Abstract

Botrytis species are generally considered to be aggressive, necrotrophic plant pathogens. By contrast to this general perception, however, Botrytis species could frequently be isolated from the interior of multiple tissues in apparently healthy hosts of many species. Infection frequencies reached 50% of samples or more, but were commonly less, and cryptic infections were rare or absent in some plant species. Prevalence varied substantially from year to year and from tissue to tissue, but some host species routinely had high prevalence. The same genotype was found to occur throughout a host, representing mycelial spread. Botrytis cinerea and Botrytis pseudocinerea are the species that most commonly occur as cryptic infections, but phylogenetically distant isolates of Botrytis were also detected, one of which does not correspond to previously described species. Sporulation and visible damage occurred only when infected tissues were stressed, or became mature or senescent. There was no evidence of cryptic infection having a deleterious effect on growth of the host, and prevalence was probably greater in plants grown in high light conditions. Isolates from cryptic infections were often capable of causing disease (to varying extents) when spore suspensions were inoculated onto their own host as well as on distinct host species, arguing against co-adaptation between cryptic isolates and their hosts. These data collectively suggest that several Botrytis species, including the most notorious pathogenic species, exist frequently in cryptic form to an extent that has thus far largely been neglected, and do not need to cause disease on healthy hosts in order to complete their life-cycles.

Keywords: gray mold, systemic infection, wild vegetation, Botrytis

Introduction

Botrytis is an ascomycete fungal genus of plant pathogens. Most members of the genus are specialized species infecting a narrow range of monocotyledonous host plants. Typically, they are aggressive, necrotrophic pathogens (Staats et al., 2005). Some have an extended quiescent phase following infection (Botrytis allii). An exception to the rule of narrow host range is the clade including the species Botrytis cinerea sensu lato. This clade is by far the most economically damaging group within the genus; B. cinerea s.l. has a recorded host range including over 1400 (mostly dicotyledonous) hosts (Elad et al., 2015). The typical symptoms leading to economic loss are the occurrence of spreading, fast-growing necrotic lesions bearing abundant pigmented, hydrophobic, conidia.

Botrytis conidia are dispersed in windy conditions. Rainfall aids dispersal through the sharp motions of infected tissues resulting from raindrop impact. Conidia require high humidity to infect; infection tests in laboratory are typically performed with high concentrations of spore suspensions (106/ml). The likelihood that conidia will produce a lesion is greatly increased if a nutrient source is available due to host cell damage, insect honeydew or exogenously supplied sugars (van den Heuvel, 1981; Dik, 1992).

Typically B. cinerea causes loss in crops by damage to the harvestable part of the crop, flowers, fruits, or leaves, or by girdling stems. The tools to manage B. cinerea in crops include (partial) host resistance, avoidance of damage allowing saprophytic infections to occur and then spread, environmental modification to reduce the probability of conditions suitable for spore germination and dispersal, and the use of fungicide. The latter can be effective, but typically there are no consistent critical periods. Although in a single experiment, one or a few fungicide application times may stand out as effective, these application times may not be reproducible in repeat experiments or easy to relate to environmental conditions (e.g., McQuilken and Thomson, 2008). Spores are present in low concentrations in the air over most of the year (Hausbeck and Moorman, 1996; Kerssies et al., 1997; Boff et al., 2001; Boulard et al., 2008). A common strategy for application of fungicides is to maintain continuous cover. This is undesirable on environmental and economic grounds and leads to rapid development of resistance to new fungicides.

A number of publications have suggested that a range of plant species may harbor infections by B. cinerea s.l. and other species, including Botrytis deweyae, which cause no visible symptoms on the plant at the initial time of infection, are long-lived, can be isolated from newly grown host tissues, but cause necrotic lesions as the plant moves into a reproductive phase. Cultivated hosts in which this form of infection has been studied include Hemerocallis (Grant-Downton et al., 2014), hybrid commercial Primula (Barnes and Shaw, 2002, 2003), and lettuce (Sowley et al., 2010). In wild-growing plants, Rajaguru and Shaw (2010) found widespread infection in leaves of Taraxacum and, to a lesser extent, wild Primula vulgaris. A sampling for endophytes in Centaurea stoebe revealed the frequent occurrence of Botrytis spp., including isolates not derived from known species (Shipunov et al., 2008).

It is becoming increasingly clear that this situation is quite common. A simple distinction between pathogens and non-pathogens may not be possible for many fungal species, as several pathogens have extended cryptic phases (Stergiopoulos and Gordon, 2014). The most obvious examples, and most similar to the Botrytis case, are seedborne smut fungi (Schafer et al., 2010), with a cryptic phase from seed until flower maturation. In a more complex example, isolates of Fusarium oxysporum can cause devastating disease, with individual fungal genotypes often displaying a very narrow host range or be a benign root endophyte (Gordon and Martyn, 1997; Demers et al., 2015), wherein both endophytic and pathogenic behavior appear to be polyphyletic (Gordon and Martyn, 1997).

The discovery of distributed, symptomless infection by Botrytis sp. in a range of hosts suggests that a proportion of inoculum might arise from these sources, and that the fungus may exist for an important part as an endophyte or intimate phyllosphere inhabitant, with conidia only being produced when the host approaches the end of its life-cycle. Understanding this cryptic infection is important for controlling the disease in hosts in which it happens, and for managing disease in other hosts where the cryptic form may serve as an unexpected source of inoculum. In this paper we draw together data on plant species that act as hosts to symptomless distributed infections of Botrytis; how the infection varies over time and location; whether particular fungal clonal lineages are adapted to particular hosts; the fungal species involved; the effect of the infection on the host. The aim of experiments collated here was to explore an unexpected mode of infection by a fungus often considered to be a “model necrotroph.”

Materials and methods

Surface sterilization

Samples of plant tissues were disinfected with 70% ethanol for 1 min followed by 50% solution of bleach (Domestos, Unilever: 5% NaOCl in alkaline solution with surfactants) for 1 min and rinsed three times in sterile distilled water. In early work, sampled tissues were dipped in paraquat before plating to kill the host tissue and encourage pathogen outgrowth. Seed sterilization was carried out by soaking 0.5 g of seed in 100 ml of 0.10 g/l of the systemic fungicide “Shirlan” (active ingredient 500 g/l Fluazinam, Syngenta Crop Protection UK Ltd.) for 2 h and dried overnight before sowing. This was chosen as the most effective and least phytotoxic of a range of fungicides tested.

Isolation and culturing, UK

Sampled tissues were placed on plates of Botrytis selective medium (Edwards and Seddon, 2001). Samples which turned the medium brown were observed under a dissecting microscope after 12 d exposure to 12 h/day daylight + near UV illumination at 18°C. Fungal colonies growing from the samples and showing the characteristic erect, thick, black conidiophores with Botrytis-like conidia were sub-cultured onto malt extract agar.

Isolation and culturing, Netherlands

Botrytis-selective medium was prepared as described by Kritzman and Netzer (1978) with some modifications. The specific composition was (g/l): NaNO3, 1.0; K2HPO4, 1.2; MgSO4.7H2O, 0.2; KCl, 0.15; glucose, 20.0; agar, 15.0. pH was adjusted to 4.5 and the medium sterilized for 20 min at 120°C. After being cooled to 65°C the following ingredients were added (g/l): tetracycline, 0.02; CuSO4, 2.2; p-chloronitrobenzene (PCNB), 0.015; chloramphenicol, 0.05; tannic acid, 5.

Statistical test of clustering

If the frequency of a tissue sample in plant i being infected is pi, the proportion of infected samples on that plant, then a statistic indicating the degree of clustering in a dataset of n plants was calculated as

This weights multiple occurrences strongly. The probability of the degree of clustering observed if infected samples occurred independently was judged by repeatedly randomly allocating the total number of positives seen among the total number of samples, grouping the samples into sets representing the individual plants, and recalculating the statistic above. The observed value was compared with an ordered list of the test statistic calculated on the randomizations.

Sampling sites, host species, and collected plant material

England

The Reading University campus, about 130 ha, includes a substantial area of grassland mown annually for hay, mown amenity lawn, formal gardens, woodland, and a lake. Soils are sandy loam overlying river alluvium. Samples of Taraxacum officinale and Bellis perennis were collected across the campus from mown grassland; Arabidopsis thaliana was collected from cultivated beds across the campus and surrounding urban areas; Tussilago farfara was collected from lake margins. Rubus fruticosa agg and cultivated strawberry were collected from farms near Reading, Brighton and Bath. Further samples of T. officinale and P. vulgaris were collected from meadow areas near Brighton and Bath.

Netherlands

T. officinale plants were sampled in four different sites in Wageningen, representing different ecosystems with distinct soil composition. Sampling sites were located around the Wageningen University campus (surrounded by conventional experimental fields and an organic farm with fruit orchards), Binnenveld along the “Grift” canal (boulder clay, grassland with intensive agricultural activities), the floodplain of the Rhine (river clay, grassland grazed by sheep and occasional mowing) and the “Wageningse Eng” (terminal moraine adjacent to the Rhine, loam and sandy soil, recreational use). From each site 25 symptomless, apparently healthy dandelion plants were collected and stored overnight in a cold room until plating, which was done the next day. Plants were cut into three different parts; two leaves, the stem and the flower head. Each tissue sample was surface sterilized by dipping for 30 s successively in 5% bleach, 50% ethanol, and clean water. The leaves, stem and flower head were cut with clean scissors into pieces of 1 cm, of which 3–5 pieces were placed on Botrytis-selective medium as described above. Cultures were incubated at room temperature for 6 days. Cultures with the morphological characteristics of Botrytis and typical dark-brown color were transferred. A subset of colonies was transferred to fresh medium with lower concentration of CuSO4 (2 mg/L), and again incubated at room temperature for 2 days. A Botrytis-specific immunoassay (Envirologix, Portland, Maine, USA) (Dewey et al., 2008, 2013) was used to verify that cultures represent a Botrytis species.

Genotyping, gene sequencing, and phylogenetic analyses

Nine microsatellite primers (Bc1–Bc7, Bc9, Bc10) for B. cinerea developed by Fournier et al. (2002) were used to genotype isolates randomly sampled from treatments. All isolates were genotyped with all nine primer pairs. The PCR reaction contained 2 μl of water, 5 μl PCR master-mix (Abgene, UK), 1 μl of each forward and reverse primers, and 1 μl of template DNA. The program cycles were: denaturing at 94°C for 3 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, annealing temperatures 50°C, (Bc1, Bc3, Bc6, and Bc9), 53°C (Bc2 and Bc5), or 59°C (Bc4, Bc7, and Bc10), and 72°C for 30 s.

DNA isolation and the amplification of fragments of three house-keeping genes (Heat Shock Protein 60, HSP60; Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase, G3PDH; DNA-dependent RNA Polymerase subunit II, RPB2) were performed as described by Staats et al. (2005). Amplification of three additional genes (G3890, FG1020, MRR1) was performed based on sequences reported by Leroch et al. (2013). Gene fragments were sequenced by Macrogen (Amsterdam, Netherlands), and subsequent phylogenetic analysis was performed as described by Staats et al. (2005).

All primers used for the amplification of microsatellite markers or genes for sequencing are listed in Table S1.

Specific experimental designs

Experiment 1: Cryptic systemic infection in Arabidopsis thaliana

A. thaliana plants were grown in a filtered air flow supplied to individually covered pots in a CE room, with a 16 h light and 8 h dark period. Inside the covers, day-time temperature was 26.5°C and night 18.5°C; relative humidity in day and night ranged between 80 and 85%. Light intensity was 200–250 μmol/m2/s. The plants were watered from below so as to keep the compost just moist: every day up to 2 weeks from sowing then at two-day intervals. Spores were collected from plates of B. cinerea B05.10 using a cyclone collector and serially diluted in talc powder through five stages, each by a factor of 10. Five milligrams of diluted spore dust was dusted on plants 21 days after sowing using a porthole in the top of the plant cover, otherwise kept covered with sticky tape. Controls were dusted with talc powder only. Ten replicates were maintained for each treatment and control. Sampling of plant tissues was done on BSM plates 10 days after inoculation. From each plant, two stem segments (~2 cm), three rosette leaves, two stem leaves, a piece of root (~2 cm long), and two inflorescences were separately sampled as surface disinfected and non-surface disinfected.

Experiment 2: Pathogenicity and host specialization

(A) Isolates ES13 (from lettuce), Gsel G07 (from Senecio vulgaris), Arab A07 (from wild A. thaliana), and Dan D07 (from T. officinale) were inoculated onto detached leaves of A. thaliana, T. officinale, S. vulgaris, T. farfara, and lettuce by placing a 5-mm agar plug of the fungal culture grown on PDA on the adaxial side of a surface sterilized leaf of the host to be tested. The leaf was placed on damp filter paper in 20 × 10 cm plastic boxes with the lid covered. A plug of PDA was used as a control. Ten replicates were made; a single box contained only one type of leaf. Sizes of the necrotic lesion on the leaves were measured after 5 days, as the maximum dimension on asymmetric leaves. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance allowing for the split-plot design. (B) Conidia were harvested from 8 to 10 day old cultures grown on PDA and suspended in sterile water with 0.01% Tween-20 solution, separated by vortex-mixing and adjusted to 1000/μl. Droplets of 5 μl were inoculated on 1 cm2 leaf pieces cut from leaves of lettuce, S. vulgaris, T. farfara, and T. officinale. Infected leaf pieces were counted after 5 days. Results were analyzed using a generalized linear model with Bernouilli error and a logistic transform.

Experiment 3: Pathogenicity and host specialization

Detached leaves of tomato (cv. Moneymaker) or leaves of whole plants of Nicotiana benthamiana and T. officinale (grown from surface-sterilized seeds) were inoculated with 2 μl droplets of conidial suspensions of different Botrytis isolates (106/ml in Potato Dextrose Broth, 12 g/l). Inoculated plant material was incubated in a plastic tray with transparent lid at 20°C in high humidity. Disease development was recorded on consecutive days from 3 to 7 days post inoculation. The proportion of inoculation droplets clearly expanding beyond the site of inoculation was taken as a measure for disease incidence (in %), the diameter of an expanding lesion (in mm) was taken as a measure for disease severity.

Experiment 4: Sporulation and transmission in lettuce

Fungicide seed sterilization was carried out by soaking 0.5 g of seeds in 100 ml of (0.10 g/l) systemic fungicide “Shirlan” (Syngenta) for 2 h and drying overnight before sowing. Seedlings were transplanted to 1 L pots when three true leaves were emerged; in half the pots ten 1 cm plugs of a Trichoderma harzianum T39 culture were placed in the compost at transplanting. A suspension of Botrytis ES13 (105 spores/ml) was sprayed onto half the plants 4 weeks after transplanting. Plants were covered with polythene bags for 24 h to retain high humidity following inoculation. Seed treated and untreated plants were arranged in randomized blocks each containing a replicate of the experiment (±seed sterilization × ±Botrytis inoculation × ±Trichoderma inoculation). At 14 weeks, plants were harvested and samples plated on BSM. Five 1-cm diameter leaf disks from five different leaves, five samples scraped from inside the stem, and five 1-cm long pieces of tap and secondary root system were randomly selected from each test plant. All samples were from healthy tissue with no visual sign or symptoms of damage. Samples were washed under running tap water, then surface sterilized, and placed on BSM to detect Botrytis, as described above.

Experiment 5: Transmission in dandelion

Forty non-sterilized and 40 surface-sterilized seeds of T. officinale (sampled on the river banks of the Rhine) were grown on BSM for 3 days to test whether they were infected by Botrytis. Seeds were then transferred to wet filter paper for a week and 20 selected germinated seedlings were transferred into an autoclaved sand-soil (1:1) mixture. The plants were grown in separate plastic pots for 2 months until they were of sufficient size for infection assays. Symptomless Botrytis infection in T. officinale leaves was monitored before the infection assay was performed. One leaf of each plant was selected, surface sterilized and cultured on a BSM plate. Botrytis outgrowth was evaluated by checking the color change in the medium and subsequent sporulation.

Experiment 6: Effects on host and environmental interactions

Commercially produced lettuce seed cv. “All the Year Round” was germinated in large seed trays. Two weeks later, seedlings were transplanted to 1 L pots of John Innes 2 compost. Thirty seedlings were tested for infection by Botrytis as before; no infection was found. Pots were grouped in sets of four, inoculated or not. A 26 factorial design with treatments inoculation × temperature × shading × nitrogen form was then laid out with six randomized blocks of inoculation × shading × nitrogen form in each glasshouse (192 plants in total). Groups of four pots were shaded using green mesh approximately 30 cm above the pots, draped down the sides. Pots were fertilized twice weekly with either 4 mM KNO3 or 4 mM (NH4)2SO4 +2 mM K2SO4. Thirty-six days after sowing, the pots to be inoculated were moved to a separate glasshouse. They were arranged in trays of 16 and inoculated with dry spores by tapping a plate above the tray, followed by enclosure in black plastic for 30 min to allow spores to settle. At 1, 2, and 3 months after sowing one plant was removed from each set of four and dissected to give 12 tissue samples: edge and central samples from an old leaf, a mature leaf, and a young leaf, three stem and three root samples. These were plated on BSM as before and the presence of Botrytis noted. At the third harvest, both remaining plants were cut at the base and oven-dried before weighing. The weight of the tissues that were removed to test for the presence of Botrytis was negligible. Temperature effects are confounded with glasshouse block effects in this design, but this was unavoidable; differences in nitrogen form are also confounded with sulfate supply, also this was unavoidable. The two compartments had the same aspect, shape and shading patterns, so the largest single difference was temperature.

Results

Host range and prevalence

Botrytis species were frequently isolated from the interior of multiple tissues in apparently healthy hosts of many species (Table 1). Prevalence reached 50% of samples or more (as in T. officinale), but was usually less, and cryptic infections other than in flowers were rare or absent in T. farfara, B. perennis, or P. vulgaris. Prevalence varied substantially from tissue to tissue. Species in which fruit infection is frequently reported did not necessarily harbor latent infection in other tissues of the plant: in R. fruticosa agg. and cultivated strawberries Fragaria × ananassae, leaf infection was not found. There was no clear association with particular plant families in the small sample represented here, nor with perenniality. Repeated surveys are available for the perennial herb T. officinale and the short-lived annual A. thaliana. Prevalence varied substantially from year to year, from place to place and from tissue to tissue (Table 2).

Table 1.

Percentage of samples showing cryptic infection with Botrytis in various host plant species.

| Family | Host species | Growth form | Growing situationa | Locationa | Sample size | Flower sample sizeb | Organ isolated from | Randomly associated? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit or petals | Leaf | Stem | Root | ||||||||

| Asteraceae | Tussilago farfara | Perennial cryptophyte | Lake edge | RU | 45 | 10 | 0c | 0 | 0 | 2 | n/ad |

| Bellis perennis | Perennial herb | Lawn | RU | 55 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | n/a | |

| Gerbera x hybrida | Perennial herb | Indoor crop | RU | 96 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

| Taraxacum officinale complex | Perennial herb | Open grassland, lawn | RU | 107 | 75 | 27 | 29 | 21 | 16 | P < 0.001 | |

| WU | 100 | 100 | 72 | 87 | 72 | –c | n.t.e | ||||

| Cirsium vulgare | Perennial herb | Open grassland | RU | 24 | 18 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0c | P > 0.5 | |

| Senecio vulgaris | Ruderal | Cultivated ground | RU | 82 | 62 | 31 | 37 | 26 | 9 | P = 0.002 | |

| Centaurea scabiosa | Perennial cryptophyte | Wild | RU | 35 | 23 | 22 | 49 | 23 | 21 | P = 0.6 | |

| Achillea millefolium | Perennial herb | Open grassland | RU | 44 | 35 | 56 | 32 | 16 | 11 | P = 0.002 | |

| Brassicacae | Arabidopsis thaliana | Short-lived annual herb | Wild | RU | 66 | 41 | 30 | 48 | 41 | 5 | P < 0.001 |

| Primulacae | Primula vulgaris | Perennial herb | Wild | SE | 382 | – | – | 8 | – | – | n/a |

| Rosaceae | Potentilla fruticosa | Perennial shrub | Landscape planting | RU | 100f | – | – | 8 | 7 | – | P < 0.001 |

| Rubus fruticosa agg. | Perennial climber | Hedges | SE | 219 | 219 | 101 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

| Fragaria × ananassae | Perennial herb | Crop | SE | 203 | 203 | 77 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

RU: grounds of Reading University, UK; SE: several locations across southern England; WU, four locations around Wageningen, NL.

Fruiting structures were not necessarily present in all plants sampled.

0: no infection found; – not sampled.

Test not applicable: infestation found in only one organ per plant.

Not tested.

Three bushes, samples 40, 40, 20. All infections came from the bush with sample size 20.

Table 2.

Percentage of tissue samples of wild-growing Taraxacum officinale complex and Arabidopsis thaliana from which Botrytis could be isolated after surface sterilization, at different locations and years.

| Species | Year | Location | Source | Root % | Leaf % | Stem % | Flower % | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. officinale | 2005–6a | Reading | Cooray | 5 | 6 | –b | – | 100 |

| 2005–6a | Bath | Cooray | 13 | 5 | –b | – | 110 | |

| 2005–6a | Brighton | Cooray | 0 | 4 | –b | – | 132 | |

| 2007–8a | Reading | Shafia | 18 | 29 | –b | 27 | 108 | |

| 2008 | Reading | Thriepland | 17 | 31 | –b | – | (182)c | |

| 2014 | Reading | Emblow | 0 | 1 | –b | 6 | 24 | |

| 2014 | Wageningen | Onland and Hoevenaars | –b | 87 | 72 | 72 | 100 | |

| A. thaliana | 2007–8a | Reading | Shafia | 5 | 50 | 41 | 29 | 66 |

| 2010 | Reading | Shaw | 10 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 | |

| 2013 | Reading | Emmanuel | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 76 | |

| 2014 | Reading | Emmanuel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 22 | |

| 2014 | Reading | Emblow | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

Data were sampled separately in autumn, spring and summer; proportions of samples infested were homogenous (χ2 P > 0.2).

–, not sampled.

From nine seedling families. There were no significant differences between families (χ2-test, P = 0.2).

Evidence for spread in and over a single host: Experiment 1

Published evidence about the spread of Botrytis in a single host is available for cultivated hybrid Primula (Barnes and Shaw, 2003) and lettuce (Sowley et al., 2010). In the majority of host species in which isolations could be made from distinct tissues, multiple isolations from a single plant were more common than expected (Tables 1, 2). A. thaliana that were grown in a sterile air-stream and inoculated as seedlings with dry conidia at low density developed normally and did not show any disease symptoms or evidence of stress. Botrytis could be isolated from multiple tissues, many of which only developed after the time of inoculation (Experiment 1). Isolations were strongly clustered in individual plants, consistent with systemic spread in the plant (Figure 1; randomization test P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Clustering of recovery of B. cinerea B05.10 from surface sterilized tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana grown in a sterile airflow and inoculated with dry spores at the two leaf stage. Each drawing of a plant represents the samples into which it was dissected. B. cinerea was recovered from samples colored red; note the strong clustering of infected samples in individual plants (P < 0.001).

In Cyclamen persicum, inoculation of four plants with a spore suspension followed by enclosure in a plastic bag led to serious necrosis development with abundant sporulation. The plants recovered upon removal of the bags and produced new flushes of leaves and eventually flowered, without further signs of Botrytis. Of 14 seed capsules examined (381 seeds) one capsule yielded two Botrytis infected seeds (out of 47) and a second capsule yielded 56 Botrytis infected seeds (out of 57). The seeds from the other 12 capsules were completely free of Botrytis. Isolations were attempted from leaves, roots, exterior and interior samples from the corms. B. cinerea s.l. was isolated from roots of two plants and the exterior and interior of the corm of two others (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recovery of Botrytis from different tissues of four Cyclamen persica plants cv. Midori earlier inoculated and diseased, but recovered and symptomless at the time of sampling.

| Plant | Root | Flower pedicel | Petal | Leaf | Outer corm | Inner corm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midori White (plant #1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Midori White (plant #2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Midori Scarlet (plant #1) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Midori Scarlet (plant #2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Phylogeny and species variation of internal infections in dandelion

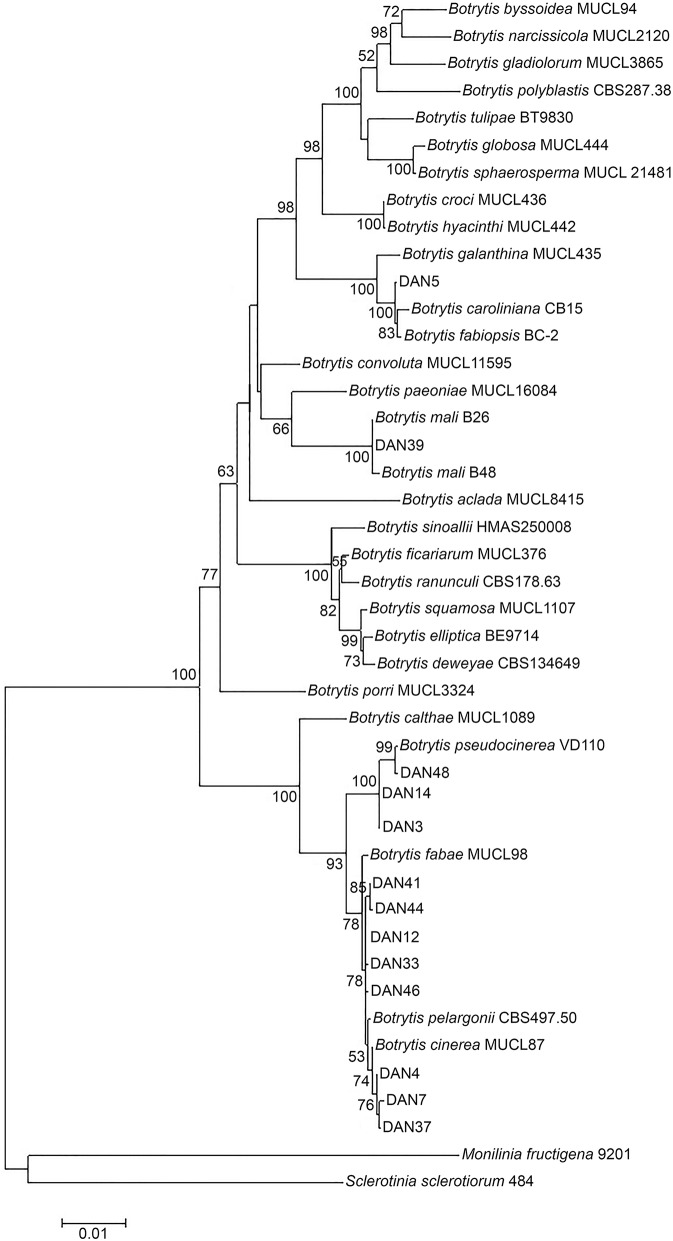

We aimed to test whether strains of Botrytis developing cryptic asymptomatic infection form a separate phylogenetic group, distinct from strains that cause necrotic infections. A preliminary phylogenetic clustering of 47 Botrytis isolates sampled from asymptomatic dandelion in Netherlands was performed based on HSP60 and G3PDH gene sequences (not shown). Thirty-five out of forty-seven isolates grouped with the B. cinerea species complex and 10 grouped with Botrytis pseudocinerea, all members of clade 1 in the genus Botrytis (Staats et al., 2005). Two other isolates grouped into clade 2, i.e., isolates DAN5 and DAN39. Based on this result, eight isolates grouping with B. cinerea and three isolates grouping with B. pseudocinerea, together with the unknown isolates DAN5 and DAN39, were selected for additional analysis of the RPB2 gene sequence. Using as backbone the multiple sequence alignment of 29 known species of the genus Botrytis (Hyde et al., 2014), the concatenated sequences of three genes (HSP60, G3PDH, and RPB2) from the 13 isolates sampled from asymptomatic dandelion were included for phylogenetic tree construction (Figure 2). Eight isolates were related, but not identical, to B. cinerea type isolate MUCL7. Three isolates were related but not identical to B. pseudocinerea isolate VD110. Isolate DAN5 clustered with, but is not identical to, Botrytis caroliniana and Botrytis fabiopsis, while DAN39 clustered very tightly with two Botrytis mali isolates and is probably a member of this species. There was good agreement between phylogenetic trees for individual gene sequences HSP60, G3PDH, and RPB2 (Figures S1–S3). In order to provide a better phylogenetic resolution of isolates that were most closely related to B. cinerea, 16 isolates were analyzed in more detail for the sequences of three additional genes (G3890, FG1020, MRR1; Figures S4–S6). The combined phylogeny for these three genes (not shown) revealed that nine of the 16 isolates were closely related to Botrytis type S, a subgroup of isolates within the B. cinerea complex that was initially predominantly sampled from strawberry and is typified by a characteristic insertion of 21 nucleotides in the MRR1 gene (Leroch et al., 2013). The other seven isolates were closely related to B. cinerea but distinct from both B. cinerea groups N and S (not shown).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic position of 13 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on concatenated HSP60, G3PDH, and RPB2 sequences. Recognized Botrytis species are taken from Hyde et al. (2014). Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Mating type analysis

To investigate the mating type of the 47 isolates sampled from asymptomatic dandelion in Netherlands, PCR reactions were carried out that amplify a gene in the MAT locus (Amselem et al., 2011). Both mating type alleles (MAT1-1 and MAT1-2) were found in similar proportions in the isolates from the B. cinerea species complex and from B. pseudocinerea. In both cases the mating types were present in close to a 1:1 ratio. This observation does not necessarily imply that the isolates are progeny from sexual reproduction but at least they have the possibility of finding compatible mating partners within the same host species. Isolate DAN5 has mating type MAT1-1 and isolate DAN39 has mating type MAT1-2 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of mating types in 47 Botrytis isolates from dandelion, as determined by diagnostic PCR.

| Species | Mating type MAT1-1 | Mating type MAT1-2 |

|---|---|---|

| B. cinerea | 19 | 16 |

| B. pseudocinerea | 5 | 5 |

| DAN5, related to B. caroliniana and B. fabiopsis | 1 | – |

| DAN39, putative B. mali | – | 1 |

Pathogenicity and host specialization

If isolates from asymptomatic plants are distinct from pathogenic strains and unable to cause disease, they would not pose a threat to neighboring plants and especially crops. If such isolates, however, have the capacity to cause necrotic symptoms (given the right circumstances), they could at some point in time strongly increase the risk of disease development, either in the symptomless host, or in neighboring (crop) plants. In the next two experiments we therefore aimed to test the capacity of Botrytis isolates from symptomless plants to cause necrotic symptoms on host species from which they were recovered, as well as on other plant species. Artificial inoculation under laboratory conditions requires a suitable spore density, availability of nutrients, and proper environmental conditions to accomplish necrotic infection. We therefore used standard methods with either mycelium on agar plugs or spore suspensions as inoculum.

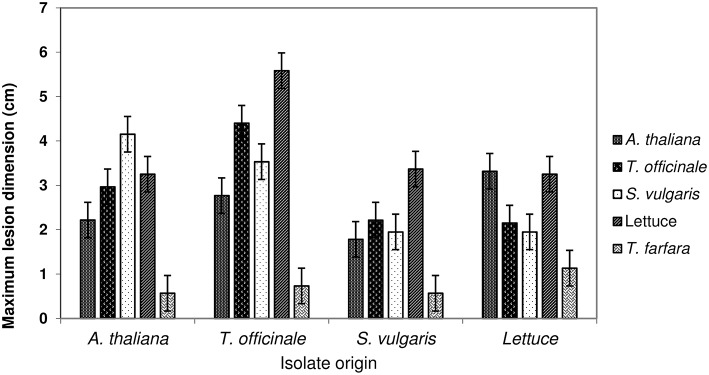

Experiment 2

Isolates sampled from five different host species (A. thaliana, T. officinale, S. vulgaris, T. farfara, and lettuce; one isolate per host origin) were inoculated on newly grown, asymptomatic plants of four host species (the same as above with the exception of T. farfara) in all possible combinations. Inoculations were performed with cultures grown on an agar plug and lesion sizes were monitored (Figure 3). In this test there were differences in virulence (P < 0.001) and in host susceptibility (P < 0.001) and a significant (P = 0.001) but minor interaction between host susceptibility and pathogen virulence in both cases. There was no tendency for isolates to be more pathogenic or less pathogenic on their host of origin. Results were similar when inoculation was performed with spore suspensions.

Figure 3.

Lesion diameters 5 days after agar plug inoculations of isolates of Botrytis sampled from four hosts onto entire detached leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana, Taraxacum officinale, Senecio vulgare, cultivated lettuce, and Tussilago farfara. Error bars represent 1 SED; non-overlapping bars are different at P = 0.05 (uncorrected for multiple comparisons).

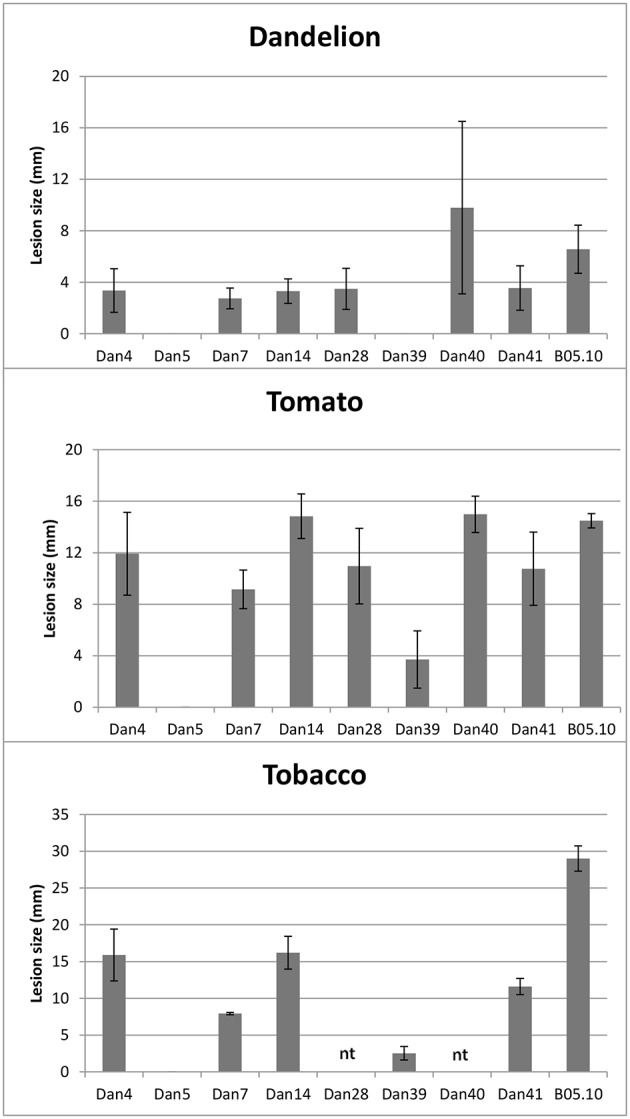

Experiment 3

Eight Botrytis isolates sampled from asymptomatic dandelion in Netherlands were selected for artificial infection assays on leaves of tomato, N. benthamiana and T. officinale plants. Three isolates were selected from the B. cinerea species complex, three were from B. pseudocinerea and the remaining two were isolates DAN5 (related to B. caroliniana and B. fabiopsis) and DAN39 (putative B. mali). As a reference, the commonly aggressive B. cinerea strain B05.10 was always inoculated on the opposite leaf half. Results of these infection experiments are shown in Figure 4. The B. cinerea and B. pseudocinerea isolates all produced expanding lesions on leaves of tomato and N. benthamiana, disease incidence was 100%. On T. officinale leaves, disease incidence for all isolates from asymptomatic dandelion was below 40%, while for B. cinerea strain B05.10 it ranged from 60 to 90%. Isolate DAN5 was entirely unable to cause disease on the three hosts tested. At most it caused small black dots at the inoculation sites, which never developed into expanding lesions at later time points. Isolate DAN39 was able to cause expanding lesions on tomato and N. benthamiana, but not on T. officinale leaves. The lesion diameters differed between isolates and hosts. In general, the diameters of lesions caused by B. cinerea and B. pseudocinerea isolates on tomato leaves were similar to those of strain B05.10, while on N. benthamiana leaves, the lesions were smaller than those of B05.10 (Figure 4). Symptoms on T. officinale leaves were generally few and mild. B. pseudocinerea isolates sampled from symptomless dandelion differed in disease severity on dandelion, the most virulent isolate (DAN40) caused lesions of similar size as those caused by B. cinerea B05.10 whereas the two others (isolates DAN14 and DAN28) caused lesions quite smaller than those of B05.10 (Figure 4). The experiments above show that Botrytis isolates sampled from asymptomatic plant species have the capacity to cause necrotic lesions on the hosts from which they were sampled, as well as on distinct, unrelated plant species.

Figure 4.

Lesion diameter on leaves of Taraxacum officinale at 5 days after inoculation (N = 6), tomato at 3 days after inoculation (N = 8) and N. benthamiana at 3 days after inoculation (N = 3), following inoculation with Botrytis isolates or B. cinerea strain B05.10. Data presented are means with standard deviations indicated with the error bars.

Sporulation, vertical transmission, and closure of the life-cycle

The following experiments were designed to examine whether cryptic infections can be long-lived within a plant and can pass from seeds to mature plants.

Experiment 4, lettuce

This experiment was intended to test the hypothesis that cryptic infection would reduce host growth, and that competing endophytes would reduce this effect. A batch of lettuce seed was used from plants grown outdoors and displaying a 98% frequency of seed infection with B. cinerea. A randomized block full factorial experiment was done with treatments combining seed disinfection with fluazinam, spray inoculation with B. cinerea spore suspension 4 weeks after transplanting (approximately at 10 leaf stage) and compost inoculation with a T. harzianum T39 isolate thought to be a possible biocontrol agent for the internal Botrytis. There were no significant differences in the proportion of plant samples from which Botrytis was recovered (28 ± 3%), so the hypothesis could not be assessed. Only two of the 17 plants from which isolated Botrytis cultures were further characterized displayed symptoms of Botrytis infection. Treatment with T. harzianum neither had a detectable impact on the colonization of the lettuce plants by Botrytis nor on the genotypes recovered from plants exposed to T. harzianum.

To further investigate the results, microsatellite haplotypes were determined from 15 isolates from different tissues of fungicide treated plants and from 13 isolates from untreated plants (Table 5). All the isolates from fungicide untreated plants were identical to each other (haplotype B), but distinct from the isolate used for inoculation (haplotype C). The fungicide treated plants contained six different haplotypes including three recoveries of the inoculated isolate (haplotype C) and a single representative of haplotype B, characterizing the fungicide untreated plants (Table 5; randomization test P < 0.001 against the null hypothesis of random recovery).

Table 5.

SSR genotypes, based on eight loci, of Botrytis isolates recovered from a randomized block factorial experiment on lettuce with treatments of fungicide seed treatment, spray inoculation with isolate ES13 (haplotype C) at the 4-leaf stage and soil inoculation with T. harzianum T39.

| Fluazinam | B. cinerea inoculation | T. harzianum T39 inoculationa | Plant ID | Root | Stem | Leaf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | + | − | 6 | C, C | ||

| 7 | E | |||||

| 17 | Eb | D,Db | ||||

| − | + | 8 | F | |||

| 13 | B | |||||

| 16 | A | |||||

| − | 3 | C,F | ||||

| 4 | A | |||||

| 5 | A | |||||

| − | + | + | 2 | B,B,B,B | ||

| 9 | B,B | |||||

| − | 1 | B,B,B,B | ||||

| 14 | B | |||||

| − | + | 11 | B | |||

| 15 | B | |||||

| − | 10 | B | ||||

| 12 | B |

Letters A–H represent distinct haplotypes found in the Botrytis strains isolated from the host tissue samples.

No samples from the fungicide + T. harzianum + Botrytis inoculation were genotyped.

Symptomatic at time of sampling.

This observation suggests that a pre-existing cryptic infection originating from a seed-borne isolate of Botrytis excluded further infection until an advanced phase of plant growth, and that the level of internal infection sustained was similar regardless of the source of inoculum.

Experiment 5, Taraxacum officinale

Two batches of dandelion plants were grown, one from non-sterilized seeds and the other from surface-sterilized seeds. Placing untreated seeds directly on selective medium established that Botrytis cultures grew out from 100% of the seeds. Both batches of dandelion plants were symptomless throughout their growth. There was no significant difference in the number of leaves or leaf lengths between plants grown from surface-sterilized seeds and the plants grown from untreated seeds (not shown). Botrytis infection in leaves was investigated after 2 months of growth, when plants reached maturity. Botrytis infection was observed in four out of 20 leaves from dandelion plants derived from non-sterilized seeds in the first trial, and 1 out 17 leaves in the second trial. All the plants derived from surface-sterilized seeds were free of Botrytis. The difference is significant at P = 0.02. Therefore, in dandelion, seed infection can survive and grow throughout a proportion of plants until flowering produces the next generation of seed.

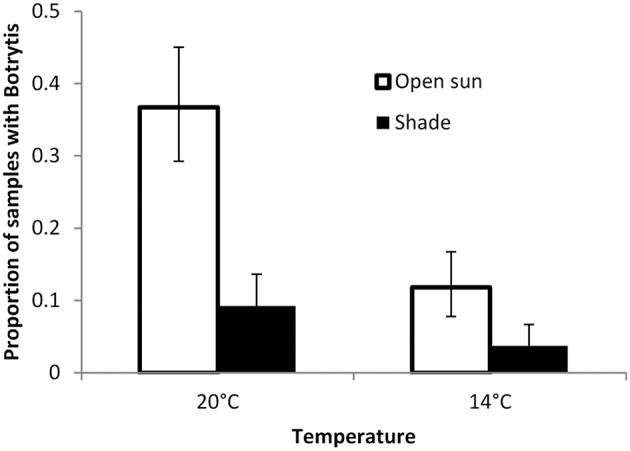

Effects on the host and environmental interactions: Experiment 6

Cryptic infection might impose a defensive load on a host plant. This experiment was designed to test whether factors tending to improve host growth, and thereby reducing resources available for defense, would reduce infection. To measure the effect of cryptic Botrytis infection on growth, commercial seed with a low level of Botrytis contamination was used and half of the plants deliberately dusted with Botrytis spores. Temperature, fertilization and light were varied to produce different growing conditions.

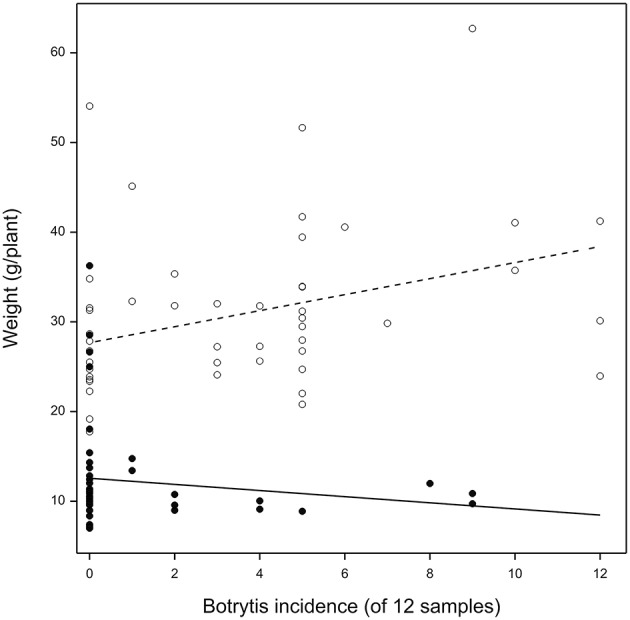

Inoculation of lettuce with Botrytis spores not leading to necrotic infection did not result in changes in the frequency with which Botrytis could be isolated from the plants (factorial anova P = 0.8). Infection frequencies were approximately doubled in unshaded plants compared to plants grown in shaded conditions, and approximately doubled in plants grown at 20°C compared to plants grown at 14°C (Figure 5). Ammonium and sulfate fertilization gave about a 10% relative increase in infection over nitrate fertilization (P = 0.07).

Figure 5.

Proportion of samples of lettuce plant tissue from which Botrytis isolates could be recovered after surface sterilization when grown in shaded or open positions in glasshouse conditions. Back-transformed data from anova on square root transformed data. Error bars are 1 SED.

At final harvest, the Botrytis-inoculated plants were 19% lighter in weight than the uninoculated plants (anova P = 0.02) in unshaded conditions and 23% lighter in weight (anova P = 0.05) in shaded conditions. This result was quantitatively reproducible. The relation between the weight of a lettuce plant and the proportion of Botrytis-infected surface sterilized samples from the same plant depended on whether plants were shaded or unshaded (Figure 6). In unshaded plants there was a weak positive relation between cryptic infection and weight (+ 0.3 percentage points per 1 percentage point increase in infection, P = 0.01). In shaded plants there was a weak and non-significant negative relation (−0.3 percentage points per 1 percentage point increase in infection, P = 0.2).

Figure 6.

Dry weight at harvest (g) of lettuce plants grown in shaded (closed circles) or unshaded (open circles) glasshouse conditions in relation to the number of tissue samples (of 12) from each plant in the experiment (n = 96) from which Botrytis isolates could be recovered after surface sterilization.

This experiment establishes that cryptic infection was not limited by inoculum supply (confirming experiment 4), that conditions favoring host growth, especially light, also favored cryptic infection, and that Botrytis inoculation, despite not altering the final levels of infection, was strongly detrimental to growth.

Discussion

Specialist Botrytis species such as B. aclada and B. allii have been understood to have a life-cycle involving extended periods of symptomless growth (Maude and Presly, 1977; du Toit et al., 2004). Seed infection by species in the B. cinerea complex leading to seedling infection has been well-known for some time in species such as linseed (Harold et al., 1997) because of its contribution to seedling death. It has been less appreciated that long-lived cryptic infection with generalist Botrytis is possible. This has previously been shown in cultivated primula (Barnes and Shaw, 2003) and in lettuce (Sowley et al., 2010). Quiescent infections of a few host cells which give rise to spreading necrosis at fruit maturity are characteristic of many fruit diseases (e.g., Prusky and Lichter, 2007; Puhl and Treutter, 2008). The mode of growth discussed here is different, as it is a form of infection in which the fungus is able to grow with the host and spread to new plant parts. The results above show that many host species growing in natural settings and showing no disease symptoms frequently have disseminated infections of Botrytis species.

This is of both scientific and practical interest. We become increasingly aware that plants harbor many endophytic species (e.g., Shipunov et al., 2008) and that these may have profound effects on their susceptibility to stress and to pathogens (Rodriguez et al., 2009). Understanding that a pathogen like Botrytis, which is investigated mostly in the context of rapidly spreading necrotic infections may also exist as a widespread symptomless infection with minimal effects on the host should seriously alter our understanding of pathogenesis. There are quantitative differences between isolates in their pathogenicity on different species, but we did not obtain any evidence for isolates taken from a particular host to be particularly adapted to that host. Furthermore, both B. cinerea, B. pseudocinerea, and other lineages or cryptic species of Botrytis appeared to occur in this asymptomatic form. From a practical point of view, management of Botrytis in species where cryptic infection is common needs to focus on environmental conditions; it may be ineffective to try to prevent low levels of infection, since permanent cover by systemic fungicide would be needed. In particular, results in lettuce suggest a balanced system in which host defenses are activated sufficiently to prevent infection increasing above a certain density, because plants grown from “clean” seed acquired the same level of infection as plants grown from the infection-carrying seed infection. The question whether cryptic infection is harmful or beneficial to a plant is difficult to address because of the difficulty of growing plants free from Botrytis infection but also in a natural setting.

Because the findings reported may be deemed somewhat surprising, it is important to consider possible artifacts. The most obvious is that these isolations could represent independent, spatially restricted early stages or quiescent infections from environmental conidia. There are several arguments against an important contribution of these artifacts to the observations summarized here. (1) Barnes and Shaw (2003) showed that the sterilization procedure was highly effective in killing adherent spores on seed and other tests with inoculated material have shown the procedure to be effective on leaf tissue. (2) T. officinale and B. perennis grow in the same habitat and often in close proximity but have very different prevalence rates, showing that we are dealing with at least an established association between fungus and host. (3) In greenhouse work, Barnes and Shaw (2003) showed that the same isolate was repeatedly recovered from single hosts, but that adjacent plants rarely hosted identical isolates. This is weak evidence by itself, but supports the hypothesis that this type of infection is at least partially systemic, because it predicts that recovery of isolates or genotypes will be clustered on particular plants. However, clustering can also be ascribed to variation in susceptibility among plants.

Phylogenetic analysis of a subset of isolates sampled from dandelion in Netherlands showed that B. cinerea and B. pseudocinerea were the predominant species. The latter is a recently described species which is morphologically very similar but phylogenetically distinct from B. cinerea (Walker et al., 2011). Based on the morphology of the isolates sampled from a spectrum of plants in the UK, it may be assumed that these also mostly represent B. cinerea and B. pseudocinerea, although this would need extensive sequence analysis to be confirmed. The phylogenetic analysis also identified two isolates of distinct Botrytis species belonging to clade 2 (Staats et al., 2005), one of which (DAN39) is presumably from B. mali, a postharvest pathogen of apple with an as yet poorly explored distribution (O'Gorman et al., 2008). It is perhaps relevant to note that this isolate was sampled from a dandelion plant growing in a grass patch adjacent to an apple and pear orchard of an organic farm. The second isolate from Botrytis clade 2, DAN5, was related but not identical to B. caroliniana and B. fabiopsis, and might represent a novel Botrytis species. An earlier study by Shipunov et al. (2008) on endophytic fungi in Centaurea stoebe identified, besides B. cinerea, six distinct phylogenetic groups of Botrytis isolates. Four of these groups were closely related to B. cinerea and one of them might represent B. pseudocinerea (which had not yet been described at the time of the study by Shipunov et al., 2008). The isolates bot079 and bot378 reported in Shipunov et al. (2008), however, were very distant from the clade containing B. cinerea and grouped with B. paeoniae, alike the B. mali isolate DAN39. Unfortunately the isolates from C. stoebe are no longer available for further phylogenetic comparison (A. Shipunov, personal communication). The above results and those of Shipunov et al. (2008) demonstrate that several new Botrytis species can be retrieved as endophytes from a single host in a limited sampling. A more extensive phylogenetic analysis of Botrytis isolates from multiple hosts and locations would likely reveal many more novel species. If more extensive sampling and further phylogenetic analysis would indeed confirm a greater diversity of Botrytis species than previously appreciated (Staats et al., 2005; Hyde et al., 2014), it raises the question as to how many times the cryptic life-style has arisen.

As with all endophytic organisms, the question arises as to how the host defense system and the pathogen are interacting (Schulz and Boyle, 2005; Newton et al., 2010). There are a number of possibilities. First, the fungus may evade the host defense system by not producing signals which activate defenses strongly enough to destroy the fungus. This is consistent with the increased infection frequency in unshaded lettuce plants in experiment 6: rapidly photosynthesizing plants are likely to have more nutrients in the apoplast, and thus allow more pronounced growth if they do not also have better defense. It is likely that Botrytis produces little or no phytotoxic metabolites and proteins, or plant cell wall degrading enzymes, while it displays symptomless internal infection behavior. If it did produce such compounds, as Botrytis “normally” does (reviewed by van Kan, 2006), this would result in irreversible damage to plant cells and culminate in disease symptoms. It remains elusive why Botrytis does not produce such damaging compounds during cryptic infection. Is it by lack of a (plant-derived) signal to activate the expression of the genes, or is the plant actively suppressing the expression of virulence genes?

An alternative view of the interaction is that host defense continually destroys Botrytis locally, but establishment in new areas is frequent enough to maintain the fungus associated with the plant. In experiment 6, spray inoculation with B. cinerea spores incurred a 20% reduction in growth, without altering infection density. This reduction in growth might reflect the cost of effective defense against a forceful attack; this defense evidently does not alter the balance between systemic infection and host defense. The similarity in frequency of cryptic infection in plants which did and did not have seed-borne infection removed by fungicide in experiment 5 again points to a balanced system in which too much local growth can be eliminated by the host. The hypothesis of a balanced growth/elimination system implies that previously infested plant tissues might become uninfested, as well as the reverse. We have no data on this. Experiments to address this question would be complex because of the destructive nature of current methods to detect infection.

The spore density at the point of first encounter is likely a crucial determinant in whether the interaction becomes asymptomatic or necrotic. At high spore density, and in the presence of nutrients, the fungus can rapidly and efficiently germinate (van den Heuvel, 1981) and produce a spectrum of phytotoxic metabolites and proteins at sufficient concentrations to cause death of multiple plant cells (van Kan, 2006) and set necrotic development in motion. Causing host cell death is in essence a physiologically irreversible decision, although there are cases where primary necrotic lesions fail to develop into an expanding lesion, possibly due to an effective restriction of the fungus by the host (Benito et al., 1998; Coertze and Holz, 2002). In order to achieve symptomless Botrytis infection in plants in our experiments, it was important to start the infection with a low inoculum dosage. The low number of spores and concomitant low density of germlings on the plant surface might not release sufficient phytotoxic metabolites and proteins to activate the plant cell death machinery, and thereby fail to kill cells that would act as an entry point for the fungus. Failure to induce cell death would force the fungus to enter the plant through natural openings and grow in the plant interior where it can retrieve nutrients. The growth of the fungus inside the plant would need to remain restricted and be synchronized with that of the host, possibly by mechanisms similar to those reported for Epichloë endophytes(Tanaka et al., 2012).

A final possible view of the interaction in this system is that the infection is in some circumstances beneficial to the host plant, so that specific signals from Botrytis lead to over-riding of normal defense signals. A hint that this might be so is given by the positive relation between lettuce growth and the frequency with which Botrytis could be recovered from the plants in experiment 7, presumably representing the density of infection. The nature of such signaling processes can only be conjectured at present. Recent studies by Weiberg et al. (2013) described how small RNAs of Botrytis cinerea can actively silence host genes that are involved in immunity, and thereby promote virulence of the pathogen. Conversely, it is conceivable that small RNAs from a host plant could silence Botrytis genes that are required for the activation of virulence mechanisms, and so prevent the production of damaging fungal proteins and metabolites. In the fungal grass endophyte Epichloë, the symbiotic interaction depends on an intact reactive oxygen signaling and MAP kinase signaling. The disruption of components of either of these signaling processes results in breakdown of symbiosis and switch to disease development (Tanaka et al., 2012).

The economic importance of this form of infection could be considerable in a susceptible crop such as lettuce, cyclamen or Primula × polyantha in which persistent infections last for the lifetime of the crop, causing disease and loss at maturity or after harvest. The importance of the demonstration of a large reservoir of infested vegetation in the wider environment depends mainly on how much inoculum it supplies. If this is sufficiently low, there could be no economic implications. On the other hand, given the number of plant species shown to harbor infection, infections in natural vegetation could be an important source of conidia into otherwise clean protected environments. It is less clear what could be done about it, but it suggests that effective integrated management of Botrytis should assume that inoculum is present not only in the air but probably latent in the crops. The best management strategies will focus on the physiological state of the plant and the intrinsic resistance or tolerance of the host to necrotic disease development.

If we can understand the mechanism that determines whether the interaction becomes symptomless or necrotic, it might be possible to steer the interaction in one or other direction, by modifying the environmental conditions, or by applying chemicals that trigger a switch in lifestyle. This might result in active suppression of necrotic development of Botrytis, or in the forced interruption of the symptomless infection.

Author contributions

MS and JvK coordinated the sampling, designed and supervised the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. CE, DE, RT, AS, DT, and ME performed the experiments. CE prepared Figure 1, RT prepared Figure 2, DE prepared Figure 4.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

A substantial contribution to this work was made by Anuja Rajaguru, who sadly died before the preparation of this paper. The authors acknowledge funding from the Commonwealth Studentships Commission, the Gatsby Foundation, the UK Department of Food and Rural Affairs, the Ministry of Education of Malaysia, the Universiti Putra Malaysia, and the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. The authors are grateful to Alice Vanden Bon for expert technical assistance. The authors are grateful to Wageningen University students Violeta Onland, Koen Hoevenaars, and Elisabeth Yánez Navarrete for sampling and preliminary characterization of isolates from dandelion, as well as to prof. Matthias Hahn (Univ, Kaiserslautern, Germany) for fruitful discussion about the phylogenetic analysis. The authors are grateful to Dr. D. O'Gorman, Dr. G. Bakkeren, and Dr. J. R. Úrbez Torres from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Summerland, British Columbia, Canada, for providing the DNA samples of Botrytis mali.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00625

Phylogenetic position of 47 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on HSP60 sequences. Sequences of recognized Botrytis species are taken from Hyde et al. (2014), sequences from B. mali were determined by O'Gorman et al. (2008), the sequence of isolate BOT079 was determined by Shipunov et al. (2008). Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 47 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on G3PDH sequences. Sequences of recognized Botrytis species are taken from Hyde et al. (2014), sequences from B. mali were determined by O'Gorman et al. (2008). Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 13 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on RPB2 sequences. Sequences of recognized Botrytis species are taken from Hyde et al. (2014), sequences from B. mali were determined by O'Gorman et al. (2008). Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 16 Botrytis cinerea isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on G3890 sequences. B. cinerea strain B05.10 serves as the reference and B. calthae strain MUCL2830 was used as an outgroup. Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 16 Botrytis cinerea isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on FG1020 sequences. Sequences from B. cinerea strain B05.10 and B. pseudocinerea strain VD110 (determined by Leroch et al., 2013) serve as the reference while B. calthae strain MUCL2830 was used as an outgroup. Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 14 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on MRR1 sequences. Sequences from B. cinerea strain B05.10, Botrytis N11SE08 and B. pseudocinerea strain VD256 (determined by Leroch et al., 2013) serve as the references. Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Sequences of primers used in this study.

References

- Amselem J., Cuomo C. A., van Kan J. A. L., Viaud M., Benito E. P., Couloux A., et al. (2011). Genomic analysis of the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002230. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S. E., Shaw M. W. (2002). Factors affecting symptom production by latent Botrytis cinerea in Primula x polyantha. Plant Pathol. 51, 746–754. 10.1046/j.1365-3059.2002.00761.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S. E., Shaw M. W. (2003). Infection of commercial hybrid primula seeds by Botrytis cinerea and latent disease spread through the plants. Phytopathology 93, 573–578. 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.5.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito E. P., ten Have A., van 't Klooster J. W., van Kan J. A. L. (1998). Fungal and plant gene expression during synchronized infection of tomato leaves by Botrytis cinerea. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 104, 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Boff P., Kastelein P., de Kraker J., Gerlagh M., Köhl J. (2001). Epidemiology of grey mould in annual waiting-bed production of strawberry. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 107, 615–624. 10.1023/A:1017932927503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boulard T., Chave M., Fatnass H., Poncet C., Roy J. C. (2008). Botrytis cinerea spore balance of a greenhouse rose crop. Agric. For. Meteorol. 148, 504–511. 10.1016/j.agrformet.2007.11.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coertze S., Holz G. (2002). Epidemiology of Botrytis cinerea on grape: wound infection by dry, airborne conidia. South Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 23, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Demers J. E., Gugino B. K., Jimenez-Gasco M. D. (2015). Highly diverse endophytic and soil Fusarium oxysporum populations associated with field-grown tomato plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 81–90. 10.1128/AEM.02590-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey F. M., Hill M., DeScenzo R. (2008). Quantification of Botrytis and laccase in winegrapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 59, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey F. M., Steel C. C., Gurr S. J. (2013). Lateral-flow devices to rapidly determine levels of stable Botrytis antigens in table and dessert wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 64, 291–295. 10.5344/ajev.2012.12103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dik A. J. (1992). Interactions among fungicides, pathogens, yeasts, and nutrients in the phyllosphere, in Microbial Ecology of Leaves, eds Andrews J. H., Hirano S. S. (New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; ), 412–429. [Google Scholar]

- du Toit L. J., Derie M. L., Pelter G. Q. (2004). Prevalence of Botrytis spp. in onion seed crops in the Columbia basin of Washington. Plant Dis. 88, 1061–1068. 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.10.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. G., Seddon B. (2001). Selective media for the specific isolation and enumeration of Botrytis cinerea conidia. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 32, 63–66. 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2001.00857.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elad Y., Pertot I., Cotes Prado A. M., Stewart A. (2015). Plant hosts of Botrytis spp., in Botrytis – The Fungus, The Pathogen and Its Management in Agricultural Systems, eds Fillinger S., Elad Y. (Cham: Springer International Publishing Switzerland; ), 413–486. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier E., Giraud T., Loiseau A., Vautrin D., Estoup A., Solignac M., et al. (2002). Characterization of nine polymorphic microsatellite loci in the fungus Botrytis cinerea (Ascomycota). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2, 253–255. 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2002.00207.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T. R., Martyn R. D. (1997). The evolutionary biology of Fusarium oxysporum. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 35, 111–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant-Downton R. T., Terhem R. B., Kapralov M. V., Mehdi S., Rodriguez-Enriquez M. J., Gurr S. J., et al. (2014). A novel Botrytis species is associated with a newly emergent foliar disease in cultivated Hemerocallis PLoS ONE 9:e89272. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold J. F. S., Fitt B. D. L., Landau S. (1997). Temperature and effects of seed-borne Botrytis cinerea or Alternaria linicola on emergence of linseed (Linum usitatissimum) seedlings. J. Phytopathol. 145, 89–97. 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1997.tb00369.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hausbeck M. K., Moorman G. W. (1996). Managing Botrytis in greenhouse-grown flower crops. Plant Dis. 80, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde K. D., Nilsson R. H., Alias S. A., Ariyawansa H. A., Blair J. E., Cai L., et al. (2014). One stop shop: backbones trees for important phytopathogenic genera: I. Fungal Divers. 67, 21–125. 10.1007/s13225-014-0298-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerssies A., Bosker-van Zessen A. I., Wagemakers C. A. M., van Kan J. A. L. (1997). Variation in pathogenicity and DNA polymorphism among Botrytis cinerea isolates sampled inside and outside a glasshouse. Plant Dis. 81, 781–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzman G., Netzer D. (1978). Selective medium for isolation and identification of Botrytis spp. from soil and onion seed. Phytoparasitica 6, 3–7. 10.1007/BF02981180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leroch M., Plesken C., Weber R. W. S., Kauff F., Scalliet G., Hahn M. (2013). Gray mold populations in German strawberry fields are resistant to multiple fungicides and dominated by a novel clade closely related to Botrytis cinerea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 159–167. 10.1128/AEM.02655-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude R. B., Presly A. H. (1977). Neck rot (Botrytis allii) of bulb onions. Ann. Appl. Biol. 86, 163–180. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1977.tb01829.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McQuilken M. P., Thomson J. (2008). Evaluation of anilinopyrimidine and other fungicides for control of grey mould (Botrytis cinerea) in container-grown Calluna vulgaris. Pest Man. Sci. 64, 748–754. 10.1002/ps.1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton A. C., Fitt B. D. L., Atkins S. D., Walters D. R., Daniell T. J. (2010). Pathogenesis, parasitism and mutualism in the trophic space of microbe–plant interactions. Trends Microbiol. 18, 365–373. 10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Gorman D. T., Sholberg P. L., Stokes S. C., Ginns J. (2008). DNA sequence analysis of herbarium specimens facilitates the revival of Botrytis mali, a postharvest pathogen of apple. Mycologia 100, 227–235. 10.3852/mycologia.100.2.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusky D., Lichter A. (2007). Activation of quiescent infections by postharvest pathogens during transition from the biotrophic to the necrotrophic stage. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 268, 1–8. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00603.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl I., Treutter D. (2008). Ontogenetic variation of catechin biosynthesis as basis for infection and quiescence of Botrytis cinerea in developing strawberry fruits J. Plant Dis. Protect. 115, 247–251. 10.1007/BF03356272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaguru B. A. P., Shaw M. W. (2010). Genetic differentiation between hosts and locations in populations of latent Botrytis cinerea in Southern England. Plant Pathol. 59, 1081–1090. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02346.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R. J., White J. F., Jr., Arnold A. E., Redman R. S. (2009). Fungal endophytes: diversity and functional roles. New Phytol. 182, 314–330. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02773.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer A. M., Kemler M., Bauer R., Begerow D. (2010). The illustrated life cycle of Microbotryum on the host plant Silene latifolia. Botany 88, 875–885. 10.1139/B10-061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz B., Boyle C. (2005). The endophytic continuum. Mycol. Res. 109, 661–686. 10.1017/S095375620500273X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipunov A., Newcombe G., Raghavendra A. K. H., Anderson C. L. (2008). Hidden diversity of endophytic fungi in an invasive plant. Am. J. Bot. 95, 1096–1108. 10.3732/ajb.0800024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowley E. N. K., Dewey F. M., Shaw M. W. (2010). Persistent, symptomless, systemic, and seedborne infection of lettuce by Botrytis cinerea. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 126, 61–71. 10.1007/s10658-009-9524-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staats M., van Baarlen P., van Kan J. A. L. (2005). Molecular phylogeny of the plant pathogenic genus Botrytis and the evolution of host specificity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 333–346. 10.1093/molbev/msi020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stergiopoulos I., Gordon T. R. (2014). Cryptic fungal infections: the hidden agenda of plant pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 5:506. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A., Takemoto D., Chujo T., Scott B. (2012). Fungal endophytes of grasses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 462–468. 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel J. (1981). Effect of inoculum composition on infection of French bean leaves by conidia of Botrytis cinerea. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 87, 55–64. 10.1007/BF01976657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Kan J. A. L. (2006). Licensed to kill: the lifestyle of a necrotrophic plant pathogen. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 247–253. 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. S., Gautier A., Confais J., Martinho D., Viaud M., Le Pecheur P., et al. (2011). Botrytis pseudocinerea, a new cryptic species causing gray mold in French vineyards in sympatry with Botrytis cinerea. Phytopathology 11, 1433–1445. 10.1094/PHYTO-04-11-0104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiberg A., Wang M., Lin F. M., Zhao H. W., Zhang Z. H., Kaloshian I., et al. (2013). Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science 342, 118–123. 10.1126/science.1239705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic position of 47 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on HSP60 sequences. Sequences of recognized Botrytis species are taken from Hyde et al. (2014), sequences from B. mali were determined by O'Gorman et al. (2008), the sequence of isolate BOT079 was determined by Shipunov et al. (2008). Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 47 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on G3PDH sequences. Sequences of recognized Botrytis species are taken from Hyde et al. (2014), sequences from B. mali were determined by O'Gorman et al. (2008). Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 13 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on RPB2 sequences. Sequences of recognized Botrytis species are taken from Hyde et al. (2014), sequences from B. mali were determined by O'Gorman et al. (2008). Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 16 Botrytis cinerea isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on G3890 sequences. B. cinerea strain B05.10 serves as the reference and B. calthae strain MUCL2830 was used as an outgroup. Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 16 Botrytis cinerea isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on FG1020 sequences. Sequences from B. cinerea strain B05.10 and B. pseudocinerea strain VD110 (determined by Leroch et al., 2013) serve as the reference while B. calthae strain MUCL2830 was used as an outgroup. Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Phylogenetic position of 14 Botrytis isolates from asymptomatic dandelion (labeled by DAN and a number) in the genus based on MRR1 sequences. Sequences from B. cinerea strain B05.10, Botrytis N11SE08 and B. pseudocinerea strain VD256 (determined by Leroch et al., 2013) serve as the references. Phylogenetic tree construction used a maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. Only bootstrap values higher than 50% are displayed at the nodes.

Sequences of primers used in this study.