Abstract

Objective:

Hydrocephalus is a most common complication of tubercular meningitis (TBM). Relieving hydrocephalus by ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) placement has been considered beneficial in patient in Palur Grades II or III. The role of VPS placement in those of Grades III and IV is controversial, and general tendency is to avoid its use. Some authors have suggested that patient in Grades III and IV should receive a shunt only if their condition improves with a trial placement of external ventricular drain (EVD). However, recent studies suggest that VPS may be undertaken without the trial of an EVD. Our study prospectively evaluates the role of direct VPS placement in patient in Grades III and IV TBM with hydrocephalus (TBMH).

Materials and Methods:

This study was carried out on 50 consecutive pediatric patients of TBMH in Palur Grades III and IV from July 2013 to December 2014 in R.N.T. Medical College and M.B. Hospital, Udaipur, Rajasthan. All patients underwent direct VPS placement, without prior placement of EVD. The outcome was assessed at the end of 3 months using Glasgow Outcome Score.

Results:

The mean age of patients was 3.25 years (range, 3 months–14 years). Forty (80%) patients were in Grade III, and 10 (20%) were in Grade IV. Good outcome and mortality in Grade IV patients were 30% (3/10) and 10% (1/10), respectively; whereas in Grade III patients, it was 77.5% (31/40) and 0% (0/40), respectively. Twenty-five patients presented with focal neurological deficit at admission, which persisted in only 14 patients at 3 months follow-up. VPS-related complications were observed in 5 (10%) patients.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrates that direct VPS surgery could improve the outcome of Grades III and IV TBMH. Despite poor grade at admission, 80% patients in Grade III and 20% patients in Grade IV had a good outcome at 3 months follow-up. Direct VPS placement is a safe and effective option even in a patient in Grades III and IV grade TBMH with a low complication rate.

Keywords: Hydrocephalus, Palur Grade III and Grade IV, tubercular meningitis, ventriculoperitoneal shunt

Introduction

The indication and timing of surgical intervention for tubercular meningitis (TBM) with hydrocephalus (TBMH) remain controversial, and only a few studies have tried to address this issue previously. Although previously studies have shown age to be an independent prognostic factor in TBMH, there are very few studies dedicated to the pediatric population.[1,2] Shunt malfunction is also very common in children and is related partly to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein content, which may be very high in the majority of the cases. Although medical management remains the mainstay of therapy for TBM, hydrocephalus with impaired neurological function mandates surgical intervention either in the form of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS), external ventricular drain (EVD), or a third ventriculostomy.[3]

Timing of shunt procedure has also been found to affect the final outcomes of patients. Early shunting for moderate/sever noncommunicating hydrocephalus or communicating hydrocephalus in case of failed medical therapy in Stages I–III has a positive effect on morbidity and lead to favorable outcome.[1] However, the role of VPS placement in Grade IV patient is controversial. It also has been suggested that EVD is performed before VPS on Stage IV patients to determine the potential benefits of shunting. However, this approach has not been proven statically yet.[4]

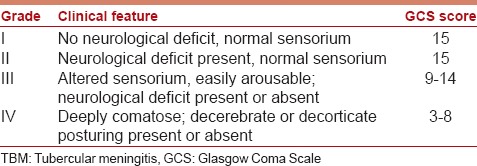

The grade of the patient at admission usually determines the management strategy. There is a various grading system for the patient of TBMH. One of the commonly used systems is the Vellore grading system proposed by Palur et al.[4] [Table 1]. The internal drainage of CSF, in the form of VPS, has been accepted as standard of care in patients presenting in good neurological grade (I and II).[4]

Table 1.

Palur grading system for TBM

Prolonged EVD is fraught with the risk of infections. Some recent studies have evaluated direct VPS placement (without an intervening EVD placement) in poor neurological grade patients of TBMH and found it an effective treatment option.[5,6,7]

Our study prospectively evaluated the role of direct VPS placement (without prior placement of EVD) in the patient in Grades III and IV TBMH and whether this strategy is associated with increased shunt complication.

Materials and Methods

A prospective cohort study was performed on children (age group: 3 months–14 years) with TBM Grades III and IV, who underwent placement of VPS in the Department of Neurosurgery at R.N.T. Medical College and M.B. Hospital, Udaipur, Rajasthan, during a period of 18 months from July 2013 to December 2014. A written informed consent was taken from parents/guardians of all patients, as applicable. The diagnosis of TBM was made on the basis of typical clinical, radiological, and CSF biochemistry, cytology, as well as positive sputum or CSF culture. Children were graded according to the grading system devised by Palur et al.[4] [Table 1], and only Grades III and IV children (age group: 3 months–14 years) were considered for this study. Children age <3 months and >14 years, suffering from pyogenic meningitis and, hemodynamically unstable patients were not included in this study.

The patient's symptoms, history of exposure to a known case of TB, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), focal neurological deficit (FND), and fundoscopic findings were noted. The patients were categorized into Palur grades. The microbiological, cytological, and biochemical findings of CSF from guarded lumber puncture were noted. The presence of hydrocephalus (Evan's ratio), periventricular lucencies, infarcts, basal exudates, and meningeal enhancement were noted based on the computed tomography (CT) scan. Duration between onset of illness and initiation of treatment was noted. The patient that were hemodynamically unstable and could not be taken up for an operative procedure, and those patients who were diagnosed to have pyogenic meningitis were excluded from the study, as EVD placement was done immediately to alleviate intracranial pressure (ICP).

All children received standard four drugs antitubercular therapy (ATT) (consisting of rifampicin, ethambutol, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide) according to body weight.[8] All of them were also put on prednisolone (1 mg/kg) for first 8–12 weeks of illness. The necessary supportive care was provided to the patients. Hemodynamically stable patients in Palur Grades III and IV were taken up for placement of a medium pressure Chhabra VPS. In view of the diagnosis of TBM and considering the likely high protein content in CSF, we used medium pressure valve in all patients. Only single dose of a second-generation cephalosporin, as per the patient's weight, was given at the time of skin incision.

All patients were evaluated immediately postoperatively, at discharge and at 3 months after VPS. GCS score and FNDs, if any, were noted the Glasgow Outcome Score (GOS) was used to assess the level of functional independence, at 3 months follow-up. GOS 1, 2, and 3 were considered as a poor outcome, while GOS 4 and 5 were considered as a good outcome. Noncontrast head CT scan was repeated 3 months after the VPS to observe the change in the size of ventricles. The incidence of shunt complication and requirement for shunt revision during this period was recorded.

Data are presented in descriptive from either as mean (standard deviation) or median in normally distributed and skewed variables, respectively. Normality of data was checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. For normally distributed data, means were compared using unpaired Student's t-test for two groups. For skewed data, Mann–Whitney test was applied. Qualitative or categorical variable was described as frequencies and proportions. Proportions were compared using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test whichever was applicable. The McNemar test was to analyze the probability of FND at 3 months follow-up. All statically tests were two-sided and the value P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

General characteristics

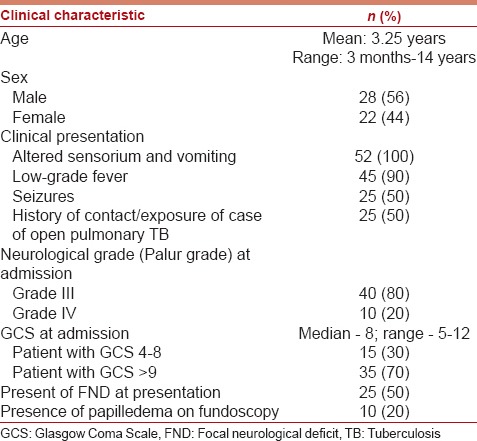

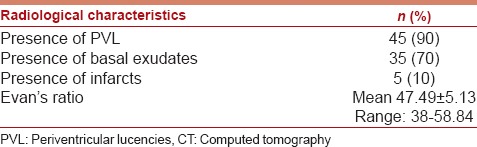

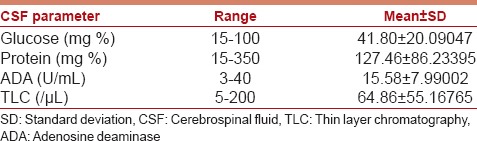

Fifty patients were included in the study; 22 (44%) females and 28 (56%) males. The mean age of the study group was 3.25 years (range, 3 months–14 years). Forty (80%) Patients were in Grade III, while 10 (20%) were in Grade IV. The GCS score of patients at admission ranged from 4 to 12, with a median score of 8. The clinical profile of the patient is detailed in Table 2. The radiological profile and CSF analysis profile of the study group are detailed in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 2.

The clinical profile of 50 patients included in the study

Table 3.

Radiological profile of the study group on CT finding

Table 4.

CSF analysis of study group

Outcome at 3 months follow-up

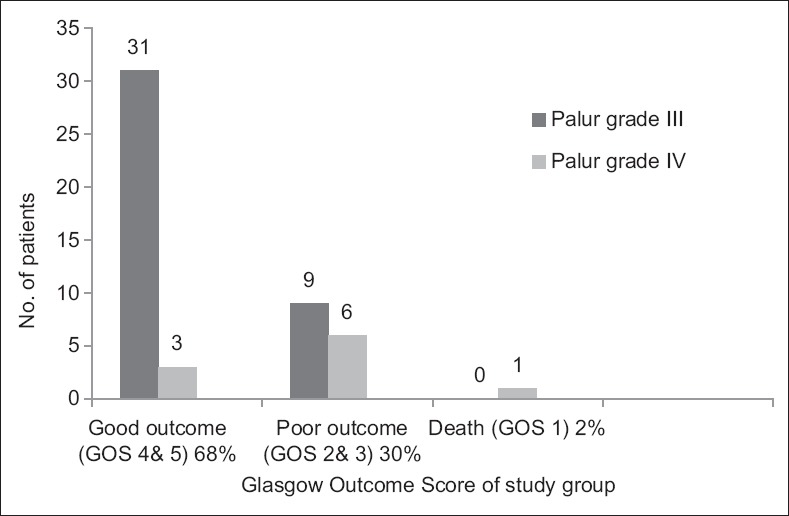

The outcome was assessed at 3 months follow-up. Thirty-four (68%) patient had good outcome whereas 15 (30%) patient had a poor outcome. Good outcome was observed in 77.5% (n = 31) patients in Grade III, whereas in only 30% (n = 3) patients in Grade IV. Mortality in Grade IV patients was 10% (n = 1), whereas in Grade III patients it was only 0% (n = 0). The difference in the outcome of Grades III and IV patients at the end of 3 months was statistically significant by the Chi-square test (P = 0.004). The outcome of the study is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Outcome of study group at 3 months after ventriculoperitoneal shunt

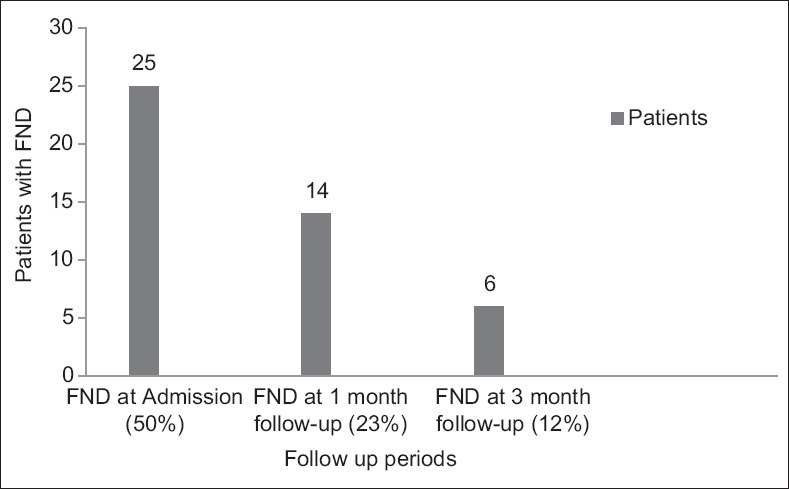

FNDs were observed in 25 (50%) patients at admission. However, these persisted in 14 (23%) patients at 1 month and in 6 (12%) patients at 3 months follow-up. The decrease in the number of patients with FNDs at presentation, at 1 month (P = 0.01) and at 3 months (P = 0.00), was statistically significant [McNemar test; Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Focal neurological deficit in study group during follow-up

Papilledema was seen in 20% (n = 10) patients at presentation, which resolved in 6 patients at 3 months follow-up.

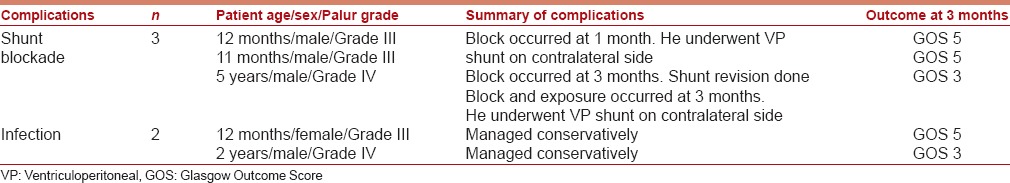

Complications

VPS-related complications were observed in 5 (10%) patients in the postoperative period. They were as follows: Shunt blockade/malfunction (3 patients), shunt infection (2 patients), the summary of the complications is detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of shunt complications along with outcome of patients whom the complications occurred

Shunt blockade

One patient developed shunt block within 4 weeks of the VPS. He underwent placement of another VPS on the contralateral side. The second patient developed shunt block, 3 months after surgery and had a good outcome at 3 months. The third patient developed shunt block and shunt exposure 3 months after surgery. He underwent placement of VPS on contralateral site and had a poor outcome at 3 months. The incidence of shunt block was 6%. The CSF profile of patients who suffered shunt blockade was not significantly different from that of the rest of the study group.

Shunt infection

Two patients developed shunt infection. Both were managed conservatively. One patient had a poor outcome (GOS score of 3) at 3 months. The other patient had a good outcome (GOS score of 5) at 3 months. The overall incidence of shunt infection was 4%.

Discussion

Hydrocephalus is one of the most common complications of TBM. It is evident that hydrocephalus is more common in children with TBM compared to adult with average incidence 71% in children and only 12% in adult. Early shunting tends to have a positive effect on morbidity for patients with severe hydrocephalus.[1,9] The fear of disseminating the tuberculous disease through such shunt systems was dispelled by reports by Bhagwati[10] and others.[7]

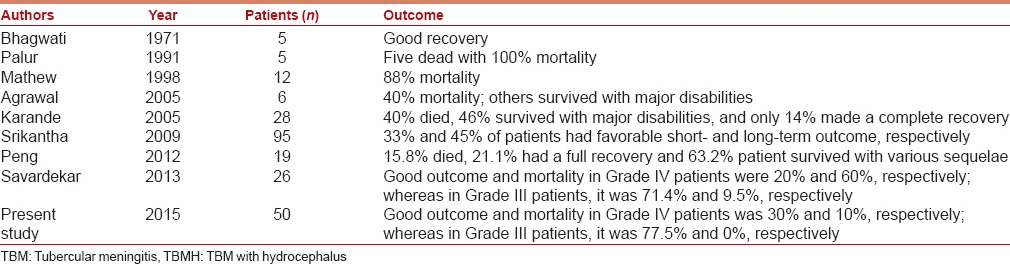

Although VPSs have generally been considered beneficial in Grades II and III TBMH.[2,4,11] Their role in patient in Grade IV is controversial, and general tendency is to avoid using it. Table 6 summarizes literature on the outcome of shunt surgery for Grades III and IV TBMH patients from 1971 to 2013. Past studies noted a high mortality rate that varied from 40% to 100% of the survivors. The majority were left with permanent neurological sequel,[4,11] except for 5 patients with good outcomes reported by Bhagwati.[10]

Table 6.

The outcome of patients with Grade III and IV TBMH who underwent shunt surgery in the literature

The outcome reported in patients with poor-grade TBM remains dismal across most series.[2,4,12] Some authors have recommended that patients in Grade IV should receive an EVD first, and then need for shunt surgery can be determined based on their response. Placing an EVD exposes patients to the risk of infection. In this study, all patients were in the pediatric population and were subjected to an internal drainage, i.e. VPS without an intervening external drainage, Along with ATT, steroids, and supportive care.

Our study was a prospective study which included patients of TBMH presenting in poor neurological grade defined as Palur Grades III and IV. All patients were followed up at 3 months after surgery, clinically as well as radiologically for assessing the impact of VPS on the course of the disease. The number of patients in Grade IV status was 10, which is a small number and thus adversely affects the significance of the study in laying guidelines for such patients.

Outcome at 3 months follow-up

The outcome of patients presenting in Grade III status was as follows: 77.5% (n = 31) were functionally independent, 22.5% (n = 9) had severe disability, and only 0% (n = 0) died. Palur et al., in their series, report a good outcome in 26% patients, while the mortality rate was 51.9%.[4] Mathew et al. have reported the good outcome in 55% (11/20) patients, with mortality was seen in 10% (2/20) patients.[11] Agrawal et al., in their series of 15 patients in Grade III, report a good outcome in 40% patients.[2] Savardekar et al., in their series of 26 patients, reports a good outcome in 71.4% patients in Grade III.[12] The mortality in various series in Grade III patients has been reported to range from 6.9% to 51.8%.[1,4,11,13] In the present series, mortality rate for patients presenting in Grade III is 0, and Grade IV is 10% which was very less than that reported in most series, with a large majority of patients having a good and functionally viable outcome. This can be attributed to the immediate treatment offered to these patients in the form of ATT, steroids, supportive care, and a VPS.

For patients presenting in Grade IV, mortality rates of 16.6–100% have been reported.[1,4,11,13] The mortality for such patients very low at 10% (n = 1) in our series. Only three patients in Grade IV status seemed to benefit from shunt placement. Nine patients are survived, six of them with severe disability (GOS score of 3), while another three was with moderate disability, but functionally independent (GOS score of 4), at the end of 3 months. Palur et al. have reported a mortality rate of 100% in Grade IV patients (n = 7).[4] Mathew et al. document mortality in 11 of their 12 patients in Grade IV status.[11] Agrawal et al. report a poor outcome in all six patients in Grade IV status.[2] Srikantha et al. have noted favorable outcome in 33% Grade IV patients in the short-term (at discharge) and in 45% of them in the long-term (at 3 months).[13] Our results are similar to that of Savardekar et al. even though the number of patients in Grade IV in our study is more than Savardekar et al. Peng et al., in their study of 19 patients in Grade IV undergoing VPS (17 had a direct VPS, and 2 had it after EVD placement, so that biochemical parameters could be corrected), show a full recovery in 4 patients, slight sequelae in eight, severe sequelae in four, and mortality in three patients.[14] In view of the 90% (n = 9) survival rate in such patients in our series, we suggest that direct VPS is warranted, if patient is deemed fit for undergoing surgery. At the same time, we underline the need for including a larger number of Grade IV patient's in future prospective trials to ratify VPS placement in them. A statistically significant difference was noted in the number of patients who had focal deficit at admission (50%, n = 25) and at 3 months (12%, n = 6). Lamprecht et al. noted poor outcome in 52.4% patients who presented with hemiparesis.[1] In our study, 40% (10/25) patients presenting with focal deficit had a poor outcome. The difference in the outcome of both groups (FND present at admission and FND absent at admission) was not statistically significant. Thus, we observed that the presence of FND does not adversely affect the outcome in patients of TBMH.

Factors affecting outcome of patients

There was a statistically significant association between grade at admission and outcome at 3 months follow-up (P = 0.048). None of the other variables studied (for example, age, duration of illness, GCS score at presentation, presence of FNDs, CSF cell count, CSF protein concentration, ADA levels, Evan's ratio for hydrocephalus, and PVL) had an association with outcome in our patients.

Misra et al. have shown that hydrocephalus at presentation is an independent factor in determining the outcome at the end of 3 months.[6] In our results, Evan's ratio at admission for the poor outcome group (52.35 ± 5.24%) and the good outcome group (44.88 ± 7.42%) was comparable. The Presence or absence of hydrocephalus may thus be a deciding factor for the outcome, but the degree of hydrocephalus does not appear to be associated with the outcome.

PVL on CT scan represents transependymal CSF absorption and is a marker of raised intracranial tension. Bullock and Van Dellen have considered PVL to be an unreliable marker for TBM.[5] Our study also showed no association between the presence of PVL and outcome in Grades III and IV patients of TBM.

Infarcts on the preoperative CT scan were observed in 5 patients. All had a moderate disability but was functionally independent (GOS score of 4) at the end of 3 months. Lamprecht et al. have reported a uniformly poor prognosis in 10 cases of TBM, who presented with infarcts on CT scan.[1] Schoeman et al. have also noted a uniformly poor prognosis in patients with basal ganglia infarction.[15] The small number of patients (n = 5) in the infarcts group meant that we could not analyze the association with outcome meaningfully.

The mean CSF protein concentration and CSF cell count were marginally higher in the poor outcome group as compared to the good outcome group, but it was not statistically significant. Proteinaceous debris in CSF is known to result in shunt block and may, therefore, dictate a poor outcome.[11] In our study group, only three patients suffered shunt blockage. The CSF analysis of these 3 patients, in terms of protein concentration and cell count, was comparable to that of the rest of the study group.

Complications

Complications related to surgery were seen in 5 patients. In the study by Agrawal et al., shunt-related complications occurred in 11 out of 37 children and three children underwent multiple shunt revisions.[2] Lamprecht et al. report a high complication rate of 32.3%, in their series of 65 patients of poor grade TBMH, shunt infection, and shunt obstruction accounting for the majority of the complications.[1] Peng et al. report a shunt complication rate in 6 out of 19 patients in Grade IV status undergoing shunt surgery.[14] Savardekar et al. report a complication rate 23.1% in their series of 26 patients of TBM Grades III and IV, shunt obstruction, and shunt infection accounting for the majority of the complications.[12] Thus, the complication rate seen in our study is lower than that reported in literature for cases of TBMH.

Poor outcome was observed in 40% of patients who suffered any complication. We feel that complications related to therapy in these severely disabled patients may cause further deterioration in their outcome and hence they should be avoided at all costs.

The incidence of shunt infection was 4% (n = 2) in our study, which is less than the 13–14% infection rate reported in literature.[1,13,14] The plausible reason for this is that though VPSs were carried out on an emergency basis in our study, this was done in an operating room that was used exclusively for this purpose and strict aseptic precautions were ensured during the procedure. Choux et al., however, have reported an annual shunt infection rate of 1.04%, though this study did not exclusively include patients of TBM.[16]

The outcome in Grades III and IV patients of TBMH is determined not only by the presence of raised ICP but also by the development of endarteritis or vasculitis with consequent brain infarcts.[4] Bullock and Van Dellen have mentioned endarteritis of perforating arteries to result in infarction and thus deteriorate the neurological status of such patients.[5] CSF diversion helps in reducing poor outcome and mortality by mitigating raised ICP in these patients. The total outcome of these patients may be dependent on the efficacy of ATT and steroids, and the resolution of meningitis and endarteritis but timely CSF diversion definitely optimizes the outcome. Patients of TBMH require long-term CSF diversion and functional VPS placement is the final goal as the neurological recovery takes time. Offering a functional VPS at the earliest in poor grade patients prevents wastage of critical time needed for neurological recovery. Since the improvement after CSF diversion may take many days or even weeks, and prolonged EVD is fraught with the risk of infections, direct shunt placement probably gives these patients the best chance of improvement.

There are several limitations in this study including no control group, relatively short follow-up duration, and no data on other kind of surgery such as endoscopic third ventriculostomy[17] or lumboperitoneal shunt are available.[18]

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrated improved outcomes even in Grade IV TBMH managed with VPS placement, ATT and steroids. VPS may be inserted without any intervening external drainage. Our study, showing 77.5% patients being functionally independent at 3 months and no mortality rate (0%) in Grade III patients, and showing 30% patients being functionally independent at 3 months and 10% mortality rate in Grade IV patients proves that this strategy is safe and effective. in the form of VPS, may be considered as the first line of treatment, if patient is deemed fit for surgery, as our study compares favorably with the reports in literature of Grade IV patients that were treated with EVD followed by a VPS. As seen in our study, if 3 patients in 10 is functional independent at 3 months, it is definitely worth the effort. Our study shows that the complications encountered with this strategy, are within acceptable limits, given the poor neurological status and general condition of these patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lamprecht D, Schoeman J, Donald P, Hartzenberg H. Ventriculoperitoneal shunting in childhood tuberculous meningitis. Br J Neurosurg. 2001;15:119–25. doi: 10.1080/02688690020036801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal D, Gupta A, Mehta VS. Role of shunt surgery in pediatric tubercular meningitis with hydrocephalus. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:245–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonathan A, Rajsekhar V. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy for chronic hydrocephalus after tubercular meningitis. Surg Neurol. 2005;63:32–5. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palur R, Rajshekhar V, Chandy MJ, Joseph T, Abraham J. Shunt surgery for hydrocephalus in tuberculous meningitis: A long-term follow-up study. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:64–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.1.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullock MR, Van Dellen JR. The role of cerebrospinal fluid shunting in tuberculous meningitis. Surg Neurol. 1982;18:274–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(82)90344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misra UK, Kalita J, Srivastava M, Mandal SK. Prognosis of tuberculous meningitis: A multivariate analysis. J Neurol Sci. 1996;137:57–61. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajshekhar V. Management of hydrocephalus in patients with tuberculous meningitis. Neurol India. 2009;57:368–74. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.55572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkataramana NK. Hydrocephalus Indian scenario – A review. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6(Suppl 1):S11–22. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.85704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemaloglu S, Ozkan U, Bukte Y, Ceviz A, Ozates M. Timing of shunt surgery in childhood tuberculous meningitis with hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;37:194–8. doi: 10.1159/000065398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhagwati SN. Ventriculoatrial shunt in tuberculous meningitis with hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:309–13. doi: 10.3171/jns.1971.35.3.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathew JM, Rajshekhar V, Chandy MJ. Shunt surgery in poor grade patients with tuberculous meningitis and hydrocephalus: Effects of response to external ventricular drainage and other variables on long term outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:115–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savardekar A, Chatterji D, Singhi S, Mohindra S, Gupta S, Chhabra R. The role of ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement in patients of tubercular meningitis with hydrocephalus in poor neurological grade: A prospective study in the pediatric population and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:719–25. doi: 10.1007/s00381-013-2048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srikantha U, Morab JV, Sastry S, Abraham R, Balasubramaniam A, Somanna S, et al. Outcome of ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement in Grade IV tubercular meningitis with hydrocephalus: A retrospective analysis in 95 patients. Clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:176–83. doi: 10.3171/2009.3.PEDS08308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng J, Deng X, He F, Omran A, Zhang C, Yin F, et al. Role of ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery in grade IV tubercular meningitis with hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:209–15. doi: 10.1007/s00381-011-1572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoeman JF, Van Zyl LE, Laubscher JA, Donald PR. Serial CT scanning in childhood tuberculous meningitis: Prognostic features in 198 cases. J Child Neurol. 1995;10:320–9. doi: 10.1177/088307389501000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choux M, Genitori L, Lang D, Lena G. Shunt implantation: Reducing the incidence of shunt infection. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:875–80. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.77.6.0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chugh A, Husain M, Gupta RK, Ojha BK, Chandra A, Rastogi M. Surgical outcome of tuberculous meningitis hydrocephalus treated by endoscopic third ventriculostomy: Prognostic factors and postoperative neuroimaging for functional assessment of ventriculostomy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;3:371–7. doi: 10.3171/2009.1.PEDS0947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yadav YR, Pande S, Raina VK, Singh M. Lumboperitoneal shunts: Review of 409 cases. Neurol India. 2004;52:188–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]