Abstract

Tuberculous myelitis usually involves thoracic and only rarely, distal cord. Longitudinal lesions more than three spinal segments long in tuberculosis (TB) are usually due to intramedullary tuberculomas and not infectious myelitis. We report a 17-year-old male with acute myelitis from D7 to conus medullaris, diffuse spinal meningitis, subdural and epidural abscesses, normal vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and brain imaging. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed raised proteins, lymphocytosis, hypoglycorrhagia, and positive TB-polymerase chain reaction. Chest X-ray was normal, and sputum was negative for acid-fast Bacilli. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed endobronchial TB. The patient was successfully treated with antitubercular drugs and steroids. In endemic areas, a high index of suspicion should be kept for TB in patients with myelitis, especially those with spinal abscesses and a suggestive CSF report. In selected cases, there may be a role of CT scan inspite of normal X-ray.

Keywords: Distal myelitis, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, tuberculosis

Introduction

Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) is commonly seen due to demyelinating lesions such as viral or postviral demyelination or neuromyelitis optica (NMO).[1] In up to 12% of patients with idiopathic myelitis, the location is lumbar.[2] Later, lumbar myelitis is a feature of antimyelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein syndrome.[3] Tuberculosis (TB) usually causes cervicodorsal focal myelitis, whereas long lesions in the spinal cord are more commonly due to tuberculomas and abscesses, rather than myelitis. Among patients of HIV-TB coinfection, 30% had myelitis/arachnoiditis, and the most common cause of myelopathy/cauda equina in HIV patients was TB.[4] We present one such case of infective distally LETM due to TB unrelated to HIV.

Case Report

A 17-year-old Indian man presented with a 1-month history of low-grade fever with anorexia followed by a 5-day history of acute sensorimotor paraparesis. There was no preceding or concurrent history of any gastroenteritis or other illness. There was no past history of any previous similar illness. The patient was well-built and nourished. Both legs had three-fifth power, absent of tendon reflexes and anesthesia below D9 spinal level. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a multi-segment confluent patchy nonmass-like granulomatous central intramedullary T1-weighted isointense and T2-weighted hyperintense signal abnormality from D7 to conus medullaris without cord expansion suggestive of granulomatous myelitis [Figure 1]. There was a marked postgadolinium enhancement on cord surface, extramedullary epidural and subdural abscesses along the cervical and dorsal cord, abnormal clumping, and contrast enhancement of cauda equina roots [Figure 2]. Vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and brain MRI were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a normal opening pressure, with 230 cells/cumm (98% lymphocytes), 236 mg/dL proteins, and glucose 27 mg/dL (matching serum glucose 92 mg/dL). Antinuclear antibody and antiaquaporin-4 antibodies (AQP4-IgG) (by indirect immunofluorescence using transfected HEK2 cells and primate optic nerve as substrate) were negative, and acetylcholine esterase level was normal. Mycobacterium TB-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in CSF was positive. HIV-ELISA was negative. The patient was neither immunosuppressed due to any illness nor was there any history of iatrogenic immunosuppression by any drugs. His chest X-ray (CXR) was normal [Figure 3], and sputum was negative for acid-fast Bacilli. Chest and abdomen computed tomography (CT) showed three soft tissue nodules in the right upper lobe, one in the right lower lobe and multiple peribronchial nodules, some with central cavitation and a 3 cm × 3.5 cm necrotic subcarinal lymph node [Figure 4]. CT was thus suggestive of endobronchial TB with tuberculous lymphadenitis. The patient did not consent for a bronchoscopic lymph node biopsy. Thus, a final diagnosis of tuberculous longitudinally extensive myeloradiculopathy was made. The patient was given dexamethasone in tapering dose with 4-drug antitubercular therapy (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) for 2 months, followed by isoniazid and rifampicin for 10 more months. Our patient was ambulatory without support within 2 weeks of treatment initiation and attained full power by the 5th week. He continues to be under our follow-up since last 18 months with no residual deficits. The patient refused for a repeat MRI scan due to severe claustrophobia in the first imaging and as he had improved.

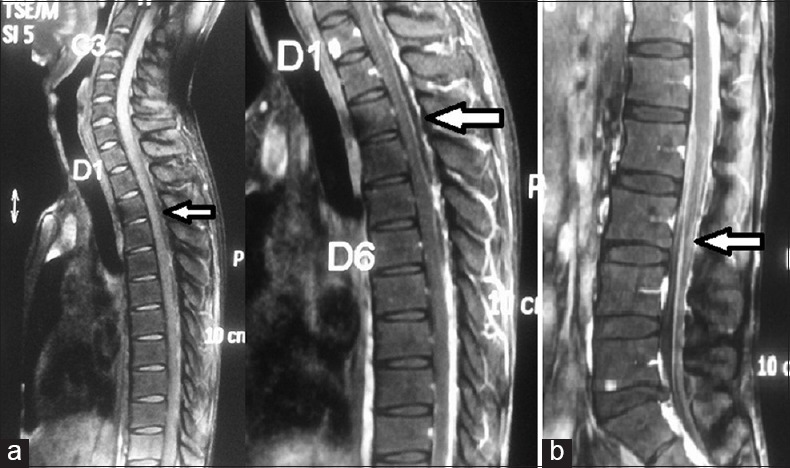

Figure 1.

(a) Saggital magnetic resonance imaging image showing T2-weighted hyperintense signals in spinal cord below D7 vertebral level; (b) axial images hyperintense signals in central spinal cord at D7-8 level (white arrows)

Figure 2.

(a) Postgadolinium saggital magnetic resonance imaging images showing epidural and subdural fluid collections suggestive of abscesses and marked enhancement of cord surface from D7 to conus medullaris; (b) abnormal clumping and contrast enhancement of cauda equina roots on postgadolinium magnetic resonance imaging (white arrows)

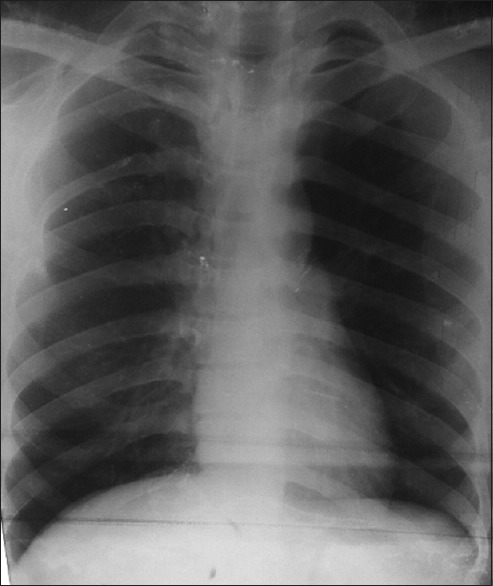

Figure 3.

X-ray chest postero-anterior view showing no evidence of tuberculosis

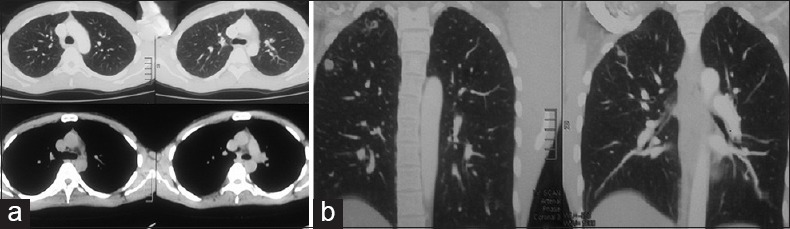

Figure 4.

(a and b) Computed tomography chest axial and coronal images showing tuberculous lesions

Discussion

TB is a global disease which potentially affects almost the entire neuraxis from the brain to the nerves.[5] During the stage of bacteremia of the primary tuberculous infection or shortly afterward, a small tuberculous (Rich's) focus develops in the meninges, subpial, or subependymal surface of the brain or spinal cord and may remain dormant for years. Immunological factors lead to rupture of these lesions and subsequent dissemination in the ventricular system. The acute form presents with fever, headache, and radiating root pains, accompanied by myelopathy. On the other, the chronic form presents with progressive spinal cord compression and may suggest a spinal cord tumor. The characteristic MRI features include CSF loculation and obliteration of the spinal subarachnoid space with loss of outline of the spinal cord in the cervicothoracic region and matting of nerve roots in the lumbar region.[5] Less than half of tuberculous myelitis patients have pulmonary symptoms, and most common cause of myelopathy is vertebral body disease or Pott's spine.[5] TB less commonly leads to intramedullary or intradural extramedullary tuberculomas, granulomatous myeloradiculitis, spinal artery vasculitis with cord infarct, or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.[5] Tuberculous myelitis is most common in the cervicothoracic spinal cord, and only one patient of tuberculous distal myelitis has been reported till date.[6] One report mentions tuberculous abscesses to be common in the conus region.[7] In addition, most reported cases have associated brain lesions or cerebral leptomeningitis. Our patient with normal vertebrae and brain MRI had longitudinally extensive confluent central cord-predominant myelitis from the distal thoracic cord to conus medullaris with diffuse spinal meningitis, and epidural and subdural abscesses is uncommon. In the most common primary central nervous autoimmune disease (Multiple Sclerosis [MS]), myelitis lesions are predominantly posterolateral and confluent (as sometimes seen in MS) and in NMO spectrum disorders (NMOSD) the lesions are contiguous, central area of the medulla is involved, contrast enhancement is patchy and inhomogeneous, spinal “bright spotty lesions” are seen.[1] It is important to test for AQP4-IgG in patients with LETM to exclude a coincidence of AQP4-IgG-positive NMO with TB as previously reported in many recent cases, as both can cause a confluent, central cord, contrast enhancing myelitis. One way to differentiate is the associated subdural and/or epidural abscesses as also vertebral/disc disease seen in TB, unlike other NMOSD. Although previous reports mention a correlation between TB and NMO, a recent report failed to find a significant correlation.[8,9]

Thus, it may be difficult to distinguish between tuberculous myelitis and idiopathic LETM or NMOSD. If CSF shows raised cells and significantly raised proteins, and MRI shows vertebral/disc disease or associated spinal abscesses, then CSF TB-PCR and CXR should be done. In central nervous system TB, conventional single-step PCR have a low sensitivity (overall 56%, as low as 22%) inspite of a high specificity (98%), though newer nested PCR techniques have sensitivities up to 100%.[10] Thus, treatment decisions should not rely solely on TB-PCR. In addition, as in our patient, CXR may be completely normal and thus chest CT scan may be done in appropriate clinical settings. In addition, in selected steroid-resistant cases, a trial of antitubercular drugs might be considered, especially in endemic areas with poor laboratory support. The response of TB myelitis may be favorable if treatment is initiated early and before irreversible complications such as cord atrophy or syrinx formations occur.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Kirti Rana, Department of Radiology, Dr. S. N. Medical College, Jodhpur.

References

- 1.Jarius S, Wildemann B, Paul F. Neuromyelitis optica: Clinical features, immunopathogenesis and treatment. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;176:149–64. doi: 10.1111/cei.12271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobo Calvo A, Mañé Martínez MA, Alentorn-Palau A, Bruna Escuer J, Romero Pinel L, Martínez-Yélamos S. Idiopathic acute transverse myelitis: Outcome and conversion to multiple sclerosis in a large series. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato DK, Callegaro D, Lana-Peixoto MA, Waters PJ, de Haidar Jorge FM, Takahashi T, et al. Distinction between MOG antibody-positive and AQP4 antibody-positive NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2014;82:474–81. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Candy S, Chang G, Andronikou S. Acute myelopathy or cauda equina syndrome in HIV-positive adults in a tuberculosis endemic setting: MRI, clinical, and pathologic findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1634–41. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho TA, Vaitkevicius H. Infectious myelopathies. Continuum Lifelong Learn Neurol. 2012;18:1351–73. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000423851.63017.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasay M, Arif H, Khealani B, Ahsan H. Neuroimaging of tuberculous myelitis: Analysis of ten cases and review of literature. J Neuroimaging. 2006;16:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2006.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy KJ, Brunberg JA, Quint DJ, Kazanjian PH. Spinal cord infection: Myelitis and abscess formation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:341–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zatjirua V, Butler J, Carr J, Henning F. Neuromyelitis optica and pulmonary tuberculosis: A case-control study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1675–80. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li R, Zhong X, Qiu W, Wu A, Dai Y, Lu Z, et al. Association between neuromyelitis optica and tuberculosis in a Chinese population. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi T, Tamura M, Takasu T. The PCR-based diagnosis of central nervous system tuberculosis: Up to date. Tuberc Res Treat 2012. 2012:831292. doi: 10.1155/2012/831292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]