

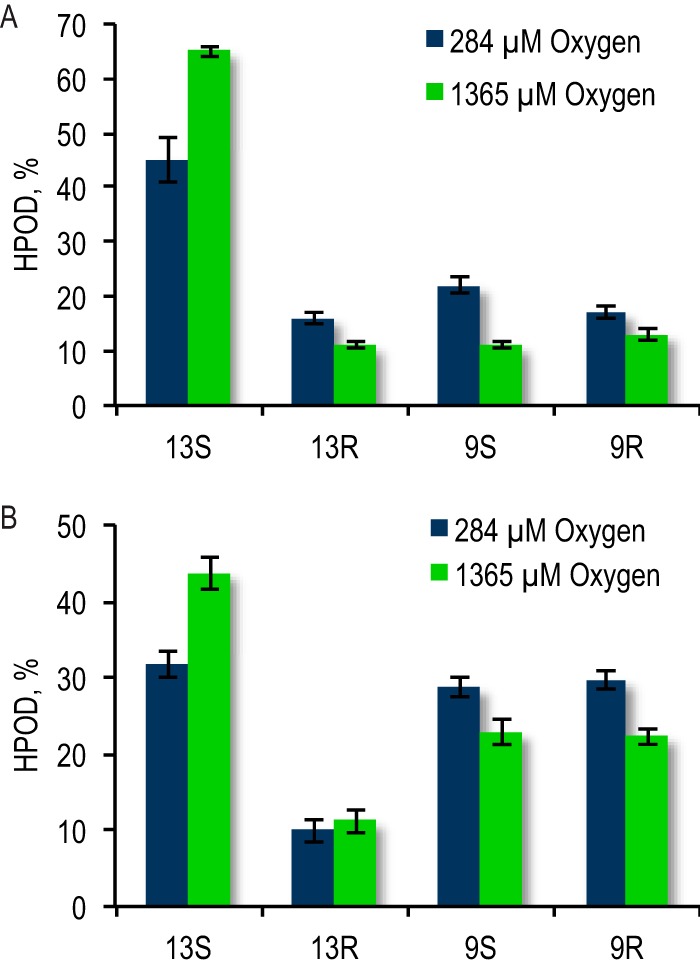

In addition to kinetic parameters, the regio- and stereospecificity of the SLO-catalyzed reaction provides a measure of oxygen availability at the active site. Significant loss of regiospecificity, for example, has been documented in the reaction of LA with SLO under low oxygen conditions, where the ratio of 13 HPOD to 9 HPOD approaches 1:1 (33). Diminished oxygen availability is thought to result in increased dissociation of the linoleyl radical intermediate into solution, where it can react indiscriminately with oxygen. Our investigation of the SLO-catalyzed reaction at low oxygen confirms previous findings with respect to regiospecificity and furthermore discerns the proportion of 13S-, 13R-, 9R-, and 9S-HPOD produced at low O2 (Fig. 4). At ambient oxygen, 13R-, 9S-, and 9R-HPOD are present in small amounts and account in total for <10% of HPOD produced. At 28 μm O2, by contrast, a substantial amount of 13R-, 9S-, and 9R-HPOD is generated. The alternate isomers are produced in approximately equivalent amounts, each accounting for ∼21% of total HPOD produced. These results support the hypothesis that reduced oxygen availability leads to nonspecific oxygen insertion during the peroxidation of LA by SLO and serve as controls for the impact of site-specific mutagenesis and altered oxygen tension on product distribution.

FIGURE 4.

Impact of diminished O2 on the regio- and stereospecificity of WT-SLO-1.

Introducing Steric Restriction into Channel A Disrupts the Regio- and Stereospecificity of Product HPODs

The impact of mutation on SLO-1 regio- and stereospecificity provides one important probe of the disruption of oxygen trafficking. This is seen to be most dramatic for three SLO mutants, I553W, L496F, and L496W (Table 3). In accordance with the kinetic data (Table 2), analysis of product distribution implicates important roles for positions 553 and 496 in directing O2 from the solvent to the correct position and face within the substrate-derived pentadienyl radical.

TABLE 3.

Regio- and stereospecificity of product formation with mutant forms of SLO-1

The experiments were performed under the conditions of pH 9, 20 °C, and ambient O2 concentration (284 μm). The errors range from 6 to 18% of the stated values.

| SLO | 13S HPOD | 13R HPOD | 9S HPOD | 9R HPOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | |

| WT | 93 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| I553Fa | 95 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| I553W | 45 | 16 | 22 | 17 |

| I547F | 93 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| I547W | 93 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| L496F | 63 | 9 | 14 | 14 |

| L496W | 32 | 10 | 29 | 30 |

| V564F | 89 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| V564W | 86 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

a Ref. 4.

Replacement of Ile553, which is fully conserved in all soybean lipoxygenases, by Trp and reaction with LA produces 45% 13S-HPOD, whereas the WT enzyme generates 93% 13S-HPOD. A substantial amount of 13R-, 9S-, and 9R-HPOD is thus produced with I553W. These isomers account for >50% of HPOD and, importantly, are seen to be generated in roughly equivalent amounts. The regio- and stereospecificity of the I553W mutant resembles that of the WT reaction at low O2, consistent with restricted oxygen availability and the resulting increased dissociation of the linoleyl radical to solution. This explanation is supported by the significantly elevated Km(O2) determined for this mutant (744 μm O2). We note that introducing phenylalanine at position 553 does not disrupt regio- and stereospecificity in the same way as tryptophan. Despite exhibiting an elevated Km(O2), the I553F mutant produces >90% 13S-HPOD. The introduction of phenylalanine at position 553 reduces the rate at which O2 reaches the substrate derived radical (19) while leaving the regio- and stereospecificity of product formation intact. We propose that the key factor in determining the fidelity of product formation is the ratio of rate constants for trapping of the bound pentadienyl intermediate by O2 versus its release from enzyme. The insertion of Trp at position 553 has clearly tipped the balance toward a solution-based reaction of substrate with O2, in a manner resembling the impact of reduced O2 concentration on the product distribution of WT enzyme.

Regio- and stereospecificity is also dramatically disrupted in the reaction of both Leu496 mutants with LA. Reaction with the phenylalanine and tryptophan mutants produces 63 and 31% 13S-HPOD that is accompanied by a substantial amount of 13R-, 9S-, and 9R-HPOD; together, these alternate isomers account for 37 and 69% of HPOD produced in reactions with L496F and L496W (Table 3). It is significant that the 13R, 9S, and 9R isomers are produced in unequal amounts, contrasting with the behaviors of WT SLO at low oxygen and the I553W mutant. This is particularly apparent for the L496W mutant, where the 9S and 9R isomers each account for 29 and 30% of HPOD produced compared with 10% for the 13R isomer. The disparity is more subtle in the case of L496F, where the 9S and 9R isomers account for 14% of HPOD produced compared with 9% for 13R-HPOD. We conclude that the altered regio- and stereospecificity of the Leu496 mutant reactions cannot be simply explained by a restricted availability of O2 at the active site that results in increased loss of the substrate radical to solvent. Rather, the elevated amount of 9R and 9S-HPOD suggests a gain of function for the Leu496 mutations, i.e. the opening up of an alternate route for gas migration that allows O2 to access carbon 9 of the substrate radical. We note that earlier studies (31) have discussed a changeover from the production of 13S- to 13R-HPOD products in the event of a “reverse binding” of substrate, under conditions where the fatty acid carboxylate of substrate becomes protonated and can orient itself toward the protein interior. Whereas this phenomenon may account for behaviors at pH 7, it is an unlikely explanation for the behavior reported herein at pH 9. With the expectation that reverse binding will not be sensitive to increased O2 levels and to further test out the hypothesis that the behavior of the Ile553 and Leu496 variants is due to perturbations in a gas channel, we examined the impacts of O2 concentration on product distributions with I553W and L496W.

Increased Levels of [O2] Partially Rescue WT Regio- and Stereospecificity in Reactions of I553W and L496W

Reaction of both the I553W and L496W mutants was characterized at elevated O2 concentration (1365 μm O2). As shown in Fig. 5, increasing [O2] from 284 to 1365 μm reduces the amount of 13R, 9S, and 9R isomers generated by the I553W mutant from 55 to 35% of total HPOD produced. The amount of 13S-HPOD generated by the I553W reaction similarly increases from 45% at ambient O2 to 65% at 1365 μm O2. Increased O2 can be concluded to partially restore the regio- and stereospecificity of this mutant reaction, indicating that additional O2 compensates for impaired oxygen delivery in the mutant.

FIGURE 5.

Impact of increasing O2 concentration on the product distribution for reaction of I553W (A) and L496W (B) SLO with LA.

Elevated O2 is also able to partially restore the regio- and stereospecificity of the L496W mutant reaction (Fig. 5), but not by uniformly decreasing the amount of 13R, 9S, and 9R isomers produced as seen for I553W. This observation indicates that increasing [O2] has an impact that goes beyond simply increasing oxygen availability in relation to radical dissociation, as observed for I553W at high O2. As noted earlier, a decrease in radical dissociation would affect the formation of the 13R, 9S, and 9R product isomers equally. In contrast, elevated [O2] in L496W influences the partitioning of O2 between oxygen transport pathways, reducing the reaction at carbon 9 and increasing product formed via the pathway leading to a reaction at carbon 13. This result strongly supports the conclusion of a higher barrier for O2 reactivity through the normal channel (that leads to carbon 13) than for the newly introduced channel (leading to carbon 9) in L496W.

Discussion

Enzymes are complex systems that contain a variety of pockets, clefts, and channels throughout the protein matrix. These internal structural features can play an essential role in tuning enzyme function by modulating the flux of small molecules within the protein. For example, in flavo-monooxygenases and oxidases, oxygen delivery channels have been shown to guide oxygen from the solvent through preorganized protein cavities and direct it to the reacting C4a atom of the flavin cofactor (14, 34). In 12/15 lipoxygenase, a preferred route for oxygen travel has been identified that links the solvent and buried active site (6). Similarly, crystallographic and computational studies have also implicated oxygen access paths in cyclooxygenase, copper amine oxidase, cholesterol oxidase, and cytochrome c oxidase (8, 10, 11). The nuanced role of the protein matrix in influencing catalysis is not restricted to oxygen delivery. In hydrogenases, gas channels have been reported to selectively filter molecules such as oxygen and carbon monoxide to prevent inactivation at the active site (12, 17, 35). Recent investigation of heme nitric oxide/oxygen binding domains has suggested that tunnels not only direct gases to the heme iron but also modulate reversible gas binding (16). Importantly, our work is the first to directly implicate an oxygen channel in regulating regio- and stereospecificity by explicitly showing the production of alternate product isomers upon obstruction of the channel.

Lipoxygenases provide an ideal context in which to examine oxygen migration because product positional and stereochemistry, in addition to reaction kinetics, can report on oxygen targeting to the active site (36). In this work, the functional role of oxygen migration pathways was examined in SLO-1, the best studied member of the lipoxygenase family. Our computational and experimental findings support a role for a single delivery channel within SLO-1 that shuttles oxygen to the active site and ensures its regio- and stereospecific insertion during catalysis.

To examine oxygen trafficking within SLO-1 from both a structural and energetic perspective, two computational approaches were employed in parallel. ILS was used to identify regions favorable for oxygen travel throughout the protein whereas CAVER was employed to visualize pathways leading continuously from the active site to the exterior of the protein. Although these tools identify multiple pockets and pathways throughout the enzyme (Fig. 2), both converge on a single channel deemed most competent for oxygen delivery (Fig. 3) (20, 28) Interestingly, this channel is consistent with a cavity originally identified in the crystal structure of SLO and previously proposed as an O2 channel (4, 18, 32).

The functional role of this putative oxygen pathway was confirmed by introducing steric bulk at its bottleneck residues via site-directed mutagenesis. Introducing tryptophan at positions 553 and 496, in particular, dramatically disrupts oxygen trafficking to the active site, as evidenced by alterations in Michaelis constants and kcat/Km(O2) (Table 2) and reaction regio- and stereospecificity (Table 3) that, importantly, is dependent on the exogenous O2 level (Fig. 5). These observations point to a role for these residues as gatekeepers of a channel that shuttles oxygen to the active site.

Examining the regio- and stereospecificity of the I553W and L496W mutant reactions further reveals that introducing steric restriction at these positions disrupts oxygen trafficking in different ways. Tryptophan at position 553 diminishes oxygen availability at the SLO active site, effectively starving the enzyme for oxygen. Accordingly, the I553W reaction exhibits impaired regio- and stereospecificity similar to the reaction of WT SLO-1 at low oxygen (Table 3 and Fig. 4). This observation, coupled with the 20-fold increase in Km(O2) for the I553W mutant, is proposed to reflect limited oxygen availability at the active site and increased dissociation of the linoleyl free radical intermediate into solution that then undergoes reaction with O2 in a random manner. Consistent with this hypothesis, performing the I553W mutant reaction at high [O2] partially rescues the WT regio- and stereospecificity of the reaction (Fig. 5A).

Inserting tryptophan at position 496 has a more modest impact on oxygen availability at the active site, as evidenced by the changes in kcat/Km(O2) and Km(O2) (Table 2). The unique feature of L496W is its impact on regio- and stereospecificity, revealing the creation of an alternate pathway to the active site that grants oxygen access to carbon 9 of the substrate-derived radical. Accordingly, the proportion of 9S- and 9R-HPOD generated increases dramatically in the L496W reaction with LA compared with WT SLO, whereas the proportion of 13R-HPOD increases to a much smaller extent (Table 3). Based on implicit ligand sampling analysis (Fig. 2), multiple regions favorable for oxygen binding exist proximal to the active site. One or more of these regions may be rendered functional in the Leu496 mutant enzymes.

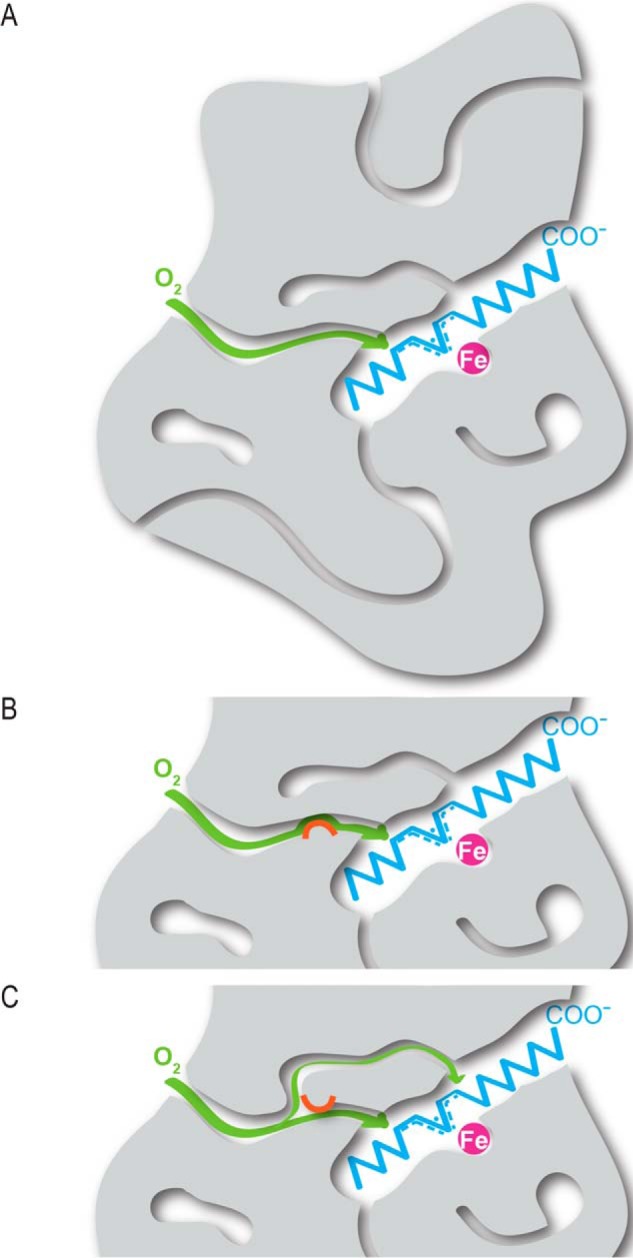

Consistent with our experimental and computational findings, a model for gas migration in WT SLO, as well as the I553W and L496W mutants, is depicted in Fig. 6. Although the SLO protein matrix contains a variety of tunnels and cavities, one pathway is primarily utilized for oxygen delivery to the active site of the WT enzyme. This oxygen delivery channel becomes impaired in the I553W mutation (Fig. 6B). Accordingly, O2 availability at the active site is diminished, as evidenced by the large decrease in kcat/Km(O2), an increased Michaelis constant for oxygen, and an increased proportion of equal levels of 13R-, 9S-, and 9R-HPOD produced in the peroxidation of LA that is partially reversed at elevated O2 concentration. The L496W mutation, by contrast, appears to unlock an alternate pathway to the active site (Fig. 6C), significantly increasing the proportion of 9S- and 9R-HPOD produced in the peroxidation of LA in an O2-dependent manner. These new findings, which extend previous evidence for a gas channel in SLO-1 (4), may provide insight into mechanisms for altered positions of oxygen delivery with the larger lipoxygenase family, as well as offer guidelines for the de novo design of enzymes that require gaseous molecules as cosubstrates.

FIGURE 6.

Model of gas (O2) migration (green) in WT (A), I553W (B), and L496W SLO (C) based on computational and experimental studies. The SLO protein matrix is depicted in gray, LA is in blue, and the catalytic iron is in magenta. The orange semicircle represents positions of blockages.

Author Contributions

L. C. performed the experiments. J. P. K. and L. C. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Kathleen A. Durkin (Director of the Molecular Graphics and Computation Facility, University of California, Berkeley) for technical assistance with computational modeling. We also thank Dr. Sudhir Sharma (University of California, Berkeley) for frequent helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation GRFP Grants DGE-1106400 (to L. C.) and CHE-0840505 and the National Institutes of Health Grant GM025765 (to J. P. K.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- SLO-1

- soybean lipoxygenase-1

- LA

- linoleic acid

- HPOD

- hydroperoxyoctadecadienoic acid

- ILS

- implicit ligand sampling

- HODE

- hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid.

References

- 1. Lee J. 1., and Goodey N. M. (2011) Catalytic contributions from remote regions of enzyme structure. Chem Rev. 111, 7595–7624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brodkin H., DeLateur N., Somarowthu S., Mills C., Novak W., Beuning P., Dagmar Ringe, and Ondrechen M. (2015) Prediction of distal residue participation in enzyme catalysis. Protein Sci. 24, 762–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mullins L. S., and Raushel F. M. (1992) Channeling of ammonia through the intermolecular tunnel contained within carbamoye phosphate synthetase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 3803–3804 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knapp M. J., Seebeck F. P., and Klinman J. P. (2001) Steric control of oxygenation regiochemistry in soybean lipoxygenase-1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 2931–2932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen J., Kim K., King P., Seibert M., and Schulten K. (2005) Finding gas diffusion pathways in proteins: application to O2 and H2 transport in CpI [FeFe]-hydrogenase and the role of packing defects. Structure 13, 1321–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saam J., Ivanov I., Walther M., Holzhutter H. G., and Kuhn H. (2007) Molecular dioxygen enters the active site of 12/15-lipoxygenase via dynamic oxygen access channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13319–13324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson B. J., Cohen J., Welford R. W., Pearson A. R., Schulten K., Klinman J. P., and Wilmot C. M. (2007) Exploring molecular oxygen pathways in Hansenula polymorpha copper-containing amine oxidas. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17767–17776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leroux F., Dementin S., Burlat B., Cournac L., Volbeda A., Champ S., Martin L., Guigliarelli B., Bertrand P., Fontecilla-Camps J., Rousset M., and Leger C. (2008) Experimental approaches to kinetics of gas diffusion in hydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1188–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luna V. M., Chen Y., Fee J. A., and Stout C. D. (2008) Crystallographic studies of Xe and Kr binding within the large internal cavity of cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus: structural analysis and role of oxygen transport channels in the heme-Cu oxidases. Biochemistry 47, 4657–4665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen L., Lyubimov A. Y., Brammer L., Vrielink A., and Sampson N. S. (2008) The binding and release of oxygen and hydrogen peroxide are directed by a hydrophobic tunnel in cholesterol oxidase. Biochemistry 47, 5368–5377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomita A., Sato T., Ichiyanagi K., Nozawa S., Ichikawa H., Chollet M., Kawai F., Park S. Y., Tsuduki T., Yamato T., Koshihara S. Y., and Adachi S. (2009) Visualizing breathing motions of internal cavitiesnin concert with ligand migration in myoglobin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2612–2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dementin S., Leroux F., Cournac L., de Lacey A. L., Volbeda A., Leger C., Burlat B., Martinez N., Champ S., Martin L., Sanganas O., Haumann M., Fernandez V. M., Guigliarelli B., Fontecilla-Camps J. C., and Rousset M. (2009) Introduction of methionines in the gas channel makes [NiFe] hydrogenase aero-tolerant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10156–10164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scorciapino M. A., Robertazzi A., Casu M., Ruggerone P., and Ceccarelli M. (2009) Breathing motions of a respiratory protein revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 11825–11832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saam J., Rosini E., Molla G., Schulten K., Pollegioni L., and Ghisla S. (2010) O2 reactivity of flavoproteins: dynamic access of dioxygen to the active site and role of a H+ relay system in d-amino acid oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24439–24446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Song W. J., Gucinski G., Sazinsky M. H., and Lippard S. J. (2011) Tracking a defined route for O2 migration in a dioxygen-activating diiron enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 14795–14800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winter M. B., Herzik M. A Jr., Kuriyan J., and Marletta M. A. (2011) Tunnels modulate ligand flux in a heme nitric oxide/oxygen binding (H-NOX) domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E881–E889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang P. H., and Blumberger J. (2012) Mechanistic insight into the blocking of CO diffusion in [NiFe]-hydrogenase mutants through multiscale simulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 6399–6404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Minor W., Steczko J., Stec B., Otwinowski Z., Bolin J. T., Walter R., and Axelrod B. (1996) Crystal structure of soybean lipoxygenase −1 at 1.4 A resolution. Biochemistry 35, 10687–10701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Knapp M. J., and Klinman J. P. (2003) Kinetic studies of oxygen reactivity in soybean lipoxygenase-1. Biochemistry 42, 11466–11475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chovancova E., Benes P., Strnad O., Brezovsky J., Kozlikova B., Gora A., Sustr V., Klvana M., Medek P., Biedermannova L., Sochor J., and Damborsky J. (2012) CAVER 3.0: a tool for the analysis of transport pathways in dynamic protein structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Humphrey W., Dalke A., and Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 14, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Case D. A., Darden T. A., Cheatham I. i. i., Simmerling C. L., Wang J., Duke R. E., Luo R., Walker R. C., Zhank W., and Merz K. H. (2010) AMBER 11, University of California, San Francisco, p. 142 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., and Klein M. L. (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giammona D. A. (1984) An Examination of Conformational Flexibility in Porphyrins and Bulky-ligand Binding in Myoglobin. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Davis, CA [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang J., Cieplak P., and Kollman P. (2000) How well does a restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) model perform in calculating conformational energies of organic and biological molecules? J. Comput. Chem. 21, 1049–1074 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hatcher E., Soudackov A. V., and Hammes-Schiffer S. (2007) Proton-coupled electron transfer in soybean lipoxygenase: dynamical behavior and temperature dependence of kinetic isotope effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 187–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edwards S. J., Soudackov A. V., and Hammes-Schiffer S. (2010) Impact of distal mutation on hydrogen transfer interface and substrate conformation in soybean lipoxygenase. J. Phys. Chem. B. 114, 6653–6660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cohen J., Olsen K. W., and Schulten K. (2008) Finding gas migration pathways in proteins using implicit ligand sampling. Methods Enzymol. 437, 439–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rickert K. W., and Klinman J. P. (1999) Nature of hydrogen transfer in soybean lipoxygenase 1: separation of primary and secondary isotope effects. Biochemistry 38, 12218–12228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meyer M. P., Tomchick D. R., and Klinman J. P. (2008) Enzyme structure and dynamics affect hydrogen tunneling: the impact of a remote side chain (I553) in soybean lipoxygenase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1146–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coffa G., Schneider C., and Brash A. R. (2005) A comprehensive model ofpositional and stereo control in lipoxygenases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu S., Sharma S. C., Scouras A. D., Soudackov A. V., Carr C. A. M., Hammes-Schiffer S., Alber T., and Klinman J. P. (2014) Extremely elevated room-temperature kinetic isotope effects quantify the critical role of barrier width in enzymatic C–H activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8157–8160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berry H., Debat H., and Garde V. L. (1998) Oxygen concentration determines regiospecificity in soybean lipoxygenase-1 reaction via a branched kinetic scheme. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2769–2776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baron R., Riley C., Chenprakhon P., Thotsaporn K., Winter R. T., Alfieri A., Forneris F., van Berkel W. J., Chaiyen P., Fraaije M. W., Mattevi A., and McCammon J. A. (2009) Multiple pathways guide oxygen diffusion into flavoenzyme active sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10603–10608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liebgott P. P., Leroux F., Burlat B., Dementin S., Baffert C., Lautier T., Fourmond V., Ceccaldi P., Cavazza C., Meynial-Salles I., Soucaille P., Fontecilla-Camps J. C., Guigliarelli B., Bertrand P., Rousset M., and Leger C. (2010) Relating diffusion along the substrate tunnel and oxygen sensitivity in hydrogenase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ivanov I., Heydeck D., Hofheinz K., Roffeis J., O'Donnell V. B., Kuhn H., and Walther M. (2010) Molecular enzymology of lipoxygenases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 503, 161–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glickman M. H., and Klinman J. P. (1996) Lipoxygenase reaction mechanism: demonstration that hydrogen abstraction from substrate precedes dioxygen binding during catalytic turnover. Biochemistry 35, 12882–12892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]