Abstract

Objectives.

Despite a growing body of literature documenting the influence of social networks on health, less is known in other parts of the world. The current study investigates this link by clustering characteristics of network members nominated by older adults in Lebanon. We then identify the degree to which various types of people exist within the networks. This study further examines how network composition as measured by the proportion of each type (i.e., type proportions) is related to health; and the mediating role of positive support and trust in this process.

Method.

Data are from the Family Ties and Aging Study (2009). Respondents aged ≥60 were selected (N = 195) for analysis.

Results.

Three types of people within the networks were identified: Geographically Distant Male Youth, Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family, and Close Family. Having more Geographically Distant Male Youth in one’s network was associated with health limitations, whereas more Close Family was associated with no health limitations. Positive support mediated the link between type proportions and health limitations, whereas trust mediated the link between type proportions and depressive symptoms.

Discussion.

Results document links between the social networks and health of older adults in Lebanon within the context of ongoing demographic transitions.

Key Words: Depressive symptoms, Health limitations, Lebanon, Social networks, Social support, Trust.

The link between social relationships and health has long been established in the U.S. and other high-income countries (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). Much less is known, however, about this link in other parts of the world. Examining how social networks influence health among older adults in Lebanon, a middle-income country, is timely given it is currently undergoing a demographic transition characterized by declining fertility rates, increased emigration of younger adults, and increasing numbers of older adults (Yount & Sibai, 2009). In Lebanon, 10% of the population are older adults, a number fast increasing and higher than any other country in the Arab region (United Nations, 2010). With no government safety net, older adults in Lebanon rely heavily on family and other social resources for physical and mental health needs (Abyad, 2001).

New directions in egocentric social network research among older adults have highlighted how grouping people together with similar types of networks can yield new and important insights (Fiori, Antonucci, & Akiyama, 2008; Litwin & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011). This approach clusters people together based on them having similar aggregated network characteristics (e.g., average age of all network members, proportion of network members that are family, etc.). We advance this work by identifying types of people within the social networks of older adults in Lebanon, that is, types of network members. This approach is based on the assumption networks are comprised of unique groups of people, which can be identified using attributes of the individual network members (i.e., age, relationship to the ego/focal person, etc.). The extent to which these types of networks members are present within the networks of older adults, that is, type proportions, may uniquely shape health outcomes. Moreover, social networks represent the structure of social relationships whose effects on health may be understood through various mechanisms (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980; Pollack & von dem Knesebeck, 2004). Positive support and trust are hypothesized as two possible mechanisms through which social networks influence health.

In the current study, we build upon previous research by focusing on types of network members to investigate the following three research questions: (a) What types of network members are present in the social networks of older adults in Lebanon? (b) Is network composition, as measured by the proportions of these types within the networks of older adults in Lebanon related to health? (c) Are the links between network member type proportions and health mediated by positive support and trust in others?

Social and Cultural Context of Aging in Lebanon

Family demography has shifted dramatically in Lebanon over the last few decades. For instance, fertility rates decreased from an average of five children in the early 1970s to just under two in 2004 (Lebanese Information Center, 2013). The average household size today is approximately four persons (Central Administration of Statistics, 2012). Life expectancy has also increased: men live on average 78 years and women 82 years (World Health Organization, 2012). Moreover, today’s Lebanese older adults experienced a protracted Civil War (1975–1990), as well as ongoing political strife (Ajrouch, Abdulrahim, & Antonucci, 2013). Such events have diminished the government’s ability to provide for Lebanese elders. The weak welfare state means family members are the only major resource available to meet the needs of older adults. Conclusions concerning social relations in the West may not always apply in the Lebanese context. In Lebanon men and women have been found to be equally relational (Ajrouch, Yount, Sibai, & Roman, 2013; Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Abdulrahim, 2014; Joseph, 1993). Gender differences are minimal concerning the structure, type and quality of social relations, but there are clear gender-based expectations concerning responsibility and care for family members. Male relatives in general, and the eldest son in particular are responsible for the welfare of parents in later life (Joseph, 1994). Nevertheless, economic factors influence living arrangements. Financially well-off elders are more likely to live on their own than with children (Tohme, Yount, Yassine, Shideed, & Sibai, 2011) and older Lebanese women are more likely to live alone than men. The continuing reliance on family for care will face major challenges in the future as out-migration among youth increases due to limited economic opportunities and continuing political instabilities within Lebanon (Ajrouch et al. 2013; Central Administration of Statistics, 2012). Cultural ideals concerning the care and well-being of older adults in Lebanon are challenged by demographic shifts and pragmatic realities of everyday living.

Theoretical Perspective

The Convoy Model of Social Relations provides a framework for understanding the multiple dimensions of social relationships and their effects on health in varying contexts. Convoys are conceptualized as a person’s social network, comprised of people who surround an individual, protect and socialize, and shape her/his health and well-being across the life course (Antonucci, 2001). The Convoy Model has been successfully applied in a number of countries (Antonucci, Birditt, & Ajrouch, 2011).

According to the Convoy Model, social networks can be described in terms of their structural characteristics, (e.g., size and composition), which are hypothesized to directly influence health and indirectly through the mobilization of support (Antonucci & Ajrouch, 2007). This support can be both positive (e.g., help when sick) and negative (e.g., demanding). In this study we focus on positive support as a potential mechanism through which social networks may influence functional and mental health among Lebanese older adults.

We also propose to expand the Convoy Model’s social network-health mediation hypothesis to include trust in others as another potential mediator through which networks can influence health. Trust is a central component of social capital, a concept that has received much attention in health research (Kawachi, 2006), and is particularly relevant in a Lebanese context given the country’s 15 year-long Civil War and ongoing political divisions. Furthermore, trust may matter more for health in countries where there are insufficient social safety nets (Kawachi, 2006).

Social Networks and Health

A sizeable literature has documented social networks are linked to a number of health outcomes (House et al., 1988), particularly functional health among older adults (Unger, McAvay, Bruce, Berkman, & Seeman, 1999). A concept in the social network literature gaining increased attention is network type (Litwin & Landau, 2000). This concept refers to the structural whole of a person’s social relationships defined by a range of network characteristics (e.g., size, composition, etc.) (Litwin, 1995). Consistent network types have been identified: diverse, friend-focused, family-focused, and restricted (Fiori et al., 2008; Litwin, 2001; Wenger, 1997). Research comparing network types in the U.S. and Japan found the presence of culturally specific types (Fiori et al., 2008), suggesting the need for further research on network types in diverse cultural settings.

Network types have been shown to be associated with health. In particular, Litwin and Stoeckel (2013) found older adults with either diverse or friend/neighbor-focused networks reported fewer difficulties performing instrumental activities of daily living compared with those with restricted networks. In terms of mental health, networks with strong heterogeneous ties (i.e., different ages, social classes, etc.) have been linked to more positive mental health (Erickson, 2003). Similarly, studies of network types have found diverse networks (i.e., mix of family and friends) were related to fewer depressive symptoms (Fiori et al., 2008; Litwin, 2001). Just as previous research has found cultural variations in network types, variations in how these types are associated with health have also been documented. For example, Fiori and colleagues (2008) found Americans with restricted (i.e., smaller size and mostly family) networks reported more depression compared with Americans with other types, whereas in Japan network type was not associated with mental health.

A more recent approach used to examine the effects of networks on health involves the study of types of people within social networks (Webster & Antonucci, 2011). A focus on types of network members diverges from the network typology approach by identifying multiple clusters of network members having similar attributes within social networks. These types can then be used as indicators of network composition and linked to the ego/focal person’s health.

Mechanisms: Support and Trust

Social support and trust represent two mechanisms through which social networks may influence health. The influence of networks on social support has not always been consistent. Among African American mothers, Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn, and Ismail (2010) found larger networks were related to more perceived instrumental support (e.g., help with errands). Larger networks are often associated with more support as they provide a larger pool of persons to call upon when in need. However, evidence regarding other network characteristics and relationship qualities are less consistent. For example, when examining this link using network types, Litwin and Landau (2000) found two distinct types were related to similar levels of support. Although both networks were similar in size and extended family composition, one network consisted mostly of close ties whereas the other mostly weaker ties.

The links between support quality and health have also been established. Fiori, McIlvane, Brown, and Antonucci (2006) found a linear association between more positive support and fewer depressive symptoms among Americans. In contrast, Ajrouch and colleagues (2013) found older Lebanese adults with both low and high positive support reported more depressive symptoms, but those with moderate levels reported the fewest. The link between social support and health is an area in need of further examination.

Feelings of trust also have important links to both social networks and health. Social networks composed of similar people are thought to foster support, whereas social networks comprised of dissimilar persons connected by weak ties may provide wider access to resources (Wellman & Wortley, 1990). Similarly, Ferlander (2007) notes networks made up of close homogenous persons (i.e., same age, social class, etc.) tend to provide more support. However, Portes (1998) argues these same networks may also lead to social exclusion and mistrust outside the network. Having trust in others, moreover, has been found to have a consistent positive impact on a range of health outcomes. Specifically, having more trust in others has been linked to fewer functional limitations and less depression (Pollack & von dem Knesebeck, 2004). Such findings suggest it is necessary to examine consequences of social networks on both physical and mental health, via additional underexplored pathways, and in diverse cultural contexts.

Study Objectives

To explore mechanisms through which social networks influence health among older adults within the Lebanese context, we focus on three research questions and related hypotheses:

Research question # 1.

What types of network members are present in the social networks of older adults in Lebanon? Due to the documented importance of family for the provision of support for older adults in Lebanon (Abyad, 2001) we hypothesize one type, made up predominantly of family will be most prominent, and will be described as close, geographically and emotionally.

Research question #2.

Is network composition, as measured by the proportions of the types of network members identified within the social networks of the older adults associated with health (i.e., functional limitations and depression)? As noted previously, close familial ties, especially with adult children and in particular eldest sons, play essential roles in organizing and providing care for older adults in Lebanon. Therefore, we hypothesize respondents with a greater proportion of network members with the following clustered attributes: young to middle-aged, predominantly family, male, geographically and emotionally close, and in frequent contact, will report better functional and mental health.

Research question #3.

Are the links between network member type proportions and health mediated by positive support and trust in others? We hypothesize support and trust will mediate health in different ways. In particular, we expect respondents whose networks consist of a higher proportion of people similar to themselves (i.e., geographically and emotionally close family of similar age) will report more positive support, but also less trust in others due to the insular nature of the network. As a result this type proportion will have a positive influence on functional and mental health when operating through positive support, but a negative influence when operating through trust.

Method

Sample

Data are from the Family Ties and Aging Study (see Abdulrahim, Ajrouch, Jammal, & Antonucci, 2012). The study sample included 500 adults aged 18 years or older residing in greater Beirut, with oversampling of adults age ≥60. Data were collected in 2009 through in-person interviews in respondent homes lasting approximately 1hr. The response rate was 64%. Households were randomly selected for participation from the three administrative districts of Beirut in addition to Aley, Baabda, and Metn. For this study, respondents aged ≥60 were selected (N = 195).

Measures

Outcomes.

Health Limitation assessed if respondents were limited in any way because of their health (no = 0; yes = 1). Depressive Symptoms were measured using the 11-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression sum composite scale (Cronbach’s alpha for study sample = .83). These items originally developed by Radloff (1977) have been validated in Arabic (Kazarian & Taher, 2010). Respondents were asked to respond about the experience of depressive symptoms during the past week on a scale ranging from 0 (rarely/none of the time) to 3 (mostly/all of the time). Two positively worded items (i.e., just as good as others and hopeful about future) were reverse coded for inclusion in the scale.

Predictors.

Types of Members within Social Networks were identified using six criteria describing respondents’ social network members, which were assessed using the hierarchical mapping technique (see Antonucci, 1986). Emotional Closeness for the first 10 people aged 13 or older was coded as not so close/distant (i.e., middle or outer circle) = 0 and very close (i.e., inner circle) = 1. Respondents were then asked questions about these first 10 people including: a) Geographic Proximity, coded as lives greater than ½ hr from respondent = 0 and lives within ½ hr = 1; b) Age measured in years; c) Contact Frequency, measured on a 5-point scale ranging from irregularly = 1 to everyday = 5; d) Gender, coded as male = 0 and female = 1; and e) Relationship Type, coded as non-family = 0 and family = 1.

Positive support.

Respondents were asked to rate the positive aspects of the support received from their mother, father, spouse/partner, child relied on most, sibling relied on most, best/closest friend, and the first person nominated in their network (if not already included). On a 5-point scale (disagree = 1; agree = 5) respondents were asked to rate their agreement with five statements which tap into emotional and instrumental aspects of each relationship (e.g., I can share my very private feelings and concerns with (____)”; “I feel my (____) would help me out financially if I needed it”). A mean composite scale was created for each relationship, and then an overall positive support scale was created by averaging all reported relationships. Cronbach’s alphas for the study sample ranged from .63 to .91 across the relationships assessed.

Trust in others.

Trust was measured using a 4-item mean composite scale. Respondents were asked how much trust they have in: people in Lebanon, people in their neighborhood, their friends, and their extended family on a 4-point scale (trust them not at all = 1; trust them a lot = 4) (Cronbach’s alpha for study sample = .87).

Covariates.

Demographics including age, gender, marital status, and income, found to be associated with social networks (Antonucci, 2001), were included as covariates. Age was measured in years as of 2009. Gender was coded as male = 0; female = 1. Marital status was coded as not married = 0; married = 1. Income was measured as monthly income from all sources for the respondent and all family members living with them and was coded as less than $500 per month = 1; $500–$1,000 per month = 2; more than $1,000 per month = 3.

Analytic strategy.

To address research question #1, we identify types of social network members by conducting multilevel latent class analysis (MLCA) using Mplus. Latent class analysis (LCA) detects groups of similar cases based on specified criterion variables (Muthén & Muthén, 2000). Because LCA assumes cases are independent, and due to network members being nested within the networks of the respondents who nominated them, MLCA was used (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2008). This approach uses a random intercept to allow the probability of network members assigned to a particular type to vary across primary respondent networks. For the MLCA, all network members nominated by respondents (network members N = 1,090 were the unit of analysis, that is, rows of data represented network members) and six variables describing each network member were used as the criteria to define the types. We conducted seven fixed effects models, allowing for one to seven different types, followed by additional models that included a random intercept. The final number of network member types was decided upon using a combination of criteria including previous theoretical and empirical literature, fit indices, parsimony, relevance, and face validity of the identified types.

To examine research questions 2 and 3, each network members’ assigned type was aggregated to the primary respondent-level. This was done by creating a dataset in which rows represented respondents and separate variables were included for each of their network members, documenting the specific type the network member was assigned. For each respondent, we then calculated the proportion of their network comprised of each type. For example, for the first network member type, Geographically Distant Male Youth, we first counted the number of network members assigned to that group separately for each respondent, and then divided by the total number of network members nominated by that respondent (up to 10). We followed the same procedure to calculate the proportions of the other types of network members, Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family and Close Family. As proportions, each composition variable in the respondent-level dataset ranged from 0 to 1.

To examine the association between each type proportion and health we conducted logistic and linear regression analyses using the respondent-level dataset. A separate model was conducted for each type proportion. This approach was used to account for interdependencies and redundancy between the type proportions, which when added together equal 1 for any given respondent. Thus, a higher proportion of a specific type of network member was strongly associated with respondents having a lower proportion of other types. Because three types of network members were identified within the networks, a total of three models were tested for each health outcome, each including a different type proportion variable. Due to all respondents having some value (ranging from 0 to 1) on all three proportion variables, all respondents (N = 195) were included in all models.

To examine the mediating role of support and trust in the link between the type proportions and health we used the following criteria discussed by Baron and Kenny (1986) including: (a) type proportion significantly associated with mediator (i.e., positive support and/or trust); and (b) mediator associated with outcome (i.e., health limitation and/or depressive symptoms). We did not require the type proportion to be significantly related to health for mediation to exist to allow for possible inconsistent mediation (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample ranged in age from 60 to 91 with a mean of 70.4 (SD = 7.6), with 52% women. Thirty percent reported household family income ≤ $500/month, 53% $500–$1,000/month, and 17% reported monthly income > $1,000/month. Respondents reported highly positive support (mean = 4.6, SD = 0.5; range 2.6–5). Trust in others on average was 2.8 (SD = 0.8; range 1–4). Just under one-third (29%) of respondents were limited due to health, and reported an average depressive symptom score of 11.3 (SD = 7.3; range 0–31).

Respondents nominated on average 6.1 people in their social networks (SD = 3.3; range: 0–17). Only 8% of the sample (N = 15 of 195) nominated more than 10 people. On average, the proportion of the total network consisting of inner circle members (i.e., those closest) was .78 (SD = 0.24), compared with a proportion of .17 (SD = 0.19) nominated in the middle circle, and .05 (SD = 0.10) in the outer circle.

What types of network members are present in the social networks of older adults in Lebanon? As Table 1 indicates, the MLCA of social network member characteristics identified three types of network members. When comparing the models we found the random effects model with three types resulted in the best fit (i.e., biggest drop in BIC from previous solution, higher entropy, and no types containing less than 10% of the sample).

Table 1.

Multilevel Latent Class Analysis Fit Indices

| No. of classes | No. of free parameters | Log-likelihood | BIC | Entropy | No. of classes with n < 10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects models (1 level) | |||||

| 2 | 15 | −7745.97 | 15,596.85 | 0.94 | 0 |

| 3 | 22 | −7561.96 | 15,277.78 | 0.97 | 0 |

| 4 | 29 | −7482.28 | 15,167.39 | 0.91 | 1 |

| 5 | 36 | −7272.87 | 14,797.53 | 0.93 | 3 |

| Random effects models (2 levels) | |||||

| 2 | 16 | −7666.14 | 15,444.18 | 0.96 | 0 |

| 3 | 24 | −7454.18 | 15,076.21 | 0.97 | 0 |

| 4 | 32 | −7273.76 | 14,771.33 | 0.98 | 2 |

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the N = 1,090 network members nominated by the 195 respondents. Among the population of network members, 77% were very close to the primary respondent, 78% lived within ½ hr, the average age was just under 43 (SD = 16.4), frequency of contact was on average weekly, just under half were women (49%), and 92% were family members. Given the high proportion of family members nominated among the respondents’ first 10 network members, we explored the number and types of family members nominated. We found on average, respondents nominated 5.3 (SD = 2.8; range: 0–10) family members in their social convoys. There was an average of 2.9 (SD = 2.0; range: 0–10) children, 0.6 (SD = 1.3; range: 0–6) siblings, and 2.0 (SD = 2.1; range: 0–10) extended family members.

Table 2.

Attributes of Social Network Members by Network Member Type

| All network members | Geographically distant male youth | Geographically close/ emotionally distant family | Close family | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 1,090) | 14% (N = 154) | 28% (N = 304) | 58% (N = 632) | |

| % Very close | 77 | 74 | 70 | 81 |

| % Geographically proximate | 78 | 13 | 90 | 91 |

| Age: mean (SD, range) | 42.6 (16.4; 13–90) | 37.8 (15.4; 13–88) | 44.2 (16.5; 13–85) | 43.0 (16.4; 13–90) |

| Contact frequency: mean (SD, range) | 4.2 (1.2; 1–5) | 1.7 (0.5; 1–2) | 3.8 (0.4; 3–4) | 5.0 (0.0; 5) |

| % Women | 49 | 36 | 47 | 53 |

| % Family | 92 | 92 | 94 | 91 |

The first network member type was the smallest, containing 14% (N = 154) of the network members. We labeled this type Geographically Distant Male Youth. Network members assigned to this type were emotionally very close, but geographically distant, younger, infrequently in contact with the primary respondent, and predominantly male. The second network member type included 28% (N = 304) of the network members. This type we labeled Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family. Network members assigned to this type were emotionally the least close, but geographically proximate, oldest, had weekly to monthly contact with the primary respondents, and included approximately equal men and women. The third type, the largest, with over half (58%; N = 632) of the network members we labeled Close Family. This type was emotionally and geographically the closest of all three types, and consisted of older network members, were in daily contact with the primary respondent and approximately equally men and women.

When aggregated back to the respondent level (N = 195), each of the three type proportions ranged from 0 to 1, suggesting considerable variability in the presence of these types across networks. The results partially support our hypothesis that a family dominated network member type would be most prominent. We found family comprised the overwhelming majority (91%–94%) of all three types of network members. The findings also partially support our hypothesis that family dominated networks would be emotionally and geographically close. Due to all three types of network members consisting of mostly family, only one (Close Family) supported this hypothesis as these network members were mostly nominated in the inner circle and lived within ½ hr of the primary respondents. The other two family dominated network member types were emotionally close but not geographically close or were emotionally distant and geographically close.

After identifying the types of network members present in the social networks of older adults in Lebanon we explored associations (i.e., correlations and mean differences) between network composition as measured by each type’s proportion within the networks and demographic characteristics. We found gender and income were not related to the proportion of each of the three types of network members. However, we did find younger age was associated with networks comprised of a significantly greater proportion of Geographically Distant Male Youth, and not being married was associated with networks comprised of a significantly greater proportion of Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family.

Is network composition, as measured by the network member type proportions associated with health? As indicated in Table 3 our hypotheses were partially supported in that two of the three type proportions were significantly related to health limitations. Contrary to our hypothesis none of the type proportions were related to depressive symptoms. We found older adults with a larger proportion of their network comprised of Geographically Distant Male Youth had greater odds of having a health limitation (Exp(b) = 5.32; p < .05). This finding supports our hypothesis that a younger geographically distant type of network member would be associated with respondents’ reports of being functionally limited by their health. Also in support of our hypothesis we found older adults with a larger proportion of their network comprised of Close Family had significantly smaller odds of being limited by their health (Exp(b) = .28; p < .05). Lastly, we found no association between the proportion of Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family and having a health limitation.

Table 3.

Influence of Network Member Type Proportions on Health

| Health limitation | Depressive symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | Exp(b) | b (SE) | β | |

| Age | 0.09 (0.02)*** | 1.09 | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.14 |

| Women | 0.22 (0.42) | 1.25 | 3.64 (1.17)** | 0.25 |

| Married | −0.50 (0.43) | 0.61 | 1.48 (1.22) | 0.10 |

| Income | −0.33 (0.24) | 0.72 | −3.12 (0.61)*** | −0.36 |

| Prop. geographically distant | ||||

| Male youth | 1.67 (0.73)* | 5.32 | −0.28 (2.19) | −0.01 |

| R-squarea | .19*** | .18*** | ||

| Age | 0.07 (0.02)** | 1.08 | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.13 |

| Women | 0.22 (0.42) | 1.25 | 3.68 (1.16)** | 0.25 |

| Married | −0.45 (0.44) | 0.64 | 1.66 (1.23) | 0.11 |

| Income | −0.26 (0.24) | 0.78 | −3.08 (0.61)*** | −0.35 |

| Prop. geographically close/emotionally | ||||

| Distant family | 0.67 (0.56) | 1.94 | 1.44 (1.68) | 0.06 |

| R-squarea | .16*** | .18*** | ||

| Age | 0.08 (0.02)** | 1.09 | 0.13 (0.07)* | 0.14 |

| Women | 0.28 (0.43) | 1.33 | 3.69 (1.17)** | 0.25 |

| Married | −0.34 (0.44) | 0.71 | 1.63 (1.23) | 0.11 |

| Income | −0.28 (0.24) | 0.76 | −3.10 (0.61)*** | −0.35 |

| Prop. close | ||||

| Family | −1.27 (0.51)* | 0.28 | −0.93 (1.44) | −0.04 |

| R-squarea | .20*** | .18** | ||

Notes. aPseudo R-square is presented for health limitation model, and adjusted R-square for depressive symptoms.

*p value < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Are the links between network member type proportions and health mediated by positive support and trust in others? As Table 4 indicates, and in support of our hypotheses, all three type proportions were related to both positive support and trust in others.

Table 4.

Influence of Network Member Type Proportions on Positive Support and Trust in Others

| Positive support | Trust in others | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | |

| Age | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.12 | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.04 |

| Women | 0.07 (0.08) | 0.08 | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.02 |

| Married | −0.10 (0.08) | −0.11 | −0.10 (0.14) | −0.06 |

| Income | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.05 | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.05 |

| Prop. geographically distant | ||||

| Male youth | −0.31 (0.14)* | −0.17 | 0.62 (0.25)* | 0.19 |

| Adjusted R-square | .05* | .02 | ||

| Age | 0.01 (0.00)* | 0.17 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.09 |

| Women | 0.07 (0.08) | 0.07 | 0.03 (0.13) | 0.02 |

| Married | −0.13 (0.08) | −0.15 | −0.03 (0.14) | −0.02 |

| Income | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.02 | 0.07 (0.07) | 0.08 |

| Prop. geographically close/emotionally | ||||

| Distant family | −0.37 (0.11)** | −0.25 | 0.70 (0.19)*** | 0.27 |

| Adjusted R-square | .09** | .05* | ||

| Age | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.13 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.05 |

| Women | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.06 | 0.05 (0.13) | 0.03 |

| Married | −0.15 (0.08) | −0.16 | −0.00 (0.14) | −0.00 |

| Income | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.04 | 0.06 (0.07) | 0.06 |

| Prop. close | ||||

| Family | 0.40 (0.09)*** | 0.32 | −0.78 (0.16)*** | −0.35 |

| Adjusted R-square | .13*** | .10*** | ||

Notes. *p value < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Positive Support

We found older adults with a greater proportion of their network comprised of Geographically Distant Male Youth (β = −.17; p < .05) and Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family (β = −.25; p < .01) were associated with less positive support. In contrast, respondents with a greater proportion of network members who were Close Family (β = .32; p < .001) reported more positive support. These findings support our hypotheses that network members different than the respondent would be linked to less support, whereas those closer and more similar would be associated with more support.

Trust in Others

We found support for our hypotheses concerning trust. We hypothesized respondents whose networks consist of more people who are different than themselves will report greater trust in others, whereas those whose networks consist of more people similar to themselves will report less trust. Specifically, we found networks comprised of more Geographically Distant Male Youth (β = .19; p < .05) and Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family (β = .27; p < .001) were associated with more trust in others. In contrast, respondents with more Close Family (β = −.35; p < .001) in their networks reported less trust.

Positive Support, Trust and Health

As Table 5 indicates, in all three type proportion models, we found support for the hypothesis that more positive support was significantly related to smaller odds of having a health limitation (Exp(b) = .34, p < .01; .32, p < .01; .39, p < .05). However, contrary to our hypothesis, trust in others was not related to having a health limitation.

Table 5.

Influence of Network Member Type Proportions, Positive Support, and Trust on Health

| Health limitation | Depressive symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | Exp(b) | b (SE) | β | |

| Age | 0.10 (0.03)*** | 1.10 | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.13 |

| Women | 0.30 (0.43) | 1.35 | 3.76 (1.16)** | 0.26 |

| Married | −0.68 (0.44) | 0.51 | 1.26 (1.21) | 0.09 |

| Income | −0.33 (0.25) | 0.72 | −3.08 (0.61)*** | −0.35 |

| Prop. geographically distant | ||||

| Male youth | 1.44 (0.76) | 4.22 | 0.43 (2.24) | 0.01 |

| Positive support | −1.07 (0.39)** | 0.34 | −0.63 (1.13) | −0.04 |

| Trust in others | −0.09 (0.24) | 0.91 | −1.55 (0.64)* | −0.17 |

| R-squarea | .24*** | .19*** | ||

| Age | 0.09 (0.02)*** | 1.09 | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.12 |

| Women | 0.32 (0.43) | 1.38 | 3.79 (1.15)** | 0.26 |

| Married | −0.64 (0.45) | 0.53 | 1.57 (1.23) | 0.11 |

| Income | −0.28 (0.25) | 0.75 | −3.01 (0.61)*** | −0.34 |

| Prop. geographically close/emotionally | ||||

| Distant family | 0.27 (0.61) | 1.31 | 2.57 (1.78) | 0.11 |

| Positive support | −1.13 (0.40)** | 0.32 | −0.26 (1.14) | −0.02 |

| Trust in others | −0.06 (0.24) | 0.94 | −1.76 (0.65)** | −0.19 |

| R-squarea | .22*** | .20*** | ||

| Age | 0.09 (0.03)*** | 1.09 | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.13 |

| Women | 0.34 (0.43) | 1.40 | 3.82 (1.15)** | 0.26 |

| Married | −0.53 (0.45) | 0.59 | 1.60 (1.23) | 0.11 |

| Income | −0.28 (0.25) | 0.76 | −3.03 (0.61)*** | −0.35 |

| Prop. close | ||||

| Family | −0.98 (0.57) | 0.38 | −2.31 (1.61) | −0.11 |

| Positive support | −0.96 (0.41)* | 0.39 | −0.11 (1.18) | −0.01 |

| Trust in others | −0.17 (0.25) | 0.85 | −1.85 (0.67)** | −0.20 |

| R-squarea | .24*** | .20*** | ||

Notes. aPseudo R-square is presented for health limitation model, and adjusted R-square for depressive symptoms; *p value < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

This was not the case when examining how these same factors were related to depressive symptoms. First, in support of our hypothesis, in all type proportion models, more trust in others was related to fewer depressive symptoms (β = −.17, p < .05; −.19, p < .01; −.20, p < .01). However, contrary to our hypothesis, positive support was not related to depressive symptoms.

Mediation

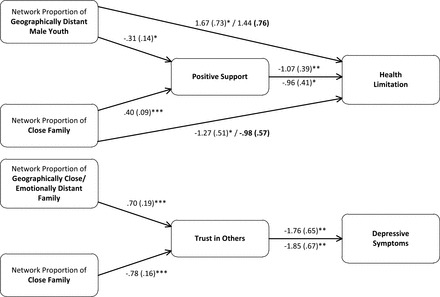

Table 5 presents the associations of each type proportion with health limitation and depressive symptoms, including both positive support and trust as covariates. In support of our hypotheses, we found mediation for both health limitations and depressive symptoms. Figure 1 provides a summary of results pertaining to our mediation hypotheses.

Figure 1.

The mediating role of positive support and trust in others on health. Depicted are unstandardized regression coefficients and standard error. *p value < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

We found the effects of both the proportion of Geographically Distant Male Youth and Close Family on health limitations were completely mediated by positive support (i.e., significant main effects of both type proportions were not significant when positive support was included as a covariate). As expected, more Geographically Distant Male Youth was linked with less positive support and in turn linked to greater odds of having a health limitation. In contrast, more Close Family was linked to more positive support and in turn less odds of being limited by health. Contrary to our hypothesis, the proportion of Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family’s effect on health limitation was not mediated by positive support. Additionally, we did not find support for our hypotheses regarding the mediating role of trust on health limitations.

As hypothesized, the effect of both the proportion of Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family and Close Family on depressive symptoms was mediated by trust in others. Mediation was found despite the lack of a main effect linking the type proportion to depressive symptoms due to inconsistent mediation. In the case of Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family we found the hypothesized positive link to trust, which was related to fewer depressive symptoms (i.e., negative mediation). In contrast, but as predicted, the effect of Close Family was positively mediated by trust due to the negative impact of this type proportion on trust, that is, greater proportion associated with less trust, which in turn was linked to more depressive symptoms.

Discussion

This study contributes to the growing literature exploring pathways through which social networks are related to physical and mental health. Despite evidence linking the characteristics of support networks to health, less is known about this process in the Arab cultural context where cultural ideals presume strong social relations. A focus on Lebanon is particularly useful to help further advance understanding of social network effects on health and timely, given the aging Lebanese population. The results from this study provide critical theoretical and policy implications.

Theoretical Implications

These results provide support for the application of the Convoy Model to social relationships of older adults in Lebanon. First, the identification of three distinct types of network members within the social networks of older adults in Lebanon using the Convoy Model’s constructs of social network structure suggests their valid applicability in this context. The fact that we identified three unique types of people comprising the networks of older adults suggests considerable diversity in the composition of social networks in Lebanon, though all three were family dominated. This finding is consistent with previous research documenting the importance of family relations, both immediate and extended, among older adults in Lebanon (Mehio-Sibai, Beydoun, & Tohme, 2009). The lack of a network member type with a mix of friends and family, which has been consistently documented as a network type in high-income countries (Fiori et al., 2008), provides further evidence for the important role of national context in shaping social relations. Documenting such variations is the first step in understanding how social networks differentially affect health in diverse contexts.

The complex role of younger network members was evident in the small but significant network type of Geographically Distant Male Youth. This type may represent a generation of younger adults looking for economic opportunity outside Lebanon (Ajrouch et al., 2013). Their presence and the fact that most are male raises concern for future care needs of older adults in Lebanon, as it is customary for many low-income single or widowed older women to live with adult sons (Mehio-Sibai et al., 2009). Whereas the distant economic opportunity may allow the youth to provide financially for their aging parent, the lack of a physical presence may affect their mental health.

The network member type proportions were associated with functional health limitations. In particular, our finding that older adults with more people similar to themselves (i.e., older, emotionally and geographically close) in their network were less likely to be limited by health is consistent with Ferlander’s (2007) proposition that homogeneous networks tend to be linked to support provision. However, our findings contradict some previous empirical findings. For example, Litwin and Stoeckel (2013) found older adults with diverse or friend-focused networks reported fewer health limitations. This discrepancy may be attributable to cultural variations in patterns of social relations as well as different patterns related to health in non-western settings. Also, consistent with Ferlander’s propositions was our finding that networks comprised of more Geographically Distant Male Youth were linked to health limitations. Though espousing strong emotional bonds, these network members who are geographically distant and infrequently in contact, may be linked with a lack of hands on support necessary to mitigate health problems.

Social network member type proportions did not predict mental health. This was surprising given consistent findings linking network types to mental health in previous studies (Erickson, 2003; Fiori et al., 2008; Litwin, 2001). The fact that we did not find a link between the type proportions and mental health may be attributable to the minimal presence of non-family members within the social networks of older adults in Lebanon. In high-income settings, the diverse (i.e., mix of family and non-family) network type was linked to better mental health (Fiori et al., 2008). Possibly, the expectation that family members comprise such a large part of social networks in Lebanon explains why this aspect of network composition is not associated with mental health. Furthermore, the findings suggest network diversity in this context may be better captured by distinguishing between immediate and extended family as opposed to family and non-family.

Second, our findings provide support for the Convoy Model’s proposition about the mediating role of support in the link between social network structure and health. We focused on the unique role of positive support in this process, and found this hypothesis appears only to be supported when examining functional health. However, the lack of evidence showing a mediating effect of support on mental health reinforces the need to continue to examine social networks and their links to health in diverse cultural settings.

Positive support differentially mediated the effects of homogeneous (i.e., Close Family) and heterogeneous (i.e., Geographically Distant Male Youth) network members on functional health. The increased provision of support by Close Family and the subsequent positive link between this support and no health limitations, suggests the importance of close hands-on care to help older adults in Lebanon maintain functional health. In contrast, older adults with more Geographically Distant Male Youth in their network reported less support, which placed them at an increased risk of functional health limitations. This suggests if more youth in Lebanon explore economic opportunities elsewhere, a growing number of older adults will be left in need of instrumental support to help maintain functional independence.

The lack of an association between Geographically Close/Emotionally Distant Family and functional health was unexpected. However, we did expect this group would be linked to lower perceived support. These findings together suggest most care provided to older adults in Lebanon is secured from close immediate family members. This is further supported by the lack of a link between trust in others and functional health. In sum, findings suggest care is provided by those already close and trust does little to alter this process.

Another goal of this study was to expand the Convoy Model’s mediating hypothesis to include trust. Our findings support this hypothesis and suggest trust is an important resource shaped by social networks, with tangible consequences for mental health. Findings are consistent with Portes’ (1998) argument that homogeneous networks, despite their tendency to provide more support, also have a darker side in that they are insular and may lead to mistrust of others. Additionally, our study provides evidence that in a Lebanese context, trust is particularly important for mental health. Overall, these findings suggest examining the interplay of distinct components of social capital can yield interesting and new insights into how social networks influence health.

Health Policy Implications

In light of the aging Lebanese population, findings from this study highlight health and caregiving needs of older adults in Lebanon. In particular if the trend of youth emigration holds steady or increases, reliance on older close family for support may actually increase. Currently, Geographically Distant Male Youth comprise the smallest portion of older adults’ social networks in Lebanon, but their association with less support and functional health limitations is reason for concern. These trends may eventually limit older adults’ abilities to interact with more emotionally distant network members, who as we have shown, play an instrumental role in promoting mental health.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study was limited in that the data were cross-sectional. Future studies examining mediating processes with longitudinal data can disentangle reciprocal effects. Despite this limitation, findings provide evidence for the proposition that social networks can simultaneously have positive and negative influences on health when operating through mechanisms such as support and trust. Whereas network diversity can lead to more trust, it may put an older adult at risk for a lack of needed instrumental support. In contrast, the presence of mostly close similar others in one’s network may provide the needed support in old age, but may result in mistrust of others leading to diminished mental health.

Nevertheless, results should be interpreted with caution. Due to redundancy of information across the type proportions (i.e., sum across all three for any given respondent equals 1) and resulting multicollinearity, we conducted separate models for each. This approach limited us to examining the association of each type proportion relative to the other two proportions combined. Recommended future directions include utilizing approaches that compare effects of all type proportions separately as well as exploring how various combinations or patterns of network member types are present within networks and uniquely related to health.

In sum, the focus on types of members within networks provides a novel lens on heterogeneity within older adults’ networks that cannot be identified with overarching network types alone. This level of detail allowed us to determine multiple groupings within one network, and investigate how each influences health in unique ways. Findings highlight effects of the ongoing demographic transition occurring in Lebanon on the social networks and health of older adults.

Funding

This work was supported by the Doha International Family Institute; and the Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research. The authors of this research are fully responsible for its content, which does not necessarily reflect views of the funding sources.

Acknowledgements

N. J. Webster planned the study, performed all statistical analyses and wrote the paper. T. C. Antonucci planned the study, supervised data analysis, and revised the manuscript. K. J. Ajrouch planned the study, supervised data analysis, and revised the manuscript. S. Abdulrahim planned the study and revised the manuscript.

References

- Abdulrahim S., Ajrouch K. J., Jammal A., Antonucci T. C. (2012). Survey methods and aging research in an Arab sociocultural context—A case study from Beirut, Lebanon. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 775–782. 10.1093/geronb/gbs083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abyad A. (2001). Healthcare for older persons: A country profile—Lebanon. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 49, 1366–1370. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49268.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch K. J., Abdulrahim S., Antonucci T. C. (2013). Stress, social relations, and psychological health over the life course. GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 15–27. 10.1024/1662–9647/a000076 [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch K. J., Reisine S., Lim S., Sohn W., Ismail A. (2010). Perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress: Does social support matter? Ethnicity & Health, 15, 417–434. 10.1080/13557858.2010.484050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch K. J., Yount K. M., Sibai A. M., Roman P. (2013). A gendered perspective on well-being in later life: Algeria, Lebanon, and Palestine. In McDaniel S., Zimmer Z. (Eds.), Global ageing in the 21st century (pp. 49–77). Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C. (1986). Hierarchical mapping technique. Generations, 10, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support and sense of control. In Birren J. E., Schaie K. W. (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed., pp. 427–453). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Ajrouch K. J. (2007). Social resources. In Mollenkopf H., Walker A. (Eds.), Quality of life in old age (pp. 49–64). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4020-5682-6_4 [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Ajrouch K. J., Abdulrahim S. (2014). Social relations in Lebanon: Convoys across the life course. The Gerontologist. Advance online publication. 10.1093/geront/gnt209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Birditt K. S., Ajrouch K. (2011). Convoys of social relations: Past, present, and future. In Fingerman K. L., Berg C. A., Smith J., Antonucci T. C. (Eds.), Handbook of lifespan development (pp. 161–182). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. (2008). Multilevel mixture models. In Hancock G. R., Samuelsen K. M. (Eds.), Advances in latent variable mixture models (pp. 27–51). Charlotte, NC: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. M., Kenny D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Administration of Statistics. (2012, April). Population and housing characteristics in Lebanon. Statistics in Focus (SIF), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson B. (2003). Social networks: The value of variety. Contexts, 2, 25–31. 10.1525/ctx.2003.2.1.25 [Google Scholar]

- Ferlander S. (2007). The importance of different forms of social capital for health. Acta Sociologica, 50, 115–128. 10.1177/0001699307077654 [Google Scholar]

- Fiori K. L., Antonucci T. C., Akiyama H. (2008). Profiles of social relations among older adults: A cross-cultural approach. Ageing and Society, 28, 203–231. 10.1017/S0144686X07006472 [Google Scholar]

- Fiori K. L., McIlvane J. M., Brown E. E., Antonucci T. C. (2006). Social relations and depressive symptomatology: Self-efficacy as a mediator. Aging and Mental Health, 10, 227–239. 10.1080/13607860500310690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. S., Landis K. R., Umberson D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241, 540–545. 10.1126/science.3399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S. (1993). Connectivity and patriarchy among urban working class families in Lebanon. Ethos, 21, 252–284. 10.1525/eth.1993.21.4.02a00040 [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S. (1994). Brother/sister relationships: Connectivity, love, and power in the reproduction of patriarchy in Lebanon. American Ethnologist, 21, 50–73. 10.1525/ae.1994.21.1.02a00030 [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. L., Antonucci T. C. (1980). Convoys over the life-course: Attachment, roles and social support. In Baltes P. B., Brim O. G. (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (pp. 253–286). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I. (2006). Commentary: Social capital and health: Making the connections one step at a time. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35, 989–993. 10.1093/ije/dyl117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazarian S. S., Taher D. (2010). Validation of the Arabic center for epidemiological studies depression (CES-D) scale in a Lebanese community sample. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26, 68–73. 10.1027/1015–5759/a000010 [Google Scholar]

- Lebanese Information Center. (2013). The Lebanese demographic reality. Beirut, Lebanon: Statistics Lebanon Polling and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H. (1995). The social networks of elderly immigrants: An analytic typology. Journal of Aging Studies, 9, 155–174. 10.1016/0890-4065(95)90009-8 [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H. (2001). Social network type and morale in old age. The Gerontologist, 41, 516–524. 10.1093/geront/41.4.516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H., Landau R. (2000). Social network type and social support among the old-old. Journal of Aging Studies, 14, 213–228. 10.1016/S0890-4065(00)80012-2 [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H., Shiovitz-Ezra S. (2011). The association of background and network type among older Americans is “Who You Are” related to “Who You Are With”? Research on Aging, 33, 735–759. 10.1177/0164027511409441 [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H., Stoeckel K. J. (2013). Social network and mobility improvement among older Europeans: The ambiguous role of family ties. European Journal of Ageing, 10, 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Fairchild A. J., Fritz M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehio-Sibai A., Beydoun M. A., Tohme R. A. (2009). Living arrangements of ever-married older Lebanese women: Is living with married children advantageous? Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 24, 5–17. 10.1007/s10823-008-9057-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B., Muthén L. K. (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 882–891. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack C. E., von dem Knesebeck O. (2004). Social capital and health among the aged: Comparisons between the United States and Germany. Health & Place, 10, 383–391. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1–24. 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1 [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [Google Scholar]

- Tohme R. A., Yount K. M., Yassine S., Shideed O., Sibai A. M. (2011). Socioeconomic resources and living arrangements of older adults in Lebanon: Who chooses to live alone? Ageing and Society, 31, 1–17. 10.1017/S0144686X10000590 [Google Scholar]

- Unger J. B., McAvay G., Bruce M. L., Berkman L., Seeman T. (1999). Variation in the impact of social network characteristics on physical functioning in elderly persons: MacArthur studies of successful aging. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 54, S245–S251. 10.1093/geronb/54B.5.S245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2010). Demographic and social statistics. Retrieved September 5, 2012, from http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/socind/default.htm

- Webster N. J., Antonucci T. C. (2011, November). Differing perspectives on ego-centric social network characteristics: Individuals within versus aggregated networks. Paper presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman B., Wortley S. (1990). Different strokes from different folks: Community ties and social support. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 558–588. org/10.1086/229572 [Google Scholar]

- Wenger G. C. (1997). Social networks and the prediction of elderly people at risk. Ageing and Mental Health, 1, 311–320. 10.1080/13607869757001 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2012). Country profile: Lebanon. Retrieved May 15, 2014, from http://www.who.int/countries/lbn/en/

- Yount K. M., Sibai A. M. (2009). The demography of aging in Arab countries. In Uhlenberg P. (Ed.), International handbook of population aging (pp. 277–315). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4020-8356-3_13 [Google Scholar]