Abstract

Next-generation molecular devices and machines demand the integration of molecular switches into hierarchical assemblies to amplify the response of the system from the molecular level to the meso- or macro-scale. Here, we demonstrate that multi-azobenzene oligomers can assemble to form robust supramolecular nanofibers in which they can be switched repeatedly between the E- and Z-configuration. While in isolated oligomers the azobenzene units undergo reversible photoisomerization independently, in the nanofibers they are coupled via intermolecular interactions and switch cooperatively as evidenced by unusual thermal and kinetic behavior. We find that the photoisomerization rate from the Z-isomer to the E-isomer depends on the fraction of Z-azobenzene in the nanofibers, and is increased by more than a factor of 4 in Z-rich fibers when compared to E-rich fibers. This demonstrates the great potential of coupling individual photochromic units for increasing their quantum efficiency in the solid state with potential relevance for actuation and sensing.

Synthetic photoresponsive molecules can be used as building blocks for a large variety of emerging applications ranging from molecular sensors1, energy2 and information3 storage devices to nano-optomechanical devices such as molecular motors4,5,6,7,8,9,10, artificial muscles11,12 and photoactuators13,14. For enabling these applications it is important to convert molecular nanoscale events into measurable effects at meso- and macro-scales by integrating molecular switches into well-defined hierarchical assemblies15,16,17. This can be achieved by both covalent bonding of monomeric switching units to form photoresponsive oligomers or polymers as well as their supramolecular assembly.

Within these densely packed supramolecular systems, it is important to control and, ideally, leverage the intra- and intermolecular interaction between switching units, because steric interaction, as well as excitonic and electronic coupling between adjacent molecular switches, alter the switching process18. Too strong coupling can completely suppress the photoresponse, both via simple steric hindrance or via excitonic coupling leading to delocalization of the excitation before the energy can be transferred to the nuclear coordinates19,20. However, coupling within a supramolecular assembly can also lead to positive cooperativity, that is, the chromophores do not switch independently from each other but exhibit emergent behavior, e.g., by supporting switching cascades21,22,23. In biological systems, such cooperativity is commonly used to accelerate specific processes and to increase or amplify the outcome of reactions24.

In synthetic photoresponsive systems, it is an interesting question, if cooperative interaction between molecular switches could be used to amplify the impact of individual photoisomerization events. Ultimately, an array of cooperatively coupled molecular switches could act as a molecular amplifier that magnifies the power of an input signal at the nanoscale, such as absorption of a single photon, or a molecular recognition event into an output signal at the macroscopic scale, e.g., by releasing stored internal energy corresponding to the energetic difference between two switching states. Possible applications include sensing devices, where cooperativity could be used to amplify single-molecule events at the nanoscale to readily measurable effects involving many molecules and thus to increase the sensitivity25,26.

However, there are only very few reports of artificial systems exhibiting cooperative switching, yet27,28,29. One problem is to design molecular systems in which the intermolecular coupling is not so strong as to impede reversible switching but strong enough to make the isomerization dependent on neighboring molecules. Azobenzene derivatives in particular are promising building blocks for cooperatively switching multicomponent molecular systems. This is because the isomerization from the stretched out E-isomer to the compact Z-isomer is accompanied by significant changes of geometry and dipole moment, which enables neighboring chromophores to interact during isomerization through steric or electronic coupling. Azobenzene polymers incorporating multiple covalently bonded azobenzenes in their main chain exhibit contractile motion upon UV-irradiation30,31. Recently, we developed a rigid rod polymer (P1) that incorporates more than 30 azobenzene units in its poly(p-phenylene)s (PPP) backbone32,33,34. The introduction of large dihedral angles in the P1 backbone makes sure that the azobenzenes along the polymeric chain are electronically decoupled and photoisomerize with high efficiency35.

In this work, we show that azobenzene oligomers of type P1 self-assemble into well-defined nanofibers and quantitatively analyze the switching kinetics of these linear, supramolecular assemblies. We find that the Z → E photoisomerization of azobenzenes in P1 nanofibers is significantly slower at elevated temperatures, in contrast to isolated azobenzene oligomers where both thermal and optical Z → E isomerizations are faster at elevated temperatures. Further, we find that in the nanofibers the effective Z → E photoisomerization rate is increased by up to a factor of 4, depending on the fraction of azobenzenes in the Z-configuration. We attribute this to an increased photoisomerization efficiency due to cooperativity among individual switching units36.

Results and Discussion

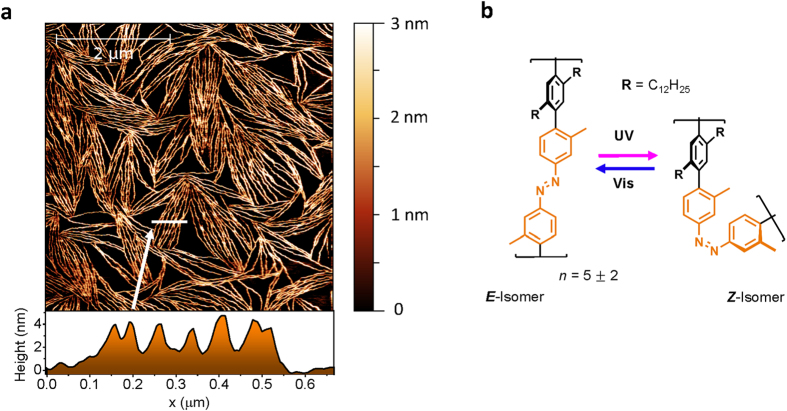

Figure 1a displays an AFM image of a sample of azobenzene oligomers after deposition onto an oxidized silicon wafer via spin coating from a toluene solution. The SiO2 surface is covered by a fibrillar network. Single nanofibers exhibit a characteristic length in the range of 1–2 μm, a height of about 4 nm, and an apparent width of about 20 nm, which, due to the finite radius of the AFM tip (<10 nm)37, corresponds to a real width on the same order as the measured height. The typical spacing between the nanofibers is several 10 nm. Since the length of an isolated oligomer in the thermally stable E-configuration is only around 8 nm, the nanofibers are attributed to supramolecular aggregates consisting of many oligomers. Interestingly, only very few of the nanofibers on the SiO2 surface have a loose end, which indicates the formation of higher order aggregates such as in multiple helices38,39.

Figure 1. Sample morphology and molecular structure of P1.

(a) AFM image showing a 5 × 5 μm2 region of a spin coated sample of P1 oligomers with a height profile. (b) Chemical structure of P1.

For the side-chain alignment we recently demonstrated that, in thin films, P1 polymers can form coherently ordered nanodomains of interdigitating alkyl side-chains. X-ray diffraction measurements performed on a P1 oligomer nanofiber sample, albeit at a higher nominal thickness, show one of the three Bragg reflections of P1 polymers (see the Supplementary Information, Figure S2), indicating some coherent ordering in the nanofibers.

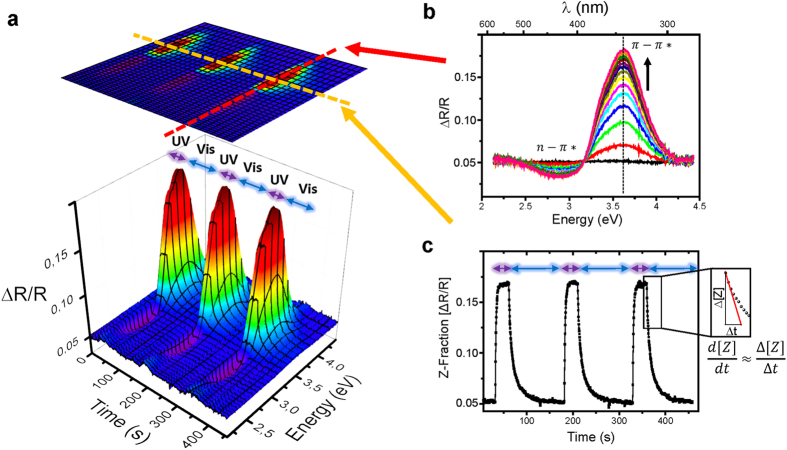

The nanofibers persist even after many switching cycles as we checked with AFM (see the Supplementary Information, Figures S2 and S3). Furthermore, samples measured almost two years after preparation of the film show the same fibrillar structures. These findings underline the robustness of the nanofibers when stored under ambient conditions. Differential reflectance spectroscopy (DRS)40 provides an easy and efficient way to monitor in real-time the conversion of E-azobenzene to Z-azobenzene and vice versa in P1 thin films. DRS measurements demonstrate that the azobenzene chromophores in the thin film can be switched reversibly back and forth with UV light and visible light, respectively. Figure 2a shows a 3D plot of the differential reflectance spectra ΔR/R, that is the change in reflectance divided by the initial reflectance, over time. When the UV LED is switched on for the first time at t = 30 s, the reflectance is increased in the energy range between 3.2 eV and 4.2 eV and is decreased in the energy range between 2.5 eV and 3.2 eV (see Fig. 2b). The increase of the reflectivity, that is positive ΔR/R, around 3.6 eV during E → Z photoisomerization can be rationalized with decreasing absorption in the π − π* absorption band of the E isomer. Conversely, in the region around 2.7 eV, the reflectivity is decreased as the n − π* band of the Z-isomer starts to absorb upon E → Z photoisomerization. Besides these large changes due to the changing fraction of E and Z populations with their respective absorption bands, only a small gradual blue-shift of the individual E-state π − π* and Z-state n − π* bands is observed with DRS, amounting to a total shift of about 10 meV (see SI).After the UV LED is switched off at t = 60 s, the reflectance returns to its initial value before the first UV-irradiation due to the white probe light. Figure 2c shows a cross section through Fig. 2a along the temporal axis at an energy of 3.5 eV.

Figure 2. Differential reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) of P1-nanofibers during photoisomerization.

(a) Reversible switching of an azobenzene nanofiber sample is apparent from a 3D graph of the optical differential reflectance during three switching cycles. Cross sections at fixed time as a function of the energy yield DRS spectra (b) and cross sections at 3.5 eV as a function of time allow for determination of the rate of Z → E isomerization (c).

The photoisomerization kinetics of the azobenzene chromophores can be extracted from the temporal evolution of the differential reflectance. To find the relation between the DRS signal and the photoisomerization kinetics, we simulated the DRS signal of a P1 film on silicon covered with native oxide using the transfer matrix method (see the Supplementary Information, Figure S4)41. Our simulations show that the DRS signal ΔR/R close to the π − π* absorption at 3.5 eV depends linearly on the fraction of Z-azobenzene, that is, the ensemble switching kinetics can be directly inferred from the DRS measurement. A significant amount of roughly 70% of the azobenzenes isomerizes after UV-irradiation with a power density of 110 mW/cm2, according to simulations of the DRS signal using realistic values of the geometry, packing densities and the optical constants of azobenzene in P1 nanofibers (see SI).

The conversion process from Z-azobenzene to E-azobenzene can be described by the following rate equation

|

Here, [E] and [Z] denote the fraction of E- and Z-azobenzene, kEZ denotes the rate constant of the E → Z photoisomerization having contributions from both the UV-part of the Xe-lamp spectrum and the UV LED, and  denotes the Z → E isomerization rate constant of azobenzenes having both thermal contributions and contributions from the Xe-lamp. The thermal contribution to the Z → E isomerization is, however, negligible in comparison with the optical contribution since pure thermal back-switching of azobenzenes typically takes several hours whereas the isomerization process we observe occurs within seconds.

denotes the Z → E isomerization rate constant of azobenzenes having both thermal contributions and contributions from the Xe-lamp. The thermal contribution to the Z → E isomerization is, however, negligible in comparison with the optical contribution since pure thermal back-switching of azobenzenes typically takes several hours whereas the isomerization process we observe occurs within seconds.

The solution of eq. (1) is a monoexponential function with the apparent (effective) isomerization rate  . The effective isomerization rate keff can be determined experimentally from the real-time DRS data via

. The effective isomerization rate keff can be determined experimentally from the real-time DRS data via

|

where  and [Z] are the velocity of the Z → E conversion and the fraction of Z-azobenzene at a certain time and Δ[Z] denotes the absolute difference between the high and low asymptotical level of Z-azobenzene fraction. In the following, we discuss the temperature and light-intensity dependence of the Z → E isomerization rate, that is, the initial decay of the time-dependent Z-azobenzene fraction.

and [Z] are the velocity of the Z → E conversion and the fraction of Z-azobenzene at a certain time and Δ[Z] denotes the absolute difference between the high and low asymptotical level of Z-azobenzene fraction. In the following, we discuss the temperature and light-intensity dependence of the Z → E isomerization rate, that is, the initial decay of the time-dependent Z-azobenzene fraction.

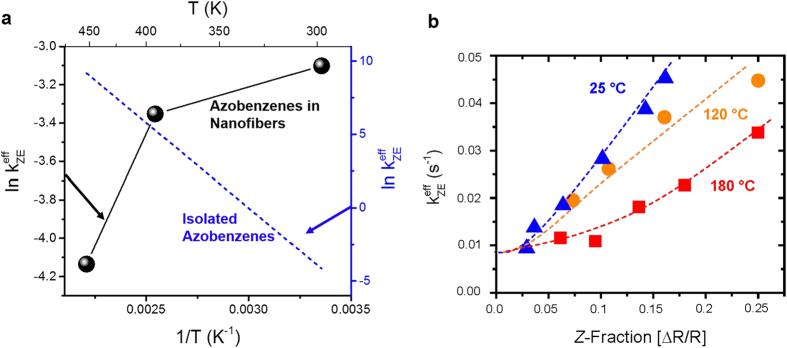

Upon analyzing the kinetics of the Z → E photoisomerization, we find that the azobenzene chromophores in the nanofibers do not switch independently but exhibit cooperativity and a non-Arrhenius-type thermal switching behavior. The first indication is shown in Fig. 3a, where the temperature dependence of the measured effective isomerization rate keff is plotted (see eq. 2). We find that the effective Z → E photoisomerization rate starting from the same fraction of Z-azobenzene decreases with increasing temperature. This behavior is diametrically opposed to the behavior of independently switching azobenzenes in solution, for which the thermal back-reaction across an energetic barrier on the order of 1 eV leads to an increasing keff at higher temperatures42. The dotted line in Fig. 3a shows the typical Arrhenius behavior for a purely thermal process.

Figure 3. Apparent ensemble photoisomerization rates of P1-oligomers for different temperatures.

(a) Arrhenius plot of the rate of the Z → E photoisomerization reaction measured at three different temperatures starting from the same level of Z-azobenzene fraction (≈0.15). The thermal behavior we find is in clear contradiction to the Arrhenius-type behavior of isolated azobenzenes (blue dotted line) that switch faster at higher temperatures. (b) Dependency of the Z → E photoisomerization rate keff on the fraction of Z-azobenzene in the film, plotted for three different temperatures (dotted lines to guide the eye), showing that the isomerization rate also depends on the fraction of Z-azobenzene.

In addition to real-time measurements at different temperatures, we also measured the rate of the Z → E photoisomerization as a function of the starting fraction of Z-azobenzene in the nanofibers at three different temperatures (Fig. 3b). At room temperature, where the effect is the strongest, the effective photoisomerization rate can differ by more than a factor of 4 for different starting fractions of Z-azobenzene. This dependency of the ensemble switching kinetics of the azobenzene units on the isomeric state of the environment directly shows that the azobenzenes in the nanofibers do not switch independently but cooperatively. It is important to note that P1-type multi-azobenzene compounds, which are dissolved in cyclohexane at rather low concentration (≈10−5 mol/L) in order to avoid aggregation, do not switch cooperatively, that is, the individual azobenzene units within a single isolated macromolecule switch independently35.

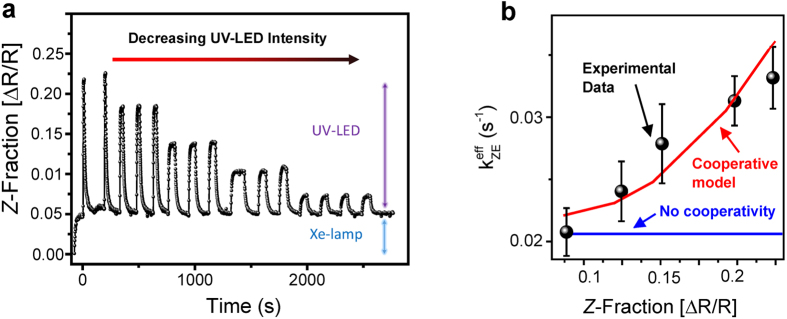

For a quantitative understanding of the cooperativity, we use an intentionally simple model to fit the isomerization kinetics. The real-time kinetics of back-switching from different fractions of Z-azobenzene and the extracted Z-dependent keff that have been used for the fitting are shown in Fig. 4a,b, respectively. Plotted in Fig. 4a is the fraction of Z-azobenzene corresponding to the differential reflectance during several cycles of UV-irradiation at room temperature with varying intensities. In addition, the sample is exposed to white probe light all the time. When the dark sample gets exposed to white probe light of the Xe-lamp, the Z-fraction increases and reaches a steady state. Additional UV-light from the LED (intensity I = 110, 40, 17, 7 and 1.7 mW/cm2 in the range 360 nm–370 nm) further increases the Z-fraction. With a higher LED UV-light intensity, a larger fraction of the azobenzenes is switched from E to Z. After the UV LED is switched off, the Z-fraction returns back to the level corresponding to exclusive irradiation with Xe-light.

Figure 4. Photoisomerization kinetics for different UV-LED intensities.

(a) Differential reflectance at 3.5 eV during several cycles of alternating irradiation with white light + UV light of varying intensities and white light. (b) Experimentally determined Z → E isomerization rates at different photostationary levels together with a simulation including cooperativity (red curve).

For independent azobenzene chromophores, the effective rate of the Z → E back-isomerization  only depends on the spectrum of the Xe-lamp and the temperature and thus would be the same for all switching cycles shown in Fig. 4a. However, our real-time measurements show that the effective Z → E isomerization rate

only depends on the spectrum of the Xe-lamp and the temperature and thus would be the same for all switching cycles shown in Fig. 4a. However, our real-time measurements show that the effective Z → E isomerization rate  is significantly faster in switching cycles where a higher optical output power of the UV LED was used to induce E → Z isomerization. For example, the Z → E isomerization rate after UV irradiation with 110 mW/cm2 is about 50% faster than the Z → E isomerization rate after UV irradiation with 1.7 mW/cm2. The dependency of the back-switching rate on the Z-fraction cannot be described with the simple rate equation for isolated azobenzene moieties (1) because its solution is a monoexponential function with the time- and Z-independent rate

is significantly faster in switching cycles where a higher optical output power of the UV LED was used to induce E → Z isomerization. For example, the Z → E isomerization rate after UV irradiation with 110 mW/cm2 is about 50% faster than the Z → E isomerization rate after UV irradiation with 1.7 mW/cm2. The dependency of the back-switching rate on the Z-fraction cannot be described with the simple rate equation for isolated azobenzene moieties (1) because its solution is a monoexponential function with the time- and Z-independent rate  . A simple modification to the rate equation (1) is to include a linear Z-dependency of the rates. In a first approximation, this introduces a dependency on the isomeric state of the microenvironment. We find that a modification of the E → Z isomerization rate alone cannot explain the observed switching behavior; however, both the kinetics and the photostationary levels of the real-time data can be fitted when modifying the back-switching rate as follows

. A simple modification to the rate equation (1) is to include a linear Z-dependency of the rates. In a first approximation, this introduces a dependency on the isomeric state of the microenvironment. We find that a modification of the E → Z isomerization rate alone cannot explain the observed switching behavior; however, both the kinetics and the photostationary levels of the real-time data can be fitted when modifying the back-switching rate as follows

|

where c denotes a constant.

Inserting eq. (3) into eq. (1) the rate equation model includes cooperative behavior, that is, the Z → E isomerization is faster when there is a higher Z-azobenzene fraction in the film (see Fig. 4b). Note that we did not introduce additional model parameters, even though a refined model could include, e.g., a constant offset to achieve a finite rate at [Z] = 0. According to the modified rate equation, also the E → Z isomerization is faster for higher fractions of Z-azobenzene. However, the deviation from the monoexponential process is significantly smaller for E → Z photoisomerization than in the case of the Z → E photoisomerization, since the contribution of the UV-LED to kEZ dominates eq. (1). In summary, we only need three parameters for the fits to our real-time data: kEZ, c, and a scaling parameter that scales [Z] to the DRS signal ([Z]/(ΔR/R) ≈ 4.1). The red line in Fig. 4b results from a fit of the solution of our modified rate equation to the experimental real-time data in E → Z switching direction for five different UV-intensities and for five corresponding Z → E back-switching processes. The good agreement of our simulation with the measured cooperative kinetics indicates that the linear Z-dependence of the Z → E isomerization rate, indeed, is a good approximation.

Based on the findings of a Z-dependent Z → E isomerization rate in nanofibers, we now discuss the origin of cooperativity, in particular, inter- and intramolecular interactions of the azobenzene chromophores. In principle, intramolecular interactions between azobenzene units can lead to cooperative switching behavior, and other isolated multi-azobenzene derivatives have been shown to exhibit cooperative switching in solution due to π stacking or electronic coupling between azobenzene moieties28. However, in the case of the rigid rod polymer P1 the azobenzene chromophores within a single isolated molecule are electronically decoupled. In an earlier study no signs of cooperative switching have been found for isolated P1-type molecules in extremely diluted cyclohexane solution (≈10−5 mol/L), where no supramolecular aggregates are formed35. For comparison, our nanofiber samples were prepared from a solution with a much higher concentration of about 5 · 10−2 mol/L, whose high absorbance made spectroscopic measurements in solution difficult. In this earlier study, the isolated P1-type molecules exhibited Arrhenius-type thermal behavior and their switching kinetics followed a monoexponential function and thus did not depend on the fraction of Z-azobenzene. This clearly demonstrates that the cooperative behavior of P1-oligomers emerges due to their aggregation into nanofibers.

Intermolecular coupling of P1 azobenzenes in nanofibers is possible, either via mechanical strain, changing free volume or dipole-dipole interactions. In the Z-configuration, azobenzene has a static dipole moment of about 3 Debye while azobenzene in the E-configuration has a dipole moment near zero43. Therefore static dipole-dipole coupling in a sample with a large fraction of Z-azobenzene could influence the back-switching kinetics of Z-azobenzene in the nanofibers. However, the interaction between molecular dipoles of Z-azobenzenes is probably not a dominating effect, because the enhancement starts even at the stages where the Z-azobenzene fraction is very low and the reacting Z-form is most likely to be surrounded by the E-form.

Another possible explanation for the observed enhancement of the effective Z → E photoisomerization rate at higher Z-azobenzene fraction could be an increased number of structural defects in the nanofibers when there are more azobenzenes in the bulky Z-configuration. A greater amount of free volume available to the switching units in the vicinity of defects could lead to a relative acceleration of the photoisomerization rate for a higher Z-azobenzene concentration and thus for a higher defect concentration. However, this theory cannot explain the finding of accelerated Z → E photoisomerization rates at lower temperatures. At higher temperatures beyond the melting temperature of the alkyl side-chain the number of gauge defects and other structural defects among the side-chain should be higher leading to an increased free volume per azobenzene unit. Thus, also the apparent photoisomerization rate should be larger at higher temperatures, which contradicts our experimental observations (see Fig. 3b).

Apart from electrostatic influences and structural defects, it is well known that mechanical strain can influence the isomerization kinetics of azobenzene44. The observed small shifts (Δ ≈ 10 meV) of the Z-form n − π* band around 2.7 eV and the E-from π − π* band around 3.6 eV can be attributed to strain, which varies with the amount of Z-isomer in the surrounding. The strain influence on the spectra is in agreement with the literature for other organic molecular systems45,46.

Tamaoki et al. demonstrated that for bridged bis-azobenzenes the Z → E isomerization is accelerated by orders of magnitude if the Z-isomer is strained47. Turanský et al. performed simulations of the photoinduced Z → E isomerization of stretched azobenzene and found that mechanical stretching can induce Z → E isomerization in the ground state and also favors the photoinduced Z → E isomerization via excited states48,49. These theoretical simulations performed for single azobenzenes can qualitatively explain our experimental findings for azobenzene oligomers in nanofibers. The E → Z isomerization induces steric strain in the nanofibers due to the non-planar geometry of the Z-isomer. Also, the E → Z isomerization of an azobenzene chromophore results in a more twisted, shorter oligomer, which in turn exerts pull along the backbone against forces from interlocked side-chain. Thus, an increase in Z-fraction leads to more strain and a greater mechanical stretching of the switched azobenzenes and therefore can explain the faster, Z-dependent photoinduced back-switching according to the simulations for single azobenzene molecules.

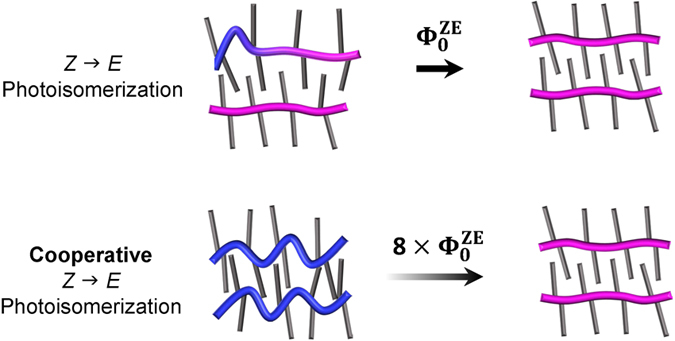

Our second observation of slower back-switching at higher temperatures also can be explained by the temperature dependence of strain. At temperatures above 120–150 °C, roughly corresponding to the melting temperature of polyethylene, ordered alkyl side-chain domains involve more gauche-defects50, thereby decreasing the intermolecular interaction strength of azobenzene chromophores within different oligomers. This weaker coupling reduces the strain and thereby slows down isomerization rates to non-cooperative single molecule levels. An important implication of our findings is that intermolecular cooperativity can be used to increase the quantum yield of photoisomerization (see Fig. 5). According to our kinetic experiments and applying our modified rate equation model, the quantum yield for the Z → E photoisomerization of azobenzenes in the nanofibers can be increased by a factor of 8 (see Supplementary Information). A detailed comparison of the absolute values for quantum yield of P1-oligomers in nanofibers on a surface vs. the quantum yield of isolated P1-oligomers in solution is difficult because of the different experimental techniques and the comparatively large error bars of the optical constants of P1-oligomers in the nanofibers. Our estimate of a Z → E photoisomerization quantum yield ΦZE = 0.16 for high Z-content in the nanofiber indicates that even with positive cooperativity, switching in the nanofibers is slower than for azobenzene in solution, where a Z → E quantum yield (via n − π* excitation) of typically 0.4–0.6 is found51.

Figure 5. Illustration of the proposed switching mechanism.

A higher Z-azobenzene concentration in the nanofibers corresponding to increased strain leads to an 8-fold increase of the quantum yield of photoisomerization  .

.

Theoretically, in multi-component molecular systems that utilize cooperativity it might be possible to raise the quantum yield of Z → E photoisomerization beyond unity, that is, to switch more than one azo-benzene unit with a single photon. While strain accelerates the Z → E photoisomerization, the strain thereby is also released and the cooperativity reduced in our system. Further tuning of the coupling between the chromophores, e.g., by introducing external mechanical strain or by using different coupling mechanisms would be needed to enable a switching cascade. This would be an important step towards a molecular amplifier, that is, a synthetic molecular device that converts input signals corresponding to single-molecule events at the nanoscale into a measurable signal involving many molecules at the macroscopic scale, e.g., by leveraging internal energy, stored in the metastable Z-configuration of azobenzenes.

Conclusions

In this work, we have shown that azobenzene oligomers form nanofibers with well-defined dimensions and shapes, having lengths of 1–2 μm, a height of 4 nm and a typical width on the same order. Whereas in diluted solution, isolated P1-type molecules switch independently, P1 exhibits positive cooperativity when self-assembled into nanofibers. The Z → E isomerization rate depends approximately linearly on the fraction of Z-azobenzene within the film. In contrast to the common Arrhenius-type behavior of isolated molecular switches, the isomerization rate of azobenzenes in the nanofibers is faster at lower temperatures. We attribute this to the temperature dependency of the intermolecular coupling strength of the azobenzene chromophores via side-chain mediated strain. Moreover, we have shown that cooperativity of mechanically interlocked molecular switches can be utilized to increase the efficiency of the Z → E photoisomerization. Our findings are important for next-generation optomechanical devices and highly sensitive molecular sensors based on arrays of molecular switches.

Methods

Materials

The rigid-rod polymer P1 incorporates azobenzene chromophores in a poly(p-phenylene) backbone and has two dodecyl side-chain per monomer (see Fig. 1). A crucial aspect of the design is the presence of ortho-methyl groups and therefore the introduction of large dihedral angles between the azobenzene units in order to decouple these units and break the electronic conjugation. This configuration makes it possible to attain a Z-rich photostationary state (PSS) upon irradiation with UV light. The polymers were synthesized as previously reported. The number average molecular weight Mn was 2900 g mol-1 (corresponding to five repeat units) and the sample had a polydispersity index of 1.45 as determined by GPC vs. polystyrene standards. The azobenzene oligomers can be switched from a thermodynamically stable linear and elongated conformation where the azobenzenes are in the E-configuration to a compact and kinked conformation with azobenzenes in the Z-configuration. Thin films of P1 oligomers were cast from 25 mg/mL solution in toluene onto silicon wafers covered with native silicon oxide. The rotation speed of the bare substrate was set to 1500 rpm before the solution was dispensed.

Measurements and Characterization

AFM measurements were carried out with a NanoWizard III microscope (JPK Instruments AG, Germany). The AFM was operated in air at room temperature in tapping mode with silicon cantilevers (AC240TS, Olympus Corporation, Japan, spring constant 2 N/m). For UV/Vis spectroscopy, we used a setup consisting of a 75 W Xenon Lamp (LOT-QuantumDesign, GmbH, Germany), a fiber with a reflectance probe (LOT-QuantumDesign GmbH, Germany), and a spectrometer consisting of a spectrograph (Acton Series, Princeton Instruments) and a cooled CCD (Andor). All UV/Vis spectroscopy measurements presented in this paper have been performed under atmospheric pressure. E → Z isomerization of P1 was induced with a 365 nm high power UV LED (Thorlabs) with variable optical output and a FWHM of 12 nm. The light-intensity on the sample surface was measured with a thermal power sensor (Thorlabs).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Weber, C. et al. Cooperative Switching in Nanofibers of Azobenzene Oligomers. Sci. Rep. 6, 25605; doi: 10.1038/srep25605 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Generous support by the German Research Foundation (DFG via SFB 658, BL 1269/1-1 and the International Graduate Research Training Group 1524) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.K., S.H. and J.P.R. proposed the research. C.W., T.L., M.G., A.Z. and L.P. carried out the experiments. The organic synthesis was performed by D.B. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

References

- Natali M. & Giordani S. Molecular switches as photocontrollable ‘smart’ receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 4010–4029 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski T. J., Tian Y., Akbulatov S. & Boulatov R. Chemical solutions for the closed-cycle storage of solar energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 4449–4472 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. F., Hashimoto K. & Fujishima A. Photoelectrochemical information storage using an azobenzene derivative. Nature 347, 658–660 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Nakano M. & Ikeda T. Photomechanics: directed bending of a polymer film by light. Nature 425, 145 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka T., Kinbara K. & Aida T. Mechanical twisting of a guest by a photoresponsive host. Nature 440, 512–515 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay E. R., Leigh D. A. & Zerbetto F. Synthetic molecular motors and mechanical machines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 72–191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M. et al. Photomobile polymer materials: towards light-driven plastic motors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4986–4988 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathem B. K., Claridge S. A., Zheng Y. B. & Weiss P. S. Molecular Switches and Motors on Surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 64, 605–630 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenbach A. C. et al. Organic switches for surfaces and devices. Adv. Mater. 25, 331–348 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida E., Azumi R. & Norikane Y. Light-induced crawling of crystals on a glass surface. Nat. Commun. 6, 7310, doi: 10.1038/ncomms8310 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne W. R. & Feringa B. L. Making molecular machines work. Nat. Nanotechnol. 1, 25–35 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun A., Banaszak M., Astumian R. D., Stoddart J. F. & Grzybowski B. A. Great expectations: can artificial molecular machines deliver on their promise? Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 19–30 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juluri B. K. et al. A Mechanical Actuator Driven Electrochemically by Artificial Molecular Muscles. ACS Nano 3, 291–300 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oosten C. L., Bastiaansen C. W. M. & Broer D. J. Printed artificial cilia from liquid-crystal network actuators modularly driven by light. Nat. Mater. 8, 677–682 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abendroth J. M., Bushuyev O. S., Weiss P. S. & Barrett C. J. Controlling Motion at the Nanoscale: Rise of the Molecular Machines. ACS Nano 9, 7746–7768 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klajn R. Immobilized azobenzenes for the construction of photoresponsive materials. Pure Appl. Chem. 82, 2247–2279 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Mathews M. et al. Light-driven reversible handedness inversion in self-organized helical superstructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 18361–18366 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren S. C., Guney-Altay O. & Grzybowski B. A. Responsive and Nonequilibrium Nanomaterials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 2103–2111 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gahl C. et al. Structure and excitonic coupling in self-assembled monolayers of azobenzene-functionalized alkanethiols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1831–1838 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utecht M., Klamroth T. & Saalfrank P. Optical absorption and excitonic coupling in azobenzenes forming self-assembled monolayers: a study based on density functional theory. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 21608–21614 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. B. et al. Photoresponsive molecules in well-defined nanoscale environments. Adv. Mater. 25, 302–312 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik S., De S. & Schmittel M. A trio of nanoswitches in redox-potential controlled communication. Chem. Commun. 50, 13254–13257 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik S., De S. & Schmittel M. Bidirectional Chemical Communication between Nanomechanical Switches. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 53, 4709–4713 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitty A. Cooperativity and biological complexity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 435–439 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsella M. J. & Swager T. M. Designing conducting polymer-based sensors: selective ionochromic response in crown ether-containing polythiophenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 12214–12215 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q. & Swager T. M. Method for enhancing the sensitivity of fluorescent chemosensors: energy migration in conjugated polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 7017–7018 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Pace G. et al. Cooperative light-induced molecular movements of highly ordered azobenzene self-assembled monolayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9937–9942 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z. & Hecht S. Cooperative Switching Events in Azobenzene Foldamer Denaturation. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 10519–10524 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D., Foy J. T., Hughes R. P. & Aprahamian I. A switching cascade of hydrazone-based rotary switches through coordination-coupled proton relays. Nat. Chem. 4, 757–762 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugel T. et al. Single-molecule optomechanical cycle. Science. 296, 1103–1106 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland N. B. et al. Single Molecule Force Spectroscopy of Azobenzene Polymers: Switching Elasticity of Single Photochromic Macromolecules. Macromolecules 36, 2015–2023 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Bléger D. et al. Light-orchestrated macromolecular ‘accordions’: reversible photoinduced shrinking of rigid-rod polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 12559–12563 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C. et al. Light-Controlled ‘Molecular Zippers’ Based on Azobenzene Main Chain Polymers. Macromolecules 48, 1531–1537 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Liebig T., Hecht S., Bléger D. & Rabe J. P. Light-Induced Contraction and Extension of Single Macromolecules on a Modified Graphite Surface. ACS Nano 8, 11987–11993 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bléger D. et al. Electronic decoupling approach to quantitative photoswitching in linear multiazobenzene architectures. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 9930–9940 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekkat Z. & Knoll W. Photoreactive Organic thin Films in the Light of Bound Electromagnetic Waves Ch. 2 (Academic Press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Samorí P., Francke V., Mangel T., Müllen K. & Rabe J. P. Poly-para-phenylene-ethynylene assemblies for a potential molecular nanowire: an SFM study. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 9, 390–393 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher C. et al. Double-helical ultrastructure of polycationic dendronized polymers determined by single-particle cryo-TEM. Chem. - A Eur. J. 11, 2923–2928 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J., Jahnke E., Severin N., Rabe J. P. & Frauenrath H. Consecutive Conformational Transitions and Deaggregation of Multiple-Helical Poly(diacetylene)s. Nano Lett. 8, 1660–1666 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forker R., Gruenewald M. & Fritz T. Optical differential reflectance spectroscopy on thin molecular films. Annu. Rep. Prog. Chem., Sect. C Phys. Chem. 108, 34–68 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard G. F., Hoke E. T. & McGehee M. D. Accounting for interference, scattering, and electrode absorption to make accurate internal quantum efficiency measurements in organic and other thin solar cells. Adv. Mater. 22, 3293–3297 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegiou D., Muszkat K. A. & Fischer E. Temperature dependence of photoisomerization. V. Effect of substituents on the photoisomerization of stilbenes and azobenzenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90, 3907–3918 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann E. & Weizmann A. Dipole Moments as a Tool in the Determination of Structure. Chem. Rev. 29, 553–592 (1941). [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.-Z. et al. A molecular force probe. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 302–306 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzel J., Jankowski S., El Helou M., Witte G. & Heimbrodt W. Temperature dependent optical properties of pentacene films on zinc oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 211102, doi: 10.1063/1.3663863 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. In-situ observation of nucleation processes during organic semiconductor thin film deposition and strain-stabilization of metastable states arXiv:1511.00085 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tamaoki N., Koseki K. & Yamaoka T. [2.2](4,4′)Azobenzenophane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 29, 105–106 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Turanský R., Konôpka M., Doltsinis N. L., Štich I. & Marx D. Optical, mechanical, and opto-mechanical switching of anchored dithioazobenzene bridges. ChemPhysChem 11, 345–348 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turanský R., Konôpka M., Doltsinis N. L., Stich I. & Marx D. Switching of functionalized azobenzene suspended between gold tips by mechanochemical, photochemical, and opto-mechanical means. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 13922–13932 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra S., Iarlori S., Tosatti E., Scandolo S. & Santoro G. Dynamical and thermal properties of polyethylene by ab initio simulation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 331, 339–345 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Dhammika Bandarab H. M. & Burdette S. C. Photoisomerization in different classes of azobenzene. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1809–1825 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.