Abstract

Purpose

Treatment for rectal and anal cancer (RACa) can result in persistent bowel and gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction. Body image problems may develop over time and exacerbate symptom-related distress. RACa survivors are an understudied group, however, and factors contributing to post-treatment well-being are not well understood. This study examined whether poorer body image explained the relation between symptom severity and psychological distress.

Methods

Participants (N=70) completed the baseline assessment of a sexual health intervention study. Bootstrap methods tested body image as a mediator between bowel and GI symptom severity and two indicators of psychological distress (depressive and anxiety symptoms), controlling for relevant covariates. Measures included the EORTC-QLQ-CR38 Diarrhea, GI Symptoms, and Body Image subscales and Brief Symptom Index Depression and Anxiety subscales.

Results

Women averaged 55 years old (SD=11.6), White (79%), and 4-years post-treatment. Greater Depression related to poorer body image (r=−.61) and worse diarrhea (r=.35) and GI symptoms (r=.48). Greater Anxiety related to poorer body image (r=−.42) and worse GI symptoms (r=.45), but not diarrhea (r=.20). Body image mediated the effects of bowel and GI symptoms on Depression, but not on Anxiety.

Conclusions

Long-term bowel and GI dysfunction are distressing and affect how women perceive and relate to their bodies, exacerbating survivorship difficulties. Interventions to improve adjustment post-treatment should address treatment side effects, but also target body image problems to alleviate depressive symptoms. Reducing anxiety may require other strategies. Body image may be a key modifiable factor to improve well-being in this understudied population. Longitudinal research is needed to confirm findings.

Keywords: rectal cancer, anal cancer, psychological distress, body image, bowel dysfunction, gastrointestinal symptoms

Treatment for rectal and anal cancer often includes radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery, alone or in combination, and may include a temporary or permanent stoma. These treatments often result in adverse side effects including bowel and gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction that can last for years post-treatment [1, 2]. Negative psychological reactions to unpleasant changes in body functioning and appearance may exacerbate these difficulties [3]. Given the prevalence and persistence of bowel and GI dysfunction post-treatment and quality of life implications, identifying modifiable factors that alleviate distress is an important survivorship concern.

Following treatment for rectal and anal cancer, prevalence estimates for bowel and GI dysfunction range from 13–49% for diarrhea and 7–16% for GI symptoms [add refs 4–7] [8, 9], which may persist for years into survivorship [10, 11]. Survivors coping with bowel and GI symptoms report disruptions in daily routines and social activities, sexual dysfunction, and reduced emotion well being and quality of life [5, 12–14]. Although research in rectal and anal cancer is limited, greater severity of bowel and GI symptoms increases the likelihood of anxiety and depression in colorectal patients [15, 16]. Medical interventions typically include medication and diet alterations and have mixed results. Identifying modifiable factors that exacerbate symptom-related distress is warranted.

Given unpleasant, disruptive, and potentially distressing side effects, problems with body image may develop. Problems with body image may refer to dissatisfaction with body functioning or appearance and can have a profound affect on identity and self-concept, particularly for women [17, 18] Both rectal and anal cancer survivors report significant body image concerns [2, 19–21]. Bowel and GI dysfunction appear to be related to reported body image difficulties [22][23]. The ways in which survivors view and accept their bodies while experiencing unwanted body changes may be one mechanism by which treatment side effects influence psychological well-being in survivorship. For women, in particular, changes in body image may have more generalized effects on psychosocial well-being [3].

The available literature on rectal and anal cancer survivorship has primarily used descriptive statistics to characterize quality of life domains and the co-occurrence of treatment side effects. There has been little evaluation of how treatment side effects may relate to body image problems and potential implications for more general measures of psychological distress. Among colorectal cancer survivors, disturbances in body image have been associated with higher levels of post-treatment distress, depression, and anxiety [24, 26, 27]. Prospective studies in other cancers corroborate these relations indicating that body image may precede psychosocial difficulties [3]. The unique experiences of rectal and anal cancer survivors are not well understood, however, and little is known about what factors may lead to greater psychological distress for this specific group.

Present Study

This study aimed to evaluate the degree to which bowel and GI dysfunction related to psychological distress in women who completed treatment for rectal or anal cancer. We also examined whether body image mediated the effect of bowel and GI dysfunction on psychological distress. Specifically, we tested whether relations varied based on using depressive versus anxiety symptoms as indicators of psychological distress. We hypothesized that poorer body image, as a result of persistent bowel and GI symptoms, would be related to increased depressive and anxiety symptoms. Determining which aspects of psychological distress may be alleviated by targeting body image problems can be used to inform the development of intervention techniques to improve coping and quality of life in post-treatment survivorship.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N=70) were part of a sexual health intervention study for women reporting low to moderate satisfaction with their sexual functioning and overall sexual life (see Philip and colleagues [28] for full study information). Sexual satisfaction was assessed using an item from the Female Sexual Function Index (“Over the past 4 weeks, how satisfied have you been with your overall sexual life?”; 5=Very Satisfied to 1=Very Dissatisfied) and individuals scoring a 5 were excluded [29]. Inclusion criteria included being post-treatment (post-radiation and/or surgery for stage I-III rectal adenocarcinoma or rectosigmoid cancer with an anastomosis at 15 cm or below; post-radiation and/or chemotherapy for anal cancer) with no evidence of disease, at least 21 years old, and proficient in English. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All study materials and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Data from the baseline assessment (pre-intervention) was used.

Measures

Socio-Demographic and Medical Information

Socio-demographic information was collected using standard questionnaires. Medical and treatment data were collected via medical chart review.

Bowel and Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Body Image

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30)[30] and Colorectal Cancer-Specific Module (QLQ-CR38) assessed bowel and GI symptoms and body image.[7] The QLQ-C30 (30-items) is a well validated self-report measure of health-related quality of life in cancer patients. The QLQ-CR38 is a supplement that includes 38 additional items specific to colorectal cancer. Bowel and GI symptoms were measured using the Diarrhea single item (“Have you had diarrhea?”) and the five-item GI Symptoms subscale (e.g., feeling bloated, gas, and pain in abdomen). Body Image was measured with three items that assess whether respondents feel physically less attractive, less feminine, and/or dissatisfied with their bodies as a result of cancer treatment. All items are rated on a four-point Likert scale (“Not at All” to “Very Much”). Scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms and better body image.

Psychological Distress

Depressive and anxiety symptoms were selected as two indices of psychological distress and measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)[31] Depression and Anxiety subscales, respectively. Each subscale includes six items that ask respondents to rate how much discomfort problems have caused them in the past month on a five-point Likert scale (“Not at all” to “Extremely”). Individual scores for the items on each subscale were averaged. Scores range from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Both the Depression and Anxiety subscales demonstrated good internal consistency reliability in this sample (Cronbach’s alphas, .77 and .87, respectively).

Statistical Analysis

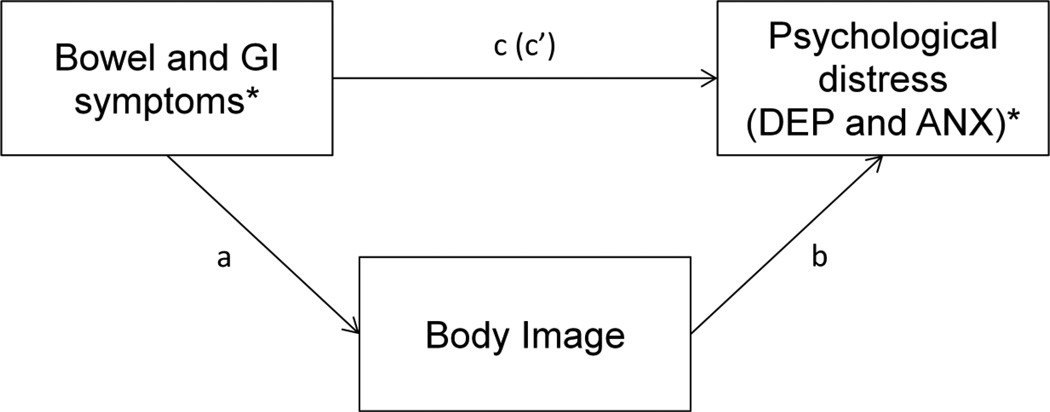

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations were performed for all study variables. Independent sample t-tests examined differences between women with and without a stoma. The role of body image mediating the effect of bowel and GI symptoms on psychological distress was tested with four models that specified Diarrhea and GI Symptoms as predictors, Body Image as a mediator, and Depression and Anxiety as outcome variables (Figure 1). Each model provided estimates and confidence intervals around the indirect (mediating) effects of the predictors on the outcomes through the mediator. Traditional tests of mediation require assumptions of normality that may be violated with smaller samples. Therefore, bootstrap methods were used to obtain nonparametric estimates of sampling distributions of the indirect effects [32], which maximizes statistical power [33]. The indirect effect was regarded significant if a zero was not included in the confidence interval of the estimate, indicating that Body Image mediated the relation between the predictor and the outcome. Bootstrap analysis was conducted in SPSS v. 22 with Hayes (2012) PROCESS Macro [34]. Based on standard recommendations, the bootstrapped mediated effects (BMED) and 95% bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) confidence intervals for indirect effects were obtained from 5,000 bootstrapped samples [32].

Figure 1.

Four mediation models were tested including bowel and GI symptoms as predictors, depressive and anxiety symptoms as outcomes, and body image as a mediator. DEP = depressive symptoms; ANX = anxiety symptoms; a = direct effect of bowel or GI symptoms on body image; b = direct effect of body image on depressive or anxiety symptoms; c = unmediated path from bowel or GI symptoms to depressive or anxiety symptoms (total effect); c’ = direct effect from bowel or GI symptoms to depressive or anxiety symptoms accounting for the mediated effect of body image.

*Tested in separate models.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 present descriptive data. Participants were a convenience sample of mostly rectal cancer survivors (71%), averaged 4.3 years (SD=3.3, median=4) post-treatments, and had undergone multimodal treatments (73% had surgery; 71% underwent radiation/chemotherapy combined). Ten participants (14%) had a permanent stoma.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N = 70)

| Demographic Information | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.4 | 11.6 |

| Time since treatment (years) | 4.3 | 3.3 |

| n | % | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 5 | 8 |

| Not Hispanic | 56 | 92 |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 | 1 |

| Asian | 3 | 1 |

| Black or African American | 6 | 59 |

| White | 55 | 33 |

| Other | 2 | 2 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 11 | 16 |

| Married | 40 | 57 |

| Separated | 3 | 4 |

| Divorced | 11 | 16 |

| Widowed | 5 | 7 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Unemployed | 11 | 16 |

| Homemaker | 6 | 9 |

| Employed, Full- or Part-time | 33 | 49 |

| Retired | 14 | 21 |

| Other | 4 | 6 |

| Education Level | ||

| Less than High School | 2 | 33 |

| High School Degree | 5 | 8 |

| Some College | 15 | 24 |

| College Degree | 16 | 26 |

| Some Graduate School | 24 | 39 |

| Income Status | ||

| Less than $50,000 | 17 | 31 |

| More than $50,000 | 38 | 69 |

| Type of Health Insurance | ||

| MediCARE | 11 | 16 |

| MedicAID | 2 | 3 |

| Private/Commercial | 43 | 61 |

| No insurance/Self-pay | 1 | 1 |

| Medical Information | n | % |

| Cancer Type | ||

| Rectal cancer | 48 | 69 |

| Anal cancer | 20 | 29 |

| Presurgical Stage | ||

| 1 | 22 | 31 |

| 2 | 10 | 14 |

| 3 | 29 | 41 |

| Treatment Neoadjuvant/Adjuvant | ||

| Radiation only | 1 | 1 |

| Chemotherapy only | 8 | 11 |

| Radiation/Chemotherapy | 50 | 71 |

| Surgery | ||

| Surgical treatment | 51 | 73 |

| Permanent stoma | 10 | 14 |

| Treatment Side Effects1 | n | % |

| Diarrhea | 26 | 37 |

| Feeling bloated | 24 | 34 |

| Abdominal pain | 25 | 35 |

| Pain in buttocks | 16 | 23 |

| Bothered by gas | 51 | 73 |

| Belching | 32 | 46 |

Measured using the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-C38; refers to participants who reported experiencing symptoms “A little,” “Quite a bit,” or “Very much” in the past week.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Mean (SD) | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | 20.29 (29.82) | 69 |

| Gastrointestinal Tract Symptoms | 21.45 (20.06) | 69 |

| Body Image | 69.24 (30.85) | 69 |

| Depression | 0.59 (0.69) | 70 |

| Anxiety | 0.65 (0.60) | 70 |

Note: Higher numbers indicate greater sexual satisfaction, greater severity of symptoms, better body image, and more depression/anxiety.

Thirty-seven percent of women reported diarrhea in the past week; 34% reported feeling bloated, 35% had abdominal pain, 23% reported pain in their buttocks, 73% were bothered by gas, and 46% reported belching. Sixty-one percent of women were dissatisfied with their body and 49% reported two or more body image problems. Average levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms were higher than non-patient normative levels for women [31]. Based on a validated case rule to determine “psychological distress,” 16% and 21% of participants reported clinically significant levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively (above the 90th percentile, T score ≥ 63) [31].

Survivors with a stoma reported more anxiety symptoms than survivors without a stoma (M=1.02 and 0.58, respectively; t[68]=−2.16, p=.03). No other sociodemographic variables were related to Depression or Anxiety in bivariate analysis (p’s >.10) Younger age was associated with poorer Body Image (r=.29, p=.02). Stoma patients reported poorer Body Image than non-stoma status at the trend level (t[67]= 1.71, p=.09). Table 3 presents bivariate correlations of the main variables.

Table 3.

Pearson Correlations for all Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | ||||||

| 2. Stoma Status | .077 | – | |||||

| 3. Diarrhea | −.032 | .135 | – | ||||

| 4. GI Symptoms | −.001 | .015 | .360** | – | |||

| 5. Body Image | .289* | −.204† | −.437** | −.494** | – | ||

| 6. Depressive Symptoms | −.154 | .055 | .346** | .481** | −.609** | – | |

| 7. Anxiety Symptoms | −.123 | .253* | .195 | .445** | −.421** | .646** | – |

Note: Stoma status was dichotomized for ease of interpretation: 0=not present; 1=present.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01

Mediation Analyses

Based on a priori hypotheses, four mediation models were tested (Figure 1). Direct effects evaluated relations between predictors and the mediator (path a), the mediator and the outcomes (path b), and the predictors and the outcomes (path c). As a test of mediation, indirect effects estimated the degree to which Diarrhea or GI Symptoms related to Depression or Anxiety while accounting for the mediated effect of Body Image (path c’). All models included age and presence of a permanent stoma (yes/no) as covariates (selected a priori) [3, 26].Sexual satisfaction was controlled for methodologically as an eligibility criterion with all participants reporting moderate to low satisfaction. To ensure that variability in participants’ overall sexual function was adequately controlled for, analyses were also conducted with a multidimensional measure of sexual function included as an additional covariate [29]. Given no significant difference in results, sexual function was not included in the final models. Results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Unstandardized Path Coefficients and Bootstrap Mediated Effects with Confidence Intervals for All Models

| Mediation Models | a | b | c | c’ | BMED | SE | 95% BCa LL |

95% BCa UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | ||||||||

| Diarrhea | −.432** | −.014*** | .007* | .001 | .006 | .002 | .002 | .012 |

| GI Symptoms | −.754*** | −.012*** | .016*** | .008* | .009 | .004 | .003 | .018 |

| Anxiety | ||||||||

| Diarrhea§ | −.432** | −.008** | .003 | −.001 | .003 | .0017 | .001 | .007 |

| GI Symptoms | −.754*** | −.004 | .013*** | .010** | .003 | .0022 | −.001 | .008 |

Note. The bootstrapped effect was based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. Analyses were adjusted for age and stoma status. a = path from predictor (diarrhea or GI symptoms) to body image; b = path from body image to outcome (depression or anxiety); c = unmediated path from predictor to outcome (total effect); c’ = direct effect from predictor to outcome after accounting for the mediated effect; BMED = bootstrapped mediated effect (indirect effect); SE = standard error of the bootstrapped mediated effect; BCa = bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

Percentile based 95% confident intervals are presented for this model.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Predicting Depressive Symptoms

The first mediation model tested the indirect effect of Diarrhea on Depression through Body Image. The paths from Diarrhea to Body Image (b=−.432, p<.001), from Body Image to Depression (b=−.014, p<.001), and the unmediated path, or the total effect, from Diarrhea to Depression (b=.007, p=.009) were significant. The inclusion of Body Image in the model indicated a significant indirect effect from Diarrhea to Depression through Body Image (bootstrapped mediated effect, BMED=0.006, 95% BCa CI [0.002–0.012]) with the direct effect of Diarrhea on Depression no longer significant (b=.001, p=.59), supporting mediation. Each one unit increase in reported Diarrhea resulted in a .006 increase in the predicted value of Depression through Body Image. More specifically, an increase of one standard deviation in Diarrhea (SD=29.82) was predictive of a 0.177 unit increase in Depression.

The second mediation model tested the indirect effect of GI Symptoms on Depression through Body Image. The paths from GI Symptoms to Body Image (b=−.754, p< .001), from Body Image to Depression (b=−.012, p<.001), and total effect from GI Symptoms to Depression (b=.016, p<.001) were significant. When Body Image was included in the model, the indirect effect was significant (BMED=0.009, 95% BCa CI [0.003 – 0.018]), though the direct effect of GI Symptoms on Depression also remained significant (b=.008, p=.048), suggesting Body Image was a partial mediator. An increase of one standard deviation in reported GI Symptoms (SD=20.06) was predictive of a 0.181 unit increase in Depression.

Predicting Anxiety Symptoms

To test the mediating role of Body Image between Diarrhea and Anxiety, Diarrhea was specified as the predictor, Body Image as the mediator, and Anxiety as the outcome. The paths from Diarrhea to Body Image (b=−.432, p<.001) and from Body Image to Anxiety (b=−.008, p=.002) were significant. However, the unmediated path (total effect; b=.003, p=.29) and the direct effect (b=−.001, p=.72) of Diarrhea on Anxiety were not significant. The indirect effect of Diarrhea on Anxiety via Body Image was significant (BMED=0.003, 95% BCa CI [0.001 – 0.007]), suggesting inconsistent mediation [35]. The mediating role of Body Image in this model should be interpreted with caution as the direct and total effects of Diarrhea on Anxiety were small and not statistically different from zero.

The final mediation model tested the indirect effect of GI Symptoms on Anxiety through Body Image. The paths from GI Symptoms to Body Image (b=−.754, p<.001) and from GI Symptoms to Anxiety (b=.013, p<.001) were significant. However, the path from Body Image to Anxiety (b=−.004, p=.15) was not significant. When Body Image was included in the model, the indirect effect of GI Symptoms on Anxiety via Body Image was not significantly different from zero (BMED=0.003, 95% BCa CI [-0.001 – 0.008]) and the direct effect of GI Symptoms to Anxiety remained significant (b=.010, p=.007). Findings support a direct effect of GI Symptoms on Anxiety, but mediation between GI Symptoms and Anxiety via Body Image was not supported.

Discussion

Among women who averaged four years post-treatment for rectal and anal cancer, greater severity of diarrhea and GI symptoms directly related to poorer body image and greater depressive and anxiety symptoms. Poorer body image emerged as a significant mediator of the negative effects of diarrhea and GI dysfunction on depressive symptoms. Contrary to expectations, body image did not mediate the effect of diarrhea and GI symptoms on anxiety.

Persistent, unwanted changes in body functioning as a result of cancer treatments can profoundly affect the ways in which survivors view themselves and interact with the world. Bowel dysfunction, for example, is associated with social stigma and patients’ difficulty managing irregularity and unpredictability and fear of incontinence often leads to disruptions in social functioning.[23] Poorly managed bowel and GI symptoms lead to reduced quality of life and lowered self-confidence.[36, 12] Women may feel embarrassed or self-conscious, particularly in the context of dating and romantic relationships, or during sexual activity.[37] Forty-seven percent of women in our sample reported feeling less feminine as a result of their disease and treatment and 40% reported feeling less attractive. The development of body image problems may exacerbate these difficulties and lead to increased risk of depression. Importantly, body image represents an inherently subjective construct and may persist even if side effects subside.[2, 19, 21]

Associations were weaker with the anxiety symptoms subscale, and mediation was not fully supported. In bivariate analyses, GI symptoms, but not diarrhea, related to anxiety. In non-cancer populations, both diarrhea and GI symptoms are associated with increased anxiety [38], and it is unknown why diarrhea was unrelated to anxiety in our sample. Items used to measure anxiety in these analyses did not include GI symptoms, but did measure physical sensations of feeling “tense or keyed up” and “nervousness or shakiness inside.” In the test of mediation, this overlap may have precluded relations with body image to emerge.

This study provides some insight into the ways in which body image problems may exacerbate other difficulties associated with treatment effects. Findings are partially consistent with the literature [3]. After colorectal cancer treatment, Bullen et al. [26] demonstrated that in the three month post-operative time period, poor body image predicted worsening depression and anxiety over time. Sharpe et al. [24] reported cross-sectional relations between body image and depression and anxiety in colorectal patients immediately following surgery, though longitudinal relations were only significant for anxiety, not depression. Both studies included a greater proportion of stoma patients than we had in our sample, which was found to increase the risk of deteriorating body image over time [24, 26].

Further investigation of differential predictors of depressive vs. anxiety symptoms in long-term rectal and anal cancer survivorship is warranted. Findings suggest depressive symptoms may directly improve as body image concerns are addressed, even in the presence of diarrhea and GI symptoms and controlling for the effects of age and stoma status. Given that body image and anxiety symptoms were related in bivariate analyses and based on the literature, further investigation into the potential utility of addressing body image problems to alleviate anxiety may be insightful. Alternatively, anxiety symptoms may have other, more significant predictors and there may be better targets of intervention to address this aspect of psychological distress.

While predictive relations cannot be assumed, longitudinal studies suggest that targeting body image problems lead to improvements in more general indicators of psychosocial well being in colorectal [24, 26], breast [43, 44], and head and neck cancer survivorship [45]. Hopwood and Maguire [18] argue that for cancer survivors who experience change in body function, disturbances in body image are one of the primary mechanisms that explain observed increases in psychological morbidity. This is supported by theory that delineates body image as a precursor to more global psychosocial difficulties among cancer survivors. For example, cognitive behavioral models identify “body image schemas,” which when threatened by perceived or actual changes in body functioning or appearance, influence cognitive processing, emotional experiences, and compensatory behaviors [17].

Based on this literature, a baseline, pre-treatment assessment of patients’ body perceptions and expectations for post-treatment recovery could help identity patients at risk for post-treatment difficulties and streamline the delivery of supportive services. Likewise, periodic assessment of body image concerns in survivorship care may help identify the development of body image problems. Psychosocial interventions should be offered to women who have difficulty adjusting to and coping with persistent treatment-related side effects.

Prevailing evidence supports the use of time-limited, cognitive behavioral therapy to address issues related to body image after cancer treatment, though other techniques have also shown promise (e.g., educational and physical fitness interventions) [3]. In addition to learning problem solving strategies to manage symptoms, addressing maladaptive body schemas and promoting acceptance of changes in body functioning and/or appearance may be critical. Women may also benefit from learning communication strategies to navigate uncomfortable situations in which bowel and GI symptoms could interfere with social or sexual encounters. Women may harbor cognitive distortions regarding their partners’ (or future partners’) reaction to body changes. Addressing their fears of rejection or embarrassment may be important. Further work is needed to empirically test whether improvements in body image lead to improved psychological distress in this patient population.

The present study has several limitations. Although analyses were based on theoretical models of body image in cancer populations, cross-sectional analyses preclude causal inferences. The relatively small sample size and primary focus of the study prevented the inclusion of additional, potentially important covariates (e.g., premorbid mood disorders, history of psychopathology). We were also unable to consider other potentially important aspects of post-treatment recovery. For example, although sexual satisfaction was controlled for methodologically, post-treatment sexual dysfunction has been shown to directly relate to body image disturbances and the complex interaction of these constructs should be evaluated further [27]. The sample was made up of women who agreed to participate in a sexual health intervention study and reported moderate to low sexual satisfaction. Participants’ sexual dissatisfaction, as well as their willingness to participate in a sexual intervention, may indicate important distinctions from other survivors. Although this may represent an important subgroup that may be vulnerable to body image difficulties, our findings may not generalize to broader populations of rectal and anal cancer survivors.

Conclusions

A wealth of literature has explored factors associated with heightened psychological distress and poor quality of life in cancer survivorship. Many of these are immutable (e.g., age, disease stage, cancer treatment). In contrast, body image may be a more modifiable risk factor that can be targeted by psychosocial interventions. These preliminary findings suggest that body image concerns may be associated with increased psychological distress resulting from persistent side effects following rectal and anal cancer treatment. Further work is needed to understand how trajectories of body image interact with the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms over time. Interventions to improve adjustment and quality of life should address treatment side effects, but also target body image concerns to alleviate depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Russ Clay, Ph.D. for his guidance with statistical analyses.

Funding: Support for this research was provided by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA129195-01, DuHamel, PI; T32 CA009461, Jamie Ostroff, PI).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Bentzen AG, Balteskard L, Wanderas EH, Frykholm G, Wilsgaard T, Dahl O, Guren MG. Impaired health-related quality of life after chemoradiotherapy for anal cancer: late effects in a national cohort of 128 survivors. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:736–744. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.770599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thong MS, Mols F, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, Roukema JA, Martijn H, van de Poll-Franse LV. Impact of preoperative radiotherapy on general and disease-specific health status of rectal cancer survivors: a population-based study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fingeret MC, Teo I, Epner DE. Managing body image difficulties of adult cancer patients: lessons from available research. Cancer. 2014;120:633–641. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.How P, Stelzner S, Branagan G, Bundy K, Chandrakumaran K, Heald RJ, Moran B. Comparative quality of life in patients following abdominoperineal excision and low anterior resection for low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:400–406. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182444fd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peeters KC, van de Velde CJ, Leer JW, Martijn H, Junggeburt JM, Kranenbarg EK, Steup WH, et al. Late side effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: increased bowel dysfunction in irradiated patients--a Dutch colorectal cancer group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theodoropoulos GE, Papanikolaou IG, Karantanos T, Zografos G. Post-colectomy assessment of gastrointestinal function: a prospective study on colorectal cancer patients. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:525–536. doi: 10.1007/s10151-013-1008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Aaronson NK. The construction and testing of the eortc colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38). European organization for research and treatment of cancer study group on quality of life. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:238–247. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsey SD, Berry K, Moinpour C, Giedzinska A, Andersen MR. Quality of life in long term survivors of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1228–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider EC, Malin JL, Kahn KL, Ko CY, Adams J, Epstein AM. Surviving colorectal cancer: patient-reported symptoms 4 years after diagnosis. Cancer. 2007;110:2075–2082. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles G, Haigh R, McLean C, Phillips HA, Dunlop MG, Din FV. Long term effect of surgery and radiotherapy for colorectal cancer on defecatory function and quality of life. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen L, Herrmann A, Stegmaier C, Singer S, Brenner H, Arndt V. Health-related quality of life during the 10 years after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3263–3269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Impact of bowel dysfunction on quality of life after sphincter-preserving resection for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1377–1387. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor C, Bradshaw E. Tied to the toilet: lived experiences of altered bowel function (anterior resection syndrome) after temporary stoma reversal. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40:415–421. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e318296b5a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fakhrian K, Sauer T, Dinkel A, Klemm S, Schuster T, Molls M, Geinitz H. Chronic adverse events and quality of life after radiochemotherapy in anal cancer patients: a single institution experience and review of the literature. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189:486–494. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray NM, Hall SJ, Browne S, Johnston M, Lee AJ, Macleod U, Mitchell ED, et al. Predictors of anxiety and depression in people with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(2):307–314. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1963-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Hiratsuka K, Yasuda N, Shibusawa M, Kusano M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s10147-005-0524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White CA. Body image dimensions and cancer: a heuristic cognitive behavioural model. Psychooncology. 2000;9:183–192. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<183::aid-pon446>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopwood P, Maguire GP. Body image problems in cancer patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;(Suppl):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allal AS, Gervaz P, Gertsch P, Bernier J, Roth AD, Morel P, Bieri S. Assessment of quality of life in patients with rectal cancer treated by preoperative radiotherapy: a longitudinal prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1129–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendren SK, O'Connor BI, Liu M, Asano T, Cohen Z, Swallow CJ, Macrae HM, et al. Prevalence of male and female sexual dysfunction is high following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:212–223. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171299.43954.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pucciarelli S, Del Bianco P, Efficace F, Serpentini S, Capirci C, De Paoli A, Amato A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: a multicenter prospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2011;253:71–77. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fcb856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corte H, Lefevre JH, Dehnis N, Shields C, Chaouat M, Tiret E, Parc Y. Female sexual function after abdominoperineal resection for squamous cell carcinoma of the anus and the specific influence of colpectomy and vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:774–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desnoo L, Faithfull S. A qualitative study of anterior resection syndrome: the experiences of cancer survivors who have undergone resection surgery. Eur J Cancer Care. 2006;15:244–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharpe L, Patel D, Clarke S. The relationship between body image disturbance and distress in colorectal cancer patients with and without stomas. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sideris L, Zenasni F, Vernerey D, Dauchy S, Lasser P, Pignon JP, Elias D, et al. Quality of life of patients operated on for low rectal cancer: Impact of the type of surgery and patients' characteristics. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2180–2191. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullen TL, Sharpe L, Lawsin C, Patel DC, Clarke S, Bokey L. Body image as a predictor of psychopathology in surgical patients with colorectal disease. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.da Silva GM, Hull T, Roberts PL, Ruiz DE, Wexner SD, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, et al. The effect of colorectal surgery in female sexual function, body image, self-esteem and general health: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2008;248:266–272. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181820cf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philip EJ, Nelson C, Temple L, Carter J, Schover L, Jennings S, Jandorf L, et al. Psychological correlates of sexual dysfunction in female rectal and anal cancer survivors: analysis of baseline intervention data. J Sex Med. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jsm.12152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derogatis LR. 3rd. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson; 1992. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes AF. Beyond baron and kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76:408–420. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayes AF. Process: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [white paper] 2012 http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- 35.MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1:173. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gami B, Harrington K, Blake P, Dearnaley D, Tait D, Davies J, Norman AR, et al. How patients manage gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:987–994. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krychman M, Millheiser LS. Sexual health issues in women with cancer. J Sex Med 10 Suppl. 2013;1:5–15. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Are anxiety and depression related to gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:294–298. doi: 10.1080/003655202317284192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D. C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jerndal P, Ringström G, Agerforz P, Karpefors M, Akkermans LM, Bayati A, Simrén M. Gastrointestinal-specific anxiety: an important factor for severity of GI symptoms and quality of life in IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:646–e179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keightley PC, Koloski NA, Talley NJ. Pathways in gut-brain communication: evidence for distinct gut-to-brain and brain-to-gut syndromes. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:207–214. doi: 10.1177/0004867415569801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Figueiredo MI, Cullen J, Hwang YT, Rowland JH, Mandelblatt JS. Breast cancer treatment in older women: does getting what you want improve your long-term body image and mental health? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4002–4009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carver CS, Pozo-Kaderman C, Price AA, Noriega V, Harris SD, Derhagopian RP, Robinson DS, et al. Concern about aspects of body image and adjustment to early stage breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:168–174. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhoten BA, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: A review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White CA, Unwin JC. Post-operative adjustment to surgery resulting in the formation of a stoma: the importance of stoma-related cognitions. Br J Health Psychol. 1998;3:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Gremore TM, Wiesenthal N, Aldridge W, Fredman SJ, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:276–283. doi: 10.1002/pon.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]