Abstract

INTRODUCTION

In preclinical studies, surgery/anesthesia contribute to cognitive decline and enhance neuropathologic changes underlying Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Nevertheless, the link between surgery, anesthesia, apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE4), and AD remains unclear.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of two prospective longitudinal aging studies. Mixed-effects statistical models were used to assess the relationship between surgical/anesthetic exposure, the APOE genotype, and rate of change in measures of cognition, function, and brain volumes

RESULTS

The surgical group (n=182) experienced a more rapid rate of deterioration compared to the nonsurgical group (n=345) in several cognitive, functional, and brain MRI measures. Further, there was a significant synergistic effect of anesthesia/surgery exposure and presence of the APOE4 allele in the decline of multiple cognitive and functional measures.

DISCUSSION

These data provide insight into the role of surgical exposure as a risk factor for cognitive and functional decline in older adults.

Keywords: Epidemiology, anesthesia, surgery, cognitive decline, postoperative, apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE4), Alzheimer’s disease, cohort study, volumetric MRI

1. Background

Individuals aged 65 years and older receive more than 1/3 of the over 40 million anesthetics delivered yearly in the United States, and evidence suggests that older adults are most at risk for postoperative deleterious neurocognitive outcomes such as postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), delirium, or dementia [1]. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) occurs commonly after surgery in older adults and seems to be largely transient. Though no universally accepted definition or diagnostic criteria for POCD exists, POCD is characterized by cognitive difficulties including impairment in memory, attention, concentration, and executive function.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is caused by interplay between environmental and genetic risk factors, and it is controversial whether one such environmental factor is the exposure to surgery and anesthesia. Animal studies indicate that surgery and anesthesia contribute to cognitive decline and enhance amyloid beta (Aβ) aggregation and tau hyperphosphorylation [2–5]. Human biomarker investigations reveal that ratios of phosphorylated tau:Aβ in the cerebrospinal fluid convert to an AD pattern postoperatively [6,7], and that surgical patients have increased rates of brain atrophy compared to controls [8]. Despite this evidence, the association between anesthesia, surgery and AD remains unclear. While the apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE4) allele is the strongest genetic risk factor associated with an increased risk of developing late onset AD, no association between APOE genotype and postoperative dementia has been established [9].

We hypothesized that surgery and general anesthesia in older adults is associated with an accelerated rate of decline in cognition, functional status, and brain volumes, and the rate of decline is higher in those with the presence of an APOE4 allele. Using a retrospective cohort design, we tested our hypothesis by interrogating two longstanding aging databases, the Oregon Brain Aging Study (OBAS) and Intelligent Systems for Assessment of Aging Changes (ISAAC) Study.

2. Methods

2.1 Database sources and study population

The study protocols were approved by the institutional review board at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon. All participants provided written informed consent. We conducted a retrospective cohort study using two existing longitudinal natural history studies of cognitive aging: OBAS and ISAAC. OBAS, initiated in 1989 at the NIA/Layton Oregon Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center, is a prospective longitudinal study of a cohort of community-dwelling, functionally independent adults aged 55 years and older [10,11]. Between 1989–2005, 376 participants were evaluated, and 304 participants met inclusion criteria and were enrolled. The attrition rate due to factors other than death was less than 1% per year.

ISAAC is a longitudinal prospective cohort study initiated in 2007, and participants were recruited from the Portland, Oregon, metropolitan area [12]. Briefly, entry criteria for the study required the participant to be a minimum age of 70 years, living independently, non-demented defined as having a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score > 24 and a Clinical Dementia Rating scale score ≤ 0.5, and in average health for age. Individuals with medical conditions that would limit physical participation (e.g. non-ambulatory status) or that were likely to lead to untimely death (such as certain cancers) were excluded.

Each participant underwent an extensive annual assessment including a neuropsychological evaluation, in-depth interview, and a questionnaire regarding new medical events. Between annual assessments, participants were interviewed via telephone approximately every 6 months to update health histories. When applicable, participants’ caregivers also participated in assessments. During these assessments, participants and caregivers were asked to report surgical and anesthetic history. Information recorded included date of operation, type of procedure, and whether the procedure was performed under general anesthesia (GA). In both OBAS and ISAAC, participants’ DNA was banked and apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype was routinely determined. Additionally, OBAS participants underwent annual brain MRI scans.

Using the OBAS (n=304 participants) and ISAAC databases (n=223 participants), we derived a dataset including demographic, outcome, and surgical variables. At study enrollment (time zero), all participants began in the nonsurgical group. Participants were reassigned to the surgical group upon undergoing surgery/GA. Ultimately, the cohort was divided into two groups: the surgical group (n=182) had at least one occurrence of surgery/GA after study enrollment, and the nonsurgical group (n=345) included those who did not have surgery after study enrollment and those who had surgery performed without a general anesthetic. 266 of 304 OBAS participants (88%) had two or more brain MRIs, and 104 of 266 (39%) were exposed to surgery/GA after study enrollment.

2.2 Outcome Measures

Included in the dementia assessment were the MMSE, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), and CDR− Sum of Boxes. The battery of tests used in the neuropsychological analysis assessed multiple cognitive domains, and included: Animal Fluency and Trail Making Test B for executive function, Digit Symbol Test for attention and concentration, and Logical Memory Delayed Recall and Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD (CERAD) Word List Delayed Recall for memory. Functional status was assessed using Basic Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set Functional Activities Questionnaire Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (NACC FAQ). Brain structural MRI measurements included hippocampal volume, white matter hyperintensity (WMH) burden, and ventricular volume which were all normalized according to total intracranial volumes.

2.3 MRI Acquisition

These procedures have been described previously [13]. Briefly, MRI scans were performed with a 1.5 Tesla magnet. The protocol consisted of slice thickness of 4 mm (no gap). The brain was visualized in 2 planes using the following pulse sequences: 1) T1-weighted sagittal images: repetition time (TR) = 600 msec, echo time (TE) = 20 msec; 2) multiecho sequence T2-weighted (TR = 2,800 msec, TE = 80 msec) and proton density (TR = 2,800 msec, TE = 32 msec) coronal images perpendicular to the sagittal plane.

2.4 Image analysis

Image analysts evaluated each scan independently and were blind to subjects’ cognitive and neurologic testing, demographic characteristics, and previous imaging. Image analysis software REGION was used to quantitatively assess regional brain volumes of interest [13,14]. Briefly, recursive regression analysis of bifeature space based on relative tissue intensities was employed to separate tissue types on each coronal image. Pixel areas were summed for all slices and converted to volumetric measures by multiplying by the slice thickness for each of the following regions of interest: total WMH, brain volume, ventricular volume, and hippocampal volumes. Intracranial volume was determined by automatically regressing for brain tissue, CSF, and WMH collectively against bone, creating a boundary along the inner table of the skull. Additional boundaries were manually traced. Hippocampal bodies were manually outlined, as previously described [14]. WMH is distinguished from brain tissue and fluid based on higher signal on both the proton density and T2 images. Median number of MRIs per participant was 4.3 (SD 3.3) assessments.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Mixed-effects models were used to assess the relationship between surgery/GA and rate of change of the described outcome variables. Principal assessment evaluated the rate of change in outcomes for each participant over time. Potential demographic confounders - age, sex, education level, and Cumulative Illness Rating Score (CIRS) - were controlled for in all models as were baseline values of outcomes. CIRS, which rates 13 physiologic systems on a five-point severity scale, is a validated and reliable method commonly used to measure comorbidity in clinical research [15,16, 17]. The key independent variable of interest, exposure to surgery/GA, was modeled as a dichotomous categorical factor (0: no exposure, 1: exposure). Due to the use of two distinct cohorts in this study, OBAS and ISAAC, cohort bias on the time-dependent associations of the outcomes was assessed. Although there were cohort-based population differences in outcomes at entry into the studies, these baseline differences had no bearing on the changes in outcomes over time, which is the principal consideration of the current analysis. Thus, the two cohorts were pooled into a single disposition.

The mixed model allowed for an analysis framework to most appropriately leverage the repeated but varying visits in the OBAS and ISAAC datasets. An unstructured error covariance model was used and parameters were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood procedures. Missing data points in the analytical sample were considered missing at random and the above approach was sufficient under this assumption. Model fit and integrity were examined using a combination of formal fit criteria, including Cook’s distance and the standardized difference of the betas, and visual inspection of the residual plots. Results were considered significant at p<0.05 and included adjusted p-values to correct for statistical tests on multiple response variables using the Holm-Sidak correction. In addition to the listed covariates, APOE genotype was added to the model to investigate its role in moderating the relationship between surgery/GA exposure and the rate of change in outcome measures. An interaction between APOE4 status and anesthesia exposure was the main variable used to evaluate any longitudinal relationship between genetic factors and surgical exposure.

Comparison of log-likelihoods was used to evaluate both the overall goodness-of-fit of the models as well as the informative benefit specific to the inclusion of the principal longitudinal interactions of surgical exposure and APOE4 status. McFadden’s R2 was calculated for the overall fit of a model to a given outcome, with the minimum log-likelihoods for the fully developed models compared to the log-likelihoods from an intercept-only design. The informativeness of the key interactions against the outcomes was assessed using a Chi-square test on the change in log-likelihood of the fully developed models from the nested models without the interactions. This combined approach allowed for a determination not only of the overall fit of the model, but also of the utility specific to the central hypotheses related to anesthesia exposure and APOE4 status.

3. Results

3.1 Study population

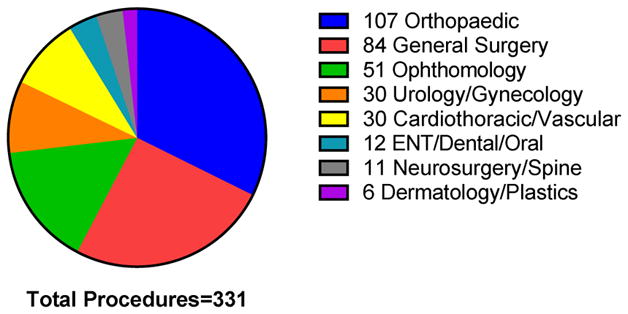

Out of 527 total participants, 182 participants had a combined 331 surgeries under general anesthesia after study enrollment. Participants underwent various surgical procedures (figure 1), with orthopedic surgery being the most common (32.3%). The mean follow-up after study enrollment was 7 years (SD 4.6), and the mean follow-up after surgery/GA was 4.7 years (SD 4). The characteristics of surgical and nonsurgical participants are shown in table 1. There was no difference between the two groups in sex distribution, mean years of education, or APOE4 status. With regard to participant comorbidities, there was no difference between the two groups in CIRS or prevalence of other comorbidities. (Table 1) Interestingly, surgical participants were an average of 3.9 years younger than nonsurgical participants.

Figure 1.

Types of Surgical Procedures.

Participants had a total of 331 surgical procedures under general anesthesia after study enrollment. Examples of general surgery procedures include hernia repairs, bowel resections, and mastectomies. Abbreviation: ENT = Ear, Nose, Throat.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of surgical versus nonsurgical groups of participants during longitudinal study period.

| Surgical (n=182) | Nonsurgical (n=345) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) | 80.0 (SD=7.4) | 83.9 (SD=7.0) | <0.0001 |

| Female (%) | 61% | 68% | 0.10 |

| Mean Education (years) | 15.1 (SD=2.7) | 14.8 (SD=2.7) | 0.33 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale | 20.2 (SD=3.3) | 20.5 (SD=3.5) | 0.56 |

| Presence of an APOE4 allele (%)* | 23% | 22% | 0.68 |

| Obesity (%) | 14% | 15% | 0.81 |

| Diabetes (%) | 10% | 11% | 0.63 |

| Hypertension (%) | 61% | 65% | 0.43 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 1% | 2% | 1.0 |

29 participants missing APOE genotype data

3.2 Associations between surgical exposure and cognitive and functional decline

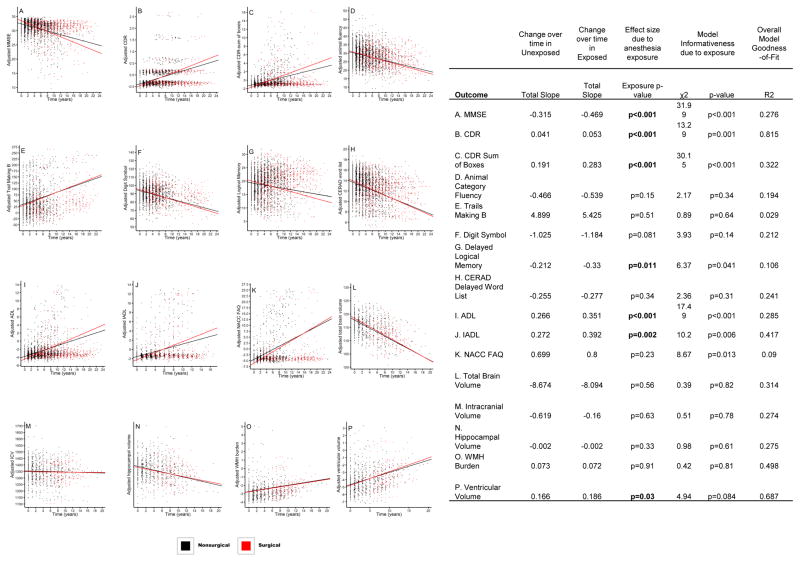

Participants exposed to surgery/GA during the study period experienced a more rapid rate of decline than nonsurgical participants in the following cognitive tests: MMSE (p<0.001), CDR (p<0.001), and CDR− Sum of Boxes (p<0.001).(Figure 2A–C) Similarly, surgical participants experienced a significantly more rapid deterioration in functional status as represented by ADL (p<0.001) and IADL (p=0.002). (Figure 2I&J) Regarding cognitive assessments, Logical Memory Delayed Recall was significantly reduced over time in the surgical compared to the nonsurgical group (p=0.011) while the Digit Symbol Test (p=0.081) and Animal Category Fluency (p=0.15) revealed non-significant trends. (Figure 2G,F,D) There was no difference in rate of decline between the two groups in CERAD Word List Delayed Recall (p=0.34) or the Trails B Time (p=0.51). (Figure 2H&E)

Figure 2.

Rate of change plots in cognitive, functional, and MRI outcomes in surgical and nonsurgical participants over the study period. Time “0” corresponds to study enrollment. Each point represents an individual visit. Abbreviations: ADL = activities of daily living; CDR = clinical dementia rating; CERAD = Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; ICV = intracranial volume; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; NACC FAQ = National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set Functional Activities Questionnaire Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

3.3 Associations between surgical exposure and brain atrophy

When the rate of change of MRI brain measurements were compared, the surgical group had a more rapid increase in ventricular enlargement over time compared to the nonsurgical group (p=0.03, Figure 2P). There were no significant differences in other brain volumes between groups. (Figure 2L–O)

3.4 Surgical exposure in APOE4+ and APOE4− subgroups

Next, the surgical participants were divided into two groups: APOE4+ and APOE4−. Among surgery/GA participants, the APOE4+ participants experienced a more dramatic rate of decline in measures of dementia and functional status compared to APOE4− participants. (Table 2) Specifically, the APOE4+ cohort experienced a more rapid decline than the APOE4− cohort in the following: MMSE (p<0.001), CDR (p=0.018), CDR− Sum of Boxes (p<0.001), ADL (p<0.001) and IADL (p<0.001). APOE4 status did not significantly play a role in the rate of decline in neuropsychological outcomes. In addition, the surgical APOE4+ group had a more rapid increase in ventricular enlargement over time compared to the surgical APOE4− group (p=0.017).

Table 2.

Rate of change in cognitive, functional, and MRI outcomes in surgical APOE4+ versus APOE4− groups.

| Change over time in Surgical APOE4− | Change over time in Surgical APOE4+ | Effect size due to APOE4 status | Model Informativeness due to APOE4 status | Overall Model Goodness-of-Fit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Outcome | Total Slope | Total Slope | Genotype p-value | χ2 | p-value | R2 |

| MMSE | −0.473 | −0.716 | p<0.001 | 15.89 | p<0.001 | 0.267 |

| CDR | 0.058 | 0.077 | p=0.018 | 5.91 | p=0.052 | 0.597 |

| CDR Sum of Boxes | 0.298 | 0.45 | p<0.001 | 15.85 | p<0.001 | 0.289 |

| Animal Category Fluency | −0.587 | −0.62 | p=0.73 | 0.13 | p=0.94 | 0.2 |

| Trails Making B | 6.731 | 7.958 | p=0.41 | 1.47 | p=0.48 | 0.033 |

| Digit Symbol | −1.372 | −1.411 | p=0.81 | 4.27 | p=0.12 | 0.207 |

| Delayed Logical Memory | −0.313 | −0.404 | p=0.28 | 1.96 | p=0.38 | 0.088 |

| CERAD Delayed Word List | −0.342 | −0.347 | p=0.91 | 0.02 | p=0.99 | 0.251 |

| ADL | 0.297 | 0.467 | p<0.001 | 23.56 | p<0.001 | 0.311 |

| IADL | 0.426 | 0.771 | p<0.001 | 15.74 | p<0.001 | 0.409 |

| NACC FAQ | 0.792 | 0.993 | p=0.09 | 3.07 | p=0.22 | 0.115 |

| Total Brain Volume | −9.831 | −8.392 | p=0.37 | 1.95 | p=0.38 | 0.397 |

| Intracranial Volume | −0.843 | −0.794 | p=0.13 | 7.51 | p=0.023 | 0.352 |

| Hippocampal Volume | −0.002 | −0.001 | p=0.36 | 2.71 | p=0.26 | 0.3 |

| WMH Burden | 0.046 | 0.016 | p=0.5 | 0.48 | p=0.79 | 0.422 |

| Ventricular Volume | 0.161 | 0.278 | p=0.017 | 6.51 | p=0.039 | 0.656 |

3.5 Synergistic effects of surgical exposure and APOE4+ status

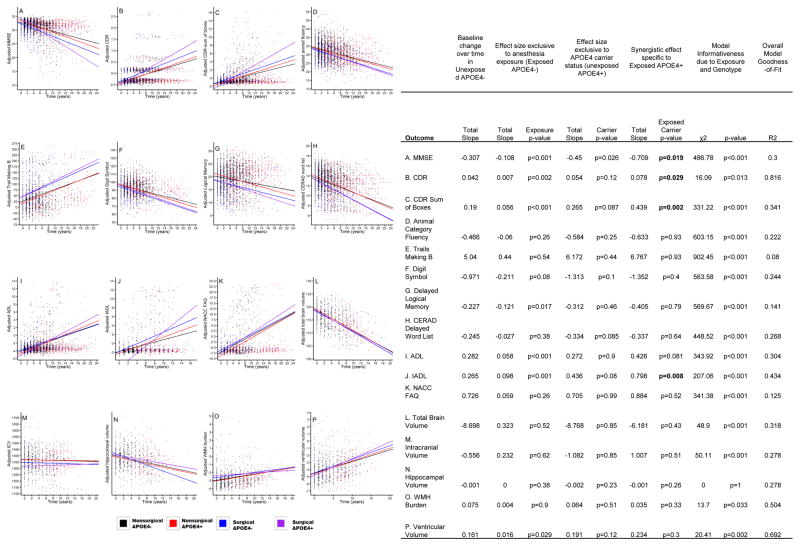

Finally, the interaction between surgery/GA exposure and APOE4+ status was the main variable used to determine their synergistic effect on the rate of change of the listed outcome variables. As portrayed in figure 3, this revealed significant increases in the rate of change in the following outcomes: MMSE (p=0.019, Figure 3A), CDR (p=0.029, Figure 3B), CDR-Sum of boxes (p=0.002, Figure 3C), and IADL (p=0.008, Figure 3J).

Figure 3.

Rate of change plots of cognitive, functional, and MRI outcomes. These plots represent the synergistic effect of exposure to general anesthesia/surgery combined with APOE4+ status (purple). Time “0” corresponds to study enrollment. Each point represents an individual visit. Abbreviations: ADL = activities of daily living; CDR = clinical dementia rating; CERAD = Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; ICV = intracranial volume; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; NACC FAQ = National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set Functional Activities Questionnaire Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

4. Discussion

This cohort study demonstrates that surgery and general anesthesia in older adults is associated with an accelerated rate of decline in cognitive and functional status as well as a more dramatic increase in ventricular size. Also, we found that exposure to surgery/GA and the presence of an APOE4 allele had a synergistic effect on the acceleration of the rate of deterioration in cognition, function, and ventricular size.

Our data support large, retrospective cohort studies that found the risk of developing dementia was higher in patients undergoing surgery and anesthesia when compared to control groups [18,19]. However, there remains inconsistency in clinical studies as to whether surgery and/or anesthesia have an effect on the age of onset or progression of dementia, and the two most recent population-based case-control studies had conflicting results [20,21]. Recently, Liu et al conducted the only prospective randomized study to date investigating the association between anesthesia, surgery, and dementia [22]. In a study of 180 participants with amnestic mild cognitive impairment, the authors concluded that inhaled sevoflurane, but not intravenous propofol or epidural lidocaine anesthesia, accelerated the progression of cognitive decline following lumbar spine surgery. One factor that might contribute to the current inconsistency in the literature is the variability in study populations. The majority of clinical studies to date have not been enriched with participants known to be particularly vulnerable to deleterious postoperative neurocognitive syndromes. In order to adequately address this issue, vulnerable populations, by virtue of either phenotype, genotype, or shared environmental predictors must be defined and matched. Enriching study populations by including older adults that have decreased preoperative cognitive capacity, express AD biomarkers, or possess genetic risk factors (i.e. APOE4) will allow us to begin to shed light on whether there are specific anesthetic or surgical variables associated with an increased risk of postoperative cognitive decline.

Our data, which demonstrate an increase in the rate of ventricular enlargement following surgery/GA, support evidence from a 2012 study using the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) data in which surgical patients had increased rates of cortical gray matter and hippocampal atrophy and lateral ventricular enlargement 5–9 months postoperatively compared to nonsurgical controls[8]. Though the rate of ventricular enlargement was the only significant difference we observed in our surgical versus nonsurgical groups, previous work by ADNI demonstrated that the rate of ventricular enlargement over time was a valid measure of AD progression[23].

While we observed a significant association between surgery/GA and the rate of decline in memory indices, no significant association between exposure to anesthesia and surgery and the rate of decline in executive function was observed. These data support POCD studies where despite an equal distribution of cognitive impairment in executive function and memory at hospital discharge, by 3 months postoperatively many more participants were impaired in measures of memory than executive function[24]. Finally, we found that among the surgical participants, the rate of deterioration in cognition, function, and ventricular size was more pronounced in participants with at least one APOE4 allele. A recent meta-analysis did not find a correlation between APOE genotype and incidence of POCD[25]. However, this meta-analysis excluded studies in which participants had preexisting cognitive impairment prior to surgery, and the majority of included studies had a follow-up period of 3-months or less[25]. In the current investigation, participants were followed for an average of 7 years after study enrollment, and cognitive testing was not performed in-phase with surgery. Additionally, we took the analysis one step further and found that the interaction between exposure to surgery/GA and APOE4+ status synergistically accelerated the decline in MMSE, CDR, CDR Sum of Boxes, and IADL.

The limitations of the study include those limitations inherent to a retrospective design. However, although we analyzed the data in a retrospective manner, both OBAS and ISAAC are prospective, longitudinal cohort studies. Next, participants’ exposures to anesthesia and surgery were obtained by reports from the participants or their caregivers. Though participants are interviewed twice annually, there are limitations to self-reported information in a population of aging individuals. Further, the limited availability of detailed surgical/anesthetic records prevented us from using more complex stratifications based on duration of anesthesia, particular anesthetic agents, etc. Another potential limitation is that the separation of the cohort into two groups based on surgical/GA exposure may not be as robust as if we had matched cases and controls. In other words, participants undergoing surgery/GA might be fundamentally different from those who did not. We attempted to decrease this confounder by adjusting for age, sex, education level, and CIRS in the data analysis. Further, our surgical and nonsurgical groups did not significantly differ in the rate of hypertension, obesity, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia. Finally, our surgical group was actually slightly younger than our nonsurgical group (average 3.9 years). Additionally, a strength of our analysis is the fact that participants were followed for several years. Because of the long-term follow-up, it is less likely that acute conditions would have major effects on the results.

In summary, these data add to the growing body of evidence linking exposure to surgery and anesthesia and resultant cognitive decline and dementia. This study is among the first to show an association of surgery and anesthesia and structural brain atrophy. Alzheimer’s results as some combination of genetic and environmental factors. Whether surgery and anesthesia qualify as one of these factors must be confirmed. In the meantime, studies investigating the role of anesthesia/surgery in postoperative cognitive decline should include potentially vulnerable populations such as those with preexisting cognitive decline, APOE4 genotype, and older adults.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic Review

We reviewed the literature using PubMed for studies related to surgical/anesthetic exposure and dementia. We examined retrospective and prospective work as well as biomarker investigations.

Interpretation

The majority of longitudinal aging studies do not collect information regarding surgical/anesthetic exposures. In the OBAS and ISAAC cohorts, participants exposed to surgery/general anesthesia experienced an accelerated rate of cognitive and functional decline as well as more rapid ventricular enlargement. This is one of the first studies to show a correlation between surgical/anesthetic exposure and ventricular enlargement. Further, surgical/anesthetic exposure in addition to an APOE4 allele had a synergistic effect on resultant cognitive and functional decline.

Future Directions

It is important for longitudinal aging studies to collect information regarding participants’ surgical/anesthetic exposures. In the future, investigators should enrich study popuxlations to include participants at higher risk for postoperative cognitive dysfunction by virtue of age or genetic factors (i.e. APOE4).

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality-funded BIRCWH K12 award (K12 HD 043488) and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P30AG024978, R01AG024059, P30AG008017, 1U10NS077350-01, R01AG036772, R01AG043398) and a Merit Review Grant from the Department of Veteran’s Affairs. The authors would like to thank Kirk Hogan, MD, JD, for reviewing drafts of the manuscript.

Role of the funding source: The funding sources had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Charles F. Murchison, Email: murchiso@ohsu.edu.

Nora C. Mattek, Email: mattekn@ohsu.edu.

Lisa C. Silbert, Email: silbertl@ohsu.edu.

Jeffrey A. Kaye, Email: kaye@ohsu.edu.

Joseph F. Quinn, Email: quinnj@ohsu.edu.

References

- 1.Eckenhoff RG, Laudansky KF. Anesthesia, surgery, illness and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;47:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie Z, Dong Y, Maeda U, Moir RD, Xia W, Culley DJ, et al. The inhalation anesthetic isoflurane induces a vicious cycle of apoptosis and amyloid beta-protein accumulation. J Neurosci. 2007;27(6):1247–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5320-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H, Weng H. Up-regulation of Alzheimer’s disease-associated proteins may cause enflurane anesthesia induced cognitive decline in aged rats. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(2):185–9. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1474-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Planel E, Richter KE, Nolan CE, Finley JE, Liu L, Wen Y, et al. Anesthesia leads to tau hyperphosphorylation through inhibition of phosphatase activity by hypothermia. J Neurosci. 2007;27(12):3090–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4854-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fodale V, Santamaria LB, Schifilliti D, Mandal PK. Anaesthetics and postoperative cognitive dysfunction: a pathological mechanism mimicking Alzheimer’s disease. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(4):388–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palotas A, Reis HJ, Bogats G, Babik B, Racsmany M, Engvau L, et al. Coronary artery bypass surgery provokes Alzheimer’s disease-like changes in the cerebrospinal fluid. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(4):1153–64. doi: 10.3233/jad-2010-100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang JX, Baranov D, Hammond M, Shaw LM, Eckenhoff MF, Eckenhoff RG. Human Alzheimer and Inflammation Biomarkers after Anesthesia and Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;115(4):727–732. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822e9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kline RP, Pirraglia E, Cheng H, De Santi S, Li Y, Haile M, et al. Surgery and brain atrophy in cognitively normal elderly subjects and subjects diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(3):603–12. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318246ec0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogan KJ. Hereditary vulnerabilities to post-operative cognitive dysfunction and dementia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howieson DB, Holm LA, Kaye JA, Oken BS, Howieson J. Neurologic function in the optimally healthy oldest old. Neuropsychological evaluation Neurology. 1993;43(10):1882–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.10.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howieson DB, Camicioli R, Quinn J, Silbert LC, Care B, Moore MM, et al. Natural history of cognitive decline in the old old. Neurology. 2003;60(9):1489–94. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063317.44167.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaye JA, Maxwell SA, Mattek N, Hayes TL, Dodge H, Pavel M, et al. Intelligent Systems For Assessing Aging Changes: home-based, unobtrusive, and continuous assessment of aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(Suppl 1):i180–90. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller EA, Moore MM, Kerr DC, Sexton G, Camicioli RM, Howieson DB, et al. Brain volume preserved in healthy elderly through the eleventh decade. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1555–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaye JA, Swihart T, Howieson D, Dame A, Moore MM, Karnos T, et al. Volume loss of the hippocampus and temporal lobe in healthy elderly persons destined to develop dementia. Neurology. 1997;48(5):1297–304. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. How to measure comorbidity. a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(3):221–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00585-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parmelee PA, Thuras PD, Katz IR, Lawton MP. Validation of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale in a geriatric residential population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(2):130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16(5):622–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee TA, Wolozin B, Weiss KB, Bednar MM. Assessment of the emergence of Alzheimer’s disease following coronary artery bypass graft surgery or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7(4):319–24. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen PL, Yang CW, Tseng YK, Sun WZ, Wang JL, Wang SJ, et al. Risk of dementia after anaesthesia and surgery. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(3):188–93. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sprung J, Jankowski CJ, Roberts RO, Weingarten TN, Aguilar AL, Runkle KJ, et al. Anesthesia and Incident Dementia: A Population-Based, Nested, Case-Control Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(6):552–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CW, Lin CC, Chen KB, Kuo YC, Li CY, Chung CJ. Increased risk of dementia in people with previous exposure to general anesthesia: a nationwide population-based case-control study. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(2):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.05.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Pan N, Ma Y, Zhang S, Guo W, Li H, et al. Inhaled Sevoflurane May Promote Progression of Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345(5):355–360. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31825a674d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nestor SM, Rupsingh R, Borrie M, Smith M, Accomazzi V, Wells JL, et al. Ventricular enlargement as a possible measure of Alzheimer’s disease progression validated using the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative database. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 9):2443–54. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price CC, Garvan CW, Monk TG. Type and severity of cognitive decline in older adults after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(1):8–17. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000296072.02527.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao L, Wang K, Gu T, Du B, Song J. Association between APOE epsilon 4 allele and postoperative cognitive dysfunction: a meta-analysis. Int J Neurosci. 2014;124(7):478–85. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2013.860601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]