Abstract

Background

Optimal administration of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), the standard approach for intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), requires clinical and technical expertise. We sought to evaluate if TACE retains its effectiveness when administered across a broad range of healthcare settings. With increasing use of yttrium90 radioembolization (Y90), we explored the effectiveness of Y90 compared with TACE.

Methods

HCC patients diagnosed from 2004–2009 treated initially with TACE or Y90 were identified from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End-Results (SEER)-Medicare linkage. Key covariates included prediagnosis AFP screening, complications of cirrhosis, and tumor extent. Effect of treatment, patient, and healthcare system factors on overall survival (OS) was evaluated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards. Stratified OS estimates are provided. Propensity score (PS) weighting was used to compare effectiveness of Y90 to TACE.

Results

Of 1,528 with intra-arterial embolization, 577 had documentation of concurrent chemotherapy (e.g. TACE). Median OS was 21 months (95% CI 18–23) following TACE, 9 months (95% CI 1–41) following Y90. Refined survival estimates stratified by stage, AFP screening, and liver comorbidity are presented. Ninety day mortality after TACE was 21–25% in patients with extrahepatic spread or vascular invasion. In the PS-weighted analysis, Y90 was associated with inferior survival, aHR 1.39 (95% CI 1.02–1.90).

Conclusions

The effectiveness of TACE is generalizable to Medicare patients receiving care in a variety of treatment settings. However, early post-treatment mortality is high in patients with advanced disease. We found no evidence for improved outcomes with Y90 compared with TACE. Survival estimates from this large cohort can be used to provide prognostic information to patients considering palliative TACE.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of a handful of malignancies with rising incidence and mortality rates in the United States.[1, 2] HCC carries a very poor prognosis, in large part because two thirds of patients have underlying cirrhosis and most have multifocal cancer, both of which limit treatment options.[2, 3] Two intra-arterially delivered locoregional therapy (LRT) options are considered to be reasonable initial therapy for patients with unresectable HCC and compensated cirrhosis: transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and yttrium90 radioembolization (Y90). TACE delivers chemotherapy directly to the cancer through the hepatic arterial system with subsequent arterial embolization, or by the contemporary approach of concurrent chemotherapy delivery and embolization in the form of doxorubicin-eluting beads. Among patients with nonmetastatic HCC and compensated cirrhosis, TACE improves survival over supportive care[4–6] and is widely considered the first-line treatment option.[7] . Bland embolization performed without chemotherapy is used for patients with less compensated cirrhosis at some centers to minimize the risk of the procedure. Bland embolization appears to offer less robust survival benefit.[4]

The optimal delivery of TACE requires considerable clinical expertise to appropriately select patients for therapy and technical expertise for safe and effective administration.[8] Therefore TACE effectiveness might be diminished in centers without ready access to multidisciplinary clinical teams including expert diagnostic and interventional radiology, hepatology, transplant surgery, and oncology. In a prior evaluation of HCC treatment and outcomes using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Medicare linkage of patients treated in the 1990s, outcomes following TACE were quite poor with a median survival of less than a year.[9] A more recent SEER-Medicare analysis of patients treated from 2000–2005 also showed a short median survival, only 14 months.[10] Both of these estimates were well below the quality metric of 20 months proposed by the Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee.[8] However, as the more contemporary analysis excluded patients who underwent ablation, resection, or transplant at any time, only patients with the most advanced disease were evaluated. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the effectiveness of first-line TACE across the spectrum of cancer stages in a contemporary cohort.

Y90-radioembolization, in which either glass or resin microspheres laden with yttrium90 are delivered to cancers through the hepatic arteries, is emerging as an excellent TACE alternative as data emerge reporting survival following Y90 to be comparable to TACE.[11–21] With overlapping clinical indications and similar outcomes, both TACE and Y90 are reasonable initial therapy choices for HCC in a patient with compensated cirrhosis. However, the comparative effectiveness of these procedures as they are being administered throughout the United States is unknown. Therefore using this large observational dataset, we also sought to explore the comparative effectiveness of Y90 versus TACE.

PATIENTS and METHODS

Study Population

The cohort was derived from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Medicare linkage (described in detail elsewhere[22, 23]). We included patients diagnosed with HCC from 2004 to 2009, excluding autopsy diagnoses. To avoid misclassification of liver metastases, patients with prior invasive cancer within 5 years were excluded.[9] To ensure availability of claims, only patients with continuous enrollment in Medicare A and B and patients not enrolled in Medicare Managed Care in the 12 months before and after diagnosis (or death) were included. This analysis was deemed exempt from review by the Office of Human Research Ethics at the University of North Carolina (#12-1828).

Covariates

Sociodemographic patient data, tumor size and number and presence of macrovascular invasion were obtained from SEER (see Supplemental Methods). Laboratory parameters were not available, therefore diagnosis codes for complications of cirrhosis were used to control for confounding liver disease.[24] HCC screening behavior was ascertained by pre-diagnosis AFP[25, 26] as a surrogate measure of performance status as use of cancer screening is associated with decreased probability of frailty in cancer patients.[27] Cause of liver disease was ascertained from claims using ICD-9 diagnosis codes for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, alcoholic cirrhosis, and other cirrhosis. Non-cirrhotic comorbidity was determined using the Klabunde modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).[28] All claims-based covariates were ascertained in the 12 months before diagnosis.

Treating hospital was defined for the majority of patients from inpatient claims on the date of initial procedure. Hospital characteristics were derived from the SEER hospital file. Hospital volume was defined as LRT volume at the treating hospital in the 12 months preceding each individual patient’s treatment.

Treatment

Treatment group was determined by initial therapy delivered. Codes for arterial occlusion without intra-arterial radiotherapy were categorized as embolization (ETable 1); those with codes for chemotherapy or intra-arterial chemotherapy delivery at time of embolization were classified as chemoembolization (TACE) and those without as bland embolization (TAE). Because chemotherapy claims are reliable when present but are less well identified in records of hospitalized patients,[29] some patients receiving chemoembolization were likely misclassified as bland embolization. Because the intent of the procedure cannot be ascertained from claims, some patients classified as TAE may have received embolization for reasons other than anticancer therapy such as to control bleeding from a ruptured tumor or in preparation for Y90-radioembolization that was subsequently aborted. There is not a specific code for drug-eluting beads thus we could not compare specific TACE strategies. Patients with codes for intra-arterial radiotherapy delivery were categorized as receiving Y90regardless of embolization. Because pre-procedure arterial embolization is required to ensure dose and safety of Y90embolization codes in the 60 days before Y90 administration were considered part of Y90.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival (OS) was measured from date of initial procedure until death. Kaplan-Meier methods estimated OS for the entire cohort and within strata of tumor extent, liver comorbidity, and use of pre-diagnosis AFP screening. Cox proportional hazards (PH) models were used to evaluate factors associated with OS. Robust variances were used in all analyses.

As TACE is the standard treatment, we also sought to ask “what would the effect of Y90 be among patients typically treated with TACE” by comparing the effectiveness of Y90 to TACE in a population of patients resembling those selected for initial TAE/TACE. To do so, a weighted pseudo-population was created from the propensity score (PS) for TAE/TACE (see Supplemental Methods).[30] This created treatment groups balanced on key patient characteristics in which multivariable Cox PH models were used to adjust for residual covariate imbalances and OS was compared by treatment. In sensitivity analyses, we compared the effectiveness of Y90 to TAE/TACE after restricting to only those TACE patients with codes for chemotherapy. We also conducted a PS-trimming sensitivity analysis to address the potential for unmeasured confounding by frailty.[31] As patients treated contrary to prediction are most likely to have unmeasured confounding that influences treatment selection (e.g. frailty), omitting them may improve the validity of the treatment effect estimate. If the observed treatment effect were due to unmeasured confounding, it would be expected to approach the null with trimming. Because a larger proportion of TACE patients underwent subsequent curative surgery, sensitivity analysis explored the magnitude of this effect by censoring patients at the time of curative surgery.

RESULTS

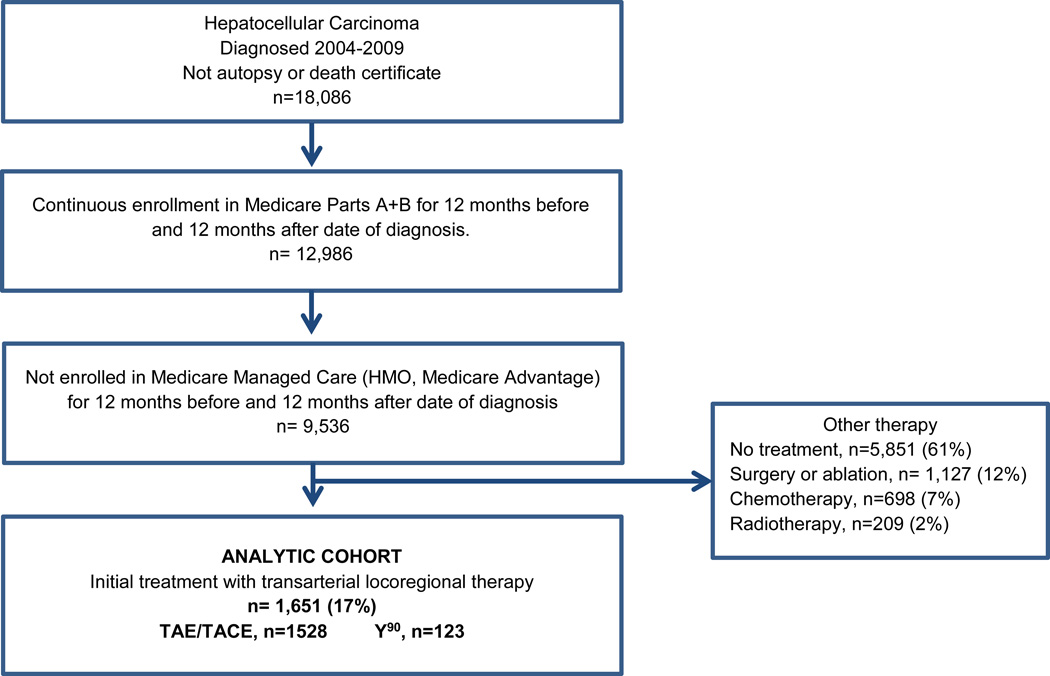

Initial LRT was administered to 1,651 patients, including 1,528 treated with TAE/TACE and 121 with first-line Y90 (Figure 1). Of TAE/TACE patients, 577 (38%) received TACE. Median age of the TAE/TACE group was 72 (range 27–94), 66% of whom were white and 14% Asian (Table 1). The majority of TACE patients had liver-confined unifocal (207, 42%) or multifocal (207, 36%) disease without macrovascular invasion, though 126 (22%) had either macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic disease. Second-line therapy was administered to 1,010 (66%) TAE/TACE patients, including repeat TAE/TACE in 635 (42%), curative surgery in 99 (6%), ablation in 129 (8%), and drug therapy in 104 (7%) (ETable 2). Many second procedures likely represent planned contralateral treatment as 295 of 635 repeat TAE/TACEs occurred within 60 days of first treatment.

Figure 1.

Cohort Assembly

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Association with Survival

| Characteristic | TACE + TAE n=1525 |

TACE n=577 (38%) |

Multivariate HR, 95% CI |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | ||||

| TACE, no chemo code | - | 1 | ||

| TACE, with chemo code | 0.78, 0.69–0.89 | <0.001 | ||

| Median Age (range) | 72 (27–94) | 72 (27–94) | - | - |

| Age | ||||

| < 65 years | 296 (19%) | 108 (19%) | 1 | |

| 65–74 years | 635 (42%) | 259 (45%) | 1.02, 0.85–1.22 | 0.82 |

| 75+ years | 597 (39%) | 210 (36%) | 1.21, 1.00–1.46 | 0.06 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1,045 (68%) | 390 (68%) | 1 | |

| Female | 483 (32%) | 187 (32%) | 1.03, 0.90–1.17 | 0.71 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1,008 (66%) | 374 (65%) | 1 | |

| African American | 136 (9%) | 46 (8%) | 0.94, 0.75–1.18 | 0.60 |

| Asian | 213 (14%) | 92 (16%) | 0.88, 0.68–1.15 | 0.35 |

| Hispanic/Other | 171 (11%) | 65 (11%) | 0.93, 0.75–1.15 | 0.48 |

| Place of Birth | ||||

| USA | 820 (54%) | 278 (48%) | 1 | |

| Asia | 203 (13%) | 85 (15%) | 0.67, 0.51–0.88 | 0.004 |

| Other/Missing^ | 505 (33%) | 214 (37%) | 0.56, 0.49–0.65 | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis B* | 147 (10%) | 72 (12%) | 0.89, 0.70–1.13 | 0.34 |

| Hepatitis C* | 529 (35%) | 211 (37%) | 1.08, 0.94–1.26 | 0.28 |

| Alcohol* | 182 (12%) | 73 (13%) | 0.99, 0.82–1.21 | 0.96 |

| Other* | 127 (8%) | 51 (9%) | 97, 0.77–1.22 | 0.78 |

| Modified Charlson Score | ||||

| 0 | 330 (22%) | 111 (19%) | 1 | |

| 1 | 440 (29%) | 181 (31%) | 1.01, 0.85–1.19 | 0.95 |

| 2+ | 758 (50%) | 285 (49%) | 1.06, 0.90–1.24 | 0.50 |

| # of Cirrhosis Complications | ||||

| 0 | 1161 (76%) | 464 (80%) | 1 | |

| 1 | 240 (16%) | 78 (14%) | 1.37, 1.16–1.62 | <0.001 |

| 2+ | 127 (8%) | 35 (6%) | 1.51, 1.18–1.94 | 0.002 |

| # of Pre-Diagnosis AFP Claims | ||||

| 0 | 639 (42%) | 204 (35%) | 1 | |

| 1 | 456 (30%) | 176 (31%) | 0.79, 0.69–0.92 | 0.002 |

| 2+ | 433 (28%) | 197 (34%) | 0.72, 0.61–0.85 | <0.001 |

| Extent of Tumor | ||||

| Single, no vascular invasion | 639 (42%) | 244 (42%) | 1 | |

| Multiple, no vascular invasion | 503 (33%) | 207 (36%) | 1.34, 1.17–1.54 | <0.001 |

| Single, vascular invasion | 108 (7%) | 38 (7%) | 1.18, 0.93–1.52 | 0.17 |

| Multiple, vascular invasion | 130 (8%) | 48 (8%) | 1.62, 1.30–2.01 | <0.001 |

| Extrahepatic Extension or NOS | 148 (10%) | 40 (7%) | 1.75, 1.40–2.19 | <0.001 |

| Maximum Tumor Size | ||||

| ≤3 cm | 344 (23%) | 150 (26%) | 1 | |

| 3–5 cm | 375 (25%) | 151 (26%) | 1.26, 1.5–1.51 | 0.02 |

| > 5 cm | 568 (37%) | 202 (35%) | 1.81, 1.51–2.16 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 241 (16%) | 74 (13%) | 1.70, 1.36–2.13 | <0.001 |

| Teaching Hospital+ | 1,339 (88%) | 508 (89%) | 1.06, 0.87–1.30 | 0.55 |

| Hospital NCI Designation in 2005 | ||||

| None | 1,202 (80%) | 471 (82%) | 1 | |

| Clinical | 36 (2%) | 18 (3%) | 1.18, 0.78–1.79 | 0.42 |

| Comprehensive | 272 (18%) | 84 (15%) | 0.75, 0.63–0.89 | <0.001 |

| Hospital with Solid Organ Transplant | 1,076 (71%) | 422 (74%) | 0.72, 0.62–0.85 | <0.001 |

| Hospital Volume in Prior 12 months | ||||

| <5 | 802 (52%) | 258 (45%) | 1 | |

| 5–20 | 420 (27%) | 165 (29%) | 0.92, 0.79–1.07 | 0.26 |

| >20 | 306(20%) | 154 (27%) | 0.88, 0.73–1.07 | 0.19 |

TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; AJCC, American Joint Commission on Cancer; NCI, National Cancer Institute; HR, Hazard Ratio. Notes: HR adjusted for variables shown and census track median income, SEER region.

n=360 missing place of birth and n=145 non-US non-Asian born.

Causes are not mutually exclusive. HR referent= no.

Because of missing data, hospital variables do not sum to 1528.

Survival After TACE

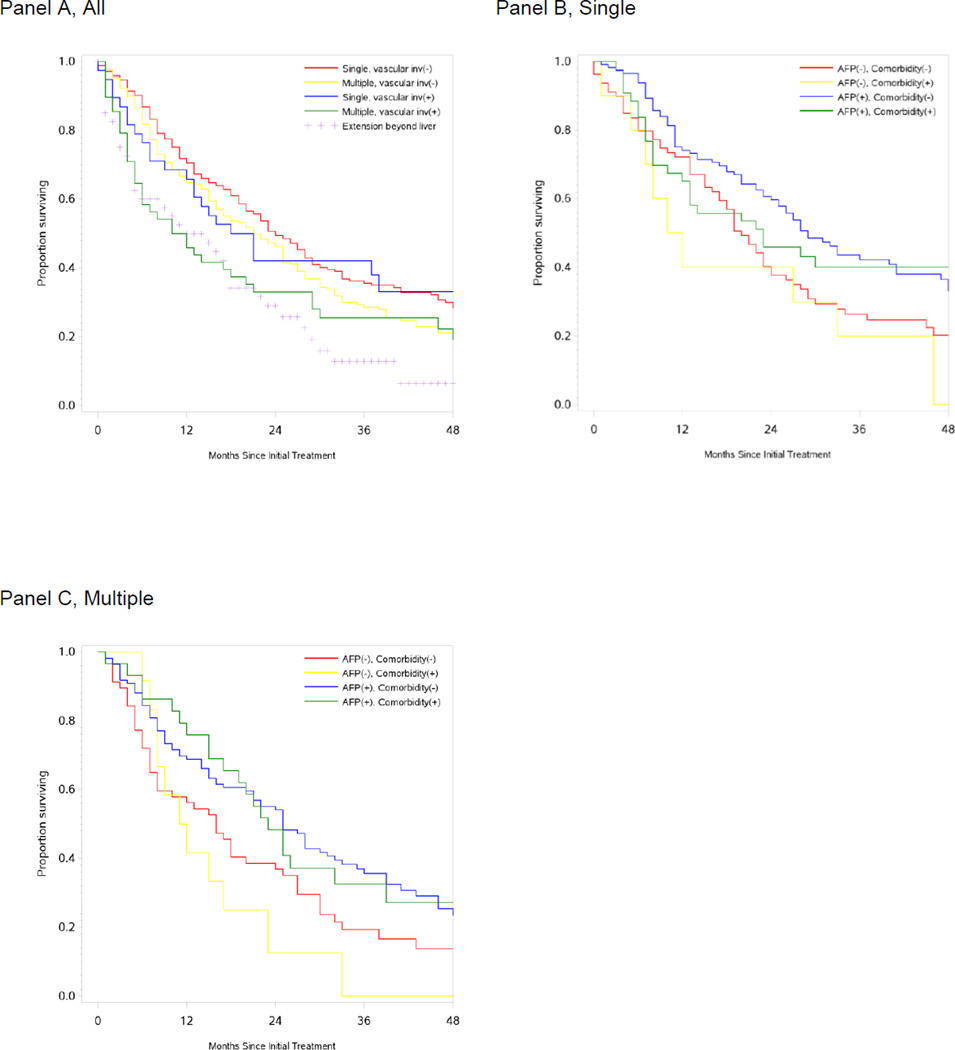

Median survival in TACE patients was 21 months (95% CI 18–23), ranging from 24 months (95% CI 21–28) in patients with solitary tumors without vascular invasion to 11 months (95% CI 5–20) in patients with multiple tumors and vascular invasion. Ninety day mortality was high in patients with extrahepatic spread (25%) or multiple tumors with vascular invasion (21%). Stratification by pre-diagnosis AFP screening and codes for liver comorbidity further refined these estimates (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Survival Estimates by Patient Subgroup Following Transarterial Chemoembolization

| Patient Subgroup | TACE with CHEMOTHERAPY GROUP Overall Survival Estimates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Extent | Liver Comorbidity |

AFP Screening |

N | Median Survival (months), 95% CI |

90 day n (%) |

24 month† n (%) |

|

Single, no vascular invasion |

All | All | 244 | 24 (21–28) | 231 (95%) | 112 (49%) |

| No | No | 79 | 20 (17–24) | 71 (90%) | 28 (38%) | |

| No | Yes | 112 | 29 (25–41) | 109 (97%) | 63 (60%) | |

| Yes | No | <11 | 11 (1–33) | <11 | <11 | |

| Yes | Yes | 43 | 23 (12-NA) | 42 (98%) | 17 (46%) | |

|

Multiple, no vascular invasion |

All | All | 207 | 21 (16–25) | 191 (92%) | 90 (46%) |

| No | No | 57 | 16 (8–24) | 51 (89%) | 21 (37%) | |

| No | Yes | 109 | 25 (20–31) | 100 (92%) | 55 (54%) | |

| Yes | No | 12 | 11.5 (7–23) | 12 (100%) | <11 | |

| Yes | Yes | 29 | 23 (15–39) | 28 (97%) | 13 (48%) | |

|

Singe, vascular invasion |

All | All | 38 | 19.5 (12– 38) | 33 (87%) | 14 (42%) |

|

Multiple, vascular invasion |

All | All | 48 | 11 (5– 20) | 38 (79%) | 14 (33%) |

|

Any^, vascular invasion |

No | No | 30 | 14.5 (12–29) | 25 (83%) | <11 |

| No | Yes | 44 | 19 (8–46) | 39 (89%) | 18 (45%) | |

| Yes | No | <11 | 3.5 (2–5) | <11 | 0 | |

| Yes | Yes | <11 | 5.5 (0–10) | <11 | <11 | |

|

Extrahepatic Extension or NOS |

All | All | 40 | 13.5 (5–18) | 30 (75%) | <11 |

22 patients were censored at 24 months. Cells with <11 patients suppressed to preserve confidentiality.

Because of small numbers, patients with single and multiple tumors with any vascular invasion were combined for analysis by AFP and liver comorbidity. Also because of small sample size, further subgroup analysis was not performed on patients with extrahepatic spread.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Survival Following Transarterial Chemoembolization. Survival estimates for patients with documented chemotherapy administration at time of TACE procedure for the entire cohort n=577 by tumor extent (A); and for single tumors without vascular invasion n=244 (B) and multiple tumors without vascular invasions n=207 (C) by AFP screening and liver comorbidity.

Patient sex, race/ethnicity, census tract median income, non-liver comorbidity, and cause of liver disease were not associated with survival (Table 1). Patients born in Asia or other non-US sites had significantly longer OS compared with US born patients—a possible surrogate for hepatitis B infection. Treatment at an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center and at a hospital with a solid organ transplant program was associated with significantly better OS.

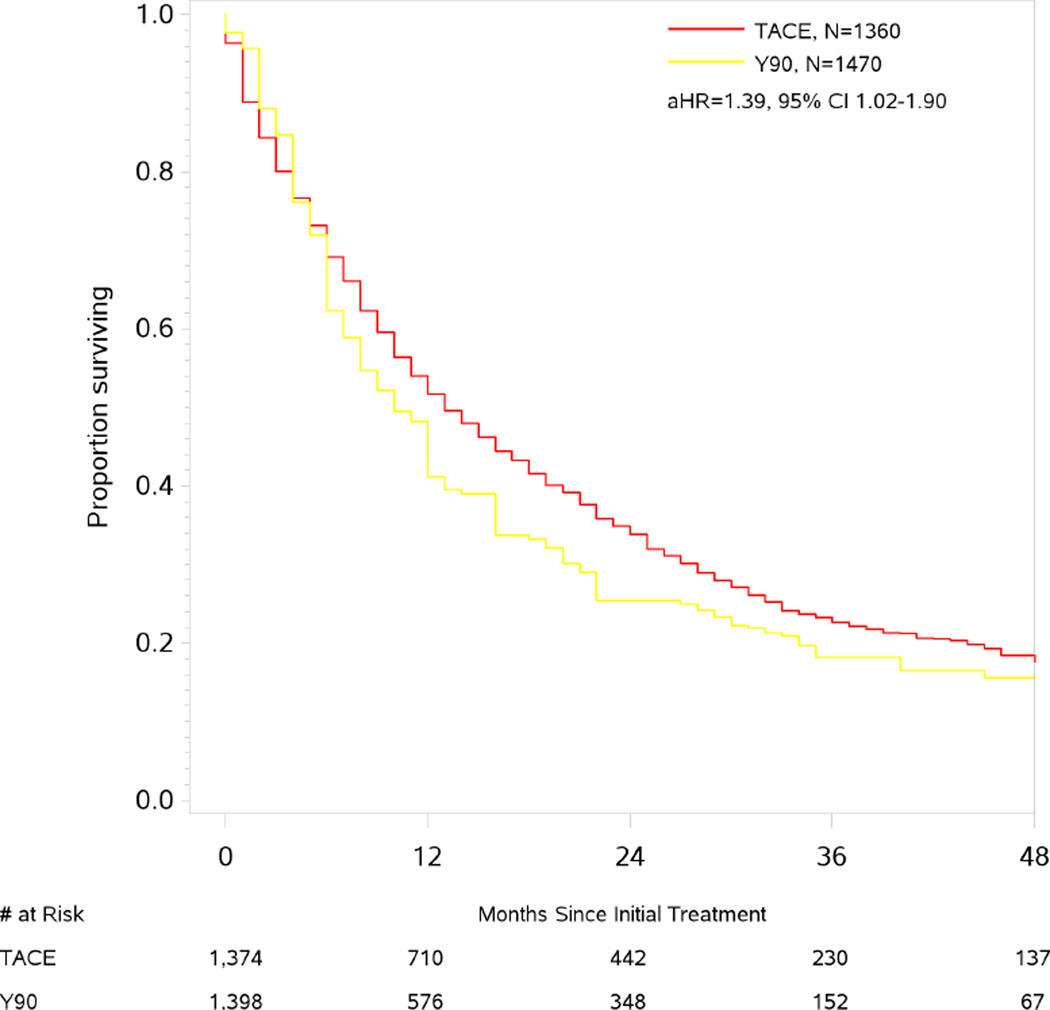

Comparative Effectiveness

Median survival in Y90 patients was 9 months (95% CI 1–41). In the PS-weighted population balanced across key clinical covariates (ETable 2), Y90 was associated with an increased risk of death compared with TAE/TACE, adjusted HR 1.39 (95% CI 1.02–1.90). The effect was more pronounced when restricting just to TACE patients, adjusted HR 1.88 (95% CI 1.40–2.53, ETable 3). We found little evidence that the greater risk of death with Y90 resulted from residual unmeasured confounding as trimming of patients treated contrary to prediction did not lead to an attenuation of the hazard ratio towards the null.

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort of patients with newly diagnosed HCC, the survival estimate of 21 months for the true chemoembolization patients suggest TACE effectiveness is retained across the broad range of health system settings where Medicare beneficiaries are treated in the United States; though treatment at a center with a solid organ transplant program or NCI Comprehensive status was associated with the best outcomes. However, we found that in the subgroup of TACE-treated patients whose disease was more extensive than is typically considered TACE amenable (extrahepatic disease or multifocal disease with macrocascular invasion), immediate post-treatment mortality was very high with 21 to 25% of patients dying within 90 days of treatment.

The expected duration of survival following TACE varies widely as it is dependent upon both the extent of cancer and the degree of underlying cirrhosis.[32–34] In well done[35] randomized clinical trials using conventional (non-bead) TACE for unresectable HCC, median OS has been reported between 13.8–28.7 months.[4, 5, 36] Better outcomes have been reported recently in patients with well compensated cirrhosis using the contemporary approach of doxorubicin-eluting bead TACE.[37–39] Based on the existing data, the Standards of Practice Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology has set the quality threshold of median survival following TACE at 20 months.[8] While we found the median survival among Medicare beneficiaries treated with initial TACE to meet this quality threshold, two prior population-based observational studies also using SEER-Medicare reported post-TACE median survivals of only <12 and 14 months.[9, 10] The first of these investigations was conducted in the 1990s when only 4% of patients were treated with TACE. As use and techniques of TACE have evolved since the 1990s, it is likely that survival has also improved over this time. The more recent investigation of HCC patients treated between 2000 and 2005 was designed to compare palliative approaches in the elderly; it intentionally excluded patients younger than 65 and those receiving subsequent curative therapies. In contrast we chose to retain younger patients eligible for Medicare on the basis of disability to more broadly investigate the effectiveness of TACE in the United States. We also retained patients who underwent subsequent curative surgery, transplant and ablative procedures as excluding such patients underestimates TACE effect by selectively excluding those with the best response. Because of these differences we do not believe these data to be conflicting, rather, our report expands on this prior work by providing survival estimates across a broader range of treatment scenarios.

Because registry data do not contain laboratory data or performance status, we could not evaluate outcomes by HCC-relevant clinical categories of Child Pugh or BCLC stage. To address this limitation we used surrogates for the components of BCLC stage (extent of cancer, performance status, and Child Pugh score)[40] to refine our survival estimates. We used the cancer-specific tumor extent from SEER that includes macrovascular invasion. However, the predominantly clinical staging paradigm of HCC differs greatly from other cancers. Concordance between registrar-reported vascular invasion has not been evaluated to the best of our knowledge, but may be poor. Codes for complications of cirrhosis prior to diagnosis were used as a marker of the extent of cirrhosis. As this approach relies on the thoroughness of physician coding, these codes likely underestimate the extent of cirrhosis and limit the direct clinical applicability of the estimates provided for patients with and without liver comorbidity in this analysis. Pre-diagnosis AFP screening was chosen given prior evidence of cancer screening as a marker of frailty,[41] though AFP is likely a marker for multiple factors associated with improved outcomes including possible earlier detection with a lower burden of disease and engagement with the healthcare system. While these means of stratifying patients is less granular than validated HCC staging systems, each component was strongly associated with survival.

Fifteen percent of TACE-patients in this cohort had disease beyond that for which TACE is currently recommended,[7] including multifocal disease with macrovascular invasion and extrahepatic disease. In this subgroup of patients with advanced cancer, 90 day mortality was very high, 21–25%. Because untreated patients are inherently different, we did not compare outcomes between treated and untreated patients to explore the extent to which this early mortality was the result of hepatic decompensation following treatment or ineffective treatment in terminally ill individuals. In this sicker group of patients it would be particularly relevant to know more detail about the technical aspects of TACE, specifically whether the procedure was performed using super selective techniques that minimize the damage to non-neoplastic liver, or whether a more extensive embolization was performed. Unfortunately this quality metric cannot be ascertained from embolization codes in any reliable fashion. However, if indeed patients with poorly compensated cirrhosis were treated with less selective embolization this might account for the poor outcomes of TACE in this advanced disease group. But, without this information we cannot definitively conclude whether it is all TACE that does not benefit patients with advanced disease, or merely poor quality TACE.

Patients with a poor performance status, diffuse infiltrative cancer, Child-Pugh C cirrhosis, and Child Pugh B cirrhosis with portal vein thrombosis all have an exceptionally poor prognosis even with TACE or Y90.[11, 32, 33] Unfortunately, there are few data available to help determine whether LRT improves outcomes in this high risk group, or if they are better served by sorafenib or supportive care. Studies designed to evaluate if TACE and/or Y90 improve outcomes over supportive care or sorafenib such as NCT01887717 (Y90 versus sorafenib in patients with portal vein occlusion) are difficult to complete, but of paramount importance.

Our exploration of the comparative effectiveness of Y90-radioembolization to TACE was limited by a small number of Y90 treated patients; however we found no suggestion that Y90 offered a survival advantage over TACE. The median survival of 9 months was well below what has been reported for patients with compensated cirrhosis following Y90-radioembolization,[11, 12, 15, 21, 32] and may simply reflect use of Y90 in patients with more advanced liver disease and a larger burden of cancer.

Our study also shows that while registry-linked claims data allow for a broad overview of outcomes of HCC treatment, the lack of HCC-relevant staging—specifically laboratory parameters and components of Child Pugh score—markedly limits the feasibility of a nuanced study. As HCC is one of a few cancers with a rising incidence and mortality in the US,[42] efforts should be made to incorporate laboratory parameters relevant to HCC staging into mandatory cancer registry reporting. Such efforts would improve the ability to study the comparative safety and effectiveness of emerging therapies for this deadly disease.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Survival by Treatment. Survival estimates for TACE and yttrium90-radioembolization are shown for the propensity score weighted population.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K07CA160722. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Financial Support: This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, K07CA160722, to Dr. Sanoff and the National Institute on Aging, R01AG023178, to Dr. Stürmer. Additional support was provided by the University Cancer Research Fund via the state of North Carolina to the Integrated Cancer Information and Surveillance System at UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

These data were presented in part at the 2014 ASCO meeting.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Sanoff receives research grants from Bayer and Novartis and has served as a consultant for Amgen. Dr. Stürmer receives salary support from the UNC Center of Excellence in Pharmacoepidemiology and unrestricted research grants from pharmaceutical companies (GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Sanofi-Aventis).

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ. Cronin KA SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2014. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/, based on November 2013 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davila JA, Morgan RO, Shaib Y, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Hepatitis C infection and the increasing incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1372–1380. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164–1171. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruix J, Sherman M. American Association for the Study of Liver D. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown DB, Nikolic B, Covey AM, Nutting CW, Saad WE, Salem R, et al. Quality improvement guidelines for transhepatic arterial chemoembolization, embolization, and chemotherapeutic infusion for hepatic malignancy. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2012;23:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Serag HB, Siegel AB, Davila JA, Shaib YH, Cayton-Woody M, McBride R, et al. Treatment and outcomes of treating of hepatocellular carcinoma among Medicare recipients in the United States: a population-based study. Journal of hepatology. 2006;44:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davila JA, Duan Z, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Utilization and outcomes of palliative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study in the United States. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2012;46:71–77. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318224d669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sangro B, Salem R, Kennedy A, Coldwell D, Wasan H. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a review of the evidence and treatment recommendations. American journal of clinical oncology. 2011;34:422–431. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181df0a50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sangro B, Carpanese L, Cianni R, Golfieri R, Gasparini D, Ezziddin S, et al. Survival after yttrium-90 resin microsphere radioembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma across Barcelona clinic liver cancer stages: a European evaluation. Hepatology. 2011;54:868–878. doi: 10.1002/hep.24451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulik LM, Carr BI, Mulcahy MF, Lewandowski RJ, Atassi B, Ryu RK, et al. Safety and efficacy of 90Y radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with and without portal vein thrombosis. Hepatology. 2008;47:71–81. doi: 10.1002/hep.21980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Riaz A, Ryu RK, Ibrahim S, et al. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using Yttrium-90 microspheres: a comprehensive report of long-term outcomes. Gastroenterology. 138:52–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilgard P, Hamami M, Fouly AE, Scherag A, Muller S, Ertle J, et al. Radioembolization with yttrium-90 glass microspheres in hepatocellular carcinoma: European experience on safety and long-term survival. Hepatology. 2010;52:1741–1749. doi: 10.1002/hep.23944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr BI, Kondragunta V, Buch SC, Branch RA. Therapeutic equivalence in survival for hepatic arterial chemoembolization and yttrium 90 microsphere treatments in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a two-cohort study. Cancer. 2010;116:1305–1314. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewandowski RJ, Kulik LM, Riaz A, Senthilnathan S, Mulcahy MF, Ryu RK, et al. A comparative analysis of transarterial downstaging for hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization versus radioembolization. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9:1920–1928. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lance C, McLennan G, Obuchowski N, Cheah G, Levitin A, Sands M, et al. Comparative analysis of the safety and efficacy of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and yttrium-90 radioembolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2011;22:1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kooby DA, Egnatashvili V, Srinivasan S, Chamsuddin A, Delman KA, Kauh J, et al. Comparison of yttrium-90 radioembolization and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2010;21:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno-Luna LE, Yang JD, Sanchez W, Paz-Fumagalli R, Harnois DM, Mettler TA, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Transarterial Radioembolization Versus Chemoembolization in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0481-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazzaferro V, Sposito C, Bhoori S, Romito R, Chiesa C, Morosi C, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for intermediate-advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase 2 study. Hepatology. 2013;57:1826–1837. doi: 10.1002/hep.26014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SEER-Medicare Linked Database; Applied Research, Cancer Control and Population Sciences. National Cancer Institute; 2014. [cited 2014 April 9]. Available from: http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/seermedicare/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Medical care. 2002;40 doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. IV-3-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulahannan SV, Duffy AG, McNeel TS, Kish JK, Dickie LA, Rahma OE, et al. Earlier presentation and application of curative treatments in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;60:1637–1644. doi: 10.1002/hep.27288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davila JA, Morgan RO, Richardson PA, Du XL, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Use of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2010;52:132–141. doi: 10.1002/hep.23615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson P, Henderson L, Davila JA, Kramer JR, Fitton CP, Chen GJ, et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: development and validation of an algorithm to classify tests in administrative and laboratory data. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2010;55:3241–3251. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1387-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faurot KR, Jonsson Funk M, Pate V, Brookhart MA, Patrick A, Hanson LC, et al. Using claims data to predict dependency in activities of daily living as a proxy for frailty. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2015;24:59–66. doi: 10.1002/pds.3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren JL, Harlan LC, Fahey A, Virnig BA, Freeman JL, Klabunde CN, et al. Utility of the SEER-Medicare data to identify chemotherapy use. Medical care. 2002;40 doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020944.17670.D7. IV-55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sturmer T, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ. Insights into different results from different causal contrasts in the presence of effect-measure modification. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2006;15:698–709. doi: 10.1002/pds.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sturmer T, Rothman KJ, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Treatment effects in the presence of unmeasured confounding: dealing with observations in the tails of the propensity score distribution--a simulation study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:843–854. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Riaz A, Ryu RK, Ibrahim S, et al. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using Yttrium-90 microspheres: a comprehensive report of long-term outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:52–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Kulik LM, Riaz A, Ryu RK, Baker TB, et al. Chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: comprehensive imaging and survival analysis in a 172-patient cohort. Radiology. 2010;255:955–965. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raoul JL, Sangro B, Forner A, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, Bolondi L, et al. Evolving strategies for the management of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: available evidence and expert opinion on the use of transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer treatment reviews. 2011;37:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose SC, Kikolski SG, Gish RG, Kono Y, Loomba R, Hemming AW, et al. Society of Interventional Radiology critique and commentary on the Cochrane report on transarterial chemoembolization. Hepatology. 2013;57:1675–1676. doi: 10.1002/hep.26000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doffoel M, Bonnetain F, Bouche O, Vetter D, Abergel A, Fratte S, et al. Multicentre randomised phase III trial comparing Tamoxifen alone or with Transarterial Lipiodol Chemoembolisation for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients (Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive 9402) European journal of cancer. 2008;44:528–538. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varela M, Real MI, Burrel M, Forner A, Sala M, Brunet M, et al. Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: efficacy and doxorubicin pharmacokinetics. Journal of hepatology. 2007;46:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhanasekaran R, Kooby DA, Staley CA, Kauh JS, Khanna V, Kim HS. Comparison of conventional transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and chemoembolization with doxorubicin drug eluting beads (DEB) for unresectable hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC) Journal of surgical oncology. 2010;101:476–480. doi: 10.1002/jso.21522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin RC, 2nd, Rustein L, Perez Enguix D, Palmero J, Carvalheiro V, Urbano J, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of doxorubicin-loaded microsphere for treatment of hepatocellular cancer: a multi-institutional registry. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2011;213:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Seminars in liver disease. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faurot KR, Jonsson Funk M, Pate V, Brookhart MA, Patrick A, Hanson LC, et al. Using claims data to predict dependency in activities of daily living as a proxy for frailty. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2014 doi: 10.1002/pds.3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, Eheman C, Zauber AG, Anderson RN, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116:544–573. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.