Abstract

Background

Child abuse continues to be a social menace causing both physical and emotional trauma to benevolent children. Census has shown that nearly 50–75% of child abuse include trauma to mouth, face, and head. Thus, dental professionals are in strategic position to identify physical and emotional manifestations of abuse.

Aim

A cross-sectional survey was undertaken to assess knowledge and attitude of dental practitioners regarding child abuse and to identify the barriers in reporting the same.

Methods

With prior consent, a 20-question survey including both multiple choice and dichotomous (Yes/No) questions was mailed to 120 state-registered general dentists, and the data collected were subjected to statistical analysis.

Results

Overall response rate to the questionnaires was 97%. Lack of knowledge about dentist's role in reporting child abuse accounted to 55% in the reasons for hesitancy to report. Pearson chi-square test did not show any significant difference between male and female regarding reason for hesitancy to report and legal obligation of dentists.

Conclusion

Although respondent dentists were aware of the diagnosis of child abuse, they were hesitant and unaware of the appropriate authority to report. Increased instruction in the areas of recognition and reporting of child abuse and neglect should be emphasized.

Keywords: Child abuse, Physical abuse, Dentists, Child protection training

1. Introduction

Child abuse was practiced in the form of infanticide among Greeks and Romans, but was thoroughly masqueraded in archival societies. It was uncovered in 1962, with the conception of the term “battered child syndrome” by Kempe et al. to describe children presenting with numerous unexplained injuries.1 It is arduous to get exact stats of such vignettes, as it is a secretive behavior, and each territory compiles its own figures based on local definitions. Nevertheless, reporting levels do not mirror incidence levels.2

To aid in diagnosing and reporting of child abuse, below mentioned are some accepted definitions of the same:

-

•

Child maltreatment, sometimes referred to as child abuse and neglect (CAN), includes all forms of physical and emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, and exploitation that result in actual or potential harm to a child's health, development, or dignity.3

-

•

World Health Organization has defined child abuse as “Every kind of physical, sexual, emotional abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, commercial or other exploitation resulting in actual or potential harm to the child's health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power” (World Health Organization, 1999).4

Most cases of child maltreatment fall into the 3 basic categories: (1) neglect; (2) physical abuse; and (3) sexual abuse.5 The blemishing long-term effects of child abuse predispose victims to become violent adult offenders and facing adaptation problems in school and society.2

Interventional strategies targeted at resolving this problem face complex challenges.6 Many surveys have shown that 50–77% of the abuse cases involve head and neck region, thus placing oral health care workers in a strategic position to detect, diagnose, document, and report to appropriate authorities.2 Due to the incorporation of this subject into the curricula of undergraduate dental education of dental schools, there has been a recent rise in the awareness of dental health professionals regarding the same.7, 8, 9 Despite this training, it is found that abuse is still being under-reported by health care professionals, including the dental community.10 The first documented evidence of dentists failing to report child maltreatment was reported by the American Dental Association in 1967, stating that among 416 reported cases of child abuse in New York State, none was reported by a dentist. Lack of knowledge of dentists in this area was documented as the reason for under reporting.11, 12 Although this subject is vital, most of the professionals still ignore the correct attitude toward suspicious cases of abuse.

Thus, the undermentioned study was stipulated to analyze the level of knowledge and attitudes among dental practitioners regarding child abuse, to identify barriers that prevent the reporting of suspected cases, and to assess the need for associated training.

2. Methodology

After obtaining approval from the Ethical Committee of the institute, this study was conducted at Kothiwal Dental College and Research Centre, Moradabad, India.

Only general dental practitioners with active state dental licensure were included in this study. However, dentists without state licensure were excluded. While the intent was to maximize the representativeness of the sample, the results analyzed were only those from the dentists who responded. Prior to distribution of questionnaire, written consent was obtained stating that responses would be kept anonymous and confidential. A 20-question survey was distributed to 120 General dentists of Moradabad city. The questionnaire consisted of multiple-choice as well as dichotomous yes-no questions. No identification was requested for either the name or location of those completing the survey.

First part of the questionnaire consisted of questions on the demographics of the responding practitioners.

The Second section consisted of questions to assess the practitioner's knowledge regarding detection of such cases, risk factors for child abuse, manifestations and indicators of physical abuse, the history of suspected child abuse cases from their practice, change in behavior of such vignettes, and awareness of laws. The third section included questions regarding the attitude of practitioners’ toward reporting of suspected cases of CAN. Fourth section pertained to barriers in reporting of such vignettes and need for training in the same issue. Data received were decoded, tabulated, and recorded in an Excel database, and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) version 18 software.

3. Results

Questionnaire responses were tabulated, and percent frequency distributions for responses to each item were computed. Pearson chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used to analyze two categorical or nominal variables. The level of significance was set at 0.05. There were 1914 responses to the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 96.7%.

Demographics of the practitioner revealed that out of respondent general dentists, 47% were male, 52% identified themselves as females. Nearly 42.2% (N = 46) of the dentists were practicing in a city or suburban area and 55% of the respondents were associated with an institution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and knowledge of dentists.

| Age | |

| More than 30 | 51.4 |

| 26–30 yrs | 44 |

| 22–25 yrs | 4.6 |

| Experience | |

| A more than 9 yrs | 94.5 |

| B 5–9 yrs | 1.8 |

| C 1–4 yrs | 3.7 |

| Hours of educational training for child abuse were given in curriculum | |

| A None | 54.1 |

| B 1 hr | 34.9 |

| C 2 hr | 4.6 |

| D More than 2 hr | 6.4 |

| Knowledge/experience | |

| Cases of child abuse come across | |

| A None | 32.7 |

| B 1–5 | 60.7 |

| C 6–10 | 4.7 |

| D More than 10 | 1.9 |

| Ability to distinguish b/n AI and CA* | |

| A Yes | 89.7 |

| B No | 10.3 |

| Awareness of any law to prevent child abuse | |

| A Yes | 68.2 |

| B No | 31.8 |

| In which age group you know/expect child abuse to be more | |

| A Less than 3 yrs | 11.4 |

| B 3–6 yrs | 38.1 |

| C 7–12 yrs | 49.5 |

| D More than 12 yrs | 1 |

| Commonly observed abuser can be | |

| A Parent | 33.7 |

| B Teacher | 24 |

| C Elder sibling | 1.9 |

| D Relative | 21.2 |

| E Unknown | 18.3 |

| Wish to counsel victim or abuser | |

| A Yes | 95.4 |

| B No | 4.6 |

| Wish to attend any kind of educational programme | |

| Yes | 99.1 |

| No | 0.9 |

CA – Child Abuse.

3.1. Knowledge/experience

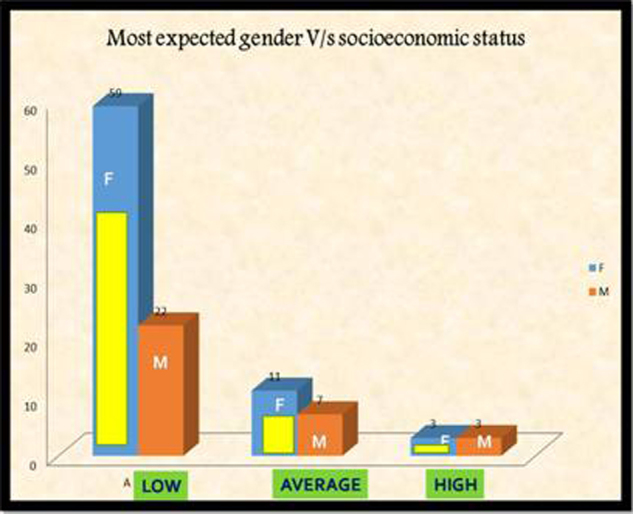

Questions pertaining to knowledge of dentists showed that nearly 89.7% of them were able to distinguish between accidental injury and physical abuse (Table 1). 68.2% were aware of any law to prevent child abuse (Table 1). Low SES (77.1%) was recognized as major group facing the same with larger percentage of infliction among female children (69.5%) (Graph 1).

Graph 1.

Most expected gender vs socioeconomic status for child abuse.

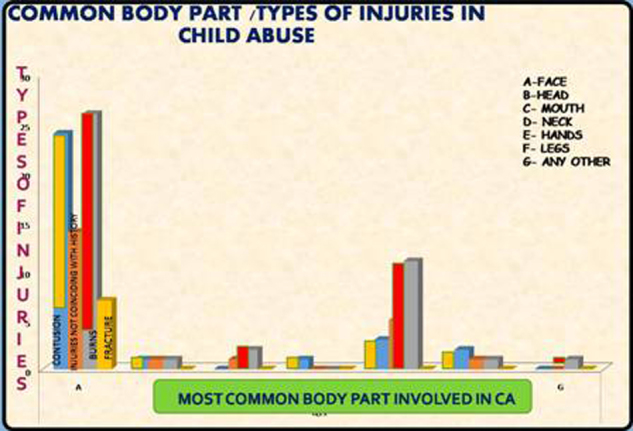

Face was identified as the most common (68.9%) and neck and legs as least common (1%) body parts, and with burns being the most type of injury involved (40.4%) (Graph 2). Majority of the abusers were found to be parent (33.7%) and least was elder sibling (1.9%). 45.5% of the dentists believed such children to be uncooperative, 23.8% believed to be stoic and only 5.9% believed such children to be aggressive in the dental clinic.

Graph 2.

Common body part vs types of injuries in child abuse.

3.2. Attitude

Attitude of dentist toward reporting of child abuse cases revealed that 46.3% of the dentists’ opinion was to report such vignettes to police (Table 2). 53.8% of the respondents’ temperament was to report only diagnosed cases of child abuse (Table 2). Applying Pearson chi-square test among gender of the respondent and commonly observed gender of abused children showed significant result (Table 3).

Table 2.

Attitude of dentists.

| Likelihood of agency to report | Percent |

|---|---|

| Attitude of dentists toward reporting of child abuse | |

| A To police | 46.3 |

| B To parents | 25.9 |

| C Childline help no | 26.9 |

| D Any other | 0.9 |

| Believed their legal obligation to report | |

| Suspected cases of child abuse | 39.6 |

| Diagnosed cases of child abuse | 53.8 |

| Did not know | 6.6 |

| Barriers to report | |

| Reasons for hesitancy to report | |

| Lack of adequate history | 42.1 |

| Lack of knowledge about dentist role in reporting | 43.9 |

| Concern about the effect it may have on their practice | 14 |

Table 3.

Comparison among gender of respondent and gender of abused child.

| Count | Gender of respondent |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | |

| Crosstab | |||

| Gender of abused child | |||

| Female | 26 | 45 | 71 |

| Male | 22 | 10 | 32 |

| Total | 48 | 55 | 103 |

| Pearson chi-square test | 9.151 | p-value | 0.002 |

p < 0.05 significant.

3.3. Barriers to report

Lack of knowledge about dentists’ role in reporting (51.4%) was identified as the major barrier in reporting, while only 14% were apprehensive about its effect on their practice (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Physical maltreatment to young children can vary from mild (a few bruises, welts, scratches, cuts, scars), moderate (numerous bruises, minor burns, a single fracture), or severe (large burn, central nervous system injury, multiple fractures, other life-threatening injury).14 Since, multitude of these injuries involve orofacial region, dentists can be the foremost to detect signs of physical abuse, sexual abuse, health care neglect, dental neglect, and safety neglect. Nevertheless, global statistics have shown under notification of the suspicious cases which might be due to the lack of information regarding the diagnosis and knowledge about the obligation of notifying suspected cases among various health professionals.13 Thus, a cross-sectional survey was undertaken to obtain information regarding the dentists’ knowledge and attitude regarding exigent issue of child abuse. The study consisted of self-report questionnaire, ensuring the confidentiality of the questionnaires, thereby granting more confidence and high response rate.15 Within the limitations of this study, the results provided an insight to the knowledge/experience and attitudes of general dentists of Moradabad city.

5. Response rate

Response rate of the present study was comparatively higher (96%) to previous studies (38%),5 and 68%.15

5.1. Knowledge/experience

The rate of detecting cases of child abuse by respondents in our study was higher (60%) in contrast to previous studies as 42% by Owais et al.,16 50% by Sonbol et al.,17 50% by Samer A. Bsoul5 and almost similar 59% by Al-Dabaan,4 78.7% by Marina Sousa Azevedo15 and 65% by Granville-Garcia.18 Increased awareness among dentists can be cited as the reason for greater detection rate of such cases.

5.1.1. Ability to diagnose child abuse cases

Among 89.7% of the respondents capable of diagnosing abuse vignettes, majority (55%) were associated with academic institute. This response is akin to the study done by Al Dabban et al. in which 41% were university-associated dentists.4 The reason cited for the same can be due to the fact that guild affiliated dentists are exposed to higher number of patients and are aptly equipped to deal such situation.15

5.1.2. Awareness of laws

In the present survey, 68.2% of the dentist were aware of any law to prevent child abuse in contrast to the study by Al-Buhairan et al., where only 22% of the dentists were conscious of United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) Article 19, or national policies addressing child maltreatment (United Nations Human Rights. Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989). Ignorance about the respective laws might contribute to the lower incidence of reporting.4

5.1.3. Population and gender group at risk

Synonymous to studies by Sonbol et al.17 (57%) and Al-Dabaan et al.4 (74.6%), our study also revealed that children of low socioeconomic status (77%) are more commonly predisposed to physical maltreatment. Parent unemployment, poverty and child maltreatment have been identified as risk factors for the same. Nevertheless, it is imperative for healthcare providers to recognize that child maltreatment is not rare in children from middle and high socioeconomic strata.4

Contrary to the previous studies by Sudeshni Naidoo and United Kingdom National Society, where more than 50% of the maltreatment cases occurred below 4 yrs of age, with boys being more commonly involved; present survey showed that children in the age group of 7–12 yrs (49%) and higher number of females (69%) are more susceptible to the misdemeanor.19 Biased social rituals might pave females more prone to the vultures of the crime.

5.1.4. Cognizance with physical indicators of child abuse

The dentist should be cognizant with signs of child abuse, as any injury with inconsistent history might finger toward physical aggression going on with the child.13 Most common type of child abuse injuries reported in present survey was Burns (40%) followed by orofacial injury (38.1%). Contrast results were obtained in a survey of Brazilian endodontists and John et al., where only 27% and 37% of the professionals, respectively, cited the lesions in head, neck, face, and mouth, while hematomas (48%) and behavior changes (48%) were the most signs reported.13 In some previous studies, bruises on the soft tissue of cheek and neck (81% – Al-Dabaan et al.4 and Owais et al.16) bruises on the toddler forehead (68%)4 and areas overlying bony prominences (79.2% – Hashim and Al-Ani20) were notified as the prevalent signs on victims’ body.

5.1.5. Common abuser

Congruent to Winship, present study also affirmed parent (33.7%) to be most probable abuser followed by relative (21.2%). While mother has been found to be the perpetrator in most of the cases; step parents and sibling offenders are also not prodigious.19

5.2. Attitude

5.2.1. Likelihood of agency to report

In precedent studies, professionals liked to discuss the matter within their professional circle or social worker.4 In the mentioned survey, 46.3% of the respondents believed it to report to police and only 26.9% of the respondents to the childhood helpline number, which is contrary to previous studies where contact of police was considered least desirable by most of the professionals.4, 21 This reveals that majority of the dentists are unaware of the appropriate agency to report and presence of communication gap between social welfare agencies and health care workers.

5.2.2. Legal obligation to report

In present study, more than 50% of dentists believed that their legal obligation is to report diagnosed cases of child abuse, 40% knew to report suspected cases and only 6% of the respondents did not know of their legal obligation. Contrast results were revealed by Samer A. Bsoul's past survey where majority of the responding dentists (84%) were aware of their legal obligation to report suspected cases of child abuse.5 Similar trend was followed in antecedent works where fewer dentists had recognized and reported suspicious cases of child physical abuse throughout their professional life.3, 24, 25, 26 In a Californian study, while 16% had suspected cases of child abuse only 6% genuinely reported to authorities.27 Former exclusive study by Granville-Garcia showed most (89.0%) suspected cases being reported.18

5.3. Barriers to report

Lack of knowledge about dentist role in reporting child abuse was cited as the most common barrier followed by lack of adequate history and least was their concern about effect on their practice. Conversely, some of the barriers reported in prior investigations are

| Barriers to report | Authors |

|---|---|

| Lack of adequate knowledge about abuse and dentists role in reporting | Samer A. Bsoul5 and Marina Sousa Azevedo15 |

| Lack of adequate history | Marina Sousa Azevedo15 |

| Fear of violence or unknown consequence toward the child | Al-Dabaan4 and Marina Sousa Azevedo15 |

| Lack of confidence in child protection services and their ability to handle such sensitive cases | Al-Dabaan4 and Marina Sousa Azevedo15 |

| Lack of certainty about the diagnosis’ | Marina Sousa Azevedo,15 Cairns et al.22 and Harris et al.23 |

| Lack of knowledge of referral procedures | Sonbol et al.17 |

| Fear of negative effects on the child's family | Al-Dabaan4 and Marina Sousa Azevedo15 |

| Family violence against dentists | Al-Dabaan4 |

| Confidentiality associated with reporting CAN** cases | Marina Sousa Azevedo,15 Owais et al.16 and Kilpatrick24 |

| Fears of a negative impact on dental practice, fear of litigation | Al-Dabaan4 and Marina Sousa Azevedo15 |

| Uncertainty about the consequences of reporting | Marina Sousa Azevedo15 |

| “It is not the dentist's responsibility” | Marina Sousa Azevedo15 |

CAN – child abuse and neglect.

Perhaps, dentists need to be better informed about how to recognize and gather information to explain children's unexplained physical wounds or emotional behaviors.

5.3.1. Child protection training

In accord to the present survey, 54% of the respondents reported that zero hours of education was allocated to this topic during training while 34.9% of the respondents told that only 1 hr was allocated. Harmoniously in prior studies, only 1.9% of the dental school professionals received child protection training.28

These findings suggest that most predoctoral dental programs in many countries devote inadequate level of instruction for dentists to diagnose and refer such cases. This level of instruction should be incremented to recognize the signs of abuse and how to report it.5

In comparison to prior studies by Al-Dabaan et al. and Al-Buhairan et al. where 92.9% and 69.3% of the respondents respectively wished to attend child protection training,29 in aforementioned survey, 99.1% of the respondents wanted to attend training for the same.

Therefore, from above-mentioned statistics, it can be drawn that professionals carry inadequate level of information to identify and diagnose child abuse, and if able to diagnose were benighted of the appropriate agency to report the matter.

5.4. Limitations

A large percentage of respondents in this study were from academics. Therefore, the results obtained might not necessarily be representative of the total population of dentists working in Moradabad district.

6. Conclusion

-

1.

Under-reporting of child abuse is still a significant problem in the dental profession.

-

2.

Children witnessing violence are at an increased risk of growing up to be abusers themselves. So, we as health professionals can play proactive role in breaking intergenerational vicious cycle of violence.

-

3.

Continued efforts by educational and government institutions should be brought to bear on this significant social and healthcare problem, whether through dental school curricula or continuing education courses.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Barton D., Schmitt B.D. Types of child abuse and neglect: an overview for dentists. Pediatr Dent. 1986;8(May (1)):67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsang A., Sweet D. Detecting child abuse and neglect — are dentists doing enough? J Can Dent Assoc. 1999;65:387–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adair S.M., Wray I.A., Hanes C.M. Perceptions associated with dentists’ decisions to report hypothetical cases of child maltreatment. Pediatr Dent. 1997;19:461–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Dabaan R., Newton J.T., Asimakopoulou K. Knowledge, attitudes, and experience of dentists living in Saudi Arabia toward child abuse and neglect. Saudi Dent J. 2014;26(July (3)):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bsoul S.A., Flint D.J., Dove S.B., Senn D.R., Alder M.E. Reporting of child abuse: a follow-up survey of Texas dentists. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25:541–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persaud D.I., Squires J. Abuse detection in the dental environment. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:459–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlin S.A., Polk K.K. Teaching the detection of child abuse in dental schools. J Dent Educ. 1985;49(9):651–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blain S.M. Abuse and neglect. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1991;19:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.da Fonseca M.A., Idelberg J. The important role of dental hygienists in the identification of child maltreatment. J Dent Hyg. 1993;67:135–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wachtel A. Health and Welfare Canada; Ottawa, ON: 1989. Child Abuse: A Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Dental Association From the states: legislation and litigation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1967;75:1081–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker D.B., Needleman H.L., Koatelchuck M. Child abuse and dentistry: orofacial trauma and its recognition by dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978;97:24–28. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Losso E.M., Marengo G., El Sarraf M.C., Baratto-Filho F. Child abuse: perception and management of the Brazilian endodontists. RSBO. 2012;9(January–March (1)):62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavalcanti A.L., Granville-Garcia A.F., de Brito Costa E.M.M., Correia Fontes L.B., Diniz de Sá L.O.P., Lemos A.D. Dentist's role in recognizing child abuse: a case report. Rev odonto ciênc. 2009;24(4):432–434. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azevedo M.S., Goettems M.L., Brito A. Child maltreatment: a survey of dentists in southern Brazil. Braz Oral Res. 2012;26(January–February (1)):5–11. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242012000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owais A.I.N., Qudeimat M.A., Qodceih S. Dentists’ involvement in identification and reporting of child physical abuse: Jordan as a case study. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2009;19(4):291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonbol H.N., Abu-Ghazaleh S., Rajab L.D., Baqain Z.H., Saman R., Al-Bitar Z.B. Knowledge, educational experiences and attitudes towards child abuse amongst Jordanian dentists. Eur J Dent Educ. 2011;16(1):158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2011.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granville-Garcia A.F., de Menezes V.A., Silva P.F.R.M. Maus tratos infantis: Perceção e responsabilidade do cirurgião dentista. Rev Odonto Cien. 2008;23(January–March (1)):35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudeshni Naidoo. Importance of oral and facial injuries in child abuse. www.unisa.ac.za/.../ASPJ2004-2-1-11-The-importance-of-Oral-and-facial-injuries-in-child-abuse.pdf

- 20.Hashim R., Al-Ani A. Child physical abuse: assessment of dental students’ attitudes and knowledge in United Arab Emirates. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2013;14:301–305. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas J.E., Straffon L., Inglehart M.R., Habil P. Knowledge and professional experiences concerning child abuse: an analysis of provider and student responses. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cairns A.M., Mok J.Y.Q., Welbury R.R. The dental practitioner and child protection in Scotland. Br Dent J. 2005;199(8):517–520. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris J.C., Elcock C., Sidebotham P.D., Welbury R.R. Safeguarding children in dentistry: 1. Child protection training, experience and practice of dental professionals with an interest in paediatric dentistry. Br Dent J. 2009;206(8):409–414. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilpatrick N.M., Scott J., Robinson S. Child protection: a survey of experience and knowledge within the dental profession of New South Wales, Australia. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1999;9(September (3)):153–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.1999.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos-Gomez F., Rothman D., Blain S. Knowledge attitudes among California dental care providers regarding child abuse and neglect. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129(March (3)):340–348. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazenbatt A., Freeman R. Recognizing and reporting child physical abuse: a survey of primary healthcare professionals. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(3):227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jessee S.A. Physical manifestations of child abuse to the head, face, and mouth: a hospital survey. J Dent Child. 1995;62:245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habib H.S. Pediatrician knowledge, perception, and experience on child abuse and neglect in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med J. 2012;32(3):236–242. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Buhairan F.S., Inam S.S., Al Eissa M.A., Noor I.K., Almuneef M.A. Self-reported awareness of child maltreatment among school professionals in Saudi Arabia: impact of CRC ratification. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(1):1032–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]