Abstract

This paper examines the activities of churches in Baltimore, Maryland, concerning the issues of sexuality, whether they potentially stigmatize persons with or at risk for HIV/AIDS, and to what extent individual agency versus institutional forces influence churches in this regard. In-depth interviews were conducted with 20 leaders from 16 churches and analyzed using a grounded theory methodology. Although many churches were involved in HIV/AIDS-related activities, the content of such initiatives was sometimes limited due to organizational constraints. Church leaders varied, however, in the extent to which they responded in accordance with or resisted these constraints, highlighting the importance of individual agency influencing churches’ responses to HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Stigma, Faith-based

Introduction

In the United States, an estimated 551,932 persons are living with HIV/AIDS (CDC 2009). HIV-related stigma, defined as “the prejudice, discounting, discrediting, and discrimination directed at people perceived to have HIV/AIDS and the individuals, groups, and communities with which they are associated,” is one of the greatest obstacles to HIV prevention, treatment, and care (Herek 1999, p. 1107; Herek et al. 2002; Mahajan et al. 2008). Breaking through such stigma is essential to effectively address the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Piot 2006).

Conceptualizations of stigma have traditionally focused on the perceptions of individuals and the consequences of such perceptions on their interactions with others (Goffman 1963; Jones et al. 1984; Crocker et al. 1998). Following Goffman (1963), stigma is typically defined as an undesirable attribute that sets a person apart from others and associates the labeled person to negative evaluations or stereotypes. In response, interventions to address HIV-related stigma commonly employ strategies to increase empathy and altruism toward or reduce anxiety and fear of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) (Brown et al. 2003; Klein et al. 2002; Mahajan et al. 2008).

Although stigma arises through an interpersonal process, it occurs in specific socio-cultural contexts. In recent years, researchers have expanded their conceptions of stigma to include the structural features—the physical, social, cultural, political, economic, legal, and/or policy aspects—of those environments that facilitate and maintain its existence (Link and Phelan 2001; Parker and Aggleton 2003; Sumartojo 2000). For example, individuals’ perceptions about HIV may be heavily influenced by the actions of community institutions including schools, government agencies, health care facilities, and places of worship, among others. Achieving sustainable reductions in HIV-related stigma requires a better understanding of how institutions shape public attitudes toward HIV/AIDS and perpetuate biases against the social groups most seriously affected by the epidemic (Blankenship et al. 2000; Cohen and Scribner 2000).

Religious organizations represent an important socializing force in the United States and may therefore be an ideal venue in which to address the stigma associated with health conditions such as HIV/AIDS. At least 81% of Americans identify with an established religious denomination or group, and 45% report attending church at least once weekly (Kosmin et al. 2001). Churches, in particular, exist in virtually all communities and are often valued as trusted sources of information and guidance (Baldwin et al. 2008; Fullilove and Fullilove 1999; Taylor et al. 2004). In many cases, churches’ actions have been a catalyst for positive social changes (e.g., abolition, civil rights) (Lincoln and Mamiya 1990; Boyd-Franklin 2003).

Churches deliver a wide range of services to their congregants and surrounding communities including direct delivery of counseling, transportation, and other services as well as information related to employment, housing, finances, and health care (Taylor et al. 2004; Boyd-Franklin 2003). Using data from the Black Church Family Project, Thomas et al. (1994) found that 67% of churches surveyed had at least one community outreach program, 54% operated two or more programs, and nearly 41% sponsored three or more programs (Thomas et al. 1994). While churches are clearly important social service providers, many churches have at times operated in ways that have stigmatized a variety of conditions either through their overt condemnation of groups or behaviors or through non-action (Ayers 1995; Coyne-Beasley and Schoenbach 2000; Fullilove and Fullilove 1999; Merz 1997). For example, many churches’ initial response to HIV was to attribute it to homosexuality and social decay (Merz 1997). Early in the epidemic, categorizations of “respectable” community members versus marginal population groups (e.g., injection drug users, men who have sex with men) paralyzed mobilization efforts to address this issue (Cohen 1999). Over the last two decades, many churches have begun providing a variety of HIV/AIDS-related services. At the same time, however, moral codes and beliefs about sin have limited some churches’ involvement in HIV prevention and care (Ayers 1995; Coyne-Beasley and Schoenbach 2000; Fullilove and Fullilove 1999).

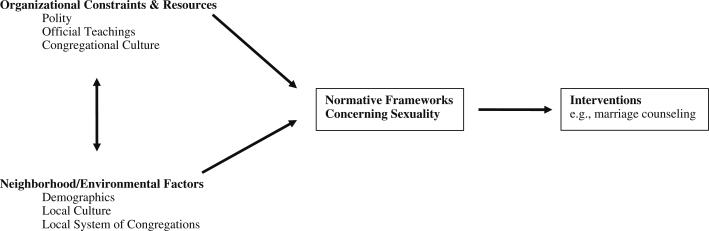

Religious doctrine and church actions are not, however, always consistent. Rather, churches’ programs, practices, and policies regarding sexuality are the result of many interacting forces (Ellingson et al. 2001). Drawing on case studies of churches in three different neighborhoods in Chicago, Ellingson et al. (2001) illustrated how features of the organization (such as polity, congregational culture, and officials teachings) as well as local context (such as demographic composition or the sexual culture of a neighborhood population) influence how religious organizations address sexuality (Fig. 1). Polity types or forms of church governance, for example, range from hierarchical and centralized to relatively democratic and decentralized (Ellingson et al. 2001). Theological orientations that have more hierarchical and centralized polities, such as Roman Catholicism and many mainline Protestant denominations1 have official teachings on sexuality, deviations from which may have negative consequences. Churches within conservative fundamentalist and evangelical traditions2 especially tend to adhere to a general set of guidelines concerning sexual issues based upon a literal interpretation of the Bible (Ellingson et al. 2001; Taylor et al. 2004). Churches that belong to relatively conservative denominations may, however, opt for a more flexible approach to sexual issues depending on the needs or desires of their membership or surrounding communities. According to the model in Fig. 1, church leaders negotiate among various structural factors (i.e., institutional and local considerations) to develop their understandings of and attitudes toward sexuality. In turn, these understandings and attitudes determine how they identify the causes of sex-related problems facing their congregations and formulate or justify their responses to sexual issues. In other words, church leaders are seen to be acting within a context that gives meaning to their actions but may also constrain them.

Fig. 1.

A model of constraints on congregational responses to sexuality (Ellingson et al. 2001). Copyright: Hunt SA, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography p. 10, copyright 2001 by Sage Publications, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Sage Publications, Inc.

Despite such constraints, examples abound of individual church variation in response to sexual issues. For instance, both the Episcopal dioceses of New Hampshire and California made headlines when, in the face of great resistance from the broader Episcopal Church and the worldwide Anglican Communion to which they belong, they openly elected gay men as Bishops (Banerjee 2006; Goodstein 2003). Likewise, besides promoting abstinence, some churches distribute condoms, regardless of institutional doctrine (Coyne-Beasley and Schoenbach 2000; Tesoriero et al. 2000). Senior clergy are pivotal in shaping their church's mission and interpreting and applying church doctrine to particular issues (Taylor et al. 2004). To our knowledge, however, no studies have examined the role of structural features of churches versus the individual agency of their leaders in shaping churches’ responses to HIV/AIDS.

Building on the Chicago study, we conducted an in-depth examination of the programs, practices, and policies of churches in Baltimore City, Maryland, with regard to issues of human sexuality and, in particular, HIV/AIDS. Of specific interest was the extent to which these churches provided support for or potentially contributed to the stigmatization of persons living with or at risk for HIV/AIDS and the extent to which individual agency versus institutional forces influenced churches’ actions in this regard.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in Baltimore City, Maryland, between February and November 2005. As of December 31, 2004, there were a total of 14,346 persons living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA) in Baltimore corresponding to a rate of 2,203 cases per 100,000 people (AIDS Administration 2005).

According to the 2000 Religious Congregations and Membership Study, Baltimore City has 410 congregations with a total of 254,661 adherents3 (ARDA 2000). The data exclude, however, most of the historically African American denominations as well as some other major groups. Adjusting for these missing denominations and other religious groups, the total number of adherents is estimated to be 530,498 (ARDA 2000).

Sampling Strategy and Ethics Approval

Selection of participants was based on a maximum variation sampling scheme in which we attempted to capture a diversity of beliefs and actions regarding sexuality and HIV/AIDS (Patton 2001). The pool of churches from which the sample was recruited was identified through the phone book, Internet, driving tours of the city, and recommendations of local community agencies. Eligibility requirements stipulated that interviewees be ≥18 years of age, English-speaking, and hold a leadership position with a church located in Baltimore. Eligible persons were first contacted by a letter that described the study and requested their participation. Follow-up phone calls and visits were made to those who did not respond within 2 weeks. Twenty-eight church leaders were invited to participate, of whom 20 (71%) were interviewed. Two of those (25%) who did not participate declined due to time constraints and lack of interest in the project. The remainder neither responded to the invitation letter nor could be reached by phone, email, or in-person visits during the study period. All participants provided informed written consent and agreed to be interviewed without financial or other incentive. Ethics approval was granted by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Internal Review Board.

Data Collection

Participants were interviewed by one of two masters-level research investigators trained in qualitative research methods. Interviews took place at a location of the participants’ choice, most often their home or office, and lasted 60–90 min. A field guide, containing a core set of open-ended questions, was used to facilitate discussion. Topics covered included inquiries into churches’ internal and outreach activities, HIV/AIDS-specific prevention and care activities, and theological views relating to sexuality. Interviewers were encouraged to probe for additional details as necessary and further explore relevant themes as they emerged.

Analyses

All in-depth interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim into text. These data were analyzed using a grounded theory methodology involving an inductive approach to identify emergent themes and relations between themes (Glaser and Strauss 1967). As such, transcripts were read several times in their entirety. Based on these readings, along with a comprehensive literature review, a list of codes for domains of interest was developed. Textual data were then coded using Atlas.ti© (version 4.1, Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) and examined for patterns and variability among responses. As data collection progressed, findings were shared back with a subset of participants for affirmation, contradiction, clarification, and elaboration. This process took place by phone and entailed asking participants to comment on emerging themes.

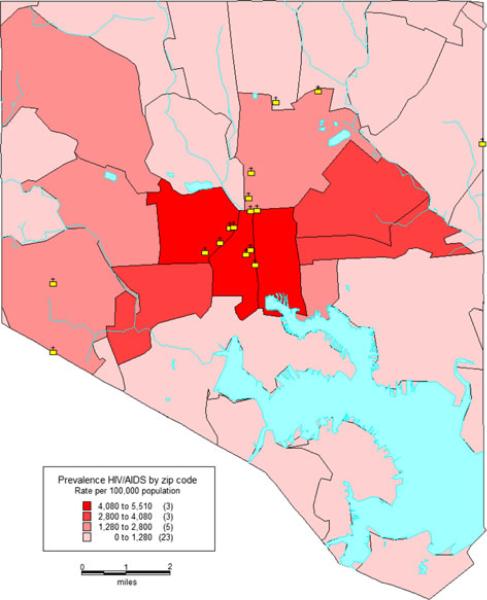

Geographic Information System (GIS) software (MapInfo Professional v9.0, MapInfo Corporation, Troy, NY) was used to examine the distribution of churches from which representatives were interviewed and HIV/AIDS prevalence rates per 100,000 persons by zip code. The number of HIV/AIDS cases per Baltimore City zip code was obtained from the Maryland AIDS Administration (AIDS Administration 2005). Population denominators used to calculate prevalence rates were from the 2000 US Census.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Participants and Churches with Which They were Affiliated

The final sample of participants included 20 senior clergy and lay leaders from 16 churches. Participants represented a variety of Christian traditions including: African Methodist Episcopal (1), Baptist (2), Catholic (2), Episcopalian (1), Lutheran (1), Methodist (2), Presbyterian (2), Southern Baptist (1), Unitarian (1), and no denominational affiliation (3). Half of those interviewed were female. Churches with which participants were affiliated were spread throughout the city. Half were located in zip codes in the top quartile of HIV/AIDS prevalence rates (AIDS Administration 2005). Table 1 summarizes additional demographic characteristics of the 16 churches from Baltimore City with which participants were affiliated. Figure 2 shows the distribution of churches with which participants were affiliated overlaid on HIV/AIDS prevalence rates by zip code. Half were located in zip codes in the top quartile of HIV/AIDS prevalence rates.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participating churches in Baltimore, Maryland (N = 16)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Denomination | |

| Catholic | 2 (13) |

| Mainline protestant | 9 (56) |

| Evangelical protestant | 3 (19) |

| Other | 2 (13) |

| No. of members | |

| Small <200 | 3 (19) |

| Medium 201–500 | 9 (56) |

| Large >500 | 4 (25) |

| Racial compositiona | |

| Majority black | 8 (50) |

| Majority white | 8 (50) |

| Church age | |

| Young 1–50 years | 3 (19) |

| Mid-age 51–100 years | 3 (19) |

| Old > 100 years | 10 (63) |

Greater than 75% black or white parishioners

Fig. 2.

Distribution of churches with which participants were associated overlaid on prevalence HIV/AIDS by zip code

Church Involvement in HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care

Table 2 summarizes the HIV-related programs, practices, and policies of the Baltimore City churches with which participants were affiliated. Although only four had established HIV/AIDS-specific ministries, church involvement in HIV/AIDS prevention and care activities was widespread. In particular, 12 of the 16 were engaged in efforts to raise awareness and educate their congregations about HIV and its transmission, five had offered HIV testing on church premises at least once during the past year, three facilitated HIV/AIDS support groups, and one provided case management services for PLWHA. Although most churches had programs, practices, and policies that demonstrated support for and provided services to persons living with and at risk for HIV/AIDS, these were not necessarily mutually exclusive of other potentially stigmatizing attitudes and actions, particularly with regard to sexual activity. For example, participants reported that only half of the churches with which they were affiliated facilitate a forum for discussion of sexuality that includes candid information about methods of risk reduction such as condoms, whereas the other half either reported relying solely on prevention messages of abstinence outside the context of marriage or simply avoid the issue of sex altogether.

Table 2.

Participating Baltimore churches’ HIV-related programs, practices, and policies (N = 16)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Has established HIV/AIDS ministry | |

| No | 12 (75) |

| Yesa | 4 (25) |

| Provides HIV/AIDS education and awareness | |

| No | 4 (25) |

| Yes | 12 (75) |

| Provides HIV testing on-site during the previous year | |

| No | 11 (69) |

| Yes | 5 (31) |

| Holds HIV/AIDS support groups | |

| No | 13 (81) |

| Yes | 3 (19) |

| Provides case management for PLWHAb | |

| No | 15 (94) |

| Yes | 1 (6) |

| Church leader(s) attended a training on HIV/AIDS | |

| No | 7 (44) |

| Yes | 9 (56) |

| Church leader(s) are active in local HIV/AIDS coalition | |

| No | 13 (81) |

| Yes | 3 (19) |

| Facilitates candid discussion of risk reduction | |

| No | 8 (50) |

| Yes | 8 (50) |

| Affirms persons of all sexual orientationsc | |

| No | 8 (50) |

| Yes | 8 (50) |

| Facilitates candid discussion of risk reduction and affirms persons of all sexual orientations | |

| No | 12 (75) |

| Yes | 4 (25) |

| Formed local partnerships to conduct formal needs assessment of congregations' issues | |

| No | 14 (88) |

| Yes | 2 (12) |

All of the HIV/AIDS ministries were in churches with majority Black congregations. Two were in zip codes in the highest quartile for prevalence of HIV/ AIDS

Persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA)

These churches represent themselves as welcoming Christian churches (i.e., “gay friendly”). This does not imply that they are allowed to ordain gay ministers, perform holy unions, etc., as these issues are usually set at the denominational level and therefore outside of the auspices of individual churches. For the purpose of this study, affirmation means that the congregation welcomes and treats gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) persons with love and respect and does not consider homosexuality to be a sin

Organizational and Contextual Barriers to and Facilitators of Churches’ Responses to HIV/AIDS

Consistent with the Chicago model, environmental–structural factors such as the neighborhood context within which participating churches were located and the organizational features of the churches themselves were found to influence church leaders’ normative frameworks concerning sexuality and, subsequently, the extent and nature of their churches’ involvement in HIV/AIDS prevention and care initiatives. Neighborhood demographic characteristics, for example, played an especially important role as the impetus for taking action related to HIV/AIDS. As one participant conveyed,

The messages that are coming out are that it [HIV/AIDS] is disproportionately affecting African Americans. So, for black congregations now, if the pastor or the minister is aware of larger economic and social issues in his community, he can't avoid talking about HIV/AIDS. It's almost irresponsible (Episcopalian).

Another participant reinforced this notion that neighborhood demographics influence church action.

As the pastor of a progressive church in a neighborhood that is essentially a gay neighborhood, I don't know how HIV disease could not be a part of the ministry...We have to do what we do because of where we're located (Presbyterian).

Congregational culture and mission were also essential determinants of the types of activities that took place based on church leaders’ reports. For example, while all of the participants agreed that there is a theological basis for providing care and compassion to persons infected and affected by HIV/AIDS, prevention activities, such as sex education and HIV testing, were predominantly considered to be secular social services. Thus, churches that identify more as communities of worship versus agents of social action may be less likely to provide such services to their congregations. As one pastor explained,

We're not really an activist congregation and we can't offer a lot of programs...We don't have, at this point, any particular programs dealing with AIDS or support groups or anything like that although it's not something that we've tried to hide or anything (Lutheran).

In expressing her desire for religious institutions to provide more social services, a participant who founded a small women's health ministry at her church provided the following analogy:

What I'd like to see more of is meeting people's practical needs, having...Like for divorced people, for single mothers, to help people that are poor or sick or with AIDS or for people that just need help in general, just really practical ministry. Some churches are better at that than others...you know the story of Mary and Martha, the Bible story where Jesus comes to visit?...Well, Mary and Martha are sisters. And when Jesus came to their house, Martha was busy fixing food and all that stuff. And Mary sat at Jesus’ feet, worshipping Him, just crying and washing His feet with her hair. And so Martha got frustrated and was like, “Jesus, don't you see my sister's not doing anything? Tell her to help me.” And He said, “Martha, Martha, you are troubled about many things, but you have need of this part [too].” This worship...So my theory is, there are Martha churches, and there are Mary churches. There are worshipping churches, and then there are working practical churches, which we need both because you need to have the practical, and you need to have the worship. Even though we do have some outreach, my church is a Mary church. We worship more than have the practical ministry. Others have more of the practical ministries, but you could not raise your hand in the air [to worship]...I'd like to see churches blend more Mary and Martha (Non-denominational).

Similarly, the pastor of yet another church describes how he strives to achieve this balance.

Some churches you come to they're all spiritual, “God, Jesus, Hallelujah, thank you God. Let's worship and we go home.” Then there are the churches that are all social. It's all about the revolution. It's all about hitting the street. What we try to do here is be spiritually sensitive but socially relevant... So I talk from the pulpit about issues that happen on a national level and international level and I have tried to push and promote, in general, good health whether its diet and exercise, AIDS, STDs (Baptist).

Official church teachings concerning sex and sexuality were also of consequence in terms of HIV-related actions, although more so in terms of the content and quality of HIV/AIDS activities as opposed to whether such activities took place. For example, when asked what her pastor specifically says about HIV/AIDS in his sermons, one woman who is the president of her church's HIV/AIDS ministry explained

He's real open. One of the most open and straightforward to the crux of the problem pastors that I know of in Baltimore... “You going out here. You're going against God's word, and you end up with AIDS.” Homosexuality, just having sex period, not married and all that, you know...it's all within the context of the Bible (African Methodist Episcopal).

In most cases, existing canons of belief and practice did not result in public messages of moral judgement but did sometimes limit the scope of prevention activities such as sex education. The following excerpt exemplifies a common sentiment.

The way I feel, as a pastor, is that the Bible says that there should be a husband and a wife and the two of them are to multiply and replenish the earth. So, if you show me two of the same sex replenishing the earth, then maybe I could go along with what you are talking about [discussions of relationships and sexual behaviour between persons of the same sex]. But until that happens, I cannot (Baptist).

On the other hand, churches that were described as being affirming of persons of all sexual orientations were not necessarily engaged in more comprehensive, or in some cases, in any sex education at all. According to one pastor,

Although we welcome gay men and women into the church, a lot of people are not comfortable talking about sexuality, period. I had one person say to me, “Well, I don't want to know what two men do in bed together.” And I said to her, “Well, trust me. They probably don't want to know what you and your husband do in bed together either.” So this idea of being comfortable and talking about who we are, it is a real growing process...At least we're talking. The church, period—and I don't care what denomination—has a difficult time talking about people as sexual beings (Lutheran).

Individual Agency Among Church Leaders and Churches’ Responses to HIV/AIDS

While church leaders’ normative frameworks concerning sexuality often stem from official teachings sanctioned by the governing bodies of their respective denominations, within this sample, there was great diversity in how churches addressed sexual issues both within and across denominations. As one pastor explained

The labels don't mean much anymore. The same conservative, liberal struggle is in every denomination. It's in every congregation. That's why my joke is: “Don't say you go to a Presbyterian Church. Tell me which Presbyterian Church and then I can tell you what theology's being preached there.” And that's true. It all depends on the parish and who the pastor is and who the people are and what they've chosen to be the significant points of emphasis that they want to make (Presbyterian).

With regard to HIV/AIDS initiatives in particular, several church leaders described a complex negotiation process they underwent as they attempted to reconcile official teachings concerning sex and sexuality with prevention activities they deemed necessary. In the words of one pastor,

We're supposed to teach abstinence and that is something that we do. But reality shows that not everyone is going to be abstinent. We did a needs assessment and we're finding that kids are dying and adults are dying and even seniors are dying from HIV and AIDS so there needs to be some kind of education...We believe if you follow God's word and if you live according to His principles, then you won't have to deal with these issues. But if, in fact, you do as you and I and everyone else in the world does, if we do sin, if we do slip, then you need to know what to do in order to save your life because it becomes a life or death issue... Our first and foremost teaching is always on abstinence. We want to make sure that if you're not married then you're not having sex with someone. Just basic Bible doctrine that we're sticking to and we're not diminishing that at all. But the reality still exists that persons who may do wrong need to know what to do...We're all striving to live a life for Christ and we promote that. But, we also have to live in the reality of the times that are ours...it is time for us, as a church, to speak out and educate our community, the church community as well as our outside community (Southern Baptist).

Others were more blatant in their dissent of existing denominational policies concerning sex and sexuality. In the following excerpt, one such pastor defends his decision to not just talk about but also distribute condoms to persons who are sexually active.

I'm in the inner city. So, I've got to deal with the rugged realities of what I'm faced...These girls are having babies, and they ain't stopping. So, at least let me try to slow it down. Even if we don't stop it 100 percent, let's slow it down with condoms. Maybe they'll use them or they'll tell the boy to put it on. And so in these workshops we hand out condoms...I have different people I'm ministering to. And if I'm just ministering in one way, I miss this whole crowd over here. And so you have to able to be open and not say, “I'm going to lose this person if I don't help them.” And if the way to help them is to give them some condoms, then I'll take the criticism (Baptist).

This particular participant also relayed, however, that unlike more hierarchical denominations, he felt that his governing body had less sway over what types of activities actually took place at the local level. Furthermore, he felt that much of his success in being able to address sexual health issues stemmed from his having been well known and respected by both his church and the surrounding community for a long time.

Discussion

Our findings are consistent with other studies that have shown that most religious leaders consider HIV/AIDS to be an important public health issue facing members of their congregations and recognize the need for HIV/AIDS prevention and support services to be provided (Coyne-Beasley and Schoenbach 2000; Tesoriero et al. 2000; Tyrell et al. 2008). Our results also indicate, however, that despite widespread involvement in such efforts, some churches may still inadvertently contribute to the stigmatization of persons living with or at risk for HIV/AIDS by virtue of whether and how issues related to human sexuality are addressed. For example, by espousing religious doctrine that attributes notions of responsibility and controllability to PLWHA for their illness, some churches potentially undermine other messages of care and compassion that they may be trying to promote and further marginalize those whom they are trying to help. In describing the Black community's response to HIV in the late 1990s, Cohen notes that even when they started AIDS ministries, many clergy still preached against what they believed to be the “sinful” behavior involved in the transmission of HIV (Cohen 1999). Such attitudes and behavior appear to be far less prevalent among representatives of the churches sampled for this inquiry compared to those of previous studies conducted in other settings (Genrich and Brathwaite 2005; Nyblade et al. 2003). Many participants did, however, express a reluctance to address sexual behavior beyond promoting abstinence outside the context of marriage or opposition to homosexuality. This reluctance limited the scope of their churches’ HIV/AIDS prevention activities as well as possibly deterred some people from taking advantage of other available services due to how they had become infected.

Our data also support findings from the Chicago study that multiple organizational and environmental–structural factors may influence church leaders’ normative frameworks concerning sexuality and subsequent actions to address sexual health issues, such as HIV/AIDS, including characteristics of the local population (both members of the congregation and those living in the surrounding community), congregational culture in terms of the organization's mission, and doctrines that prescribe specific norms of sexual behavior. The data also reveal, however, that, with regard to providing a framework for understanding the extent and nature of a religious organization's involvement in HIV prevention activities in particular, the Chicago model (Fig. 1) is incomplete. What appears to be lacking from the model based on findings from this study is a level of individual agency that explains why some church leaders strictly adhere, others subtly dissent, and still others openly deviate from existing conventions on sex and sexuality, particularly those based on religious doctrine. The insertion of such agency into the model (see Fig. 3) creates new possibilities for HIV/AIDS intervention options as conceived by both church leaders and their congregation members, and in turn the reduction of HIV-related vulnerability.

Fig. 3.

Revised model of constraints on congregational responses to sexuality. Modifications are found in numbers 3, 5, & 6

Drawing on Giddens's theory of structuration (1976), structure and agency are a duality that cannot be conceived apart from one another. In his words, “social structures are both constituted by human agency, and yet, at the same time, are the very medium of this constitution” (Giddens 1976, 121). In this regard, church leaders’ actions concerning sexual health issues, such as HIV/AIDS, are shaped by the structures of which they are a part, but it is also only through their individual or collective actions that these structures are altered or maintained. While institutions such as churches may promote certain moral codes and have established ways of doing things concerning sex and sexuality that may have negative implications for HIV prevention and care, these can be changed when people start to ignore, replace, or reproduce them differently. Thus, in seeking to promote church leaders’ involvement in various HIV/AIDS initiatives, one must not only be aware of the ideological, cultural, and demographic features of a given church and its surrounding community, but, when any of these act as constraints for positive action, also identify potential motivating and enabling factors for persons who might challenge these structures.

Religious representatives who were interviewed for this study and whose churches’ HIV prevention activities conflicted on any level with official teachings concerning sex and sexuality most often cited their knowledge about HIV/AIDS and awareness of how it impacts their communities as justifications for their actions. Having attended trainings on HIV/AIDS or conducted a formal needs assessment of their congregations and communities appears to have been particularly influential in this regard. Similarly, a nationwide survey of the attitudes of African American Baptist ministers revealed that those who had previous HIV training were more likely than those who had not received training to have delivered sermons that concerned and detailed specific information about HIV and to sponsor HIV/AIDS workshops at their churches for members of their congregations (Crawford et al. 1992). Consistent with a qualitative study of clergy from Trinidad, church leaders’ personal experiences with PLWHA also appear to be positively associated with current involvement in more comprehensive approaches to sex education and other forms of HIV/AIDS prevention (Genrich and Brathwaite 2005). Church leaders’ length of tenure with a particular religious organization and reputation within the community may facilitate their ability to engage in more controversial initiatives. Likewise, the support and ongoing commitment of members of the congregation is essential to sustain such activities and to ensure that the message of acceptance and service is consistently communicated to the broader public.

This study was limited by its small sample size and single geographic location, thus the findings may not be generalizable to other populations and settings. The small sample size also precluded our ability to make generalizations based on churches’ racial composition or other demographic characteristics. Others have found that churches that have existed longer, have larger congregations, have a majority of members from the middle class, own their own building, have more paid clergy and other staff, and are led by ministers with more years of formal education are most likely to offer community outreach programs (Rubin and Billingsley 1994; Thomas et al. 1994). Lastly, the results are based on the self-reports of church leadership who self-selected to participate in the study and thus are subject to potential bias. Nonetheless, this study provides greater insight into how church programs, practices, and policies regarding sexual health issues, such as HIV/AIDS, are a product of both the agency of church leaders and the organizational and environmental contexts in which they operate.

Public health professionals and religious organizations have developed successful collaborations to address a variety of health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and breast cancer (Campbell et al. 2007). Similar efforts have also begun to emerge for HIV prevention programing (Francis and Liverpool 2008). Public health professionals wishing to engage churches in these efforts must recognize that not all churches, or even all those within a given denomination, will be the same with respect to the topics they are willing to cover and activities they are willing to conduct with their congregations. Rather, church responses to sexual health issues, such as HIV, are often a matter of negotiation at multiple levels. In particular, church leaders must often reconcile the tensions that may exist, for example, between their belief in and desire to adhere to official teachings concerning sex and sexuality and their commitment to serve the needs of individuals within their congregations and community settings. As such, it would behoove public health practitioners to meet with and get to know local church leaders so as to better understand the motivations for churches’ actions and to identify the best means by which to tap the collective powers of these individuals to improve the overall quality of faith-based HIV/AIDS initiatives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant #: R01 AI49530).

Footnotes

Examples of mainline Protestant denominations include: American Baptist Churches in the USA, Episcopal Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Presbyterian Church (USA), United Church of Christ, and United Methodist.

Examples of evangelical denominations include: Assemblies of God, Independent Baptists, Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, Church of Christ, Pentecostal, Presbyterian Church in America, and Southern Baptists.

Congregational “adherents” include all full members, their children, and others who regularly attend services.

Contributor Information

Shayna D. Cunningham, Sociometrics Corporation, Los Altos, CA, USA 170 State Street, Suite 260, Los Altos, CA 94022, USA.

Deanna L. Kerrigan, Department of International Health, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA 170 State Street, Suite 260, Los Altos, CA 94022, USA.

Clea A. McNeely, Department Population, Family, and Reproductive Health, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

Jonathan M. Ellen, Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

References

- AIDS Administration . The Maryland 2005 HIV/AIDS annual report. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Baltimore, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Data Religion Archives (ARDA) [February 7, 2007];Baltimore County, Maryland membership report, 2000. 2000 from http://www.thearda.com/mapsReports/reports/counties/24510_2000.asp.

- Ayers JR. The quagmire of HIV/AIDS related issues which haunt the church. The Journal of Pastoral Care. 1995;49(2):201–210. doi: 10.1177/002234099504900209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JA, Daley E, Brown EJ, August EM, Webb E, Stern R, et al. Knowledge and perception of STI/HIV risk among rural African-American youth: Lessons learned in a faith-based pilot program. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children and Youth. 2008;9(1):97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee N. Episcopalians divide again over electing gay bishop. The New York Times; May 5, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship KM, Bray SJ, Merson MH. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S11–S21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black families in therapy: Understanding the African American experience. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: What have we learned? AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15(1):49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: Evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 2007. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CJ. The boundaries of blackness: AIDS and the breakdown of black politics. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, Scribner R. An STD/HIV prevention intervention framework. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2000;14(1):37–45. doi: 10.1089/108729100318118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne-Beasley T, Schoenbach VJ. The African-American church: A potential forum for adolescent comprehensive sexuality education. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford I, Allison KW, Robinson WL, Hughes D, Samaryk M. Attitudes of African-American Baptist ministers toward AIDS. Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20:304–308. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, editors. The handbook of social psychology. McGraw-Hill; Boston, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson S, Tebbe N, Van Haitsma M, Laumann EO. Religion and the politics of sexuality. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 2001;30(1):3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Francis SA, Liverpool J. A review of faith-based HIV prevention programs. Journal of Religion and Health. 2008;48:6–15. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE. Stigma as an obstacle to AIDS action: The case of the African American community. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42(7):1113–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Genrich GL, Brathwaite BA. Response of religious groups to HIV/AIDS as a sexually transmitted infection in Trinidad. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. New rules of sociological method. Hutchinson; London: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of a spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein L. Openly gay man is made a bishop. The New York Times; Nov 3, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. AIDS and stigma. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42(7):1106–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: Prevalence and trends, 1991–1999. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(3):371–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, Farina A, Hastorf AH, Markus H, Miller DT, Scott RA. Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. W.H. Freeman; New York, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Klein SJ, Karchner WD, O'Connell DA. Interventions to prevent HIV-related stigma and discrimination: Findings and recommendations for public health practice. Journal of Public Health Management Practice. 2002;8(6):44–53. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin BA, Mayer E, Keysar A. American religious identification survey, 2001. The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, NY.; New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln CE, Mamiya L. The Black church in the African-American experience. Duke University; Durham, NC: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: A review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;2(suppl 2):S67–S79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz JP. The role of churches in helping adolescents prevent HIV/AIDS. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Education for Adolescents and Children. 1997;1(2):45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nyblade L, Pande R, Mathur S, MacQuarrie K, Kidd R, Banteyerga H, et al. Disentangling HIV and AIDS stigma in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia. The International Center for Research on Women; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Piot P. AIDS: From crisis management to sustained strategic response. Lancet. 2006;368:526–530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin RH, Billingsley A. The role of the black church in working with black adolescents. Adolescence. 1994;29(114):251–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumartojo E. Structural factors for HIV prevention: Concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S3–S10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tesoriero JM, Parisi DM, Sampson S, Foster J, Klein S, Ellemberg C. Faith communities and HIV/AIDS Prevention in New York State: Results of a statewide survey. Public Health Reports. 2000;15:544–556. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.6.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Billingsley A, Caldwell C. The characteristics of northern black churches with community outreach programs. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(4):575–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.4.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrell CO, Klein SJ, Gieryic SM, Devore BS, Cooper JG, Tesoriero JM. Early results of a statewide initiative to involve faith communities in HIV prevention. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2008;14(5):429–436. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000333876.70819.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]