Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the knowledge, beliefs, and practices of nursing assistants (NAs) providing oral hygiene care to frail elders in nursing homes, with the intent of developing an educational program for NAs.

Methods

The study occurred in two economically and geographically diverse nursing homes. From a sample size of 202 NAs, 106 returned the 19-item Oral Care Survey.

Results

The NAs reported satisfactory knowledge regarding the tasks associated with providing mouth care. The NAs believed that tooth loss was a natural consequence of aging. They reported that they provided mouth care less frequently than is optimal but cited challenges such as caring for persons exhibiting care-resistive behaviors, fear of causing pain, and lack of supplies.

Conclusion

Nurses are in a powerful position to support NAs in providing mouth care by ensuring that they have adequate supplies and knowledge to respond to resistive behaviors.

Nursing assistants (NAs) account for 65% of the nursing staff in nursing homes (NHs)1,2 and provide most of the physical care for frail, functionally dependent, and cognitively impaired elders. Older adults are at risk for oral health problems, and these problems can affect systemic health. The purpose of the study reported here was to collect and analyze data surrounding the knowledge, beliefs, and self-reported practices of NAs providing oral hygiene care to frail, functionally dependent, and cognitively impaired elders.

Background

Ninety-one percent of NH residents are aged 65 years or older; 46% are aged 85 years or older. Seventy-five percent require assistance with 3 or more activities of daily living (ADLs)1,2 showering/bathing (including oral care), dressing, and eating are the most common ADLs with which residents require assistance.1,2 Self-care is further compromised by cognitive impairment; 70% of NH residents exhibit some form of cognitive impairment regardless of diagnoses.

Older adults, especially the frail, functionally dependent, and cognitively impaired residents in NHs, are at risk for tooth loss from dental caries and periodontal disease. The average NH elder takes 8 medications daily.2 Many medications commonly prescribed for elderly patients, especially calcium channel blockers and antiseizure medications, result in gingival overgrowth, which further predisposes the NH resident to caries and periodontal disease.3,4 Other medications, including anticholinergics, antihypertensives, antidepressants, diuretics, anxiolytics, and antihistamines, diminish salivary production and alter the ability of the oral environment to fight the effects of pathogens.3,4 Older adults may form plaque more quickly than their younger counterparts when oral care is not routinely performed; this may be due to gingival recession, which exposes more tooth to the oral environment and also to reduced salivary flow.3 Tooth loss may cause shifting of remaining teeth to the point where occlusal surfaces no longer articulate, interfering with chewing and swallowing functions and potentially resulting in malnutrition and weight loss.

There is emerging evidence that oral health affects systemic health.5 Poor oral health appears to increase the risk of poor nutrition,6 ischemic stroke,7 carotid atherosclerosis,8–10 poor glycemic control in diabetes,11,12 and NH-acquired pneumonia.13–20 However, despite the tremendous importance of oral health in frail, functionally dependent, and cognitively impaired NH elders, there is evidence that oral care is suboptimal. Many studies have documented the overall poor oral health of NH elders,13,21–25 especially those with dementia.26 Inadequate daily oral care provided by caregivers was a significant factor for poor oral health.27–29 We embarked on this study to collect and analyze data surrounding the knowledge, beliefs, and self-reported practices of NAs who provide oral care to NH residents. Other oral health educational interventions designed for NAs did not assess their learning needs; consequently, those educational interventions showed no change in oral health outcomes.30 We used the data collected in the survey to develop an educational oral care intervention designed to address the specific challenges faced by the NAs in this sample. The results of the survey are reported in this article.

Setting and Sample

After approval from the institutional review board, NAs were recruited from 2 NHs. NH1 was a 200-bed urban for-profit facility that received the majority of its reimbursement from Medicaid. NH2 was a 250-bed suburban not-for-profit facility that received the majority of its reimbursement from private-paying residents. NAs were approached during existing in-services during all shifts and weekends during a 30-day period. They were asked to complete the survey. Of a total combined population of 202 NAs, 106 returned the surveys for a response rate of 52.5%. Characteristics of the NAs are reported in Table 1. The majority were female. The average time as an NA was 11 years (range: 2 months–30 years), and the average length of time working at the current NH was 5.5 years (range: 1 month–30 years). The NAs worked all shifts, but a majority worked either day shift (n = 39, 36.8%) or evening shift (n = 38, 35.8%). There were no statistical differences between sites for sex, length of time working as an NA, or duration of employment at the NH. The NAs who were employed at NH2 appeared to be better educated than their counterparts at NH1 because more NAs at NH2 had completed high school and had some type of college education. The difference between the 2 groups, although not statistically significant, did approach statistical significance (Pearson = .07).

Table 1.

Comparison of Nursing Assistant (NA) Demographic Information by Nursing Home

| Demographic Information | NH1 N = 30, % (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | NH2 N = 76, % (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3.3% | 7.0% | Pearson = .48 |

| Female | 96.7% | 93.0% | |

| Years Experience as an NA | (9.4 ± 4.9) | (11.6 ± 9.3) | P = .13 |

| Years Experience in current NH | (4.1 ± 4.2) | (6.0 ± 8.2) | P = .15 |

| Education* | |||

| Started high school | 10.4% | 9.2% | Pearson = .07 |

| Completed high school | 31.0% | 40.8% | |

| Started technical training | 6.9% | 0 | |

| Completed technical training | 27.6% | 12.7% | |

| Started college | 17.2% | 22.5% | |

| Completed college | 3.4% | 11.3% | |

| Started post-college | 3.4% | 0 | |

| Completed post-college | 0 | 2.8% | |

Totals do not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Measurement and Methods

The Oral Care Survey measured the knowledge, beliefs, and self-reported practices of NAs who provided mouth care to frail and functionally dependent NH elders. The survey was a modification of one used by Grap et al.31 in their study of the oral care practices by nurses in intensive care units. Additional questions were added on the basis of findings in the literature. The final version of the survey contained 2 questions about oral care knowledge, 5 questions about oral care practices, 4 questions about oral care beliefs, 6 demographic questions, and 2 open-ended questions regarding challenges and topics for future oral care training programs (available by request from Jablonski). A 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) was used for 8 of the questions about oral care practices and beliefs. VASs have been successfully used in many clinical and research endeavors, and their validity and reliability have been extensively tested.32–34 These scales provide a reliable and valid method to quantify subjective experiences.

Knowledge was measured by 2 questions. The first question was open-ended, “At this nursing home, what is the routine for oral care?” The second question asked if the NAs knew whether their NH had a written policy for oral care.

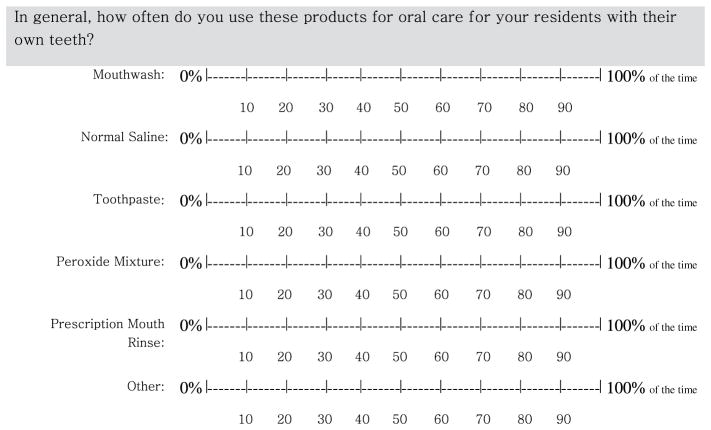

Beliefs were measured by the following four questions: “Brushing and flossing daily prevent gum disease,” “Health of the mouth is related to health of the body,” “As people age, they naturally lose their teeth,” and “Dentures should be removed at night.” The first 3 questions had previously been developed and tested by Pyle and colleagues35: 2 supported the construct of value of oral health and 1 reflected a common myth about aging and dentition.35 The fourth question was added about denture removal at night because previous researchers had noted a knowledge deficiency in this area.36 The anchors used for these 4 questions were “Disagree” and “Agree.” A sample VAS is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Questions measuring beliefs using VAS from the Oral Health Survey.

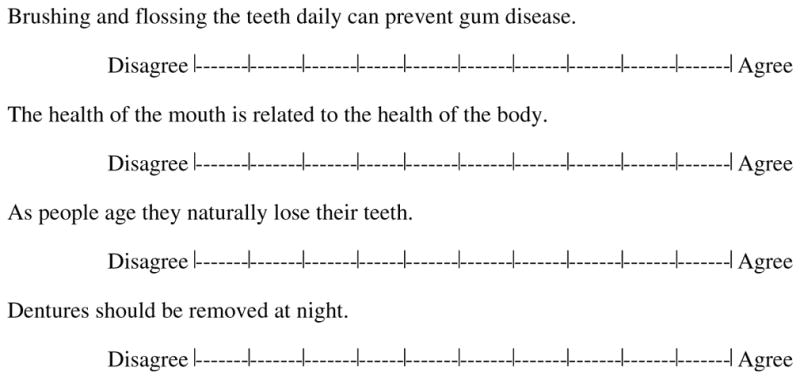

Practices were measured by 5 questions. The first of the 5 questions required respondents to select, from a list, how many times a day they provided mouth care. The remaining 4 questions required respondents to rate on a VAS the frequency they used specific mouth care products (mouthwash, normal saline, toothpaste, peroxide mixture, prescription mouth wash, or other) for NH residents with varying types of dentition (“own teeth,” “own teeth and dentures,” “dentures with no natural teeth,” “no natural teeth and no dentures”). The anchors for these VASs were “0” and “100% of the time.” An example of one of the questions with the VAS is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example of a reported practice question visual analogue scale from the Oral Care Survey.

The last 2 questions, “What are the challenges you face when you give oral care” and “What topics would you want to hear about if you were able to attend a training program about oral care” were included in order to help us develop an appropriate oral care educational intervention for the NAs who completed the surveys.

We tested the Oral Health Survey for readability and ease of administration on a sample of 15 NAs from northern Virginia. Based on their feedback, the survey was modified as follows: the VASs were divided into 10-mm increments, and some of the questions were reworded for readability. The second version of the Oral Health Survey was tested again with a different group of 15 NAs, who offered no additional suggestions for improvement.

Surveys were distributed to all NAs attending scheduled in-services provided by the facility. The research team was granted access to the NAs during these times; we explained the purpose of the study and requested that the NAs complete the survey. We did not conduct any oral care educational programs during these scheduled times. Quantitative data from the returned surveys were analyzed using descriptive statistics and t tests run by the statistical software JMP 7.0 (SAS; Cary, NC; 2007). Data from open-ended questions were organized into themes.

Results

The questions on the Oral Care Survey for NAs comprised 3 areas: knowledge, beliefs, and self-reported practices. Knowledge was measured using 2 questions, 1 about the routine for oral care and 1 about the presence or absence of a written mouth care policy. When asked to describe the routine for oral care in their facility, 79 provided responses that fell predominantly into 1 of 2 categories: timing (e.g., “upon awakening,” “before bedtime”) and task (e.g., “use a toothbrush”). Only one respondent wrote about the use of warm water for rinsing, and only 1 mentioned flossing. In response to the second knowledge question, “The nursing home has a written policy for oral care,” 79 of the NAs completing the survey believed their NH had a written policy for oral care. Ten did not believe their NH had such a policy, and 17 left the question blank.

Beliefs were measured by 4 questions listed in Table 2. Respondents were asked, using the VAS, how much they agreed or disagreed with each statement. Higher numbers were associated with agreement, lower numbers with disagreement. Generally, NAs believed that brushing and flossing prevented gum disease, that oral health was linked to systemic health, and that dentures should be removed at night. Their views regarding tooth loss and aging were more polarized. When we examined the distribution of scores for this statement, we noted that 51 of the 101 respondents who answered this question provided a score of 90 or higher on the VAS. There was no correlation between education level and VAS score and no difference between NAs at either NH. In other words, nearly half of the NAs regardless of educational level or NH site were inclined to agree with the statement, “As people age, they naturally lose their teeth.”

Table 2.

Beliefs of NAs Regarding Oral Health

| Statement | N | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Brushing and flossing daily prevent gum disease”* | 97 | 93.3 | 17.2 |

| “Health of mouth is related to health of body”* | 95 | 87.9 | 24.9 |

| “As people age they naturally lose their teeth”* | 101 | 60.6 | 38.1 |

| “Dentures should be removed at night” | 101 | 93 | 21.4 |

Reproduced from Pyle MA, Nelson S, Sawyer DR. Nursing assistants’ opinions of oral health care provision. Special Care in Dentistry. 1999;19(3):112–7. Written permission received from MA Pyle and Special Care in Dentistry to reproduce questions.

Table 3 lists the responses that NAs provided to the questions designed to elicit information regarding their self-reported practices. Forty-four reported that they performed mouth care daily, 28 reported that they performed mouth care twice daily, and 21 reported that they performed mouth care 3 times a day. Toothpaste, mouthwash, and commercial denture cleaners were the most frequently used items regardless of dentition. For dentate NH residents, toothpaste was the most popular item used for oral care (68.4%), followed by mouthwash (60.1%). When caring for NH residents who had both natural dentition and dentures, NAs reported that they used toothpaste and mouthwash most often as well as commercial denture cleaner. NH residents who wore only dentures received mouthwash 65.3% of the time, toothpaste 47.7% of the time, and commercial denture cleansers 63.0% of the time. NAs reported that they used mouthwash 70.2% of the time and toothpaste 30.1% of the time when providing oral care for NH residents with neither dentition nor dentures. NAs also reported that they used “other” products nearly a quarter of the time regardless of the type of dentition. NAs also indicated that they used commercial denture cleaner 13.5% of the time for persons who did not wear dentures.

Table 3.

Self-reported Practices of NAs Regarding Oral Care

| Question | Responses (Percentages) |

|---|---|

| In general, how often do you perform oral care for your residents? | Daily: 44 (41.5%) Twice daily: 28 (26.4%) Three times daily: 21 (19.8%) Four or more times daily: 5 (4.7%) Missing responses: 8 (7.5%) |

| Questions (Using Visual Analogue Scales for Frequency) | Mean (SD) |

| In general, how often do you use these products for oral care for your residents with their own teeth? | Mouthwash: 60.1% (27.1%) Normal Saline: 14.0% (23.3%) Toothpaste: 68.4% (29.8%) Peroxide Mixture: 15.0% (27.4%) Prescription Mouthwash: 18.8% (30.4%) Other: 18.8% (30.4%) |

| In general, how often do you use these products for oral care for your residents with their own teeth and dentures (full or partial plate)? | Mouthwash: 65.4% (28.6%) Normal Saline: 15.7% (26.3%) Toothpaste: 67.8% (32.3%) Peroxide Mixture: 17.1% (28.1%) Prescription Mouthwash: 25.3% (32.8%) Commercial Denture Cleaner: 57.2% (37.5%) Other: 22.3% (33.0%) |

| In general, how often do you use these products for oral care for your residents with dentures but with no natural teeth? | Mouthwash: 65.3% (32.0%) Normal Saline: 13.8% (24.2%) Toothpaste: 47.7% (37.9%) Peroxide Mixture: 13.4% (25.6 %) Prescription Mouthwash: 24.4% (33.3%) Commercial Denture Cleaner: 63.0% (38.9%) Other: 25.5% (32.5%) |

| In general, how often do you use these products for oral care for your residents with no natural teeth and no dentures? | Mouthwash: 70.2% (31.3%) Normal Saline: 17.1% (29.4%) Toothpaste: 30.1% (36.6%) Peroxide Mixture: 13.2% (26.3%) Prescription Mouthwash: 23.1% (33.1%) Commercial Denture Cleaner: 13.5% (28.9%) Other: 27.0% (35.8%) |

The last 2 questions were designed to help us develop an appropriate oral care educational intervention for the NAs. When asked about challenges associated with providing mouth care, 3 major themes emerged: care-resistive behaviors, fear of causing pain or injury, and lack of supplies. When discussing care-resistive behavior, 1 respondent noted, “Most residents refuse mouth care. It’s hard to clean their mouth when they will not open their mouth or when they bite you.” Another responded that resistive behavior included “having patients spit and even vomit on you.” NAs were fearful of inadvertently causing pain when providing oral care because “sometimes residents feel pain on their gums and that makes them not willing to have them cleaned. But, with regular cleaning, the pain goes [away].” Many were concerned about causing gums to bleed or residents swallowing mouthwash. NAs wrote about the shortage of supplies such as denture tablets. When questioned about potential topics for future educational programs, the major theme “best mouth care under difficult circumstances” emerged: “What can we do for residents who refuse oral care?” “I would like to hear about how to give proper care when patients close their mouths and resist.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the knowledge, beliefs, and practices of NAs providing oral hygiene to frail elders to design an educational intervention on the basis of their responses. According to their responses, the NAs possessed adequate knowledge regarding the minimum amount of oral hygiene necessary for frail and functionally dependent elders. They knew that mouth care should be provided, at a minimum, twice daily.

The NAs believed that brushing and flossing prevented gum disease, that oral and systemic health were related, and that dentures should be removed every night. These results were similar to the ones reported by Pyle et al.,35 although those researchers used a 4-point Likert-type scale, and we measured agreement using VASs. Pyle et al. noted that 36% of their respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the myth that tooth loss is a natural consequence of aging. Nearly half of our respondents, however, had VAS scores of 90 or higher, indicating a propensity to agree with the myth. Additional research is required to determine the reason for this difference.

In regard to practices, the NAs reported that toothpaste, mouthwash, and denture cleaner were most often used for oral care regardless of dentition. One disconcerting finding was the report that NAs used toothpaste 68.4% of the time for residents with teeth. NAs also reported only using toothpaste 47.7% of the time for residents with dentures only. Toothpaste can abrade denture surfaces. This finding is also problematic, given that plaque can readily collect on dentures and harbor harmful pathogens.18,19 The answers that the NAs provided to the question regarding the challenges of providing mouth care may offer insight into these results: lack of supplies. NAs may only be using toothpaste 68.4% of the time because it is only available two thirds of the time. The final finding that we question is the use of denture cleansers for persons without dentures. This may be the result of the way the VAS was organized, which may have increased the probability of NAs inadvertently misreading or misinterpreting the question.

NAs’ reported practices did not correspond to their knowledge. Despite their knowledge that mouth care should be provided at least twice daily, 44% reported that they performed mouth care only once a day. Hardy and colleagues reported in 1995 that 26% of the surveyed NAs reported brushing teeth for NH residents once daily, and 21% reported brushing teeth twice daily.37 Our numbers may be higher because we included all mouth care, not just tooth brushing. We believe that the reasons for differences between knowledge and practice were elucidated in the themes identified from the last 2 questions of the survey. When faced with care-resistive behaviors, lack of supplies, and the possibility of inadvertently causing pain or injury, NAs may perform mouth care less frequently than they wish. Other researchers have found that uncooperative NH residents, staffing, and lack of time contributed to the lack of mouth care provided by NAs.38,39 Interestingly, our sample did not identify lack of staffing or lack of time as challenges they encountered when providing mouth care.

One limitation of the survey was the use of the VASs. We were unable to locate studies in which NAs were asked to complete VASs. We employed this method to provide a reliable and valid method to quantify subjective experiences. The use of VASs to measure the frequency of use for mouth care products may be inappropriate in an environment where the products may be in short supply, thus skewing the results. The use of VASs to measure the degree of one’s agreement or disagreement with a statement may be more appropriate. Thus some of the NAs may have had difficulty responding to specific VAS questions despite verbal explanations before the completion of the survey. Their difficulty with the VASs may ironically have contributed to more categorical or dichotomous responses instead of continuous responses. The use of the VAS also made comparisons with other reported findings challenging. Another limitation of the survey was the lack of distinction between mouthwash with fluoride and mouthwash without fluoride. Other researchers have reported the use of both by NAs.37,38 NAs may also have had problems distinguishing between the categories of products listed in the survey. Finally, this survey relied on the self-report of NAs. One recent study found discrepancies between the actual and reported mouth care provided by NAs.40 More research is needed in this area.

When examining the findings of the survey as a whole, we noted that an educational intervention based on specific methods to help NAs provide mouth care to persons exhibiting care-resistive behaviors would be beneficial. We developed an educational program that used interventions rooted in the Need-Driven Dementia-Compromised Behavior Model41 and implicit memory theory.42 The basis of the program is that care-resistive behavior is often the resident’s way of communicating fear, discomfort, or misinterpretation of the NAs intent. By changing how the NA approaches the resident, the NA may find less care-resistive behaviors when providing mouth care—or any other care activity. The educational program summarized best oral care practices, addressed common myths associated with aging and oral health, and provided concrete person-specific strategies both to help NAs prevent care-resistive behaviors and to deescalate care-resistive behaviors while providing mouth care. We are currently re-fining the educational program and plan to test the program on larger samples of NAs in geographically diverse areas.

Conclusion

Mouth care is an important part of the self-care needs of institutionalized older adults. Nurses are in a powerful position to guide NAs and help them by modeling behavior—that is, by demonstrating techniques that minimize both care-resistive behaviors and functional dependency. For example, implicit memory is the ability to automatically complete a task learned in childhood if appropriately cued, and it remains intact even in very late stages of dementia.42 An NA who tries to brush an elder’s teeth may encounter care-resistive behaviors and may be unwittingly increasing dependency, creating a negative spiral of continued care resistiveness and dependency. However, an NA who is shown how to cue the elder by putting the toothbrush in his or her hand and pantomiming the act of brushing may be more successful in promoting good mouth care while preserving the elder’s functional abilities. Nurses can also improve the environment of mouth care by ensuring that NAs have sufficient quantity and quality of supplies to administer care. This study represents one step toward addressing some of the problems faced by NAs who wish to provide excellent mouth care to their NH residents.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, grant no. R21DE16464-02 (principal investigator: Jablonski). The authors wish to thank Ann Kolanowski and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback.

Contributor Information

Rita A. Jablonski, School of Nursing, College of Health and Human Development, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Cindy L. Munro, School of Nursing, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.

Mary Jo Grap, School of Nursing, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.

Christine M. Schubert, School of Medicine, Department of Biostatistics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.

Mary Ligon, Behavioral Sciences Department, York College of Pennsylvania, York, PA.

Pamela Spigelmyer, School of Nursing, College of Health and Human Development, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

References

- 1.Gabrel CS. An overview of nursing home facilities: data from the 1997 National Nursing Home Survey. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2000. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, No. 280; report no. 311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabrel CS. Characteristics of elderly nursing home current residents and discharges: data from the 1997 National Nursing Home Survey. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2000. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, No. 312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shay K, Ship JA. The importance of oral health in the older patient. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:16. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ettinger RL. Review: xerostomia: a symptom which acts like a disease. Age Ageing. 1996;25:409–12. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto M, Yamanaka K, Shimosato T, et al. Oral condition and health status of people aged 80–85 years. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2006;6:60–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rauen MS, Moreira AMM, Marino MCM, et al. Oral condition and its relationship to nutritional status in the institutionalized elderly population. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 2006;106:1112–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshipura KJ, Hung HC, Rimm EB, et al. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and incidence of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:47–52. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000052974.79428.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Rundek T, et al. Periodontal microbiota and carotid intima-media thickness: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST) Circulation. 2005;111:576–82. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154582.37101.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desvarieux M, Schwahn C, Volzke H, et al. Gender differences in the relationship between periodontal disease, tooth loss, and atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2004;35:2029–35. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000136767.71518.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engebretson SP, Lamster IB, Elkind MS, et al. Radiographic measures of chronic periodontitis and carotid artery plaque. Stroke. 2005;36:561–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155734.34652.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai C, Hayes C, Taylor GW. Glycemic control of type 2 diabetes and severe periodontal disease in the US adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:182–92. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart JE, Wager KA, Friedlander AH, et al. The effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:306–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028004306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adachi M, Ishihara K, Abe S, et al. Effect of professional oral health care on the elderly living in nursing homes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:191–5. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.123493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mojon P. Oral health and respiratory infection. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:340–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mojon P, Bourbeau J. Respiratory infection: how important is oral health? Curr Opin Pulmon Med. 2003;9:166–70. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mylotte JM. Nursing home-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1205–11. doi: 10.1086/344281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shay K. Infectious complications of dental and periodontal diseases in the elderly population. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1215–23. doi: 10.1086/339865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terpenning M. Geriatric oral health and pneumonia risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1807–10. doi: 10.1086/430603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terpenning MS, Taylor GW, Lopatin DE, et al. Aspiration pneumonia: dental and oral risk factors in an older veteran population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:557–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langmore SE, Terpenning MS, Schork A, et al. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia: how important is dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1998;13:69–81. doi: 10.1007/PL00009559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frenkel H, Harvey I, Newcombe RG. Improving oral health in institutionalised elderly people by educating caregivers: a randomised controlled trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:289–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagramian RA, Heller RP. Dental health assessment of a population of nursing home residents. J Gerontol. 1977;32:168–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shareff HL, Strauss RP. Behavioral influences on the feasibility of outpatient dental care for nursing home residents. Special Care Dent. 1985;5:270–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1985.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiyak HA, Grayston MN, Crinean CL. Oral health problems and needs of nursing home residents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:49–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray PE, Ede-Nichols D, Garcia-Godoy F. Oral health in Florida nursing homes. Int J Dent Hyg. 2006;4:198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2006.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rejnefelt I, Andersson P, Renvert S. Oral health status in individuals with dementia living in special facilities. Int J Dent Hyg. 2006;4:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2006.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shay K. Dental management considerations for institutionalized geriatric patients. J Prosthet Dent. 1994;72:510–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacEntee M, Weiss R, Waxler-Morrison NE, et al. Factors influencing oral health in long term care facilities. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:314–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolan TA. Implications of access, utilization and need for oral health care by the non-institutionalized and institutionalized elderly on the dental delivery system. J Dent Educ. 1993;57:876–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacEntee MI, Wyatt CCL, Beattie BL, et al. Provision of mouth-care in long-term care facilities: an educational trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grap MJ, Munro CL, Ashtiani B, et al. Oral care interventions in critical care: frequency and documentation. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12:113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCormack HM, Horne DJ, Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: a critical review. Psychol Med. 1988;18:1007–19. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700009934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crouch R, Dale J. Identifying feelings engendered during triage assessment in the accident and emergency department: the use of visual analogue scales. J Clin Nurs. 1994;3:289–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.1994.tb00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanco VL, Levy SM, Ettinger RL, et al. Challenges in geriatric oral health research methodology concerning caregivers of cognitively impaired elderly adults. Special Care Dent. 1997;17:129–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1997.tb00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pyle MA, Nelson S, Sawyer DR. Nursing assistants’ opinions of oral health care provision. Special Care Dent. 1999;19:112–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1999.tb01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Preston AJ, Punekar S, Gosney MA. Oral care of elderly patients: nurses’ knowledge and views. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:89–91. doi: 10.1136/pmj.76.892.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy DL, Brangan PP, Darby ML, et al. Self-report of oral health services provided by nurses’ aides in nursing homes. J Dent Hyg. 1995;69:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chalmers JM, Levy SM, Buckwalter KC, Ettinger RL, Kambhu PP. Factors influencing nurses’ aides provision of oral care for nursing facility residents. Special Care Dent. 1996;16:71–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1996.tb00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kambhu PP, Levy SM. Oral hygiene care levels in Iowa intermediate care facilities. Special Care Dent. 1993;13:209–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1993.tb01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coleman P, Watson NM. Oral care provided by certified nursing assistants in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:138–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Algase DL, Beck C, Kolanowski A, et al. Need-driven dementia-compromised behavior: An alternative view of disruptive behavior. Am J Alz Dis. 1996;11(10):12–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harrison BE, Son GR, Kim J, Whall AL. Preserved implicit memory in dementia: a potential model for care. Am J Alz Dis Other Dement. 2007;22:286–93. doi: 10.1177/1533317507303761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]