Introduction

Adolescent substance use is associated with short- and long-term negative outcomes including risky sexual behavior (Palen, Smith, Flisher, Caldwell, & Mpofu, 2006), school dropout (Townsend, Flisher, & King, 2007), future substance use/abuse (Grant et al., 2006), and injury, violence, and suicide (Bauman & Phongsavan, 1999). Although reducing adolescent substance use is a goal of many countries, it is especially critical in South Africa, a developing nation with an increasing adolescent substance use problem (Pasche & Myers, 2012; Wegner, Flisher, Muller, & Lombard, 2006).

It is well understood that not all adolescents follow the same pattern of substance use initiation and development (Tucker, Ellickson, Orlando, Martino, & Klein, 2005). To address this, previous studies have made use of person-centered approaches to model heterogeneity of use over time. In general, trajectory classes separate into stable, escalating, and decreasing user groups. For example, stable groups may include those who have never used (Flory, Lynam, Milich, Leukefeld, & Clayton, 2004) or have consistent levels of use (e.g., low; Chassin, Pitts, & Prost, 2002). Escalating groups may include those that begin at a higher initial level and increase over time (e.g., early-heavy) or that have a lower initial level of use and also increase over time (e.g., late-heavy; Flory et al.). Decreasing groups include those that have a high initial level of use and then decrease over time (Schulenberg, O'Malley, Bachman, Wadsworth, & Johnston, 1996). Although these person-centered studies have elucidated subgroups of substance use and predictors of development, little is known about this topic within South Africa. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to provide insight into substance use trajectories among South African adolescents using a person-centered approach. Better understanding how substance use develops is an important first step which allows for further investigation into low- versus high-level and escalating versus stable patterns of substance use.

The secondary purpose of this study took a prevention approach to understanding how leisure may influence developmental trajectory groups identified from the first aim. There are a number of substance use prevention programs that have promising evidence in the US, but these programs are largely lacking in the South African context. The HealthWise South Africa: Life Skills for Young Adults (HW) intervention is one program that targets both substance use and sexual risk with promising results (Smith et al., 2008). One reason it may have been successful is it uniquely targets aspects of leisure behavior and experience and educates adolescents on how to engage in healthy, meaningful activities during their free time. Among other things, HW teaches youth leisure skills such as constraint negotiation and the ability to restructure unhealthy leisure pursuits into healthy ones (Caldwell et al., 2004). These lessons target aspects of leisure associated with risk (e.g., boredom; Wegner et al., 2006; Weybright, Caldwell, Ram, Smith, & Wegner, 2015) and protection (e.g., participation in healthy leisure activities, Weybright, Caldwell, Ram, Smith, & Jacobs, 2014). Taken together, the HW program teaches skills toward and encourages youth to participate in healthy leisure. By analyzing how substance use trajectories are differentially related to healthy leisure, we can determine which trajectory class may benefit the most from a prevention program targeting leisure.

South African Adolescent Substance Use

In South Africa, adolescent substance use is a public health concern. Students in Grades 8 through 11 in the Western Cape, South Africa reported past month substance use rates of 31% for alcohol, 27% for tobacco, and 7% for marijuana, with increasing rates of use between Grade 8 and Grade 11 (except for Black1 females; Flisher, Parry, Evans, Muller, & Lombard, 2003). The most recent South African Youth Risk Behavior Survey (SAYRBS; Reddy et al., 2010) conducted in 2008 suggested even higher levels of use for adolescents within the Western Cape than previously reported, and are the highest within the country. The 2008 survey found past month alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana rates of 53%, 37%, and 16% respectively. South African and US adolescents demonstrate similar patterns of substance use initiation, trying alcohol or tobacco first, followed by marijuana and inhalants. However, South African adolescents transition through substances at a faster rate than their US counterparts (Patrick et al., 2009).

Benefits of Person-Centered Approaches

The pattern of substance use initiation and development is not well established among South African adolescents. Some may abstain while others engage in substance use at a young age and continue to increase use over time. Since we are aware of heterogeneity within developmental trajectories of substance use, using methodological tools capturing individual change, such as person-centered approaches, provides a richer understanding of substance use development. Unlike traditional variable-centered, person-centered approaches acknowledge the heterogeneity in the population, and identify latent subgroups who follow different developmental trajectories, in our case, developmental trajectories of adolescent substance use.

Connell, Dishion, and Deater-Deckard (2006) emphasized the need to identify and understand these trajectory subgroups and suggested when substance using adolescents “are not distinguished from the rest of the sample, we run the risk of overemphasizing risk dynamics among youth who are otherwise on a normative developmental trajectory” (pp. 424-425). Identifying trajectory development may be even more urgent in developing countries such as South Africa given the increased context of risk (e.g., high incidence of HIV/AIDS, prevalence of poverty, lack of healthy leisure opportunities) and where there is only a crude understanding of how substance use develops over time.

Few studies addressing substance use have taken a person-centered approach within the South African context. Patrick and colleagues (2009) used latent transition analysis to identify patterns of substance use onset, finding South African adolescents follow a similar progression of initiation to their US peers where alcohol or tobacco is tried first, followed by both alcohol and tobacco, then marijuana, and finally inhalants. Palen, Smith, Caldwell, and Flisher (2008) and Tibbits, Caldwell, Smith, and Wegner (2009) both used latent class analysis with covariates. Palen and colleagues identified three longitudinal patterns of female cigarette use: non-smokers, initiators, and consistent smokers. As compared to non-smokers, initiators and consistent smokers were more likely to have academic difficulties, spend time with pro-smoking peers, and also use alcohol or marijuana. Tibbits and colleagues found past month use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana was associated with leisure profiles in both males and females. Unexpectedly, males in the ‘Uninvolved’ leisure profile (characterized by watching TV or movies) were less likely to use substances than all other leisure profiles (Sports and Volunteer, Mixed, Recreation and Hobbies, Mixed, Artistic, and Highly Involved). Although these studies serve to inform our understanding of profiles of substance use in South Africa, none have identified substance use trajectories in adolescents.

Role of Leisure in Adolescent Substance Use

Leisure refers to time that is unobligated such as that outside of school or work, and is often referred to as free-time. The opportunities leisure presents for both risk and development are multi-faceted (Zaslow & Takanishi, 1993) and regardless of where an adolescent lives, contextual factors are important. For example, neighborhood attributes (e.g., access to and availability of community parks) and opportunities for structured, supervised activities with a caring, supportive adult are associated with health promotion and healthy development (Osgood & Anderson, 2006; Witt & Caldwell, 2010). Adolescents who are not afforded these opportunities are more likely to engage in risk behavior. Within the Cape Town area of South Africa, where current study data were collected, adolescents report having fewer leisure and recreation opportunities within their community, a lack of adult supervision, and too much free time (Wegner, 2011). Wegner concluded this impoverished, understimulating environment contributed to substance use within the sample.

Although some leisure concepts have been previously addressed (e.g., leisure motivation, Caldwell, Patrick, Smith, Palen, & Wegner, 2010; Palen, Caldwell, Smith, Gleeson, & Patrick, 2011; leisure constraints, Palen et al., 2010; activity participation, Tibbits et al., 2009), others are not well understood and lack empirical support, especially within developing contexts. There is a need to better elucidate the impact of leisure experience, including healthy leisure, in a prevention setting to inform interventions targeting substance use.

Healthy leisure is a new concept within both leisure and developmental research. Although there is no consistent conceptualization, it typically refers to free time used in a positive, meaningful way. Conceptualization of healthy leisure in the current study was guided by previous work (e.g., Sharp et al., 2011; Weybright et al., 2014), the Leisure Activities-Context-Experience model (Caldwell, 2011), and Problem Behavior Theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Collectively, these models provide a broad ecological framework for understanding the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental factors that may contribute to or detract from leisure experience.

Although there are numerous references to healthy leisure in the popular literature, only two studies (Sharp et al., 2011; Weybright et al., 2014) to date have explicitly measured this construct and its association with adolescent risk behavior. Although both of these studies were part of the larger project from which the data in the current study emanated, the current study builds off of each of these two studies and extends them in multiple conceptual and methodological ways.

Sharp and colleagues (2011) found higher levels of healthy leisure at baseline were associated with a decreased likelihood of using alcohol and marijuana, and as healthy leisure increased over time, the likelihood of using alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana decreased. Although this approach does allow for examination of within-person effects, it does not capture substance use trajectory subgroups over time and did not account for other substances such as methamphetamine and inhalants. In addition, Sharp et al.'s analyses were limited to four items to measure healthy leisure rather than the process used in the current study of conducting a factor analysis to more fully account for healthy leisure attributes, which was also used in Weybright et al. (2014). Weybright and colleagues conceptualized healthy leisure as a trait (i.e., average across all time points) and state (i.e., difference between average and each time point) to determine the association with overall substance use. Results indicated lower levels of trait and state subjective healthy leisure were associated with higher levels of substance use while there was no significant association with the leisure planning efficacy factor.

In addition to the differences already identified, the current study is differentiated from the Sharp et al. (2011) and Weybright et al. (2014) studies in that, first, data in this paper are limited to control group participants in three cohorts across eight waves of data who have a history of substance use as compared to control participants in one cohort across seven waves of data in Sharp et al. and control and treatment participants in Weybright et al. Second, the current study examines trajectories of substance use over time rather than associations with substance use at each time point. Given that there are limited data available on trajectories of substance use in developing contexts, especially for illicit substances, the current study's main contribution is identification of multiple substance use trajectories with a secondary contribution of beginning to understand how trajectories are differentially associated with leisure experience.

Leisure Activities-Context-Experience Model

Caldwell's (2011) Leisure Activities-Context-Experience model (LACE) provides a comprehensive lens through which to view the distinct elements of leisure experience, their interrelationships, and how these elements contribute to healthy or risky behavior. The LACE model suggests that in order to better understand the mechanisms of how leisure and risk behavior intersect, researchers must understand not only what adolescents are doing (activities and time use), but also the contextual elements (e.g., opportunities for leadership or whether adults are present) including how adolescents are actually experiencing the activity (e.g., boredom, excitement, loneliness). For example, one general finding is that unstructured, unsupervised time spent with peers is associated with risk behavior such as substance use and delinquency in adolescence (e.g., Lee & Vandell, 2015; Osgood & Anderson, 2006). Such information is reflected in the ‘activities and time use’ element of the LACE model. However, Caldwell (2011) notes that general time use, while an important starting point, provides only a limited amount of information.

Problem Behavior Theory

From a theoretical standpoint, Problem Behavior Theory (PBT; Jessor & Jessor, 1977) and its recent extension to health behavior was used to understand the relationship between healthy leisure and differing substance use trajectories. PBT is a social psychological framework where interactions between intrapersonal (e.g., personality, expectations), environmental (e.g., social context, peer approval), and behavioral systems (e.g., conventional vs. problem behavior structures) serve to facilitate or inhibit risk behavior. Jessor (2008) extended PBT to focus on health behaviors suggesting the interactions that served to explain problem behaviors (i.e., health compromising behaviors) also explained health-enhancing behaviors (e.g., diet, exercise).

When health-enhancing behaviors are viewed as socially normative and supported by society, institutions, parents, and peers, adolescents are encouraged to adopt them (Donovan, Jessor, & Costa, 1991). Within the South African context, adolescents report perceptions of parental, educator, and peer disapproval of substance use (Morojele, Brook, Kachieng'a, 2006) however, the normative perceptions of healthy leisure are not understood. From a conceptual standpoint, Donovan, Jessor, and Costa (1993) found engagement in health-enhancing behaviors (e.g., sleep, diet, exercise) to all correlate, although modestly, with one latent factor, indicative of a health-focused lifestyle rather than disparate behaviors. Similarly, we view healthy leisure as an additional facet of a health-focused lifestyle and therefore part of the health-enhancing orientation.

Empirical applications support PBT's extension to the health behavior domain and specifically to address substance use. Results indicate greater involvement in risk behavior, including substance use, was associated with lower levels of engagement in healthy behaviors or a healthy leisure lifestyle (e.g., value on health, health self-description; Donovan et al., 1991). Studies addressing leisure experience suggest a similar negative relationship between substance use and health behaviors such as physical activity and sport participation in youth (Kaczynski, Mannell, & Manske, 2008). Two prior studies, the only to directly measure healthy leisure, identified a negative association between subjective perceptions of healthy leisure and substance use within a South African adolescent sample; demonstrating cross-cultural application and collectively, supported PBT's extension to health-enhancing behaviors (Sharp et al., 2011; Weybright et al., 2014). Within the current study, we anticipated a negative relationship between health-enhancing and health-compromising behaviors such that individuals with less extreme substance use trajectory patterns (e.g., lower initial levels of use, shallower trajectories over time) would be associated with higher levels of healthy leisure.

Research Questions

This study takes a person-centered approach to understanding the connection between healthy leisure and the development of substance use. To address this connection, two research questions were examined: (1) what are the distinctive developmental trajectories of South African adolescent substance use and (2) what is the influence of healthy leisure on these trajectories?

To address these questions, growth mixture models (GMM) were used to identify latent classes of substance use trajectories within South African adolescents. GMMs identified differing developmental paths and were used to examine and account for inter-individual differences in intra-individual change (Ram & Grimm, 2009). Identifying developmental trajectories is central to understanding how adolescents change over time and by identifying clusters of developmental trajectories, the unobserved heterogeneity within the sample is modeled. Once developmental trajectories of substance use were identified, the influence of healthy leisure on each sub-group was determined. Based on PBT, we expected classes with more extreme trajectories of substance use would be associated with lower levels of healthy leisure and conversely, classes with low levels of substance use associated with higher levels of healthy leisure.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The current sample includes students from five control group schools in Mitchell's Plain, a low-income township approximately 15 miles outside of Cape Town, South Africa, who participated in an effectiveness trial of HealthWise South Africa, a school-based life skills curriculum intervention addressing adolescent health risk behavior (see Caldwell et al., 2004). Additional information on the overall study and full sample can be found elsewhere (Smith et al., 2008). To facilitate the process of identifying trajectories of substance use, students indicating no lifetime use across all measurement occasions (n = 498) were excluded from analyses. When comparing lifetime non-users to users, there were no differences in age (Mnon-user=13.8; Muser=13.9; t(2745)=-0.81, p=.42), gender (χ2(1)=0.49, p=.48), or race (χ2(4)=8.21, p=.08). The final analysis sample (N=2.249) was 53% female, mostly Coloured (93%), and 13.9 years old on average at Wave 1 (SD=0.72; range 12-18 years old). Indicators of socio-economic status were stable across the sample including having electricity in the home (99%), running water in the home (94%), and living in a brick house (87%). This homogeneity likely is due to the history of forced relocation based on the Group Areas Act during Apartheid resulting in relatively racially and socioeconomically segregated geographical zones. Related to religion, 42% identified as Christian-Other while 31% identified as Islamic and 25% as Christian-Catholic.

The study and its passive parental consent and adolescent assent procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at study-affiliated universities and by school administrators. Students were followed longitudinally in three cohorts starting in 8th Grade and data was collected bi-annually, once per semester. Cohort 1 was followed from 8th through 11th Grade between March 2004 and October 2007. Cohort 2 was followed from 8th to 10th Grade between March 2005 and October 2007. Cohort 3 was followed from 8th to 10th Grade between March 2006 and March 2008. Prior work with these data found that the cohorts did not differ from one another (e.g., Tibbits, Smith, Caldwell, & Flisher, 2011; Weybright et al., 2015), so all cohorts were pooled together in the current study.

Measures

Substance use

Overall substance use at each assessment was quantified using a composite index intended to reflect both the range of substances used as well as the recency, frequency, and level of use. The current study accounted for five substances including alcohol, tobacco, methamphetamines, marijuana, and inhalants. The approach of using a composite score was based on two factors. First, we were preliminarily interested in trajectories of overall substance use over time and less concerned with growth of individual substances at this point in time. Second, due to the low prevalence of methamphetamine and inhalant use and the use of a person-centered approach, creating a composite score was the only way to ensure sufficient power to analyze these two substances.

Using a selection of items available at each assessment, indications of use of each substance were indexed along a 4-point scale. For example, alcoholic drinks was reported using three items capturing lifetime use “How many drinks of alcohol (including beer and wine) have you had in your entire life?”, past month use “During the last four weeks did you use alcohol (including beer and wine)?” and intensity of past month use “During the past four weeks how many alcoholic drinks did you have?”. This information was then indexed as follows, where 1 = lifetime use but no past month use, 2 = lifetime use and one or fewer drinks in the past month, 3 = lifetime use and two to three drinks in the past month, and 4 = lifetime use and four or more drinks in the past month. The five indices were then summed together to obtain a substance use composite that could range from 0 to 20.

Healthy leisure

As described in detail in previous reports (Weybright et al., 2014) measures of healthy leisure were created from existing items. In brief, 15 candidate items (responses on a 0= strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree scale) were pooled and examined for a cohesive structure in the full data sample using exploratory factor analysis with promax rotation. Factors were positively correlated at 0.63. Two factors emerged: a healthy leisure factor that was indicated by four items (α=.77) asking about subjective perceptions of healthy leisure, “I get a lot of benefits (good things) out of my free time activities,” “The things that I do in my free time are healthy,” “I feel good about myself in my free time,” and “Having healthy free time activities can help me avoid risky behavior.”; and a leisure planning efficacy factor indicated by four items (α=.76) referencing individuals' ability to plan free time activities, “I am confident I can plan activities for myself without help from my parents,” “I know how to plan my free time activities,” “I make good decisions about what to do in my free time,” and “I know how to get the information needed to make the best choice of what to do in my free time.” Based on the factor analysis, healthy leisure and leisure planning efficacy scores were calculated at each assessment as the average of relevant items. Due to the lack of variability over time in each scaled factor (see Table 1), items were aggregated across waves, with higher scores indicating healthier and more efficacious planning in leisure.

Table 1. Sample Descriptives for Substance Use, Healthy Leisure, and Leisure Planning Efficacy.

| Variable | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | Grade 11 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beg. n=2.249 | End n=2.148 | Beg. n=2.106 | End n=2.005 | Beg. n=1.757 | End n=1.155 | Beg. n=594 | End n=453 | |

| Substance Use Composite | 1.52 (2.36) | 2.24 (2.91) | 2.83 (3.32) | 3.70 (3.74) | 4.18 (3.86) | 4.34 (3.85) | 4.75 (3.88) | 4.43 (3.78) |

| Healthy Leisure | 2.86 (0.81) | 2.86 (0.79) | 2.82 (0.82) | 2.82 (0.78) | 2.78 (0.80) | 2.79 (0.78) | 2.87 (0.73) | 2.79 (0.76) |

| Leisure Planning Efficacy | 2.84 (0.79) | 2.80 (0.79) | 2.79 (0.83) | 2.82 (0.80) | 2.79 (0.80) | 2.74 (0.81) | 2.86 (0.78) | 2.82 (0.76) |

Note: Sample means and (standard deviations). Measures were collected at the beginning and end of Grades 8 through 11 occurring in October and March respectively. Substance Use composite ranged from 0-20. Leisure factors ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

Analytic Plan and Preliminary Steps

Our analytic tasks were to identify distinctive developmental trajectories of South African adolescent substance use, and examine if and how healthy leisure was related to those trajectories. Trajectories were identified using growth mixture models (GMM), following the procedures outlined by Ram and Grimm (2009). Covering previous work that has identified anywhere from 3 to 6 classes with distinct substance use trajectories (Colder, Campbell, Ruel, Richardson, & Flay, 2002; Chassin, Flora, & King, 2004), we specified a series of GMMs with between 2 and 8 classes with different substance use trajectories. Models of the Poisson distributed outcome were of standard linear form, with allowance for group differences in mean intercept (g0), located at beginning of 8th Grade (as early in the developmental process as possible with these data), and mean slope (g1) with variances set to zero. Given the Poisson distribution of the substance use variable, and prior knowledge that there was a subgroup of minimal users, models were specified so that they included a low-use class with no variance in slope. Following typical procedures, the best fitting of these models was selected through systematic evaluation of parameter estimates, fit information criteria (e.g., AIC, BIC), entropy, and likelihood ratio tests (Ram & Grimm, 2009). Once an acceptable model of the latent class differences was identified, class-level trajectories were plotted, named, and examined with respect to demographics and healthy leisure. Specifically, the healthy leisure and leisure planning efficacy variables were added as ‘auxiliary’ predictors of class membership in what is effectively a logistic regression framework (i.e., odds of belonging to a specific class relative to a reference class). Follow-up analyses (i.e., ANOVA and chi-square tests) where individuals were assigned to a class based on their highest posterior probability of class membership were used to identify group differences in gender, age, proxy for socio-economic status (i.e., family owning a motor car), and religion. Additional contextual variables were considered, but due to homogeneity within the geographical area where data were collected (e.g., access to recreation facilities), were not informative. Models were implemented using Mplus 6.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2005) with missing data handled using full information maximum likelihood (Graham, 2009). Follow-up analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.3.

Results

Substance Use Development

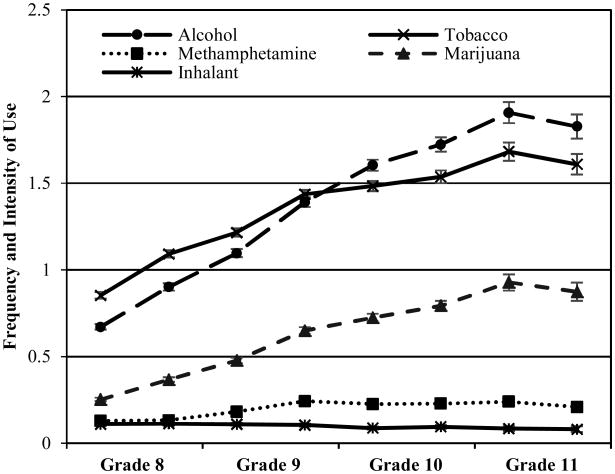

The average prevalence of use for each substance are shown in Figure 1, along with the sample-level descriptives for substance use composite and leisure repeated measures in Table 1. As can be noted, mean levels of substance use generally increased across time, starting at 1.52 in beginning of 8th Grade and reaching up to 4.75 in the beginning of 11th Grade. GMMs with between 2 and 8 classes were examined as potential representations of the between-person differences in the substance use trajectories. Solutions with between two and five classes all had significant LRTs indicating that each solution was preferable to a solution with one fewer classes. Solutions with six or more classes were eliminated from further consideration due to non-significant LRTs indicating a solution with one fewer classes was preferable. Fit information criteria (see Table 2) suggested that the four (AIC = 52 990, BIC = 53 041) and five class (AIC = 52 335, BIC = 52 403) solutions provided better fit than the two (AIC = 56 102, BIC = 56 130) and three (AIC = 54 131, BIC = 54 165) class solutions, with entropy slightly higher in the four (.777) than in the five class solution (.772). In plotting and examining the solutions for practical interpretability, we noted that two classes within the five class solution were very similar and posed no differential practical implications. We thus concluded that, of the range of models examined, the four class solution provided the most viable representation of distinct substance use trajectories.

Figure 1.

Average frequency and intensity of use of each substance (means and standard errors).

Table 2. Model Fit of All Growth Mixture Models.

| Number of Classes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 + Predictors | |

| Class Size | (N=2.148) | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Nc=1 | 1.235 | 866 | 813 | 689 | 648 | 599 | 463 | 786 |

| Nc=2 | 1.014 | 802 | 643 | 655 | 535 | 447 | 458 | 607 |

| Nc=3 | ----- | 581 | 447 | 499 | 471 | 447 | 409 | 418 |

| Nc=4 | ----- | ----- | 346 | 208 | 278 | 274 | 283 | 337 |

| Nc=5 | ----- | ----- | ----- | 198 | 167 | 170 | 219 | ----- |

| Nc=6 | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 150 | 158 | 169 | ----- |

| Nc=7 | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 154 | 146 | ----- |

| Nc=8 | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 102 | ----- |

|

| ||||||||

| Fit Criteria | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| AIC | 56 102 | 54 131 | 52 990 | 52 335 | 52 075 | 51 614 | 51 401 | 50 819 |

| BIC | 56 130 | 54 165 | 53 041 | 52 403 | 52 161 | 51 716 | 51 521 | 50 904 |

| ABIC | 56 115 | 54 146 | 53 013 | 52 365 | 52 113 | 51 659 | 51 521 | 50 857 |

| Entropy | .918 | .844 | .777 | .772 | .743 | .728 | .718 | .781 |

| VLMR LRT p-value | .0000 | .0000 | .0310 | .0009 | .3046 | .2214 | .0620 | .0136 |

| LMR adj LRT p-value | .0000 | .0000 | .0346 | .0011 | .3159 | .2297 | .0662 | .0146 |

Note: N=2.249 unless noted otherwise.

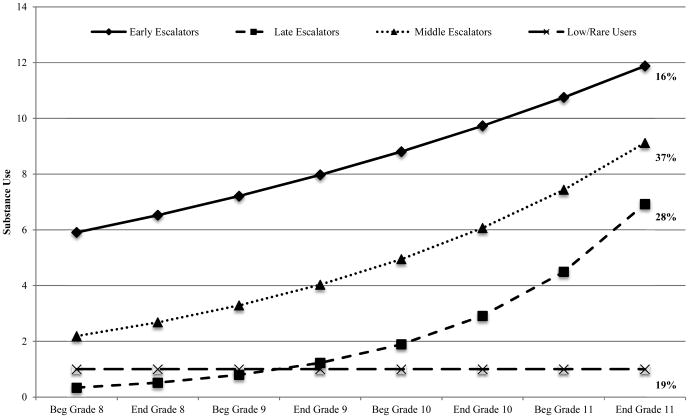

Class-specific parameters (after log transformation back to the raw substance use composite scale) are shown in the upper portion of Table 3 with implied trajectories shown in Figure 2. These three increasing trajectory classes and one stable trajectory class were interpreted as follows (note that due to sample exclusion of lifetime non-users, there is no abstinence class).

Table 3. Class Membership Probability, Latent Variable Means, and Predictors of Class Membership.

| Early Escalators | Middle Escalators | Late Escalators | Low/Rare Users | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implied Class Size | 337 (16%) | 786 (37%) | 607 (28%) | 418 (19%) |

| Average probability of class membership | .930 | .913 | .801 | .824 |

| Latent Variable Means | ||||

| Intercept mean, g0 | 5.90 | 2.19 | 0.33 | 1.00 |

| Slope mean, g1 | 1.65 | 2.77 | 1.25 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||

| Healthy Leisure Predictors of Class Membership | OR | OR | OR | Reference Class |

|

| ||||

| Healthy Leisure | 0.42* | 0.56* | 1.22 | |

| Leisure Planning Efficacy | 1.70* | 1.45* | 0.67 | |

Note: N=2.148. OR = Odds Ratio. Reference category was always Low/Rare Users class (Class 4).

p <.05.

Figure 2.

Substance use trajectory classes. Trajectories are the implied mean values obtained from a 4-class Poisson growth mixture model, after back transformation to the original count metric.

The Early Escalators, comprised 16% (n=337) of the sample and demonstrated the highest initial level of substance use at the beginning of Grade 8 (i.e., indicating early age of initial use) with further increases (i.e., escalation) over time. The Early Escalators represent the highest levels of use across all measurement occasions. The Middle Escalators comprised the largest group with 37% of the sample (n=786). This class had the second highest initial level of substance use and also increased with each additional measurement occasion. The Late Escalators comprised the second largest group with 28% of the sample (n=607). This class demonstrated similar escalation of use to the Early and Middle Escalators, but their initial level was the lowest (almost zero) and they began a sharp acceleration around the end of Grade 10. The final class was the Low/Rare Users, which represented 19% of the sample (n=418) and maintained a low level of use throughout. This class started as the second to lowest users at the first measurement occasion, became the lowest users by the end of Grade 9, and remained there until the final measurement occasion. By the end of Grade 11, the Late Escalators and Low/Rare Users had distinctly different levels of substance use (F (3, 420) = 132.09, p <.0001).

Demographic Sub-Group Characteristics

To better understand characteristics of individuals within trajectory classes, follow-up analyses were conducted using demographic predictors of class membership. Gender, (χ2 (3) = 2.58, n.s.), owning a motor car (χ2 (3) = 5.03, n.s.), and religion (χ2 (9) = 8.01, n.s.) were not significant. The only significant differences were found for age at Wave 1 (F (3, 2125) = 7.00, p <.0001), which identified significant differences between the Early Escalators (13.92 years old) and Late Escalators (13.71 years old) and Late Escalators and the Low/Rare Users (13.83 years old), however the effect size was small (η2 = 0.01).

Influence of Healthy Leisure

Healthy leisure and leisure planning efficacy were included as between-person predictors of substance use trajectory class. Results from a logistic regression, using the Low/Rare Users class as the reference class, are presented in Table 3. Results indicated that individuals with higher levels of healthy leisure were less likely to be in the Early Escalators (OR=0.42) and Middle Escalators (OR=0.56) classes than in the Low/Rare Users class. Results for the leisure planning efficacy factor demonstrated the opposite result where individuals with higher levels of leisure planning efficacy were more likely to be in the Early Escalators (OR=1.70) and Middle Escalators (OR=1.45) than in the Low/Rare Users Class.

Discussion

The current study used a person-centered approach to identify subgroups of substance use development in South African adolescents and the influence of healthy leisure. Results identified four distinct patterns of substance use development with three increasing classes and one stable class. Additionally, the healthy leisure factor served to protect against substance use while individuals high in planning efficacy tended to have higher rates of use. This study is the first of its kind to focus on a sample of South African adolescents and serves to develop a richer understanding of substance use trajectory development and the role of healthy leisure on different developmental trajectories.

Substance Use Development in South African Adolescents

Through the implementation of the nation-wide SAYRBS (Reddy et al., 2010) and a handful of studies obtaining prevalence rates from South African youth (Flisher et al., 2003; Parry et al., 2004), there is a general understanding of how frequently South African adolescents are engaging in substance use and the types and progression of substances being used (Flisher, Parry, Muller, & Lombard, 2002). However, what was lacking was an understanding of how substance use developed across this heterogeneous population. The current study supports findings from previous studies within South Africa that substance use rates generally increase between Grades 8 and 11 (Flisher et al., 2003). As such, we did not find any decreasing trajectory classes despite their presence in other developmental trajectory research. The lack of decreasing trajectory classes may be due to multiple factors. For example, data collection concluded at the end of Grade 11 and therefore may have missed peak use and the subsequent decline in use occurring after high school (see White, Labouvie, & Papadaratsakis, 2005). In addition, the composite measure may have masked any decreases in use if concurrent increases were occurring with other substances.

The Late Escalators represented the second largest trajectory group and were the only group to demonstrate a sharp acceleration around the end of Grade 10. Results of SAYRBS support this acceleration showing the largest increase in the lifetime and past month use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and inhalants to be between Grade 9 and Grade 10 (Reddy et al., 2010). By the end of Grade 10, students are approximately 16 years old on average and this escalation may be the result of multiple factors, both educational and cultural.

The South African educational system is structured such that school is mandatory up through Grade 9 at which point successful students can obtain their General Education and Testing (GET) certificate and leave school to seek employment. Unfortunately, 62% of 15-19 year olds who drop out prior to receiving their GET certificate are unemployed and few ‘second-chance’ resources exist to gain vocational training (Mayer et al., 2011). Students desiring to pursue higher education continue through Grades 10-12 (Education USA, n.d.), also referred to as Further Education and Testing. Due to Grades 10-12 being optional, many adolescents drop out of school sometime after completing their GET Certificate resulting in only 69% of school-aged adolescents enrolled in Grade 11 and 52% in Grade 12 within the 2011 school year (Department of Basic Education, 2013). Not only is this a critical point within the education system, it is also a pivotal point for the adolescents who remain enrolled as being a senior is associated with higher status than underclassmen.

Outside of the educational system, all South Africans are required to possess an identity document, which is obtained after turning 16 years old. This passport-like book is not valid for travel, but rather allows interaction with government services such as voting, getting a driver's license, and applying for social services as well as acquisition of a part-time job (Department of Home Affairs, 2013). For adolescents, possession of their ID book is a symbol of adulthood and although the legal drinking age in South African is 18 years old, it allows adolescents to enter bars or clubs with lax security.

Comparison with other studies

Few studies have compared South African adolescent substance use with US or other developed counterparts, and among those that have (e.g., Reddy, Resnicow, Omardien, & Kambaran, 2007), cross-sectional data are often used. Despite the call for greater monitoring of drug trends over time in South Africa (Acuda, Othieno, Obonda, & Crome, 2011), systematic longitudinal data collection has not occurred. However, keeping similarities (e.g., pattern of substance use initiation; Patrick et al., 2009) and differences (e.g., lower rates of alcohol and marijuana but higher rates of illicit substance use; Reddy et al., 2007) in mind, comparisons with trajectories from other countries provides a starting point for better understanding South African substance use development.

Results from the current study, when compared to adolescent substance use development in other countries, suggests South African adolescents demonstrate similar classifications and patterns. Empirical work identifying substance use trajectories has found approximately three (e.g., early onset use, late onset use, and non-users; Flory et al., 2004), four (e.g., late users, normative users, late-heavy users, early-heavy users; Marti, Stice, & Springer, 2010; Chassin, Presson, Pitts, & Sherman, 2000; Chassin et al., 2002), and six (e.g., never, rare, chronic, decreased, increased, and ‘fling.’; Schulenberg et al., 1996) distinct trajectory classes.

Making direct comparisons between current and previous study results is challenging due to different measures of substance use (e.g., composite, binge drinking), age range of sample, and type/format of questions. However, similar patterns of stable and increasing trajectories were found in both previous studies and the current South African sample. The current study serves to support previous cross-cultural similarities between developed countries and South Africa although contextual factors may vary dramatically (e.g., post-Apartheid transitions, incidence of AIDS).

Influence of Healthy Leisure

The lack of between-person differences in SES was expected due to the sample coming from a homogeneous setting (i.e., Mitchell's Plain; see Weybright et al., 2015 for further information on target data collection area). This homogeneity allowed for between-person differences in healthy leisure to emerge. Based on PBT and its extension to adolescent health behavior (Donovan et al., 1991), adolescents with greater conventionality (e.g., following societal norms) would also engage in health maintaining behaviors (e.g., exercise, healthy leisure activities). Our results support and extend PBT such that individuals who reported experiencing healthy leisure were more likely to be in the Low/Rare Users class than in the highest two substance use classes. There was no difference between the Low/Rare Users class and the Late Escalators class, and by looking at Figure 2, one can see that these trajectory classes both demonstrate low levels of use until Grade 10, when the Late Escalators accelerate.

Results from the healthy leisure factor suggest that adolescents who had high perceptions of positive free time use used fewer substances. PBT would suggest that these adolescents are receiving contextual cues and are observing role models who value engaging in healthy leisure activities. Given the homogeneous characteristics of the sample (i.e., mostly Coloured and similar SES) and that they derived from the same township area, one would expect that access and availability of healthy leisure opportunities and equipment and facilities would be similar. This leaves factors such as perceptions of normative peer leisure engagement and parental leisure engagement, which may be protecting these adolescents against substance use. Unfortunately, data on such factors were not available.

Results for the leisure planning efficacy factor indicated contrasting results when compared to the healthy leisure factor, finding individuals with higher levels of leisure planning efficacy were more likely to be in the Early Escalators and Middle Escalators classes than in the Low/Rare Users class. Both factors were conceptualized as aspects of healthy leisure and consequently were expected to be associated with substance use in the same direction. When looking closer at the leisure planning efficacy factor, none of the specific items include the word ‘healthy.’ Instead, participants may have perceived that they were successful at planning free time activities and construed substance use as a good free time decision. These adolescents may have been confident that they could plan and organize their free time, unfortunately it may have been to engage in substance use behaviors.

These results are counter to the work done related to executive cognitive functioning (ECF), a construct related to planning, initiating, and regulating skills necessary for goal-directed behavior. ECF has been negatively associated with substance use, although the directionality of the relationship is not well understood (Giancola & Tarter, 1999; Pentz & Riggs, 2013). The leisure planning efficacy items from the current study were not intended to target ECF and consequently may be capturing something other than cognitive functioning which is associated with greater substance use.

The current study found a positive association between substance use and leisure planning efficacy, a finding that may apply to other predictors of substance use including sensation seeking and impulsivity. Much research has looked at the relationship between substance use and impulsivity from a social science and a neuropsychological perspective (e.g., Dawe, Gullo, & Loxton, 2004; Spear, 2000). These studies indicate a strong association between impulsivity and substance use finding substance users demonstrated higher levels of sensation seeking and neurologically, maintained greater attention and sensitivity to the reward systems of the brain than light or non-users (Dawe & Loxton, 2004). However, results from the current study suggest individuals with greater ability to plan tend to use more substances, reflecting a more long-term process than explained by impulsivity. While impulsivity may contribute to initial substance use, perhaps the ability to plan (e.g., obtaining alcohol and/or drugs, finding a place to use them, knowing people to use them with) is also important to the maintenance of adolescent substance use. If these maintenance pathways can be better understood, they may become an additional target for reducing substance use.

Prevention Implications

From a prevention perspective, person-centered approaches are extremely important for understanding the individual in context and the multi-faceted influence of risk and protective factors, identifying individuals for targeted interventions, and determining processes that result in intervention effects. The current study takes a first step at understanding how substance use develops in South African adolescents and the influence of leisure on this development. Acknowledging the heterogeneous nature of adolescent substance use development rather than masking it in aggregate techniques allows us to separate low users from heavy and/or escalating users for more targeted intervention. By understanding influences of risk behavior development, we can continue to develop parsimonious intervention strategies to facilitate positive adolescent development.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the current study is a much needed step in understanding South African adolescent substance use, a number of limitations exist. The main limitations include the self-report nature of the data, attrition, composite measurement of substance use, and conceptualization and measurement of the healthy leisure construct.

First, data in the current study were obtained from adolescent self-report and therefore, are vulnerable to self-report bias. During data collection, steps were taken to reduce bias including having individuals answer survey questions on a personal digit assistant, or handheld computer device, to facilitate comfort with providing private information. Attrition is an issue in many longitudinal studies. Although our methodology made use of all available data (i.e., full-information maximum likelihood), our results do not capture those behaviors of dropouts. Prior literature suggests academic disengagement and dropout is associated with risk behavior such as substance use (Townsend et al., 2007) and therefore current results may under-report actual rates of substance use. Previous research has found South African dropouts are 85% more likely to have used tobacco in the past month as compared to non-dropouts (Weybright, Caldwell, Xie, Wegner, Smith, 2016).

One of the challenges in analyzing substance use behavior is how substance use is conceptualized. The current study's composite may mask heavy users of one substance from experimental users of multiple substances. Future analyses should replicate the current methodology looking at each substance separately to provide a better understanding of individual use. Related to healthy leisure, the current study identified two latent constructs which are assumed to represent healthy leisure. To date, there have been no studies that have sought to understand what healthy leisure means to adolescents and consequently, measures within the current study may not represent how South African adolescents conceptualize the construct. To fully understand what healthy leisure means to adolescents, qualitative data are needed. From a methodological perspective, leisure was analyzed as a time-invariant predictor operating at the between-person level. However, the relationship between healthy leisure and substance use may differ at each time point and should be modeled as a time-varying predictor in the future.

Despite these limitations, the current study aids in continuing to understand the relationship between substance use and healthy leisure in South African adolescents and provides a stepping stone for further research to extend current findings as well as address limitations of the study.

Four distinct substance use trajectories included one stable and three increasing

Subjective healthy leisure was associated with low/rare use trajectory

Leisure planning efficacy was associated with extreme use trajectories

Acknowledgments

Portions of this study have been presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, Washington, DC, on May 2013. We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01 DA029084, R01 DA017491, T32 DA0176), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD079994, R24 HD041025), and National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL TR000127).

Footnotes

Although the Population Registration Act of 1950 has since been repealed, the racial categories of White, Black, Coloured, and Indian remain in use. Historically, Black refers indigenous individuals while Coloured refers to someone with mixed race ancestry.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Linda L. Caldwell, Email: lindac@psu.edu.

Nilam Ram, Email: nur5@psu.edu.

Edward A. Smith, Email: eas8@psu.edu.

Lisa Wegner, Email: lwegner@uwc.ac.za.

References

- Acuda W, Othieno CJ, Obondo A, Crome IB. The epidemiology of addiction in Sub-Saharan Africa: A synthesis of reports, reviews, and original articles. The American Journal on Addictions. 2011;20:87–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391-2010.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman A, Phongsavan P. Epidemiology of substance use in adolescence: prevalence, trends and policy implications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;55(3):187–207. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell LL. Leisure. In: Brown BB, Prinstein MJ, editors. Encyclopedia of adolescence. Vol. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell LL, Patrick ME, Smith EA, Palen LA, Wegner L. Influencing adolescent leisure motivation: Intervention effects of HealthWise South Africa. Journal of Leisure Research. 2010;42(2):203–220. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2010.11950202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell L, Smith E, Flisher AJ, Wegner L, Vergnani T, Mathews C, Mpofu E. HealthWise South Africa: Development of a life skills curriculum for young adults. World Leisure. 2004;3:4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(4):483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.14.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2002;70(1):67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychology. 2000;19(3):223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Campbell RT, Ruel E, Richardson JL, Flay BR. A finite mixture model of growth trajectories of adolescent alcohol use: Predictors and consequences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):976–985. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Dishion TJ, Deater-Deckard KD. Variable-and person-centered approaches to the analysis of early adolescent substance use: Linking peer, family, and intervention effects with developmental trajectories. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52(3):421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Gullo MJ, Loxton NJ. Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: Implications for substance misuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(7):1389–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Loxton NJ. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28(3):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Basic Education. Education statistics in South Africa 2011. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=mpjPX4pwF9s%3d&tabid=462&mid=1326.

- Department of Home Affairs. Identity documents. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.home-affairs.gov.za/index.php/identity-documents2.

- Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Adolescent health behavior and conventionality-unconventionality: An extension of problem-behavior theory. Health Psychology. 1991;10(1):52–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Structure of health-enhancing behavior in adolescence: A latent-variable approach. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34(4):346–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Education USA. The educational system of South Africa. n.d. Retrieved from U.S. Embassy website: http://southafrica.usembassy.gov/root/pdfs/study_sa_profile_rev100630.pdf.

- Flisher AJ, Parry CD, Evans J, Muller M, Lombard C. Substance use by adolescents in Cape Town: prevalence and correlates. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisher AJ, Parry CD, Muller M, Lombard C. Stages of substance use among adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Substance Use. 2002;7(3):162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16(1):193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Tarter RE. Executive cognitive functioning and risk for substance abuse. Psychological Science. 1999;10(3):203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT, et al. Bucholz KK. Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for adult alcohol and drug dependence: Evidence from a twin design. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:109–118. doi: 10.10.17/S0033291705006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Problem behavior theory - A brief overview. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.colorado.edu/ibs/jessor/pb_theory.html.

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychological development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynski AT, Mannell RC, Manske SR. Leisure and risky health behaviors: A review of evidence about smoking. Journal of Leisure Research. 2008;40(3):404–441. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KTH, Vandell DL. Out-of-school time and adolescent substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.003. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti CN, Stice E, Springer DW. Substance use and abuse trajectories across adolescence: A latent trajectory analysis of a community-recruited sample of girls. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33(3):449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MJ, Gordhan S, Manxeba R, Hughes C, Foley P, Maroc C, et al. Nell M. Johannesburg, South Africa: Development Bank of Southern Africa; 2011. Towards a youth employment strategy for South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/fileadmin/uploads/aeo/PDF/DPD%20No28.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, Brook JS, Kachieng'a MA. Perceptions of sexual risk behaviours and substance use among adolescents in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. AIDS Care. 2006;18(3):215–219. doi: 10.1080/09540120500456243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User's guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Anderson AL. Unstructured socializing and rates of delinquency. Criminology. 2006;42(3):519–549. [Google Scholar]

- Palen LA, Caldwell LL, Smith EA, Gleeson SA, Patrick ME. A mixed-method analysis of free-time involvement and motivation among adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa. Leisure/Loisir. 2011;35(3):227–252. doi: 10.1080/14927713.2011.615641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palen LA, Patrick ME, Gleeson SL, Caldwell LL, Smith EA, Wegner L. Leisure constraints for adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa: A qualitative study. Leisure Sciences. 2010;32:434–452. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2010.510975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palen LA, Smith EA, Caldwell LL, Flisher AJ. Longitudinal patterns of cigarette use among girls in Cape Town, South Africa. In: Wesley MK, Sternbach IA, editors. Smoking and women's health. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2008. pp. 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Palen LA, Smith EA, Flisher AJ, Caldwell LL, Mpofu E. Substance use and sexual risk behavior among South Africa eight grade students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:761–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CDH, Myers B, Morojele NK, Flisher AJ, Bhana A, Donson H, Plüddemann A. Trends in adolescent alcohol and other drug use: findings from three sentinel sites in South Africa (1997-2001) Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasche S, Myers B. Substance misuse trends in South Africa. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 2012;27(3):338–341. doi: 10.1002/hup.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Collins LM, Smith E, Caldwell L, Flisher A, Wegner L. A prospective longitudinal model of substance use onset among South African adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:647–662. doi: 10.1080/10826080902810244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentz MA, Riggs NR. Longitudinal relationships of executive cognitive function and parent influence to child substance use and physical activity. Prevention Science. 2013;14(2):229–237. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Grimm KJ. Methods and measures: growth mixture modeling: a method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33(6):565–576. doi: 10.1177/0165025409343765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SP, James S, Sewpaul R, Koopman F, Funani NI, Sifunda S, et al. Omardien RG. Umthente uhlaba usamila – The South African youth risk behavior survey 2008. 2010 Retrieved from South African Medical Research Council website: http://www.mrc.ac.za/healthpromotion/healthpromotion.htm.

- Reddy P, Resnicow K, Imardien R, Kambaran N. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among high school students in South Africa and the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(10):1859–1864. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O'Malley P, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57(3):289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp EH, Coffman DL, Caldwell LL, Smith EA, Wegner L, Vergnani T, Mathews C. Predicting substance use behavior among South African adolescents: The role of leisure experiences across time. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2011;35(4):343–351. doi: 10.1177/0165025411404494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Palen LA, Caldwell LL, Flisher AJ, Graham JW, Mathews C, et al. Vergnani T. Substance use and sexual risk prevention in Cape Town, South Africa: An evaluation of the HealthWise program. Prevention Science. 2008;9:311–321. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Neurobehavioral changes in adolescence. Current Directions in Psychological Sciences. 2000;9(4):111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tibbits MK, Caldwell LL, Smith EA, Wegner L. The relation between profiles of leisure-activity participation and substance use among South African youth. World Leisure. 2009;3:150–159. doi: 10.1080/04419057.2009.9728267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbits MK, Smith EA, Caldwell LL, Flisher AJ. Impact of HealthWise South Africa on polydrug use and high-risk sexual behavior. Health Education Research. 2011;26(4):653–663. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend L, Flisher AJ, King G. A systematic review of the relationship between high school dropout and substance use. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10(4):295–317. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Martino SC, Klein DJ. Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: A comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner L. Through the lens of a peer: Understanding leisure boredom and risk behaviour in adolescence. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011;41(1):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner L, Flisher A, Muller M, Lombard C. Leisure boredom and substance use among high school students in South Africa. Journal of Leisure Research. 2006;38(2):249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Weybright EH, Caldwell LL, Ram N, Smith EA, Jacobs J. The dynamic association between healthy leisure and substance use in South African adolescents: A state and trait perspective [Special issue] World Leisure Journal. 2014;56(2):99–109. doi: 10.1080/16078055.2014.903726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weybright EH, Caldwell LL, Ram N, Smith EA, Wegner L. Boredom prone or nothing to do? Distinguishing between trait and state leisure boredom and its association with substance use in South African adolescents. Leisure Sciences. 2015;37(4):311–331. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2015.1014530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weybright EH, Caldwell LL, Xie H, Wegner L, Smith EA. Predicting secondary school dropout among South African adolescents: A survival analysis approach. 2016 doi: 10.15700/saje.v37n2a1353. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW, Papadaratsakis V. Changes in substance use during the transition to adulthood: A comparison of college students and their noncollege age peers. The Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Witt PA, Caldwell LL. The rationale for recreation services for youth: An evidenced based approach. Ashburn, VA: National Recreation and Park Association; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.nrpa.org/uploadedFiles/nrpa.org/Publications_and_Research/Research/Papers/Witt-Caldwell-Full-Research-Paper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zaslow MJ, Takanishi R. Priorities for research on adolescent development. American Psychologist. 1993;48(2):185–192. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]