Abstract

Cranial sonography continues to hold an important place in neonatal care. Attributes favorable to sonography that make it almost indispensable for routine care of the newborn includes easy access, low cost, portability, lack of ionizing radiations and exemption from sedation or anaesthesia. Cranial sonography has highest impact in neonates suspected to have meningitis and its complications; perinatal ischemia particularly periventricular leukomalacia (PVL); hydrocephalus resulting from multitude of causes and hemorrhage. Not withstanding this, cranial sonography has yielded results for a repertoire of indications. Approach to cranial sonography involves knowledge of the normal developmental anatomy of brain parenchyma for correct interpretation. Correct technique, taking advantage of multiple sonographic windows and variable frequencies of the ultrasound probes allows a detailed and comprehensive examination of brain parenchyma. In this review, we discuss the technique, normal and variant anatomy as well as disease entities of neonatal cranial sonography.

Keywords: Brain, cranial, neonatal, ultrasound

Introduction

Cranial sonography is an important part of neonatal care in general, and high-risk and unstable premature infants, in particular. It allows rapid evaluation of infants in the intensive care units without the need for sedation and with virtually no risk. Expectedly, sonography represents an ideal imaging modality in neonates due to its portability, lower cost, speed, and lack of ionizing radiations. Although there are numerous indications for cranial sonography, it appears to be most useful for detection and follow-up of intracranial hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, and periventricular leukomalacia (PVL).[1] Besides, it allows accurate follow-up of certain entities diagnosed by prenatal sonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) namely central nervous system (CNS) malformations, infection, and masses. However, MRI scores over cranial sonography when major anomalies are present. Although not as commonly applied as B-mode imaging, color and spectral Doppler ultrasound of cranial blood flow is valuable for evaluation of cystic lesions including a vascular lesion, extra-axial collections and in differentiating normal vascular structures from clots.[2]

Technique

High-resolution imaging of the cranium requires high-frequency transducers (5–7.5 MHz). Wider far filed of view is provided by a sector transducer. Linear array, higher frequency transducers (7–12 MHz) are especially useful for near-field scanning, recommended for evaluation of extra-axial collections, superior sagittal sinus thrombosis, cerebral edema, and gyral-sulcal anatomy [Figure 1] in suspected migrational anomalies.[3] These transducers are also useful for scanning through the posterior fontanelle, mastoid fontanelle and for foramen magnum approach [Figure 2]. High-quality images are obtained by holding the transducer firmly between the thumb and index finger and resting the lateral aspect of the hand on the infant's head to ensure stability. Need for maintaining body temperature of the neonate cannot be overemphasized. Aseptic precautions are equally important and achieved by hand washing and transducer cleansing (with a manufacturer-approved disinfectant) between examinations.

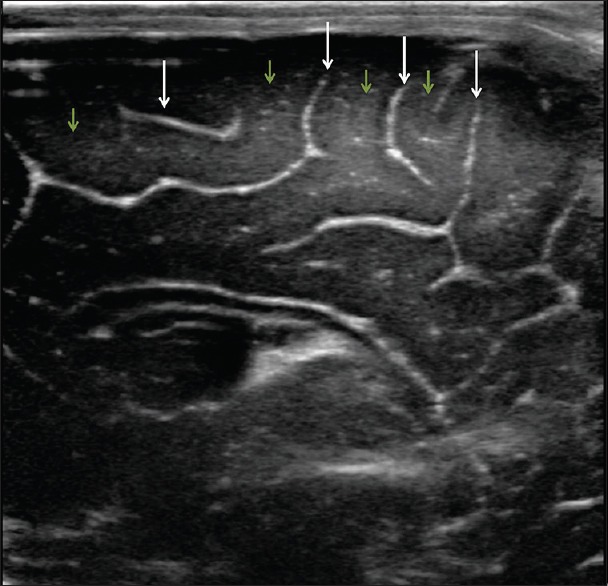

Figure 1.

High resolution image of the brain shows the normal appearance of the sulci (arrows) and gyri (short arrows)

Figure 2.

Foramen magnum view reveals high resolution image of the posterior fossa. CH: Cerebellar hemisphere; V: Vermis; Short arrow: Brainstem; Long arrow: Fourth ventricle

Windows for examination

Most cranial sonographic examinations are performed in coronal and the sagittal planes, through the anterior fontanelle that remains useful for scanning for 12–14 months of age. Posterior and mastoid fontanelles provide a better window for evaluation of posterior fossa structures.[4] However, they afford a useful window for a limited age only, i.e., up to 6 months. However, these views are indispensable for evaluation of posterior fossa malformations as they provide highly detailed views of the cerebellum, fourth ventricle, cisterna magna, and upper spinal canal [Figure 1].

Planes of examination

Coronal and sagittal planes are the most useful imaging planes for cranial sonography and allow a comprehensive brain examination.[5] Imaging in both these basic planes is recommended; if either plane is not scanned, pathology may be missed or false diagnosis may be offered, e.g., hyperechoic peritrigonal blush posterior and superior to the ventricular trigones on parasagittal views may be misinterpreted as early PVL if coronal imaging is not considered.[6] Similarly, hemorrhage may be missed without the posterior fossa sagittal views.

Normal Anatomy

Coronal

To demonstrate the anatomy in coronal plane, a minimum of six images are obtained by gently sweeping the probe from anterior to posterior.[7]

The most anterior image, just anterior to the frontal horns (FH) of the lateral ventricle (LV) demonstrates frontal lobes of the cerebral cortex and orbits [Figure 3a].

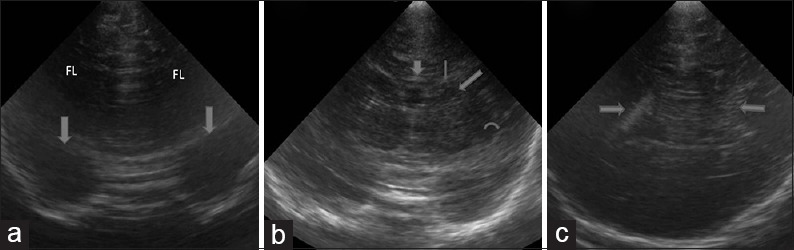

Figure 3.

Normal anatomy (a) normal anterior most coronal section reveals frontal lobes of the cerebrum and the orbit (arrows). (b) Normal coronal image at a level posterior to Figure 2 shows corpus callosum (short arrow), frontal horn (thin arrow), caudate (thick arrow) and middle cerebral artery in sylvian fissure (curved arrow). (c) Normal coronal image reveals the body of lateral ventricles with echogenic choroid plexus (arrow)

An image posterior to this shows the FH of the LV. The FH are indented laterally by caudate heads. Cingulate sulcus (CS), genu and anterior body of the corpus callosum (CC), and septum pellucidum (SP) are noted at this level from superior to inferior in the midline. Structures noted laterally are putamen, separated from the caudate by the internal capsule. More laterally, sylvian fissure is seen as an echogenic linear structure separating frontal from the temporal lobe. Inferior to this, internal carotid arteries bifurcate into anterior and middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) seen as echogenic structures [Figure 3b].

More posteriorly, structures visualized from superior to inferior in the midline are the body of the LV (on either side of the cavum septi pellucidi [CSP]), thalami (on either side of the third ventricle) and brainstem. Laterally, caudate and putamen are seen to be separated from the thalamus by the internal capsule. Further lateral is the centrum semiovale, the deep white matter of cerebral hemispheres.

Image posterior to the foramen of Monro, demonstrate CS, body of the CC, third ventricle between the anterior portions of the thalami and cerebellum. At this level, the body of the LV is rounded and show echogenic choroid plexus [Figure 3c].

The trigone of LV and occipital horns are visualized in more posterior images, filled almost entirely by choroid plexus. The part of CC visualized at this level is the splenium. Tentorium cerebelli is seen as echogenic structures on either side separating cerebellum from supratentorial structures.

In the most posterior image, occipital lobe along with the most posterior part of the occipital horns is visualized.

Sagittal imaging

The transducer is placed longitudinally across the anterior fontanelle and angled to either side. Interhemispheric fissure identifies the mid-sagittal plane. At this level, the LV is visualized with caudate nucleus and thalamus housed within its course from anterior to posterior. The junction of caudate and thalamus marks an important area, the caudothalamic groove, the most common site of germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH). Parasagittal images demonstrate a peripheral aspect of the ventricles and cerebral hemisphere including the temporal lobes. Hyperechoic blush postero-superior to the ventricular trigones is a normal finding on parasagittal images that should not be misinterpreted as suggestive of PVL.[6] It should not be visualized on scanning through the posterior fontanelle.

Normal Anatomic Variants

Cavum septi pellucidi and cavum vergae

During fetal life, there is a single continuous cystic structure in the midline of SP. The part anterior to the foramen of Monro is called CSP [Figure 4a] and the one posterior to it is cavum vergae. The closure of this structure occurs from back to front, starting at 6 months of gestation. At full term, no cystic component is noted in posterior part 97% of infants, so that there is only a CSP at birth.[8] Even this disappears by 3–6 months of age, however sometimes; the CSP may persist into adulthood.

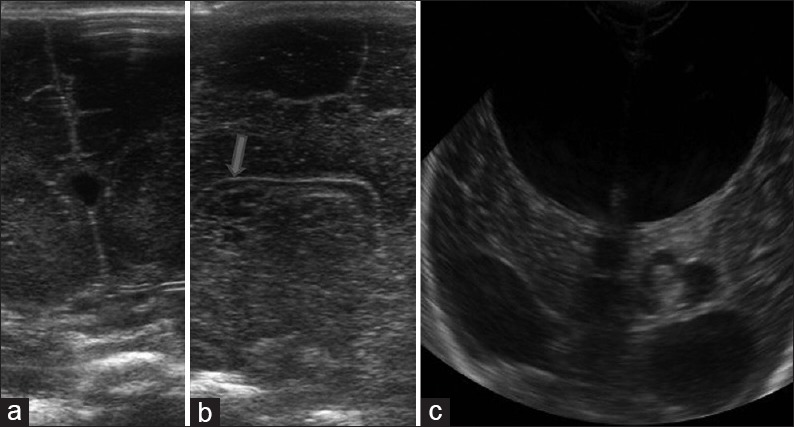

Figure 4.

Variants (a) coronal high resolution ultrasound image demonstrates the cavum septum pellucidum seen as a midline cyst between the frontal horns of lateral ventricles. (b) Two high resolution sagittal images (both sides) shows multiple cysts parallel to the lateral ventricle suggestive of connatal cysts. (c) Coronal image reveals left choroid plexus cyst. Also noted is communicating hydrocephalus

Cavum veli interpositi

It is a potential space between the choroid in the roof of the third ventricle (below) and the columns of the fornices (above). It appear as an anechoic, inverted, pyramidal space postero-inferior to the splenium of CC, i.e., in the pineal region. It is not seen after 2 years of age.[9] Differential diagnosis includes arachnoid cyst. However, cavum veli interpositi lacks mass effect.

Frontal horn variants (cysts)

Also called coarctation of the FH and connatal cysts, these represent cysts oriented exactly parallel to the FH. Generally bilateral, these may show septations between them the FH [Figure 4b].

Choroid plexus variants

Normal choroid plexus occurs in the roof of the third ventricle and extends into LVs.

There is no extension past the caudothalamic grooves, i.e., the FH and occipital horns have no choroid plexus and echogenic material in these sites suggests intraventricular hemorrhage.

Choroid plexus demonstrates considerable variations in the shape: Lobular or bulbous variants frequently occur within the ventricular atria and LVs. Small choroid cysts are a common finding at neonatal autopsy [Figure 4c]. These small cysts are of no clinical significance; however, larger cysts have been described.[10]

Hyperechoic white matter pseudolesion or periventricular halo

Already mentioned in the section on techniques of imaging, these are apparent periventricular echogenic areas that are noted only in one plane of imaging. These artifacts are due to anisotropic effect. As a general rule, pathologic abnormality on cranial ultrasound should be noted in two planes.[6]

Lenticulostriate vasculopathy

It represents a nonspecific finding seen on sonography as unilateral or bilateral branching, punctate or linear, echogenicity within the thalami [Figure 5]. Pathologically there is thickening of the arterial walls secondary to a variety of pathologic conditions, including congenital infections such as TORCH, metabolic disorders and chromosomal abnormalities.[11] In many cases, no underlying association is found.

Figure 5.

Lenticulostriate vasculopathy. Sagittal image shows branching linear echogenicities in the location of thalamus suggestive of lenticulostriate vasculopathy

Pathology

Hypoxia and hemorrhage

Neonatal hypoxic lesions and intracranial hemorrhagic lesions are classified into those that occur in preterm term infants and term neonates. In the former group, these lesions are GMH, intraventricular hemorrhage and PVL.[12] In term infant, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and intracranial hemorrhage are the major manifestations. Sonography is highly accurate in detecting hemorrhage as well as for showing the resulting ventricular dilatation. Similarly, it is the technique of choice in the screening and follow-up of premature neonates for PVL. Multiple sequential examinations are necessary and sonography is ideal in this context.

PVL represents an ischemic injury involving the watershed area of the preterm brain, i.e., the periventricular white matter. There is no accurate way to diagnose PVL in the acute phase. Sonography is the best available imaging modality though it also remains fairly insensitive in early cases. Findings include focal areas of increased echogenicity in the superolateral periventricular areas, most prominent at the level of the atria [Figure 6a]. Pitfall already mentioned in this context is the normal periventricular flare due to anisotropic effect. Mild cases of PVL can resolve on follow-up sonography. Chronic PVL results in ventriculomegaly, periventricular cystic change, and loss of deep white matter, with the sulci approximating the ventricular wall [Figure 6b]. MRI has a better sensitivity and specificity in chronic PVL.

Figure 6.

Periventricular leukomalacia. (a) Coronal image shows marked periventricular echogenities in bilateral parietal location, finding suggestive of periventricular leukomalacia. (b) Multiple cystic lesions in the periventricular location are seen on coronal image as a manifestation of cystic periventricular leukomalacia

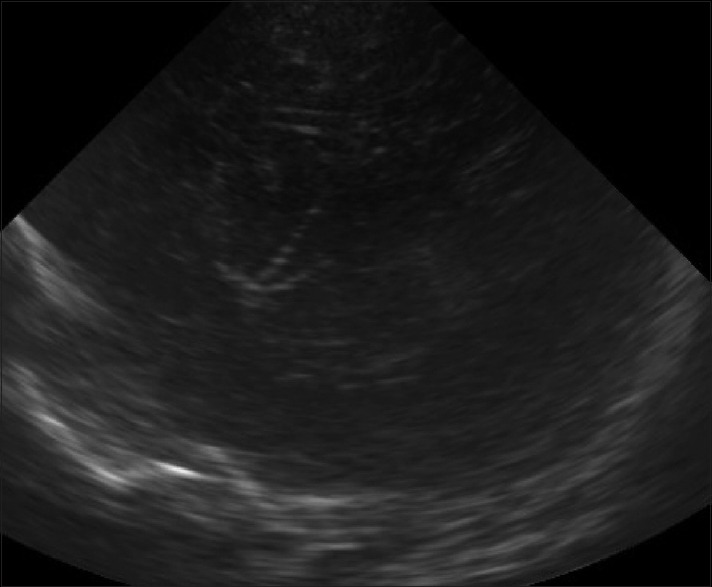

Hypoxic/ischemic injury in the term neonate results in focal or diffuse brain injury, depending upon the severity of the insult. In diffuse hypoxic/ischemic injury, sonography shows brain swelling with slit like ventricles and loss of visualization of the normal sulci with abnormally increased brain parenchymal echogenicity [Figure 7]. Areas predisposed for focal injury are basal ganglia, thalami, perirolandic cortex [Figure 8].

Figure 7.

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Coronal image demonstrates diffuse hypoxic brain injury as bilaterally symmetric echogenicity with loss of gray-white matter differentiation suggestive of brain edema. CC: Cerebral hemisphere, C: Cerebellum, CP: Choroid plexus; LV: Lateral ventricle

Figure 8.

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Coronal high resolution images show focal hypoxic injury as increased echogenicity of bilateral thalami (arrows)

Most common site of hemorrhage in preterm neonates is a germinal matrix.[13] This is noted as echogenic areas in the caudothalamic groove [Figure 9a]. The hemorrhage can extend into the ventricles [Figure 9b] or into the parenchyma [Figure 9c], former resulting in hydrocephalus.

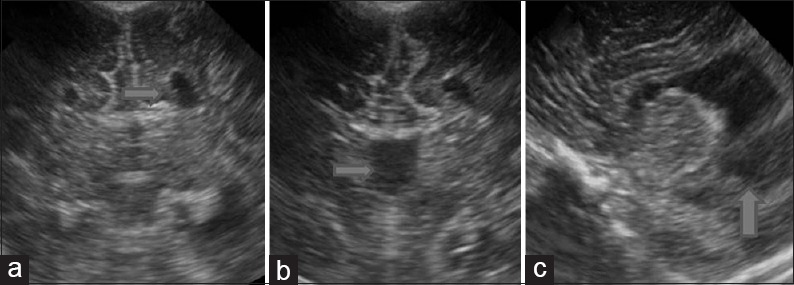

Figure 9.

Intracranial hemorrhage (a) sagittal image shows the typical appearance of germinal matrix hemorrhage as echogenic focus in the caudo-thalamic groove. C: Caudate; TH: Thalamus. (b) Intraventricular hemorrhage is seen on this coronal image as echogenic contents within the frontal horn with layering (arrows). (c) Coronal image demonstrates bilateral temporoparietal echogenic lesions (arrows) suggestive of intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Also note mild mid-line shift towards left side

Congenital anomalies

Congenital malformations of brain are relatively common. Antenatal sonography allows diagnosis of several of these malformations, however, when such malformations are suspected at birth, sonography plays a crucial role. Several malformations detected at sonography include as hydrocephalus secondary to aqueductal stenosis, Chiari II malformation [Figure 10]; posterior fossa cystic abnormalities including Dandy-Walker spectrum [Figure 11a]; holoprosencephaly [Figure 11b]; schizencephaly; agenesis of the CC [Figure 12]; vein of Galen malformation and arachnoid cysts. A normal cranial sonography excludes these malformations, avoiding further work up. However, MRI is essential to characterize complex anomalies such as polymicrogyria, heterotopia, etc.[14]

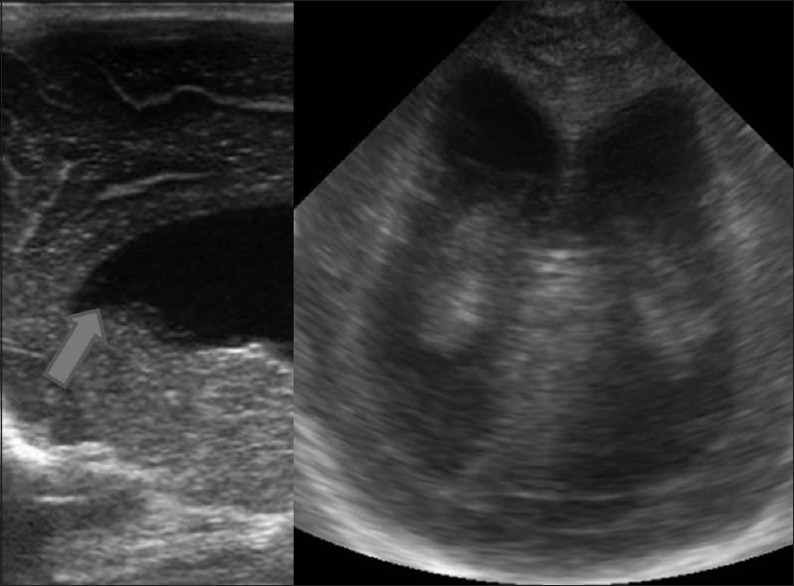

Figure 10.

Arnold Chiari malformation Type II. Sagittal and coronal images in a neonate with myelomeningocele shows hydrocephalus with colpocephaly and beaking of the frontal horn (arrow) typical of Arnold Chiari II malformation

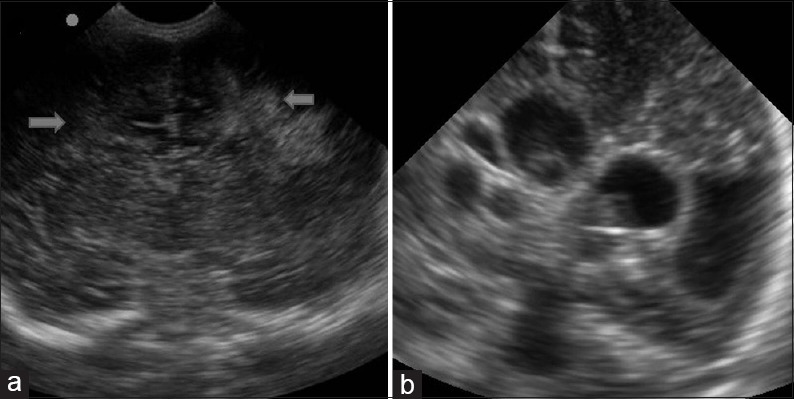

Figure 11.

Congenital malformations (a) coronal image through the posterior fossa reveals a cystic lesion occupying posterior fossa with dilatation of bilateral lateral ventricles suggestive of Dandy walker malformation. (b) Coronal image demonstrates a single holoventricle with absence of bilateral basal ganglia and thalami. The midline structure (arrow) is the fused massa intermedia. These findings are suggestive of alobar holoprosencepahly

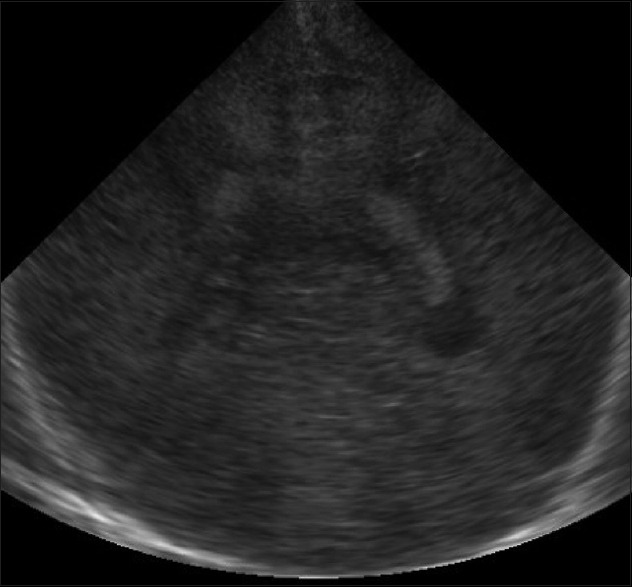

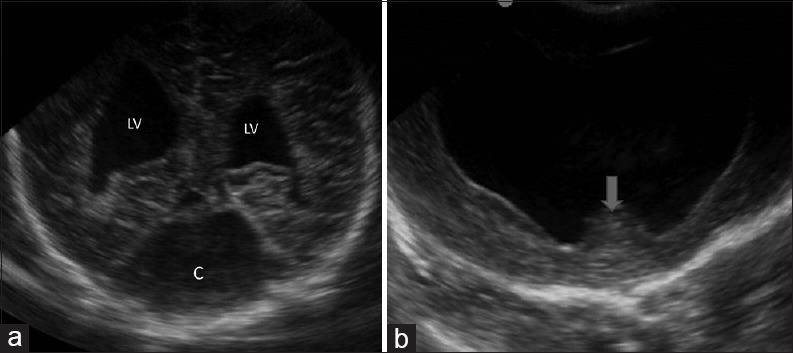

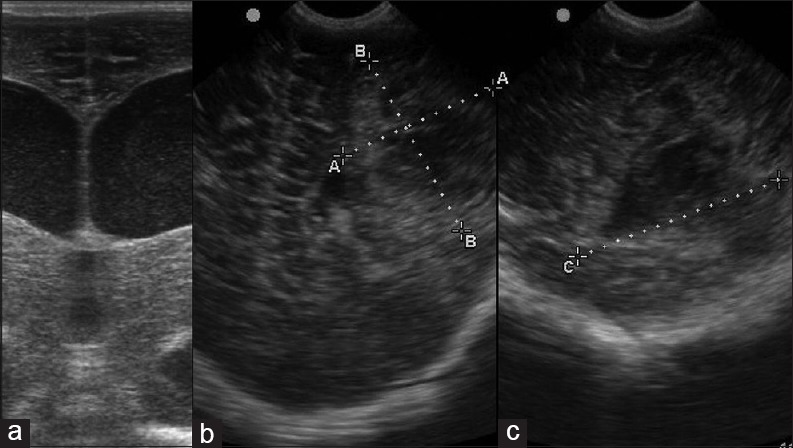

Figure 12.

Corpus callosum agenesis. Coronal (a and b) and sagittal images (c) demonstrate findings in a case of corpus callosum agenesis). Medial indentation of bilateral frontal horns caused by Probst bundles (a, arrow), absence of septum pellucidum (b, arrow) and colpocephaly (c, arrow) are all typical of corpus callosum agenesis

Infections

In-utero infections during the first two trimesters result in congenital malformations while those occurring in the third trimester cause destructive lesions. Findings in congenital TORCH infection include microcephaly, calcifications in the periventricular region [Figure 13], brain atrophy, hydrocephalus, subependymal cysts, and lenticulostriate vasculopathy.

Figure 13.

Congenital infection. Coronal image shows a hyperechoic focus in the left periventricular location in a child with microcephaly, suggestive of TORCH infection

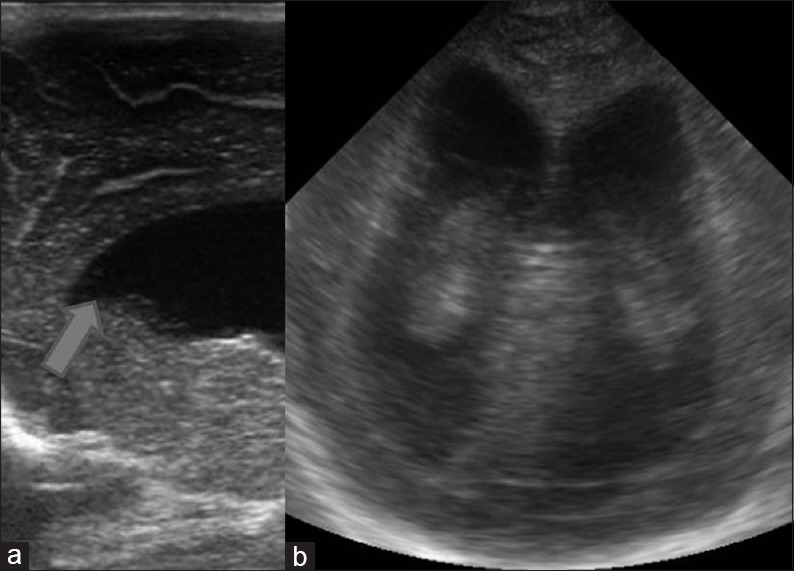

Neonatal CNS infections are diagnosed based on clinical presentation, and the role of sonography is to diagnose complications such as subdural fluid collections, ventriculitis [Figure 14a], cerebritis, abscess [Figure 14b and c], infarction, and hydrocephalus.[15]

Figure 14.

Acquired infection (a) high resolution coronal image in a newborn with high grade fever demonstrates dilatation of both lateral ventricles with echogenic debris within suggestive of ventriculitis. (b and c) Coronal and sagittal images in an infant with high grade fever and right hemiparesis reveals a heteroechoic lesion in the left parietal cortex suggestive of abscess. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (not shown) confirmed the findings

Tumors

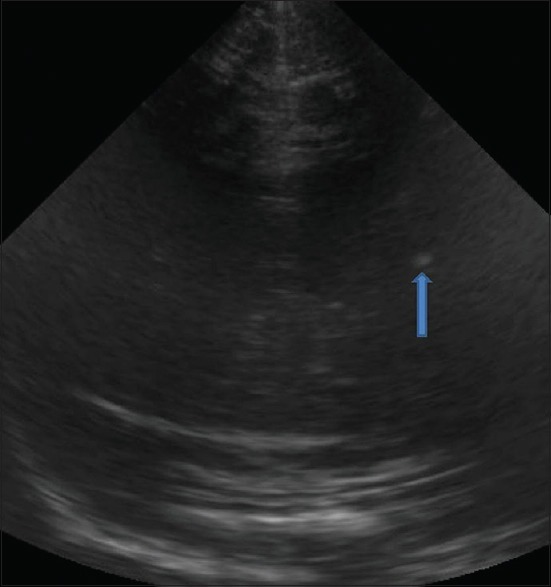

Intracranial neoplasms are rare in neonates and infants. If such suspicion does arise, MRI and computed tomography are the preferred imaging techniques. Sometimes, intracranial tumor are detected in infants are being examined for other symptoms and signs such as a large head [Figure 15].

Figure 15.

Tumor. Sagittal image shows a lobulated echogenic mass in the third ventricle (arrow) with hydrocephalus (short arrow). Histopathology of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of choroid plexus papilloma

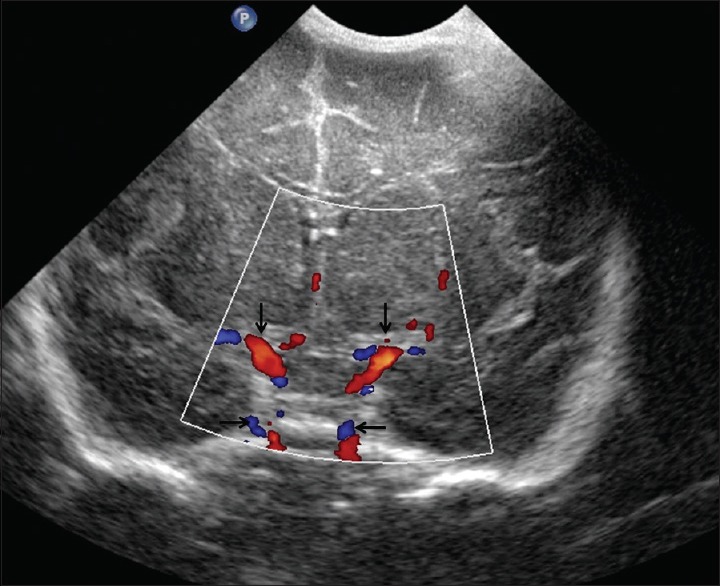

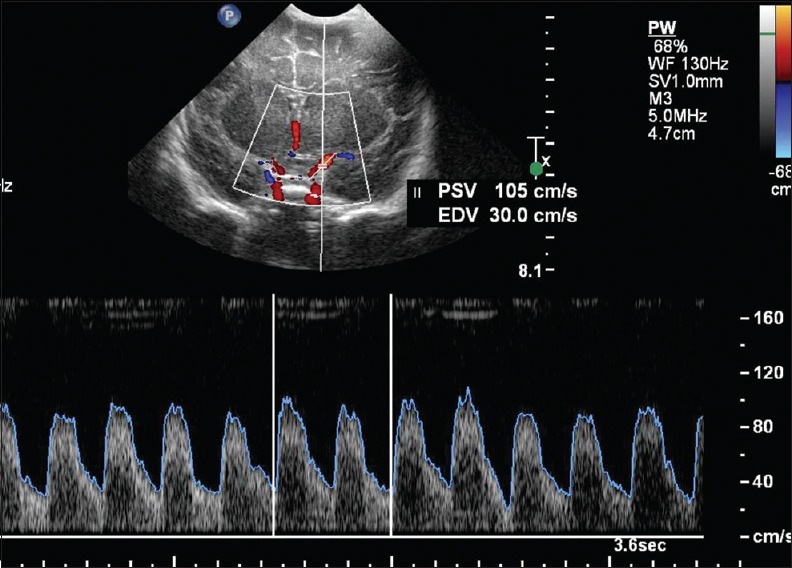

Role of Transfontanelle Doppler

The anterior fontanelle approach is the most commonly utilized approach for Doppler evaluation. Vascular structures routinely visualized on sagittal scan include the basilar, internal carotid, and anterior cerebral arteries, as well as the internal cerebral veins, vein of Galen, and the superior sagittal and straight sinus [Figures 16 and 17]. Coronal scans allow evaluation of the supraclinoid internal carotid arteries, M1 segments of the MCAs, thalamostriate arteries, A1 segments of the anterior cerebral arteries, and the cavernous sinus [Figures 18 and 19]. The temporal bone approach is best for the MCA because it is parallel to flow. The resistive index of major intracranial arteries ranges from 0.6 to 0.8.[16] Doppler plays an important role in diagnosis and follow-up of brain damage secondary to ischemia, hemorrhage, infection, developmental disorder, and tumors [Figure 15]. Besides, it is used for differentiation of a subarachnoid from subdural fluid collections and diagnosis of venous thrombosis.

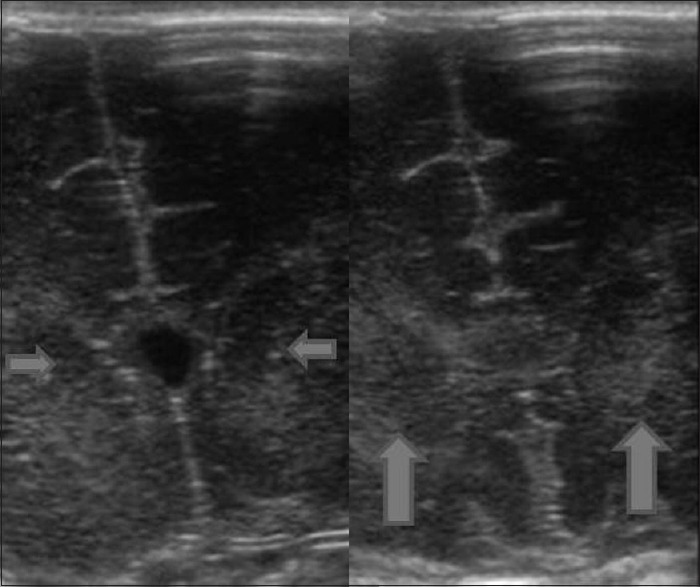

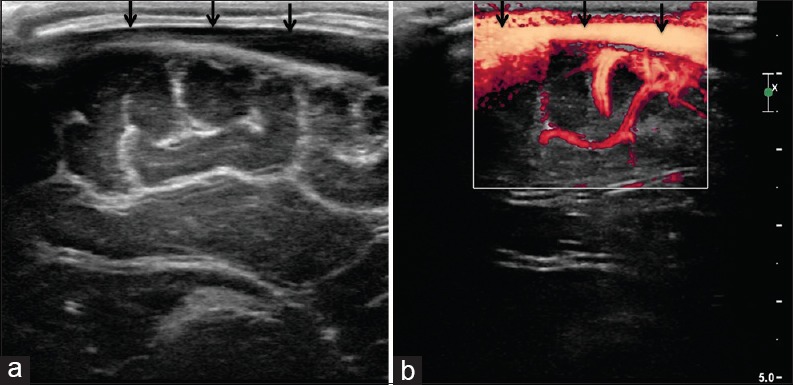

Figure 16.

(a and b) Superior sagittal sinus. Sagittal view through the anterior fontanelle shows normal appearance of the superior sagittal sinus (arrows)

Figure 17.

(a and b) Superior sagittal sinus. Coronal view through the anterior fontanelle shows normal appearance of the superior sagittal sinus (arrows)

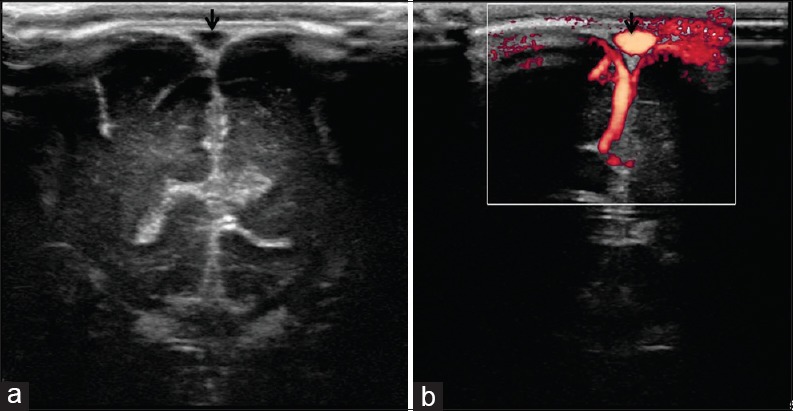

Figure 18.

Circle of Willis. Coronal view through the anterior fontanelle shows normal circle of Willis (arrows)

Figure 19.

Doppler evaluation of middle cerebral arteries. Coronal view through the anterior fontanelle shows normal waveform of the left middle cerebral arteries

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rumack C, Wilson S, Charboneau W, editors. Diagnostic Ultrasound. 2nd ed. Ch. 53. Vol. 2. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1997. Neonatal and infant brain imaging; pp. 1443–502. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock DS. Sonography of the brain in infants: Role in evaluating neurologic abnormalities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:417–23. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.2.7618570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epelman M, Daneman A, Kellenberger CJ, Aziz A, Konen O, Moineddin R, et al. Neonatal encephalopathy: A prospective comparison of head US and MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1640–50. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1634-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowe LH, Bailey Z. State-of-the-art cranial sonography: Part 1, modern techniques and image interpretation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1028–33. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seigel M, editor. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. Pediatric Sonography. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant EG, Schellinger D, Richardson JD, Coffey ML, Smirniotopoulous JG. Echogenic periventricular halo: Normal sonographic finding or neonatal cerebral hemorrhage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;140:793–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.140.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.North K, Lowe L. Modern head ultrasound: Normal anatomy, variants, and pitfalls that may simulate disease. Ultrasound Clin. 2009;4:497–512. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farruggia S, Babcock DS. The cavum septi pellucidi: Its appearance and incidence with cranial ultrasonography in infancy. Radiology. 1981;139:147–50. doi: 10.1148/radiology.139.1.7208915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CY, Chen FH, Lee CC, Lee KW, Hsiao HS. Sonographic characteristics of the cavum velum interpositum. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1631–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta JK, Cave M, Lilford RJ, Farrell TA, Irving HC, Mason G, et al. Clinical significance of fetal choroid plexus cysts. Lancet. 1995;346:724–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teele RL, Hernanz-Schulman M, Sotrel A. Echogenic vasculature in the basal ganglia of neonates: A sonographic sign of vasculopathy. Radiology. 1988;169:423–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.2.2845473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergani P, Locatelli A, Doria V, Assi F, Paterlini G, Pezzullo JC, et al. Intraventricular hemorrhage and periventricular leucomalacia in preterm infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:225–31. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000130838.02410.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burstein J, Papile LA, Burstein R. Intraventricular hemorrhage and hydrocephalus in premature newborns: A prospective study with CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132:631–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.132.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barkovich AJ. New York: Raven; 1990. Pediatric Neuroimaging. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank JL. Sonography of intracranial infection in infants and children. Neuroradiology. 1986;28:440–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00344098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allison JW, Faddis LA, Kinder DL, Roberson PK, Glasier CM, Seibert JJ. Intracranial resistive index (RI) values in normal term infant during the first day of life. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:618–620. doi: 10.1007/s002470000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]